Abstract

Future development in spintronic devices will require an advanced control of spin currents, for example by an electric field. Here we demonstrate an approach that differs from previous proposals such as the Datta and Das modulator, and that is based on a van de Waals heterostructure of atomically thin graphene and semiconducting MoS2. Our device combines the superior spin transport properties of graphene with the strong spin–orbit coupling of MoS2 and allows switching of the spin current in the graphene channel between ON and OFF states by tuning the spin absorption into the MoS2 with a gate electrode. Our proposal holds potential for technologically relevant applications such as search engines or pattern recognition circuits, and opens possibilities towards electrical injection of spins into transition metal dichalcogenides and alike materials.

By forming heterostructures of different layered two-dimensional materials, functional spintronic devices may be built by exploiting the materials' different spin-orbit coupling and spin transport properties. Here, the authors demonstrate a spin switch in a gated structure of graphene and MoS2.

By forming heterostructures of different layered two-dimensional materials, functional spintronic devices may be built by exploiting the materials' different spin-orbit coupling and spin transport properties. Here, the authors demonstrate a spin switch in a gated structure of graphene and MoS2.

The integration of the spin degree of freedom in charge-based electronic devices has revolutionized both sensing and memory capability in microelectronics1. However, for allowing further development and a successful implementation of spin logic circuits, an electrical manipulation of spin currents is required. The approach followed so far, inspired by the seminal proposal of the Datta and Das spin modulator2, has relied on the spin–orbit field as a medium for electrical control of the spin current3,4,5,6. However, a challenge is to engineer a material that is capable of transporting spins over long distances and meanwhile has a strong enough spin–orbit coupling (SOC) to allow their electrical manipulation at temperatures above few Kelvin.

For example, carbon-based materials with intrinsic weak SOC, such as organic semiconductors7, carbon nanotubes8 and graphene9, have made a notable impact in spintronics. In particular, graphene has been proved to be ideal for long-distance spin transport (in excess of several micrometres)10,11,12,13,14,15. However, owing to its weak SOC, spin manipulation in this material has been mainly achieved by an external magnetic field through Hanle precession10,13,14. Although various approaches have been taken to enhance the SOC of graphene, for example through proximity effect16,17,18 or by atomic doping19, a direct evidence on the modulation of spin transport by an electric field remains elusive.

Meanwhile, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have emerged to complement graphene due to their unique optical, spin and valley properties20,21. Specifically, MoS2, the best-known member of that class, has a crossover from an indirect to a direct-gap semiconductor when thinned down to a monolayer (ML)22. Its electronic properties can be strongly modulated by gate, large current ON/OFF ratio as much as 1 × 108 in ML and 1 × 106 in multilayers have been found23,24. Its stronger SOC compared with that of graphene, arising from the d-orbitals of the transition metal atoms, offers new possibilities to employ the spin and valley degrees of freedom in TMDs20,25,26,27.

In our work, the combination of graphene with MoS2 in a heterostructure through weak van der Waals (vdW) forces28 allows us to engineer an alternative type of field-effect switch for spin transport. A spin current in the graphene section of the device is electrically injected from a ferromagnetic source terminal. The gate electrode controls how much of that spin current is absorbed by the intersecting MoS2 layer (spin sink) before its arrival to the ferromagnetic drain terminal. By tuning the gate voltage, we were able to switch the spin current between binary ON and OFF states at temperatures up to 200 K. The current device could be scalable and operative at room temperature, considering both the rapid progress made in chemical vapour deposition of two-dimensional (2D) materials and the theoretical performance of the materials involved.

Results

Device structure and measurement configurations

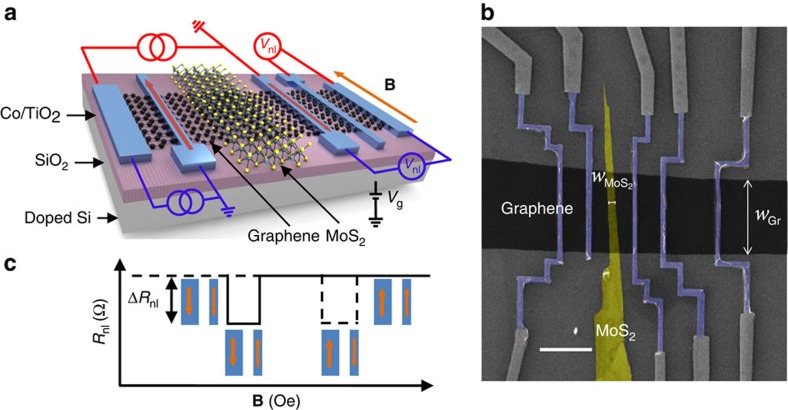

A sketch of the 2D vdW heterostructure and the electrical measurement scheme is shown in Fig. 1a, whereas a scanning electron microscope image of the device is shown in Fig. 1b. Graphene flakes are exfoliated onto a highly doped Si substrate covered by 300 nm of SiO2. An ML graphene flake is identified according to its optical contrast29 and, subsequently, a few-layer MoS2 flake is transferred above it by all-dry viscoelastic stamping30. Several Co/TiO2 electrodes are patterned by electron-beam lithography and evaporated onto the graphene channel, to create lateral spin valves (LSVs; see Methods), which enable the injection and detection of pure spin currents in graphene in a non-local geometry10,14. The non-local resistance Rnl=Vnl/I, which depends on the relative orientation of the magnetisation of the injecting and detecting Co electrodes, is measured while sweeping the magnetic field B in-plane along the easy axis of the electrodes (see Fig. 1a for a sketch of the experimental geometry). Specifically, when the configuration of the magnetizations changes from parallel to antiparallel, Rnl switches from high (Rp) to low (Rap) value. The spin signal is proportional to the amount of spin current reaching the detector, measured by ΔRnl=Rp−Rap (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1. Illustration of the experiment and scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the device.

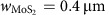

(a) Sketch of the 2D vdW heterostructure to be used for switching the spin transport. For the non-local measurement, a DC current (10 μA) is injected into graphene from a ferromagnetic Co electrode across a TiO2 barrier and a non-local voltage (Vnl) is measured by a second Co electrode while sweeping the magnetic field B. The red- and blue-coloured circuit diagrams represent the measurement configurations in the reference graphene LSV (without MoS2 on top) and the graphene/MoS2 LSV (with MoS2 intercepting the spin current path). In the latter case, the spin current flowing in the graphene can be switched ON and OFF by modulating the conductivity of MoS2 using an electric field across a SiO2 dielectric (also shown in the diagram). (b) False-coloured SEM image of the LSV devices. The width of the graphene and MoS2 are  and

and  , respectively. Scale bar, 2 μm. (c) An illustration of a typical non-local magnetoresistance measurement, where the non-local resistance Rnl switches between RP and RAP for parallel and antiparallel magnetization orientations of the Co electrodes. The spin signal is tagged as ΔRnl=Rp−Rap.

, respectively. Scale bar, 2 μm. (c) An illustration of a typical non-local magnetoresistance measurement, where the non-local resistance Rnl switches between RP and RAP for parallel and antiparallel magnetization orientations of the Co electrodes. The spin signal is tagged as ΔRnl=Rp−Rap.

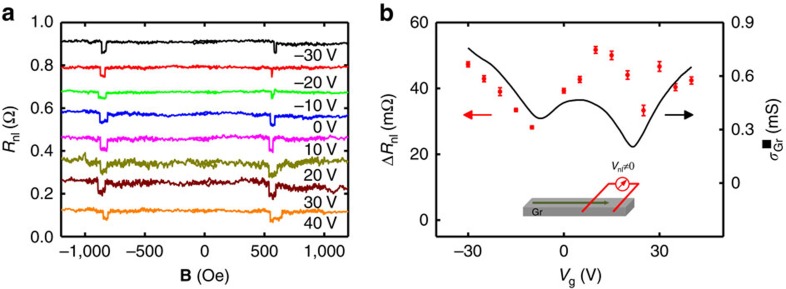

Spin transport in a reference graphene lateral spin valve

We first study the spin transport in a graphene LSV without MoS2 (reference LSV). Figure 2a shows the measured Rnl as a function of B for different gate voltages (Vg). On application of Vg, the magnitude of the spin signal weakly varies, following the modification of the graphene sheet conductivity ( ) with Vg, as can be observed in Fig. 2b. The correlation between ΔRnl and

) with Vg, as can be observed in Fig. 2b. The correlation between ΔRnl and  is a signature of a transparent interface between the Co/TiO2 electrodes and the graphene (∼250 Ω), as it is well established in the literature14.

is a signature of a transparent interface between the Co/TiO2 electrodes and the graphene (∼250 Ω), as it is well established in the literature14.

Figure 2. Spin transport in a reference graphene lateral spin valve.

Measurements are done using the red-coloured circuit diagram in Fig. 1a. (a) Non-local resistance Rnl as a function of the magnetic field B measured at different Vg at 50 K. The current bias is 10 μA and the centre-to-centre distance between ferromagnetic electrodes (L) is 1 μm. Individual sweeps are offset in Rnl for clarity. (b) Spin signal ΔRnl measured at different Vg (red circles). The black solid line shows the sheet conductivity of the graphene as a function of Vg. The inset shows schematically the spin current (green arrow) reaching the detector in the full range of Vg. Error bars are calculated using the s.e. associated with the statistical average of the non-local resistance in the parallel and antiparallel states.

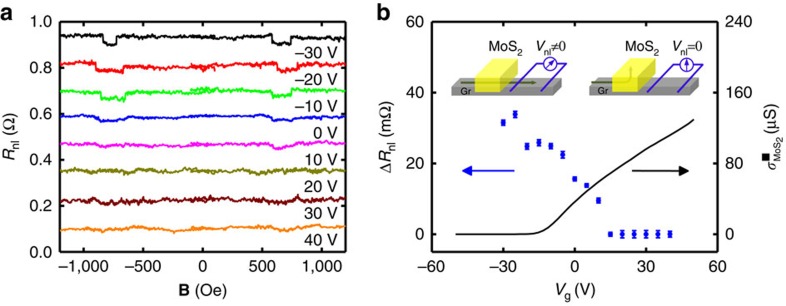

Spin transport in a graphene/MoS2 spin field-effect switch

Next, we introduce the central results of our manuscript: the demonstration of spin switching by a gate voltage in a graphene/MoS2 LSV. Figure 3a shows Rnl of this device, while sweeping B for different values of Vg, where a gradual decrease of the spin signal ΔRnl with Vg can be observed. This behaviour is clearly seen in Fig. 3b, where ΔRnl is plotted as a function of Vg, showing the decay of ΔRnl towards zero at positive values of Vg, in contrast with the weakly varying spin signal measured in the reference LSV (see Fig. 2b). Figure 3b also plots the MoS2 sheet conductivity ( ) from a reference device revealing an opposite gate voltage dependence to that of ΔRnl. For large negative Vg, the semiconducting MoS2 is in the low conductivity OFF state and the measured ΔRnl value is comparable to that of the reference LSV, reaching the ON state of the device. This result is expected, considering that the electrode spacing here is slightly longer than in the reference LSV (1.8 versus 1 μm; see Fig. 1b for comparison). Sweeping the gate voltage towards positive values brings the MoS2 towards its high conductivity ON state, where

) from a reference device revealing an opposite gate voltage dependence to that of ΔRnl. For large negative Vg, the semiconducting MoS2 is in the low conductivity OFF state and the measured ΔRnl value is comparable to that of the reference LSV, reaching the ON state of the device. This result is expected, considering that the electrode spacing here is slightly longer than in the reference LSV (1.8 versus 1 μm; see Fig. 1b for comparison). Sweeping the gate voltage towards positive values brings the MoS2 towards its high conductivity ON state, where  increases by more than six orders of magnitude compared with the OFF state. Simultaneously, the spin current reaching the detector and the corresponding ΔRnl gradually decrease towards zero (see Fig. 3b), reaching the OFF state of the device for Vg>15 V. The change in spin signal per gate voltage unit in our device is ∼0.7 mΩ V−1. The results are completely reproducible upon multiple gate voltage sweeps and temperature cycles, evidencing the robustness of the effect (Supplementary Fig. 1). Similar results to those in Fig. 3b are also observed at temperatures up to 200 K (Supplementary Fig. 2).

increases by more than six orders of magnitude compared with the OFF state. Simultaneously, the spin current reaching the detector and the corresponding ΔRnl gradually decrease towards zero (see Fig. 3b), reaching the OFF state of the device for Vg>15 V. The change in spin signal per gate voltage unit in our device is ∼0.7 mΩ V−1. The results are completely reproducible upon multiple gate voltage sweeps and temperature cycles, evidencing the robustness of the effect (Supplementary Fig. 1). Similar results to those in Fig. 3b are also observed at temperatures up to 200 K (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 3. Spin transport in a graphene/MoS2 lateral spin valve.

Measurements are done using the blue-coloured circuit diagram in Fig. 1a. (a) Non-local resistance Rnl measured as a function of the magnetic field B at different Vg at 50 K using 10 μA current bias and for a centre-to-centre distance between ferromagnetic electrodes (L) of 1.8 μm. Individual sweeps are offset in Rnl for clarity. (b) Gate modulation of the spin signal ΔRnl (blue circles). The black solid line is the sheet conductivity of the MoS2 as a function of Vg. The insets show schematically the spin current path (green arrow) in the OFF state (left inset) and the ON state (right inset) of MoS2. Error bars are calculated using the s.e. associated with the statistical average of the nonlocal resistance in the parallel and antiparallel states.

This control of the spin current directly demonstrates the 2D spin field-effect switch. This proof-of-principle effect can be enhanced by using a different dielectric, for example, layered hexagonal BN24,31, or by tuning the interface resistance between graphene and Co14.

Discussion

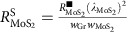

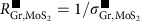

The switching of spin transport using the graphene/MoS2 vdW heterostructure relies on the absorption of spins travelling through the graphene by the MoS2, as schematically illustrated in the inset of Fig. 3b. To support this argument, we make use of the spin resistances of the channel (graphene) and the absorbing material (MoS2), which are the main control parameters in the spin absorption mechanism. Roughly, they can quantify how easily the spin current flows through each of the materials, in the same way in which one can estimate a charge current flow in parallel electrical resistors. The spin resistances of graphene and MoS2 can be expressed as  and

and  , respectively (Supplementary Note 2); where

, respectively (Supplementary Note 2); where  are their sheet resistances,

are their sheet resistances,  their spin diffusion lengths and

their spin diffusion lengths and  their widths (

their widths ( and

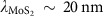

and  ). We have estimated the intrinsic spin lifetime in bulk MoS2 to be in the range of 10 ps (see Supplementary Note 2). For this estimation, we have considered electron interaction with flexural phonons and found weak temperature dependence of the spin relaxation in accord with our experimental results and in contrast to the findings in ML MoS2 (ref. 27). The lack of space inversion symmetry in a ML has two effects on the spin transport. The first one is to increase the amplitude of the spin-flip matrix element26. The second effect is to induce spin splitting of the energy bands at the K point. Although the former effect enhances spin relaxation, the latter one suppresses it when the spin splitting is large enough to exclude elastic scattering. In p-type ML TMDs, for example, the spin splitting in the valence band is of the order of hundreds of meV and the overall spin lifetime is prolonged compared with bulk. In this view, the spin degeneracy of the energy bands in few-layer TMDs renders these materials ideal spin sinks when put in proximity to graphene. Using the estimated spin lifetime in bulk MoS2, we calculate

). We have estimated the intrinsic spin lifetime in bulk MoS2 to be in the range of 10 ps (see Supplementary Note 2). For this estimation, we have considered electron interaction with flexural phonons and found weak temperature dependence of the spin relaxation in accord with our experimental results and in contrast to the findings in ML MoS2 (ref. 27). The lack of space inversion symmetry in a ML has two effects on the spin transport. The first one is to increase the amplitude of the spin-flip matrix element26. The second effect is to induce spin splitting of the energy bands at the K point. Although the former effect enhances spin relaxation, the latter one suppresses it when the spin splitting is large enough to exclude elastic scattering. In p-type ML TMDs, for example, the spin splitting in the valence band is of the order of hundreds of meV and the overall spin lifetime is prolonged compared with bulk. In this view, the spin degeneracy of the energy bands in few-layer TMDs renders these materials ideal spin sinks when put in proximity to graphene. Using the estimated spin lifetime in bulk MoS2, we calculate  in the OFF state of the device at Vg=40 V. In contrast, the spin diffusion length in graphene is much longer, being

in the OFF state of the device at Vg=40 V. In contrast, the spin diffusion length in graphene is much longer, being  estimated from Hanle measurements on a reference device (Supplementary Fig. 3). Substituting the spin diffusion lengths, the electrical properties and geometrical factors of graphene and MoS2, we obtain

estimated from Hanle measurements on a reference device (Supplementary Fig. 3). Substituting the spin diffusion lengths, the electrical properties and geometrical factors of graphene and MoS2, we obtain  and

and  Vg=40 V (Supplementary Note 2). The fact that

Vg=40 V (Supplementary Note 2). The fact that  demonstrates the capability of the MoS2 to absorb spins from the graphene channel. This is further supported by the low graphene/MoS2 barrier height at high positive Vg (ref. 32), making the interface resistance sufficiently low for efficient spin absorption.

demonstrates the capability of the MoS2 to absorb spins from the graphene channel. This is further supported by the low graphene/MoS2 barrier height at high positive Vg (ref. 32), making the interface resistance sufficiently low for efficient spin absorption.

The situation completely changes when the gate voltage Vg is swept towards negative values. At Vg=−30 V, the MoS2 conductivity  decreases by more than six orders of magnitude from Vg=40 V, which leads to a similar increase in

decreases by more than six orders of magnitude from Vg=40 V, which leads to a similar increase in  . Therefore, we have

. Therefore, we have  , preventing spin absorption by MoS2. Although the very large spin resistance of MoS2 alone is sufficient to support the vanishing spin absorption, we note that the interface resistance between graphene and MoS2 also increases32, further preventing probable spin absorption into the MoS2. Therefore, the gate dependence of the graphene/MoS2 interface resistance acts as a positive feedback, further improving the performance in the regime between the fully ON and OFF state of the device.

, preventing spin absorption by MoS2. Although the very large spin resistance of MoS2 alone is sufficient to support the vanishing spin absorption, we note that the interface resistance between graphene and MoS2 also increases32, further preventing probable spin absorption into the MoS2. Therefore, the gate dependence of the graphene/MoS2 interface resistance acts as a positive feedback, further improving the performance in the regime between the fully ON and OFF state of the device.

The inverse correlation between the spin signal ΔRnl and the MoS2 conductivity  can be clearly seen in Fig. 3b. This correlation supports the aforementioned argument and discards other scenarios, such as spin dephasing in possible trap states at the graphene/MoS2 interface. The fact that similar results to those in Fig. 3b are also observed at 200 K indicates that the effect barely changes with temperature and therefore is incompatible with the exponential temperature dependence expected for capture and escape in trap states (Supplementary Note 1). Next, we confirm the spin absorption mechanism by computing the expected spin signal ratio,

can be clearly seen in Fig. 3b. This correlation supports the aforementioned argument and discards other scenarios, such as spin dephasing in possible trap states at the graphene/MoS2 interface. The fact that similar results to those in Fig. 3b are also observed at 200 K indicates that the effect barely changes with temperature and therefore is incompatible with the exponential temperature dependence expected for capture and escape in trap states (Supplementary Note 1). Next, we confirm the spin absorption mechanism by computing the expected spin signal ratio,  , which quantifies the relative amount of spins deviating from the graphene channel towards the MoS2 (ref. 33):

, which quantifies the relative amount of spins deviating from the graphene channel towards the MoS2 (ref. 33):

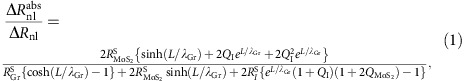

|

where  and ΔRnl are the spin signals with and without spin absorption by the MoS2;

and ΔRnl are the spin signals with and without spin absorption by the MoS2;  is the spin resistance of the Co/TiO2/graphene interface, RI is the interface resistance and PI is the interface spin polarisation; and finally,

is the spin resistance of the Co/TiO2/graphene interface, RI is the interface resistance and PI is the interface spin polarisation; and finally,  and

and  . Assuming the interface is transparent at 40 V, one can calculate the expected spin signal ratio when the MoS2 is fully ON. Substituting the known parameters into equation (1), one gets

. Assuming the interface is transparent at 40 V, one can calculate the expected spin signal ratio when the MoS2 is fully ON. Substituting the known parameters into equation (1), one gets  at Vg=40 V (Supplementary Note 3). The very small value calculated for

at Vg=40 V (Supplementary Note 3). The very small value calculated for  predicts a strong spin absorption, which confirms this scenario to be responsible for the observed experimental results of Fig. 3b.

predicts a strong spin absorption, which confirms this scenario to be responsible for the observed experimental results of Fig. 3b.

Compared with previous Datta and Das-like spin modulators3,4,5,6, the electrical manipulation of spin transport in our 2D spin field-effect switch is observed at much higher temperature (up to 200 K versus few or sub K). It also displays well-defined ON and OFF states, which are easily controlled by the gate electric field instead of an oscillatory spin signal. Moreover, there is plenty of room for the optimization of the device performance. For instance, by incorporating tunnel barriers with higher resistance, the spin signal and thus the difference between the ON and OFF states could be increased by two orders of magnitude34,35,36. The threshold voltage required to turn ON and OFF the device can be reduced by replacing SiO2 with a thinner dielectric of larger dielectric constant, such as HfO2 (ref. 37) or hexagonal BN24,31. With the above improvements to the fabrication process, and considering the robust performance of MoS2 transistors at room temperature23,24, a room-temperature 2D spin field-effect switch is envisioned. The recent advances in chemical growth of high quality 2D layered materials21,38 and their heterostructure multilayers39,40,41, as well as in homostructural42, and heterostructural36 tunnel barriers for spin injection, may well lead to large-scale integration of the current device architecture. Aside from the potential technological applications, the spin absorption effect in our experiments provides a solution to electrically inject spins into 2D semiconducting TMDs, which has so far been elusive due to the conductivity mismatch problem43,44,45.

In conclusion, the seamless integration of two 2D layered materials with remarkably different spin–orbit coupling amplitudes leads to a device capable of both transporting and electrically controlling a spin current. The demonstrated 2D spin field-effect switch can improve the performance of search engines or pattern recognition circuits, wherein a large number of independent logic operations are executed in parallel15,46,47. Furthermore, the vdW heterostructure at the core of our experiments opens the path for fundamental research of exotic transport properties predicted for TMDs20,25,26.

Methods

Device fabrication

Fabrication of ML graphene samples uses the mechanical exfoliation method initiated in ref. 29. We first exfoliate bulk graphitic crystals onto a Nitto tape (Nitto SPV 224P) and repeat the cleavage process between three and five times until thin flakes can be identified visually by the eye. The Nitto tape with relatively thin flakes is pressed against a preheated Si substrate with 300 nm SiO2. After peeling off the Nitto tape, the substrate is examined under an optical microscope and ML graphene is identified by well-established optical contrast. We then prepare the MoS2/poly-dimethyl siloxane stamp following ref. 30. First, a MoS2 crystal is exfoliated twice using the Nitto tape and transferred on to a piece of poly-dimethyl siloxane (Gelpak PF GEL film WF × 4, 17 mil.). After identifying the desired few-layer MoS2 flake using optical contrast, it is transferred on top of graphene after slowly removing the viscoelastic stamp.

The lateral spin valve is formed following a standard nanofabrication procedure including electron-beam lithography, metal deposition and metal lift-off in acetone. 5 Å of Ti are deposited by electron-beam evaporation and left to oxidize in air for 0.5 h before depositing 35 nm of Co using electron-beam evaporation.

Electrical measurements

The measurements are performed in a Physical Property Measurement System by Quantum Design, using a ‘DC reversal' technique with a Keithley 2182, nanovoltmeter and a 6221 current source. A current bias of 10 μA is used unless stated in the text. Gate voltage is applied using a Keithley model 2636. The gate voltage is applied between the back of the doped Si substrate and the grounding electrode. As graphene layer on the bottom is ML, it does not fully screen the gate electric field. Therefore, the gate voltage modulates the charge carrier density in both graphene and the MoS2.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Yan, W. et al. A two-dimensional spin field-effect switch. Nat. Commun. 7, 13372 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13372 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-4, Supplementary Notes 1-3 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

The work at CIC nanoGUNE was supported by the European Union 7th Framework Programme under the Marie Curie Actions (607904-13-SPINOGRAPH) and the European Research Council (257654-SPINTROS), by the Spanish MINECO under Project Number MAT2015-65159-R and by the Basque Government under Project Number PC2015-1-01. The work at the University of Rochester was supported by the Department of Energy under Contract Number DE-SC0014349, National Science Foundation under Contract Number DMR-1503601 and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency under Contract Number HDTRA1-13-1-0013.

Footnotes

Author contributions F.C. conceived the study. W.Y., O.T. and R.L. performed the experiments. W.Y, O.T., L.E.H. and F.C. and analysed the data, discussed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. H.D. performed theoretical calculations on the spin relaxation properties of MoS2. All the authors contributed to the scientific discussion and manuscript revision. L.E.H. and F.C. co-supervised the work.

References

- Fert A. Nobel lecture: origin, development, and future of spintronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1517–1530 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S. & Das B. Electronic analog of the electro-optic modulator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 56, 665–667 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Koo H. C. et al. Control of spin precession in a spin-injected field effect transistor. Science 325, 1515–1518 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang P. et al. All-electric all-semiconductor spin field-effect transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 35–39 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich J. et al. Spin Hall effect transistor. Science 330, 1801–1804 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi W. Y. et al. Electrical detection of coherent spin precession using the ballistic intrinsic spin Hall effect. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 666–670 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dediu A. V., Hueso L. E., Bergenti I. & Taliani C. Spin routes in organic semiconductors. Nat. Mater. 8, 707–716 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueso L. E. et al. Transformation of spin information into large electrical signals using carbon nanotubes. Nature 445, 410–413 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesin D. & MacDonald A. H. Spintronics and pseudospintronics in graphene and topological insulators. Nat. Mater. 11, 409–416 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombros N. et al. Electronic spin transport and spin precession in single graphene layers at room temperature. Nature 448, 571–574 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W. et al. Long spin diffusion length in few-layer graphene flakes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 147201 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlubak B. et al. Highy efficient spin transport in epitaxial graphene on SiC. Nat. Phys. 8, 557–561 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Han W., Kawakami R. K., Gmitra M. & Fabian J. Graphene spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 794–807 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W. et al. Tunneling spin injection into single layer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 167202 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H. et al. Experimental demonstration of XOR operation in graphene magnetologic gates at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Appl. 5, 044003 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. et al. Strong interface-induced spin-orbit coupling in graphene on WS2. Nat. Commun. 6, 8339 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calleja F. et al. Spatical variation of a giant spin-orbit effect induces electron confinement in graphene on Pb islands. Nat. Phys. 11, 43–47 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Avsar A. et al. Spin-orbit proximity effect in graphene. Nat. Commun. 5, 4875 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan J., Koon G. K. W., Jaiswall M., Castro Neto A. H. & Özyilmaz B. Colossal enhancement of the spin-orbit coupling in weakly hydrogenated graphene. Nat. Phys. 9, 284–287 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Yao W., Xiao D. & Heinz T. F. Spin and pseudospins in layered transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Phys. 10, 343–350 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh K., Kis A., Coleman J. N. & Strano M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak K. F., Lee C., Hone J., Shan J. & Heinz T. F. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radisavljevic B., Radenovic A., Brivio J., Giacometti V. & Kis A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Txoperena O. Spin injection in two-dimensional layered materials. PhD thesis, University of the Basque Country, Spain. http://www.nanogune.eu/publications/p-1-phd-theses/2016?idThesis=73 (2016).

- Xiao D., Liu G.-B., Feng W., Xu X. & Yao W. Coupled spin and valley physics in monolayers of MoS2 and other group-VI dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 196802 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. & Dery H. Transport theory of monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenides through symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 026601 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. et al. Long-lived nanosecond spin relaxation and spin coherence of electrons in monolayer MoS2 and WS2. Nat. Phys. 11, 830–834 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Geim A. K. & Grigorieva I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 449, 419–425 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Gomez A. et al. Deterministic transfer of two-dimensional materials by all-dry viscoelastic stamping. 2D Mater. 1, 011002 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Lee G-H. et al. Flexible and transparent MoS2 field-effect transistors on hexagonal Boron Nitride-graphene Heterostructures. ACS Nano 7, 7931–7936 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X. et al. Multi-terminal transport measurements of MoS2 using a van der Waals heterostructure device platform. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 534–540 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niimi Y. et al. Giant spin Hall induced by skew scattering from Bismuth impurities inside thin film CuBi alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 156602 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drögeler M. et al. Spin lifetimes exceeding 12 ns in graphene nonlocal spin valve devices. Nano Lett. 16, 3533–3539 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingla-Aynés J., Meijerink R. J. & van Wees B. J. Eighty-eight percent directional guiding of spin currents with 90 μm relaxation length in bilayer graphene using carrier drift. Nano Lett. 16, 4825–4830 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamalakar M. V. et al. Enhanced tunnel spin injection into graphene using chemical vapour deposited hexagonal boron nitride. Sci. Rep. 4, 6146 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar S. High Permittivity Gate Dielectric Materials Springer (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Kamalakar M. V., Groenveld C., Dankert A. & Dash S. P. Long distance spin communication in chemical vapour deposited graphene. Nat. Commun. 6, 6766 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. et al. Direct growth of graphene/hexagonal Boron Nitride stacked layers. Nano Lett. 11, 2032–2037 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. et al. Direct growth of large-area graphene and boron nitride heterostructures by a co-segregation method. Nat. Commun. 6, 6519 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary K. M. et al. Large-area synthesis of continuous and uniform MoS2 monolayer films on graphene. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 6449–6454 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A. L. et al. Homoepitaxial tunnel barriers with functionalized graphene-on-graphene for charge and spin transport. Nat. Commun. 5, 3161 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-R. et al. Control of schottky barriers in single layer MoS2 transistors with ferromagnetic contacts. Nano Lett. 13, 3106–3110 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dankert A., Langouche L., Kamalakar M. V. & Dash S. P. High-performance molybdenum disulfide field-effect transistors with spin tunnel contacts. ACS Nano 8, 476–482 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. et al. Controllable schottky barriers between MoS2 and Permalloy. Sci. Rep. 4, 6928 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dery H. et al. Nanospintronics based on magnetologic gates. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 59, 259–262 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. & Jiang Z. Magnetic content addressable memory. IEEE Trans. Mag. 43, 2355–2357 (2007). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-4, Supplementary Notes 1-3 and Supplementary References

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are available from the authors.