Abstract

Background:

Ignoring reproductive health services during natural disasters leads to some negative consequences such as reduced access to contraceptive methods, sexual disorders, and pregnancy complications. Despite previous researches, there is still more need for research on this area of health. This study attempts to identify the indicators of reproductive health in the women affected by the East Azarbaijan earthquake on August 2012.

Materials and Methods:

In this descriptive study, reproductive health information pertaining to the years before, during, and after the earthquake were collected and compared in the health centers of the three affected cities including Ahar, Heriss, and Varzaghan as well as the health and forensics centers of the East Azarbaijan province in Iran by census method.

Results:

Findings indicated a decrease in live birth rate, general marriage fertility rate, stillbirth rate, contraceptive methods coverage, and prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases during and after the earthquake. Moreover, important indicators such as neonatal mortality rate and percentage of infants screened for breast milk, decreased during the disaster year in comparison with the years before and after. Other indicators such as preconception care, pregnancy first visit, rate of caesarian delivery, and under 1-year formula milk-fed infants’ percentages increased during the year of disaster in comparison with the years before and after.

Conclusions:

During the earthquake, some indicators of reproductive health have been reported to decrease whereas some others have gone through negative changes. Despite the partly favorable status of services, decision-makers and health service providers should pay more attention to the needs of women during disasters.

Key words: Disasters, earthquakes, Iran, reproductive health, women

INTRODUCTION

There has been a significant increase in the frequency and severity of natural disasters during the past two decades.[1] Iran is a disaster-prone country, being the fourth and sixth disaster-prone country in Asia and in the world, respectively.[2,3] Earthquake, drought, and flood are among the most common natural disasters occurring in Iran.[4] Natural disasters increase the utilization of health resources by people that lasts longer than disaster time.[2,3] Although all people are potentially affected by natural disasters, for various reasons, women and especially pregnant women are among the groups who are exposed to greater risk.[5] Natural disasters can impose negative impacts, through various mechanisms, on women's reproductive health and the health status of their family members.[6] Disasters can also lead to short, medium, and long-term health problems.[7]

Provision of basic reproductive health care services is essential during natural disasters and can save mothers and their children's life. However, despite the importance of sticking to reproductive health principles during natural disasters, this area has not been addressed adequately in recent years.[8] Ignoring these services during natural disasters leads to many negative consequences such as maternal and infant mortality, stillbirth, unwanted pregnancy, unsafe abortion, and increased sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), especially AIDS.[9] Few studies have been conducted on reproductive health care needs during natural disasters. These studies indicated that early pregnancy loss, preterm labor, stillbirth, child-birth related complications,[10,11] menstrual problems,[10,12] increased sexual violence,[9,13,14] and decreased sexual satisfaction[10] are among the severe impacts of natural disasters on reproductive health. Despite all these findings and facts, many affected women suffer from inadequate reproductive health services.[12]

Although little information is available on the impact of natural disasters on women's reproductive health, a need for more information on this issue is felt.[15] Researchers believed that the presence of some indicators such as accessible prenatal care, accessible contraceptive methods, and breastfeeding in affected areas can help health care professionals in identifying and fulfilling reproductive health needs of women.[13] These enable health care professionals to decrease the impacts of natural disasters through some basic measures.[8]

East Azarbaijan is one of the most disaster-prone provinces of Iran where 10 out of all 41 types of natural disasters occur.[16] Two earthquakes measuring 6.3 and 6.4 on the Richter scale occurred on 12 August, 2012 in Ahar, Heriss, and Varzaghan in this province, located in the northwest of Iran in a mountainous and impassible region, which is 5500 km2 in area. These earthquakes affected approximately 263,693 people, of whom 136,000 were women and 44,265 were of childbearing age. Considering the limited number of researches regarding the impact of natural disasters on women's reproductive health, the researchers decided to conduct the current study to identify the indicators of reproductive health in the women affected by the East Azarbaijan earthquake in August 2012.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The current study with a descriptive, retrospective, and time-series (before-after) design was conducted in information and statistic as well as family units in the health centers of Ahar, Heriss, and Varzaghan cities, disease control unit and forensics office in Tabriz, the capital of the East Azarbaijan Province of Iran in summer 2014.

Secondary data of total 44,265 married women aged between 15 and 49 years in earthquake affected regions in three cities were collected and analyzed from 1 year before and 1 year after the index event of the earthquake in 2012. For data collection, the main reproductive health indicators that were affected by natural disasters were identified through an extensive review of relevant literature,[9,10,11,12,13,17,18,19] and indices present in the health system of the affected region were recognized. Then, a checklist comprising five main parts was designed accordingly. The first part included demographic information regarding reproductive health in affected regions; the second part dealt with live birth indicators including the total number of live births, live birth rate, and general marriage fertility rate; the third part included stillbirth, neonatal and infant mortality rate, low birth weight percentage, and the number of maternal deaths; the fourth part of the checklist dealt with receiving reproductive health services before and during pregnancy and postpartum; the last part examined the status of certain sexual health indicators.

The first researcher (F.B.) referred to the above mentioned centers for collecting information available in the rural and urban Vital Horoscope of the three cities for the years 2011 (before the earthquake) to 2013 (the year after earthquake). Because of the large volume of information, all rural and urban information of three cities were merged and presented under the title “the statistics of the affected regions.” Indicators including live birth rate, general marriage fertility rate, infant mortality rate, neonatal mortality rate, stillbirth rate, low birth weight percentage, percentage of coverage of annual and seasonal contraceptive methods, and the number of maternal deaths caused by pregnancy and childbirth complications were obtained from the information and statistic units of the three cities. In addition, indicators such as percentages of preconception care, pregnancy first visit, full pregnancy care, postnatal care, caesarian delivery, infants screened for breast milk, and under 1-year formula milk-fed infants were also collected from the statistical reports of the family unit of main health center of the three cities. For assessment of information regarding STDs, the statistics available in the disease control center of East Azarbaijan province were studied, and reports of all cases on discharge from urethra in men, nonvesicular genital ulcer, and suspected primary and secondary syphilis were considered as STDs. To assess sexual violence and rape cases, researchers referred to the forensics center of East Azarbaijan province. Unfortunately, only sexual crimes statistics were available in the forensics center, so the number of sexual crimes cases was captured as the only available statistic.

All collected pieces of information were registered on the checklist. To describe the indicators of reproductive health, descriptive statistics including frequency and percentage were used. It should be noted that in this study information pertaining to all affected population was gathered, thus there was no need for inferential statistics for generalizing the findings. In most cases, the exact information regarding respective indicator was not available and this information was calculated by placing raw data related to that indicator in the standard formula.

Ethical considerations

For entering the research setting, the research design was approved by the Regional Ethic Committee at the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. For accessing relevant data, permission for data collection was obtained from the health deputy of the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and the main centers of Ahar, Heriss, and Varzaghan cities. All the information and statistics of women affected by earthquake was gathered anonymously and without identifying determinant characteristics of the study population.

RESULTS

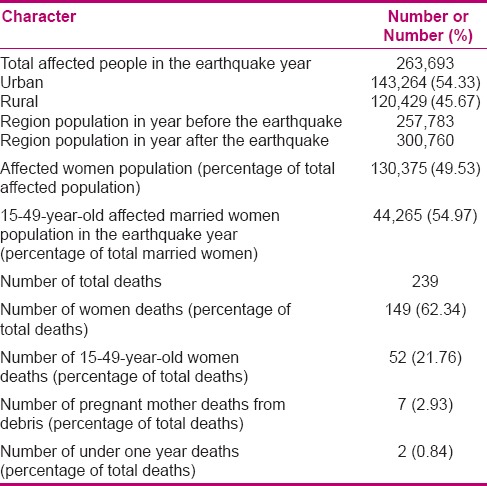

Some demographic characteristics pertaining to the affected regions are reported in Table 1. As shown in this table, around 260,000 people were affected by this earthquake, and 50% of them were women. Furthermore, 62% mortality was reported in women caused by the earthquake.

Table 1.

Demographic characters of affected population in the East Azarbaijan earthquake

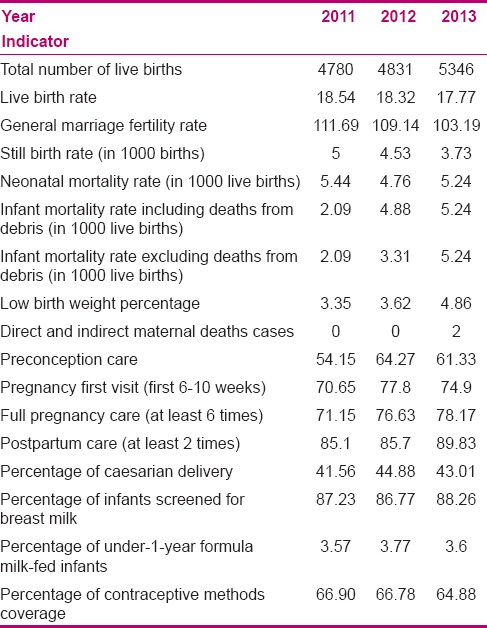

Live birth rate of the years before, during, and after the earthquake are presented in Table 2. As shown in this table, live birth and general marriage fertility rates, two important indicators reflecting the region's fertility status, showed a decreasing trend.

Table 2.

Reproductive health indicators in women affected by the East Azarbaijan earthquake in the years before, during, and after disaster (number, rate, or percent)

This table presents that the annual rate of stillbirth decreased in the year of disaster and the year after, and indicates that the neonatal death rate in the year of disaster was lower than the rates in the previous and following years. However, infant mortality rate has observed a rising trend in the earthquake year, in comparison with the previous year, while including and excluding infant mortality caused by debris. In addition, low birth weight percentage had an increasing trend in affected regions, which is more noticeable in the year after the earthquake.

Furthermore, the received reproductive health services before and during the pregnancy and after delivery in the years before, during, and after the earthquake have been reported in Table 2. It is evident in this table that preconception care and pregnancy first visit increased in the earthquake year in comparison with the years before and after the earthquake. However, full pregnancy care and postpartum care were increased in the earthquake year and maintained to a large extent in the year after. The table also shows that the consumption of formula milk increased during the earthquake year in comparison with the years before and after. The coverage of contraceptive methods also decreased gradually. Caesarian section rate increased in the earthquake year in comparison with the years before and after.

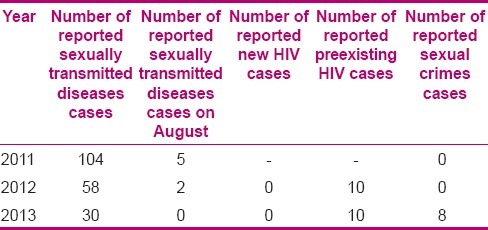

Table 3 presents the sexual health indicators in the years before, during, and after the earthquake. A review of the reported STDs indicates a dramatic decrease in this category in the affected regions. Although an AIDS reporting system did not exist in the year before the earthquake in the health system of the region, the review of this indicator in the earthquake year and the year after shows no changes. Moreover, no sexual crimes were reported in the year of earthquake and the year before, however, eight cases were registered in the year after.

Table 3.

Sexual health indicators in the years, before, during, and after the earthquake

DISCUSSION

An extensive review of relevant literature indicates insufficient knowledge regarding the effects of natural disasters on women's reproductive health indicators. Thus, this research is one of the first studies that investigated changes in reproductive health indicators in women affected by earthquake. In this regards, most important indicators related to reproductive health were reviewed and compared for the years before, during, and after the earthquake. One of the strong points of this study is the investigation of statistics and documents of all affected women. Therefore, no sampling was carried out and differences found here are real and significant and didn’t require any statistical analysis.

One aim of this study was assessment of live birth indicators in the years before, during, and after the earthquake. This assessment shows that, even though total number of live births increased in the year after the earthquake, the two important indicators including live birth rate and general marriage fertility rate decreased in the year of earthquake and the year after and this decrease was greater in the year after the earthquake. It appears that this increase in the total number of live births is due to the increased population of the region because of migration from surrounding regions; this is confirmed by a review of population statistics of the affected region for the year before, during, and after the earthquake. Considering this fact that a large portion of births that occurred in the year after the earthquake might be related to pregnancies conceived after the earthquake and in the spring of the year after, it can be concluded that decreased sexual intercourses among affected couples due to mental-psychological damages, lack of appropriate living environment, and increased abortion rate, pointed out by other studies,[15] can account for this downward trend. This finding has been confirmed by previous studies.[7,10,13,17] For example, Liu et al.[10] reported that 89.4% of affected women declared they had no plans for pregnancy and 67.1% stated that they would terminate their pregnancy in case they get pregnant. Furthermore, He et al.[20] indicated a decrease in pregnancy rate during 12 weeks after the earthquake in the affected province of Sichuan, China. However, these researchers reported an increase in this indicator 12 weeks after the event.[20] As evident in He et al. study, in contrast to the results of the previous studies, pregnancy rate increased three months after the earthquake. Decreased pregnancy rate during the 12 weeks after the earthquake may be due to continued severe aftershocks that causes insecurity in the couples.

Another goal of this study was to investigate stillbirth, neonatal and infant mortality rate, low birth weight percentage, and the number of maternal death in the years before, during, and after the earthquake. In comparison to the years before and after the earthquake, a decrease in neonatal mortality rate was observed in the year of earthquake. This decrease could be associated with quantitative and qualitative improvements in prenatal care. Results of the present study showed an increase in infant mortality rate in the year of earthquake and the year after, which is probably due to unfavorable hygienic condition of temporary accommodations. In comparison to the year before the earthquake, there was an increase in the percentage of low birth weight in the year after the earthquake. Considering the fact that a large portion of these births are related to pregnancies conceived between the earthquake and late spring of the year after (because last menstrual period of these pregnancies were about 10 months ago), it may be concluded that the earthquake is partly accountable for this problem. In addition, mothers’ malnutrition can be another possible reason for this problem. Tong et al.[21] also concluded that low birth weight among women who had delivered after the Red Sea flood disaster had increased. Their result is consistent with our findings. In addition, zero number of maternal mortality in the year of earthquake is an implication of increased attention to providing these women with healthcare services.

Another aim of the present study was the assessment of the level of reproductive health services received before and during pregnancy and after delivery in the years before, during, and after the earthquake. In this regard, the annual coverage percentage of contraceptive methods decreased during the years under the study, and this decrease was greater in the year after the earthquake. Although this indicator was expected to increase due to poor living conditions of the affected people and their unwillingness for pregnancy, poor provision of these methods may account for the non-increase and even decrease in the coverage of contraceptive methods. Furthermore, the results obtained by this study showed that the coverage percentage of prenatal care and the first 6–10 weeks pregnancy care increased in year of earthquake, in comparison to the years before and after. This finding indicates an increase in prenatal care provided by health care personnel during the disaster. These results were confirmed by previous studies.[13]

The results of the study also showed that the percentage of infants screened for breast milk decreased for the year of earthquake in comparison with the years before and after. In addition, the percentage of under-1-year formula milk-fed infants was increased. It should be noted that formula feeding is a source of health problem for both mothers and infants and its preparation requires many resources. On the other hand, breastfeeding is advantageous to infants’ health and also protects mothers against postpartum hemorrhage and short birth intervals. An increase in the consumption of formula milk in affected regions and its concurrency with summer and lack of health facilities such as safe water cause an increase in intestinal diseases for infants.[22]

The results of this study demonstrated an increase in the rate of caesarian section in the year of the earthquake and even the year after. This increase may be due to various reasons such as the increased number of unnecessary caesarian deliveries because of damaged delivery rooms and physicians’ tendency to shorten the pregnancy period and the emergence of obstetric labor complications in pregnant women in the affected regions. Bodalal et al.[23] reported that the proportion of caesarian deliveries increased during conflict situation, and this finding is consistent with the results of present study. Considering the fact that the Iranian Health Ministry attempts, as one of its aims with regard to women's health, to decrease the rate of caesarian delivery and bring it up to the global standards, the statistics of caesarian deliveries during disasters should also be controlled and taken into consideration.

Another aim of this study was investigation of sexual health indicators in the years before, during, and after the earthquake. In this regard, the study results are indicative of decreased number of cases reported on STDs in affected regions; this rate is more evident in the year and month of earthquake. This may be due to the decrease in the referrals of patients to clinics or the decreased number of reported cases or reduction of STD. On the other hand, the results of previous studies indicate an increase in the prevalence of STDs after the occurrence of disasters.[14,24] It should be considered that the statistics of STDs and AIDS are related to governmental centers and many patients and suspects may not have referred for diagnosis and treatment. Thus, it is difficult to draw a final conclusion. With regards to the sexual crimes indicator, despite the fact that no cases were reported in the year of earthquake, the possibility of sexual assaults at the time of disaster cannot be ignored even if the victims did not refer to the forensics centers due to any reasons. On the other hand, some of the cases of sexual crimes reported in the year after the earthquake might belong to the same year of earthquake that have been reported with some delay to the judiciary system.

This study has some limitations. First, there are limited studies regarding reproductive health needs of women during the time of disasters and most of these studies are only narratives and anecdotal. Thus, it is difficult to compare the results of this study with them. Second, there was no control group in this study; it was thus possible for some decreasing or increasing trends to be caused by other factors. Of course, this constraint was mostly resolved through a comparison between the year of earthquake with the years before and after and time series studies do not need a control group. Third, the reporting system and existing statistics in the regional health system, especially those belonging to the year of earthquake, may be inaccurate and imprecise. Fourth, we could collect related data for further years in order to attribute the reproductive health indicators changes to earthquake. Thus, it would be helpful to explore all indicators mentioned in this study through further qualitative studies and interviews with affected women and service providers involved in this disaster.

CONCLUSION

The findings showed that some reproductive health indicators have been maintained and observed properly during the time of disaster; this indicates proper provision of good quality reproductive health services in these aspects. On the other hand, this study showed that, probably, not sufficient attention has been paid to some other aspects of reproductive health such as infant mortality rate, percentages of formula milk-fed infants, caesarian delivery, and low birth weight infants. Thus, greater attention should be paid to these important indicators during disasters. Provision of such services play an important role in decreasing the reproductive-health related problems of vulnerable groups such as women and infants affected by natural disasters. The findings of the present study can be applicable for preparing instructions necessary for providing health care for women and infants during natural disasters.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

This article is part of the PhD dissertation in reproductive health submitted to the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Code 39634). Authors would like to thank all the participants in this research and the health deputy of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and health managers of the earthquake struck towns.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swatzyna RJ, Pillai VK. The effects of disaster on women's reproductive health in developing countries. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:106–13. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n4p106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amiri M, Chaman R, Raei M, Nasrollahpour Shirvani SD, Afkar A. Preparedness of hospital in north of Iran to deal with disasters. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15:519–21. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasraian L. Natural disasters in Iran and blood donation: Bam earthquake experience. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2010;12:316–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbasi M, Salehnia MH. Disaster medical assistance teams after earthquakes in Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15:829–35. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saffarieh H, Farsad H, Azarnoosh Z. Operational guidline of reproductive health teams in disasters. Iranian Red Crescent Society. 2008. [Last accessed on 2012 Aug 02]. p. 9. Available from: http://www.uhtr.ir/./Guidline%20of%20reproductive%20Health%20in%20disast. [in Persian]

- 6.Frakenberg E, Laurito M, Thomas D. The demography of disasters. Prepared for the International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. 2014. Jun, [Last accessed on 2015 Aug 10]. p. 12. Available from: http://ipl.econ.duke.edu/dthomas/./14Jun-EncycDisast. (Area) 3.

- 7.ICM. Health of women and children in disasters. 2011_008. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 13]. p. 1. Available from: http://www.internationalmidwives.org .

- 8.Damerell J, Zutphen T. Public Health Guideline in Emergencies: The Sphere Project. 2nd ed. New York: 2008. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 26]. p. 37. Available from: http://www.nationaltraumacentre.nt.gov.au/./The_Sphere_Pro . [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNFPA. Inter-agency field manual on reproductive health in humanitarian settings. 2010. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 13]. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/./field_ma . [PubMed]

- 10.Liu S, Han J, Xiao D, Ma C, Chen B. A report on the reproductive health of women after the massive 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. [Last accessed on 2015 Aug 10];Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010 108:161–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NDMA and UNFPA. Minimum Initial Service Package for Sexual and Reproductive Health in Disasters. A Course for SRH Coordinates. Facilitator's Manual. 2013. P.v. Available from: http:www.countryoffice.unfpa.org/./UNFPA_Min .

- 12.Alison HP, Jen AS, Tania V, Jeanette C, James W, Richard CC. Menstrual management: A neglected aspect of hygiene interventions. Disaster Prev Manag. 2014;23:437–54. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zotti ME, Williams AM, Wako E. Post-disaster health indicators for pregnant and postpartum women and infants. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1179–88. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1643-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bloem CM, Miller AC. Disasters and women's health: Reflections from the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2013;28:150–4. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X12001677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zotti ME, Williams AM, McKaylee R, Horney J, Hsia J. Post disaster reproductive health outcomes. Matern Child Health J. 2012;17:783–96. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1068-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babai J, Moradian M, Sadeghi F, Ghasemi M. Natural disasters epidemiology in Eastern Azarbaijan. 6th International Congress on Health Emergencies and Disasters, Razi International Conference Center, Iran Medical Science University; Tehran, Iran. 2015. p. 327. [in Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cordero JF. The epidemiology of disasters and adverse reproductive health outcomes: Lessons learned. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;101:131–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101s2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CDC. Health indicators for disaster-affected pregnant and postpartum women and infants. Atlanta, GA: Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Last accessed on 2015 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehe . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atlanta GDORH, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services. Reproductive health assessment toolkit for conflict-affected women. 2007. [Last accessed on 2015 Aug 15]. Available from: http://www.unscn.org/layout/modules/./ToolkitforConflictAffectedWomen.pd .

- 20.He H, Chen F, Zhang Q, Tian D, Qu Z, Zhang X. The Wenchuan earthquake and government policies: Impact on pregnancy rates, complications and outcomes. Arrows Change. 2008;14:4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong VT, Zotti ME, Hsia J. Impact of the Red River catastrophic flood on women giving birth in North Dakota, 1994-2000. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:281–8. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gribble KD, McGrath M, MacLaine A, Lhotska L. Supporting breastfeeding in emergencies: Protecting women's reproductive rights and maternal and infant health. Disasters. 2011;35:720–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodalal Z, Agnaeber K, Nagelkerke N, Stirling B, Temmerman M, Degomme O. Pregnancy outcomes in Benghazi, Libya, before and during the armed conflict in 2011. East Mediterr Health J. 2014;20:175–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wayte K, Zwi AB, Belton S, Martins J, Martins N, Whelan A, et al. Conflict and development: Chalenges in responding to sexual and reproductive health needs in Timor-Leste. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16:83–92. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31355-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]