Abstract

Different models of experimental allergic asthma have shown that the TLR7/8 agonist resiquimod (R848) is a potential inhibitor of type 2 helper cell–driven inflammatory responses. However, the mechanisms mediating its therapeutic effects are not fully understood. Using a model of experimental allergic asthma, we show that induction of IL-27 by R848 is critical for the observed ameliorative effects. R848 significantly inhibited all hallmarks of experimental allergic asthma, including airway hyperreactivity, eosinophilic airway inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, and Ag-specific Ig production. Whereas R848 significantly reduced IL-5, IL-13, and IL-17, it induced IFN-γ and IL-27. Neutralization of IL-27 completely reversed the therapeutic effect of R848 in the experimental asthma model, demonstrating dependence of R848-mediated suppression on IL-27. In vitro, R848 induced production of IL-27 by murine alveolar macrophages and dendritic cells and enhanced expression of programmed death–ligand 1, whose expression on monocytes and dendritic cells has been shown to regulate peripheral tolerance in both murine and human studies. Moreover, in vitro IL-27 enhanced secretion of IFN-γ whereas it inhibited IL-5 and IL-13, demonstrating its direct effect on attenuating Th2 responses. Taken together, our study proves that R848-mediated suppression of experimental asthma is dependent on IL-27. These data provide evidence of a central role of IL-27 for the control of Th2-mediated allergic diseases.

Introduction

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases, affecting ∼300 million people worldwide (1). It is a heterogeneous disease with different clinical endotypes that share the typical features of airway inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, and reversible airway obstruction (2). Asthma affects patients from infancy to senior age and is associated with high morbidity and health care costs (2–4). Although symptoms can be controlled in most patients by the use of anti-inflammatory and bronchospasmolytic drugs (5), they remain uncontrolled in ∼10% of patients (6, 7). Progress in development of novel treatment strategies for asthma has been relatively slow, and treatment guidelines are primarily based on clinical symptoms rather than underlying mechanisms of pathogenesis. So far, no curative therapies or even effective primary prevention strategies exist.

The origin of asthma is multifactorial with both genetic predisposition and environmental factors contributing to an increased disease risk (8, 9). One of the most common origins of asthma is sensitization to allergens in atopic patients resulting in a type 2 polarization of Th cells in response to allergen contact (10). Immune modulatory attempts have aimed at redirecting this inappropriate Th2 response toward allergens and inducing a counterbalancing Th1 or regulatory T cell response (11). Central components in these immunotherapeutic attempts are TLRs, key players of the innate immune system that mediate recognition and response to various microbial and viral pathogens (12, 13). TLR7 and TLR8 are receptors with high affinity for viral ssRNA (14). TLR7 is expressed most abundantly on plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DCs), myeloid DCs, B cells, and epithelial cells (15), whereas TLR8 is mainly expressed on monocytes, myeloid DCs, and neutrophils (14, 16–18).

R848 (resiquimod) is an imidazoquinoline compound initially developed as a potential antiviral agent that exerts its immunostimulatory function via mouse TLR7 as well as human TLR7 and TLR8 (19–21). It activates APCs via the MyD88 pathway, leading to induction of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, especially large amounts of type 1 IFNs (22). In different rodent models of experimental asthma, R848 effectively inhibited the development of asthma and even reversed already established asthma symptoms after systemic and intranasal application (18, 23–25).

In these studies, the R848-mediated effect was mostly attributed to its ability to induce IFN-γ by NKT, NK, or CD8+ T cells (23, 26). However, IFN-γ cannot solely account for the protective effect because the R848-mediated protection is neither abolished in IFN-γ–deficient mice nor through depletion of NKT cells (23, 26). In addition to inducing IFN-γ (18), application of R848 enhanced secretion of IL-27 in human and murine cells (27, 28). Moreover, in allergen-induced airway inflammation models, secretion of IL-27 together with IFN-γ was essential for attenuation of the Th2 response (29).

IL-27 is a member of the IL-12 family and primarily produced by activated DCs and pulmonary macrophages (30–32). This heterodimeric cytokine binds to the IL-27 receptor and gp130 to activate STAT1 (33–35) and induce Th1 cell differentiation (32, 36) whereas it directly suppresses Th2 and Th17 differentiation (37). Very recently, it was shown in different models of lung inflammation, including allergic inflammation and viral respiratory tract infection, that IFNs and IL-27 regulate the function of group 2 innate lymphoid cells and thereby together restrict type 2 immune responses (38–40). Using a model of immune perturbation, Molofsky et al. (41) have also shown that a counterregulatory mechanism involving IFN-γ and IL-33 is involved in regulating type 2 innate lymphoid cells and thereby maintenance of immune homeostasis.

In this study, we aimed at further elucidating the immunological mechanism underlying the therapeutic effect of R848 in experimental asthma. In a murine asthma model, intranasal application of R848 efficiently inhibited the asthma phenotype, including airway hyperreactivity (AHR), airway inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, and Th2 cytokine production, confirming findings of previous studies in asthma models (18, 23–26). Furthermore, R848 strongly induced IL-27 secretion, which was crucial for its therapeutic effect as demonstrated by in vivo neutralization of IL-27 via an mAb. In vitro, R848 induced IL-27 production in murine pulmonary APCs and upregulated programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1), a ligand critically involved in tolerance mechanisms (42, 43), on murine and human monocytes and DCs. Our data demonstrate a crucial role of IL-27 for the therapeutic effect of R848 in an experimental model of allergic asthma and support the impact of IL-27 for the control of Th2-mediated diseases.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6N wild-type mice (6–8 wk of age) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany). Animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility of Hannover Medical School. All animal experiments were performed according to institutional and state guidelines. The Committee on Animal Welfare of the state of Lower Saxony in Germany approved all animal protocols used in this study.

Asthma protocol and treatment with R848

To induce an allergic asthma phenotype, mice were immunized with the model allergen OVA (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany). The contaminating LPS in Sigma OVA (grade V, LPS content of ≥1500 endotoxin units/mg protein) was removed by Detoxi-Gel endotoxin-removing gel columns (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) to a level of <10 endotoxin units/mg protein, which was confirmed with Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Cambrex Bio Science, Walkersville, MD). Mice were i.p. sensitized with OVA (20 μg in 200 μl of 0.9% NaCl, Fig. 1A) adsorbed to 2 mg of an aqueous solution of aluminum hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide (Imject Alum; Perbio Science, Bonn, Germany) on days 0 and 7, followed by daily OVA challenges on days 15–17 by intranasal administration of 20 μg of OVA in 40 μl of 0.9% NaCl or in the case of Alum group challenged only with 0.9% NaCl solution. AHR was measured on day 18 and mice were sacrificed immediately afterward.

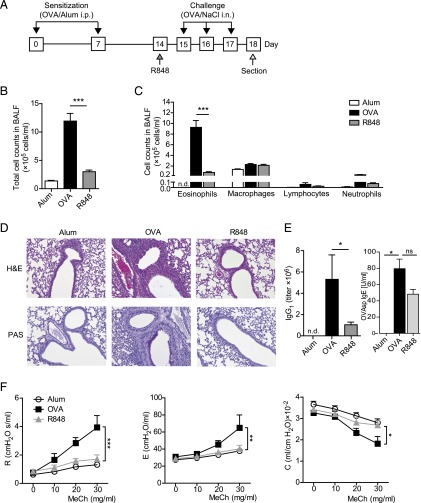

FIGURE 1.

Treatment with R848 alleviates airway inflammation and mucus hypersecretion in a model of experimental allergic asthma. Wild-type animals were subjected to the experimental asthma model and challenged with OVA alone (OVA), treated additionally with R848 before the first OVA challenge (R848), or treated with control vehicle only (Alum) (A). Total cell counts and eosinophilia in BALF (B and C) are shown. Reduced inflammation and mucus production in the lungs of treated animals, at original magnification ×20 (D) and attenuated levels of OVA-specific IgG1 and IgE in serum of control versus treated mice (E) are shown. Airway hyperresponsiveness after methacholine challenge was measured in an invasive lung function assay (F). Data are expressed as means ± SEM of three independent experiments with n ≥ 6 animals per group except for IgE measurements, in which two independent experiments were analyzed with n = 3–4 animals per group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Mice that were subjected to the asthma protocol are referred to as OVA, and Alum refers to control animals that received control solutions only without the model allergen at each time point. The group R848 constitutes mice that were subjected to the asthma protocol that received a treatment with 200 μg of R848 in 40 μl of 0.9% NaCl intranasally (InvivoGen Europe, Toulouse, France) 1 d before the OVA challenge period (see the protocol scheme in Fig. 1A).

In vivo neutralization of IL-27

In vivo neutralization of IL-27 was done by intranasal application of 40 μg of anti–IL-27 mAb (clone MM27-B1; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or appropriate isotypes as control 1 d before treatment with R848 as shown in Fig. 3A. Animals that were treated with the neutralizing mAb are referred to as R848 plus anti–IL-27, and those that received isotype control are termed R848 plus isotype.

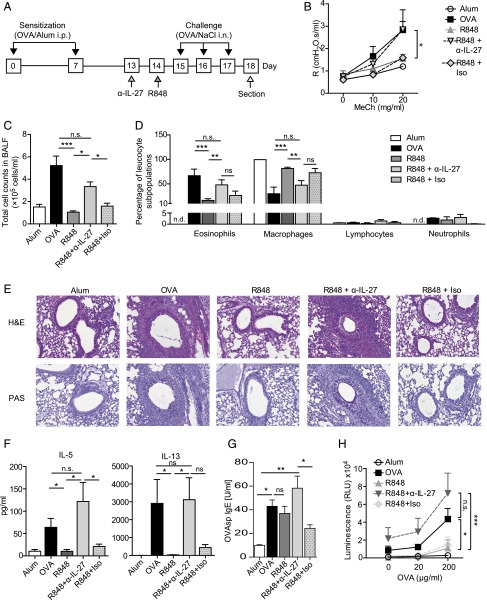

FIGURE 3.

The therapeutic effect of R848 on experimental allergic asthma is dependent on IL-27. Mice subjected to the asthma protocol were either pretreated with an IL-27–neutralizing Ab or isotype control or left untreated before application of R848 (A). Neutralization of IL-27 abrogated the beneficial effects of R848 as shown by increased AHR (B) and elevation of total BALF cell counts and eosinophilia (C and D). Increased eosinophilic airway inflammation and mucus secretion are shown in H&E- and PAS-stained lung sections, at original magnification ×20 (E). Effects of antagonizing IL-27 on Th2 cytokine production by BLN cells and IgE in serum of experimental animals (F and G) or activation/proliferation (H) of BLN cells stimulated ex vivo using OVA are shown. Data are expressed as means ± SEM of two to three independent experiments with n ≥ 4 animals per group.*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Measurement of AHR

AHR was assessed using invasive lung function as already described (44). Briefly, after tracheostomy, anesthetized mice were connected to the flexiVent system (Scireq, Montreal, QC, Canada) and exposed to different concentrations of aerosolized methacholine (0, 10, 20, and, where applicable, 30 mg/ml) in 0.9% NaCl. Snapshot perturbations for each dose of methacholine were used to measure resistance, compliance, and elastance of the respiratory system (airways, lung, and chest wall).

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid collection and lung histology

The left lung of each mouse was inflated with 0.4 ml of PBS containing 2 mM EDTA and tied off for histology. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of the right lung was obtained as described previously (45, 46). Lungs were fixed in 4% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm-thick sections were stained with H&E (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) or with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany). Lung sections were scanned using a Keyence BZ-9000 microscope (Keyence, Osaka, Japan).

Measurement of cytokine production and cell activation/proliferation in vitro

Bronchial lymph node (BLN) cells were isolated and restimulated in vitro (5 × 106 cells/well) with 0, 20, or 200 μg/ml OVA in culture medium (RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) for 3 d. For secretion of Th cytokines, BLN cells were in vitro restimulated in the presence of either 1 μg/ml R848 or 10 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL-27 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Alveolar macrophages (AMs) and lung DCs were isolated after homogenization and digestion of murine lungs using the gentleMACS system (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions to attain single-cell suspensions. Pure AMs and DCs were isolated from digested lungs through sorting based on the surface markers CD11c and MHC class II (MHC-II) as already described (47) with CD11cloMHC-IIhi cells representing lung DCs and the CD11hi population representing AMs (see Fig. 4A).Using further staining with Siglec-F, we demonstrated purity of AM and DC populations of >95%. In vitro stimulation of human monocytes and PBMCs as well as murine AMs and lung DCs was done with either 1 μg/ml R848 or 10 ng/ml recombinant murine or human IL-27 for a maximum of 48 h, and supernatants were collected for cytokine analysis. Cytokine production was measured using either ELISA (DuoSet; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or cytometric bead array (FlowCytomix; eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The number of viable cells was measured using a cell titer glow assay (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the cell suspension and freshly prepared cell titer glow reagent were mixed at a 1:1 ratio and measured using a multidetection plate reader system (Promega).

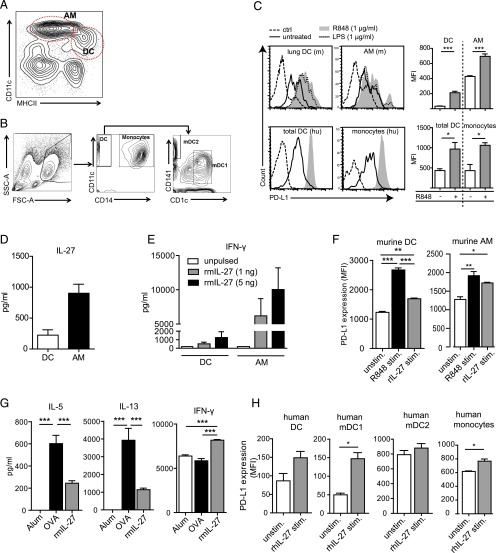

FIGURE 4.

Lung APCs produce IL-27 in response to R848, which impacts Th2/Th1 cytokine production and tolerogenic marker expression in murine and human APCs. Gating strategy for AMs and DCs in murine lungs (A) and staining strategy used for identification of human monocytes and DCs in peripheral blood (B) are shown. Murine AMs and DCs sorted from lungs of wild-type mice as well as human DCs and monocytes display increased expression of PD-L1 on stimulation with R848 (C). Additionally, murine AMs and DCs produce IL-27 on exposure to R848 (D). The dose-dependent influence of in vitro stimulation with recombinant murine IL-27 (rmIL-27) on IFN-γ production by murine DCs and AMs (E) and expression of PD-L1 (F) are shown. Reduced Th2 cytokine and IFN-γ production by BLN cells of allergic mice restimulated in presence of rmIL-27 (G). Enhanced expression of PD-L1 on human DCs and monocytes after in vitro stimulation with recombinant human IL-27 (rhIL-27) (H) is shown. Flow cytometry histograms are representative of one of two murine experiments or of DCs and monocytes from five human donors. Graphs display a summary of two to three independent experiments with means ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. rhIL-27, recombinant human IL-27; rmIL-27, recombinant murine IL-27.

Measurement of OVA-specific IgG1 and IgE

OVA-specific IgG1 and IgE serum levels were measured by ELISA according to a standard protocol as described previously (46, 48).

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were incubated with fluorescently labeled Abs for 30 min at 4°C in staining buffer (PBS with 0.5% BSA). Abs used in this study included CD3 (145-2C11), CD4 (RM4-5), and CD25 (PC61) from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA) and Foxp3 (FJK-16s) from eBioscience. Intracellular staining of Foxp3 was performed using intracellular staining buffers according to the manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience). For identification of murine APCs and expression of B7-H1 (PD-L1), the following Abs were used: CD11c (clone N418), CD11b (clone M1/70), MHC-II (clone M5/114.15.2), CD8 (clone 53-6.7), and CD274 (clone 10F.9G2) (all from BioLegend). Characterization of human monocytes and DCs in the PBMCs was done as follows: CD11c-expressing cells were taken as myeloid DCs and further classified into either mDC1 or mDC2 based on expression of CD1c or CD141, respectively (49) (Fig. 4B). These mDC1 and mDC2 subclassifications are important because these DC subsets found in the peripheral blood have been shown to be functionally distinct as exemplified through Ag presentation mechanisms (49) as well as cytokine secretion in response to Ags (50). CD14-expressing cells were categorized as monocytes (see Fig. 4B).The following Abs were used for this characterization: CD14, CD11c, CD141, CD1c, and CD274 (BioLegend). Flow cytometry data were collected using a FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo version 10 (FlowJo, Ashland, OR).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism V software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). The Mann–Whitney U test was used for determination of the significance of differences between two groups. One-way and two-way ANOVAs with Bonferroni multiple comparisons testing were used to determine statistical significances in groups larger than two. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. Numbers of mice or pooled samples per experimental group are indicated in each figure legend.

Results

R848 alleviates the hallmarks of experimental allergic asthma

To test the potential of TLR7/8 ligand R848 in ameliorating murine asthma, mice that were immunized with OVA according to the asthma protocol shown in Materials and Methods received R848 intranasally 1 d prior to the first intrapulmonary OVA challenge (Fig. 1A). R848 treatment significantly reduced all hallmark characteristics associated with experimental asthma. Cell counts in the BALF and BALF eosinophilia were significantly reduced (Fig. 1B, 1C), and peribronchiolar and perivascular eosinophilic infiltrates as well as airway mucus hypersecretion were significantly decreased compared with the nontreated allergic mice (Fig. 1D). Moreover, R848 treatment effectively inhibited serum levels of OVA-specific IgG1 and attenuated levels of IgE (Fig. 1E) and reversed methacholine-induced AHR as reflected by a normalization of both airway resistance and elastance and an elevation of lung compliance (Fig. 1F). In summary, these results demonstrate the therapeutic effect of R848 in experimental asthma.

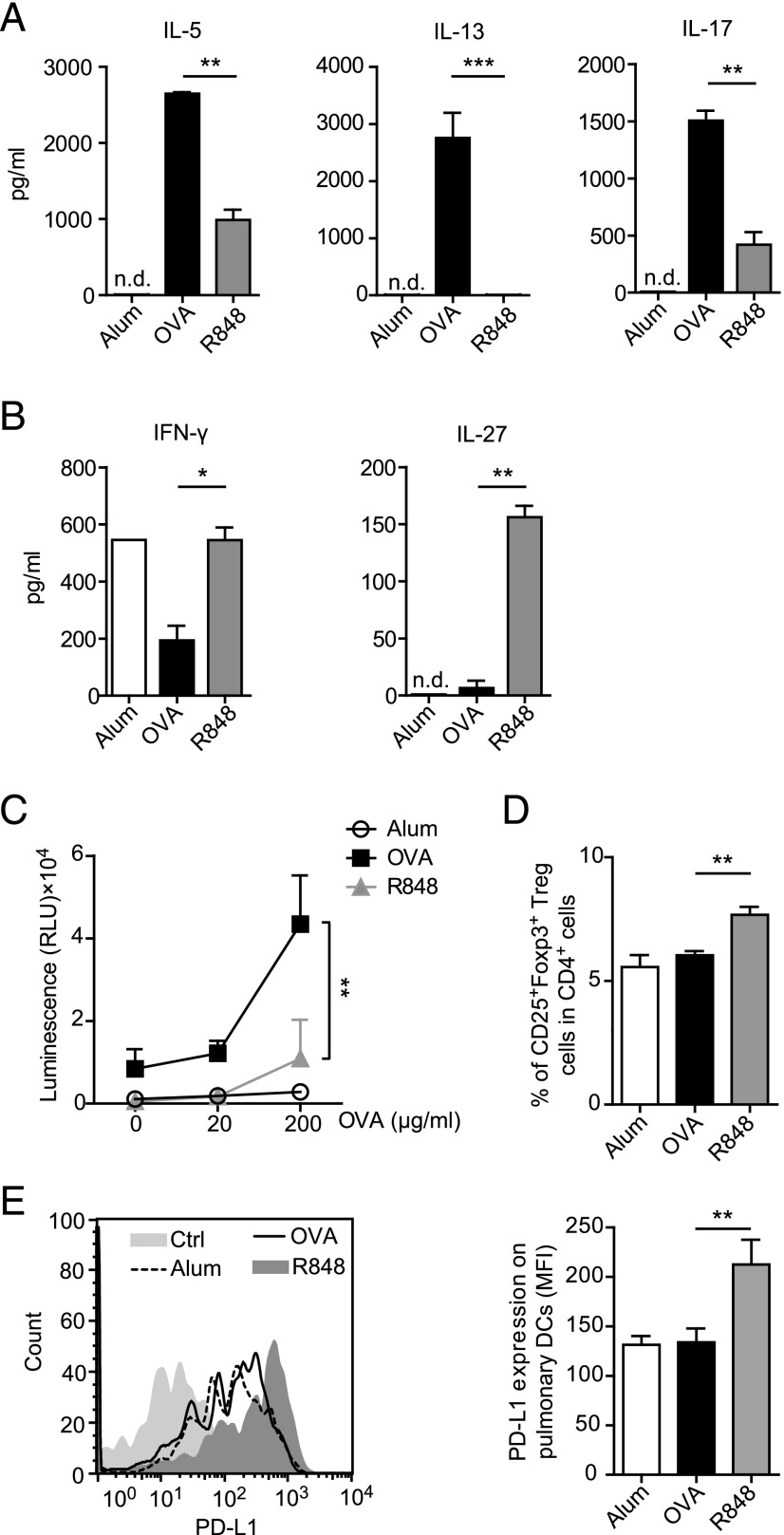

R848 inhibits production of IL-4, IL-13, and IL-17 whereas it induces IFN-γ and IL-27

To assess the influence of R848 treatment on Th cell polarization in our model, we performed cytokine screening in the supernatant of OVA-restimulated BLN cells. Treatment of sensitized mice with R848 before the first intranasal challenge (R848 group) led to a significant reduction of Th2 cytokines (IL-5 and IL-13), Th17 cytokine (IL-17), and a significant induction of the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ and IL-27 (Fig. 2A, 2B). After in vivo application of R848, a marked decrease in Ag-specific activation/proliferation of BLN cells was observed (Fig. 2C), whereas the percentage of regulatory T cells was significantly elevated (Fig. 2D). Additionally, the expression of PD-L1, a ligand that plays a crucial role in tolerance-inducing mechanisms (42, 43), was significantly increased on pulmonary DCs isolated from mice that were exposed to R848 (Fig. 2E).

FIGURE 2.

R848 reduces Th2 and Th17 cytokines but enhances production of IL-27 and IFN-γ. On restimulation with the allergen, BLN cells from the R848 group displayed a decreased Th2 cytokine production and increased expression of IFN-γ and IL-27 (A and B) compared with those from allergic mice (OVA). Ex vivo proliferation of BLN cells after restimulation with OVA (C) and frequencies of regulatory T cells in BLN (D) are shown. PD-L1 expression on lung DCs in mice subjected to the asthma protocol after application of R848 (E) is shown. Data are expressed as means ± SEM of two to three independent experiments with n ≥ 6 animals per group. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

IL-27 is crucial in R848-mediated amelioration of experimental asthma

As IL-27 has been reported to directly suppress Th2 cell development and Th2 cytokine production (29, 51), we next addressed the mechanistic relevance of R848-induced IL-27 in our model. To this end, IL-27 was blocked in vivo with an antagonizing mAb that was applied intranasally 1 d before R848 treatment of sensitized mice a week after the last sensitization (Fig. 3A). Neutralization of IL-27 with anti–IL-27 mAb significantly inhibited the therapeutic effect of R848. Anti–IL-27 treatment inhibited R848-induced protection from AHR as reflected by a significantly elevated airway resistance in R848/anti–IL-27-treated mice (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, a significant increase in total BALF cell numbers and eosinophilic infiltration (Fig. 3C, 3D), as well as an increased airway inflammation and mucus hypersecretion in H&E- and PAS-stained lung sections (Fig. 3E), was observed upon IL-27 blockade in the R848-treated mice. Moreover, restimulated BLN cells isolated from R848-treated mice after neutralization of IL-27 by an mAb produced more Ag-specific Th2 cytokines (Fig. 3F) and displayed an increased Ag-specific activation/proliferation (Fig. 3H). Meanwhile, OVA-specific IgE was elevated after neutralization of IL-27 (Fig. 3G). Taken together, inhibition of IL-27 abrogated the protective effect of R848 in our model.

IL-27 is produced by AMs and DCs and has direct tolerogenic effects on murine as well as human APCs

We next sorted murine AMs and pulmonary DCs (Fig. 4A) from lungs of wild-type mice and stimulated them in vitro with R848. Upon stimulation with R848, both murine AMs and DCs upregulated PD-L1 (Fig. 4C) and secreted IL-27 (Fig. 4D), a marker strongly associated with tolerogenic APCs (42, 43). The secretion of IL-27 in our model was much higher in AMs as compared with DCs (Fig. 4D). Upregulation of PD-L1 upon R848 stimulation was also observed in human monocytes and DCs (Fig. 4B) after in vitro stimulation of human PBMCs (Fig. 4C).

To determine the direct effect IL-27 has on AMs and DCs, we stimulated murine AMs and DCs in vitro with rIL-27, which led to IFN-γ secretion in both cell types in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, application of IL-27, similar to R848 stimulation, resulted in upregulation of PD-L1 in murine as well as human APCs (Fig. 4F, 4H). Next, we stimulated murine BLN cells isolated from allergic mice with OVA in the presence of IL-27. IL-27 stimulation significantly induced IFN-γ secretion but suppressed secretion of the Th2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 (Fig. 4G). In summary, our data show that IL-27 is produced by pulmonary APCs upon R848 stimulation, directly activates IFN-γ secretion by these APCs, and upregulates PDL-1 on their surface. Additionally, IL-27 dampens production of Th2 cytokines by Ag-experienced helper cells in this model of allergic asthma.

Discussion

In the present study, we aimed at elucidating the mechanisms involved in alleviation of murine allergic asthma by the TLR7/8 agonist R848 (resiquimod). We first confirmed previous findings that R848 significantly inhibits all hallmarks of allergic asthma, including AHR, eosinophilic airway inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, and Th2 as well as Th17 cytokine production whereas it simultaneously induces the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ (18, 23, 26, 52). Additionally, we show in our model of experimental asthma that R848 strongly induced IL-27, a cytokine of the IL-12 family, and that blocking IL-27 by a monoclonal anti–IL-27 Ab completely reversed the protective effect of R848. These data demonstrate, to our knowledge for the first time, the central role of IL-27 signaling for the therapeutic effect of R848 in experimental asthma.

Previously, it has been shown that R848 exerts its immunostimulatory function via mouse TLR7 as well as human TLR7 and TLR8 (19–21) by activating APCs via the MyD88 pathway, leading to induction of large amounts of type 1 IFNs (22). In accordance with other mouse asthma models (18, 23–25, 52), we also observed a strong induction of IFN-γ and inhibition of the Th2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 as well as inhibition of the Th17 cytokine IL-17 after intranasal application of R848.

So far, the R848-mediated effect has been mostly attributed either to NKT cells or to NK or CD8+ T cell–derived IFN-γ. However, because the protective effect was not abolished in IFN-γ–deficient mice or by depletion of CD8+ T cells (23, 26), IFN-γ cannot solely account for the protective effect of R848. In our study, we show, to our knowledge for the first time, a strong induction of IL-27 by R848 treatment in experimental asthma. This heterodimeric IL-12–related cytokine was secreted in cell culture supernatants from lung-draining lymph node cells that we had isolated from R848-treated asthmatic mice. Moreover, IL-27 was strongly secreted after application of R848 to AMs or pulmonary DCs in vitro, demonstrating also a direct effect of R848 on pulmonary APCs.

The central role of IL-27 for the R848-mediated effect in our model became prominent when we inhibited IL-27 by applying a monoclonal anti–IL-27 Ab. This inhibition of IL-27 significantly reversed the R848-mediated protective effects on the clinical features of asthma such as AHR and eosinophilic airway inflammation. Initially, IL-27 was described as an important trigger of Th1 responses, and more recent studies implicated this factor in the negative regulation of Th17 cells (53, 54). In agreement, we observed that inhibition of IL-27 completely re-established secretion of Th2 and Th17 cytokines that was inhibited by R848 treatment. Application of anti–IL-27 mAb alone, without inhibition of IFN-γ or depletion of NK cells, was sufficient to reverse the R848-mediated protective effects in asthma, supporting its central role in regulation of the R848 effect.

Using IL-27Rα–deficient mice, it was shown previously in Th2-associated murine models of asthma or parasitic infections that IL-27Rα deficiency results in exacerbated lung pathology and airway hyperresponsiveness (55–57). These findings are in accordance with our observation that IL-27 has an immunoprotective role in Th2-mediated disease allergic asthma. Very recent studies provided evidence that IL-27 as well as type I and type II IFNs are able to suppress group 2 innate lymphoid cell responses in vitro and in vivo (38, 40) and suggested that this mechanism is next to IFN-γ induction in importance for the immunoregulation via IL-27 of type 2 immune responses.

Another mechanism that has been shown to be part of the regulatory properties of IL-27 is enhancement of negative costimulatory molecules on the surface of APCs (43, 58). In our study, we show that IL-27 is produced by pulmonary APCs upon R848 stimulation, directly activates IFN-γ secretion by these APCs, and upregulates the ligand of the costimulatory molecule programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), that is, PD-L1, on their surface in a dose-dependent manner. PD-L1 is strongly associated with tolerogenic APCs (42, 43), delivering inhibitory signals that regulate the balance between T cell activation, tolerance, and immunopathology of the immune response (59). We observed upregulation of PD-L1 upon R848 stimulation in murine APCs as well as human monocytes and DCs after in vitro stimulation of human PBMCs. Our findings point toward a mechanism of R848 in experimental asthma involving the secretion of IL-27 and upregulation of tolerogenic markers on pulmonary APCs after intranasal R848 application. IL-27 then in turn influences both APCs and T cells to produce IFN-γ and thereby suppress Th2 polarization. The observation that R848 stimulation leads to upregulation of the tolerogenic marker PD-L1 in both murine and human cells supports the notion that these immunological processes may not only be relevant in the murine system but, in the long run, could also contribute to the further development of novel treatment strategies in asthma.

In summary, we have shown in this study that application of R848 induces IL-27 by pulmonary APCs (DCs and AMs), which in our model appears to be central for mediating the Th1 priming properties of this TLR agonist. The heterodimeric IL-27 cytokine usually binds its receptor complex composed of IL-27Rα/WSX-1 and gp130 to activate STAT1 and induce Th1 cell differentiation (32–36). The IL-27Rα/WSX-1 receptor is abundantly expressed on CD4+ T cells, and its binding by IL-27 leads to polarization of naive Th cells toward Th1 and thus inhibition of Th2 cytokine production in activated T cells (60). Moreover, our data show that IL-27 also leads to enhanced IFN-γ production and upregulation of PD-L1 in APCs (Fig. 4C, 4E). PD-L1 is a ligand for the negative costimulatory molecule PD-1, and this signaling pathway has been shown to compromise functions of Ag-specific T cells (61). Through upregulation of PD-L1, IFN-γ leads to induction of tolerogenic properties in DCs (43, 58), which acquire the capability to effectively suppress T cell responses in a PD-L1/PD-1–dependent manner (42, 62, 63). Furthermore, the ability of IL-27 as an inducer of tolerogenic DCs was recently confirmed in a clinical study in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that provided evidence that IL-27–exposed DCs induced regulatory T cells in obstructive pulmonary disease patients (64). Taken together and in concordance with the current literature, our data suggest that IL-27 is the central cytokine mediating the antiallergic effect of R848 in our model. However, in our model, R848 had only a moderate effect on the IgE level, whereas inhibition of IgG1, which is also associated with a Th2-driven immune response in mice, was much more pronounced.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate IL-27 as the key player in R848-induced asthma amelioration and support a central role of IL-27 in regulation of Th2-mediated diseases such as allergic asthma.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jana Bergmann, Christin Albrecht, Anika Dreier, and Heike Grundmann for competent technical support.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Lungen Zentrum (to G.H.).

- AHR

- airway hyperreactivity

- AM

- alveolar macrophage

- BALF

- bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- BLN

- bronchial lymph node

- DC

- dendritic cell

- MHC-II

- MHC class II

- PAS

- periodic acid–Schiff

- PD-1

- programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1

- programmed death–ligand 1.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization 2015. Chronic Respiratory Diseases. Available at: http://www.who.int/respiratory/asthma/scope/en/. Accessed: October 11, 2016.

- 2.Wenzel S. E. 2012. Asthma phenotypes: the evolution from clinical to molecular approaches. Nat. Med. 18: 716–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haldar P., Pavord I. D., Shaw D. E., Berry M. A., Thomas M., Brightling C. E., Wardlaw A. J., Green R. H. 2008. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 178: 218–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansel T. T., Johnston S. L., Openshaw P. J. 2013. Microbes and mucosal immune responses in asthma. Lancet 381: 861–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Initiative for Asthma 2015. Pocket Guide for Asthma Management and Prevention. Available at: http://ginasthma.org/. Accessed: October 11, 2016.

- 6.Wenzel S. E. 2013. Complex phenotypes in asthma: current definitions. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 26: 710–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenzel S. E., Busse W. W. 2007. Severe asthma: lessons from the Severe Asthma Research Program. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 119: 14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyers D. A., Bleecker E. R., Holloway J. W., Holgate S. T. 2014. Asthma genetics and personalised medicine. Lancet Respir. Med. 2: 405–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Mutius E., Vercelli D. 2010. Farm living: effects on childhood asthma and allergy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10: 861–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fahy J. V. 2015. Type 2 inflammation in asthma—present in most, absent in many. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15: 57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen T. H., Casale T. B. 2011. Immune modulation for treatment of allergic disease. Immunol. Rev. 242: 258–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akira S., Uematsu S., Takeuchi O. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124: 783–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akira S. 2006. TLR signaling. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 311: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diebold S. S., Kaisho T., Hemmi H., Akira S., Reis e Sousa C. 2004. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science 303: 1529–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krieg A. M., Vollmer J. 2007. Toll-like receptors 7, 8, and 9: linking innate immunity to autoimmunity. Immunol. Rev. 220: 251–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heil F., Hemmi H., Hochrein H., Ampenberger F., Kirschning C., Akira S., Lipford G., Wagner H., Bauer S. 2004. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via Toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science 303: 1526–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lund J. M., Alexopoulou L., Sato A., Karow M., Adams N. C., Gale N. W., Iwasaki A., Flavell R. A. 2004. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 5598–5603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grela F., Aumeunier A., Bardel E., Van L. P., Bourgeois E., Vanoirbeek J., Leite-de-Moraes M., Schneider E., Dy M., Herbelin A., Thieblemont N. 2011. The TLR7 agonist R848 alleviates allergic inflammation by targeting invariant NKT cells to produce IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 186: 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van L. P., Bardel E., Gregoire S., Vanoirbeek J., Schneider E., Dy M., Thieblemont N. 2011. Treatment with the TLR7 agonist R848 induces regulatory T-cell-mediated suppression of established asthma symptoms. Eur. J. Immunol. 41: 1992–1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jurk M., Heil F., Vollmer J., Schetter C., Krieg A. M., Wagner H., Lipford G., Bauer S. 2002. Human TLR7 or TLR8 independently confer responsiveness to the antiviral compound R-848. Nat. Immunol. 3: 499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemmi H., Kaisho T., Takeuchi O., Sato S., Sanjo H., Hoshino K., Horiuchi T., Tomizawa H., Takeda K., Akira S. 2002. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 3: 196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawai T., Akira S. 2010. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 11: 373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xirakia C., Koltsida O., Stavropoulos A., Thanassopoulou A., Aidinis V., Sideras P., Andreakos E. 2010. Toll-like receptor 7-triggered immune response in the lung mediates acute and long-lasting suppression of experimental asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 181: 1207–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camateros P., Tamaoka M., Hassan M., Marino R., Moisan J., Marion D., Guiot M. C., Martin J. G., Radzioch D. 2007. Chronic asthma-induced airway remodeling is prevented by Toll-like receptor-7/8 ligand S28463. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175: 1241–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quarcoo D., Weixler S., Joachim R. A., Stock P., Kallinich T., Ahrens B., Hamelmann E. 2004. Resiquimod, a new immune response modifier from the family of imidazoquinolinamines, inhibits allergen-induced Th2 responses, airway inflammation and airway hyper-reactivity in mice. Clin. Exp. Allergy 34: 1314–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camateros P., Kanagaratham C., Henri J., Sladek R., Hudson T. J., Radzioch D. 2009. Modulation of the allergic asthma transcriptome following resiquimod treatment. Physiol. Genomics 38: 303–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdalla A. E., Li Q., Xie L., Xie J. 2015. Biology of IL-27 and its role in the host immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 11: 168–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pirhonen J., Sirén J., Julkunen I., Matikainen S. 2007. IFN-α regulates Toll-like receptor-mediated IL-27 gene expression in human macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82: 1185–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujita H., Teng A., Nozawa R., Takamoto-Matsui Y., Katagiri-Matsumura H., Ikezawa Z., Ishii Y. 2009. Production of both IL-27 and IFN-γ after the treatment with a ligand for invariant NK T cells is responsible for the suppression of Th2 response and allergic inflammation in a mouse experimental asthma model. J. Immunol. 183: 254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J. J., Wang W., Baines K. J., Bowden N. A., Hansbro P. M., Gibson P. G., Kumar R. K., Foster P. S., Yang M. 2010. IL-27/IFN-γ induce MyD88-dependent steroid-resistant airway hyperresponsiveness by inhibiting glucocorticoid signaling in macrophages. J. Immunol. 185: 4401–4409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owaki T., Asakawa M., Morishima N., Hata K., Fukai F., Matsui M., Mizuguchi J., Yoshimoto T. 2005. A role for IL-27 in early regulation of Th1 differentiation. J. Immunol. 175: 2191–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meka R. R., Venkatesha S. H., Dudics S., Acharya B., Moudgil K. D. 2015. IL-27-induced modulation of autoimmunity and its therapeutic potential. Autoimmun. Rev. 14: 1131–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villarino A., Hibbert L., Lieberman L., Wilson E., Mak T., Yoshida H., Kastelein R. A., Saris C., Hunter C. A. 2003. The IL-27R (WSX-1) is required to suppress T cell hyperactivity during infection. Immunity 19: 645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kastelein R. A., Hunter C. A., Cua D. J. 2007. Discovery and biology of IL-23 and IL-27: related but functionally distinct regulators of inflammation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25: 221–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter C. A. 2005. New IL-12-family members: IL-23 and IL-27, cytokines with divergent functions. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5: 521–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owaki T., Asakawa M., Fukai F., Mizuguchi J., Yoshimoto T. 2006. IL-27 induces Th1 differentiation via p38 MAPK/T-bet- and intercellular adhesion molecule-1/LFA-1/ERK1/2-dependent pathways. J. Immunol. 177: 7579–7587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amadi-Obi A., Yu C. R., Liu X., Mahdi R. M., Clarke G. L., Nussenblatt R. B., Gery I., Lee Y. S., Egwuagu C. E. 2007. TH17 cells contribute to uveitis and scleritis and are expanded by IL-2 and inhibited by IL-27/STAT1. Nat. Med. 13: 711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moro K., Kabata H., Tanabe M., Koga S., Takeno N., Mochizuki M., Fukunaga K., Asano K., Betsuyaku T., Koyasu S. 2016. Interferon and IL-27 antagonize the function of group 2 innate lymphoid cells and type 2 innate immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 17: 76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mchedlidze T., Kindermann M., Neves A. T., Voehringer D., Neurath M. F., Wirtz S. IL-27 suppresses type 2 immune responses in vivo via direct effects on group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duerr C. U., McCarthy C. D., Mindt B. C., Rubio M., Meli A. P., Pothlichet J., Eva M. M., Gauchat J. F., Qureshi S. T., Mazer B. D., et al. 2016. Type I interferon restricts type 2 immunopathology through the regulation of group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 17: 65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Molofsky A. B., Van Gool F., Liang H. E., Van Dyken S. J., Nussbaum J. C., Lee J., Bluestone J. A., Locksley R. M. 2015. Interleukin-33 and interferon-γ counter-regulate group 2 innate lymphoid cell activation during immune perturbation. Immunity 43: 161–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Unger W. W., Laban S., Kleijwegt F. S., van der Slik A. R., Roep B. O. 2009. Induction of Treg by monocyte-derived DC modulated by vitamin D3 or dexamethasone: differential role for PD-L1. Eur. J. Immunol. 39: 3147–3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsumoto K., Inoue H., Nakano T., Tsuda M., Yoshiura Y., Fukuyama S., Tsushima F., Hoshino T., Aizawa H., Akiba H., et al. 2004. B7-DC regulates asthmatic response by an IFN-γ-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 172: 2530–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoymann H. G. 2012. Lung function measurements in rodents in safety pharmacology studies. Front. Pharmacol. 3: 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Behrendt A. K., Hansen G. 2010. CD27 costimulation is not critical for the development of asthma and respiratory tolerance in a murine model. Immunol. Lett. 133: 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Polte T., Behrendt A. K., Hansen G. 2006. Direct evidence for a critical role of CD30 in the development of allergic asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 118: 942–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hartwig C., Mazzega M., Constabel H., Krishnaswamy J. K., Gessner J. E., Braun A., Tschernig T., Behrens G. M. 2010. Fcγ receptor-mediated antigen uptake by lung DC contributes to allergic airway hyper-responsiveness and inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 40: 1284–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albrecht M., Chen H. C., Preston-Hurlburt P., Ranney P., Hoymann H. G., Maxeiner J., Staudt V., Taube C., Bottomly H. K., Dittrich A. M. 2011. TH17 cells mediate pulmonary collateral priming. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 128: 168–177.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haniffa M., Shin A., Bigley V., McGovern N., Teo P., See P., Wasan P. S., Wang X. N., Malinarich F., Malleret B., et al. 2012. Human tissues contain CD141hi cross-presenting dendritic cells with functional homology to mouse CD103+ nonlymphoid dendritic cells. Immunity 37: 60–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kassianos A. J., Hardy M. Y., Ju X., Vijayan D., Ding Y., Vulink A. J., McDonald K. J., Jongbloed S. L., Wadley R. B., Wells C., et al. 2012. Human CD1c (BDCA-1)+ myeloid dendritic cells secrete IL-10 and display an immuno-regulatory phenotype and function in response to Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Immunol. 42: 1512–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakagawa R., Nagafune I., Tazunoki Y., Ehara H., Tomura H., Iijima R., Motoki K., Kamishohara M., Seki S. 2001. Mechanisms of the antimetastatic effect in the liver and of the hepatocyte injury induced by α-galactosylceramide in mice. J. Immunol. 166: 6578–6584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Antoniu S. A. 2011. Targeting the Toll-like receptor 7 pathway in asthma: a potential immunomodulatory approach? Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 15: 667–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neufert C., Becker C., Wirtz S., Fantini M. C., Weigmann B., Galle P. R., Neurath M. F. 2007. IL-27 controls the development of inducible regulatory T cells and Th17 cells via differential effects on STAT1. Eur. J. Immunol. 37: 1809–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stumhofer J. S., Laurence A., Wilson E. H., Huang E., Tato C. M., Johnson L. M., Villarino A. V., Huang Q., Yoshimura A., Sehy D., et al. 2006. Interleukin 27 negatively regulates the development of interleukin 17-producing T helper cells during chronic inflammation of the central nervous system. Nat. Immunol. 7: 937–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshimoto T., Yoshimoto T., Yasuda K., Mizuguchi J., Nakanishi K. 2007. IL-27 suppresses Th2 cell development and Th2 cytokines production from polarized Th2 cells: a novel therapeutic way for Th2-mediated allergic inflammation. J. Immunol. 179: 4415–4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miyazaki Y., Inoue H., Matsumura M., Matsumoto K., Nakano T., Tsuda M., Hamano S., Yoshimura A., Yoshida H. 2005. Exacerbation of experimental allergic asthma by augmented Th2 responses in WSX-1-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 175: 2401–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Artis D., Villarino A., Silverman M., He W., Thornton E. M., Mu S., Summer S., Covey T. M., Huang E., Yoshida H., et al. 2004. The IL-27 receptor (WSX-1) is an inhibitor of innate and adaptive elements of type 2 immunity. J. Immunol. 173: 5626–5634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee S. J., Jang B. C., Lee S. W., Yang Y. I., Suh S. I., Park Y. M., Oh S., Shin J. G., Yao S., Chen L., Choi I. H. 2006. Interferon regulatory factor-1 is prerequisite to the constitutive expression and IFN-γ-induced upregulation of B7-H1 (CD274). FEBS Lett. 580: 755–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keir M. E., Butte M. J., Freeman G. J., Sharpe A. H. 2008. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 26: 677–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pflanz S., Timans J. C., Cheung J., Rosales R., Kanzler H., Gilbert J., Hibbert L., Churakova T., Travis M., Vaisberg E., et al. 2002. IL-27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of EBI3 and p28 protein, induces proliferation of naive CD4+ T cells. Immunity 16: 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nguyen L. T., Ohashi P. S. 2015. Clinical blockade of PD1 and LAG3—potential mechanisms of action. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15: 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wölfle S. J., Strebovsky J., Bartz H., Sähr A., Arnold C., Kaiser C., Dalpke A. H., Heeg K. 2011. PD-L1 expression on tolerogenic APCs is controlled by STAT-3. Eur. J. Immunol. 41: 413–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayashi T., Yao S., Crain B., Promessi V. J., Shyu L., Sheng C., Kang M., Cottam H. B., Carson D. A., Corr M. 2015. Induction of tolerogenic dendritic cells by a PEGylated TLR7 ligand for treatment of type 1 diabetes. PLoS One 10: e0129867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsoumakidou M., Tousa S., Semitekolou M., Panagiotou P., Panagiotou A., Morianos I., Litsiou E., Trochoutsou A. I., Konstantinou M., Potaris K., et al. 2014. Tolerogenic signaling by pulmonary CD1c+ dendritic cells induces regulatory T cells in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by IL-27/IL-10/inducible costimulator ligand. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 134: 944–954.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]