Abstract

Background

Ventricular Assist Devices (VADs) have come into increasing use in recent years for children. One year survival rates are now above 80% in multiple reports. This report describes adverse events experienced by children with durable ventricular assist devices, using a national-level registry (Pedimacs, a component of Intermacs)

Methods

Pedimacs is a national registry that contains clinical data on patients who are less than 19 years of age at the time of implantation with a VAD. Data collection concludes at the time of VAD explantation. All FDA-approved devices are included. Pedimacs was launched on September 1, 2012 and this report includes all data from launch until August 2014. Adverse events were coded with a uniform, pre-specified set of definitions.

Results

This report comprises data from 200 patients, with median age of 11 years (range 11 days-18 years), and total follow-up of 783 patient-months. The diagnoses were cardiomyopathy (n=146, 73%), myocarditis (17, 9%), congenital heart disease (35, 18%), and other (2, 1%). Pulsatile flow devices were used in 91 patients (45%), and continuous flow devices in 109 (55%). Actuarial survival was 86% at 6 months. There were 418 adverse events reported. The most frequent events were device malfunction (n=79), infection (78), neurological dysfunction (52), and bleeding (68). Together, these accounted for 277 events, 66% of the total. Although 38% of patients had no reported adverse event, 16% of patients had 5 or more adverse events. Adverse events occurred at all times following implantation but were most likely to occur in the first 30 days. For continuous flow devices, there were broad similarities in adverse event rates between this cohort, and historical rates from the Intermacs population.

Conclusions

In this cohort, the overall rate of early adverse events (within 90 days of implantation) was 86.3 events per 100 patient months, and of late adverse events, 20.4 events per 100 patient months. The most common adverse events in recipients of pulsatile VADs were device malfunction, neurological dysfunction, bleeding and infection. For continuous flow VADs, the most common adverse events were infection, bleeding, cardiac arrhythmia, neurological dysfunction and respiratory failure. Compared to an adult Intermacs cohort, the overall rate and distribution of adverse events appears similar.

Introduction

In the past decade, the use of durable ventricular assist devices (VADs) in children has increased dramatically.1-3 Initially, this primarily consisted of the Berlin Heart EXCOR, a pulsatile, paracorporeal VAD that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for pediatric use in December 2011.4 More recently, continuous flow pumps such as the Thoratec© Heartmate II, and Heartware© HVAD, which were developed and approved for use in adults, have been used in children as both bridge to heart transplant, and on occasion, as destination therapy.5-9

Reports of VAD outcomes in children have demonstrated overall survival rates ranging from 75% to 92%.3, 4, 10 However, early reports were notable for a high rate of neurological adverse events in pulsatile flow devices.4, 11-13 Overall adverse event rates and types have not been described in detail at the national level. The objective of this manuscript is to provide the first contemporary, national-level description of the adverse events associated with the full spectrum of pediatric VAD use in the United States.

Methods

Intermacs (The Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support), is a US national registry of patients supported by FDA approved ventricular assist devices.14 Intermacs, which is supported by the National Institutes of Health, now contains data on more than 10,000 patients.15 Pedimacs, the pediatric component of Intermacs, began enrolling pediatric patients supported with VADs on September 1, 2012.

Pedimacs contains prospectively entered data on patients who are less than 19 years of age at the time of VAD implantation, with data collection continuing through the period of implantation and VAD support, concluding with VAD explantation. Similar to Intermacs, Pedimacs contains data on all Food and Drug Administration approved devices. For Pedimacs but not Intermacs, this includes devices placed for temporary support of heart failure. However, this analysis is confined to those devices implanted for durable support. Data were analyzed for patients enrolled between September 19th, 2012 and June 30th, 2015.

Adverse events in Pedimacs are categorized using a pre-specified dictionary of potential complications that is provided to each participating site. The definitions were derived by expert consensus, working in large part from the definitions already employed in Intermacs, and altering them as necessary to be appropriate for pediatric patients. Pedimacs collects the following adverse events: Arterial Non-CNS Thromboembolism, Bleeding, Cardiac Arrhythmia, Device Malfunction, Hepatic Dysfunction, Infection, Neurological Dysfunction, Other SAE, Pericardial Drainage, Psychiatric Episode, Renal Dysfunction, Respiratory Failure, Venous Thromboembolism, and Wound Dehiscence. A brief definition of selected major adverse events is shown in Table 1. A complete description of all adverse events is provided in the appendix.

Table 1. Major Adverse Events (with brief summary description).

| Adverse Event | Brief description |

|---|---|

| Device Malfunction | The device fails to perform as intended, can be major or minor |

| Major Bleeding Episode | Bleeding episode requiring transfusion, hospitalization, or surgery; or resulting in death |

| Major Infection | Clinical infection treated with an anti-microbial agent |

| Neurological Dysfuction | Temporary or permanent neurological dysfunction or structural injury |

Statistical analysis

Descriptive characteristics were determined for patients receiving pulsatile or continuous flow durable devices. For continuous variables, mean and standard deviation were compared using a two sample t-test. For categorical variables, the count and percentage were compared using a chi-squared test.

The time to the first device malfunction, infection, major bleeding, neurological dysfunction, or the combination of these events were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier estimate. Follow-up for each patient started at the implantation of the patient's first durable MCS device, continued if the device was exchanged, and was censored at death, transplant, or left ventricular recovery.

The number of events of each type was determined for the Pedimacs cohort receiving durable MCS and stratified by continuous or pulsatile flow support. Similar to the methods used in Intermacs, event rates were calculated per 100 pt-months for an early period (within 3 months of implant) and a late period (more than 3 months post implant). For pulsatile devices the early and late event rates are presented. The Pedimacs pulsatile flow group consisted of 91 patients contributing 69.2 patients-months of early follow-up and 30.8 patient-months of late follow-up. For continuous flow devices, the early and late adverse event rates were compared to a contemporaneous enrolled group of Intermacs patients receiving continuous flow devices. The Pedimacs continuous flow group consisted of 109 patients contributing 65.1 patients-months of early follow-up and 34.9 patient-months of late follow-up. The Intermacs continuous flow group consisted of 3,894 patients contributing 977.0 pt-months of early follow-up and 2,917.0 pt-months late follow-up. Statistical significance was considered when p < 0.05.

Results

Patient Population

A total of 200 pediatric patients with durable VAD implantations during the study period comprise this report. The median age of patients was 11 years (range 13d – 18 yr), with 78 females (39%). The etiology of heart disease was cardiomyopathy in 146 (73%) patients, myocarditis in 17 (9%), congenital heart disease in 35 (18%) and other in 2 (1%) patient. Of these patients, 91 (45%) received pulsatile flow devices and 109 (55%) received continuous flow devices. The overall survival on device at 6 months was 81%, including patients who were successfully explanted, those on continuing support and those who successfully underwent transplantation. The total available follow-up was 783 patient-months. For those patients who achieved heart transplantation, the average time from implantation of the first durable device, until the time of transplantation, was 3.8 +/- 3.3 months for those with pulsatile flow devices (n=61), and 3.4 +/- 3.8 months for those with continuous flow devices (n=69).

Table 2 provides a detailed description of the patients' baseline characteristics. Comparing the pulsatile flow and continuous flow populations, the pulsatile flow recipients were significantly younger (4.6 +/- 5.9 years vs 14.4 +/- 3.7, p<0.0001), smaller (BSA 0.7 +/- 0.5 vs 1.7 +/- 0.4, p<0.0001), more likely to have congenital heart disease (26% vs 11.0%, p = 0.0083), and more likely to have undergone prior cardiac surgery (55% vs 24%, p<0.0001). Patients with congenital heart disease most commonly had undergone prior congenital surgical corrections, while those with cardiomyopathy and/or myocarditis, had histories of prior circulatory support such as ECMO or LVAD.

Table 2. Baseline Characteristics of Study Population.

| Pulsatile flow (n=91) | Continuous flow (n=109) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 4.6 +/- 5.0 | 14.4 +/- 3.7 | <.0001 |

| Female | 42 (46.2) | 36 (33.0) | 0.0581 |

| Cardiac diagnosis | |||

| Cardiomyopathy | 56 (61.5) | 90 (82.6) | |

| Myocarditis | 10 (11.0) | 7 (6.4) | |

| Congenital Heart disease | 24 (26.4) | 11 (10.1) | |

| Other | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Race | 0.6849 | ||

| Caucasian | 56 (61.5) | 64 (58.7) | |

| African-American | 35 (38.5) | 45 (41.3) | |

| BSA m2 | 0.7 +/- 0.5 | 1.7 +/- 0.4 | <.0001 |

| Prior Cardiac Surgery | 50 (54.9) | 26 (23.9) | <.0001 |

| Prior ECMO | 22 (24.2) | 8 (7.3) | 0.0009 |

| Intermacs Level | 0.0139 | ||

| I (critical cardiogenic shock) | 32 (36.8) | 20 (19.0) | |

| II (progressive decline on inotropes) | 43 (49.4) | 64 (61.0) | |

| III (stable, but inotrope dependent) | 7 (8.0) | 18 (17.1) | |

| IV (resting symptoms) | 5 (5.7) | 3 (2.9) | |

| Pre-Implant Device Strategy | 0.0068 | ||

| Bridge to Transplant - Listed | 69 (75.8) | 59 (54.1) | |

| Bridge to Candidacy | 19 (20.9) | 44 (40.4) | |

| Destination Therapy | 2 (2.2) | 6 (5.5) | |

| Bridge to Recovery | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Implant Device Type | 0.0068 | ||

| LVAD | 59 (64.8) | 102 (93.6) | |

| RVAD | 3 (3.3) | 1 (0.9) | |

| BiVAD | 23 (25.3) | 6 (5.5) | |

| TAH | 6 (6.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Selected Laboratory Values | |||

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 138.2 +/- 5.8 | 136.3 +/- 6.3 | 0.0254 |

| Blood Urea Nitrogen (mg/dL) | 30.2 +/- 22.4 | 24.5 +/- 15.0 | 0.032 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.6 +/- 0.5 | 1.0 +/- 0.5 | <.0001 |

| Brain Natriuretic Peptide (pg/mL) | 2488.6 +/- 1890.6 | 1641.3 +/- 1460.3 | 0.0156 |

| Pro Brain Natriuretic Peptide (pg/mL) | 17721 +/- 14991 | 8891.7 +/- 9157.8 | 0.0136 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.5 +/- 0.8 | 3.5 +/- 0.5 | 0.4292 |

| NR | 1.4 +/- 0.5 | 1.5 +/- 0.6 | 0.8349 |

At the time of implantation, 27% of patients were Intermacs level I, 55% were identified as Intermacs level II (progressive decline on inotropic support), and 17% were at level III or IV. The overwhelming majority of implantations (128, 64%) were performed as bridge to transplant, with (8, 4%) intended as destination support devices. Device type was LVAD in 161 (80%) patients, RVAD in 4 (2%), and BiVAD in 29 (15%). TAH was used in 6 patients (3%). There was no difference in Intermacs level at implantation between the pulsatile and continuous flow devices, but patients implanted with continuous flow devices were more likely to receive LVAD as device type and were more likely to have bridge to candidacy as device strategy, rather than to be listed already for transplantation.

Adverse Events

There were a total of 28 deaths reported in the study cohort. The primary cause of death was circulatory failure in 7 patients, multi-system organ failure in 11, neurological dysfunction in 4, respiratory failure in 1 and withdrawal of support in 1 patient.

A total of 418 adverse events were recorded for the entire cohort, yielding an overall event rate of 53.4 adverse events per 100 patient months. Re-hospitalization in itself is not a defined adverse event, although most adverse events were also associated with re-hospitalization. Approximately 70% of patients with pulsatile flow devices experienced at least one adverse event (64/91 patients), similar to the proportion of patients supported with continuous flow devices who experienced at least one adverse event (55%, 60/109). The most frequent adverse events were: infection (78), device malfunction (79), major bleeding (68), and neurological dysfunction (52). Together, these 4 adverse event categories were responsible for 277 individual events, 66% of the total. The detailed account of adverse event total is provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Adverse Event Incidence.

| Number of Events | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Event Type | Pulsatile Flow VAD | Continuous Flow VAD | Total |

| Arterial Non-CNS Thromboembolism | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Bleeding | 31 | 37 | 68 |

| Cardiac Arrhythmia | 9 | 17 | 26 |

| Device Malfunction | 63 | 16 | 79 |

| Hepatic Dysfunction | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Infection | 38 | 40 | 78 |

| Pump related, including driveline | (8) | (6) | (14) |

| Bloodstream/Sepsis | (13) | (10) | (23) |

| Pulmonary | (7) | (9) | (16) |

| Other | (10) | (15) | (25) |

| Neurological Dysfunction | 41 | 11 | 52 |

| Ischemic Stroke | (10) | (1) | (11) |

| Hemorrhagic Stroke | (8) | (1) | (9) |

| Other | (23) | (9) | (32) |

| Other SAE | 22 | 18 | 40 |

| Pericardial Drainage | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| Psychiatric Episode | 1 | 9 | 10 |

| Renal Dysfunction | 8 | 7 | 15 |

| Respiratory Failure | 12 | 14 | 26 |

| Venous Thromboembolism | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Wound Dehiscence | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 232 | 186 | 418 |

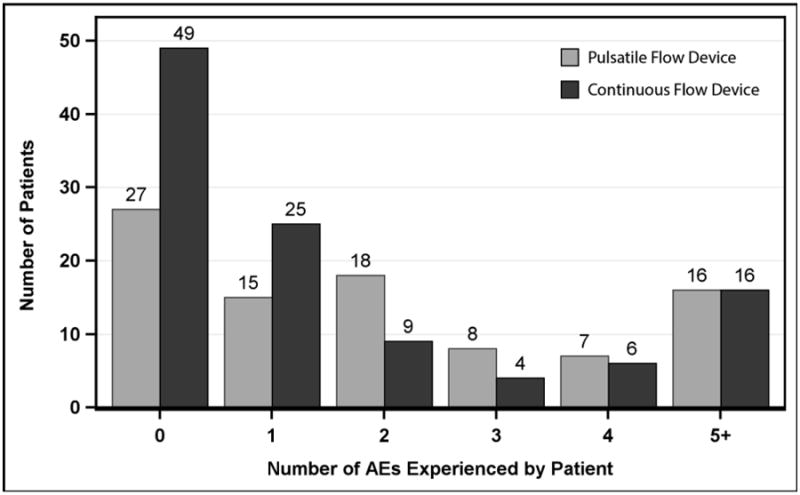

Figure 1 shows the number of adverse events per patient. Thus, 76 patients experienced no adverse events, while 57 patients experienced 3 or more events during the VAD support interval. Additionally, 32 patients experienced 5 or more adverse events, and this group accounted for 236 total events (56% of the total events). The patients who experienced no adverse events had a median support time of 1.4 months.

Figure 1. Number of Adverse Events per Patient.

Pedimacs patients receiving durable implants, Sept 2012 to Aug 2015 (patients=200)

Late versus Early Adverse Events

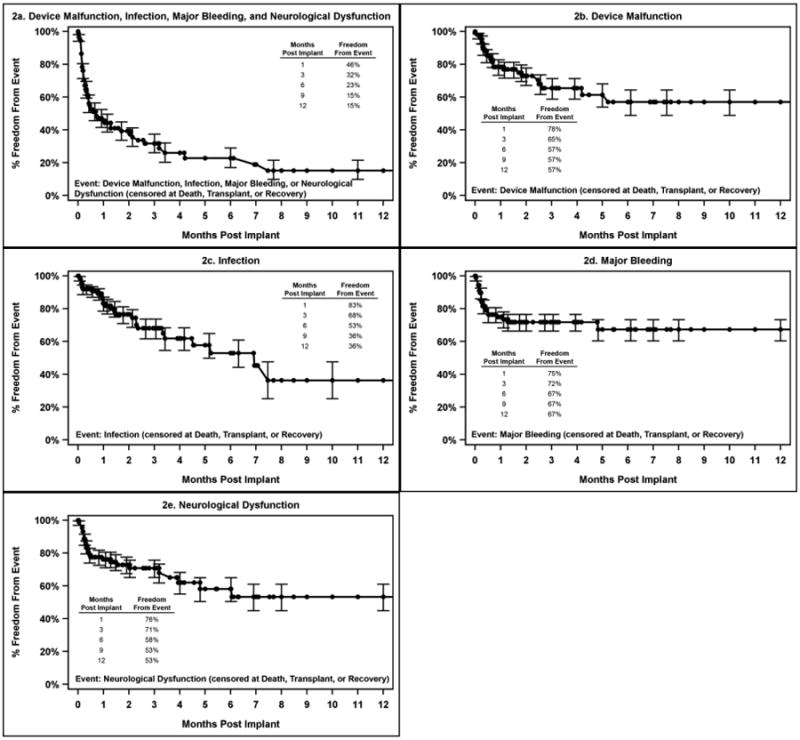

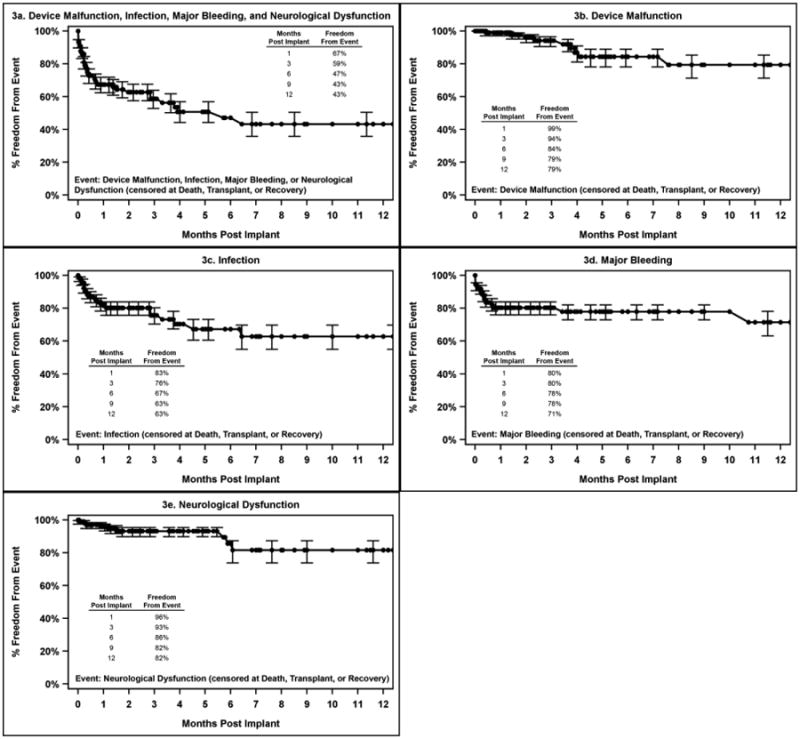

Time to first adverse event is depicted in Figure 2 and 3 for pulsatile and continuous flow devices, respectively. In each figure, analysis is performed separately for device malfunction, infection, major bleeding and neurological dysfunction. Panel a shows the time to any of these major events combined. As can be seen by this analysis, for pulsatile devices, bleeding events and neurological dysfunction events tended to occur early, while infection and device malfunction were more evenly distributed over time. For continuous flow devices, bleeding was again found to occur early, while the other events were more widely distributed temporally. Overall, by 90 days, the freedom from any of these major adverse events was approximately 32% for pulsatile devices and 59% for continuous flow devices.

Figure 2. Time to First Adverse Event for Patients on Pulsatile Flow Devices.

Pedimacs patients receiving durable implants Sept 2012 to Aug 2015 (patients=91)

Figure 3. Time to First Adverse Event for Patients on Continuous Flow Devices.

Pedimacs patients receiving durable implants Sept 2012 to Aug 2015 (patients=109)

Early adverse events are defined by Intermacs as those occurring during the first 90 days of support, while late events are any that occur after 90 days. The early adverse event rate for the entire Pedimacs cohort was 109 events per 100 pt-months, while the late event rate was 34.4 events per 100 pt-months. This difference was statistically significant (p<0.0001)

The adverse event rate for each event type is shown in Table 4 for pulsatile devices and Table 5 for continuous flow devices, with separation by early vs late events. Due to the important differences in patient populations between pulsatile and continuous flow devices, these data are not presented as a comparison of device types. Contemporaneous Intermacs data (limited to patients with implant strategy of bridge to transplant listed, or bridge to candidacy) are shown as a comparator for AE rates for continuous flow devices.

Table 4. Adverse Event Rates for Pulsatile Flow Devices.

| Event Rate per 100 pt-months | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event Type | Timing | Event Count | AE Rate per 100 pt-months |

| Arterial Non-CNS embolism | Early | ||

| Late | |||

| Bleeding | Early | 28 | 16.1 |

| Late | 3 | 2.4 | |

| Cardiac Arrhythmia | Early | 8 | 4.6 |

| Late | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Device Malfunction | Early | 51 | 19.4 |

| Late | 12 | 9.6 | |

| Hepatic Dysfunction | Early | 2 | 1.2 |

| Late | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Infection | Early | 26 | 15 |

| Late | 12 | 9.6 | |

| Neurological Dysfunction | Early | 34 | 19.6 |

| Late | 7 | 5.6 | |

| Other SAE | Early | 19 | 10.9 |

| Late | 3 | 2.4 | |

| Pericardial Drainage | Early | 4 | 2.3 |

| Late | |||

| Psychiatric Episode | Early | 1 | 0.6 |

| Late | |||

| Renal Dysfunction | Early | 6 | 3.5 |

| Late | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Respiratory Failure | Early | 10 | 5.8 |

| Late | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Venous Thromboembolism | Early | ||

| Late | |||

| Wound Dehiscence | Early | ||

| Late | |||

Table 5. Adverse Events Rates for Continuous Flow Devices.

| Pedimacs Adverse Events2 | INTERMACS Adverse events3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event Typ | Timing1 | Event Count | AE Rate per 100 pt-months | Event Count | AE Rate per 100 pt-months | RateRatio |

| Arterial Non-CNS embolism | Early | 2 | 0.9 | 45 | 0.4 | 2.1 |

| Late | 9 | 0 | ||||

| Bleeding | Early | 31 | 14.2 | 1352 | 12.9 | 1.1 |

| Late | 6 | 2.2 | 884 | 2.7 | 0.8 | |

| Cardiac Arrhythmia | Early | 15 | 6.9 | 1031 | 9.8 | 0.7 |

| Late | 2 | 0.7 | 370 | 1.1 | 0.7 | |

| Device Malfunction | Early | 6 | 2.8 | 261 | 2.5 | 1.1 |

| Late | 10 | 3.7 | 390 | 1.2 | 3.1* | |

| Hepatic Dysfunction | Early | 4 | 1.8 | 110 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Late | 49 | 0.2 | ||||

| Infection | Early | 28 | 12.9 | 1319 | 12.5 | 1 |

| Late | 12 | 4.5 | 1267 | 3.9 | 1.2 | |

| Myocardial Infarction | Early | 4 | 0 | |||

| Late | 9 | 0 | ||||

| Neurological Dysfunction | Early | 9 | 4.1 | 433 | 4.1 | 1 |

| Late | 2 | 0.7 | 425 | 1.3 | 0.6 | |

| Other SAE | Early | 15 | 6.9 | 1322 | 12.6 | 0.5 |

| Late | 3 | 1.1 | 612 | 1.9 | 0.6 | |

| Pericardial Drainage | Early | 9 | 4.1 | 148 | 1.4 | 2.9* |

| Late | 7 | 0 | ||||

| Psychiatric Episode | Early | 9 | 4.1 | 192 | 1.8 | 2.3 |

| Late | 81 | 0.2 | ||||

| Renal Dysfunction | Early | 6 | 2.8 | 353 | 3.4 | 0.8 |

| Late | 1 | 0.4 | 115 | 0.4 | 1.1 | |

| Respiratory Failure | Early | 14 | 6.4 | 633 | 6 | 1.1 |

| Late | 173 | 0.5 | ||||

| Venous Thromboembolism | Early | 1 | 0.5 | 114 | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| Late | 12 | 0 | ||||

| Wound Dehiscence | Early | 38 | 0.4 | |||

| Late | 1 | 0.4 | 13 | 0 | 9.4 | |

Timing: early events occurred within 3 months of initial implant, Late events occurred more than 3 months after initial implant

Pedimacs Continuous Flow Group: 109 patients, 217.9 pt-months early follow-up, 266.8 pt-months late follow-up

Intermacs Continuous Flow Group: 3,894 patients, 10,520.1 pt-months early follow-up, 32,581.0 pt-months late follow-up

p < 0.05k

Consistent with the actual event counts, the AE's with the highest early event rate for pulsatile devices were device malfunction (29.4 events per 100 pt-months), followed by neurological dysfunction (19.6), major bleeding (16.1), and infection (15). For late events, other serious adverse event was the AE with the greatest event rate 10.9 events per 100 pt-months, with device malfunction following at 9.6 events per 100 pt-months,. Other late events were observed much less commonly for pulsatile devices.

For continuous flow devices, the AE with the highest early event rate was bleeding (14.2 events per 100 pt-months), followed by infection (12.6), cardiac arrhythmia and other serious adverse event (6.9), respiratory failure (6.4), and lastly Neurological Dysfunction, Pericardial Drainage, and Psychiatric Episode (4.1). The most common late adverse events among continuous flow devices included infection (4.5 events per 100 pt-months), and device malfunction (3.8).

Adult versus Pediatric Continuous Flow Devices

Among early adverse events, pericardial drainage was reported more frequently in Pedimacs than in Intermacs (rate ratio 2.9, p <0.001). Device malfunction was reported as a late AE more commonly in Pedimacs than in Intermacs (rate ratio 3.1, p <0.05). However, on the whole, the data are more notable for the similarities between the two populations rather than for any consistent pattern of differences.

Rehospitalization

In these analyses, hospitalizations have not been counted as adverse events, but the reason for hospitalization was coded as an adverse event (including the code of “other”). However, given the importance of re-hospitalization, we analyzed re-hospitalization separately. Since hospital discharge was quite rare for pulsatile devices (and occurred in the setting of Total Artificial Heart), this analysis is confined to patients supported with continuous flow devices. In this cohort, there were 48 patients who were discharged from the hospital on at least one occasion. There were a total of 74 re-hospitalizations among this cohort, of which 15 were performed for the purpose of performing heart transplantation and 2 were performed for device explantation. These cases are excluded from further analysis. The remaining 57 re-hospitalizations encompass a broad range of underlying reasons, including anticoagulation management (10), device malfunction or alarm (8), other planned procedure (3), cardiac arrhythmia (2), and other (33). Given the broad distribution of causes for re-hospitalization, no further analysis of this was performed.

Discussion

This is the first national-level account of the burden of adverse events associated with use of ventricular assist devices in children. As survival rates for these devices are quite good, and as previous smaller reports have indicated significant morbidity from use of VADs, this report offers timely event-specific information that allows for a more complete understanding of the risks associated with this important therapy.2-4, 6, 10, 11, 16, 17 There are several findings that we wish to highlight from this initial report.

It is perhaps overly simplistic to propose that there is an “acceptable” overall adverse event rate. Firstly, these devices are for the most part still being used in circumstances where the alternative to device support is death. Secondly, different adverse events have profoundly different impact on patients. From the patient perspective, a stroke can hardly be compared to a bleeding episode that is treated with blood transfusion and observation. Therefore, summary data concerning adverse event rates should be interpreted with caution. However, the overall rates do provide a general sense of the inherent complexity and instability of a treatment, as it is provided in a specific context. In this regard, the adverse event rate of 53.4 events per 100 patient months for the entire cohort can be regarded as a useful benchmark for future progress in pediatric VAD support. Interestingly, this rate compares favorably with contemporaneous data from VAD use in adults, despite the considerable differences in patient volume between pediatric and adult programs. It should be noted, however, that comparing the Pedimacs results with continuous flow devices to the contemporaneous adult experience reported in Intermacs was somewhat problematic due to the small size of the Pedimacs cohort, which resulted in small absolute numbers of events, particularly for late events. Events that occurred uncommonly result in unstable rate ratios in which the p-values can be misleading.

In adults, continuous flow VADs are used far more frequently than pulsatile flow devices, which stands in sharp contrast to this report, where the distribution between these device types in children was roughly even. This difference is attributable primarily to the fact that the only VAD in use today with FDA approval for use in children is the pulsatile EXCOR VAD manufactured by Berlin Heart. Additionally, even with off-label use, there is a lack of continuous flow devices suitable for very small children, with a practical lower weight limit of approximately 17 kg for currently available continuous flow VADs.6 With the upcoming PUMPKin trial and the anticipated development of smaller adult continuous flow VADs, this ratio may change in the future.

In the meantime, our data demonstrate very different patient characteristics between those patients treated with continuous flow VADs and those treated with pulsatile VADs. The recipients of continuous flow VADs tend to be larger and older while the recipients of pulsatile flow devices are more likely to have congenital heart disease. For these reasons, a comparison of adverse events between continuous flow and pulsatile flow VADs does not provide much insight into differences between the devices per se. This report has intentionally de-emphasized this comparison, due to the inherent difficulty in understanding the basis for differences between these groups.

For patients implanted with pulsatile devices, the most common early complications were device malfunction, neurological dysfunction, bleeding and infection. Overall, adverse events were more commonly encountered in the early period, with a significant reduction in adverse event rate in the later period (beyond 90 days). For pulsatile devices, the defined adverse event of device malfunction includes exchange of the pump component of the Berlin Heart EXCOR, and it should be noted that this procedure can be performed at bedside in the ICU, and is in no way comparable in scope to replacement of an intra-corporeal continuous flow VAD.18 The pump component of the EXCOR is commonly replaced due to an increased thrombotic burden within the pump, and replacement does not signify a loss of pump function, or risk thereof.

For continuous flow devices, the most common early complications included infection, major bleeding, cardiac arrhythmia, neurological dysfunction and respiratory failure. Late neurological events were present, but uncommon. Should this finding be upheld in further analyses of larger cohorts, this would have an important bearing on the timing of implantation, as stroke remains a highly feared complication of VAD therapy in children. In contrast to emerging experience with adult patients supported with continuous flow devices, right ventricular failure was not common in this cohort. This may relate to the relatively short interval of VAD support, or may be related to other underlying issues of the disease process in younger patients.

It is interesting that the infection rate appears to be lower with use of pulsatile devices than with continuous flow devices. There are several potential explanations for this observation. It may represent a mismatch of equipment size between the continuous flow devices and the recipient body habitus, which is not present for pulsatile devices that come in a variety of sizes appropriate for pediatric use. Alternatively, this may arise from the fact that pulsatile flow devices require ongoing hospitalization and the level of site care may be more attentive or more skilled in this situation than it is out of the hospital. Finally, this difference may be attributable to the level of activity of the patient population, wherein a more active patient is more likely to sustain a driveline infection.

Additionally, it should be noted that for pulsatile devices, a biventricular support mode was employed in 25.3% of patients (for continuous flow devices, this was 5.5%). While it is possible that the use of biventricular support is associated with higher rates of adverse events, the relatively small number of such patients precludes a formal analysis of that question until the dataset is larger. The high rate of biventricular support likely reflects a learning curve among centers with respect to timing of implantation. It is also noteworthy that in the continuous flow group, 17% of the implantations were performed at Intermacs Level III, which suggests a substantial move towards less urgent indications for implantation.

Overall, this initial report of adverse events associated with VAD utilization in children provides a starting point for understanding better the balance between risk and benefit in this therapy. As reported here, the overall and specific adverse event rates are acceptable in the context in which VADs are used in children, primarily as a life saving bridge to heart transplantation. As more centers accrue experience with pediatric VAD use, and as devices themselves improve, we anticipate that the adverse event rates can be further reduced. Ongoing enrollment of patients into Pedimacs from a large variety of centers provides an ideal data source to explore these questions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mansfield RT, Lin KY, Zaoutis T, Mott AR, Mohamad Z, Luan X, Kaufman BD, Ravishankar C, Gaynor JW, Shaddy RE, Rossano JW. The Use of Pediatric Ventricular Assist Devices in Children's Hospitals From 2000 to 2010: Morbidity, Mortality, and Hospital Charges. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015 doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blume ED, Naftel DC, Bastardi HJ, Duncan BW, Kirklin JK, Webber SA. Outcomes of children bridged to heart transplantation with ventricular assist devices: a multi-institutional study. Circulation. 2006;113:2313–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.577601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morales DL, Almond CS, Jaquiss RD, Rosenthal DN, Naftel DC, Massicotte MP, Humpl T, Turrentine MW, Tweddell JS, Cohen GA, Kroslowitz R, Devaney EJ, Canter CE, Fynn-Thompson F, Reinhartz O, Imamura M, Ghanayem NS, Buchholz H, Furness S, Mazor R, Gandhi SK, Fraser CD., Jr Bridging children of all sizes to cardiac transplantation: the initial multicenter North American experience with the Berlin Heart EXCOR ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraser CD, Jr, Jaquiss RD, Rosenthal DN, Humpl T, Canter CE, Blackstone EH, Naftel DC, Ichord RN, Bomgaars L, Tweddell JS, Massicotte MP, Turrentine MW, Cohen GA, Devaney EJ, Pearce FB, Carberry KE, Kroslowitz R, Almond CS. Prospective trial of a pediatric ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:532–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padalino MA, Bottio T, Tarzia V, Bortolussi G, Cerutti A, Vida VL, Gerosa G, Stellin G. HeartWare ventricular assist device as bridge to transplant in children and adolescents. Artif Organs. 2014;38:418–22. doi: 10.1111/aor.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miera O, Potapov EV, Redlin M, Stepanenko A, Berger F, Hetzer R, Hubler M. First experiences with the HeartWare ventricular assist system in children. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1256–60. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cabrera AG, Sundareswaran KS, Samayoa AX, Jeewa A, McKenzie ED, Rossano JW, Farrar DJ, Frazier OH, Morales DL. Outcomes of pediatric patients supported by the HeartMate II left ventricular assist device in the United States. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:1107–13. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Connor MJ, Rossano JW. Ventricular assist devices in children. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2014;29:113–21. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinhartz O, Copeland JG, Farrar DJ. Thoratec ventricular assist devices in children with less than 1.3 m2 of body surface area. ASAIO J. 2003;49:727–30. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000093965.33300.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almond CS, Morales DL, Blackstone EH, Turrentine MW, Imamura M, Massicotte MP, Jordan LC, Devaney EJ, Ravishankar C, Kanter KR, Holman W, Kroslowitz R, Tjossem C, Thuita L, Cohen GA, Buchholz H, St Louis JD, Nguyen K, Niebler RA, Walters HL, 3rd, Reemtsen B, Wearden PD, Reinhartz O, Guleserian KJ, Mitchell MB, Bleiweis MS, Canter CE, Humpl T. Berlin Heart EXCOR pediatric ventricular assist device for bridge to heart transplantation in US children. Circulation. 2013;127:1702–11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein ML, Robbins R, Sabati AA, Reinhartz O, Chin C, Liu E, Bernstein D, Roth S, Wright G, Reitz B, Rosenthal D. Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (Intermacs)-defined morbidity and mortality associated with pediatric ventricular assist device support at a single US center: the Stanford experience. Circulation Heart failure. 2010;3:682–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.918672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassidy J, Dominguez T, Haynes S, Burch M, Kirk R, Hoskote A, Smith J, Fenton M, Griselli M, Hsia TY, Ferguson L, Van Doorn C, Hasan A, Karimova A. A longer waiting game: bridging children to heart transplant with the Berlin Heart EXCOR device--the United Kingdom experience. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:1101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polito A, Netto R, Soldati M, Brancaccio G, Grutter G, Amodeo A, Ricci Z, Morelli S, Cogo P. Neurological complications during pulsatile ventricular assistance with the Berlin Heart EXCOR in children: incidence and risk factors. Artif Organs. 2013;37:851–6. doi: 10.1111/aor.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Stevenson LW, Kormos RL, Pagani FD, Miller MA, Ulisney K, Young JB. Intermacs database for durable devices for circulatory support: first annual report. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1065–72. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, Kormos RL, Stevenson LW, Blume ED, Miller MA, Timothy Baldwin J, Young JB. Sixth Intermacs annual report: a 10,000-patient database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:555–64. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hetzer R, Alexi-Meskishvili V, Weng Y, Hubler M, Potapov E, Drews T, Hennig E, Kaufmann F, Stiller B. Mechanical cardiac support in the young with the Berlin Heart EXCOR pulsatile ventricular assist device: 15 years' experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2006:99–108. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeewa A, Manlhiot C, McCrindle BW, Van Arsdell G, Humpl T, Dipchand AI. Outcomes with ventricular assist device versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to pediatric heart transplantation. Artificial organs. 2010;34:1087–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2009.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malaisrie SC, Pelletier MP, Yun JJ, Sharma K, Timek TA, Rosenthal DN, Wright GE, Robbins RC, Reitz BA. Pneumatic paracorporeal ventricular assist device in infants and children: initial Stanford experience. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:173–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.11.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]