Abstract

Western blotting is a commonly used protein assay that combines the selectivity of electrophoretic separation and immunoassay. The technique is limited by long time, manual operation with mediocre reproducibility, and large sample consumption, typically 10–20 μg per assay. Western blots are also usually used to measure only one protein per assay with an additional housekeeping protein for normalization. Measurement of multiple proteins is possible; however, it requires stripping membranes of antibody and then reprobing with a second antibody. Miniaturized alternatives to Western blot based on microfluidic or capillary electrophoresis have been developed that enable higher-throughput, automation, and greater mass sensitivity. In one approach, proteins are separated by electrophoresis on a microchip that is dragged along a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane so that as proteins exit the chip they are captured on the membrane for immunoassay. In this work, we improve this method to allow multiplexed protein detection. Multiple injections made from the same sample can be deposited in separate tracks so that each is probed with a different antibody. To further enhance multiplexing capability, the electrophoresis channel dimensions were optimized for resolution while keeping separation and blotting times to less than 8 min. Using a 15 μm deep × 50 μm wide × 8.6 cm long channel it is possible to achieve baseline resolution of proteins that differ by 5% in molecular weight, e.g. ERK1 (44 kDa) from ERK2 (42 kDa). This resolution allows similar proteins detected by cross-reactive antibodies in a single track. We demonstrate detection of 11 proteins from 9 injections from a single Jurkat cell lysate sample consisting of 400 ng total protein using this procedure. Thus, multiplexed Western blots are possible without cumbersome stripping and reprobing steps.

Introduction

Western blotting1 is a semi-quantitative protein assay that combines sieving electrophoresis and immunoassay. In this technique, proteins are separated by sieving electrophoresis and then transferred and blotted onto a membrane where target proteins are detected by an immunoassay. Western blotting has become a routine tool for biochemistry research because it is inexpensive, provides high specificity, and can be easily optimized. Even though Western blotting is a workhorse method, it has a number of limitations such as long analysis time (~20 h), lack of automation, and sample consumption, typically 10 μg total protein per assay, that is incompatible with small samples.

Several variations on Western blot have been developed to alleviate these limitations2–4. Systems based on capillary and microchip electrophoresis (MCE) have been developed to improve the speed, automation, and mass sensitivity of Western blotting5–12. These systems take advantage of the speed of protein sieving electrophoresis that can be obtained in miniaturized channels13–16. In some cases, sieved proteins are captured by photo-induced cross-linking to the sieving gel or capillary wall, allowing for subsequent in situ immunoprobing12,17,18. Our lab has developed a method where proteins separated by capillary or MCE are blotted onto a membrane as they exit the separation path10,11. In this work, we show that MCE interfaced to membrane can also be used to improve the information content of Western blotting by enabling multiplexed assays.

Traditional Western blotting is usually confined to measuring one protein per assay. To overcome this limitation, reblotting techniques have been developed that allow more than one protein to be detected19. In such procedures, the membrane is “stripped” to remove antibody, often with surfactant solutions at extreme pH, after the first immunoassay and then re-probed with a second antibody. Only a few proteins can be measured this way because the stripping steps remove not only antibody but also a significant amount of target protein from the membrane surface20. Re-probing also increases the total assay time because the slow immunoassay steps are performed in series21,22. An emerging alternative for multiplexed analysis is to use multiple antibodies, sometimes with different color emission, on one blot4,23; however, this technique also has limited potential to scale up beyond a few proteins. It also requires high resolution electrophoresis and high quality antibodies with no cross-reactivity. Secondary antibody cross-reactivity also exists and may require additional blocking steps.

Although MCE-based Western blotting has shown numerous advantages, little of this work has emphasized improving information content through multiplexing. One approach was to incorporate 2 antibody capture regions on a chip and drive dye-labeled proteins through these regions by electric field9. In another example, unlabeled ovalbumin (45 kDa) and beta-galactosidase (116 kDa) were resolved by MCE and then probed with different primary but the same secondary antibody to provide assay of 2 proteins per blot17.

In this report, we describe an approach to improving content by both increasing resolution, to allow cross-reactive proteins to be detected, and by producing multiple blots from a single sample for multiplexed assays. Resolution is improved by using longer electrophoresis channels. The added separation resolution is useful not only for multi-protein assays but also when cross-reactivity occurs or antibody selectivity is not known. We also demonstrate that multiple injections can be made from a single sample and deposited in separate tracks that can be probed with different antibodies in parallel. Because MCE uses such small amounts per injection, it is possible to make several injections from a single sample to increase information content. We demonstrate detection of 11 proteins from 400 ng total protein sample using this approach; although, in principle even more proteins could be measured.

Experimental Section

Reagents

FITC-protein ladder containing 7 proteins from 11 kDa–155 kDa with total protein concentration 1 mg/mL was from Invitrogen (LC5928, Grand Island, NY). Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes were from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Rabbit anti-extracellular-signal-regulated kinases (ERK) 1/2, rabbit anti-phospho-ERK1/2, rabbit anti-phospho-mitogen activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) 1/2, rabbit anti-phospho signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), and rabbit anti-phospho- protein kinase B (AKT) were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Mouse anti-MEK1/2, mouse anti-AKT, and mouse anti-STAT3 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). Mouse anti-β tubulin was from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis,MO). Jurkat cell lysates, A431 cell lysates, goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody and goat anti-mouse secondary antibody were from LI-COR Bioscience (Lincoln, NE). Unless stated otherwise, all solutions were made using Milli-Q (Millipore) 18 MΩ deionized water.

Sample Preparation

Jurkat cell lysates and A431 cell lysates were provided by LI-COR Bioscience (Lincoln, NE). Jurkat cells were stimulated by 0.2 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 15 min before lysis. A431 cells were stimulated by 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF) for 30 min at 37 °C before lysis. Cells were lysed in 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 25 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1% Triton-x 100 and 10% glycerol. Cell lysates were denatured by heating at 90 °C for 5 min in denaturation buffer consisting of 3% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 5% β mercaptoethanol (BME). For most assays, 1 μL of denatured lysate was mixed with 1 μL FITC-protein ladder, 2 μL of 100 mM Na2HPO4 buffer pH 7.5, and 6 μL water. Unless stated otherwise, the final total protein concentration was 0.24 mg/mL. To demonstrate the low-sample consumption advantage of using microchips, only 2 μL of diluted sample was loaded in the sample reservoir.

Chip Fabrication

Chips were fabricated from borofloat glass by using standard wet etching methods24–26. Briefly, 1 inch by 3 inches glass slides coated with a layer of chrome and photoresist (Telic Company, Valencia, CA) were exposed to UV light (Optical Associates, Inc., Milpitas, CA) for 5 s through a photomask (Fineline-imaging, Colorado Springs, CO) that had the desired channel network patterned in it (see Figure 1). The exposed glass was etched in HNO3 / HF / H2O (17:48:55 v:v:v) for 12.5 min resulting in channels that were 15 μm deep and 50 μm wide except the post-column channel which was 90 μm wide. Turns were added to the design in order to fit an 8.6 cm separation channel on a 5 cm long glass slide. The measured width of the channel through the arc on photomask was 10 μm. After etching, the dimensions were 40 μm wide × 15 μm deep at the arc. Access holes (0.4 or 1 mm) were drilled in the etched glass using bits from Kyocera (Costa Mesa, CA). The resulting slides were soaked in piranha solution (H2SO4 / 30% H2O2 3:1 v:v) for 20 min and then RCA solution (NH4OH / 30% H2O2 / H2O 1:1:5 v:v:v) for at least 40 min. A borofloat glass slide was thermally bonded, as a cover, to the etched glass slide in a programmable furnace (Model number 810, Evenheat Kiln, Inc., Caseville, MI). The chip was cut using an ADT 7100 series dicing saw (Horsham, PA) to create a point at the post-separation channel as shown in Figure 1. Channel lengths are indicated on Figure 1. Polyimide-coated fused silica capillaries were connected to the sheath channels using PEEK Nanoports (IDEX Health & Science, Oak Harbor, WA). Glass tubes of 0.05” i.d. were glued on the surface and served as sample reservoirs.

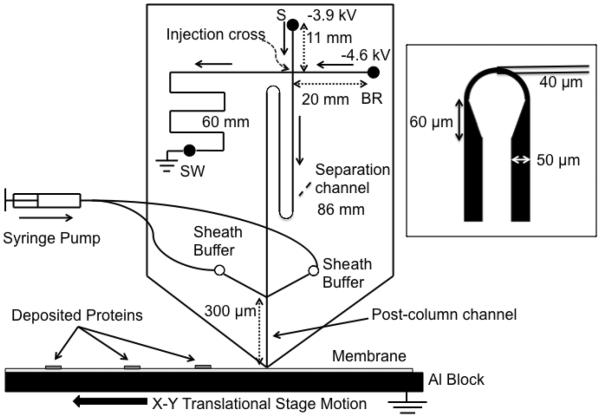

Figure 1.

Microchip overview. Sample was injected using gated injection method. SDS-protein complexes separated by size were captured in discrete zones on the PVDF membrane moving beneath the chip outlet to preserve separation information. Sieving media was pumped through the sheath channels to ensure a stable current. Channel lengths are indicated by double arrow lines and direction of flow during separation is indicated by solid, single arrows. Separation channel was between the injection cross and the end of the channel, and length was 86 mm. Drawing is not to scale. 300 μm post channel was drawn long for clarity. The inset figure shows the asymmetric turn used to reduce geometric dispersion.

Microchip gel electrophoresis preparation and operation

Channels were conditioned by sequential rinsing with 0.1 M NaOH, 0.1 M HCl, and water for 20, 15, and 10 min respectively, followed by pumping sieving media (AB Sciex, part number 390953, Framingham, MA) through the channels for 25 min. The chip was mounted on a custom-built x-y-z positioner using a 3D printed holder made of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) (see Figure S-1). The chip was positioned over a PVDF membrane that was wetted with a 1:1 v:v mixture of methanol and 100 mM Tris buffer at pH 8.8.

To perform a separation, the chip, with voltage applied as in Figure 1, was lowered toward the membrane while monitoring the current. Once the current was stable, the chip was lowered for another 20 μm to ensure a stable contact. This procedure helped ensure good protein zone formation on the membrane. If the chip was lowered 80–100 μm further into membrane, the current remained stable; but, the protein peaks captured on membrane were split and resolution was lower (see Figure S-2). These effects were due to the glass tip interfering with protein deposition.

A gated injection method was used to introduce sample into separation channel27. Referring to Figure 1, sample was injected by floating the buffer reservoir (BR) and sample waste (SW) with −3.9 kV applied to the sample reservoir (S) and grounding the Al block at the exit. During separation, flow from the sample reservoir was gated to the sample waste reservoir (SW) using the voltages as shown. During separations the sieving polymer solution was pumped through sheath flow channels at 30 nL/min. The membrane was moved at 4 mm/min during the separation.

Conventional Western blots

For some experiments, proteins in cell lysates were separated using Ready Gel® Precast Gels (Biorad, Hercules, CA). Separation voltage was 100 V and transfer voltage was 50 V. The membrane was then blocked by a blocking buffer (LI-COR Bioscience, part number 927-40000, Lincoln, NE) for 1 hour. It was then incubated with primary antibody solution overnight in a 4°C fridge. Free antibodies were washed away with 0.1 M tris-buffered saline with 0.1% tween-20 (TBST) buffer. Membrane was then incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 hour. Unless stated otherwise, primary antibodies were diluted to 1:1000 and secondary antibodies conjugated with 680 nm dye were diluted to 1:5000. All antibody solutions were diluted using blocking buffer.

Detection on Membrane

In most cases, lysate sample was mixed with FITC-protein ladder. After separation and transfer, fluorescent ladder proteins were detected on the membrane by direct imaging using a Typhoon 9410 variable mode imager (GE Healthcare) in fluorescence mode. For immunoassay, the membrane was dried at room temperature and then imaged using an Odyssey near-IR imager (LI-COR Bioscience, Lincoln, NE).

Multiplexing

When analyzing multiple proteins from one cell lysate sample, sequential injections were made from a single sample. Each separation was deposited on a different moving membrane or they were captured on separate sections of a single membrane that was then cut so that each piece could be immuno-probed separately. Each membrane strip that preserved a full separation was scanned under a fluorescent imager before immunoassay for size calibration. All membranes were then blocked and treated with different antibodies for the target proteins using the same protocol as for conventional Westerns.

Results and Discussion

Chip Design

Figure 1 illustrates the microchip used in this work. SDS-protein complexes were loaded into the sample reservoir and injected onto the 8.6 cm long electrophoresis channel for separation. The chip outlet was dragged along the surface of the membrane so that as proteins migrated from the separation channel they were deposited directly onto the membrane, similar to prior work with CE.28–30 In this way, blotting occurred automatically as the compounds migrated from the chip, which saves time compared to a traditional Western blot. Another benefit of direct transfer is to deposit all protein, regardless of size, onto membranes. In contrast, with traditional Western blot transfer methods smaller proteins may be driven through the membrane to ensure electromigration of larger, slower-moving, proteins.

Unlike prior MCE Western blot10, the chip was designed with asymmetric side channels31 (one was 20 mm and the other 60 mm) connecting the sample waste and buffer reservoir to the injection cross. These different lengths prevented over-heating of the chip when applying high voltage for the separations. For example, when the separation electric field was 400 V/cm, the electric fields in the two side channels were calculated to be 573 V/cm and 579 V/cm (Figure 1). On a chip with symmetric side channels of 20 mm long, to maintain the same separation electric field, the electric field in side channels would be higher than 1000 V/cm. Under such conditions air bubbles were formed in the channels preventing stable operation.

Improving separation resolution

Prior work with this general approach emphasized achieving rapid separations on a microchip with short separation length. We previously showed, for example, that a FITC-protein ladder containing 7 proteins from 11 kDa to 155 kDa could be separated with baseline resolution within 2 min on chips with 15 μm deep by 50 μm wide by 2 cm long channels with 460 V/cm applied10. In this work we examined increasing resolution by optimizing the channel dimensions and injection conditions.

Resolution of ERK1/2 (42/44 kDa) was used a goal. We first investigated the effects of channel depth and width on separation performance. Channels that were 9 × 28 μm, 15 × 50 μm, 19 × 58 μm, and 32 × 84 μm, all 4 cm long, were evaluated by separating a protein ladder containing 7 proteins from 11 kDa to 155 kDa using the same injection and separation voltage. Inspection of the resulting electropherograms (see Figure S-3) revealed several trends. Increasing channel size yielded a higher signal for early eluting peaks but worse separation resolution and loss of signal for larger proteins. For example, resolution (Rs, using a standard definition32) between 32 kDa and 40 kDa decreased from 1.8 ± 0.1 (n = 3) to 0.8 ± 0.3 (n = 3) when channel dimensions increased from 9 × 28 μm to 32 × 84 μm. More injection bias is also observed when using deeper and wider channels. For example, the 6th (98 kDa) and 7th (155 kDa) peak, which were detected in 9 × 28 μm and 15 × 50 μm channels, were not observed in 19 × 58 μm and 32 × 84 μm channels. These results were attributed to electric field effects within the larger injection cross33. We chose chips with 15 × 50 μm channels for further optimization. Although the smaller 9 × 28 μm channels yielded better performance, their high flow resistance made filling the channels inconvenient, e.g. conditioning time was 50 min compared to 10 min for the 15 × 50 μm chips. In principle, less viscous sieving media would allow smaller channels to be used.

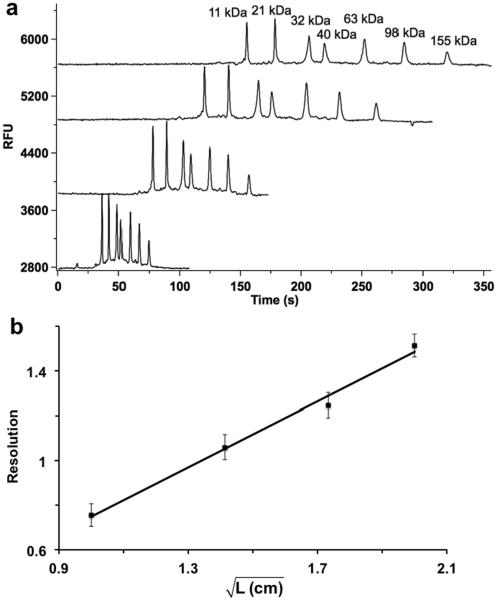

We next compared resolution of a protein ladder for separation lengths from 1 to 4 cm (Figure 2a). These experiments showed the expected trend of increased resolution linear with the square root of separation length32 (see Figure 2b). Based on this trend, we estimated that the length needed resolve proteins with a 5% difference in molecular weight (e.g. ERK1/2) was 8.6 cm. To fit an 8.6 cm long separation channel on a 5 cm long chip requires adding turns to the channel; however, turns cause geometric dispersion by the “race-track” effect34–36 where molecules move faster along the inner wall than the outer side of the channel when making the turn. In this work, an asymmetrically tapered turn was applied to minimize this source of dispersion36. The effectiveness of this approach to reduce band broadening during sieving electrophoresis was verified as shown in Figure S-4. Based on these experiments, a chip with 15 μm deep × 50 μm wide × 8.6 cm long separation channel containing 15 μm deep × 40 μm wide arcs was considered the best dimension for achieving the desired resolution.

Figure 2.

Effect of channel length on resolution of protein ladder. A fluorescently labeled protein ladder consisting of 7 proteins from 11 to 155 kDa at a total concentration of 1 mg/mL protein was injected and separated using the chip in Figure 1 while monitoring fluorescence in the channels. (a) Traces, from top to bottom, are electropherograms recorded 1 cm, 2 cm, 3 cm, and 4 cm downstream of injection cross. RFU on the Y-axis stands for relative fluorescent unit. Overlaid electropherograms are offset in Y-axis. (b) Relationship between the square root of separation length (L) and resolution between 32 kDa and 40 kDa proteins. Separation field was 400 V/cm and sample was injected using gated injection method. 3 replicates at each separation length were recorded.

Injection for Cell Lysates

After determining the channel dimensions that gave the desired resolution, the system was tested for detection of ERK1/2 in cell lysate. Initial results with a 5 s gated injection, which had been used for development, yielded faint or inconsistent signals on the membrane from Jurkat cell lysate at 2.4 mg protein/mL. Using 10 s injection times allowed ERK1/2 to be detected; but resolution was less than expected (Rs = 0.6 ± 0.2, n = 3), likely due to over injection (Figure 3a).

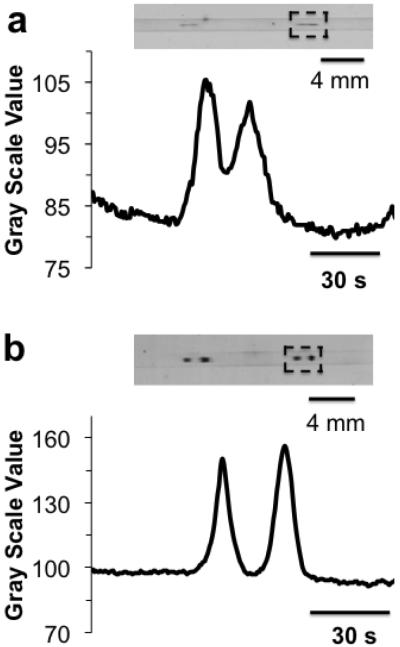

Figure 3.

Western blot assay of ERK1/2 from Jurkat cell lysate with different sample preparation. (a) 2.4 mg/mL cell lysate (results from duplicate injections are shown in blot image) and (b) diluted 1:10 (v:v) with 20 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5 so that final concentration is 0.24 mg/mL. Traces below each membrane were line scans through membrane with x-axis converted to separation time. Region of interest is boxed with black dashed lines. Sample was injected for 10 s at 390 V/cm using gated injection. Separation field was 400 V/cm over 8.6 cm separation distance.

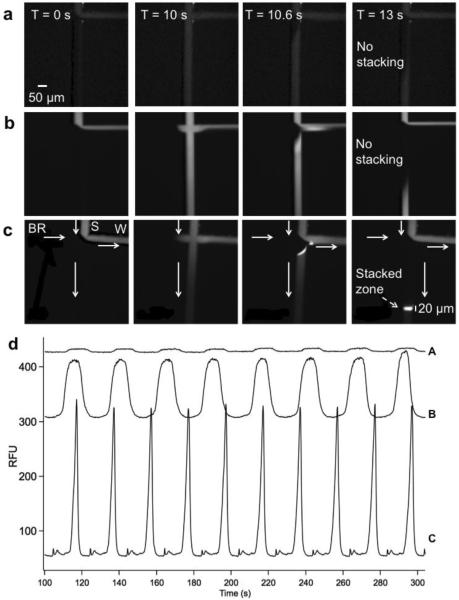

To address these issues, we evaluated use of preconcentration techniques. Specifically, we diluted samples 1:10 in 20 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.5, which allowed both field amplification sample stacking (FASS) and isotachophoresis (ITP)37,38 focusing. The injection conditions were optimized using FITC-BSA as the analyte, which allowed visualization of the injection by fluorescence microscopy. Figure 4a and 4b shows that when FITC-BSA was dissolved in low conductivity solvent (water, Figure 4b), signal increased an average of 15 ± 2 fold (n = 8) compared to diluting sample in gel (Figure 4a). This effect can be attributed to FASS as sample migrates from the sample reservoir to the injection cross. Adding 20 mM phosphate to the diluent, likely to act as leading electrolyte for transient ITP preconcentration, resulted in compression of the zone within 500 to 600 μm of the injection cross (Figure 4c). As a result, peak width decreased from 18.4 ± 1.2 s (n = 8) to 9.6 ± 0.3 s (n = 8) when diluted in phosphate. The combined effect allowed a 38 ± 1 fold (n = 8) peak height increase when FITC-BSA was diluted in 20 mM phosphate buffer rather than in gel buffer (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Sample stacking effect on injection and separation. Each set (a,b, and c) has 4 images, representing before injection (T = 0 s), during injection (T = 10 s), and after injection (T = 10.6 s and T = 13 s). They show sequence of images at injection cross of chip similar to that in Figure 1 during 10 s long injection at 390 V/cm of 0.01 mg/mL FITC-BSA diluted 1:10 in (a) the same gel buffer used for separation; (b) water; and (c) 20 mM Na2HPO4 buffer. White arrows in (c) indicate the flow direction similar to that in Figure 1. Labels in (c) show the relative position of the sample (S), buffer reservoir (BR), and waste (W). The separation channel is oriented vertical. Comparison of images in (a) and (b) show concentration of FITC-BSA due to field amplification. Images in (c) show that the 600 μm long sample plug was focused into a 20 μm wide band within 3 s but not stacked in the other conditions. (d) Comparison of multiple injection zones measured 600 μm from the injection cross when sample was diluted in (A) gel, (B) water, and (C) 20 mM Na2HPO4 pH 7.5. Overlaid electropherograms are offset in Y-axis for clarity.

As shown in Figure 3b, when cell lysate samples were diluted 1:10 in 20 mM phosphate buffer, peaks had even higher signal and were better resolved than injections made without dilution (Figure 3a) for the same time. For example, ERK2 (42 kDa) peak area was 3.5 ± 0.5 (n = 3) fold higher than using original lysate. Resolution of ERK1/2 was improved to 1.4 ± 0.1 (n = 3) compared to 0.6 ± 0.2 (n = 3) when analyzing original lysate.

The resulting separations can be compared to traditional Western blotting (see Figure S-5). For these experiments, 10 μg total protein was loaded onto a 10 cm long 10% acrylamide gel and separation was carried out at with 100 V for 1 h with an additional hour required for protein transfer. Under these conditions, ERK1 and ERK2 were separated with a resolution of 0.9. Thus, the microchip approach yielded better resolution in less time (8 min for separation and transfer), and used much less sample (400 ng loaded onto the chip).

Multiplexing Using Microchips

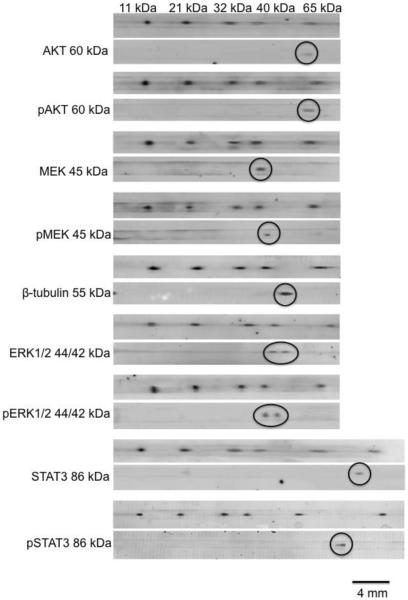

To assess the utility of the microfluidic, direct-blotting technique for detecting multiple target proteins from single cell lysate sample, we performed assays for ERK1/2, MEK1/2 (45 kDa), AKT (45 kDa), STAT3 (86 kDa), their phosphorylated forms, and beta-tubulin (55 kDa) in Jurkat cell lysate samples (Figure 5). For these experiments, 2 μL of diluted sample, corresponding to 400 ng of total protein, was loaded onto the chip. The sample was injected 9 times with each separation being deposited on a different portion of the membrane. The membrane tracks were then treated separately for each protein. ERK1 and ERK2, phospho-ERK1 and phospho-ERK2 were resolved so that a total of 11 proteins were detected in the assay. For comparison, a conventional Western blot would have required ~90 μg total protein or repetitive stripping and reblotting process, to achieve a comparable number of proteins detected.

Figure 5.

Multiplexed Western blot assays of Jurkat cell lysate by MCE. 2 μL of 0.2 mg total protein/mL cell lysate was loaded onto the chip. The same sample was injected 9 times with each trace laid on a different membrane. Each membrane was probed with a different antibody as indicated in the figure. For each assay, the membrane was scanned using a fluorescent scanner first at 488 nm/525 nm to detect FITC-protein ladder. After incubating with different antibodies, membranes were scanned at 680 nm/694 nm to detect target proteins. Band for target protein is circled. Expected molecular weights of all the proteins targeted are labeled in the figure.

These results show how a combination of added resolution and multiple injections allow multiplexed assay from a single sample. Although 11 proteins were detected in these experiments, further enhancement of the multiplexing is possible by making more injections. We have found that it is possible make 60 injections before the migration times shift significantly suggesting the potential for this many assays from a single sample10.

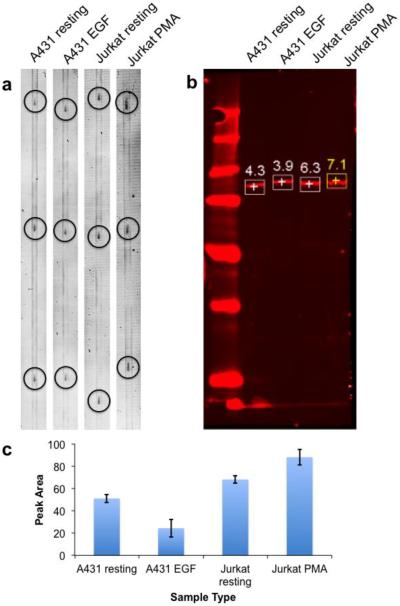

Signal reproducibility was evaluated by measuring STAT3 signal from 4 different types of cell lysates in triplicate within a day. Figure 6a and 6c shows that for multiple injections, the RSDs of STAT3 peak area were 2.6%, 7.9%, 6.8%, and 3.8% for EGF-stimulated A431, resting A431, PMA-stimulated Jurkat, and resting Jurkat lysates, respectively (n = 3). (These traces display parallel lines along the length of the track. These lines are an artifact from deposition that occurs on some traces, possibly due to the chip damaging the membrane as it dragged along the surface.)

Figure 6.

Microchip based Western blotting system repeatability study. Repeated injections were made for determination of STAT3 level in EGF-stimulated A431, resting-A431, PMA-stimulated Jurkat, and resting Jurkat cell lysate using (a) microchip based Western blotting system and (b) conventional Western blotting methods. Peaks are circled for clarity. For (a), sample was injected three times while the chip was continuously passed along the membrane. Only the portion of the membrane with detected protein is shown. For (b), numbers next to the bands represent integrated peak areas in arbitrary units. (c) Intensity of the peaks from different samples using microchip western blotting method. Error bar is ±1 standard deviation (n = 3).

The same samples were analyzed by conventional western blot to allow comparison of results from that technique. The peak area ratios are comparable to those obtained from a conventional Western blot (Figure 6b). For example, STAT3 peak area ratio between resting Jurkat lysates and resting A431 is 1.5 using traditional Western blotting and 1.7 ± 0.1 (n = 3) when using microchip Western blotting. This result shows that similar antibodies and protocols for the immunoassay step can be used with both the MCE and conventional gel-based Western. This experiment also illustrates the efficiency of sample usage for the MCE system. To achieve the triplicate injections would have required 30 μg of total protein compared to 400 ng loaded for these samples, a nearly 100-fold difference. Although the MCE method used much less sample, the S/N was lower as observed in Figure 6. This difference is because the MCE system was less efficient in using sample. In a western blot, all of the sample loaded onto the gel is injected. In contrast, on the MCE system 400 ng were loaded onto the chip; however, only a small fraction was actually injected and separated with rest remaining in the sample reservoir. We estimate that no more than 0.2 ng is used per injection. More efficient use of sample then could lead to even smaller sample usage. Our estimate of the amount of sample used is conservative because it includes what is needed to load onto the reservoir.

To further test reproducibility, more replicates were tested on a single device using ERK1/2 as a target. A total of 5 overlapping injections were made and captured on membranes (Figure S-6). Resolution between 42 kDa and 44 kDa proteins was 1.3 ± 0.2 (n = 5). ERK2 (42 kDa) peak area RSD is 3.6% (n = 5) and peak migration time is 461 ± 13 s (n = 5), showing good repeatability from multiple injections on one device. Device-to-device variability was also evaluated using FITC protein ladder by MCE. Protein ladder was injected every 2 min and separated over a 2 cm long separation channel.. Separation resolution between the 3rd (32 kDa) and 4th (40 kDa) peak in the ladder was 1.04 ± 0.1 (n = 15). Migration time of the 1st peak (11 kDa) was 74 ± 10 s (n = 15) (Figure S-7).

Conclusion

This work demonstrates a method of measuring multiple proteins from a single sample using microfluidic Western blot. The electrophoretic resolution achieved in 8 min is superior to that found on with a 1 h separation on conventional gels and obviates the need for a separate blotting step. The use of small amounts per injection allows proteins to be laid on separate tracks for different immunoassays which are then operated in parallel. The combination of added resolution and multiple injections allowed 11 proteins to be measured in 400 ng of sample. This approach uses ~0.4% of the sample that would have been required using parallel injections on conventional gels. Further multiplexing is possible suggesting the possibility of measuring complete signaling pathways and other important groups of proteins in small samples with short analysis times.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants R37 DK046960, RO1 GM102236 and 1R43GM112289-01.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement. RTK is listed as an inventor on a patent that is related to the technology described here. Licensing and commercialization of the technology could lead to royalty income.

Supporting Information Details of chip holder, data on effect of vertical placement of chip on blotting results, data on effect of channel dimensions on separation performance, sample western blot of ERK 1 and 2 for resolution comparison, and in-chip and chip-to-chip reproducibility data.

References

- (1).Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Pan W, Chen W, Jiang X. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:3974–3976. doi: 10.1021/ac1000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Pan Y, Duncombe TA, Kellenberger CA, Hammond MC, Herr AE. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:10357–10364. doi: 10.1021/ac502700b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ciaccio MF, Wagner JP, Chuu C-P, Lauffenburger DA, Jones RB. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:148–155. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).He M, Herr AE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2512–2513. doi: 10.1021/ja910164d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).He M, Herr AE. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:8177–8184. doi: 10.1021/ac901392u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).He M, Herr AE. Nat. Protoc. 2010;5:1844–1856. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hughes AJ, Herr AE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:21450–21455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207754110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Tia SQ, He M, Kim D, Herr AE. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:3581–3588. doi: 10.1021/ac200322z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Jin S, Anderson GJ, Kennedy RT. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:6073–6079. doi: 10.1021/ac400940x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Anderson GJ, M. Cipolla C, Kennedy RT. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:1350–1355. doi: 10.1021/ac102671n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).O'Neill RA, Bhamidipati A, Bi X, Deb-Basu D, Cahill L, Ferrante J, Gentalen E, Glazer M, Gossett J, Hacker K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:16153–16158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607973103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Bousse L, Mouradian S, Minalla A, Yee H, Williams K, Dubrow R. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:1207–1212. doi: 10.1021/ac0012492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Liu JK, Pan T, Woolley AT, Lee ML. Anal Chem. 2004;76:6948–6955. doi: 10.1021/ac040094l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Shadpour H, Soper SA. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:3519–3527. doi: 10.1021/ac0600398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Osiri JK, Shadpour H, Park S, Snowden BC, Chen Z-Y, Soper SA. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:4984–4992. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hughes AJ, Herr AE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:21450–21455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207754110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Hughes AJ, Lin RK, Peehl DM, Herr AE. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:5972–5977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108617109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Guther ML, De Almeida ML, Rosenberry TL, Ferguson MA. Anal Biochem. 1994;219:249–255. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kaufmann SH, Ewing CM, Shaper JH. Anal. Biochem. 1987;161:89–95. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90656-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Gallagher S, Winston SE, Fuller SA, Hurrell JG. Current Protocol in Immunology. Vol. 83. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Sennepin AD, Charpentier S, Normand T, Sarré C, Legrand A, Mollet LM. Anal. Biochem. 2009;393:129–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Increase Western Blot Throughput with Multiplex Fluorescent Detection. http://www.biorad.com/webroot/web/pdf/lsr/literature/Bulletin_5723.pdf.

- (24).Simpson PC, Woolley AT, Mathies RA. Biomed. Microdevices. 1998;1:7–26. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Harrison DJ, Fluri K, Fan ZH, Effenhauser CS, Manz A. Science. 1993;261:895–897. doi: 10.1126/science.261.5123.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Roper MG, Shackman JG, Dahlgren GM, Kennedy RT. Anal Chem. 2003;75:4711–4717. doi: 10.1021/ac0346813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Jacobson SC, Hergenroder R, Moore AW, Ramsey JM. Anal Chem. 1994;66:4127–4132. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Preisler J, Hu P, Rejtar T, Karger BL. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:4785–4795. doi: 10.1021/ac0005870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Page JS, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:497–503. doi: 10.1021/ac0156621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Chen H, Rejtar T, Andreev V, Moskovets E, Karger BL. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:2323–2331. doi: 10.1021/ac048322z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Jacobson SC, Koutny LB, Hergenroeder R, Moore AW, Jr, Ramsey JM. Anal. Chem. 1994;66:3472–3476. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Giddings JC. Unified Separation Science. Wiley-Interscience publication; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ermakov SV, Jacobson SC, Ramsey JM. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:3512–3517. doi: 10.1021/ac991474n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Culbertson CT, Jacobson SC, Ramsey JM. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:5814–5819. doi: 10.1021/ac0006268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Jacobson SC, Hergenroder R, Koutny LB, Warmack RJ, Ramsey JM. Anal. Chem. 1994;66:1107–1113. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Ramsey JD, Jacobson SC, Culbertson CT, Ramsey JM. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:3758–3764. doi: 10.1021/ac0264574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Foret F, Szoko E, Karger BL. J. Chromatogr. 1992;608:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Xu Z, Ando T, Nishine T, Arai A, Hirokawa T. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:3821–3827. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.