Abstract

The new percutaneous Impella CP (Cardiac Power; Abiomed, Inc., Danvers, MA) was designed to provide a higher level of support than Impella 2.5 (Abiomed, Inc.). We present the first documented case of a patient that was transitioned from the Impella 2.5 to Impella CP. A 48-year-old male patient with no medical history was transferred to our institution with a one day history of worsening shortness of breath. The patient was unstable and found to have monomorphic ventricular tachycardia at 220 beats/min that was cardioverted to normal sinus rhythm. An emergent right and left heart catheterization was performed showing nonobstructive coronary artery disease, biventricular failure with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 5 to 10%, high pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) 22 mm Hg, right atrial (RA) pressure 22 mm Hg, and a very low cardiac index of 1.0 L/min/m2. Because of severe cardiogenic shock, Impella 2.5 was inserted providing flow up to 2.1 L/min; however, the patient remained unstable and critically ill with severe multiorgan failure. To provide better mechanical support, the device was upgraded to the new Impella CP that can provide up to 3.5 L/min of cardiac output. Over the course of the next 72 hours, the patient showed significant improvement in hemodynamics and cardiac function (LVEF 45%), with recovery of liver function. The Impella CP was removed with no complications. The new Impella CP was shown to be safe and effective for prolonged use in critically ill patients and may significantly improve their prognosis.

Keywords: cardiogenic shock, Impella CP, nonischemic cardiomyopathy

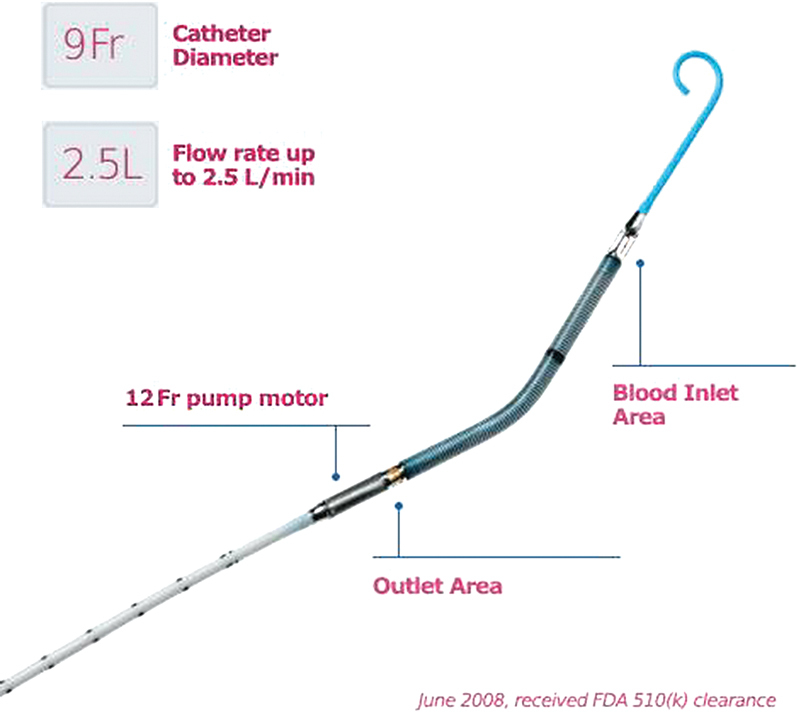

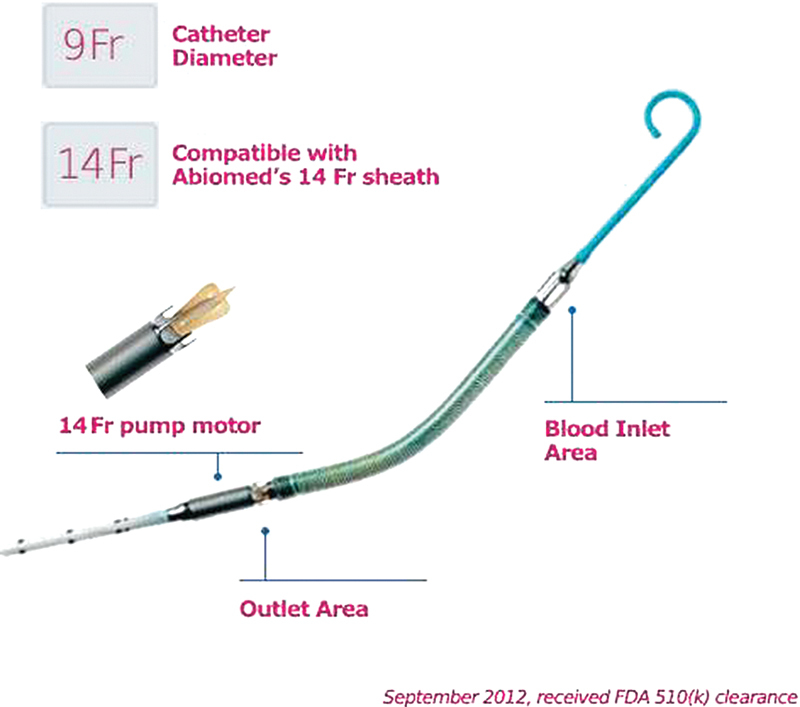

Left ventricular assist devices are commonly used in critically ill patients with cardiogenic shock to reduce the cardiac workload and provide sufficient circulation to the myocardium and vital organs. The data supporting its usage are controversial and the evidence comes mainly from registry data. The largest trial on patients with cardiogenic shock, SHOCK II trial conducted in Germany, has even shown that there is no clear benefit of using intra-aortic baloon pump (IABP) in patients with cardiogenic shock.1 Protect I and II as well as Recover I trials have shown that the new percutaneous left ventricular assist devices, Impella 2.5 (Fig. 1) and Impella 5.0 (Abiomed, Inc., Danvers, MA) (Fig. 2) respectively, are safe.2 3 4 The use of Impella 2.5 has also been shown to provide superior hemodynamic support in the setting of cardiogenic shock compared with IABP.5

Fig. 1.

Impella Model 2.5.

Fig. 2.

Impella Model 5 (CP).

The Impella 2.5 (Fig. 1) is a 12F pump mounted on a 9F catheter and is introduced percutaneously through the femoral artery using a Seldinger technique. It can provide a maximum blood flow of 2.5 L/min. In September 10, 2012, Abiomed, Inc. received clearance from the US Food and Drug Administration for a new higher flow version of its percutaneous, catheter-based Impella heart pump. The new Impella CP (Cardiac Power) (Fig. 2) is a 14F pump mounted on a 9F catheter and can provide peak blood flows of approximately 4 L/min using the same console platform as the Impella 2.5.

The Impella CP is intended for partial circulatory support using an extracorporeal bypass control unit for periods of up to 6 hours. It is also intended to provide partial circulatory support (for periods of up to 6 hours) during procedures not requiring cardiopulmonary bypass. The safety and effectiveness of the Impella CP have not been established for use in providing partial or full support of the blood circulation for periods of > 6 hours.

We present the first case of Impella CP that was transitioned from Impella 2.5 in a patient with severe cardiogenic shock due to nonischemic cardiomyopathy and used for a period of 72 hours.

Case Presentation

A 48-year-old male patient, with no medical history presented to our institution with complaints of shortness of breath and generalized weakness lasting 1 day. The patient was found to be tachycardic, and emergent electrocardiogram revealed monomorphic ventricular tachycardia with the rate of 220 beats/min. The patient became unstable and cardioversion was performed with the restoration of sinus rhythm. Because of worsening of mental status, the patient was subsequently intubated for airway protection. Initial blood work-up revealed positive troponin I with a level of 2.85 ng/mL and emergent left and right heart catheterizations were performed which revealed nonobstructive coronary artery disease, biventricular heart failure with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 5 to 10%, and high filling pressures (pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, 22 mm Hg; right atrial pressure, 22 mm Hg) with a cardiac index (CI) of 1.0 L/min/m2. Because of severe cardiogenic shock, Impella 2.5 was inserted (Figs. 3 and 4) providing up to 2.1 L/min of cardiac output (CO). The new Impella CP at the time of admission of the patient was not available in our institution. The patient's status was stabilized; however, the patient remained critically ill and developed multiorgan failure with liver shock, profound coagulopathy, and acute kidney failure requiring initiation of hemodialysis. The patient remained afebrile. Despite Impella support, the patient required additional support with epinephrine (0.2 µg/kg/min), milrinone (0.125 µg/kg/min), and vasopressin (0.2 units/min) drip. Over the course of the next 24 hours, the patient had two more episodes of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia requiring cardioversion. In addition, the patient was found to have poor peripheral circulation, faint pulses, and cold skin. Because of the instability of the patient's hemodynamic status (mean arterial pressure between 55 and 63 mm Hg), the lack of improvement in the liver function, and the risk of further complications from pressor therapy, it was decided to transition the patient to the Impella CP support (Figs. 5 and 6) after 3 days of Impella 2.5 support to provide more flow in an attempt to reverse the shock and organ failure. The patient remained on a continuous perfusion of milrinone (0.375 µg/kg/min) and a low dose of dopamine (0.25 µg/kg/min).

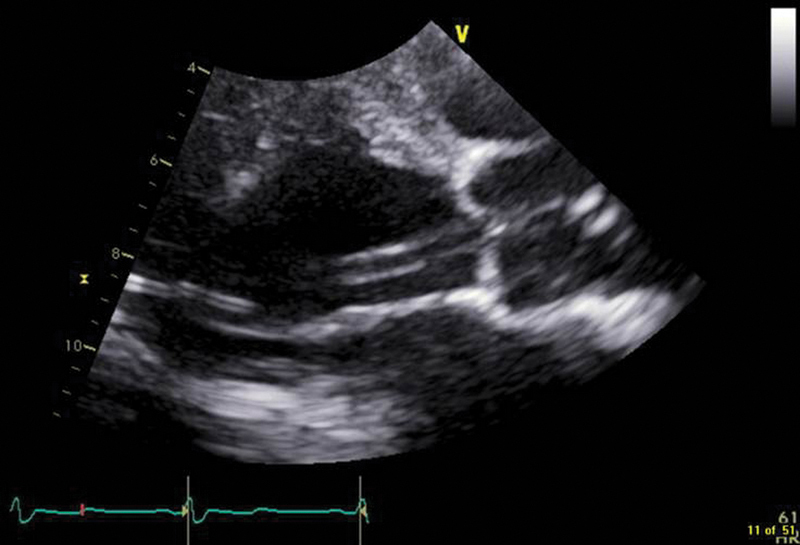

Fig. 3.

Chest X-ray, portable one view with Impella 2.5 in place.

Fig. 4.

Transthoracic echocardiography, parasternal long-axis view, with Impella 2.5 in place.

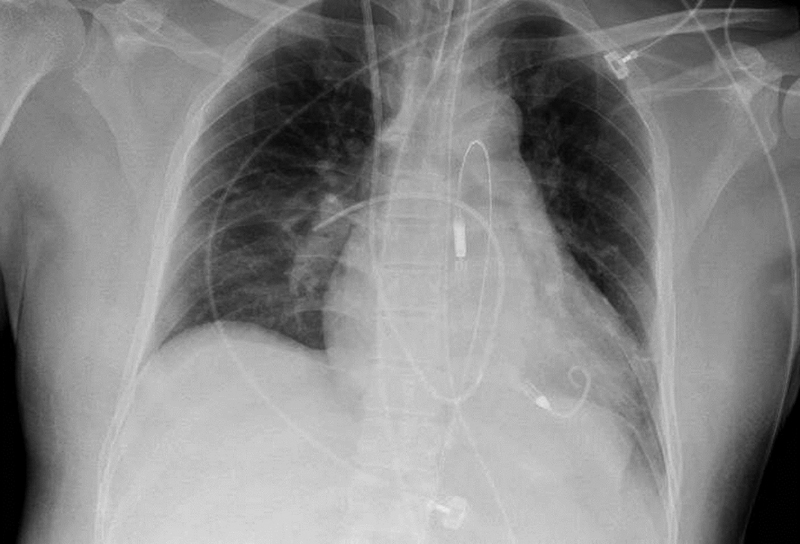

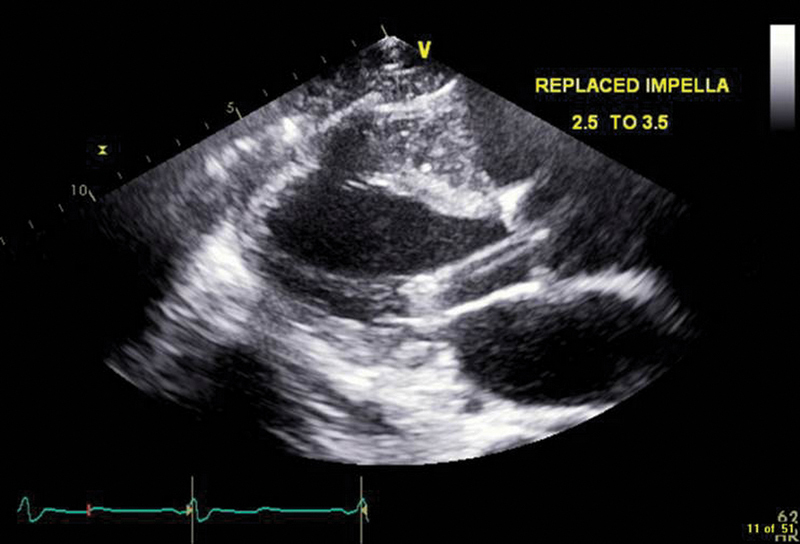

Fig. 5.

Chest X-ray, portable one view with Impella 5(CP) in place.

Fig. 6.

Transthoracic echocardiography, parasternal long axis view, with Impella 5 (CP) in place.

During that period, the work-up for an infectious etiology of myocarditis was in progress to determine the etiology of nonischemic cardiomyopathy. It was decided to start empiric treatment with steroids for the presumed diagnosis of giant cell myocarditis. Because of profound thrombocytopenia (platelets count of 27,000/mm3) and coagulopathy, the myocardial biopsy was initially postponed. With the higher level of support provided by Impella CP, the hemodynamic status of the patient remained stable with gradual improvement in CO and CI. While on Impella 2.5 as well as Impella CP support, the patient was found to have hemolysis reflected by increasing plasma free hemoglobin. The position of Impella 2.5 as well as Impella CP was evaluated daily with bedside echocardiogram and did not require repositioning. The patient received a transfusion of two units of blood during Impella support.

Over the course of the next 3 days with Impella CP support, the patient's cardiac function showed significant improvement and recovery. Repeated echocardiograms showed improvement in LVEF to 35 to 40% and hemodynamic parameters from pulmonary artery catheter showed normal filling pressures with a CO of 6 L/min and a CI of 3.5 L/min/m2. The liver function had recovered with down trending liver enzymes. The Impella CP device was successfully weaned and explanted after 72 hours of support. Hemostasis was achieved in the operating room by a vascular surgeon.

The patient's course remained stable and the patient was successfully extubated and transferred to the general medical floor. The kidney function did not fully recover, and the patient was declared to have end-stage kidney disease. The patient underwent arteriovenous fistula formation before discharge.

The myocardium biopsy did not reveal any signs of inflammatory changes in the myocardium and showed nonspecific interstitial fibrosis. The biopsy was performed after 2 weeks of steroid therapy. A cardiac magnetic resonance imaging scan was performed, but it did not reveal any specific findings. The infectious etiology work-up was also negative. The patient underwent placement of an intracardiac defibrillator as a secondary prophylaxis for ventricular tachycardia. Repeated echocardiograms after 2 weeks revealed an LVEF of 45 to 50%. There were no major complications directly related to the Impella device treatment. The patient had minor bleeding at the site of Impella device insertion, which stopped after the first day. There was ongoing hemolysis requiring transfusion of blood that did not seem to be related to malposition of the device as position was controlled with daily bedside echocardiogram. There was no vascular damage. Repeated echocardiogram after 3 weeks revealed a normal aortic valve with moderate aortic insufficiency. The patient was discharged home in stable condition.

Discussion

The new Impella CP device was designed to provide a higher level of support than Impella 2.5. The safety and efficacy of this device have not yet been established for prolonged use. To our knowledge, we report the first Impella CP case transitioned from the Impella 2.5.

Initial support with the Impella 2.5 allowed for the stabilization of the hemodynamics and delayed further degradation of the patient's status while providing a maximum flow of 2.1 L/min. The new Impella CP as well as TandemHeart (Cardiac Assist, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) was not available in our institution at the time of the presentation. There was also no data showing the safety of the new Impella CP in the treatment of patient with nonischemic cardiogenic shock for a prolonged time. However, the patient remained critically ill after 3 days of hemodynamic support with the Impella 2.5. The decision to escalate the level of hemodynamic support with the Impella CP was made to prevent the deleterious effect of increasing doses of pressors and end-organ dysfunction. The Impella CP was able to deliver a mean blood flow of up to 3.2 L/min. The patient's hemodynamics and clinical status improved markedly with the incremental flow provided by the Impella CP, reflected in Tables 1 and 2. Not only had hemodynamic parameters continuously improved from the time of insertion of the Impella CP to the time of removal of the device, but also we were able to wean Epinephrine and Vasopressin support (Table 2). In addition, no further episodes of arrhythmias requiring defibrillation occurred with the Impella CP as they had with the Impella 2.5. There were no serious complications of the device use. The patient experienced hemolysis while on Impella support and required a blood transfusion. A moderate aortic insufficiency was noted on echocardiogram after explanation of the Impella CP. Two additional episodes of ventricular tachycardia were experienced by the patient while on Impella 2.5 and epinephrine perfusion. It is uncertain whether these episodes were related to epinephrine therapy, to the Impella device use, or were related to the acute cardiomyopathy itself independent of treatment interventions. The patient experienced no episodes of arrhythmia while on Impella CP support and off epinephrine drip. The patient experienced no vascular complications related to the prolonged presence of the 9F sheath in the left femoral artery; the blood flow was not compromised. In addition, after the change in the Impella device and weaning of the epinephrine and vasopressin, the flow to the lower extremities had improved—reflected by stronger peripheral pulses and the presence of warm skin in the lower extremities.

Table 1. Indicators of multiorgan failure with no Impella support, Impella 2.5, and Impella CP.

| Pre-Impella | Impella 2.5 | Impella CP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Troponin (ng/mL) | 2.85 | 48.8 | 1.7 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.75 | 3.6a | 2.69a |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 18.6 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| pH | 7.06 | 7.41 | 7.39 |

| Bicarbonate (Meq/L) | 8 | 21 | 25 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.4 | 6.2 | 4.6 |

| AST (U/L) | > 2,250 | > 2,250 | 74 |

| ALT (U/L) | > 3,000 | > 3,000 | 985 |

| INR | 1.4 | 2.8 | 1.1 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; INR, international normalized ratio.

On continuous venovenous hemodialysis (CVVHD).

Table 2. Doses of inotrops and pressors with corresponding hemodynamic parameters.

| Pre-Impella | Impella 2.5 | Impella CP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressors and inotrops | |||

| Epinephrine (µg/kg/min) | 0.2 | 0.2 | − |

| Milrinone (µg/kg/min) | − | 0.125 | 0.375 |

| Vasopressin (units/min) | − | 0.2 | − |

| Dopamine (µg/kg/min) | − | − | 0.25 |

| Hemodynamics | |||

| MAP (mm Hg) | 55–60 | 58–62 | 70–75 |

| RAP (mm Hg) | 22 | 18 | 9 |

| PAP (mm Hg) | 28/25 (26) | 43/23 (29) | 38/17 (24) |

| PCWP (mm Hg) | 22 | 17 | 14 |

| CO (L/min) | 2 | 2.48 | 6.54 |

| CI (L/min/m2) | 1.15 | 1.43 | 3.76 |

Abbreviations: CI, cardiac index; CO, cardiac output; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; RAP right atrial pressure.

The potential complications related to the treatment with the device mentioned by the manufacturer include the occurrence of hemolysis, thrombocytopenia, bleeding, and risk of infection, as well as possible vascular complications related to both the insertion of the device as well as explanation. There is also the risk of injury to the aortic valve related to the prolonged use of the device. In this case, the patient experienced mainly hemolysis and bleeding. It is uncertain whether the aortic insufficiency was present or not before the Impella use, and therefore it is difficult to attribute with certainty the valve pathology to the device use. The bedside echocardiogram performed in the acute setting of the emergency room did not show the obvious aortic insufficiency; however, the quality of the pictures was very poor and no Doppler images were obtained at that time. Follow-up echocardiogram revealed moderate aortic insufficiency and no obvious mechanical pathology of the aortic valve. Unfortunately, no transesophageal echocardiogram or three-dimensional images were obtained to better characterize if there had been structural damage to the aortic valve. The patient had not had an echocardiogram performed before the presentation to our institution.

We present a single case report of the usage of the new Impella CP for prolonged use in a patient with cardiogenic shock because of nonischemic cardiomyopathy. While no major conclusions can be drawn from this case, it is important to demonstrate, at least, the hemodynamic benefit of the incremental flow provided by the Impella CP over the Impella 2.5 in the setting of refractory cardiogenic shock in the same patient. While this result was encouraging for our practice and may have saved our patient's life, prospective investigations will help establish whether the new Impella CP device will become the recommended standard of care in the treatment of cardiogenic shock. A valid question to consider upon reviewing this patient's course is whether the patient's status would have improved without exchange of the device due to the natural course of cardiogenic shock. However, we strongly believe that the exchange of the device provided a better level of support in our patient and was strongly indicated and crucial in the disease progression. In our opinion, insertion of the new device provided better end-organ perfusion and allowed to wean the patient from additional vasopressor support with prevention of further arrhythmias and defibrillations and was thus necessary and highly beneficial.

Conclusions

In our case, the new Impella CP was demonstrated to be safe for use and to have added incremental hemodynamic value and benefit with favorable outcome over the Impella 2.5 in the setting of prolonged use in our critically ill patient with cardiogenic shock.

References

- 1.Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann F J. et al. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(14):1287–1296. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon S R, Henriques J PS, Mauri L. et al. A prospective feasibility trial investigating the use of the Impella 2.5 system in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (The PROTECT I Trial): initial U.S. experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(2):91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Neill W W, Kleiman N S, Moses J. et al. A prospective, randomized clinical trial of hemodynamic support with Impella 2.5 versus intra-aortic balloon pump in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: the PROTECT II study. Circulation. 2012;126(14):1717–1727. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.098194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffith B P, Anderson M B, Samuels L E, Pae W E Jr, Naka Y, Frazier O H. The RECOVER I: a multicenter prospective study of Impella 5.0/LD for postcardiotomy circulatory support. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145(2):548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seyfarth M, Sibbing D, Bauer I. et al. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device versus intra-aortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock caused by myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(19):1584–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]