Abstract

New cancer patients frequently raise concerns about fears, uncertainties, and hopes during oncology interviews. This study sought to understand when and how patients raise their concerns, how doctors responded to these patient-initiated actions, and implications for communication satisfaction. A sub-sampling of video recorded and transcribed encounters was investigated involving 44 new patients and 14 oncologists. Patients completed pre-post self-report measures about fears, uncertainties, and hopes as well as post-evaluations of interview satisfaction. Conversation Analysis (CA) was employed to initially identify pairs of patient-initiated and doctor-responsive actions. A coding scheme was subsequently developed, and two independent coding teams, comprised of two coders each, reliably identified patient-initiated and doctor-responsive social actions. Interactional findings reveal that new cancer patients initiate actions much more frequently than previous research had identified, concerns are usually raised indirectly, and with minimal emotion. Doctors tend to respond to these concerns immediately, but with even less affect, and rarely partner with patients. From pre-post results it was determined that the higher patients’ reported fears, the higher their post-visit fears and lower their satisfaction. Patients with high uncertainty were highly proactive (e.g., asked more questions), yet reported even greater uncertainties following encounters. Hopeful patients also exited interviews with high hopes. Overall, new patients were very satisfied: Oncology interviews significantly decreased patients’ fears and uncertainties, while increasing hopes. Discussion raises key issues for improving communication and managing quality cancer care.

Keywords: patient-provider interactions, patient-initiated actions, cancer communication, fears/uncertainties/hopes

A recent report on the state of cancer in America suggests that by 2030, “the number of new cancer cases in the United States will increase by 45%, and cancer will become the nation’s leading cause of death, largely as a result of the aging of the nation’s population” (Trent, 2014, p. 120). As new cases increase, identifying and addressing patients’ concerns at the outset of cancer journeys is fundamental for quality cancer care. This study reveals that new cancer patients frequently display their fears, uncertainties, and hopes during initial visitations with oncologists. Analysis focuses on 1) when and how new cancer patients raise their concerns, 2) how doctors respond to these patient-initiated actions, and 3) implications of these behaviors for patients’ assessments of communication satisfaction.

Our findings provide strong empirical evidence that “first time/new” cancer patients are surprisingly proactive and involved. These results stand in stark contrast to long-standing and prominent findings about communication during clinical encounters (e.g., Balint, 1957; Byrne & Long, 1976; Frankel, Quill, & McDaniel, 2003; Korsch & Negrete, 1972; Mishler, 1984; Street, Gordon, & Ward et al., 2005; Waitzkin, 1991): “a consistent finding is that patients are relatively communicatively passive: Physicians primarily initiate actions and solicit responses, whereas patients primarily respond to physicians’ initiatives.” (Robinson, 2003, pp. 27–28). For example, doctors have been shown to enact biomedical agendas and control each phase of the medical interview by asking questions, demonstrating medical diagnostic and treatment knowledge, and regulating topics (e.g., see Beach, 2013a,b; Heritage, 2005; Heritage & Maynard, 2006). In response, patients are often described as passive and deferential to the authority of medical experts, “imprisoned within courses of action that are overwhelmingly undertaken at the doctor’s initiative” (Stivers & Heritage, 2001, p.178).

Yet other researchers have systematically examined communication behaviors where patients display more active participation. Activities include patient-initiated question asking, expressing concerns, stating negative feelings, offering opinions about care, and asserting treatment preferences (e.g., see Roter, 2000; Street & Millay, 2001; Street, Krupat, & Bell et al., 2003; Street, Gordan, & Ward et al., 2005; Venetis, Robinson, & Kearney, 2013; in press). Patients also initiate a wide array of other social actions, resources that display how patients orient to medical authority and navigate inherent constraints of the medical interview. Such actions include providing explanations for their problems (Gill, 1998; Gill & Maynard, 2006), extended responses to diagnostic statements (Peräkylä, 2002), making indirect requests (Gill, Halkowski, & Roberts, 2001; Robinson, 2001), providing self-diagnoses (Beach, 2001; Frankel, 2001), resisting or challenging doctors’ assessments (Gill, Pomerantz, & Denvir, 2010), and downplaying risky health behaviors such as excessive drinking (Beach, in press; Halkowski, 2013).

Over the past decade, greater attention has been given to how cancer patients initiate actions when talking with their oncologists, behaviors demonstrating that their concerns merit attention from doctors (Beach, Easter, & Good et al., 2004). For example, proactive actions initiated by lung cancer patients (M=24.39) were twice as frequent as those of lupus (M=11.21) or primary care (M=11.30) patients (Street, Gordon, & Ward et al., 2005). Cancer interviews may be longer than lupus or general practice interviews, permitting more opportunities for patient-initiated actions. However, an alternative explanation is simply that cancer patients have a considerable need to address fears, uncertainties, and hopes.

More recently, Drew (2013) provided evidence that patients resist doctors’ assessments that downplay the potential threat of cancer (e.g., by indirectly questioning explanations provided by doctors). During post-diagnosis visitations, cancer patients also work systematically to initiate actions that justify their wellness, rather than confirm their sickness (Beach, 2013b). And breast cancer patients who assert preferences for surgical treatment also exhibit higher levels of fighting spirit (Venetis, Robinson, & Kearney, 2013). When visitation companions asked questions, anxious preoccupations with cancer decreased. Similarly, when breast cancer patients asserted treatment preferences, and oncologists’ announced some good/hopeful news, post-visit surveys revealed reductions in self-reported hopelessness among patients (Robinson, Hoover, & Venetis et al., 2013).

While oncology interviews have for some time been described as delicate, highly charged, and emotional visitations (Kennifer, Alexander, & Pollak et al., 2009; Pollack, Arnold, & Jeffreys et al., 2007; Roberts, Early, & Lamb, 1990; Surbonne & Zwitter, 1997), the findings presented below suggest that proactive patients work systematically to create hopeful environments, counter fears, and manage the uncertainties associated with cancer threats. The present study examines these possibilities directly by relying on observations anchored in close and repeated examinations of recordings and transcriptions that reveal fears, uncertainties, and hopes as primary social actions prompting further inquiry.

Our research complements a considerable body of literature that offers rich conceptual frameworks for explaining experiences throughout the cancer journey (Beach, 2009; Kristjanson & Ashcroft, 1994). Methodologically, much prior research has relied on self-reported information, anecdotal narratives, or questionnaires assessing perceptions of individuals (e.g., patients, doctors, and nurses) participating in cancer journeys (see Beach, 2009; Beach & Anderson, 2003). For example, Americans have reported fearing cancer more than any other serious medical condition (Nylenna, 1984; Roberts, Early, & Lamb, 1990; Scholmerich, Sedlak, & Hoppe-Seyler, et al, 1987). These fearful societal attitudes are fueled by associating cancer with a host of stigmatizing and at times embarrassing associations: Death and dying, bad news, pain that cannot be managed, negative emotional circumstances, and bodily impacts of treatment (e.g., loss of hair and weight, colostomy bags). Fearful orientations increase as uncertain health challenges arise, including life-threatening possibilities, diagnostic complexities, demanding treatment regimens, ambiguous and dreaded futures (Lutfey, & Maynard, 1998; Maynard & Frankel, 2006). Yet in everyday living, including clinical visitations, good news is preferred over bad news. Hopes for a positive future are elemental resources for ensuring survival, quality of living, and overall well being (Beach, 2014; Bensing, 1991; Groopman, 2006; Maynard, 2003; Robinson, Hoover, & Venetis et al., 2013; Venetis, Robinson, & Kearney, 2013).

The purpose of this study is to examine how or if these conceptions are enacted and managed in actual oncology interviews. Our primary focus in on 1) how patients’ fears, uncertainties, and hopes are raised, directly and indirectly, and 2) integrating pre-and post-visit measures of fears, uncertainties, and hopes with interactional moments during the interview where these actions are displayed and managed. We also assess long-standing concerns with patients’ satisfaction with the interview (e.g, see Inui, Carter, & Kukull, 1982; Roter, Hall, & Katz, 1987; Stiles, Putnam, & Wolf, 1979). By comparing fear, uncertainty, and hope findings with patient’s satisfaction, we extend previous research by linking these key social actions to patients’ reported experiences with clinical encounters. Patients’ question asking, for example, has been found to be negatively associated with interview satisfaction (Venetis, Robinson, & Kearney, in press).

Our secondary focus examines whether and how doctors partner with patients. Historically, considerable attention has also been given to how doctors respond to patient-initiated actions by attending or disattending patients’ concerns (Beach, 2013b). Such actions are often classified using broader categories, such as encouraging or facing cancer together. However, offering and reassuring patients about collaboration is also an essential dimension of partnering (see Baile & Aaron, 2005; Baile, Lenzi, & Judelka et al., 1997; Siminoff & Step, 2011). Extending recent attention given to partnering with patients by the Institute of Medicine (2014), we identify and code moments when doctors informed patients that they are committed to work together as a team as cancer care unfolds. We also examine how emotional patients’ and doctors’ actions might be during oncology interviews (Albrecht, Blanchard, & Ruckdeschel, et al, 1999; Kennifer, Alexander, & Pollak, et al, 2009; Marvel, Epstein, & Flowers et al., 1999; Pollak, Arnold, & Jeffreys, et al, 2007; Suchman, Markakis, & Beckman et al., 1997).

Collaborating Institutions & Research Methods

Findings are reported from a three-year collaboration between a major southwestern university in the U.S. and an NIH-designated comprehensive cancer center. Institutional review boards for both institutions approved the research protocol. Data examined herein are drawn from a sub-sample of more than 28 hours of video recordings, across 44 new-patient interviews meeting with 14 oncologists. The average interview length was 19:24 minutes (range: 3:09–1:13:24). Table 1 displays characteristics of participating doctors; Table 2 displays characteristics of participating patients. All new patients were visiting this cancer center for the first time.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Doctors Participating in Study (N=14)

| Age | Mean=45.5 | Median=45.0 | Range=35–57 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male=8 | 66.7% | |

| Female=4 | 33.3% | ||

| Ethnicity | White=11 | 91.7% | |

| Pacific Islander=1 | 8.3% | ||

| Specialization | Medical oncology=6 | 50.0% | |

| Hematology/oncology=5 | 41.7% | ||

| Gynocological cancer=1 | 8.3% |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients Participating in Study (N=44)

| Age | Mean=58.6 | Median=60.0 | Range: 23–86 years |

| Income | Mean=$79,160 | Median=$72,500 | Range: $10,000-$175,000 |

| Gender | Male=20 | 45.5% | 51.3% |

| Female=19 | 43.2% | 48.7 | |

| Missing=5 | 11.4% | ||

| Marital Status | Currently married=21 | 61.4% | 51.2% |

| Single (never married)=7 | 15.9% | 17.1% | |

| Separated/divorced=6 | 13.6% | 14.6 | |

| Widowed=1 | 2.3% | 2.4% | |

| Missing=3 | 6.8% | ||

| Education | Some college or less=15 | 34.0% | 40.5% |

| 2-year/tech degree=2 | 4.5% | 5.4% | |

| 4-year degree=12 | 27.3% | 32.4% | |

| Grad studies/degree=8 | 18.2% | 21.6% | |

| Missing=7 | 15.9% | ||

| Ethnicity | White=21 | 47.7% | 56.8% |

| Hispanic/Latino=6 | 13.6% | 16.2% | |

| Asian American=3 | 6.8% | 8.1% | |

| African American=2 | 4.5% | 5.4% | |

| Pacific Islanders=1 | 2.3% | 2.7% | |

| Native American=1 | 2.3% | 2.7% | |

| Multiethnic=2 | 4.5% | 5.4% | |

| Missing=7 | 15.9% |

Qualitative and quantitative methods were integrated to assess key relationships between patient/doctor interactions within interviews, and patients’ responses to pre/post measures. Through repeated inductive analyses of video recordings and transcriptions, the qualitative method of conversation analysis (CA) identified primary practices and patterns of new-patient oncology visits (Heritage & Maynard, 2006; Sidnell & Stivers, 2013). From these data sessions, basic units of analysis were identified as pairs of patient-initiated and doctor-responsive actions. Based on these CA findings, coding protocols (see below) were developed to capture key moments and social actions comprising during oncology interviews.

Data Collection Procedures

Patients were informed of the study when they checked in and (if interested) were introduced to researchers in the waiting room. Patients read a written summary of the study, and researchers addressed any patient questions or concerns. Of those initially interested, 85% of patients signed consent forms, agreeing to complete pre-and post-visit questionnaires and permit video recordings of their interviews.

Prior to oncology interviews, patients completed a questionnaire in the waiting room. The instrument included a modified 7-item cancer Fear Index (Facione, 1993), a modified 7-item Uncertainty Index (Mishel, 1997), and a modified 7-item Hope Index (Herth, 1992). Questionnaire items measuring fear, uncertainty, and hope were subjected to confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). All indices were unidimensional, fitting a single factor solution (Table 3).

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for Pre-Visit and Post-Visit Self-Reports of Fear, Uncertainty, and Hope

| Fear | Uncertainty | Hope | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Items | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Pretest | |||

| Mean | 2.53 | 2.56 | 4.52 |

| Standard Deviation | .95 | .91 | .53 |

| Range | 1.00–4.71 | 1.00–4.57 | 3.43–5.00 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | .87 | .88 | .87 |

| Posttest | |||

| Mean | 2.32 | 2.02 | 4.62 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.09 | .79 | .48 |

| Range | 1.00–5.00 | 1.00–3.86 | 3.57–5.00 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | .93 | .89 | .91 |

Indices were constructed and tested for reliability. Cronbach’s alphas were acceptable. The hope index was negatively skewed, indicating high levels of hopefulness before and after the interview. The fear and uncertainty indices were positively skewed, indicating low levels of report fear and uncertainty before and after the interview.

When questionnaires were completed, and an examining room became available, patients were shown to their rooms by nurses. Nurses started and stopped video cameras prior to and at the completion of interviews, and at times were assisted by research team members. However, no researchers were present during interviews. Video recorders were equipped with wide-angle lenses to optimize recordings of communication activities.

Following interviews, patients completed these same measures in the waiting room, as well as an adapted Communication Satisfaction Index – a 6-item subscale assessing socio-emotional reactions to, and satisfaction with, the interview experience (Robinson & Heritage, 2006).

Coding for Patient-Initiated and Doctor-Responsive Actions

Coding protocols were developed to identify how patients raised fears, uncertainties, and hopes, and how doctors responded to these actions. Only verbal actions were coded. Within other patient-provider coding systems (e.g., Roter, 1991; Street & Millay, 2001; Ward, Sundarmurthy, & Lotstein et al., 2003), similar kinds of patients’ actions would be subsumed within more general categories (e.g., “expressed concerns”). The present analysis was tailored to particular types of social actions – interactional displays of fears, uncertainties, and hopes – first identified using conversation analytic data sessions as routinely enacted actions by cancer patients.

Basic units of analysis are pairs of a) patient-initiated fear, uncertainty, and hope actions and b) responses of doctors. If a patient’s initiation extended across multiple turns at talk, each pair of patient/doctor actions was individually coded until the activity in progress was completed.

To identify patient-initiated actions, distinctions were first made between direct and indirect actions. Direct actions initiated by patients include lexical references (e.g., afraid, uncertain, hopefully). Indirect actions were non-lexical, but displayed a primary focus on being fearful, uncertain, or hopeful (e.g., stating a concern, seeking clarification, announcing good news). Coding an action as direct implies only the use of lexical references, not that this action was, for example, more emotional or forceful. Questions were coded as interrogatives, but only coded as a direct action if lexical references were employed (e.g., afraid, uncertain, hopefully; see exemplars of fearful and uncertain indirect questions in Table 4).

Table 4.

Patients’ Direct and Indirect Actions Displaying Fears, Uncertainties, and Hopes (N=1,070)

| Type of Action | Selected Exemplars (and Interview ID#) | Number of Action Types |

Percent of Total |

Inter-rater (Cohen kappa) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear-Direct (lexical/“afraid” →) |

|

(OC 5:5) | 31 | 2.9% | .65 |

| Fear-Indirect (states concern/asks question →) |

|

(OC 4:6) | 355 | 33.2% | |

| Uncertainty-Direct (lexical/”I don’t know” →) |

|

(OC: D1P2:2) | 73 | 6.8% | .94 |

| Uncertainty-Indirect (asks question →) |

|

(OC: D1P4:14) | 351 | 32.8% | |

| Hope-Direct (lexical/”hopefully” →) |

|

(OC1: 17–18) | 30 | 1.0% | .67 |

| Hope-Indirect (announces good news →) |

|

(OC3: 18) | 230 | 21.5% |

Importantly, the examples provided (e.g., “I don’t know” as uncertainty indirect, “That concerns me…So you think it’s increased in size a little bit?” as fear indirect, or “announces good news” as hope indirect) describe only the actions apparent in utterances provided for Table 4. One primary emphasis involved training coders to reliably recognize that patients’ utterances, involving words or phrases such as “I don’t know” or “concerns”, may or may not constitute displays of uncertain or fearful actions. Similarly during other moments, when patients seem to be announcing good news, they may or may not be producing hopeful actions indirectly. For example, when cancer patients are attempting to justify wellness, their actions may be designed to ward off and convince doctors they are not sick. In these cases, patients are not necessarily displaying hope directly or indirectly (Beach, 2013a).

Doctor-Responsive Actions

A range of features were coded in order to understand how doctors responded to patient displays of fear, uncertainty, and hope. The following five actions were selected to better understand what has historically been described as “biomedical” responses to patients (see Beach, 2013b): 1) immediate (proximal) or deferred; 2) particular response addressing co-present patient, or generic response about cancer patients in general; 3) probability statements (e.g., “most patients”, “3 out of 5 patients”); 4) use of percentages (e.g., “75% of all patients”); and 5) relying on biomedical terminology (e.g., “sentinel lymph node biopsy,” “fibrocystic changes throughout”).

Doctors exhibiting partnering behaviors were also coded (e.g., “We’ll work together and figure out what’s best for you;” “We’re going to fight this thing together”).

A basic assessment of whether patients’ and doctors’ actions were communicated with emotion (e.g., see Ong, Visser, & Kruyver et al., 1998; Pollack, Arnold, & Jeffrey et al., 2007) was also implemented using a 3-point scale (0 = hearably unemotional, 1 = minimal emotion, 2 = marked/expressive emotion).

Identifying Utterances, Coding Teams, and Intercoder Reliability

Coding of interactional data proceeded in two stages. First, patient-initiated utterances displaying fears, uncertainties, and hopes were initially identified by a team of three research team members engaged in over 20 hours of conversation analytic data sessions. Consensus among all three analysts was required for an utterance to be included in the study as exemplars of fears, uncertainties, and hopes. Second, each coder and team received 10–12 hours of training prior to coding for direct, indirect, and other features of fear, uncertainty, and hope utterances. Identified utterances were marked within full transcriptions. To insure rigor, two teams of coders (two coders per team) independently double-coded 5 complete interviews (12% of total interviews) to determine inter-coder reliability (Krippendorf, 1980). Across these 5 interviews, a sampling of 171 coding decisions were made of patients’ utterances and doctors’ responses to fear (68/17.6% of total), uncertainty (63/14.9%), and hope (40/15.4%). Third, calculations for Cohen’s kappa resulted in inter-rater reliability coefficients of .65 for Fear, .94 for Uncertainty, and .67 for Hope – all within sufficient ranges as reported in related coding studies (e.g., Street, Gordon, & Ward et al., 2005).

Data Analysis at Two Levels

Data analysis was conducted at two levels. When analyzing data at the interview level (N=44), alpha was set at .10 to reduce Type 2 error. When analyzing data at the patient-initiated/doctor-responsive level of actions occurring within the interview (N =1070), alpha was set at .05. Statistical analyses proceeded in three steps. First, correlations were computed between variables at the patient-initiated/doctor-responsive level (N =1070). Second, the frequency and mean number of paired actions, by type (N =1070), were computed and aggregated at the interview level (N = 44). Third, correlations and other statistical tests were conducted on pre-and post-visit self-reports of fears, uncertainties, and hopes, as well as communication satisfaction. Valid sample size reported for each test indicates whether the analysis was conducted using patient-initiated actions as the unit of analysis, or whether the analysis was conducted at the interview level.

Results

Coding teams identified an average of 24.31 patient-initiated actions per interview (approximately 10 uncertainty, 9 fear, and 6 hope). Thirty-nine of the 44 interviews included at least 2 or more patient-initiated actions. Table 4 displays the distribution of indirect and direct patient-initiated actions. Most patient-initiated actions (87.5%) were indirect. Direct and indirect patent-initiated actions of uncertainty were most frequent (39.6%), followed by direct and indirect fear (36.1%), and direct and indirect hope (22.5%). These findings support the conclusion that first-visit cancer patients appear to be highly proactive.

Patients with higher levels of education generated significantly more patient-initiated actions than did patients will lower levels of education, r (24) = .46, p = .01. The number of patient-initiated actions was not related to income, gender, ethnicity, age, or marriage. No significant differences were discovered between types of cancer and frequency or types of patient-initiated actions.

Summarized below are results regarding how patients’ and doctors’ manage cancer fears, uncertainties, and hopes. Overviews are also provided of doctors’ partnering with patients, displays of emotions, and patients’ satisfaction with oncology interviews.

Cancer Fears

Most patient-initiated actions regarding fear occurred before the physical exam (76.7%). Fear Index scores prior to the visit were highly correlated with Fear Index scores after the visit, r (27) = .94, p < .001. Patients with higher scores on the pre-visit Fear Index were more likely to initiate direct fearful actions during the interview, r (310) = .30, p < .001, and to ask more questions (42/386=11%). However, the majority of fears about cancer were expressed indirectly: Patients directly stated their fears using explicit terms (e.g., fear, afraid, fearful, or scared) in only 31 (8.0%) of 386 fearful actions.

When patients asked fearful questions, doctors were more likely to use generic utterances, r (385) = .26, p < .001, and to use biomedical terms, r (385) = .24 p < .001. In response to patients’ questions focusing on fear, doctors used probabilities or percentages only 1.5% of the time. In about 25% of cases, doctors did respond with statements tailored to the patient’s specific circumstances.

Cancer Uncertainties

Most patient-initiated actions regarding uncertainty occurred before the physical exam (54.5%). Dealing with patient uncertainties challenges both patients and doctors. Patients with higher scores on the pre-visit Uncertainty Index were no more likely to initiate actions about uncertainty than patients with lower scores, r (29) = .04, p = .43. Similar to cancer fears, 82.7% (351/424) of uncertain actions by patients were indirect. Direct uncertain references (e.g., “I’m not certain”, “I don’t know”) were more frequent with uncertainty (73/424=17.2%) than with fears (31/386=8.0%) or hope (30/260=11.5%). Not surprisingly, patients used questions to raise uncertainty (e.g., seeking more information, clarification) more frequently (63/424=14.8%) than did patients using questions to address fear (42/386=11%%) and especially hope (7.8/260=3%).

Doctors addressed patients’ uncertainties 98% (417/424) of the time and did so immediately 97% (413/424) of the time. Patient-specific language was used 32% (137/424) of the time and generic language in only 9% (38/424) of cases. Doctors eschewed the use of probabilities (<1% or 2/424) and percentages (1% or 6/424), but did use biomedical terminology more frequently (29% or 121/424). When uncertainties were expressed directly, however, doctors were less likely to address the patient’s uncertainty, r (424) = −.09, p = .04, and less likely to use either biomedical terminology, r (424) = −.12, p < .01, or generic utterances, r (424) = −.10, p = .02.

The post-visit Uncertainty Index revealed that patients who initiated more actions about uncertainty during the interview were significantly more uncertain after the medical interview, r (27) = .41, p = .03. Doctors tended to be less responsive when patients were uncertain and sought answers directly.

Cancer Hopes

Most patient-initiated actions regarding hope occurred before the physical exam (72.5%). Patients with higher scores on the pre-visit Hope Index initiated more hopeful actions during the interview, r (37) = .32, p < .05. Such hopeful actions were generally indirect (230/260 = 88.5%) rather than explicit (e.g., hope, hopeful, hopefully). However infrequent, when patient-initiated actions about hope were direct (30/260 = 2.8%), such actions were more likely to be posed as questions, r (260) = .24, p < .001.

Doctors addressed hopeful actions immediately 92.7% of the time, but with minimal emotion. Doctors were also more likely to respond with both patient-specific utterances, r (260) = .13, p = .02, and generic utterances, r (260) = .11, p < .05. Similarly, when hopes (either direct or indirect) were posed as a question, doctors were more likely to respond using patient-specific utterances, r (260) = .20, p = .001; generic utterances, r (260) = .13, p = .02; and biomedical terminology, r (260) = .12, p = .03. Overall, 21.5% of doctors’ responses to hopeful issues were tailored to patients’ specific circumstances, while generic responses (e.g., placing a patient in a group or population of similar diagnoses) were rare (2.3%). Doctors utilized biomedical terminology 16.2% of the time when addressing hopes of patients.

Only 3% of hopeful actions (7/260) were posed as questions. When hopeful utterances posed as questions were direct 13% (4/30) and indirect 1% (3/230), the difference is statistically significant (χ2 (1, N=260) = 10.43, p = .001).

Partnering With Patients

Verbal displays of partnering with patients was uncommon, offered in response to only 10.1% of patient-initiated actions. Significantly, doctors were more likely to verbally partner with patients who generated higher numbers of patient-initiated actions, r (39) = .43, p < .01. Regarding fear actions, doctors were more likely verbally partner with patients who asked questions, r (386) = .26, p < .001. If fearful actions (either direct or indirect) were initiated after physical exams, doctors were more likely verbally partner with the patient, r (386) = .19, p < .001, and to display emotion, r (386) = .09, p = .04.

Doctors were much more likely to verbally partner with patients who initiated uncertain actions (15.3%) when compared with fear (7.5%) or hope (5.4%), χ2 (2, N=1070) = 21.99, p < .001. Doctors who did verbally propose partnerships with such patients displayed higher levels of emotion, r (424) = .17, p = .001. And doctors were also somewhat less likely to verbally display partnership with patients after a directly initiated uncertain action, although the relationship does not achieve statistical significance (r (424) = −.06, p = .12).

When asked, hopeful questions from patients prompted significantly more displays of verbal partnering actions by doctors, r (260) = .17, p < .01. If hopeful actions occurred after rather than prior to physical examinations, doctors were considerably more likely to express partnership with patients, r (260) = .16, p < .01.

Displays of Emotions

Table 5 displays the breakdown of the level of emotional displays by patients and doctors. To summarize, patients express minimal or no emotions 98.2% of the time when initiating social actions; in response, doctors express minimal or no emotions 98.5% of the time. When patients reported higher scores on the pre-visit Fear Index, doctors displayed lower overall emotional responses to fearful patient-initiated actions, r (31) = −.31, p = .09.

Table 5.

Displays of Emotions in Patient-Initiated & Doctor-Responsive Actions

| Level of Expressed Emotion | Fear | Uncertainty | Hope | Averages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Doctors | Patients | Doctors | Patients | Doctors | Patients | Doctors | |

|

| ||||||||

| Hearably unemotional | 0.0% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 5.0% | 0.0% | 2.6% |

| Minimum emotion | 96.9% | 96.1% | 98.8% | 97.4% | 98.8% | 94.2% | 98.2% | 95.9% |

| Marked/ expressive emotion | 3.1% | 2.6% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 0.8% | 1.8% | 1.5% |

| Totals | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Minimal emotion was identified across the majority of patients’ uncertainties, though patients displayed significantly higher levels of emotion during direct patient-initiated actions, r (424) = .18, p < .001. When uncertainties were expressed directly, doctors were less likely to display emotions, r (424) = −.11, p = .01. Patients generally expressed hope with minimal emotion, though direct hopeful actions involved higher levels of patient emotion, r (260) = .19, p = .001. When compared to doctors’ displayed emotions, however, patients were significantly more likely to display higher affect when initiating hopeful actions, t (259) = 3.37, p = .001. Hopeful questions by patients elicited doctor-responsive actions that were more emotional, r (260) = .13, p = .04.

Overall Satisfaction With Oncology Interviews

The overall impact of communication in oncology interviews was extremely positive. As summarized in Figure 1, oncology interviews significantly decreased patients’ fears from pre-visit to post-visit, t (26) = −3.55, p < .01, decreased patients’ uncertainty from pre-visit to post-visit, t (22) = −4.09, p < .01, and increased patients’ hope from pre-visit to post-visit, t (31) = 2.09, p < .05.

Figure 1.

Pre-visit and post-visit self-reports of patients’ fears, uncertainties, and hopes

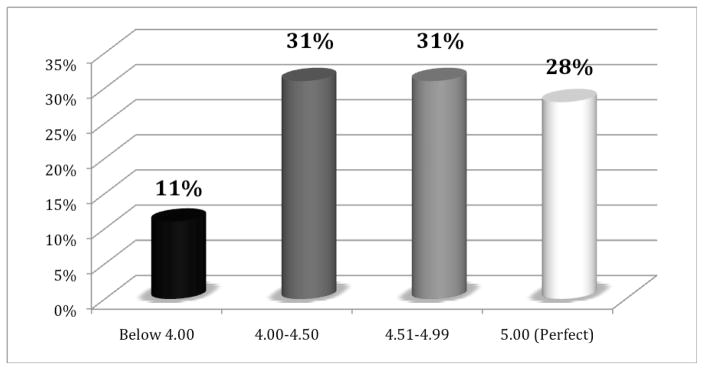

Overall, patients reported high levels of communication satisfaction with interviews. The measure of interview satisfaction ranged from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). Ninety percent of patients reported interview satisfaction scores in the 4.0 – 5.0 range (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Post-visit patient communication satisfaction scores

However, overall patient satisfaction with the interview was negatively related to the number of fearful actions patients raised during the interview, r (31) = −.30, p = .05: The more times patients initiated actions to address their fears, the less satisfaction they reported after the visit.

Communication satisfaction was not directly related to the number of uncertainty actions during the medical interview, r (31) = −.10, p = .60. However, the number of uncertainty actions initiated during the interview was positively correlated with patient reports of uncertainty after the visit, r (27) = .41, p < .05. Patient reports of uncertainty after the visit were negatively correlated with patients’ satisfaction, r (27) = −.52, p < .01.

Similarly, communication satisfaction was not significantly related to the number of hope actions, r (31) = −.09, p = .62. However, satisfaction was positively correlated with patients’ self-reports of hope prior to the interview, r (30) = .50, p < .01, and, even more significantly, after the interview, r (30) = .57, p = .001.

Discussion

When faced with cancer, new patients were found to be highly proactive. Actions were frequently initiated that focused on their fears, uncertainties, and hopes. On average, 24.31 patient-initiated actions were identified per interview. This frequency mirrors findings by Street, Gordon, &Ward et al. (2005), who discovered that lung cancer patients initiated 24.39 actions per visit. Such proactive behaviors are inconsistent with theories of passive deference to medical authority. This is especially true for patients with more formal education. In contrast, Ong, Visser, & Kruyver et al. (1998) reported that cancer patients did not ask more questions or express more concerns than general practice patients. They described first visits as highly informational, doctor-driven encounters. These discrepant findings may be rooted in a fifteen-year (1998 vs. 2014) time span, especially in light of the availability of such resources as online medical information, as well as the utilization of different coding systems utilized. Future research should employ greater specificity when identifying patient-initiated behaviors as particular kinds of social actions.

When collecting data for this study, oncologists informally but repeatedly reported problems with “talkative” patients. While managing interview length is a long-standing communication challenge for healthcare providers, our findings suggest that patient proactivity reflects interactional orientations to cancer that trigger primal concerns about survival and quality of life. In this study, 87% of patient-initiated actions were raised indirectly, providing only cues and clues for oncologists to decipher (see Levinson, Gorawara-bhat, & Lamb, 2000). This challenges doctors to respond to issues that patients may only hint at (Gill, 1998). Recognizing and addressing what patients treat as important raises fundamental challenges and opportunities for refining communication activities in comprehensive cancer centers (Epstein & Street, 2007; Schofield, Butow, & Thompson et al., 2002; Surbonne & Zwitter, 1997; Venetis, Robinson, & Turkiewicz et al., 2009). If healthcare providers can create communication environments that invite and reward patients for being direct, then more time and resources become available to provide quality healthcare through trusting, sustainable relationships between doctors and patients. To do so, doctors must identify and adequately respond to both direct and indirect actions of patients. Brief yet authentic displays of understanding and sensitivity from doctors should not just acknowledge but directly address the fears, uncertainties, and hopes of patients.

Patients that reported high levels of fear before the interview initiated more direct actions. Yet higher levels of these fear-based actions during the interview were negatively correlated with patient satisfaction following the interview. Patients reporting high levels of fear consistently displayed high levels of fear during, and low levels of satisfaction after the visit. Apparently, doctors’ responses to patients’ fearful actions did not reduce post-interview fears. One solution to this problem is to have patients complete a brief questionnaire measuring their fear prior to interviews. Doctors could review self-reported fears before meeting with new patients. When patient fears are high, doctors could be prepared to initiate additional, concerted efforts to encourage patients to express their fears directly. In response, doctors could also help patients manage the altogether normal anxieties inherent to cancer journeys. Realistically, however, patients’ fearful predisposition may persist following interviews, despite concerted efforts of oncologists to respond to those fears during the interview. Coming to grips with these possibilities provides unique opportunities to improve patient-centered cancer care.

Similarly, patients with high hopes before the interview initiated more hopeful actions during the interview, yet these same patients also exited interviews with high hopes. Patients with hopeful reserves tend to remain positive regardless of the valence of cancer news and emerging treatment challenges. This suggests an ability of hopeful patients to access personal resources (e.g., beliefs and faith) while navigating cancer journeys. When hopes are enacted communicatively, and not just experienced individually, doctors are challenged to discern and act appropriately on what patients treat as hopeful news. If doctors can better understand what patients are hoping for—and how patients interactionally attempt to display and achieve those hopeful outcomes—doctors could then tailor and implement more effective communication strategies for specific patients.

Unlike pre-interview self-reports of fears and hopes, patients with high levels of uncertainty prior to their interviews did not initiate significantly more actions to reduce their uncertainty during the interview. Counter-intuitively, however, the number of patient-initiated actions taken to reduce uncertainty during the interview correlated with increased uncertainty after the interview. Most patients (82.8%) initiated indirect (rather than direct) actions to reduce their uncertainties. Doctors responded to such indirect actions immediately (rather than delayed responses), using generic language, biomedical terminology, and low levels of affect. Patient bids to reduce uncertainty within the interview seem to increase uncertainty after the visit. Closer inspections of these moments reveal that direct questions and indirect actions that patients initiate to reduce uncertainties may not receive clear, understandable answers from oncologists and is an important focus for future research efforts. This parallels findings of Venetis, Robinson, and Kearney (2013), who concluded that breast cancer patients regarded the information provided to them by their surgeons as insufficient or inadequate. Our data revealed that the answers that doctors provided were often lengthy. And answers spanned a wide, complex range of biomedical and technical issues (replete with jargon) that patients may find difficult to understand. For future clinical training, doctors might learn to recognize that detailed and complex answers, although meant to reduce uncertainty, may have the opposite impact on patients. Systematic efforts could be made to reduce patients’ uncertainties with shorter, focused descriptions appropriate for “lay” persons. More frequent summaries of key points, and checks of patients’ understandings, could also help to alleviate uncertainty disjunctures between patients and doctors. Despite time constraints, doctors should encourage patients to not just solicit further information and clarification, but expect that doctors will address uncertainties and other patients’ concerns clearly and with sensitivity to patients’ circumstances (Fallowfield & Jenkins, 1999; Ford, Fallowfield, & Lewis, 1995; Maguire, Booth, & Elliot et al., 1996; West & Baile, 2010).

Patients that initiated direct actions (often in the form of questions) altered the interview flow in significant ways. When patients asked hopeful questions directly, doctors responded with higher levels of affect and were more likely to offer partnerships to such patients. When patients directly asked questions about fear, doctors were more likely to provide generic answers, to use biomedical terminology, and to offer partnerships. When patients were direct with their doctors about their uncertainties, doctors responded with delayed answers, used generic language, employed biomedical terminology, and displayed lower levels of affect. Arguably, patients should initiate more direct actions during medical interviews, often in the form of questions. Simultaneously, doctors need to develop tools to measure, review, and assess the relative levels of patient fears, uncertainties, and hopes prior to oncology interviews. Using these diagnostics, doctors can better and more proactively tailor their interactional practices to not just advance biomedical agendas but better accomodate patients’ biopsychosocial needs (Beach & Mandelbaum, 2003).

Oncologists offer partnerships to their patients only 10% of the time. Such partnerships are not promises for “cures”, but display sensitivity and commitment that doctors are willing and able to work together as teams to deal with the fears, uncertainties, and hopes of everyday cancer journeys. In this study, more proactive patients were more likely to be offered partnerships with their doctors. It is also important to encourage cancer patients to inquire about the availability, commitment, and the continuity of care from their doctors.

Our preliminary findings on emotions may contradict societal stereotypes that cancer and cancer care involve frequent and highly emotional events across a wide variety of activities. In this study patients overwhelmingly raised their concerns, and doctors responded, with minimal emotion. A simple 3-point coding scale (hearably unemotional, minimal emotion, marked/expressive emotion) was utilized to categorize levels of displayed emotions. Coders were able to reliably identify and agree upon basic levels of displayed emotional behaviors. This finding confirms previous findings that, despite their possible distress, patients only infrequently display emotions (Pollak et al., 2007; Kennifer et al., 2010). Although doctor’s responses are more frequently immediate than delayed, our findings confirm that they exhibit seemingly stoic orientations to delicate matters regarding good and bad news (Maynard, 2003). Doctors may withhold emotional responses (knowingly or not) to patients’ expressed concerns in order to project a stable, steady, and unafraid persona. So doing optimizes their medical authority and ability to pursue biomedical agendas central to cancer care (Beach, 2013b). It is also possible, and understandable, that doctors may become somewhat desensitized to the emotional concerns of patients as a result of frequent and routine visits with diverse patients facing challenging cancer journeys. Oncologists are clearly engaged in a strategic battle to balance patients’ feelings while also striving to at least maintain the stability, if not promote remission, of patients’ cancer status. In turn, patients may also refrain from expressing emotion at the outset of their cancer journeys, mirroring the stoic demeanor displayed by doctors. Closer attention needs to be given to how emotions are achieved interactionally, as inherently social constructions that transcend isolated individual experiences (see Goodwin & Goodwin, 2000; Peräkylä & Sorjonen, 2012; Roter, Frankel, & Hall et al., 2006; Ruusuvuori, 2013). Understanding the social construction of emotions can help doctors provide affective responses that demonstrate respect for the feelings of their patients, actions that can occur while simultaneously pursuing biomedical solutions to problems.

Prior research has also shown that doctors have problems responding to patient-initiated actions prior to the physical exam (Jones & Beach, 2005; Heritage & Maynard, 2006). Doctors rely on medical histories and physical exams as a basis for providing subsequent and more definitive diagnoses and treatment recommendations. This study revealed, however, that most patient-initiated actions occur prior to the physical exam (716/1070 = 66.9%) – actions that may compete with doctors’ efforts to conduct medical history-taking (Heritage & Maynard, 2006). However, doctors are encouraged to address patients’ concerns, whenever they occur, to demonstrate that they are open and receptive to patient-initiated actions. Doctors’ responses can be minimal, such as acknowledging concerns when patients raise them and reassuring patients that any raised issues will be addressed later in the interview. Such actions can be augmented by insights gleaned from the patient’s medical history and physical exam (Gill, 1998; Gill & Maynard, 2006).

Limitations and Further Research

This study has several limitations. First, only 44 new patient visitations were examined at one comprehensive cancer center. Although a seemingly remarkable total of 1070 identified patient-initiated actions provided ample data for this analysis, a larger sample that includes new and returning patients will provide a stronger basis for generalization. Second, the explicit focus on new visits limits our generalizations to the special circumstances of first visits to oncologists. Future research that includes patient data collected over time, across numerous visitations and phases of cancer journeys, may reveal significant changes in how patients and doctors interactionally manage fears, uncertainties, and hopes. Third, the cancer center where data were collected serves a highly educated patient population with above-average socioeconomic status. Findings in this study suggest that educated patients are more proactive than those with less formal education. A more diverse sample is needed to confirm the impact of education on patient participation, including whether and how the presence of companions (e.g., family members and significant others) influenced patient participation and doctors’ behaviors. Fourth, coding for both emotions and partnering were limited. Researchers should refine coding protocols to protocols capture more complex dimensions of social activities comprising emotional and partnering displays. It was also clear that, while inter-rater reliability coefficients were all in acceptable ranges (fear=.65, uncertainty=.94, hope=.67), coders had more difficulties identifying and agreeing on fears and hopes than uncertainties. Less prior research has been done on the interactional features of fears and hopes, important social actions requiring more systematic attention. Fifth, data coding in this study measured whether or not doctors acknowledged patient-initiated actions, and did not assess whether the responses of doctors fully addressed (i.e., attended to) patients’ concerns. For example, did doctor-responsive actions focus directly and empathically to the stated concerns of patients, and/or were patients’ concerns acknowledged yet dismissed with terminating utterances? Finally, a demand effect probably inflates communication satisfaction reports of new patients (see Figure 2). Because much is at stake as cancer care unfolds, patients can be expected to attribute high competency and expertise at the outset of cancer journeys. It would be normal to expect that patients hope to build a caring, and potentially long-term relationship, with doctors they are meeting for the first time.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment is extended to anonymous reviewers for helpful insights and suggestions.

Footnotes

Support for this study has been provided by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, USA (CA122472).

Contributor Information

Wayne A. Beach, Email: wbeach@mail.sdsu.edu, Professor, School of Communication, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182-4561, Phone: (619) 594-4948, FAX: (619) 594-0704, Adjunct Professor, Department of Surgery, Member, Moores Cancer Center, University of California, San Diego

David M. Dozier, Professor, Public Relations Emphasis, School of Journalism & Media Studies, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182-4561

References

- Albrecht TL, Blanchard C, Ruckdeschel JC, Coovert M, Strongbow R. Strategic physician communication and oncology clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17:3324–3332. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baile WF, Lenzi R, Kudelka AP, Meyers EG, Novack D, Goldstein M, Maguire P, Bast RC. Improving physician-patient communication in cancer care: Outcome of a workshop for oncologists. Journal of Cancer Education. 1997;12:166–173. doi: 10.1080/08858199709528481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baile WF, Aaron J. Patient-physician communication in oncology: Past, present, and future. Current opinions in oncology. 2005;17:331–335. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000167738.49325.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balint M. The doctor, his patient, and the illness. Madison, CT: International University Press; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA. Stability and ambiguity: Managing uncertain moments when updating news about mom’s cancer. Text. 2001;21:221–250. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Anderson JK. Communication and cancer?: The noticeable absence of interactional research. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2003;21:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Easter DW, Good JS, Pigeron E. Disclosing and responding to cancer “fears” during oncology interviews. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;60:893–910. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Mandelbaum J. “my mom had a stroke”: Understanding how patients raise and providers respond to psychosocial concerns. In: Harter LH, Japp PM, Beck CM, editors. Constructing our health: The implications of narrative for enacting illness and wellness. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. pp. 343–364. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA. A natural history of family cancer: Interactional resources for managing illness. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA. Patients’ efforts to justify wellness in a comprehensive cancer clinic. Health Communication. 2013a;28:577–591. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.704544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA. Handbook of patient-provider relationships: Raising and responding to primary concerns about health, illness, and disease. New York, NY: Hampton Press, Inc; 2013b. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA. Managing hopeful moments: Initiating and responding to delicate concerns about illness and health. In: Hamilton HE, Chou WS, editors. Handbook of language and health communication. New York: Routledge; 2014. pp. 459–476. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA. Doctor-patient interactions. In: Tracy K, editor. Encyclopedia of language and social interaction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Bensing JM. Doctor–patient communication and the quality of care. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;32:1301–1310. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90047-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne PS, Long BEL. Doctors talking to patients: A study of the verbal behavior of general practitioners consulting in their surgeries. London: H.M. Stationary Office; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Drew P. The voice of the patient: Non-alignment between patients and doctors in the consultation. In: Beach W, editor. Handbook of patient-provider relationships: Raising and responding to primary concerns about health, illness, and disease. New York, NY: Hampton Press, Inc; 2013. pp. 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RM, Street RL. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: Promoting healing and reducing suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. NIH Publication No. 07–6225. [Google Scholar]

- Facione N. Delay verses help seeking for breast cancer symptoms: A critical review of the literature on patient and provider delay. Social Science & Medicine. 1993;36:1521–1534. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90340-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Effective communication skills are the key to good cancer care. European Journal of Cancer. 1999;35:1592–1597. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford S, Fallowfield L, Lewis S. Doctor– patient interaction in oncology. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;42:1511–1519. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel RM, Quill TE, McDaniel SH. The biopsychosocial approach: Past, present, and future. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gill VT. Doing attributions in medical interactions: Patients’ explanations for illness and doctor’s responses. Social Psychological Quarterly. 1998;61:342–360. [Google Scholar]

- Gill VT, Halkowski T, Roberts F. Accomplishing a request without making one: A single case analysis of a primary care visit. Text. 2001:55–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gill VT, Maynard DW. Explaining illness: Patients’ proposals and physicians’ responses. In: Heritage J, Maynard D, editors. Communication and medicine: Talk and action in primary care consultations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 115–150. [Google Scholar]

- Gill VT, Pomerantz A, Denvir P. Preemptive resistance: Patients’ participation in diagnostic sense-making activities. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2010;32:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groopman J. The anatomy of hope: How people prevail in the face of illness. New York: Random House; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Halkowski T. ‘Occasional’ drinking: Some uses of a non-standard temporal metric in primary care assessment of alcohol use. In: Beach W, editor. Handbook of patient-provider relationships: Raising and responding to primary concerns about health, illness, and disease. New York, NY: Hampton Press, Inc; 2013. pp. 321–329. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J. Revisiting authority in physician-patient interaction. In: Duchan JF, Kovarsky D, editors. Diagnosis in cultural practice. New York, NY: Mouton De Gruyter; 2005. pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J, Maynard D, editors. Communication and medicine: Talk and action in primary care consultations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Workshop proceedings. Washington D.C: The National Academies Press; 2014. Partnering with patients to drive shared decisions, better value, and care improvement. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: Development and psychometric evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1992;17:1251–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui TS, Carter WB, Kukull WA, Haigh VH. Out-come-based doctor–patient interaction analysis I. Comparison of techniques. Medical Care. 1982;20:535–549. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198206000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Beach WA. “I just wanna know why”: Patients’ attempts and physicians’ responses to premature solicitation of diagnostic information. In: Duchan JF, Kovarsky D, editors. Diagnosis as cultural practice. New York: Mouton de Gruyter Publishers; 2005. pp. 103–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kennifer SL, Alexander SC, Pollak KI, Jeffreys AS, Olsen MK, Rodriguez KL, Arnold RM, Tulsky JA. Negative emotions in cancer care: Do oncologists’ responses depend on severity and type of emotion? Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;76:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsch BM, Negrete VF. Doctor-patient communication. Scientific American. 1972;227:66–74. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0872-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjanson LJ, Ashcroft T. The family’s cancer journey: A literature review. Cancer Nursing. 1994;17:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson W, Gorawara-Bhat &, Lamb J. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1021–1027. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.8.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutfey K, Maynard DW. Bad news in oncology: How physician and patient talk about death and dying without using those words. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1998;61:321–341. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire P, Booth K, Elliott C, Jones B. Helping health professionals involved in cancer care acquire key interviewing skills—the impact of workshops. European Journal of Cancer. 1996;32A:1486–1489. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvel MK, Epstein RM, Flowers K, Beckman HB. Soliciting the patient’s agenda: Have we improved? Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:283– 287. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard DW. Good news, bad news: Conversational order in everyday talk and clinical settings. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard DW, Frankel RM. On the edge of rationality in primary care medicine: Bad news, good news, and uncertainty. In: Heritage J, Maynard DW, editors. Communication and medicine: Talk and action in primary care consultations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 248–278. [Google Scholar]

- Mishel M. Uncertainty in illness scales manual. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mishler E. The discourse of medicine: Dialectics of medical interviews. Norwood, N.J: Ablex; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Nylenna M. Fear of cancer among patients in general practice. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 1984;2:24–26. doi: 10.3109/02813438409017697. suppl1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong LML, Visser MRM, Kruyver IPM, Bensing JM. The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS) in oncological consultations: Psychometric properties. Psycho-Oncology. 1998;7:387–401. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(1998090)7:5<387::AID-PON316>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peräkylä A. Agency and authority: Extended responses to diagnostic statements in primary care encounters. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 2002;35:219–247. [Google Scholar]

- Peräkylä A, Sorjonen ML. Emotion in interaction. Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, Alexander SC, Olsen MK, Abermethy AP, Sugg Skinner CS, Rodriguez KL, Tulsky JA. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:5748–5752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz E, Rintel S. Practices for reporting and responding to test results during medical consultations: Enacting the roles of paternalism and independent expertise. Discourse Studies. 2004;6:9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts F. The interactional construction of asymmetry: The medical agenda as a resource for delaying response to patients’ questions. Sociological Quarterly. 2000;41:151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SR, Early GL, Lamb J. Anxiety levels and cancer fear in patients admitted for elective operations. Southern Medical Journal. 1990;83:1128–1130. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JD. Asymmetry in action: Sequential resources in the negotiation of a prescription request. Text. 2001:19–54. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JD. An interactional structure of medical activities during acute visits and its implications for patients’ participation. Health Communication. 2003;15:27–59. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1501_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JD, Heritage J. Physician’s opening questions and patient. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;60:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JD, Hoover DR, Venetis MK, Kearney TJ, Street RL. Consultations between breast-cancer patients and surgeons: A pathway from patient-centered communication to reduced hopelessness. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:351–358. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roter DL. The Roter method of interaction process analysis. RIAS Manual 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Roter D. The enduring and evolving nature of the patient-physician relationship. Patient Education and Counseling. 2000;39:5–15. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roter DL, Hall JA, Katz NR. Relations between physicians’ behaviors and analogue patients’ satisfaction, recall, and impressions. Medical Care. 1987;25:437–451. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198705000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roter DL, Hall JA, Katz NR. Patient–physician communication: A descriptive summary of the literature. Patient Education and Counseling. 1988;12:99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Roter DL, Frankel RM, Hall JA, Sluyter D. The expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior in medical visits. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:28–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00306.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruusuvuori J. Emotion, affect, and conversation. In: Sidnell J, Stivers T, editors. Handbook of conversation analysis. Cambridge University Press; 2013. pp. 330–349. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield PE, Butow PN, Thompson JF, Tattersall MHN, Beeney LJ, Dunn SM. Psychological responses of patients receiving a diagnosis of cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2002;14:48–56. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholmerich J, Sedlak P, Hoppe-Seyler P, Garok W. The information needs and fears of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1987;34:182–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidnell J, Stivers T. Handbook of conversation analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Siminoff LA, Step MM. A comprehensive observational coding scheme for analyzing instrumental, affective, and relational communication in health care contexts. Journal of Health Communication. 2011;16:178–197. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.535109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiles WB, Putnam SM, Wolf MH, James SA. Interaction exchange structure and patient satisfaction with medical interviews. Medical Care. 1979;27:667–681. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197906000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stivers T, Heritage J. Breaking the sequential mold: Answering ‘more than the question’ during comprehensive history taking. Text. 2001;21:151–185. [Google Scholar]

- Street RL, Jr, Millay B. Analyzing patient participation in medical encounters. Health Communication. 2001;13:61–73. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1301_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street RL, Krupat E, Bell RA, Kravitz RL, Haidet P. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:609–616. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street RL, Gordan HS, Ward MM, Krupat E, Kravitz RL. Patient participation in medical consultations: Why some patients are more involved than others. Medical Care. 2005;43:960–969. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000178172.40344.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchman A, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277:678–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surbonne A, Zwitter M. Communication with the cancer patient: Information and truth. New York: The New York Academy of Sciences; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent J. The state of cancer care in America, 2014: A report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2014;10:119–143. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venetis MK, Robinson JD, Kearney T. Consulting with surgeons prior to breast-cancer surgery: Exploring the negative association between patients’ self-initiated questions and aspects of patients’ satisfaction. Journal of Health Communication in press. [Google Scholar]

- Venetis MK, Robinson JD, Kearney T. Breast-cancer patients’ participation behavior and coping during pre-surgical consultations: A pilot study. Health Communication. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.943633. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venetis MK, Robinson JD, Turkiewicz KL, Allen M. An evidence base for patient-centered care: A meta-analysis of studies of observed communication between cancer specialists and their patients. Patient Education & Counseling. 2009;77:379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waitzkin H. The politics of medical encounters. New Haven CT: Yale University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ward MM, Sundarmurthy S, Lotstein D, Bush TM, Neuwelt CM, Street RL. Participatory patient-physician communication and morbidity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis rheumatology. 2003;49:810–818. doi: 10.1002/art.11467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West C. Routine complications: Troubles with talk between doctors and patients. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- West HF, Baile WF. “Tell me what you understand”: The importance of checking for patient understanding. The Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2010;8:216–218. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]