Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol analogs (PIAs) were originally designed to bind competitively to the Akt PH domain and prevent membrane translocation and activation. D-3-deoxydioctanoylphosphatidylinositol (D-3-deoxy-diC8PI), but not compounds with altered inositol stereochemistry (e.g., L-3-deoxy-diC8PI and L-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI), is cytotoxic. However, high resolution NMR field cycling relaxometry shows that both cytotoxic and non-toxic PIAs bind to the Akt1 PH domain at the site occupied by the cytotoxic alkylphospholipid perifosine. This suggests another mechanism for cytotoxicity must account for the difference in efficacy of the synthetic short-chain PIAs. In MCF-7 breast cancer cells, with little constitutively active Akt, D-3-deoxy-diC8PI (but not L-compounds) decreases viability concomitant with increased cleavage of PARP and caspase 9, indicative of apoptosis. D-3-deoxy-diC8PI also induces a decrease in endogenous levels of cyclins D1 and D3 and blocks downstream retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation. siRNA-mediated depletion of cyclin D1, but not cyclin D3, reduces MCF-7 cell proliferation. Thus, growth arrest and cytotoxicity induced by the soluble D-3-deoxy-diC8PI occur by a mechanism that involves downregulation of the D-type cyclin-pRb pathway independent of its interaction with Akt. This ability to downregulate D-type cyclins contributes, at least in part, to the anti-proliferative activity of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI and may be a common feature of other cytotoxic phospholipids.

Keywords: 3-deoxy-phosphatidylinositol, field-cycling NMR relaxometry, MCF-7 cells, D-type cyclin-retinoblastoma protein pathway

Graphical abstract

1.0 Introduction

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K1)/Akt pathway is critically involved in cell growth and survival [1] and is upregulated in a variety of human cancer cells lines and solid tumors [2, 3]. Cancer cells frequently attain constitutive Akt activity through several mechanisms such as amplification of PI3K or deletion of PTEN, a PI3K antagonist [4, 5]. Akt1 is activated by binding to PIP3, generated by PI3K, in the membrane, and once bound it is phosphorylated and primed to phosphorylate a diverse set of cellular targets [6-9]. Phosphatidylinositol analogs (PIAs) are amphiphilic molecules that were designed to bind competitively to the Akt PH domain in place of PIP3 and prevent Akt membrane translocation and subsequent activation [10]. Early versions of PIAs used long-chain phospholipids with poor solubility [11]; more recent versions of these compounds used single chain amphiphiles [12, 13]. These molecules have indeed been shown to be cytotoxic to a variety of cells [10]; their potency appears to correlate with particular Akt isoforms. In support of this, studies have reported the direct binding of PIAs to the PH domain of Akt1 [10, 14]. Thus, the anti-proliferative properties of several PIAs are thought to result, at least in part, from their competitive binding to the Akt PH domain in place of the natural activator PIP3 and preventing Akt translocation to the membrane, although more recent work has shown that alkylphospholipids alter lipid rafts in a way that leads to ceramide production and vesicle shedding culminating in cell death [15].

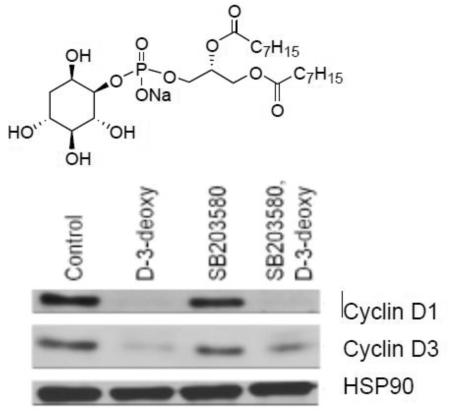

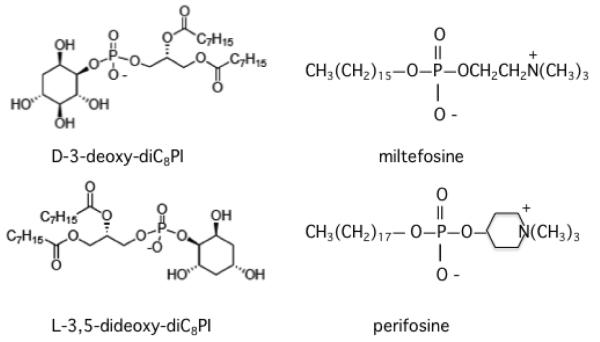

The small molecule D-3-deoxy-diC8PI was previously shown to inhibit proliferation of U937 human lymphoma cells [16]. The short acyl chains on the molecule were designed to improve the solubility of this PIA; the molecule also has a considerably higher CMC than longer chain PIAs and at low concentrations should not partition significantly into membranes. Similar short-chain PIAs with opposite inositol chirality, L-3-deoxy-diC8PI and L-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI, were not cytotoxic, consistent with specific interactions of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI with one or more target proteins [16]. Structures of these two PIAs are shown in Figure 1. In this work, we sought a more molecular view of the mechanism underlying the anti-proliferative activity of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI. Two types of approaches were used: (i) high resolution field cycling NMR relaxometry studies to explore the binding of short-chain PIAs to a recombinant PH domain of Akt1, and (ii) characterization of changes in cell cycle regulatory pathways induced in the MCF-7 cells by D-3-deoxy-diC8PI. We show both cytotoxic and nontoxic diC8PI compounds bind to the PH domain at a site discrete from where the activator, PIP3, binds. This site is also where alkylphospholipids such as miltefosine and perifosine (also in Figure 1) bind [17]). This strongly suggests that while direct interaction with Akt may occur, it is not likely to be the cause underlying the selective cytotoxicity of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI.

Figure 1.

Structure of the two diC8PI PIAs and two cytotoxic alkylphospholipids used in this work.

In exploring the mechanisms underlying the cytotoxicity of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI, we found that it reduces proliferation and viability in the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 under conditions where Akt is not activated. Inhibition of proliferation of these cells appears to result from downregulation of endogenous levels of cyclins D1 and D3 and a corresponding decrease in retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation similar to what is observed for MCF-7 cells treated with the soluble polar molecule phosphoethanolamine [18]. Consistent with this, depletion of cyclins D1 by siRNA reduces cell proliferation, as does the addition of specific CDK inhibitors. The reduction in MCF-7 cell viability by D-3-deoxy-diC8PI appears to result from apoptosis, as evidenced by cleavage of PARP and caspase 9. These results suggest that the ability to downregulate D-type cyclins contributes, at least in part, to the anti-proliferative activity of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI and may be a common feature of PIAs and zwitterionic alkylphospholipids.

2.0 Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals and reagents

L-glutamine, D-glucose, lysozyme, Tris base, and 0.1% poly-L-lysine solution were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. D-3-deoxy-diC8PI and L-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI were synthesized as described previously [16]. Different protein kinase inhibitors were purchased from EMD Millipore. These included the CDK2 inhibitor I, Tat-LFG (inhibitory peptide corresponding to YGRKKRRQRRRGPVKRRLFG), CDK2 inhibitor III or CVT-313 (2(bis-(hydroxyethyl)amino)-6-(4-methoxybenzylamino)-9-isopropyl-purine), and the CDK4/6 inhibitor CINK4 (trans-4-((6-(ethylamino)-2-((1-(phenylmethyl)-1H-indol-5-yl)amino)-4-pyrimidinyl)amino)-cyclohexanol. The FITC-BrdU flow cytometry assay kit was purchased from BD Pharmingen. Tissue culture media were purchased from Mediatech. Heat inactivated bovine fetal calf serum was purchased from Hyclone. All antibodies were acquired from Cell Signaling except that for cyclin D1 which was purchased from Fisher Scientific. Secondary goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. ECL reagents were purchased from KPL. Ontarget plus SMARTpool CREB1 siRNA, SMARTpool cyclin D1 siRNA, siGENOME cyclin D3 siRNA and siGENOME Control siRNA #3 were purchased from Dharmacon. Lipofectamine RNAimax was acquired from Invitrogen. Alamar Blue solution was purchased from AbD Serotec.

2.2 Overexpression, purification, and spin-labeling of the Akt1 His6-PH domain

An N-terminal hexa-His-tagged Akt1 PH domain (residues 1-131) protein was generated and purified as described previously [17]. For NMR experiments, the protein was spin-labeled with (1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-Δ3-pyrroline-3-methyl)methanethiosulfonate. Protein was first incubated with an excess of DTT to ensure reduction of the two cysteine residues, Cys60 and Cys77, in the protein. Several spin columns were used to remove excess reducing reagent, after which the protein was mixed with a 10-fold molar excess of spin-label for 3 h. Another spin column was used to remove the unreacted spin label. An aliquot of this protein preparation (concentration was measured with the BCA protein assay from BioRad) in 20 mM HEPES, 125 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, was mixed with either 3 mM D-3-deoxy-diC8PI, or 2 mM L-3,5-diC8PI. The sample was sealed in a 3.5″ long 5 mm NMR tube that was then attached to the sample shuttle of the field cycling apparatus.

2.3 High resolution field cycling 31P NMR

The binding of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI and L-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI to recombinant PH domain was assessed by measuring the 31P spin-lattice relaxation rate R1 (the inverse of the spin-lattice relaxation time) of the different compounds as a function of magnetic field strength (11.7 down to 0.02 T) using the Redfield high resolution field cycling instrument designed to be attached to a conventional 500 MHz NMR spectrometer [19]. The apparatus uses a mechanical system to move the NMR sample, after the spins have been polarized in the probe, to defined positions in the bore of the magnet where it now relaxes at the lower field. After a variable time, the sample is rapidly moved back into the probe and the remaining magnetization monitored. This shuttling experiment provides R1 for the 31P in a given sample over a wide range of magnetic fields. If a nucleus in the sample is sensing two or more different environments, for example free and protein bound, the observed R1 at a given field will be an average. The ability to cover a very wide range of magnetic fields allows one to separate relaxation mechanisms (dipolar versus chemical shift anisotropy, CSA, relaxation) and also to monitor motions of a ligand that occur on different time-scales (for example, fast internal motions within a molecule and overall molecule or aggregate rotation). Dipolar relaxation is particularly useful, since it can supply distances of the 31P to its relaxer protons. For 31P in an ester linkage, the protons three bonds away provide an intramolecular dipolar pathway for relaxation. However, introduction of a much larger dipole, e.g., the unpaired electron of a stable spin-label, can supply a much more efficient pathway for dipolar relaxation, if the label is close enough. For biological phosphates that form aggregates (micelles or bilayers), dipolar interactions provide the major relaxation pathway below 2 T (for comparison the field of a 500 MHz spectrometer is 11.74 T).

When the field dependence R1 profile for the 31P in the molecule of interest is measured using a spin-labeled protein and then compared to that for an unlabeled protein (at the same concentration), the specific relaxation enhancement due to proximity to the spin-label, ΔR1 = R1(spin-labeled protein) – R1(unlabeled protein), can be obtained [17, 20, 21]. To quantify this paramagnetic relaxation enhancement of R1, or PR1E, the field dependence profile of this difference in R1 at each field is fit to the following expression:

| Eq. 1 |

where the parameter ω, the angular frequency of the 31P in rad s−1, is the magnetic field in Tesla times the gyromagnetic ratio of 31P, and c is a small rate enhancement from faster dipolar motions or a small cross-relaxation term between the dipolar interaction and CSA relaxation. CSA is responsible for the increase in R1 above 6 T for nearly all phosphorylated molecules; it is caused by fast fluctuations of the P-O bonds that alter the symmetry around the 31P. CSA is not affected by the relatively distant unpaired electron.

A PR1E that represents binding of a lipid ligand to a specific site on the protein requires that the lipid occupy that site for at least the rotational correlation time of the entire protein-micelle complex. The key extracted parameters that provide estimates of the 31P-to-electron distance are RP-e(0), the maximum relaxation rate (in s−1) of the 31P caused by proximity to the unpaired electrons on the protein (R1 extrapolated to zero magnetic field), and τP-e, the correlation time that describes this interaction. For the PIA amphiphiles binding to the Akt1 PH domain, a correlation time >20 ns range is longer than expected for this small protein and would be consistent with overall protein/micelle tumbling. Lipids in the micelle that do not stay in a site on this time scale will have very little contribution to the PR1E measured at low fields where such interactions are detected (i.e., below 1 T).

The distance of a ligand 31P from the unpaired electron of the spin-label on the protein is estimated by the following:

| Eq. 2 |

where μo is the permeability of free space (10−7 in S.I. units), h is Planck’s constant, γP and γH are the phosphorus and proton gyromagnetic ratios, [PH] is the concentration of the PH domain and [Lo] is the concentration of the ligand. Since r6 is proportional to τP-e/RP-e(0), small changes in distance lead to easily observed changes in RP-e(0). The complication in this system is that the Akt1 PH domain has two cysteine residues, Cys60 and Cys77, that are both spin-labeled [17]. The spin-label on Cys77 is significantly closer to the PI(3,4,5)P3 phosphodiester 31P and even closer to the novel alkylphospholipid site on the PH domain that we described previously [17]. Therefore, the spin-label on Cys77 is likely to provide most of the PR1E and dominate the distance calculated (indicated as rapp for the apparent rP-e distance). If the two phospholipids bind to the same site, even if the protein has more than one spin-label attached, they will have similar field dependence profiles and r6app will be the same. Amphiphiles, even if structurally similar, could form different size aggregates that will alter τ. If they bind to the same site, RP-e(0) will change as well because rapp6 is proportional to τP-e/RP-e(0). Differences in protein or ligand concentrations can also be taken into account with Eq. 2. Therefore, τP-e/RP-e(0) and the estimated rapp are what we use to directly compare how different ligands bind to the isolated Akt1 PH domain [17].

2.4 Mammalian cell culture and cytotoxicity assays

The MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line, purchased from the ATCC, was maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 95% humidity. MCF-7 cells were cultured in Eagle’s MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 0.01 mg/mL bovine insulin and 1 μl/mL Mycozap CL. MCF-7 cells (30,000) were plated in each well of a 96-well plate and allowed to adhere overnight. The following day, the tissue culture medium was replaced with 180 μL of fresh complete or serum free medium containing various concentrations of test compounds. The cells were incubated for 20 h prior to adding 20 μL Alamar Blue to each well and incubating for an additional 4 h. The fluorescence of the reduced Alamar Blue, which is proportional to the number of living cells, was read by excitation at 560 nm and emission at 590 nm on a Molecular Devices Spectromax M5 Plate Reader. Data were normalized to the control fluorescence and plotted as a viability curve in order to determine the IC50 of the compound.

For evaluating the effect of protein kinase inhibitors on the cells, the MCF-7 cells (~10,000 per well) adhering to a 96-well plate had the medium replaced with fresh medium containing the specified protein kinase inhibitors. Each inhibitor was tested at four concentrations with 3 replicates per concentration. Cells were incubated for 24 h, at which point the Alamar Blue was added and the cells incubated for 4 h prior to measuring the fluorescence. The fluorescence reported for a given concentration of an inhibitor(s) was an average of three wells, normalized to the average of the control wells, and plotted against the log of the concentration of the inhibitors.

2.5 BrdU incorporation assays

MCF-7 cells were incubated without serum and with or without D-3-deoxy diC8PI for 24 h in a 6 well plate. After 24 h, BrdU at a final concentration of 10 μM was added to each well and incubated for an additional 8 h. The cells were then trypsinized, collected by centrifugation, washed with ice-cold PBS, and then washed with BD Perm/Wash buffer and fixed with BD Cytoperm Permeabilization Buffer Plus. The cells were incubated with 30 μg DNAse in Dulbecco’s PBS for 1 h at 37°C to expose the incorporated BrdU. After washing, the cells were stained with FITC conjugated anti-BrdU antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCanto Flow Cytometer.

2.6 Western blots

Cells were incubated in ice cold TBS-T containing 10 μl/mL protease inhibitor cocktail, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 100 nM okadaic acid, and 1 mM DTT. After 10 min, the cells were subjected to a single freeze-thawed cycle on dry ice. Lysates were pre-cleared by centrifugation at 16,000xg, 4°C. Solubilized proteins (20 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was then transferred onto a 0.2 μm PVDF membrane and then the membrane blocked with 5% w/v non-fat dry milk in TBS-T. The membrane was then incubated overnight at 4°C with 1:1000 primary antibody. The membrane was washed 3 times in TBS-T and incubated with anti-rabbit or -mouse HRP-conjugated antibody (1:2500 dilution) for 1 h. The blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence.

2.7 Transfection of siRNA

For siRNA transfections, 12 pmol siRNA was mixed with 190 μL OptiMem medium in individual wells of a 96-well. Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (1.9 μL) was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. MCF-7 cells were trypsinized and transferred into medium devoid of antibiotics. The cells were diluted to a density of 100,000 cells/mL, and 95,000 cells were plated in each well. After 48 h, the cells were transferred into fresh media containing antibiotics. The siRNAs used to deplete endogenous cyclin D1 or cyclin D3 are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

siRNA sequences used to reduce levels of cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 in MCF-7 cells.

| Target | Specific sequence |

|---|---|

| siGENOME CCND3 | GAUCGAAGCUGCACUCAGG |

| SMARTpool ON- TARGET plus CCND1 |

ACAACUUCCUGUCCUACUA, GUUCGUGGCCUCUAAGAUG, GCAUGUAGUCACUUUAUAA, GCGUGUAGCUAUGGAAGUU |

3.0 Results

3.1 D-3-deoxy-diC8PI and L-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI bind to the Akt PH domain at a site distinct from that for diC8PI(3,4,5)P3

Our high resolution field cycling work with the alkylphospholipids miltefosine and perifosine showed that there is a discrete site on the Akt1 PH domain for these cytotoxic alkylphospholipids that is not occupied by PIP3 [17]. Occupation of this site, near but distinct from the phosphoinositide binding site, would misorient the PH domain on membranes, an event likely to weaken association of Akt1 with its target membrane. Furthermore, while miltefosine can also bind in the PIP3 site, it is easily displaced by small amounts of diC8PIP3. Perifosine, with a larger aminoalcohol headgroup does not bind to the PIP3 site. These results strongly suggested that if interactions of alkylphospholipids with Akt1 lead to cytotoxicity, it is this secondary site that is critical [17]. Field cycling relaxometry was used to determine where the two short-chain deoxy-PI compounds bind on the PH domain – at the primary alkylphospholipid site or in the PIP3 site.

At the concentration of dioctanoyl-PI compounds needed for the NMR PR1E experiments (low mM), they form small micelles [16]. Micelles are quite dynamic entities with rapid exchange of monomers into micelles and fast lateral movements of individual amphiphiles within a micelle. The basic premise for the 31P NMR experiments is that if a given molecule binds moderately tightly to a specific site on a spin-labeled protein, its 31P will experience relaxation by any nearby spin-labels. By examining the relaxation rates at low fields and moderately high ratios of lipid to protein (>80:1 where at most there is likely to be a single protein associated with a micelle), we can isolate interactions that occur on a longer time scale (in these systems the longest is the rotational correlation time for the protein/phospholipid micelles). Molecules moving rapidly within and in and out of the micelles will not experience significant relaxation by the spin-labeled protein since a given molecule will not persist in a discrete amphiphile/protein complex over that time scale. However, an amphiphile bound to the PH domain for at least that period of time will be efficiently relaxed by the spin-label. The measured PR1E depends on the magnetic field strength, and the correlation time is easily assessed from the field dependence profile using Eq. 1. This methodology has been applied to phospholipids in vesicles binding to discrete sites on spin-labeled proteins [20, 21] and to different short-chain phospholipids in micelles binding to spin-labeled PTEN [22].

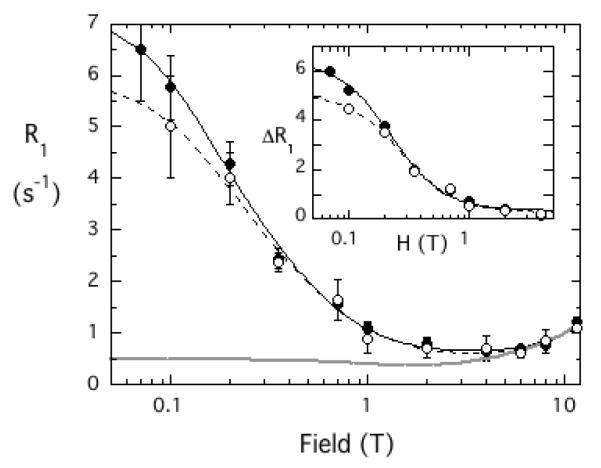

The short chain PIAs form relatively small micelles. In the absence of protein the 31P R1 field dependence is equivalent to the gray line on Figure 2. If one looks carefully there is a minimum in R1 between 1 and 2 T. The rise as the field is lowered (dipolar relaxation) is consistent with small micelles and a correlation time of ~ 2 ns [16]. Adding 37 μM unlabeled protein has no significant effect on this profile. However, when spin-labeled Akt1 PH domain is added, there is a very large increase in R1 as the field is decreased below 1 T. The correlation time for the PIAs interacting with the spin-labeled protein is also much longer (30-40 ns) than for the micelles by themselves (~ 2 ns). Thus, the complex of protein and PIA is a considerably larger aggregate. The plots of the field dependence of 31P R1 for the two PIA compounds interacting with the spin-labeled Akt1 PH domain are quite similar. However, the concentrations of the amphiphiles were different in the experiments: 2 mM L-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI versus 3 mM D-3-deoxy-diC8PI. From Eq. 2, the difference in [PH]/[Lo] will lead to a τP-e/RP-e(0) that is larger for the L-compound, which indicates a slightly longer rapp.

Figure 2.

Field dependence of 31P R1 for deoxy-diC8PI compounds binding to the spin-labeled Akt1 PH domain: (●) 3 mM D-3-deoxy diC8PI or ( ) 2 mM L-3,5-dideoxy diC8PI in the presence of 37 μM spin-labeled Akt1-PH compared to the control for either short-chain PI alone (solid gray line). The inset shows the difference in relaxation rate, ΔR1, as a function of magnetic field after subtraction of the control.

) 2 mM L-3,5-dideoxy diC8PI in the presence of 37 μM spin-labeled Akt1-PH compared to the control for either short-chain PI alone (solid gray line). The inset shows the difference in relaxation rate, ΔR1, as a function of magnetic field after subtraction of the control.

As shown in Table 2, the rapp6 value extracted from fitting these data is 50% larger for L-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI, indicating a longer distance of the 31P from the two spin labels on the Akt1 PH domain. The rapp values for the two PIAs, 10.1±0.1 and 10.8±0.2 Å, for D-3-deoxy-diC8PI and L-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI, respectively, are very close to the values for the two alkylphospholipids (9.7±0.2 Å for miltefosine and 10.8±0.2 Å for perifosine [17]). Both short-chain PIAs have rapp values shorter than what was estimated for diC8PIP3 (rapp = 15.2±0.8 Å [17]), which binds only in a single very cationic site further away from the two spin-labeled cysteines. Hence, both short-chain PIAs bind to the novel alkylphospholipid site on the Akt1 PH domain. The previous study also showed that miltefosine could bind to the PIP3 site (as well as the novel site) but was easily displaced by low concentrations of a PIP3 ligand. In contrast, perifosine only occupied the novel amphiphile site on the PH domain. With the spin-labeled protein, this translates to a slightly shorter rapp distance for miltefosine (the paramagnetic relaxation of the miltefosine bound in the PIP3 site contributes much less than that for the miltefosine in the novel site since it is further from the spin-labels and the PR1E depends on r−6). With the PIAs, the NMR experiments indicate that the L- compound, like perifosine cannot occupy the PIP3 site, while the D-3-deoxy-diC8PI may access both sites. That the rapp for D-3-deoxy-diC8PI is slightly longer than the value for miltefosine suggests that its binding is either (i) altered so that the 31P of this PIA is further away from the spin-label compared to the phosphate moiety of miltefosine, or (ii) weaker than miltefosine and the site is not saturated under the experimental conditions used. While the inositol stereochemistry is that of the natural ligand, PIP3, D-3-deoxy-diC8PI lacks the three phosphates on the ring that are critical for tight PIP3 binding; it also has two acyl chains whereas miltefosine has a single longer chain which could influence the binding [17]).

Table 2.

Parameters extracted from high resolution field-cycling 31P NMR relaxometry data for the binding of deoxyphosphatidylinositols, cytotoxic alkylphospholipids, and diC8PIP3 to the spin-labeled Akt1 PH domain (37 μM).

| Ligand | (mM) | τP-e (ns) |

RP-e(0) (s−1) |

rapp6 (m6) |

rappa (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-3-deoxy diC8PI | 3 | 41±3 | 6.08±0.22 | 1.01×10−54 | 10.1±0.1 |

| L-3,5-dideoxy- diC8PI |

2 | 33±4 | 4.80±0.29 | 1.56×10−54 | 10.8±0.2 |

| miltefosine b | 0.83×10−54 | 9.7±0.2 | |||

| perifosine b | 1.41×10−54 | 10.6±0.7 | |||

| diC8PIP3 (P-1) b | 12.4×10−54 | 15.2±0.8 |

The rapp reflects for the averaged distance of the 31P from the two spin-labels (although it is dominated by the nitroxide on Cys77).

The field cycling parameters are from [17]. For diC8PIP3, only P-1, the phosphodiester nucleus, is reported for comparison to the phosphodiester 31P of the PIAs.

If alkylphospholipid occupation of the novel binding site on Akt1, and not the diC8PIP3 site, is responsible for its cytotoxicity, then it is unlikely that binding of either of the 3-deoxy-diC8PI compounds to the Akt1 PH domain is responsible for the cell death that is preferentially observed with D-3-deoxy-diC8PI but not the L-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI [16]. Other pathways and protein(s) must be targeted by these short-chain PIAs.

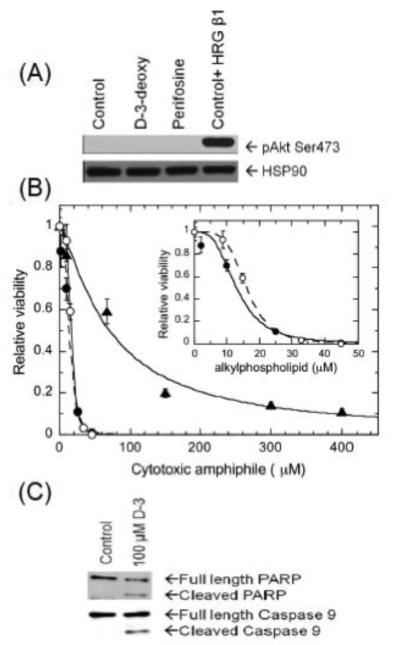

3.2 D-3-deoxy-diC8PI is cytotoxic to human MCF-7 breast cancer cells

To further investigate the mechanism underlying D-3-deoxy-diC8PI-mediated cell death, we selected human MCF-7 cells because they do not exhibit appreciable levels of Akt phosphorylation in the absence of growth factors [23]. The MCF-7 cells then serve as a model cell line to assess the effects of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI on viability in the absence of Akt activation. These cells also have the advantage that the effects of a given compound can be measured for cells incubated in fresh or serum-depleted medium.

Akt phosphorylation on the activation residue Ser473 was not detected in MCF-7 cells (Figure 3A); treatment with either D-3-deoxy-diC8PI or perifosine had no discernable effect on Akt phosphorylation status. As a control, treatment of MCF-7 cells with HRG β1 increased Akt phosphorylation on Ser473. Figure 3B shows the dose response of MCF-7 cells treated with D-3-deoxy-diC8PI at concentrations ranging from 0 to 400 μM. D-3-deoxy-diC8PI decreased cell viability with an IC50 = 79±11 μM when measured at 24 h. Western blot analysis of whole cell detergent lysates from parallel MCF-7 cells cultured with D-3-deoxy-diC8PI revealed cleavage of caspase 9 (3.5 h) and PARP (6.5 h) (Figure 3C). These results indicate that D-3-deoxy-diC8PI decreases cell viability via inducing an apoptotic pathway in MCF-7 cells incubated in the absence of growth factors.

Figure 3.

Treatment of serum-starved MCF-7 cells, which have very low constitutive phosphorylated Akt, with D-3-deoxy diC8PI induces aoptosis. (A) Akt phosphorylation on Ser473 (pAkt Ser473) was measured in whole MCF-7 cell detergent lysates by western blot analysis. The blot was stripped and subsequently probed for constitutive expression of HSP90. The serum-starved MCF-7 cells were incubated with PBS (control), 100 μM D-3-deoxy-diC8PI (D-3-deoxy), or 16 μM perifosine for 3.5 h. As a positive phosphorylation control, cells were incubated with PBS without serum for 3 h 10 min and then stimulated with 100 ng/mL HRG β1 for 20 min. (B) Viability curves for cells treated with D-3-deoxy diC8PI (▴ ) or the alkylphospholipids miltefosine (●) and perifosine ( ) for 24 h in the absence of serum. The inset shows the viability data for the two alkylphospholipids. (C) D-3-deoxy diC8PI induces apoptosis in MCF-7 cells as evidenced by PARP cleavage after 6.5 h and caspase 9 cleavage after 3.5 h incubation.

) for 24 h in the absence of serum. The inset shows the viability data for the two alkylphospholipids. (C) D-3-deoxy diC8PI induces apoptosis in MCF-7 cells as evidenced by PARP cleavage after 6.5 h and caspase 9 cleavage after 3.5 h incubation.

3.3 D-3-deoxy-diC8PI induces CREB hyperphosphorylation by activation of p38 MAPK

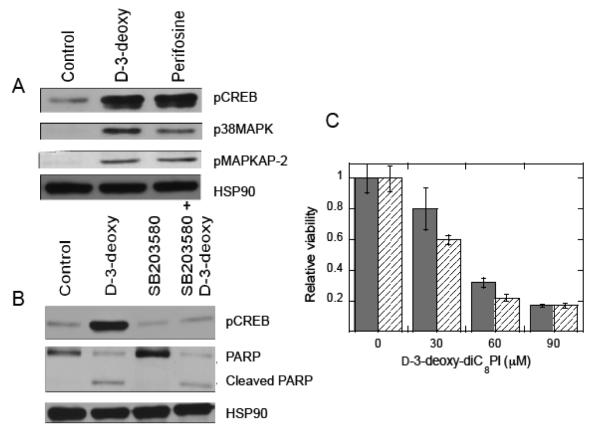

A more detailed study of the effects of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI on MCF-7 cells was undertaken to provide insight into how it triggers cell death. Perfosine, previously studied for its effect on MCF-7 cells, was also examined for comparison [24]. Components of the p38 MAPK pathway were activated in MCF-7 cells following treatment with D-3-deoxy-diC8PI (Figure 4A), as evidenced by increased phosphorylation of p38 MAPK on the activation residues Thr180/Tyr183 and phosphorylation of the p38 MAPK substrate, MAPKAPK-2 on the activation residue Thr222. Similar results were obtained following treatment of MCF-7 cells with perifosine. D-3-deoxy-diC8PI also increased phosphorylation of the cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB) on Ser133, a downstream target of p38 MAPK. p38 MAP kinases are activated by a variety of cellular stresses including osmotic shock and inflammatory cytokines, and they are involved in cell differentiation, apoptosis and autophagy. However, p38 MAPK activity does not appear to be required for D-3-deoxy-diC8PI-mediated apoptosis in serum-starved MCF-7 cells, since blocking kinase activity with the p38 MAPK inhibitor, SB203580, prior to D-3-deoxy-diC8PI addition does not block PARP cleavage (Figure 4B) nor protect MCF-7 cells from D-3-deoxy-diC8PI-induced cell death (Figure 4C). In these viability assays DMSO was used to solubilize the p38 MAPK inhibitor. Interestingly, addition of the DMSO alone has a small effect on the cells, slightly reducing the IC50 of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI to ~40 μM.

Figure 4.

Changes in phosphorylation of key proteins in serum-starved MCF-7 cells show that treatment with D-3-deoxy diC8PI leads to activation of the p38 MAPK pathway. (A) Incubation of MCF-7 cells with 100 μM D-3-deoxy-diC8PI (D-3-deoxy) or 16 μM perifosine in the absence of serum for 3..5 h led to phosphorylation of p38MAPK on Thr180/Thr182, pMAPKAPK-2 on Thr222 and hyperphosphorylation of pCREB on Ser133. (B) Cells were treated with DMSO or 10 μM SB203580, a MAPK inhibitor, for 1 h prior to incubation with 100 μM of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI (3.5 h for pCREB and 6.5 h for PARP). The presence of SB203580 eliminates CREB hyperphosphorylation but not PARP cleavage induced by D-3-deoxy-diC8PI. (C) Cells were treated with DMSO (solid grey) or 10 μM SB203580 (hatched) in serum free media for 6 h prior to 24 h incubation with various concentrations of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI.

3.4 D-3-deoxy-diC8PI effects on D-type cyclin expression and retinoblastoma phosphorylation

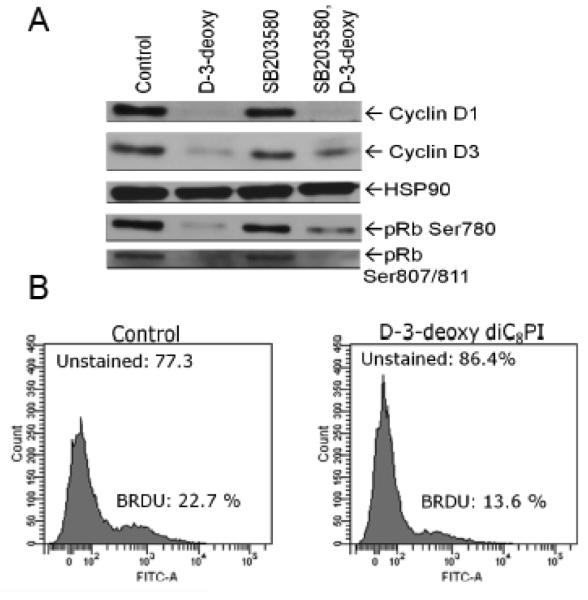

Numerous studies in tumor model systems have revealed that downregulation of D-type cyclin expression occurs in response to inhibitors of Akt activity and mTOR, and this contributes to cell cycle arrest [25]. Perifosine also induces cell cycle arrest in several cell lines [24]. D-type cyclins are regulatory partners required for cyclin dependence kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) activities that play a critical role in G1-to-S phase progression in mammalian cells [26]. Human MCF-7 cells predominantly express cyclins D1 and D3 [27]. Treatment of MCF-7 cells with D-3-deoxy-diC8PI decreased the levels of endogenous cyclins D1 and D3 in comparison to control non-treated MCF-7 cells (Figure 5A). D-type cyclin-CDK4/6 holoenzymes phosphorylate the retinoblastoma protein contributing to its inactivation [25, 26]. To determine if decreased D-type cyclin expression prevented phosphorylation of pRb, we immunoblotted endogenous pRb with antibodies that detect phosphorylation on the CDK4/6- and CDK2-targeted sites Ser780 and Ser807/811, respectively. As shown in Figure 5A, phosphorylation of Rb on residues Ser780 and Ser807/811was decreased in response to D-3-deoxy-diC8PI. Consistent with these findings, D-3-deoxy-diC8PI reduced DNA synthesis in MCF-7 cells, as measured by BrdU incorporation (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

(A) Regulation of levels of cyclins D1 and D3 by D-3-deoxy-diC8PI. Cells were pretreated with DMSO (lanes 1 and 2) or 10 μM SB203580 (lanes 3 and 4) for 1 h prior to incubation with PBS (lanes 1 and 3) or 100 μM D-3-deoxy-diC8PI for 3.5 h. Detergent whole cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by western blot analysis for cyclin D1 and D3 and phosphorylation of pRb on Ser780 and Ser807/811. The blot was stripped and probed for constitutive expression of HSP90. (B) D-3-deoxy diC8PI inhibits DNA synthesis.

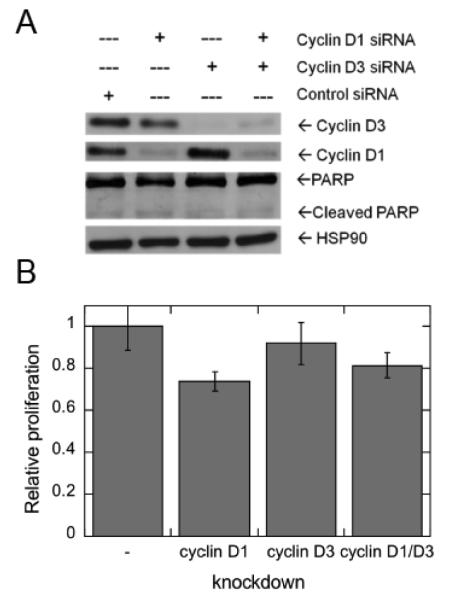

In control studies, the contribution of D-type cyclin expression to MCF-7 cell proliferation was evaluated using siRNA-mediated depletion of cyclins D1 and/or cyclin D3 (Figure 6A). Depletion of cyclin D1 leads to a statistically significant decrease in MCF-7 cell proliferation, whereas depletion of cyclin D3 had no measurable effect (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Effects of siRNA-mediated depletion of D-type cyclins on MCF-7 cell proliferation. (A) MCF-7 cells were incubated with the indicated siRNAs for 48 h. The expression of endogenous cyclins D1 and D3 were determined by western blot analysis. The blot was stripped and probed for constitutive expression of HSP90. (B) Parallel MCF-7 cells were evaluated for proliferation.

3.5 CDK and p38 MAPK inhibitors mimic D-3-deoxy-diC8PI effects

The results in Figure 5 indicate that D-3-deoxy-diC8PI reduces phosphorylation of pRb on both CDK4/6- and CDK2-targeted serine residues. To evaluate the role of CDK4/6 together with CDK2 in MCF-7 cell proliferation, several inhibitors of these kinases were examined alone and in combinations. IC50 values were determined for the individual inhibitors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of CDK and MAPK inhibitors on MCF-7 cells.

| Inhibitor | Target | IC50

a (μM) |

Relative viability (μM inhibitors) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| ML3403 | p38 MAPK | 37.0±2.5 | 0.30 (50) |

| Tat-LFG | CDK2 | - b | 1.00 (50) |

| CVT-313 | CDK2 | 8.8±3.0 | 0.98 (1) |

| 0.81 (2.5) | |||

| CINK4 | CDK4/6 | 15.6±1.2 | 0.90 (5) |

| 0.76 (10) | |||

| ML3403 + CVT-313 | p38 MAPK / CDK2 | 0.31 (50/2.5) | |

| ML3403 + CINK4 | p38 MAPK / CDK4/6 | 0.17 (50/10) | |

| Tat-LFG + CINK4 | CDK2 / CDK4/6 | 0.76 (5/10) | |

| CVT-313 + CINK4 | CDK2 / CDK4/6 | 0.53 (1/5) | |

| 0.35 (2.5/10) | |||

Evaluated only for single inhibitors.

Up to 1 mM of this CDK2 inhibitor was incubated with cells with no significant effect on cell viability.

With the exception of Tat-LFG, which showed little cytotoxicity up to mM concentrations of the peptide, combinations of inhibitors were much more effective than the individual inhibitors. For example, cells in the presence of 1 μM CDK2 inhibitor CVT-313 or 5 μM CDK4/6 inhibitor CINK4 were 98% and 90% as viable as control cells. However, for cells in the presence of 1 μM CVT-313 and 5 μM CINK4, cell viability was reduced to 53%, indicating a synergistic response to inhibiting both kinases. Whatever the details of the pathway, a major contributor to the cytotoxicity of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI in MCF-7 cells, appears to involve reduction of more than one D-type cyclin.

4.0 Discussion and Conclusions

PIAs were originally developed to inhibit Akt activity by binding to the PH domain of Akt and preventing its translocation to the membrane. Their use as anticancer agents has been explored in part because many cancer cells display dysregulated PI3K/Akt signaling [28]. PIAs are broadly cytotoxic in cancer cells with constitutively active Akt, where they induce apoptosis [29, 30]. However, accumulating evidence indicates that PIAs and the related alkylphospholipids have other cellular targets in addition to Akt. Independent of Akt they have been shown to activate p38α [31] These types of compounds partition into cell membranes and can also disrupt lipid rafts. At early time points in incubating these PIAs with cells, nanovesicle shedding is observed and is promoted by ceramide generation [15]. However, this effect was produced with moderately high concentrations of the PIAs (100 μM). The alkylphospholipid perifosine is shown to block the cell cycle [24]. That cell cycle arrest is also observed with D-deoxy-diC8PI and implies this compound, like other PIAs and alkylphospholipids, has multiple effects. Furthermore, the induction of apoptosis is independent of p38 MAPK activity since inhibition of p38 MAPK activity in MCF-7 cells did not prevent or retard D-3-deoxy-diC8PI-mediated cell death. For this class of compounds there must be specific protein targets since D-3-deoxy-diC8PI is cytotoxic but the L-isomer and related L-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI are not [16].

D-type cyclins are key regulators of cell cycle progression and are unique because their expression is induced by signals from extracellular mitogens, linking cell cycle regulation to the exogenous environment. They are expressed through the G1 phase of the cell cycle [32]. In the absence of such signals, the D-type cyclins are degraded by the 26 S proteasome, which prevents the cell from progressing from early G1 phase into late G1 and ultimately S phase [33]. However, in many breast cancers, the D-class cyclins are overexpressed, particularly cyclins D1 and D3 [34]. This promotes unrestricted progression through the cell cycle and tumorigenesis. There is significant redundancy between cyclins D1 and D3, as well as between D-type cyclins and cyclin E, which is expressed later in G1 phase [34, 35]. D-3-deoxy-diC8PI promotes the loss of cyclins D1 and D3 in MCF-7 cells. These results may be particularly relevant to the mechanism of cytotoxicity as phosphorylation of pRb was decreased in the presence of D-3-deoxy-diC8PI. While siRNA knockdown of cyclin D1 and/or cyclin D3 was not enough to induce apoptosis, the loss of cyclin D1 did significantly inhibit proliferation of MCF-7 cells. Together these results suggest that the soluble PIA D-3-deoxy-diC8PI has at least two targets that lead to both cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.

The work also shows the ability of high resolution field cycling relaxometry to probe where an amphiphile, in this case two synthetic phosphatidylinositol derivatives, binds on a spin-labeled protein. Experiments are run under conditions where there is a large excess of amphiphile, so that micelles without protein must occur along with the protein/amphiphile aggregate and rapid exchange of amphiphiles between micelles (and monomer) occurs. However, if there is a specific site for the amphiphile on the protein that is occupied for at least the rotational correlational time of the complex, then the τP-e for the protein/micelle complexes can be unambiguously extracted. For a given τP-e, the maximum relaxation rate is proportional to rP-e−6 and occupation of a site close to the spin-label will exhibit a large PR1E while those that place the 31P even a few Å further from a spin-label have a much smaller effect [17]. Errors in measuring RP-e(0) are typically under 10% so that this method serves as an excellent way to compare how and where phospholipids, detergents, or other amphiphiles bind to a protein.

Highlights.

NMR shows cytotoxic and non-toxic PIAs bind to the same Akt1 PH domain site.

MCF-7 cells exhibit reduced levels of constitutively active Akt.

D-3-deoxy-diC8PI induces apoptosis in MCF-7 cells.

D-3-deoxy-diC8PI downregulates the D-type cyclin-retinoblastoma protein pathway.

The effect of this PIA is independent of its interaction with Akt.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by N.I.H grant R01 GM60418 to M.F.R.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BrdU, 5-bromo-2'-deoxyuridine; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; CMC, critical micelle concentration; D-3-deoxy-diC8PI, D-3-deoxy-dioctanoylphosphatidylinositol; L-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI, L-3,5-dideoxy-dioctanoylphosphatidyinositol; D-diC8PIP3, D-dioctanoylphosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; DTT, dithiothreitol; PIA, phosphatidylinositol analog; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate; pRb, retinoblastoma protein; TBS-T, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, with 100 mM NaCl and 0.1% Triton X-100.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions: C. Gradziel, D. Jewel, F. Dufort performed experiments and analyzed data; the cell studies were supervised and interpreted by T. Chiles. P. Jordan synthesized the short-chain PIAs with the supervision of S. Miller. M. Roberts carried out field cycling relaxometry experiments and coordinated writing the manuscript.

References

- [1].Yao R, Cooper GM. Regulation of the Ras signaling pathway by GTPase-activating protein in PC12 cells. Science. 1995;267:2003–2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hennessy BT, Smith DL, Ram PT, Lu Y, Mills GB. Exploiting the PI3K/AKT pathway for cancer drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:988–1004. doi: 10.1038/nrd1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Leevers SJ, Vanhaesebroeck B, Waterfield MD. Signalling through phosphoinositide 3-kinases: the lipids take centre stage. Curr. Opin. Cell. 1999;11:219–225. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Vanhaesebroeck B, Leevers SJ, Panayotou G, Waterfield MD. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases: a conserved family of signal transducers. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1997;22:267–72. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Frech M, Andjelkovic M, Ingley E, Reddy KK, Flack JK, Hemmings BA. High affinity binding of inositol phosphates and phosphoinositides to the pleckstrin homology domain of RAC/protein kinase B and their influence on kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:8474–8481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].James SR, Downes CP, Gigg R, Grove SJA, Holmes AB, Alessi DR. Specific binding of the Akt-1 protein kinase to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate without subsequent activation. Biochem. J. 1996;315:709–713. doi: 10.1042/bj3150709. Biol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Downward J. Mechanisms and consequences of activation of protein kinase B/Akt. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 1998;10:262–267. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80149-x. (1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bellacosa A, Chan TO, Ahmed NN, Datta K, Malstrom S, Stokoe D, McCormick F, Feng J, Tsichlis P. Akt activation by growth factors is a multiple step process: the role of the PH domain. Oncogene. 1988;17:313–325. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gills JJ, Dennis PA. The development of phosphatidylinositol ether lipid analogues as inhibitors of the serine/threonine kinase, Akt. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2004;13:787–797. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.7.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kozikowski AP, Kiddle JJ, Frew T, Berggren M, Powis G. Synthesis and biology of 1D-3-deoxyphosphatidylinositol: a putative antimetabolite of phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate and an inhibitor of cancer cell colony formation. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:1053–1056. doi: 10.1021/jm00007a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kozikowski AP, Sun H, Brognard J, Dennis PA. Novel PI analogues selectively block activation of the pro-survival serine/threonine kinase Akt. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1144–1145. doi: 10.1021/ja0285159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Meuillet EJ, Mahadevan D, Vankayalapati H, Berggren M, Williams R, Coon A, Kozikowski AP, Powis G. Specific inhibition of the Akt1 pleckstrin homology domain by D-3-deoxy-phosphatidyl-myo-inositol analogues. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2003;2:389–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cheng JQ, Lindsley CW, Cheng GZ, Yang H, Nicosia SV. The Akt/PKB pathway: molecular target for cancer drug discovery. Oncogene. 2005;24:7482–7492. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gills JJ, Zhang C, Abu-Asab MS, Castillo SS, Marceau C, LoPiccolo J, Kozikowski AP, Tsokos M, Goldkorn T, Dennis PA. Ceramide mediates nanovesicle shedding and cell death in response to phosphatidylinositol ether lipid analogs and perifosine. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e340. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang YK, Chen W, Blair D, Pu M, Xu M,Y, Miller SJ, Redfield AG, Chiles TC, Roberts MF. Insights into the structural specificity of the cytotoxicity of 3-deoxyphosphatdiylinositols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7746–7755. doi: 10.1021/ja710348r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gradziel CS, Wang Y, Stec B, Redfield AG, Roberts MF. Cytotoxic amphiphiles and phosphoinositides bind to two discrete sites on the Akt1 PH domain. Biochemistry. 2014;53:462–472. doi: 10.1021/bi401720v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ferreira AK, Meneguelo R, Pereira A, Mendonca O, Filho R, Chierice GO, Maria DA. Synthetic phosphoethanolamine induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells through the mitochondrial pathway. Biomed. Pharm. 2013;67:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Redfield AG. High-resolution NMR field-cycling device for full-range relaxation and structural studies of biopolymers on a shared commercial instrument. J. Biomol. NMR. 2012;52:159–177. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9594-1. (2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pu M, Orr A, Redfield AG, Roberts MF. Defining specific lipid-binding sites for a peripheral membrane protein in situ using sub-tesla field-cycling NMR. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:26916–26922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cai J, Guo S, Lomasney JW, Roberts MF. Ca2+-independent binding of anionic phospholipids by phospholipase C δ1 EF-hand domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:37277–37288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.512186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wei Y, Stec B, Redfield AG, Weerapana E, Roberts MF. Phospholipid-binding sites of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN): exploring the mechanism of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:1592–1606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.588590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yi YW, Kang HJ, Kim HJ, Hwang JS, Wang A, Bae I. Inhibition of constitutively activated phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway enhances antitumor activity of chemotherapeutic agents in breast cancer susceptibility gene 1-defective breast cancer cells. Mol. Carcinog. 2013;52:667–675. doi: 10.1002/mc.21905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Celeghini C, Voltan R, Rimondi E, Gattei V, Zauli G. Perifosine generated apoptosis and cell cycle block at G2M checkpoint. Invest. New Drugs. 2011;29:392–395. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Basso AD, Solit DB, Munster PN, Rosen N. Ansamycin antibiotics inhibit Akt1 activation and cyclin D expression in breast cancer cells that overexpress HER2. Oncogene. 2002;21:1159–1166. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Alao JP. The regulation of cyclin D1 degradation: roles in cancer development and the potential for therapeutic invention. Mol. Cancer. 2007;6:24–40. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Evron E, Umbricht CB, Korz D, Raman V, Loeb DM, Niranjan B, Buluwela L, Weitzman SA, Marks J, Sukumar S. Loss of cyclin D2 expression in the majority of breast cancers is associated with promoter hypermethylation. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2782–2787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Qiao L, Nan F, Kunkel M, Gallegos A, Powis G, Kozikowski AP. 3-Deoxy-D-myoinositol 1-phosphate, and ether lipid analogues as inhibitors of phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase signaling and cancer cell growth. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:3303–3306. doi: 10.1021/jm980254j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Castillo SS, Brognard J, Petukhov PA, Zhang C, Tsurutani J, Granville CA, Li M, Jung M, West KA, Gills JG, Kozikowski AP, Dennis PA. Preferential inhibition of Akt and killing of Akt-dependent cancer cells by rationally designed phosphatidylinositol ether lipid analogues. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2782–2792. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Brognard J, Clark AS, Ni Y, Dennis PA. Akt/protein kinase B is constitutively active in non-small cell lung cancer cells and promotes cellular survival and resistance to chemotherapy and radiation. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3986–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gills JJ, Castillo SS, Zhang C, Petukhov PA, Memmott RM, Hollingshead M, Warfel N, Han J, Kozikowski AP, Dennis PA. Phosphatidylinositol ether lipid analogues that inhibit AKT also independently activate the stress kinase, p38α, through MKK3/6-independent and -dependent mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:27020–27029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ho A, Dowdy SF. Regulation of G(1) cell-cycle progression by oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2002;12:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(01)00263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cheng M, Sexl V, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. Assembly of cyclin D-dependent kinase and titration of p27Kip1 regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK1) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:1091–1096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhang Q, Sakamoto K, Liu C, Triplett AA, Lin WC, Rui H, Wagner KU. Cyclin D3 compensates for the loss of cyclin D1 during ErbB2-induced mammary tumor initiation and progression. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7513–7524. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Geng Y, Whoriskey W, Park MY, Bronson RT, Medema RH, Li T, Weinberg RA, Sicinski P. Rescue of cyclin D1 deficiency by knockin cyclin E. Cell. 1999;6:767–777. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80788-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]