Abstract

The protocol of a clinical trial serves as the foundation for study planning, conduct, reporting, and appraisal. However, trial protocols and existing protocol guidelines vary greatly in content and quality. This article describes the systematic development and scope of SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) 2013, a guideline for the minimum content of a clinical trial protocol.

The 33-item SPIRIT checklist applies to protocols for all clinical trials and focuses on content rather than format. The checklist recommends a full description of what is planned; it does not prescribe how to design or conduct a trial. By providing guidance for key content, the SPIRIT recommendations aim to facilitate the drafting of high-quality protocols. Adherence to SPIRIT would also enhance the transparency and completeness of trial protocols for the benefit of investigators, trial participants, patients, sponsors, funders, research ethics committees or institutional review boards, peer reviewers, journals, trial registries, policymakers, regulators, and other key stakeholders.

The protocol of a clinical trial plays a key role in study planning, conduct, interpretation, oversight, and external review by detailing the plans from ethics approval to dissemination of results. A well-written protocol facilitates an appropriate assessment of scientific, ethical, and safety issues before a trial begins; consistency and rigor of trial conduct; and full appraisal of the conduct and results after trial completion. The importance of protocols has been emphasized by journal editors (1–6), peer reviewers (7–10), researchers (11–15), and public advocates (16).

Despite the central role of protocols, a systematic review revealed that existing guidelines for protocol content vary greatly in their scope and recommendations, seldom describe how the guidelines were developed, and rarely cite broad stakeholder involvement or empirical evidence to support their recommendations (17). These limitations may partly explain why an opportunity exists to improve the quality of protocols. Many protocols for randomized trials do not adequately describe the primary outcomes (inadequate for 25% of trials) (18, 19), treatment allocation methods (inadequate for 54% to 79%) (20, 21), use of blinding (inadequate for 9% to 34%) (21, 22), methods for reporting adverse events (inadequate for 41%) (23), components of sample size calculations (inadequate for 4% to 40%) (21, 24), data analysis plans (inadequate for 20% to 77%) (21, 24–26), publication policies (inadequate for 7%) (27), and roles of sponsors and investigators in study design or data access (inadequate for 89% to 100%) (28, 29). The problems that underlie these protocol deficiencies may in turn lead to avoidable protocol amendments, poor trial conduct, and inadequate reporting in trial publications (15, 30).

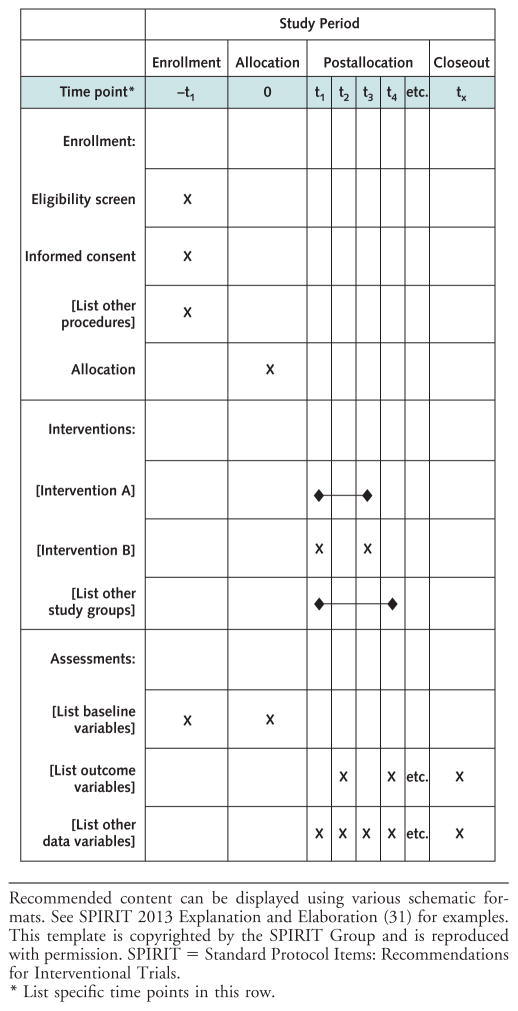

In response to these gaps in protocol content and guidance, we launched the SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) initiative in 2007. This international project aims to improve the completeness of trial protocols by producing evidence-based recommendations for a minimum set of items to be addressed in protocols. The SPIRIT 2013 Statement includes a 33-item checklist (Table 1) and diagram (Figure). An associated explanatory paper (SPIRIT 2013 Explanation and Elaboration) (31) details the rationale and supporting evidence for each checklist item, along with guidance and model examples from actual protocols.

Table 1.

SPIRIT 2013 Checklist: Recommended Items to Address in a Clinical Trial Protocol and Related Documents*

| Section/Item | Item Number | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative information | ||

|

| ||

| Title | 1 | Descriptive title identifying the study design, population, interventions, and, if applicable, trial acronym |

|

| ||

| Trial registration | 2a | Trial identifier and registry name. If not yet registered, name of intended registry. |

| 2b | All items from the World Health Organization Trial Registration Data Set (Appendix Table, available at www.annals.org) | |

|

| ||

| Protocol version | 3 | Date and version identifier |

|

| ||

| Funding | 4 | Sources and types of financial, material, and other support |

|

| ||

| Roles and responsibilities | 5a | Names, affiliations, and roles of protocol contributors |

| 5b | Name and contact information for the trial sponsor | |

| 5c | Role of study sponsor and funders, if any, in study design; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication, including whether they will have ultimate authority over any of these activities | |

| 5d | Composition, roles, and responsibilities of the coordinating center, steering committee, end point adjudication committee, data management team, and other individuals or groups overseeing the trial, if applicable (see item 21a for DMC) | |

|

| ||

| Introduction | ||

| Background and rationale | 6a | Description of research question and justification for undertaking the trial, including summary of relevant studies (published and unpublished) examining benefits and harms for each intervention |

| 6b | Explanation for choice of comparators | |

|

| ||

| Objectives | 7 | Specific objectives or hypotheses |

|

| ||

| Trial design | 8 | Description of trial design, including type of trial (e.g., parallel group, crossover, factorial, single group), allocation ratio, and framework (e.g., superiority, equivalence, noninferiority, exploratory) |

| Methods | ||

| Participants, interventions, and outcomes | ||

|

| ||

| Study setting | 9 | Description of study settings (e.g., community clinic, academic hospital) and list of countries where data will be collected. Reference to where list of study sites can be obtained |

|

| ||

| Eligibility criteria | 10 | Inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants. If applicable, eligibility criteria for study centers and individuals who will perform the interventions (e.g., surgeons, psychotherapists) |

|

| ||

| Interventions | 11a | Interventions for each group with sufficient detail to allow replication, including how and when they will be administered |

| 11b | Criteria for discontinuing or modifying allocated interventions for a given trial participant (e.g., drug dose change in response to harms, participant request, or improving/worsening disease) | |

| 11c | Strategies to improve adherence to intervention protocols, and any procedures for monitoring adherence (e.g., drug tablet return, laboratory tests) | |

| 11d | Relevant concomitant care and interventions that are permitted or prohibited during the trial | |

|

| ||

| Outcomes | 12 | Primary, secondary, and other outcomes, including the specific measurement variable (e.g., systolic blood pressure), analysis metric (e.g., change from baseline, final value, time to event), method of aggregation (e.g., median, proportion), and time point for each outcome. Explanation of the clinical relevance of chosen efficacy and harm outcomes is strongly recommended |

|

| ||

| Participant timeline | 13 | Time schedule of enrollment, interventions (including any runins and washouts), assessments, and visits for participants. A schematic diagram is highly recommended (Figure). |

|

| ||

| Sample size | 14 | Estimated number of participants needed to achieve study objectives and how it was determined, including clinical and statistical assumptions supporting any sample size calculations |

|

| ||

| Recruitment | 15 | Strategies for achieving adequate participant enrollment to reach target sample size |

|

| ||

| Assignment of interventions (for controlled trials) | ||

| Allocation Sequence generation | 16a | Method of generating the allocation sequence (e.g., computer-generated random numbers), and list of any factors for stratification. To reduce predictability of a random sequence, details of any planned restriction (e.g., blocking) should be provided in a separate document that is unavailable to those who enroll participants or assign interventions. |

| Allocation concealment mechanism | 16b | Mechanism of implementing the allocation sequence (e.g., central telephone; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes), describing any steps to conceal the sequence until interventions are assigned |

| Implementation | 16c | Who will generate the allocation sequence, who will enroll participants, and who will assign participants to interventions |

|

| ||

| Blinding (masking) | 17a | Who will be blinded after assignment to interventions (e.g., trial participants, care providers, outcome assessors, data analysts), and how |

| 17b | If blinded, circumstances under which unblinding is permissible, and procedure for revealing a participant’s allocated intervention during the trial | |

|

| ||

| Data collection, management, and analysis | ||

| Data collection methods | 18a | Plans for assessment and collection of outcome, baseline, and other trial data, including any related processes to promote data quality (e.g., duplicate measurements, training of assessors) and a description of study instruments (e.g., questionnaires, laboratory tests) along with their reliability and validity, if known. Reference to where data collection forms can be found, if not in the protocol. |

| 18b | Plans to promote participant retention and complete follow-up, including list of any outcome data to be collected for participants who discontinue or deviate from intervention protocols | |

|

| ||

| Data management | 19 | Plans for data entry, coding, security, and storage, including any related processes to promote data quality (e.g., double data entry; range checks for data values). Reference to where details of data management procedures can be found, if not in the protocol. |

|

| ||

| Statistical methods | 20a | Statistical methods for analyzing primary and secondary outcomes. Reference to where other details of the statistical analysis plan can be found, if not in the protocol. |

| 20b | Methods for any additional analyses (e.g., subgroup and adjusted analyses) | |

| 20c | Definition of analysis population relating to protocol nonadherence (e.g., as-randomized analysis), and any statistical methods to handle missing data (e.g., multiple imputation) | |

| Monitoring | ||

|

| ||

| Data monitoring | 21a | Composition of DMC; summary of its role and reporting structure; statement of whether it is independent from the sponsor and competing interests; and reference to where further details about its charter can be found, if not in the protocol. Alternatively, an explanation of why a DMC is not needed. |

| 21b | Description of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines, including who will have access to these interim results and make the final decision to terminate the trial | |

|

| ||

| Harms | 22 | Plans for collecting, assessing, reporting, and managing solicited and spontaneously reported adverse events and other unintended effects of trial interventions or trial conduct |

|

| ||

| Auditing | 23 | Frequency and procedures for auditing trial conduct, if any, and whether the process will be independent from investigators and the sponsor |

|

| ||

| Ethics and dissemination | ||

| Research ethics approval | 24 | Plans for seeking REC/IRB approval |

|

| ||

| Protocol amendments | 25 | Plans for communicating important protocol modifications (e.g., changes to eligibility criteria, outcomes, analyses) to relevant parties (e.g., investigators, RECs/IRBs, trial participants, trial registries, journals, regulators) |

|

| ||

| Consent or assent | 26a | Who will obtain informed consent or assent from potential trial participants or authorized surrogates, and how (see item 32) |

| 26b | Additional consent provisions for collection and use of participant data and biological specimens in ancillary studies, if applicable | |

|

| ||

| Confidentiality | 27 | How personal information about potential and enrolled participants will be collected, shared, and maintained in order to protect confidentiality before, during, and after the trial |

|

| ||

| Declaration of interests | 28 | Financial and other competing interests for principal investigators for the overall trial and each study site |

|

| ||

| Access to data | 29 | Statement of who will have access to the final trial data set, and disclosure of contractual agreements that limit such access for investigators |

|

| ||

| Ancillary and post-trial care | 30 | Provisions, if any, for ancillary and post-trial care, and for compensation to those who suffer harm from trial participation |

|

| ||

| Dissemination policy | 31a | Plans for investigators and sponsor to communicate trial results to participants, health care professionals, the public, and other relevant groups (e.g., via publication, reporting in results databases, or other data-sharing arrangements), including any publication restrictions |

| 31b | Authorship eligibility guidelines and any intended use of professional writers | |

| 31c | Plans, if any, for granting public access to the full protocol, participant-level data set, and statistical code | |

|

| ||

| Appendices | ||

| Informed consent materials | 32 | Model consent form and other related documentation given to participants and authorized surrogates |

|

| ||

| Biological specimens | 33 | Plans for collection, laboratory evaluation, and storage of biological specimens for genetic or molecular analysis in the current trial and for future use in ancillary studies, if applicable |

DMC = data monitoring committee; IRB = institutional review board; REC = research ethics committee; SPIRIT = Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials.

It is strongly recommended that this checklist be read in conjunction with the SPIRIT 2013 Explanation and Elaboration (31) for important clarification on the items. Amendments to the protocol should be tracked and dated. The SPIRIT checklist is copyrighted by the SPIRIT Group and is reproduced with permission.

Figure.

Example template of recommended content for the schedule of enrollment, interventions, and assessments.

Development of the SPIRIT 2013 Statement

The SPIRIT 2013 Statement was developed in broad consultation with 115 key stakeholders, including trial investigators (n = 30); health care professionals (n = 31); methodologists (n = 34); statisticians (n = 16); trial coordinators (n = 14); journal editors (n = 15); and representatives from the research ethics community (n = 17), industry and nonindustry funders (n = 7), and regulatory agencies (n = 3), whose roles are not mutually exclusive. As detailed later, the SPIRIT guideline was developed through 2 systematic reviews, a formal Delphi consensus process, 2 face-to-face consensus meetings, and pilot-testing (32).

The SPIRIT checklist evolved through several iterations. The process began with a preliminary checklist of 59 items derived from a systematic review of existing protocol guidelines (17). In 2007, 96 expert panelists from 17 low(n = 1), middle- (n = 6), and high-income (n = 10) countries refined this initial checklist over 3 iterative Del-phi consensus survey rounds by e-mail (33). Panelists rated each item on a scale of 1 (not important) to 10 (very important), suggested new items, and provided comments that were circulated in subsequent rounds. Items with a median score of 8 or higher in the final round were included, whereas those rated 5 or lower were excluded. Items rated between 5 and 8 were retained for further discussion at the consensus meetings.

After the Delphi survey, 16 members of the SPIRIT Group (named as authors of this paper) met in December 2007 in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, and 14 members met in September 2009 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, to review the survey results, discuss controversial items, and refine the draft checklist. After each meeting, the revised checklist was recirculated to the SPIRIT Group for additional feedback.

A second systematic review identified empirical evidence about the relevance of specific protocol items to trial conduct or risk of bias. The results of this review informed the decision to include or exclude items on the SPIRIT checklist. This review also provided the evidence base of studies cited in the SPIRIT 2013 Explanation and Elaboration paper (31). Some items had little or no identified empirical evidence (for example, the title) and are included in the checklist on the basis of a strong pragmatic or ethical rationale.

Finally, we pilot-tested the draft checklist in 2010 and 2011 with University of Toronto graduate students who used the document to develop trial protocols as part of a master’s-level course on clinical trial methods. Their feedback on the content, format, and usefulness of the checklist was obtained through an anonymous survey and incorporated into the final SPIRIT checklist.

Definition of a Clinical Trial Protocol

Although every study requires a protocol, the precise definition of a protocol varies among individual investigators, sponsors, and other stakeholders. For the SPIRIT initiative, the protocol is defined as a document that provides sufficient detail to enable understanding of the background, rationale, objectives, study population, interventions, methods, statistical analyses, ethical considerations, dissemination plans, and administration of the trial; replication of key aspects of trial methods and conduct; and appraisal of the trial’s scientific and ethical rigor from ethics approval to dissemination of results.

The protocol is more than a list of items. It should be a cohesive document that provides appropriate context and narrative to fully understand the elements of the trial. For example, the description of a complex intervention may need to include training materials and figures to enable replication by persons with appropriate expertise.

The full protocol must be submitted for approval by an institutional review board (IRB) or research ethics committee (34). It is recommended that trial investigators or sponsors address the SPIRIT checklist items in the protocol before submission. If the details for certain items have not yet been finalized, then this should be stated in the protocol and the items updated as they evolve.

The protocol is a “living” document that is often modified during the trial. A transparent audit trail with dates of important changes in trial design and conduct is an essential part of the scientific record. Trial investigators and sponsors are expected to adhere to the protocol as approved by the IRB and to document amendments made in the most recent protocol version. Important protocol amendments should be reported to IRBs and trial registries as they occur and subsequently be described in trial reports.

Scope of the SPIRIT 2013 Statement

The SPIRIT 2013 Statement applies to the content of a clinical trial protocol, including its appendices. A clinical trial is a prospective study in which 1 or more interventions are assigned to human participants to assess the effects on health-related outcomes. The primary scope of SPIRIT 2013 relates to randomized trials, but the same considerations substantially apply to all types of clinical trials, regardless of study design, intervention, or topic.

The SPIRIT 2013 Statement provides guidance for minimum protocol content. Certain circumstances may warrant additional protocol items. For example, a factorial study design may require specific justification; crossover trials have unique statistical considerations, such as carryover effects; and industry-sponsored trials may have additional regulatory requirements.

The protocol and its appendices are often the sole repository of detailed information relevant to every SPIRIT checklist item. Using existing trial protocols, we have been able to identify model examples of every item (31), which illustrates the feasibility of addressing all checklist items in a single protocol document. For some trials, relevant details may appear in related documents, such as statistical analysis plans, case record forms, operations manuals, or investigator contracts (35, 36). In these instances, the protocol should outline the key principles and refer to the separate documents so that their existence is known.

The SPIRIT 2013 Statement primarily relates to the content of the protocol rather than its format, which is often subject to local regulations, traditions, or standard operating procedures. Nevertheless, adherence to certain formatting conventions, such as a table of contents; section headings; glossary; list of abbreviations; list of references; and a schematic schedule of enrollment, interventions, and assessments, will facilitate protocol review (Figure).

Finally, the intent of SPIRIT 2013 is to promote transparency and a full description of what is planned—not to prescribe how a trial should be designed or conducted. The checklist should not be used to judge trial quality, because the protocol of a poorly designed trial may address all checklist items by fully describing its inadequate design features. Nevertheless, the use of SPIRIT 2013 may improve the validity and success of trials by reminding investigators about important issues to consider during the planning stages.

Relation to Existing Clinical Trial Guidance

With its systematic development process, consultation with international stakeholders, and explanatory paper citing relevant empirical evidence (31), SPIRIT 2013 builds on other international guidance applicable to clinical trial protocols. It adheres to the ethical principles mandated by the 2008 Declaration of Helsinki, particularly the requirement that the protocol address specific ethical considerations, such as competing interests (34).

In addition, SPIRIT 2013 encompasses the protocol items recommended by the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice E6 guidance, written in 1996 for clinical trials whose data are intended for submission to regulatory authorities (37). The SPIRIT Statement builds on the Good Clinical Practice guidance by providing additional recommendations on specific key protocol items (for example, allocation concealment, trial registration, and consent processes). In contrast to SPIRIT, the Good Clinical Practice guidance used informal consensus methods, has unclear contributorship, and lacks citation of supporting empirical evidence (38).

The SPIRIT 2013 Statement also supports trial registration requirements from the World Health Organization (39), the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (40), legislation pertaining to ClinicalTrials.gov (41), the European Commission (42), and others. For example, item 2b of the SPIRIT checklist recommends that the protocol list the World Health Organization Trial Registration Data Set (Appendix Table, available at www.annals.org), which is the minimum amount of information that the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors mandates for trial registries. Having this data set in its own protocol section is intended not only to serve as a form of trial summary but also to help improve the quality of information in registry entries. Registration-specific data could be easily identified in the protocol section and copied into the registry fields. In addition, protocol amendments applicable to this section could prompt investigators to update their registry data.

Appendix Table.

World Health Organization Trial Registration Data Set*

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Primary registry and trial-identifying number | Name of primary registry and the unique identifier assigned by the primary registry |

| 2. Date of registration in primary registry | Date when the trial was officially registered in the primary registry |

| 3. Secondary identifying numbers | Other identifiers, if any

|

| 4. Sources of monetary or material support | Major sources of monetary or material support for the trial (e.g., funding agency, foundation, company, institution) |

| 5. Primary sponsor | Person, organization, group, or other legal entity that takes responsibility for initiating and managing a study |

| 6. Secondary sponsor(s) | Additional persons, organizations, or other legal persons, if any, who have agreed with the primary sponsor to take on responsibilities of sponsorship |

| 7. Contact for public queries | E-mail address, telephone number, and postal address of the contact who will respond to general queries, including information about current recruitment status |

| 8. Contact for scientific queries | Name and title, e-mail address, telephone number, postal address, and affiliation of the principal investigator and e-mail address, telephone number, postal address, and affiliation of the contact for scientific queries about the trial (if applicable) |

| 9. Public title | Title intended for the lay public in easily understood language |

| 10. Scientific title | Scientific title of the study as it appears in the protocol submitted for funding and ethical review; include trial acronym, if available |

| 11. Countries of recruitment | Countries from which participants will be recruited |

| 12. Health condition(s) or problem(s) studied | Primary health condition(s) or problem(s) studied (e.g., depression, breast cancer, medication error) |

| 13. Intervention(s) | For each group of the trial, record a brief intervention name plus an intervention description Intervention name: For drugs, use the generic name; for other types of interventions, provide a brief descriptive name Intervention description: Must be sufficiently detailed for it to be possible to distinguish between the groups of a study; for example, interventions involving drugs may include dosage form, dosage, frequency, and duration |

| 14. Key inclusion and exclusion criteria | Inclusion and exclusion criteria for participant selection, including age and sex |

| 15. Study type | Method of allocation (randomized/nonrandomized) Blinding/masking (identify who is blinded) Assignment (e.g., single group, parallel, crossover, factorial) Purpose Phase (if applicable) For randomized trials: Method of sequence generation and allocation concealment |

| 16. Date of first enrollment | Anticipated or actual date of enrollment of the first participant |

| 17. Target sample size | Total number of participants to enroll |

| 18. Recruitment status | Pending: Participants are not yet being recruited or enrolled at any site Recruiting Suspended: Temporary halt in recruitment and enrollment Complete: Participants are no longer being recruited or enrolled Other |

| 19. Primary outcome(s) | The primary outcome should be the outcome used in sample size calculations or the main outcome used to determine the effects of the intervention For each primary outcome provide:

|

| 20. Key secondary outcome(s) | As for primary outcomes, for each secondary outcome provide:

|

Adapted from www.who.int/ictrp/network/trds/en/index.html.

The SPIRIT 2013 Statement mirrors applicable items from CONSORT 2010 (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) (43). Consistent wording and structure used for items common to both checklists will facilitate the transition from a SPIRIT-based protocol to a final report based on CONSORT. The SPIRIT Group has also engaged leaders of other initiatives relevant to protocol standards, such as trial registries, the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium Protocol Representation Group, and Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trials in Health-Care, to align international efforts in promoting transparency and high-quality protocol content.

Potential Effect

An extensive range of stakeholders could benefit from widespread use of the SPIRIT 2013 Statement and its explanatory paper (Table 2). Pilot-testing and informal feedback have shown that it is particularly valuable for trial investigators when they draft their protocols. It can also serve as an informational resource for new investigators, peer reviewers, and IRB members.

Table 2.

Potential Benefits and Proposed Stakeholder Actions for Supporting Adherence to SPIRIT 2013

| Stakeholder | Proposed Actions | Potential Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical trial groups, investigators, sponsors | Adopt SPIRIT as standard guidance Use as tool for writing protocols |

Improved quality, completeness, and consistency of protocol content Enhanced understanding of rationale and issues to consider for key protocol items Increased efficiency of protocol review |

| Research ethics committees/institutional review boards, funding agencies, regulatory agencies | Mandate or encourage adherence to SPIRIT for submitted protocols Use as training tool |

Improved quality, completeness, and consistency of protocol submissions Increased efficiency of review and reduction in queries about protocol requirements |

| Educators | Use SPIRIT checklist and explanatory paper as a training tool | Enhanced understanding of the rationale and issues to consider for key protocol items |

| Patients, trial participants, policymakers | Advocate use of SPIRIT by trial investigators and sponsors | Improved protocol content relevant to transparency, accountability, critical appraisal, and oversight |

| Trial registries | Encourage SPIRIT-based protocols Register full protocols to accompany results disclosure |

Improved quality of registry records Prompt for trialists to update registry record when SPIRIT checklist item 2b (Registration Data Set) is updated Improved quality, completeness, and consistency of protocol content for registries that house full protocols and results |

| Journal editors and publishers | Endorse SPIRIT as standard guidance for published and unpublished protocols Include reference to SPIRIT in instructions for authors Ask that protocols be submitted with manuscripts, circulate them to peer reviewers, and encourage authors to make them available as Web appendices |

Improved quality, completeness, and consistency of protocol content Enhanced peer review of trial manuscripts through improved protocol content, which can be used to assess protocol adherence and selective reporting Improved transparency and interpretation of trials by readers |

SPIRIT = Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials.

There is also potential benefit for trial implementation. The excessive delay from the time of protocol development to ethics approval and the start of participant recruitment remains a major concern for clinical trials (44). Improved completeness of protocols could help increase the efficiency of protocol review by reducing avoidable queries to investigators about incomplete or unclear information. With full documentation of key information and increased awareness of important considerations before the trial begins, the use of SPIRIT may also help to reduce the number and burden of subsequent protocol amendments—many of which can be avoided with careful protocol drafting and development (15). Widespread adoption of SPIRIT 2013 as a single standard by IRBs, funding agencies, regulatory agencies, and journals could simplify the work of trial investigators and sponsors, who could fulfill the common application requirements of multiple stakeholders with a single SPIRIT-based protocol. Better protocols would also help trial personnel to implement the study as the protocol authors intended.

Furthermore, adherence to SPIRIT 2013 could help ensure that protocols contain the requisite information for critical appraisal and trial interpretation. High-quality protocols can provide important information about trial methods and conduct that is not available from journals or trial registries (45–47). As a transparent record of the researchers’ original intent, comparisons of protocols with final trial reports can help to identify selective reporting of results and undisclosed amendments (48), such as changes to primary outcomes (19, 49). However, clinical trial protocols are not generally accessible to the public (45). The SPIRIT 2013 Statement will have a greater effect when protocols are publicly available to facilitate full evaluation of trial validity and applicability (11, 12, 14, 50).

The SPIRIT 2013 guideline needs the support of key stakeholders to achieve its greatest impact (Table 2), as seen with widely adopted reporting guidelines, such as CONSORT (51). We will post the names of organizations that have endorsed SPIRIT 2013 on the SPIRIT Web site (www.spirit-statement.org) and provide resources to facilitate implementation. Widespread adoption of the SPIRIT recommendations can help improve protocol drafting, content, and implementation; facilitate registration, efficiency, and appraisal of trials; and ultimately enhance transparency for the benefit of patient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Mona Loufty and Patricia Parkin for pilot-testing the SPIRIT checklist with their graduate course students. The authors also acknowledge the participation of Dr. Geneviéve Dubois-Flynn in the 2009 SPIRIT meeting.

Grant Support: Financial support for the SPIRIT meetings was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant DET-106068), National Cancer Institute of Canada (now Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute), and Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research has also funded ongoing dissemination activities (grant MET-117434).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: Dr. Krleža-Jerić was formerly employed by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Knowledge Translation Branch), and Dr. Parulekar is affiliated with the NCIC Clinical Trials Group. The funders otherwise had no input into the design and conduct of the project; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Dr. Berlin is employed by the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson, Dr. Sox is Editor Emeritus of Annals of Internal Medicine, and Dr. Rockhold is employed by GlaxoSmithKline.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M12-1905.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: A.-W. Chan, J.M. Tetzlaff, D.G. Altman, A. Laupacis, P.C. Gøtzsche, K. Krleža-Jerić, A. Hróbjartsson, H. Mann, K. Dickersin, J.A. Berlin, W.R. Parulekar, K.F. Schulz, H.C. Sox, D. Rennie, D. Moher.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: A.-W. Chan, J.M. Tetzlaff, D.G. Altman, A. Laupacis, P.C. Gøtzsche, K. Krleža-Jerić, A. Hróbjartsson, K. Dickersin, C.J. Doré, W.R. Parulekar, T. Groves, K.F. Schulz, F.W. Rockhold, D. Rennie, D. Moher.

Drafting of the article: A.-W. Chan, J.M. Tetzlaff, P.C. Gøtzsche, H. Mann, K. Dickersin, J.A. Berlin, C.J. Doré, W.R. Parulekar, K.F. Schulz.

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: A.-W. Chan, J.M. Tetzlaff, D.G. Altman, A. Laupacis, K. Krleža-Jerić, A. Hróbjartsson, H. Mann, K. Dickersin, J.A. Berlin, C.J. Doré, W.R. Parulekar, W.S.M. Summerskill, T. Groves, K.F. Schulz, H.C. Sox, F.W. Rockhold, D. Rennie, D. Moher.

Final approval of the article: A.-W. Chan, J.M. Tetzlaff, D.G. Altman, A. Laupacis, P.C. Gøtzsche, K. Krleža-Jerić, A. Hróbjartsson, H. Mann, K. Dickersin, J.A. Berlin, C.J. Doré, W.R. Parulekar, W.S.M. Summer-skill, T. Groves, K.F. Schulz, H.C. Sox, F.W. Rockhold, D. Rennie, D. Moher.

Provision of study materials or patients: K. Krleža-Jerić, K. Dickersin.

Statistical expertise: D.G. Altman, P.C. Gøtzsche, C.J. Doré, K.F. Schulz, F.W. Rockhold.

Obtaining of funding: A.-W. Chan, A. Laupacis, D. Moher.

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: A.-W. Chan, P.C. Gøtzsche, K. Krleža-Jerić.

Collection and assembly of data: A.-W. Chan, J.M. Tetzlaff, P.C. Gøtzsche, A. Hróbjartsson, K. Dickersin, C.J. Doré, W.R. Parulekar, K.F. Schulz.

References

- 1.Rennie D. Trial registration: a great idea switches from ignored to irresistible. JAMA. 2004;292:1359–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strengthening the credibility of clinical research [Editorial] Lancet. 2010;375:1225. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60523-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Summerskill W, Collingridge D, Frankish H. Protocols, probity, and publication. Lancet. 2009;373:992. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60590-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones G, Abbasi K. Trial protocols at the BMJ [Editorial] BMJ. 2004;329:1360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7479.1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groves T. Let SPIRIT take you … towards much clearer trial protocols. [on 1 October 2012];BMJ Group Blogs. 2009 Sep 25; Accessed at http://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2009/09/25/trish-groves-let-spirit-take-you-towards-much-clearer-trial-protocols/

- 6.Altman DG, Furberg CD, Grimshaw JM, Rothwell PM. Lead editorial: trials-using the opportunities of electronic publishing to improve the reporting of randomised trials [Editorial] Trials. 2006;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner EH. A taxpayer-funded clinical trials registry and results database [Editorial] PLoS Med. 2004;1:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coultas D. Ethical considerations in the interpretation and communication of clinical trial results. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:194–8. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-007GC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel JP. Editorial review of protocols for clinical trials [Letter] N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1355. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011083231921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray GD. Research governance must focus on research training. BMJ. 2001;322:1461–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan A-W. Access to clinical trial data [Editorial] BMJ. 2011;342:d80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller JD. Registering clinical trial results: the next step. JAMA. 2010;303:773–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krleža-Jerić K, Chan A-W, Dickersin K, Sim I, Grimshaw J, Gluud C. Principles for international registration of protocol information and results from human trials of health related interventions: Ottawa statement (part 1) BMJ. 2005;330:956–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7497.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lassere M, Johnson K. The power of the protocol. Lancet. 2002;360:1620–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11652-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Getz KA, Zuckerman R, Cropp AB, Hindle AL, Krauss R, Kaitin KI. Measuring the incidence, causes, and repercussions of protocol amendments. Drug Inf J. 2011;45:265–75. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Public Citizen Health Research Group v. Food and Drug Administration, 964 F Supp. 413 (DDC 1997).

- 17.Tetzlaff JM, Chan A-W, Kitchen J, Sampson M, Tricco A, Moher D. Guidelines for randomized clinical trial protocol content: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2012;1:43. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan A-W, Hróbjartsson A, Haahr MT, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG. Empirical evidence for selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials: comparison of protocols to published articles. JAMA. 2004;291:2457–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smyth RM, Kirkham JJ, Jacoby A, Altman DG, Gamble C, Williamson PR. Frequency and reasons for outcome reporting bias in clinical trials: interviews with trialists. BMJ. 2011;342:c7153. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c7153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pildal J, Chan A-W, Hróbjartsson A, Forfang E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC. Comparison of descriptions of allocation concealment in trial protocols and the published reports: cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:1049. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38414.422650.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mhaskar R, Djulbegovic B, Magazin A, Soares HP, Kumar A. Published methodological quality of randomized controlled trials does not reflect the actual quality assessed in protocols. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:602–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hróbjartsson A, Pildal J, Chan A-W, Haahr MT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC. Reporting on blinding in trial protocols and corresponding publications was often inadequate but rarely contradictory. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:967–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scharf O, Colevas AD. Adverse event reporting in publications compared with sponsor database for cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3933–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan A-W, Hróbjartsson A, Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG. Discrepancies in sample size calculations and data analyses reported in randomised trials: comparison of publications with protocols. BMJ. 2008;337:a2299. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Marzouki S, Roberts I, Evans S, Marshall T. Selective reporting in clinical trials: analysis of trial protocols accepted by The Lancet [Letter] Lancet. 2008;372:201. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernández AV, Steyerberg EW, Taylor GS, Marmarou A, Habbema JD, Maas AI. Subgroup analysis and covariate adjustment in randomized clinical trials of traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:1244–53. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000186039.57548.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Johansen HK, Haahr MT, Altman DG, Chan A-W. Constraints on publication rights in industry-initiated clinical trials [Letter] JAMA. 2006;295:1645–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Johansen HK, Haahr MT, Altman DG, Chan A-W. Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundh A, Krogsbøll LT, Gøtzsche PC. Access to data in industry-sponsored trials [Letter] Lancet. 2011;378:1995–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61871-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hopewell S, Dutton S, Yu LM, Chan A-W, Altman DG. The quality of reports of randomised trials in 2000 and 2006: comparative study of articles indexed in PubMed. BMJ. 2010;340:c723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG, Mann H, Berlin JA, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, Altman DG. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tetzlaff JM, Moher D, Chan A-W. Developing a guideline for clinical trial protocol content: Delphi consensus survey. Trials. 2012;13:176. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Medical Association. [on 1 October 2012];WMA Declaration of Helsinki-Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Accessed at www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html.

- 35.International Conference on Harmonisation. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: General Considerations for Clinical Trials: E8. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use; 17 July 1997; [on 1 October 2012]. Accessed at www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E8/Step4/E8_Guideline.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.International Conference on Harmonisation. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials: E9. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use; 5 February 1998; [on 1 October 2012]. Accessed at www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E9/Step4/E9_Guideline.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.International Conference on Harmonisation. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: Guideline for Good Clinical Practice: E6. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use; 10 June 1996; [on 1 October 2012]. Accessed at www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6_R1/Step4/E6_R1__Guideline.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grimes DA, Hubacher D, Nanda K, Schulz KF, Moher D, Altman DG. The Good Clinical Practice guideline: a bronze standard for clinical research. Lancet. 2005;366:172–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66875-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sim I, Chan A-W, Gülmezoglu AM, Evans T, Pang T. Clinical trial registration: transparency is the watchword. Lancet. 2006;367:1631–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laine C, De Angelis C, Delamothe T, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, Haug C, et al. Clinical trial registration: looking back and moving ahead [Editorial] Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:275–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-4-200708210-00166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Expanded Clinical Trial Registry Data Bank; Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007, HR 2580, 110th Congress, 1st Sess, Title VIII, §801; 2007. [on 1 October 2012]. Accessed at www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=h110-3580. [Google Scholar]

- 42.European Commission. Communication from the Commission regarding the guideline on the data fields contained in the clinical trials database provided for in Article 11 of Directive 2001/20/EC to be included in the database on medicinal products provided for in Article 57 of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 (2008/C 168/02) Official Journal of the European Union. 2008;51:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:726–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Research Council. A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. Washington, DC: National Academies Pr; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan A-W. Out of sight but not out of mind: how to search for unpublished clinical trial evidence. BMJ. 2012;344:d8013. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d8013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wieseler B, Kerekes MF, Vervoelgyi V, McGauran N, Kaiser T. Impact of document type on reporting quality of clinical drug trials: a comparison of registry reports, clinical study reports, and journal publications. BMJ. 2012;344:d8141. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d8141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reveiz L, Chan A-W, Krleža-Jerić K, Granados CE, Pinart M, Etxeandia I, et al. Reporting of methodologic information on trial registries for quality assessment: a study of trial records retrieved from the WHO search portal. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dwan K, Altman DG, Cresswell L, Blundell M, Gamble CL, Williamson PR. Comparison of protocols and registry entries to published reports for randomised controlled trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:MR000031. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000031.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, Bloom J, Chan A-W, Cronin E, et al. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.GlaxoSmithKline. Public disclosure of clinical research. [on 1 October 2012];Global Public Policy Issues. 2011 Oct; Accessed at www.gsk.com/policies/GSK-on-disclosure-of-clinical-trial-information.pdf.

- 51.Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D. Does use of the CONSORT Statement impact the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials published in medical journals? A Cochrane review. Syst Rev. 2012;1:60. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]