Abstract

Although female sex workers are known to be vulnerable to HIV infection, little is known about the epidemiology of HIV infection among this high-risk population in the United States. We systematically identified and critically assessed published studies reporting HIV prevalence among female sex workers in the United States. We searched for and included original English-language articles reporting data on the prevalence of HIV as determined by testing at least 50 females who exchanged sexual practices for money or drugs. We did not apply any restrictions on date of publication. We included 14 studies from 1987 to 2013 that reported HIV prevalence for a total of 3975 adult female sex workers. Only two of the 14 studies were conducted in the last 10 years. The pooled estimate of HIV prevalence was 17.3 % (95 % CI 13.5–21.9 %); however, the prevalence of HIV across individual studies varied considerably (ranging from 0.3 to 32 %) and statistical heterogeneity was substantial (I2 = 0.89, Q = 123; p < 0.001). Although the variance across the 14 studies was high, prevalence was generally high (10 % or greater in 11 of the 14 included studies). Very few studies have documented the prevalence of HIV among female sex workers in the United States; however, the available evidence does suggest that HIV prevalence among this vulnerable population is high.

Keywords: Female sex workers, HIV, United States, Review

Introduction

Based on the latest available data, the rate of diagnosis for HIV infection among women in the United States decreased from 9.5 per 100,000 persons in 2008 [1] to 6.1 per 100,000 in 2014 [2]. However, there may be subgroups among the female population where HIV transmission remains high, such as female sex workers. Globally, sex workers are among the populations most affected by HIV. A systematic review of HIV infection among female sex workers in developing countries found an overall prevalence of 11.8 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 11.6–12.0), a level that is significantly greater than in the general female population (Odds Ratio: 13.5 [95 % CI 10.0–18.1]) [3]. A recent update to this systematic review included additional data from 2011 to 2013 and showed that the estimated prevalence varied widely by region from 0.3 % (95 % CI 0.1–0.8) in the Middle East and North Africa to 29.3 % (95 % CI 25.0–33.8) in Sub-Saharan Africa. The estimated HIV prevalence in high income countries was 1.8 % (95 % CI 0.8–3.1) [4]. Despite extensive research [4–6] and ongoing HIV surveillance among female sex workers internationally [7], there have been few studies among this high-risk population in the United States and our understanding of the burden of HIV among them is limited.

Behavioral studies from the United States and around the world have often found several sources of risk among female sex workers. For example, female sex workers often have large numbers of sex partners, concurrency of partners, report infrequent or inconsistent condom use, and are likely to engage in high-risk sexual acts such as condomless anal sex [8–13]. Data from the continental United States and Puerto Rico show that sex workers are more likely than other women to have a history of sexually transmitted infections (STI) [14–16], and STI contribute to increased likelihood of acquiring and transmitting HIV [17]. Studies from the United States have also documented a high prevalence of injection and non-injection drug use among women who engage in exchange sex [18, 19]. Not surprisingly, female sex workers who inject drugs are at higher risk of HIV infection when compared to female sex workers who do not inject drugs since they can acquire HIV through sex without condoms and through sharing needles or other injection equipment. Women who abuse drugs or alcohol may feel more pressure to have condomless sex if offered more money or drugs by their clients. They may also trade sex while under the influence and receive less money when selling sex [20].

Structural risk factors for HIV infection include work environment, poverty, stigma, discrimination, and criminalization of sex work which increase the risk for HIV infection among sex workers by creating barriers to accessing HIV care and prevention services [5, 18, 21–25]. The settings where sex work occurs have a large impact on vulnerability by making it harder to negotiate condom use, find protection from violence, and have access to HIV prevention, treatment and sexual health services, including STI treatment, condoms and contraception [26]. For example, a study in Kenya found that street-based sex workers had a higher prevalence of HIV when compared to women working in fixed establishments [27]. In Miami, sex workers did not seek healthcare out of fear of discrimination and arrest [25]. Finally, there are important barriers associated with accessing prevention services as a result of the anti-prostitution laws in 49 of 50 states in the United States. Federal and local policies may discourage researchers and programs from providing services to this population [28].

The findings of systematic reviews have improved characterization of HIV burden in other parts of the world and in populations who are most at risk for HIV, including men who have sex with men, transgender women and female sex workers in international settings [3, 29, 30]. To date, however, no systematic reviews of the burden of HIV among female sex workers in the United States have been published and the burden of HIV among this population remains poorly understood. The purpose of this systematic review is to characterize the prevalence of, and risk factors for, HIV infection among female sex workers in the United States.

Methods

Search Strategy

A qualified investigator searched the following electronic bibliographic databases from inception to March 14, 2014: PubMed; EMBASE; MEDLINE; PsychINFO; PubMed; and POPLINE. Key search terms included terminology for “prostitute” or “sex worker”; “HIV” or “sexually transmitted infection”; and “epidemiology”, “prevalence”, or “incidence”. Initially, we developed the search strategy using syntax from the National Library of Medicines “Medline”. Other electronic bibliographic databases were then searched separately using parallel, database specific syntax. Citations for identified articles were imported into a central bibliographic database where deduplication was performed. Citations were then screened by title and abstract against a set of retrieval criteria (listed below under “Study Selection”). Full-length copies of all articles meeting these retrieval criteria were obtained. For quality control purposes, ten percent of articles were randomly evaluated by a second reviewer.

In addition to searches of electronic bibliographic databases, hand searches were also performed. We searched the web sites of the following organizations known to publish on HIV/AIDS research because these sources of ‘grey’ literature are not indexed in bibliographic databases.1 We also reviewed the tables of contents of journals that publish HIV/AIDS research and bibliographies of relevant publications.

We utilized Institute of Medicine guidelines [31] for protocol development and PRISMA guidelines for reporting [32]. We retrieved items that appeared to potentially meet inclusion criteria based on title and abstract (see box). All retrieved full-length articles were evaluated for inclusion in the evidence base against a list of inclusion criteria independently by two trained reviewers. A third reviewer facilitated article reassessment and discussion to resolve conflicts. In summary, we included English-language articles with original relevant quantitative data on the prevalence of HIV collected from a sample of at least 50 female sex workers in the United States. We defined sex work as exchanging sex for money, drugs, or goods. We only included articles that determined HIV infection using diagnostic tests for HIV antibodies using blood or oral specimens. We verified these criteria were satisfied when we reviewed full-length articles and ensured no duplicate data (same data reported in more than one article) were extracted by comparing authors, dates of data collection, study location, and sample size. When we did identify duplicate data, we selected the publication with the largest sample size, more complete reporting or which was most recent. We did not apply any restrictions on date of publication. This review used secondary data available publicly with no interaction with human subjects. Consequently, no ethics review was necessary or conducted.

Box. Study inclusion criteria, systematic review of HIV prevalence among female sex workers in the US.

Conducted in United States or a dependent area

Published in English language

Enrolled at least 50 female sex workers

HIV prevalence based on HIV test administered during the study

Original, non-duplicate data

Data Collection

Data were extracted onto standardized forms by a single experienced research analyst and all entries were audited for accuracy by a second author.

Analysis

We extracted and assessed HIV prevalence estimates from all included studies as if they were descriptive, cross-sectional studies. Two of the included studies had longitudinal experimental designs intended to assess other outcomes [18, 33] and one was an observational cohort study [8]; from these, we collected baseline HIV prevalence data. We critically evaluated each included study to assess the likelihood that the prevalence estimates reported might be biased using the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies [34]. The criteria in the tool assess the following issues: representativeness, recruitment, sample size, description and reporting of study subjects and setting, data coverage of the identified sample, condition measured reliably and objectively, statistical analysis, and confounding factors.

In order to estimate a weighted-mean estimate of prevalence across all included studies, prevalence estimates reported by each study were pooled using a random-effects meta-analysis model [35]. A random effects model was chosen because the characteristics of the sex workers and work settings differed considerably across included studies. As a consequence, we did not expect that the prevalence estimates would be homogeneous. Homogeneity was tested using both I2 and the Q-statistic [36, 37]. Tests of homogeneity assess whether differences between studies included in a meta-analysis can be explained by chance alone. An I2 value of 50 % or greater and/or a Q-statistic value of p<0.05 suggests the presence of heterogeneity, which means that differences in the point estimates reported by the included studies are greater than one would expect due to chance alone and pooling of these data using a fixed-effects meta-analysis would be invalid. We attempted to explain heterogeneity using an unrestricted maximum likelihood mixed effects meta-regression analysis [38]. Covariates considered in these exploratory analyses included: injection drug use; sex with injection drug users; any drug use; anal sex; condom use; age; number of sex partners; duration of sex work; race; ethnicity.

To assess the robustness of our findings, we performed a series of sensitivity analyses [39, 40]. These sensitivity analyses included an influence analysis (removing one study from the meta-analysis at a time) to assess whether any single study was particularly influential in contributing to the overall summary prevalence estimate. All meta-analysis and meta-regression was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 3.0 (Biostat, Englewood New Jersey). Number of studies is denoted by “k” and number of subjects by “n”.

Results

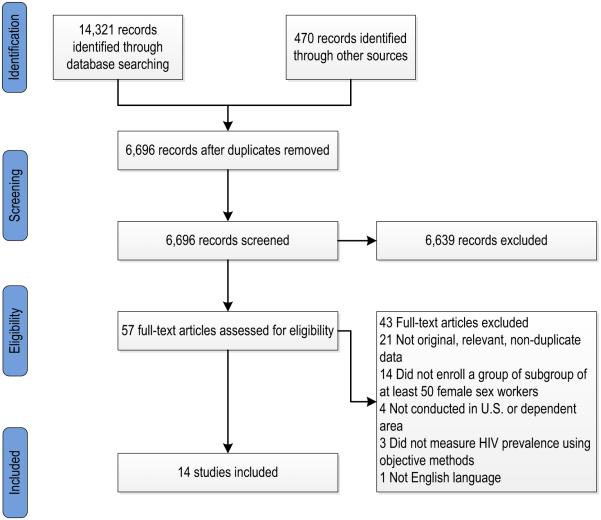

Our searches identified a total of 6696 potentially relevant articles. Of these, 57 met our retrieval criteria and 14 met our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The 14 included studies (Table 1) enrolled a total of n = 4049 adult female sex workers. Most (k = 11) of the 14 included studies were cross-sectional studies aimed at assessing the prevalence of HIV among female sex workers in the United States. Three included studies were not prevalence studies. One was a cohort study of the natural history of HIV [8], and two were longitudinal randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of HIV prevention interventions [18, 33].

Fig. 1.

Study selection process, systematic review of HIV prevalence among female sex workers in the United States

Table 1.

Key characteristics of included studies, systematic review of HIV prevalence among female sex workers in the United States

| Location and reference |

Years of data collection |

HIV prevalence, n/N tested |

Study design and sampling strategy |

Eligibility criteria* | HIV testing method | Demographics | Proportion with any drug use, including injection drugs |

Setting and characteristics of sex work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baltimore [8] |

1988-1989 | 28.4 % (60/ 211) |

Cohort study on the natural history of HIV infection among IDU. Convenience sample; recruitment was done via word-of-mouth within community service organizations. Participants were tested at baseline and periodically thereafter |

Participants were older than 17 years of age, had a history of injecting drugs within past 10 years, and did not have an AIDS-defining illness. Analyses done among baseline data for sub-group of women who exchanged sex for drugs in the past 10 years |

Serum specimens were tested with an IA (Genetic Systems, Seattle, WA) and WB confirmation (DuPont, Wilmington, DE) |

Age: NR, most under 35 years Race: 87 % African American |

100 % with history of injection drug use in past 10 years |

Duration of sex work: NR Condom use with clients and other partners: NR Number of sex partners: In 10 years prior to the interview: 31 % 1–49 partners (169/538), 8 % 50 or more partners (42/538) Setting were sex work occurred: NR Sexual practices traded: NR |

| Baltimore [18] |

2005-2007 | 13.6 % (17/ 125) |

Randomized controlled trial of HIV prevention intervention among high-risk individuals. Convenience sample; participants were recruited through advertisement and community and clinic referrals. Participants were followed over time |

Eligibility included: ages 18-55 years, no injection drug use in the past 6 months, sex with a man in past 6 months, and >1 sexual risk factor (>2 sex partners in past 6 months, STD diagnosis in past 6 months, or high-risk sex partner in past 90 days). Analyses done among baseline data for sub-group of women who reported one or more exchange partner in the past 90 days (N = 128) |

Oral specimens tested with Intercept, OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA |

Median age: 41 years (range 37–7) Race: 98 % African American |

In past 6 months, 77 % crack/cocaine, 51 % heroin; 0 % reported injection drug use in past 6 months |

Duration of sex work: NR Condom use with clients and other partners: NR Number of sex partners: NR Setting were sex work occurred: NR Sexual practices traded: NR |

| California, Bay Area [49] |

1989-1990 | 7.7 % (14/ 182) |

Cross-sectional study to evaluate an AIDS prevention program for sex workers. Convenience sample. Field staff, many of whom were former sex workers, recruited current female sex workers as part of California Prostitutes' Education Project and Association for Women's AIDS Research an Education projects |

Eligibility criteria not reported | Serum specimens tested with unspecified tests |

Mean age: 30 years (SD 7) (range 18-50) Race: 74 % African American, 17 % White, 6 % Hispanic, 4 % other |

66 % with history of crack cocaine use; 39 % with history of injection drug use |

Duration of sex work: NR Condom use with clients: 54 % always, 40 % sometimes, 6 % never (out of 181) Condom use with regular partners: 5 % always, 20 % sometimes, 76 % never (out of 168 with regular partners) Number of sex partners: NR Setting were sex work occurred: 100 % street Sexual practices traded: NR |

| California, Northern [14] |

1996-1998 | 0.3 % (NR) | Cross-sectional study examining differences in health indicators among low income individuals. Single stage cluster population-based study in five counties in northern California in census block groups with median household incomes less than the 10th percentile for each of the five counties. Recruitment was door-to-door |

Women between 18 and 29 who spoke English or Spanish and resided in a low income neighborhood in the target area. Analyses done among sub-group of women who reported ever having exchanged sex (N = 226) |

Serum specimens tested using one of two IA (Organon Technika Corporation, Durham, NC or HIVAb HIV- 1 EIA, Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) and immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) confirmation (Waldheim Pharmazeutika GmbH, Vienna, Austria) with WB (Cambridge Biotech Corporation, Rockville, MD) to resolve any discrepancy. “Some” testing was performed using Orasure (Organon Teknika, Durham NC) during last two study months |

Median age: 26 years (range 18-30) Race: 67 % African American, 11 % Hispanic, 13 % White, 1 % Asian/ Pacific Islander |

In past 6 months, 65 % used marijuana, 37 % cocaine, 14 % speed, 11 % heroin; 20 % with history of injection drug use |

Duration of sex work: NR Condom use with clients and other partners: (at last vaginal sex) 66 % with new partner (95 % CI 49.6 to 81.5), 56% with casual partner (CI 42.3 to 69.4), 25 % with regular partner (CI 18.5-31.9) Median number of lifetime male sexual partners: 25 (range: 10-98) Setting were sex work occurred: NR Sexual practices traded: NR |

| California, San Francisco [44] |

1986-1987 | 9.9 % (7/71) |

Cross-sectional study to assess risk factors for HIV among drug users. Convenience sample; participants were recruited from community- based drug treatment programs |

Analyses done among sub- group of women with history of prostitution |

Serum specimens tested with an unspecified IA and WB confirmation |

NR | 100 % with history of injection drug use |

Duration of sex work: NR Condom use with clients and other partners: NR Number of sex partners: NR Setting were sex work occurred: NR Sexual practices traded: NR |

| Miami [50] | 1987-1990 | 21.7 % (132/607) |

Cross-sectional study to determine prevalence and incidence of HIV in women convicted of prostitution. Convenience sample; participants were tested under a mandatory testing program legislated by Florida statute |

Participants were tested under a mandatory testing program legislated by Florida statute |

Serum specimens tested with an unspecified IA and WB confirmation |

Race: 43 % White, mean age: 28 years; 44 % African American, mean age: 26 years; 10 % Hispanic, mean age: 30 years; 3 % other/NR, mean age NR |

NR | Duration of sex work: NR Condom use with clients and other partners: NR Number of sex partners: NR Setting were sex work occurred: NR Sexual practices traded: NR |

| Miami [33] | 2001-2004 | 20.8 % (156/750) |

Randomized controlled trial of HIV prevention intervention for drug-using female sex workers who solicited clients for exchange sex on targeted prostitution strolls. Participants were recruited through targeted sampling strategies including peer recruitment. 3 month and 6 month follow-up assessments were conducted |

Eligibility included: ages 18-50 years, heroin and/or cocaine use at least three times weekly in the past 30 days and sold sex at least 3 times in last 30 days. Analyses done among baseline data (N = 806) |

Serum specimens tested with unspecified tests |

Mean age: 37 years (SD 8) Race: 63 % African American, 19 % White, 15 % Hispanic, 3 % other |

100 % reported drug use in past 30 days |

Duration of sex work: NR Mean number of unprotected vaginal sex acts in past 30 days: 9.9 (SD 27.9); Mean number of unprotected oral sex acts in past 30 days: 10.9 (SD 35.4) Number of sex partners: NR Setting were sex work occurred: 100 % street Sexual practices traded: NR |

| Multiple [46] |

NR-1987 | 11.7 % (98/835) |

Multi-center cross-sectional study to determine the prevalence of HIV infection among female sex workers. Convenience sample; volunteers recruited through prisons (Los Angeles, Miami); sexually transmitted infection clinics (Colorado Springs, Las Vegas); methadone maintenance clinics (New Jersey); advertisement (Atlanta, San Francisco) |

Eligibility included: age at least 18 years, exchanged sex for money or drugs at least once since 1978 |

Serum specimens tested with an unspecified IA and WB confirmation |

NR | 50 % with history of injection drug use (of 568 interviewed) |

Duration of sex work: NR Condom use (not defined) with regular partners during vaginal sex: 16 %, condom use with clients during vaginal sex: 78 %, 4 % reported condom use with each vaginal exposure during past 5 years Number of sex partners: NR Setting were sex work occurred: NR Sexual practices traded: NR |

| Multiple [43] |

1991-1992 | 25 % (NR) |

Multi-center cross-sectional study among crack users to determine risk factors for HIV infection. Convenience sample; participants were recruited on the street in urban neighborhoods by outreach workers in Miami, San Francisco, and New York |

Eligible participants were ages 18-29 years. Analyses done among sub-group of women who reported exchanging sex for drugs or money in the previous 30 days (N = 337) |

Serum specimens tested with an unspecified IA and WB confirmation |

Ages: 35 % 18-24, 65 % 25-29 Race: 85 % African American, 12 % Hispanic, 3 % other |

100 % used drugs 3 or more days per week in the past 30 days 10 % reported injection drug use within past 30 days |

Duration of sex work: NR Consistent condom use with non-paying partner: 23 % vaginal sex (45/192), 11 % oral sex (12/105), 17 % anal sex (3/18), consistent condom use with paying partner: 46 % vaginal sex (150/329), 31 % oral sex (66/215), 53 % anal sex (9/17) Number of sex partners: NR Setting were sex work occurred: 41 % hotels, 18 % apartments without drugs, 12 % apartments with drugs, 10 % cars, 6 % vacant lots, 3 % crack houses, 3 % hallways Sexual practices traded: 98 % vaginal, 64 % oral, 5 % anal |

| New York City [41] |

1986-1987 | 1.3 % (1/78) |

Cross-sectional study evaluating HIV transmission among high- risk heterosexuals. Current female sex workers affiliated with escort services and massage parlors were recruited through snowball sampling |

Women were included if they had been performing sexual services for pay but had never solicited clients on the street |

Serum specimens tested with IA (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) and WB confirmation (New York Blood Center, New York, NY) |

Mean age: 32 years (range 18-58) Race: 83 % White, 10 % African American, 4 % Asian, 3 % Hispanic |

8 % with history of injection drug use since January 1977 |

Duration of sex work: mean 5.1 years (range: 0.4-18.0 years) Currently (not defined) using condoms (82 %, 64/78), vaginal sex only (47 %, 37/78), oral sex only (0 %, 0/78), both oral and vaginal (32 %, 25/78) Number of sex partners: Mean number in past 12 months 256, median 200 Setting were sex work occurred: 100 % escort service or masseur agencies, never street Sexual practices traded: 100 % vaginal and oral sex |

| New York City [47] |

2010 | 17.0 % (NR) |

Cross-sectional study to monitor HIV risk behaviors, testing history exposure to and use of HIV prevention services and HIV prevalence among groups at high risk for HIV. Heterosexuals at high risk of HIV infection were recruited through respondent-driven sampling |

Eligibility included: ages 18-60 years, low income or low education, New York City residence, opposite-sex vaginal or anal sex in the past 12 months, and English or Spanish comprehension. Analyses done among sub- group of black women who reported exchange sex in the past 12 months (N = 53) |

Serum specimens tested with IA (Genetic Systems HIV-1/ HIV-2 Plus “O” EIA; Bio- Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and WB confirmation (Genetic Systems; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) |

Age: NR; Race: 100 % African American |

NR | Duration of sex work: NR Condom use with clients and other partners: NR Number of sex partners: NR Setting were sex work occurred: NR Sexual practices traded: NR |

| Puerto Rico [16] |

1984 | 16.3 % (13/80) |

Cross-sectional study conducted to evaluate the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in female sex workers. Sampling strategies were not described |

Researchers enrolled sex workers currently engaged in sex work (N = 171). Additional inclusion criteria not reported |

Serum specimens tested with IA (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) and EIA confirmation (ENVACORE; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) |

Mean age: 26 years (range 17–1) Race: NR |

NR | Duration of sex work: NR Condom use with clients and other partners: 14 % always used condoms (8/56), 73 % used condoms some of the time but not always (41/56) Number of sex partners: (each week) 21 % 1-5 partners (12/ 56), 66 % 6-10 partners (37/ 56), 9 % 21-30 partners (5/ 56), 4 % over 40 partners (2/ 56) Setting were sex work occurred: 100 % street or bar with room rental (n = 56) Sexual practices traded: 70 % oral sex, 18 % anal sex (n = 56) |

| Puerto Rico [45] |

1992-1994 | 32.1 % (35/109) |

Cross-sectional study to examine the association between sex workers' psychological status and their HIV serostatus and risk behaviors. Convenience sample; participants were recruited via outreach in brothels and street locations |

Females reported risk behaviors within last 6 months and researchers enrolled current sex workers (N = 127). Additional inclusion criteria not reported |

Serum tested with unspecified tests |

Mean age: 32 years (range 18-60) Race: NR |

47 % with history of injection drug use |

Duration of sex work: NR; Uses condom with sex: 39 % not always (46/118), always 61 % (72/118), uses condom with oral sex: not always 45 % (47/104), always 55 % (57/104) Number of sex partners: NR Setting were sex work occurred: 41 % brothel 59 % street Sexual practices traded: NR |

| Puerto Rico [42] |

1995 | 29.6 % (NR) |

Cross-sectional study to describe female sex workers. Convenience sample; participants were recruited through street outreach from low-income, urban neighborhoods with visible drug trafficking |

Eligibility included: females ages 18-34 years who identified current commercial sex work as a major source of their income. By study design, 50 % had to report current use of heroin or cocaine (N = 311) |

Serum tested with unspecified IA and WB confirmation |

Mean age: 28 years (range 19-39) Race: NR |

39 % with history of crack cocaine, 35 % history of powder cocaine, 61 % history of heroin, 56 % history of speedball 45 % with history of injection drug use |

Years active in sex work: 17 % <1,50 % 1-5, 18 % 6-10, 15 % 11 + Condom use with clients and other partners: NR Number of sex partners: NR Setting were sex work occurred: 68 % street, 8 % bars, 2 % drug-dealing site, 1 % brothel (out of 241) Sexual practices traded: NR |

IDU Injection drug user; IA immunoassay; WB western blot; NR not reported; CI confidence internal; SD standard deviation

Sample size provided if different from total number HIV tested

In nearly all included studies (k = 12), female sex workers were identified for enrollment through convenience sampling (Table 1). Eight studies exclusively enrolled sex workers; the rest assessed sub-populations of sex workers drawn from samples of studies of other populations such as persons who use drugs, high-risk individuals and low income residents of selected neighborhoods. Only two studies were conducted in the last 10 years.

As evidenced by Table 1, reporting on the characteristics of study participants was extremely limited which restricted our ability to generalize the findings of the included studies. Where individual characteristics data were available, it was clear that the characteristics of the female sex workers in the included studies varied widely. For example, the proportion of African American female sex workers in the included studies ranged from 10 to 100% [18, 47]. Most included studies reported little to no information on potential factors associated with HIV prevalence. The duration of employment in sex work was typically not reported, but in the two studies that did report on this, the duration ranged widely from a few months to more than a decade [41, 42]. Sexual practices sold (Table 1) were reported by only three studies, which reported that women sold predominantly vaginal sex, oral sex, or both [16, 41, 43]. In these studies, the percentage of women who sold anal sex was 0 % (among women from escort services and massage parlors) [41], 5 % [43], and 18 % [16]. The reported rate of “always” using condoms ranged from 14 % [16] to 82 % [41]. Only half of the studies reported the setting were sex work occurred (Table 1).

The prevalence of any drug use among enrollees in the included studies was high; however, in some studies, women were selected for study participation specifically because they were drug users [8, 18, 33, 43, 44]. In studies where women were not selected for enrollment in the included study because they were drug users, the proportion of injection drug users ranged from 8 % [41] to 50 % [42, 45, 46].

Quality of Evidence Base

The findings of our quality assessment and the way criteria were evaluated are summarized in Table 2 (items 1 through 10). As noted above, most of the included studies were designed to measure the prevalence of HIV among female sex workers in the various cities throughout the United States. In the three longitudinal studies we used the reported prevalence among female sex workers at baseline. Of most importance to the quality of the studies included in this systematic review is the size of the study, its generalizability and the confidence one has in the measurement of key outcomes such as HIV prevalence.

Table 2.

Assessment of the evidence base using Joanna Briggs Institute Prevalence Critical Appraisal Tool, systematic review of HIV prevalence among female sex workers in the United States

| Item | Criteria | Yes | No | Unclear | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Was the sample representative of the target population? |

0 | 0 | 14 | While all participants were female sex workers in the United States, the degree to which their demographic and HIV risk behaviors are representative is unknown due to the lack of information characterizing this hidden population |

| 2 | Were study participants recruited in an appropriate way? |

2 | 12 | 0 | Since female sex workers are a hidden population, probability samples are costly and logistically challenging. Respondent driven sampling and venue-based sampling are widely used sampling methods for this population. Two studies conducted probability sampling. All other studies used convenience sampling |

| 3 | Was the sample size adequate? | 3 | 11 | 0 | No studies described the process to estimate sample size. We estimated that studies needed a sample size of 384 to estimate a prevalence of 10 % (95 % CI 7–13 %). Only three studies satisfied this criterion |

| 4 | Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? |

5 | 9 | 0 | To satisfy this criterion, we required the study to report the following information about the population: (1) demographics (race and age), (2)selected HIV risk factors (injection drug use; condom use) and (3)setting (place or venue were sex work occurred). Only five studies reported all criteria. Only 10/14 reported injection drug use. We intended to use these factors as potential covariates in meta- regression; while the lack of reporting does not influence the overall prevalence per se, it impacts our ability to understand risk factors associated with HIV and whether prevalence varies based on characteristics and to what degree |

| 5 | Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample? |

8 | 2 | 4 | To satisfy this criterion, we required that more than 90 % of those included in the sample completed an HIV test. Eight of the 14 studies reported testing more than 90 % of participants |

| 6 | Were objective, standard criteria used for the measurement of the condition? |

10 | 1 | 3 | To satisfy this criterion, HIV-positivity had to be determined by an antibody screening test followed by a confirmatory test. Ten studies fulfilled this criteria, one conducted only one screening test and three did not report the testing algorithm used |

| 7 | Was the condition measured reliably? | 10 | 1 | 3 | Ten studies used an adequate HIV testing strategy with an antibody- based screening test followed by confirmation. Three did not specify the tests used. One study conducted only a screening test using oral fluid without a confirmatory test. The oral test currently commercially available has a sensitivity of 91.7 % |

| 8 | Was there appropriate statistical analysis? | 13 | 1 | 0 | The primary objective of this review was to determine prevalence and then use meta-regression and sub-group analyses to explore differences among studies and generate adjusted estimates as appropriate. For convenience samples we only required that studies report the number of participants with a positive HIV test and the total number of individuals in the sample. For probability samples we required for the studies to conduct weighted analyses. Of the two probability-sampling studies, only one conducted weighted analysis |

| 9 | Are all important confounding factors/subgroups/differences identified and accounted for? |

6 | 8 | 0 | To meet this criterion, we required for studies to report HIV prevalence at least by one important sub-group including: race, setting were sex work occurred, injection drug use or number of partners. Four studies reported HIV prevalence by injection drug use, one by number of partners and one by race |

| 10 | Were subpopulations identified using objective criteria? |

12 | 2 | 0 | Sub-group membership was identified based on self-reports that suffer from social desirability bias and recall bias. However, in practice there is no other way to collect such behavioral data than by self-report |

Representativeness, Recruitment, and Sample Size

While all participants included in the evidence base were female sex workers, the degree to which their demographics and HIV risk behaviors are representative of female sex workers in the United States is unclear. This lack of clarity is due to limited reporting of basic information that describes the characteristics of enrollees as well as lack of information that characterizes the underlying population. This situation is further exacerbated by the age of the included studies (only two of studies were conducted in the last 10 years), and the limited geographic coverage of the included studies.

Only two of the studies included in the present evidence base used probabilistic or pseudo-probabilistic sampling methods (cluster sampling [14] and respondent driven sampling [RDS] [47]). The sampling methods used are described for each study in Table 1 and primarily included convenience samples. Individuals recruited in this manner may not be representative of the population of female sex workers in the participating cities.

No studies described the process to estimate sample size. We calculated the sample size required to provide a reasonable estimate of HIV prevalence. Since 11 of the 14 studies in this review reported an HIV prevalence 10 % or greater, we assumed an HIV prevalence among female sex workers in the United States of 10 % [4]. We used the formula n = Z2P(1-P)/d2, where Z is the Z statistic for a level of confidence (Z = 1.96), P is the estimated prevalence (P = 0.10) and d is the precision (d = 0.003) [34]. A total of n = 384 participants would be needed to determine an HIV prevalence of 10 % with a margin of error of 3 % (95 % CI 7–13 %). Only three of the 14 studies had a sample size of 384 or greater.

Description of Study Subjects, Data Coverage and Measurement

Most studies did not report key variables such as demographics, HIV risk factors (i.e., injection drug use; condom use) and setting were sex work occurred (i.e., street vs. establishment-based, city/location). Only five studies reported all the variables listed above. Eleven studies reported injection drug use.

Sufficient coverage of the identified population was defined as conducting HIV testing on at least 90 % of participants [48]. A total of eight studies met this criterion, two did not meet it and data on percent tested was not reported for four.

All included studies conducted laboratory testing to diagnose HIV infection. Most studies (k = 10) conducted HIV testing with an antibody-based screening test and followed with a confirmatory test. Three studies did not specify the testing strategy and one conducted testing with an oral fluid test without confirmation. Oral tests are known to have low sensitivity compared to blood based tests.

Appropriate Statistical Analysis and Confounding Factors

The primary objective of this review was to determine prevalence and then use meta-regression and sub-group analyses to explore differences among studies and generate adjusted estimates as appropriate. For statistical analyses of convenience samples we only required that studies report the number of participants with a positive HIV test and the total number of individuals in the sample. For probability samples we required for the studies to conduct weighted analyses. Of the two probability-sampling studies, only one conducted weighted analysis.

Several studies (k = 11) identified important sub-populations such as female sex workers who inject drugs and half reported the setting where sex work occurred (k = 7). A total of 6 reported HIV prevalence by sub-group. Although membership in these sub-populations was based on self-reported data that suffer from social desirability bias and recall bias, self-report is the standard to collect behavioral information.

Incidence and Prevalence of HIV

The incidence of HIV among female sex workers in the United States was reported by only one dated study. Among 264 women, the study reported that incidence increased from 12 per 100 person-years in 1987–1988 to 19 per 100 person-years in 1991 [48].

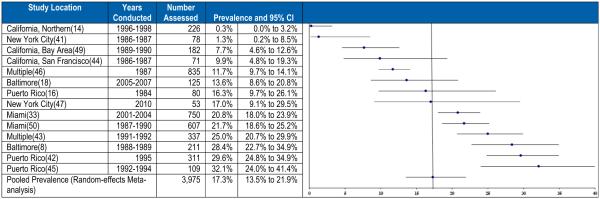

The prevalence of HIV among female sex workers in the United States was reported by all 14 included studies. Reported prevalence ranged from a low of 0.3 % to a high of 32.1%. The pooled prevalence was 17.3% (95 % CI 13.5–21.9 %). The prevalence estimates obtained from the 14 included studies and the resulting pooled prevalence are shown in Fig. 2. This figure is ordered from the study with the lowest (top of figure) to the highest prevalence to emphasize the extent of the variation in reported prevalence. Heterogeneity testing confirmed that the substantial differences in HIV prevalence observed among the included studies was greater than would be expected by chance alone (I2 = 0.89, Q = 123, p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of HIV and meta-analysis among female sex workers in the United States

Exploration of the observed heterogeneity in prevalence estimates observed across the 14 included studies was hampered by poor reporting which limited our ability to explore associations between potentially important covariates (Table 1). Indeed, reporting of the characteristics of the included women and details of the sex practices they employed was so sparse that meta-regression was only possible for one covariate in only a subset of studies: the proportion of female sex workers with a history of injection drug use [8, 14, 41, 42, 44–46, 49]. Three additional studies reported injection drug use only in the last 30 days [33, 50] or 6 months [18] and were not included in this analysis. While this meta-regression did find an association between injection drug use and HIV prevalence among female sex workers included in the analysis (slope = 0.024, 95 % CI −0.003 to 0.05), this association was not statistically significant (p = 0.08).

Further analyses aimed at examining the association between year when the study was conducted and HIV prevalence found no evidence of an association between HIV prevalence and data collection year or year of publication. The HIV prevalence estimate was not statistically significantly different between the two studies that collected data in the last 10 years (15.0 % [95 % CI 7.5–27.8 %]) and those that collected data earlier (17.5 % [95 % CI 13.5–22.3 %).

An influence analysis (in which one study was removed from the analysis at a time) suggests that no single study was particularly influential in the overall summary estimate, which suggests that the studies with very high or very low HIV prevalence did not skew the overall finding.

Discussion

Although female sex workers have been historically identified as a group at high risk for HIV infection, few studies have been conducted to document the burden of disease and associated behaviors among this population in the United States. Our systematic review included only one study that reported on the incidence of HIV among female sex workers in the United States while all 14 reported on the prevalence of HIV. Almost all of the studies were carried out in the early years of the HIV epidemic with only two studies being conducted within the last 10 years. The value of the included studies was further limited by the utilization of convenience sampling methods, limited reporting of potentially important demographic, geographic and sexual risk behavior information, and limited geographic coverage across the United States.

Prevalence estimates varied widely, from 0.3 % in a household based study in Northern California [14] to 32.1 % in a study among women whose primary income was from commercial sex work, half of whom used heroin or cocaine [42]. There were only two studies involving multiple large cities; however, both were conducted more than 20 years ago [43, 46]. The available data are insufficient to provide an accurate picture of the HIV burden among female sex workers in the United States. A rigorous assessment of HIV infection, risk behaviors and gaps in testing, prevention and treatment services is needed in order to guide urgently needed services for this population.

The pooled HIV prevalence among female sex workers in the United States was 17.3 % (95 % CI 13.5–21.9 %), this figure is likely an overestimate, since it is higher than pooled prevalence estimates previously reported for female sex workers in South Asia (5.1 %, 95 % CI 3.2–7.4 %, I2 = .992), Latin America and the Caribbean (4.4 %, 95 % CI 3.0–5.9 %, I2 = .954), and Western Europe (4.0 %, 95 % CI2.1–6.6 %, I2 = 0.88) [4]. Significant heterogeneity across the estimates reported by the studies included in our systematic review, however, implies that no single estimate adequately summarizes the prevalence of HIV among female sex workers in the United States. Attempts to determine whether the observed differences across studies in prevalence might be explained by between-study differences in participant demographics, geography, or HIV risk behavior were limited by poor reporting. Previous systematic reviews in other regions of the world have also reported high heterogeneity [4].

One single variable meta-regression was possible. This meta-regression examined the relationship between prevalence and injection drug use and was based on data collected from a subgroup of studies. While some evidence of an association between injection drug use and the prevalence of HIV was observed, this association was not statistically significant. In view of the high prevalence of injection drug use among female sex workers, further characterization of the relationship between HIV prevalence and injection drug use in this population is needed.

As noted above, this study has several limitations. The included studies cover a period of 30 years. While the long time span may have limited the ability to assess more recent HIV prevalence among sex workers, the meta-regression analyses found no association between HIV prevalence and year of data collection. We chose to include all studies available irrespective of year of data collection in order to document how little information is available in the United States. The limited number of studies did not allow us to further evaluate geographic variation. Our results have limited generalizability since only a few cities were included, female sex workers were mainly recruited from urban settings and most studies were convenience samples. We could not explore the role of factors such as the context where sex work was practiced since sufficient data were not available to warrant meta-regression for variables other than injection drug use and year of data collection. To account for this difference, a random-effects model was used for the meta-analysis. All but two studies used convenience samples.

In summary, the available data suggest that HIV prevalence among sex workers in the United States is high. While not conclusive, the data also suggest that the prevalence of HIV among sex workers who are injection drug users may be even higher as has been reported by other studies [20]. An examination of the impact of a plethora of other potential risk factors for HIV among sex workers in the United States also needs to be performed. Gaining a greater understanding of the prevalence of HIV among sex workers in the United States will inform those charged with public health prevention activities to better address the HIV burden in this population and better characterize the synergies with risk from injection drug use or non-injection drug use. Many modern tools and strategies exist to prevent HIV infection and transmission associated with sex work, such as condoms and new, sterile needles as well as biomedical prevention, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent infection and highly active antiretroviral therapy to prevent transmission.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Melissa Cribbin, MPH, for contributions to protocol and search strategy development. We want to express our gratitude to Amy Lansky and Nicole Crepaz for their review of the manuscript.

Funding Funding was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

These included databases from the following organizations: World Health Organization; Population Council; Family Health International; John Snow International; Engender Health; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Kaiser Family Foundation; Alan Guttmacher Institute; AIDS Action Committee.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.CDC Diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2011. HIV Surveillance Report. 2013;23:84. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/2011/surveillance_report_vol_23.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC . Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2014. Atlanta, GA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker MR, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):538–49. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyrer C, Crago AL, Bekker LG, Butler J, Shannon K, Kerrigan D, et al. An action agenda for HIV and sex workers. Lancet. 2015;385(9964):287–301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60933-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, Duff P, Mwangi P, Rusakova M, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. Lancet. 2015;385(9962):55–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60931-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekker LG, Johnson L, Cowan F, Overs C, Besada D, Hillier S, et al. Combination HIV prevention for female sex workers: what is the evidence. Lancet. 2015;385(9962):72–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60974-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNAIDS . In: AIDSInfo Database. UNAIDS, editor. UNAIDS; Geneva: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Astemborski J, Vlahov D, Warren D, Solomon L, Nelson KE. The trading of sex for drugs or money and HIV seropositivity among female intravenous drug users. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(3):382–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.382. Epub 1994/03/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witte SS, el-Bassel N, Wada T, Gray O, Wallace J. Acceptability of female condom use among women exchanging street sex in New York City. Int J STD AIDS. 1999;10(3):162–8. doi: 10.1258/0956462991913826. Epub 1999/05/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.el-Bassel N, Schilling RF, Irwin KL, Faruque S, Gilbert L, Von Bargen J, et al. Sex trading and psychological distress among women recruited from the streets of Harlem. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(1):66–70. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.1.66. Epub 1997/01/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inciardi JA, Surratt HL. Drug use, street crime, and sex-trading among cocaine-dependent women: implications for public health and criminal justice policy. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2001;33(4):379–89. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2001.10399923. Epub 2002/02/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Weaver JC. The effect of serostatus on HIV risk behaviour change among women sex workers in Miami. Florida AIDS Care. 2005;17(Suppl 1):S88–101. doi: 10.1080/09540120500121011. Epub 2005/08/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonard T, Sacks JJ, Franks AL, Sikes RK. The prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, and syphilis among female prostitutes in Atlanta. J Med Assoc Georgia. 1988;77(3):162–4. 7. Epub 1988/03/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohan DL, Kim A, Ruiz J, Morrow S, Reardon J, Lynch M, et al. Health indicators among low income women who report a history of sex work: the population based Northern California Young Women’s Survey. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(5):428–33. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rolfs RT, Goldberg M, Sharrar RG. Risk factors for syphilis: cocaine use and prostitution. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(7):853–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.7.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraiselburd EN, Gadea C, Torres-bauza LJ. Interactions of HIV and STDs in a group of female prostitutes. Arch AIDS Res. 1989;3(1–3):149–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC . Recommendations of the Advisory Committee for HIV and STD prevention. RR-12. Vol. 47. MMWR Recommendations and reports: Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports/Centers for Disease Control; 1998. HIV prevention through early detection and treatment of other sexually transmitted diseases–United States; pp. 1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudolph AE, Linton S, Dyer TP, Latkin C. Individual, network, and neighborhood correlates of exchange sex among female non-injection drug users in Baltimore, MD (2005–2007) AIDS Behav. 2013;17(2):598–611. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0305-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaddiparti K, Bogetto J, Callahan C, Abdallah AB, Spitznagel EL, Cottler LB. The effects of childhood trauma on sex trading in substance using women. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35(4):451–9. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rusakova M, Rakhmetova A, Strathdee SA. Why are sex workers who use substances at risk for HIV. Lancet. 2015;385(9964):211–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Surratt HL, Inciardi JA. HIV risk, seropositivity and predictors of infection among homeless and non-homeless women sex workers in Miami, Florida. USA AIDS Care. 2004;16(5):594–604. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001716397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohan D, Lutnick A, Davidson P, Cloniger C, Herlyn A, Breyer J, et al. Sex worker health: San Francisco style. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(5):418–22. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.020628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aidala A, Cross JE, Stall R, Harre D, Sumartojo E. Housing status and HIV risk behaviors: implications for prevention and policy. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(3):251–65. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duff P, Deering K, Gibson K, Tyndall M, Shannon K. Homelessness among a cohort of women in street-based sex work: the need for safer environment interventions. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:643. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurtz SP, Surratt HL, Kiley MC, Inciardi JA. Barriers to health and social services for street-based sex workers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(2):345–61. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.UNAIDS . UNAIDS Guidance Note on HIV and Sex Work. Geneva, Switzerland: 2012 Contract No.: UNAIDS/09.09E/JC1696E. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferguson AG, Morris CN. Mapping transactional sex on the Northern Corridor highway in Kenya. Health Place. 2007;13(2):504–19. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The White House . President’s interagency task force to monitor and combat trafficking in persons. The White House; Washington DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beyrer C, Sullivan P, Sanchez J, Baral SD, Collins C, Wirtz AL, et al. The increase in global HIV epidemics in MSM. Aids. 2013;27(17):2665–78. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000432449.30239.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baral SD, Poteat T, Stromdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):214–22. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eden J, Levit L, Berg A, Morton S, editors. Finding what works in health care: standards for systematic reviews. The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ Clin Res. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. Epub 2009/07/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Surratt HL, Inciardi JA. An effective HIV risk-reduction protocol for drug-using female sex workers. J Prev Interv Community. 2010;38(2):118–31. doi: 10.1080/10852351003640732. Epub 2010/04/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(3):123–8. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71. Epub 2014/09/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raudenbush SJ. Analyzing Effect Sizes: Random-Effects Models. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, editors. The handbook fo research synthesis and meta-analysis. 2nd The Russell Sage Foundation; United States of America: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. Epub 2002/07/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shadish WR, Haddock CK. Combining Estimates of Effect Sizes. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, editors. The Handbook or Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. 2nd Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2009. pp. 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Wiley Ltd.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ, Reston JT, Turkelson CM. A system for rating the stability and strength of medical evidence. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-52. Epub 2006/10/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lau J, Schmid CH, Chalmers TC. Cumulative meta-analysis of clinical trials builds evidence for exemplary medical care. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1995;48(1):45–57. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00106-z. discussion 9-60. Epub 1995/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seidlin M, Krasinski K, Bebenroth D, Itri V, Paolino AM, Valentine F. Prevalence of HIV infection in New York call girls. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1988;1(2):150–4. Epub 1988/01/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hansen H, Lopez-Iftikhar MM, Alegria M. The economy of risk and respect: accounts by Puerto Rican sex workers of HIV risk taking. J Sex Res. 2002;39(4):292–301. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552153. Epub 2003/01/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones DL, Irwin KL, Inciardi J, Bowser B, Schilling R, Word C, et al. The Multicenter Crack Cocaine and HIV Infection Study Team The high-risk sexual practices of crack-smoking sex workers recruited from the streets of three American cities. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25(4):187–93. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199804000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiasson RE, Bacchetti P, Osmond D, Brodie B, Sande MA, Moss AR. Cocaine Use and HIV Infection in Intravenous Drug Users in San Francisco. JAMA. 1989;261(4):561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alegria M, Vera M, Freeman DH, Jr, Robles R, Santos MC, Rivera CL. HIV infection, risk behaviors, and depressive symptoms among Puerto Rican sex workers. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(12):2000–2. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.12.2000. Epub 1994/12/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.CDC Leads from the MMWR. Antibody to human immunodeficiency virus in female prostitutes. JAMA. 1987;257(15):2011–3. Epub 1987/04/17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reilly KH, Neaigus A, Jenness SM, Hagan H, Wendel T, Gelpi-Acosta C. High HIV prevalence among low-income, Black women in New York City with self-reported HIV negative and unknown status. Journal of women’s health (2002) 2013;22(9):745–54. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4341. Epub 2013/08/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Finlayson TJ, Le B, Smith A, Bowles K, Cribbin M, Miles I, et al. HIV risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among men who have sex with men—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 21 U.S. cities, United States, 2008. Morbidity and mortality weekly report Surveillance summaries. 2011;60(14):1–34. Epub 2011/10/28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dorfman LE, Derish PA, Cohen JB. Hey girlfriend: an evaluation of AIDS prevention among women in the sex industry. Health Educ Q. 1992;19(1):25–40. doi: 10.1177/109019819201900103. Epub 1992/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Onorato IM, Klaskala W, Morgan WM, Withum D. Prevalence, incidence, and risks for HIV-1 infection in female sex workers in Miami, Florida. J Acquir Immune defic Syndr Human Retrovir Off Publ Int Retrovir Assoc. 1995;9(4):395–400. Epub 1995/08/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]