Abstract

Background

Current biochemical indicators cannot discriminate between parenchymal, biliary, vascular, and neoplastic hepatobiliary diseases. MicroRNAs are promising new biomarkers for hepatobiliary disease in humans and dogs.

Objective

To measure serum concentrations of an established group of microRNAs in dogs and to investigate their concentrations in various types of hepatobiliary diseases.

Animals

Forty‐six client‐owned dogs with an established diagnosis of hepatobiliary disease and stored serum samples and eleven client‐owned healthy control Labrador Retrievers.

Methods

Retrospective study. Medical records of dogs with parenchymal, biliary, vascular, or neoplastic hepatobiliary diseases and control dogs were reviewed. Concentrations of miR‐21, miR‐122, miR‐126, miR‐148a, miR‐200c, and miR‐222 were quantified in serum by real‐time polymerase chain reaction.

Results

No different microRNA concentrations were found in the adenoma and congenital portosystemic shunt groups. In all other diseases, miR‐122 concentrations were elevated with the highest concentration in the mucocele group (267‐fold, CI: 40–1,768, P < .001). In dogs with biliary diseases, miR‐21 and miR‐222 were only increased in dogs with mucoceles (26‐fold, CI: 5–141, P = .005 and 13‐fold, CI: 2–70, P = .025, respectively). Uniquely increased microRNAs were found in the hepatocellular carcinoma group (miR‐200c, 35‐fold increase, CI: 3–382, P = .035) and the chronic hepatitis group (miR‐126, 22‐fold increase, CI: 5–91, P = .002).

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

A microRNA panel consisting of miR‐21, miR‐122, miR‐126, miR‐200c, and miR‐222 can distinguish between parenchymal, biliary, and neoplastic hepatobiliary diseases. Serum microRNA profiling is a promising new tool that might be a valuable addition to conventional diagnostics to help diagnose various hepatobiliary diseases in dogs.

Keywords: Biomarker, Hepatitis, Mucocele, Neoplasia

Abbreviations

- AH

acute hepatitis

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AP

alkaline phosphatase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- BA

bile acids

- BI

other biliary diseases; cholangitis or extrahepatic bile duct obstruction

- CDmiR

cholangiocyte‐derived microRNA

- CH

chronic hepatitis

- CI

confidence interval

- CPSS

congenital portosystemic shunts

- GGT

gamma‐glutamyltransferase

- HCA

hepatocellular adenoma

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HDmiR

hepatocyte‐derived microRNA

- L

lymphoma

- MU

mucocele

- NL

normal liver

- RT‐PCR

real‐time polymerase chain reaction

Hepatobiliary diseases are commonly encountered in dogs and can be divided into 4 main groups: parenchymal, biliary, vascular, or neoplastic diseases.1 In many cases, clinical signs of hepatobiliary diseases are nonspecific. To establish a tative diagnosis, biochemical blood parameters are used as a first step in most cases. Several laboratory tests can be used to evaluate hepatocellular damage and hepatic function. The most commonly used biochemical indicators of hepatobiliary injury are alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (AP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and gamma‐glutamyltransferase (GGT).2 To confirm the existence of significant hepatic impairment, liver function tests can be performed, including measurements of bilirubin, bile acids (BA), and ammonia levels in blood.3, 4 With the exception of some vascular hepatic diseases (i.e, congenital portosystemic shunts),5 biochemical indicators function at best establishing the presence of hepatobiliary disease but are usually not sufficient to specify the underlying disease.

A thorough and extensive diagnostic workup including imaging techniques, cytology and culture of bile, and cytologic and histopathologic evaluation of liver biopsies is usually necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis.1 A relatively noninvasive sensitive and specific blood‐based biomarker profile that can differentiate between various types of hepatobiliary disease can potentially restrict or specify follow‐up tests and be a valuable addition in current diagnostic workup protocols.

Mature microRNAs are a class of small noncoding RNAs that are important regulators of posttranscriptional gene expression.6 With critical functions in the regulation of multiple aspects of hepatic development, microRNAs have recently emerged as promising and stable candidate biomarkers for a variety of hepatobiliary diseases in humans.7, 8, 9 Several hepatocyte‐derived microRNAs (HDmiRs) and cholangiocyte‐derived microRNAs (CDmiRs) have been shown to be sensitive and stable candidate biomarkers in human patients with acute or chronic liver injury caused by various etiologies, for example drug‐ or hepatitis C virus‐induced liver injury.10, 11, 12 Studies focusing on neoplastic diseases demonstrated different serum concentrations of several microRNAs in human patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or hepatocellular carcinoma versus normal patients.13, 14, 15 The first aim of this exploratory study was to evaluate whether the concentrations of a selected group of hepatocyte‐derived, cholangiocyte‐derived, and oncogenic microRNAs, based on the current human literature, were measurable in serum of dogs with parenchymal, biliary, vascular, or neoplastic hepatobiliary diseases. Our second aim was to explore the possibility of using a serum microRNA profile as a biomarker for canine hepatobiliary diseases by providing an overview of serum concentrations of select microRNAs in dogs with parenchymal, biliary, vascular, or neoplastic hepatobiliary diseases.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Medical records of dogs referred to the Department of Clinical Sciences of Companion Animals, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, between 1999 and 2014 were reviewed. Data concerning signalment, physical examination, biochemical, ultrasonographic, cytologic, and histopathologic findings were retrieved from the medical records. At time of admission, all dogs underwent physical examination, a biochemistry panel (including at least ALT, AP, and BA), and ultrasonographic examination of the hepatobiliary system. Of the 4 main groups of hepatic diseases, that is, parenchymal, biliary, vascular, or neoplastic, 8 subgroups were distinguished in this study. Parenchymal diseases included dogs with acute hepatitis (AH) or chronic hepatitis (CH). Biliary diseases were divided into mucoceles (MU) and dogs with cholangitis (lymphocytic or destructive) or extrahepatic bile duct obstruction, the latter two termed “other biliary diseases” (BI). The vascular disease group solely contained dogs with congenital portosystemic shunts (CPSS). The neoplastic diseases group included dogs with hepatocellular adenomas (HCA), hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC), and hepatic lymphoma (L). The final diagnosis of AH, CH, BI, HCA, and HCC was established by the evaluation of a histologic liver biopsy. The presence of L was established by histology or cytology. Diagnostic criteria for MU included the typical appearance of an enlarged gallbladder with immobile, echogenic bile with a striated or stellate pattern during ultrasonographic examination,16 histologically confirmed after surgical removal of the gall bladder, or both modalities. The presence of CPSS was confirmed either on surgery or a CT‐contrast study. All subgroups contained at least 5 confirmed cases. Control dogs (normal liver group, NL) were Labrador Retrievers, selected from the database from an ongoing research program about copper‐associated hepatitis of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University.17 All control dogs were clinically healthy Labrador Retrievers that underwent a liver biopsy for screening for copper‐associated hepatitis. The control dogs had a normal biochemistry panel, unremarkable abdominal ultrasound, and absence of hepatic disease on histopathologic evaluation of a liver biopsy. Of all dogs included in the study, clinical data as well as biological material (i.e, serum samples) were stored until further analysis was performed. Abdominal ultrasounds were performed by board‐certified radiologists. Histology was evaluated by a board‐certified veterinary pathologist (GCMG) according to the World Small Animal Veterinary Association standards and who was unaware of the results of the microRNA analysis at the time of histopathologic evaluation.1 All data were collected according to the Act on Veterinary Practice, as required under Dutch legislation, and all procedures were known and approved by the Animal Welfare Body of the University of Utrecht.

RNA Isolation

Serum samples obtained at the time of diagnostic workup of the dogs were stored at −20°C or −70°C until microRNA analysis. Total RNA was extracted from 100 μL serum with a miRNeasy Serum/Plasma kit,1 following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, RNA was extracted from the serum by lysis reagent (500 μL) and chloroform (100 μL). After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C, the aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh tube with 450 μL of ethanol. RNA was purified on a RNeasy minElute spin column1 and eluted in 14 μL RNase‐free water and stored at −20°C. Normalization was achieved by adding 5.6 × 108 copies of synthetic C. elegans miR‐39 spike‐in control1 after the addition of lysis reagent, before the addition of chloroform and the phase separation.

Reverse Transcription and Real‐Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT‐PCR)

The miScript II Reverse Transcription kit1 was used to prepare cDNA according to the manufacturer's instructions. The obtained cDNA was diluted to a total volume of 200 μL. Based on the current human literature, the serum concentrations of miR‐122 and miR148a (HDmiRs in humans), miR‐21 and miR‐126 (oncogenic miRs in human), and miR‐200c and miR‐222 (CDmiRs in humans) were chosen to be measured in dogs with various hepatic diseases.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 RT‐PCR was performed with the miScript SYBR Green PCR kit.1 All PCRs were carried out in duplicate in a CFX‐384 Real‐Time PCR detection system.2 Each reaction consisted of 5 μL 2× QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, 1 μL 10× universal primer, 1 μL 10× miR‐specific primer1, and 1 μL of the previously diluted cDNA. The total reaction volume of each PCR was adjusted to 10 μL by adding 2 μL RNase‐free water. The concentrations of all microRNAs were quantified by absolute quantification via a standard curve, with quantities normalized to the spike‐in control.24

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized as median and range for summary statistics of the study subjects. Linear regression was used with miRNA serum concentrations as dependent variables and diagnostic group as independent variable. Eight diseased groups (AH, CH, BI, MU, CPSS, HCA, HCC, and L) were included, and the normal liver group was used as the reference category. The natural logarithm of the different microRNAs was taken to ensure validity of all models, which was checked by studying the residuals on normality and constant variance. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons by the Benjamini–Hochberg correction. Data were analyzed by R statistics (version 3.1.2).3

Results

Dog Characteristics

Serum samples of 57 dogs were analyzed (11 healthy, 46 with hepatic disease). Dog characteristics including sex, age, bile acids, and liver transaminases are summarized in Table 1. Dogs from the hepatobiliary disease groups consisted of crossbreeds (n = 9), Labrador Retrievers (n = 6), English cocker spaniels (n = 6), Golden Retrievers (n = 4), Cairn terriers (n = 3), Maltese dogs (n = 2), miniature pinschers (n = 2), Scottish terriers (n = 2), and one of each of the following breeds: Beagle, Bernese mountain dog, Bouvier des Flandres, Cavalier King Charles spaniel, Dobermann, German Shepherd, Fox terrier, Munsterlander, Polish lowland sheepdog, Shetland Sheepdog, Shih Tzu, and Tibetan terrier.

Table 1.

Dog characteristics

| Age (years), median and range | Sex (F, M) | ALT (U/L), median and range (ref <70 U/L) | AP (U/L), median and range (ref <89 U/L) | BA (μmol/L), median and range (ref <10 μmol/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL (n = 11) | 5.4 (3.6–7.3) | 8F, 3M | 38 (23–64) | 34 (14–94) | 1 (0–6) |

| AH (n = 6) | 7.3 (5.5–14.5) | 5F, 1M | 233 (54–845) | 178 (29–1,920) | 9 (1–153) |

| CH (n = 6) | 6.4 (3.3–11.7) | 5F, 1M | 268 (29–2,258) | 494 (23–1,200) | 15 (2–112) |

| MU (n = 5) | 8.2 (2.6–13.0) | 4F, 1M | 2,000 (823–4,590) | 3,094 (1,019–8,305) | 528 (62–660) |

| BI (n = 6) | 9.2 (5.8–13.2) | 4F, 2M | 933 (408–2,700) | 2,995 (208–3,850) | 432 (20–1,605) |

| CPSS (n = 5) | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 2F, 3M | 83 (22–225) | 112 (103–183) | 79 (19–221) |

| HCA (n = 6) | 11.8 (6.7–15.2) | 3F, 3M | 837 (85–1,556) | 1,548 (354–7,390) | 24 (6–118) |

| HCC (n = 6) | 9.2 (4.8–11.1) | 3F, 3M | 467 (42–1,300) | 943 (29–4,175) | 55 (5–415) |

| L (n = 6) | 8.5 (5.4–9.9) | 2F, 4M | 338 (179–894) | 1,375 (325–4,625) | 67 (11–555) |

AH, acute hepatitis; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AP, alkaline phosphatase; BA, bile acids; BI, other biliary diseases (cholangitis or extrahepatic bile duct obstruction); CH, chronic hepatitis; CPSS, congenital portosystemic shunts; F, female; HCA, hepatocellular adenoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; L, lymphoma; M, male; MU, mucoceles; NL, normal liver; ref, reference; SD, standard deviation.

MicroRNA Serum Concentrations in Dogs with Hepatic Disease

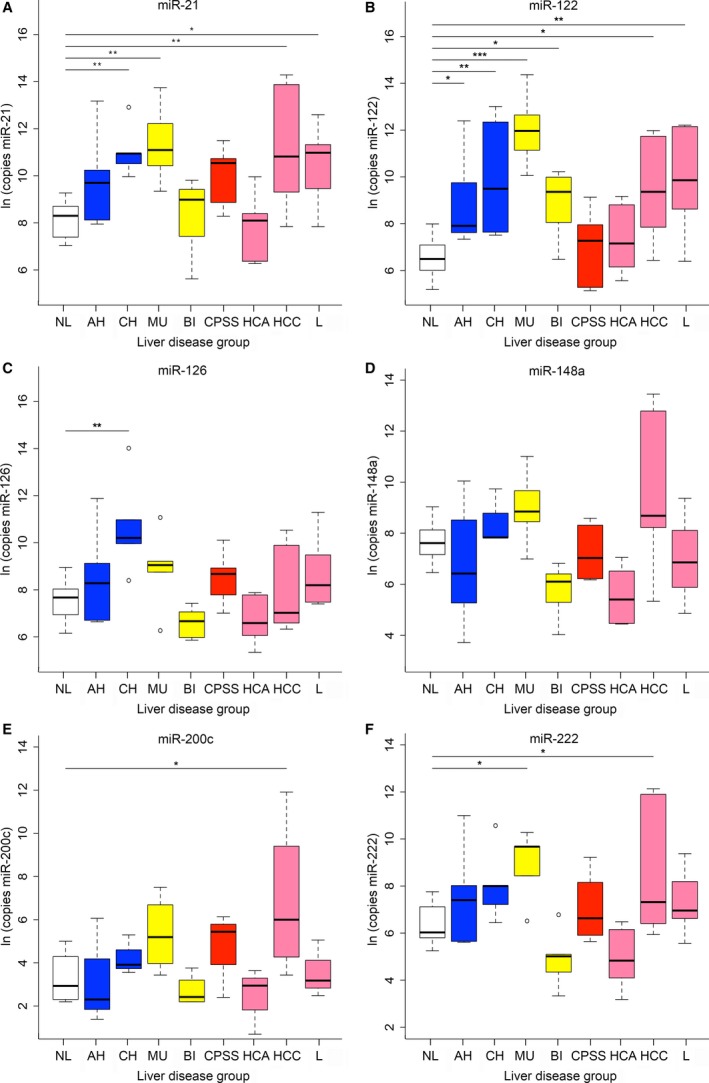

Full list of fold changes, confidence intervals, and P values of microRNA concentrations in dogs with various hepatobiliary diseases relative to microRNA concentrations in the normal liver group are summarized in supplementary Table 1. Except for miR‐148a, all microRNAs were higher in one or more disease groups (Figs 1, 2) compared to the normal group. In dogs with HCA and CPSS, none of the tested microRNAs were higher compared to the normal liver group. MicroRNA‐122 concentrations were increased in all parenchymal diseases (AH, CH), biliary diseases (MU, BI), and 2 neoplastic diseases (HCC, L) compared to controls. miR‐122 was the highest microRNA in the MU group, with a 267‐fold upregulation (CI: 40–1,768, P < .001) compared to control.

Figure 1.

MicroRNA concentrations in dogs with normal livers (white) and in dogs with parenchymal (blue), biliary (yellow), vascular (red), or neoplastic (pink) hepatobiliary disease. (A) miR‐21, (B) miR‐122, (C) miR‐126, (D) miR‐148a, (E) miR‐200c, (F) miR‐222. Significant differences between groups of hepatobiliary diseases and the normal liver group are marked with stars (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001). AH, acute hepatitis (n = 6); BI, other biliary diseases (cholangitis or extrahepatic bile duct obstruction, n = 6); CH, chronic hepatitis (n = 6); CPSS, congenital portosystemic shunts (n = 5); HCA, hepatocellular adenoma (n = 6); HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 6); L, lymphoma (n = 6); Ln, natural logarithm; MU, mucoceles (n = 5); NL, normal liver (n = 11).

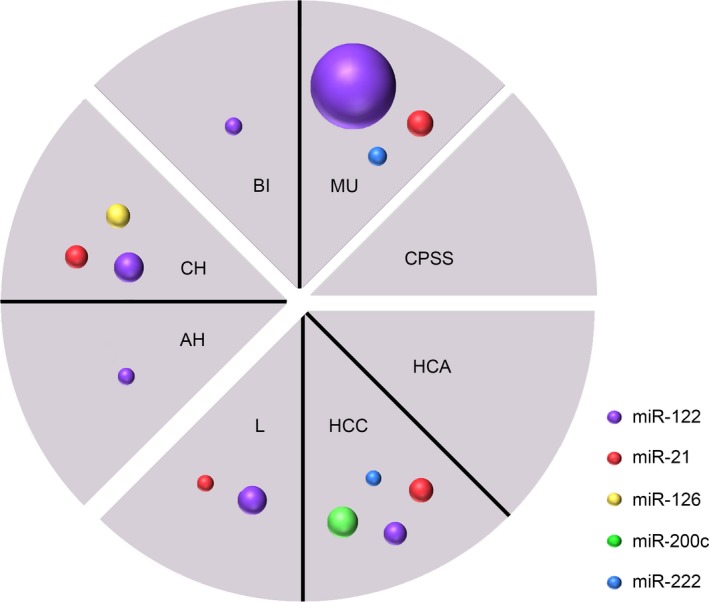

Figure 2.

Disease‐based microRNA profile. Colored circles indicate relative increase in microRNA concentrations compared to the normal liver group (n = 11). Pie charts indicate main groups of hepatic disease (parenchymal, biliary, vascular, or neoplastic diseases). Dogs with mucoceles (MU, n = 5), hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC, n = 6), lymphomas (L, n = 6), and chronic hepatitis (CH, n = 6) all have their own unique microRNA profile. No microRNA increase is seen in dogs with adenomas (HCA, n = 6) and congenital portosystemic shunts (CPSS, n = 5). AH, acute hepatitis (n = 6); BI, other biliary diseases (cholangitis or extrahepatic bile duct obstruction, n = 6).

The second most often increased microRNA was miR‐21. Compared to dogs with normal livers, miR‐21 concentrations were increased in the MU, CH, HCC, and L groups. In dogs with biliary diseases, miR‐21 and miR‐222 were only increased in dogs with mucoceles (26‐fold, CI: 5–141, P = .005 and 13‐fold, CI: 2–70, P = .025, respectively), as dogs with cholangitis or extrahepatic bile duct obstruction did not have increased miR‐21 or miR‐222 concentrations. In dogs with parenchymal diseases, miR‐21 was only increased in dogs with CH (19‐fold, CI: 5–141, P = .005) and not in dogs with AH. MicroRNA‐222 was increased in dogs with MU and HCC compared to normal dogs (13‐fold, CI: 2–70, P = .025 and 9‐fold, CI: 2–42, P = .041, respectively). Both miR‐200c and miR‐126 were uniquely increased in one disease group. From all microRNAs increased in the HCC group, miR‐200c had the highest concentrations, with a 35‐fold increase (CI: 3–383, P = .035), compared to the normal liver group. With a 22‐fold increase (CI: 5–91, P = .002), miR‐126 was only significantly expressed in the CH group.

Discussion

Results of this study demonstrate that a panel of different microRNAs in dogs with hepatobiliary disease could be possibly used in the future as a diagnostic marker for different hepatobiliary diseases in dogs. Current biochemical blood parameters of hepatobiliary injury and dysfunction cannot discriminate between most hepatobiliary diseases.4, 25 The gold standard to differentiate between these diseases is histopathologic evaluation of liver biopsy specimens after ultrasonographic examination of the liver and biliary tract system.1 It would be of great value to use a relative noninvasive biomarker to characterize the type of hepatobiliary disease. MicroRNAs are emerging as biomarkers for hepatic disease because they play critical roles in liver development and metabolism and are measurable in blood even after prolonged storage.7, 21, 26 MicroRNAs are already evaluated as promising biomarkers for hepatobiliary disease, including primary hepatic tumors, in humans.8, 9 In dogs, serum HDmiR‐122 and HDmiR‐148a have shown to be increased upon hepatocellular injury.27, 28 In the present study, we demonstrated different concentrations of our selected microRNA panel in dogs with several parenchymal, biliary, and neoplastic diseases. This is the first evidence that a microRNA panel might be a valuable extra diagnostic tool, helping in diagnosing and differentiating several common hepatobiliary diseases in dogs.

One of the diseases evaluated in this study was congenital portosystemic shunts. None of the microRNA showed significantly increased concentrations in this group. Several studies in man and dogs demonstrated an increase in serum miR‐122 upon hepatocellular injury.18, 21, 27, 28 One can presume that in the case of congenital portosystemic shunting, there is not enough hepatocellular injury to give a rise in microRNA concentrations. Of all common hepatic diseases, this is the only disease of which a presumptive diagnosis can be made based on signalment (age, breed), clinical signs and an ammonia tolerance test, fasting plasma ammonia, fasting plasma bile acids, or bile acid stimulation test.5, 29 Therefore, microRNA profiling seems to be of no added value in this group of diseases.

In dogs with hepatobiliary disease, the liver parenchyma, gallbladder, and biliary tree can be further evaluated with ultrasonography. However, in 20% of dogs with a primary hepatitis, no abnormalities are found on abdominal ultrasound.30 Our previous study reported miR‐122 to have a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 82% in detecting dogs with hepatocellular injury.28 Results of this study indeed demonstrate an increase in miR‐122 in both dogs with acute and chronic hepatitis. Although recent studies in humans21 and dogs28 also showed an increase in miR‐148a after hepatocellular injury, no significant difference in serum concentrations was seen in the present study after correction for multiple testing.

In dogs with neoplastic disease, ultrasonographic examination of the liver can identify nodules or mass lesions. However, it is often not possible to distinguish between hepatocellular adenoma and carcinoma or between neoplasms and nodular hyperplasia or cirrhosis.31 In case of hepatic lymphoma, the liver can appear ultrasonographically unremarkable or hypoechoic and diffusely enlarged.31, 32 This emphasizes the importance of a noninvasive microRNA panel that is able to differentiate between causes of hepatic lesions. Several studies in human patients state that single serum measurements of miR‐21, miR‐122, and miR‐222 could not differ between hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis,33, 34, 35 and only one study reported that miR‐21 was higher in human patients with hepatocellular carcinoma compared to patients with hepatitis.13 However, in our study, we showed that specific microRNA concentrations were increased in dogs with hepatitis and hepatocellular lymfomas and carcinomas. This suggests that a panel of miR‐21, miR‐122, miR‐126, miR‐200c, and miR‐222 are possible candidates for a biomarker panel in the discrimination of AH, CH, HCA, HCC, and L in dogs.

One of the most important findings of this study was the increased serum concentration of miR‐200c, miR‐21, miR‐222, and miR‐122 in dogs with HCC. All of these microRNAs are associated with several (human) cancer types, especially miR‐21 and miR‐200c. The miR‐200 family is known to be a powerful regulator in epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition as occurs in embryogenesis, carcinogenesis, and remodeling responses of adult (liver) tissue after damage.36, 37, 38 In our study, miR‐200c was only found to be increased in the HCC group compared to controls. MicroRNA‐21 is suggested to contribute to a malignant phenotype by exerting both antiapoptotic39 and tumor disseminating properties.19, 40Although tissue miR‐126 is thought to play critical roles in several human cancers as well,23 we did not see any difference in serum miR‐126 between dogs with liver cancer and control dogs. This might be because of a difference between tissue expression and serum presence of miR‐126, as serum microRNA release does not necessarily correlate to tissue microRNA expression.41 Several studies examined serum concentrations of miR‐21, miR‐122, and miR‐222 in human patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, with similar results as our study in dogs with HCC. Four studies identified an increase in serum miR‐21 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma,13, 33, 35, 42 which is also consistent with our results, as dogs with HCC and L had an increase in miR‐21. In addition, human patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were found to have an increase in serum miR‐12233, 34 and miR‐22234, 42 as well. Interestingly, in our study, none of these microRNAs were increased in dogs with HCA, and only miR‐21 and miR‐122 were increased in dogs with L. The upregulation of miR‐21, miR‐122, miR‐222, and miR‐200c in dogs with L or HCC compared to controls suggests that these microRNAs can be used as a potential biomarker for neoplastic liver disease in dogs.

Dogs with biliary diseases usually have a marked increase in liver enzymes, especially AP, GGT, and high BA (Table 1).4 A future microRNA panel could help in further differentiating underlying disease, making oriented ultrasonographic examination of the hepatobiliary tree possible. In our study, all dogs with biliary tract diseases had high serum miR‐122. This can be explained by hepatocellular damage as a result of cholestasis, and the subsequent release of miR‐122 into serum. Furthermore, we selected miR‐200c and miR‐222 as CDmiRs and therefore expected them to be increased in dogs with biliary diseases. Only one of them, miR‐222, was increased in serum of dogs with MU. An interesting theory that could explain this difference might be the polarized release of CDmiRs and HDmiRs by cholangiocytes and hepatocytes. This was recently investigated in bile and serum samples of human patients.18 Upon impaired liver function and liver injury, cholangiocytes release their CDmiRs into bile rather than blood, resulting in decreased serum concentrations. Concurrently, serum HDmiR‐148a and HDmiR‐122 concentrations were observed to increase upon liver cell injury and their secretion into bile decreased. That there are such striking differences between the MU and BI groups is intriguing. A gallbladder mucocele is an inappropriate accumulation of bile‐laden mucus material occupying the gallbladder lumen. One explanation of higher microRNA concentrations in dogs with mucoceles can be the higher amount of necrosis of the gallbladder wall and intrahepatic bile duct epithelium and thus increased release of microRNAs into serum in dogs with mucoceles.16, 43 Another assumption of the increased miR‐21, miR‐122, and miR‐222 serum concentrations is based on one of the most important histologic features of gallbladder mucoceles: hyperplasia of the mucus‐secreting glands.16, 44, 45 All 3 microRNAs are known to influence cellular proliferation, cell growth, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis, which are common features of hyperplasia.19, 46, 47 Different concentrations of miR‐21, miR‐122, and miR‐222 in the two biliary disease groups compared to the control group again indicate that further investigations into these microRNAs in dogs hold potential for future biomarker development.

The results of this study are a promising new step in the development of a biomarker profile for the evaluation of hepatobiliary disease in dogs. Despite the unarguable potential of circulating microRNAs to act as biomarker, several points need to be addressed. To date, even in the human literature, there is no consensus about the quantification and normalization (reference microRNAs or spike‐in controls) of circulating microRNA concentrations.48 In the veterinary field, microRNA expression studies are scarce, and further studies into detection and quantification of microRNAs have to be conducted. In the present study, all control dogs were Labrador Retrievers. As the research of microRNAs in dogs is limited, there is nothing known about breed‐, sex‐, or age‐related differences of microRNA expression in dogs. Because of the highly conserved nature of microRNAs between species with similar physiology,49 we do not expect microRNA concentrations to differ between breeds. In humans, microRNA concentrations have proven to be stable under low‐temperature storage conditions50, 51 and over a long period of time,52 resistant and reproducible and for most microRNAs, there is no difference in expression between female or male individuals.53 Although age‐related differences in humans are described, these are mainly found comparing healthy adults with healthy octogenarians, nonagenarians, or centenarians.54, 55 Dogs in the present study are, with exception of dogs with congenital portosystemic shunting, of comparable age, and age‐related effects in microRNA concentrations are therefore considered negligible. In addition, group size in the present study was small, and to determine test performance of this microRNA profile, this study should be extended with larger cohorts, and possibly more microRNA markers. Furthermore, only HDmiR‐122 has shown to be liver specific as it accounts for 72% of all liver microRNAs with almost no extrahepatic expression.22, 56 Because all other microRNAs lack specificity for the hepatobiliary tree, dogs suffering from extrahepatic diseases, including metastatic liver disease and dogs with nonspecific reactive hepatitis, should be included in subsequent studies to indicate specificity of this microRNA panel. In the present study, corresponding tissue microRNA expression was not measured. At the moment, the relationship between tissue and serum microRNAs remains unclear, justifying the need for further investigations into tissue microRNA expression and release. Based on the study of Verhoeven et al.,18 which indicates notable amounts of microRNAs in bile, more research into the combination of serum and biliary microRNAs as biomarker for hepatic disease is warranted.

In conclusion, we propose that a serum microRNA panel might be used as a diagnostic marker for hepatobiliary diseases in dogs and therefore can be a promising and valuable addition to the currently available diagnostic tools. Therefore, further studies are needed to confirm these findings and to determine corresponding sensitivity and specificity. In addition, further studies into the release of microRNAs in serum and bile and the correlation with expression in liver tissue are warranted to shed light on the role of microRNAs in hepatic disease and their usefulness as relative noninvasive biomarkers in dogs.

Supporting information

Table S2. Increase in microRNA concentrations in dogs with different hepatobiliary diseases compared to control dogs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hans Vernooij for providing statistical advice.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Off‐label Antimicrobial Declaration: Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

Fieten and Spee contributed equally to the work.

This study was performed at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands. It was partially financially supported by the European College of Veterinary Internal Medicine—Companion Animals (ECVIM‐CA) clinical studies fund 2014.

Footnotes

Qiagen, Valencia, CA

Bio‐Rad, Veenendaal, The Netherlands

R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria 2014

References

- 1. The WSAVA Liver Standardization Group . WSAVA Standards for Clinical and Histological Diagnosis of Canine and Feline Liver Diseases, 1st ed Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:144. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Center SA. Interpretation of liver enzymes. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2007;37:297–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schlesinger DP, Rubin SI. Serum bile acids and the assessment of hepatic function in dogs and cats. Can Vet J 1993;34:215–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Center SA, ManWarren T, Slater MR, Wilentz E. Evaluation of twelve‐hour preprandial and two‐hour postprandial serum bile acids concentrations for diagnosis of hepatobiliary disease in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991;199:217–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Straten G, Spee B, Rothuizen J, et al. Diagnostic value of the rectal ammonia tolerance test, fasting plasma ammonia and fasting plasma bile acids for canine portosystemic shunting. Vet J 2015;204:282–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W. The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat Rev Genet 2010;11:597–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen Y, Verfaillie CM. MicroRNAs: The fine modulators of liver development and function. Liver Int 2014;34:976–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gradilone SA, O'Hara SP, Masyuk TV, et al. MicroRNAs and benign biliary tract diseases. Semin Liver Dis 2015;35:26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farid WR, Verhoeven CJ, Jonge J, et al. The ins and outs of microRNAs as biomarkers in liver disease and transplantation. Transplant Int 2014;27:1222–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van der Meer AJ, Farid WR, Sonneveld MJ, et al. Sensitive detection of hepatocellular injury in chronic hepatitis C patients with circulating hepatocyte‐derived microRNA‐122. J Viral Hepat 2013;20:158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Starkey Lewis PJ, Dear J, Platt V, et al. Circulating microRNAs as potential markers of human drug‐induced liver injury. Hepatology 2011;54:1767–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. John K, Hadem J, Krech T, et al. MicroRNAs play a role in spontaneous recovery from acute liver failure. Hepatology 2014;60:1346–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tomimaru Y, Eguchi H, Nagano H, et al. Circulating microRNA‐21 as a novel biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karakatsanis A, Papaconstantinou I, Gazouli M, et al. Expression of microRNAs, miR‐21, miR‐31, miR‐122, miR‐145, miR‐146a, miR‐200c, miR‐221, miR‐222, and miR‐223 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma or intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and its prognostic significance. Mol Carcinog 2013;52:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Borel F, Konstantinova P, Jansen PL. Diagnostic and therapeutic potential of miRNA signatures in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:1371–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Besso JG. Ultrasonographic appearance and clinical findings in 14 dogs with gallbladder mucocele. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2000;41:261–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fieten H, Hooijer‐Nouwens B, Biourge V, et al. Association of dietary copper and zinc levels with hepatic copper and zinc concentration in Labrador retrievers. J Vet Intern Med 2012;26:1274–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Verhoeven CJ, Farid WR, Roest HP, et al. Polarized release of repatic microRNAs into bile and serum in response to cellular injury and impaired liver function. Liver Int 2016;36:883–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meng F. MicroRNA‐21 Regulates expression of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in human hepatocellular cancer. Gastroenterology 2007;133:647–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen L. The role of microRNA expression pattern in human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol 2009;50:358–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Farid WR, Pan Q, van der Meer AJ, et al. Hepatocyte‐derived microRNAs as serum biomarkers of hepatic injury and rejection after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2012;18:290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, et al. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell 2007;129:1401–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ebrahimi F. miR‐126 in Human Cancers: Clinical roles and current perspectives. Exp Mol Pathol 2014;96:98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kroh EM, Parkin RK, Mitchell PS, Tewari M. Analysis of circulating microRNA biomarkers in plasma and serum using quantitative Reverse Transcription‐PCR (qRT‐PCR). Methods 2010;50:298–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neumann S. Comparison of blood parameters in degenerative liver disease and liver neoplasia in dogs. Comp Clin Path 2004;12:206–210. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grasedieck S, Schöler N, Bommer M, et al. Impact of serum storage conditions on microRNA stability. Leukemia 2012;26:2414–2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harrill AH, Eaddy JS, Rose K, et al. Liver biomarker and in vitro assessment confirm the hepatic origin of aminotransferase elevations lacking histopathological correlate in beagle dogs treated with GABAA receptor antagonist NP260. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2014;277:131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dirksen K, Verzijl T, van den Ingh TS, et al. Hepatocyte‐derived microRNAs as sensitive serum biomarkers of hepatocellular injury in Labrador retrievers. Vet J 2016;211:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kerr MG, van Doorn T. Mass screening of Irish Wolfhound puppies for portosystemic shunts by the dynamic bile acid test. Vet Rec 1999;144:693–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Poldervaart JH, Favier RP, Penning LC, et al. Primary hepatitis in dogs: A retrospective review (2002–2006). J Vet Intern Med 2009;23:72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kemp S, Panciera D, Larson M, et al. A comparison of hepatic sonographic features and histopathologic diagnosis in canine liver disease: 138 cases. J Vet Intern Med 2013;27:806–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Warren‐Smith C, Andrew S, Mantis P, Lamb C. Lack of associations between ultrasonographic appearance of parenchymal lesions of the canine liver and histological diagnosis. J Small Anim Pract 2012;53:168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xu J, Wu C, Che X, et al. Circulating microRNAs, miR‐21, miR‐122, and miR‐223, in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma or chronic hepatitis. Mol Carcinog 2011;50:136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qi P. Serum microRNAs as biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma in chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e28486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bihrer V. Serum microRNA‐21 as marker for necroinflammation in hepatitis C patients with and without hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e26971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Choi SS. Epithelial‐to‐Mesenchymal transitions in the liver. Hepatology 2009;50:2007–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Park S, Gaur A, Lengyel E, Peter M. The miR‐200 family determines the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells by targeting the E‐Cadherin repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Genes Dev 2008;22:894–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gregory PA. The miR‐200 family and miR‐205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat Cell Biol 2008;10:593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chan J, Krichevsky A, Kosik K. MicroRNA‐21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res 2005;65:6029–6033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Asangani IA. MicroRNA‐21 (miR‐21) post‐transcriptionally downregulates tumor suppressor Pdcd4 and stimulates invasion, intravasation and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Oncogene 2008;27:2128–2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brase JC, Wuttig D, Kuner R, Sültmann H. Serum microRNAs as non‐invasive biomarkers for cancer. Mol Cancer 2010;9:306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li J. Expression of serum miR‐221 in human hepatocellular carcinoma and its prognostic significance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011;406:70–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Crews LJ. Clinical, ultrasonographic, and laboratory findings associated with gallbladder disease and rupture in dogs: 45 cases (1997–2007). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2009;234:359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pike FS. Gallbladder mucocele in dogs: 30 cases (2000–2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004;224:1615–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aguirre AL. Gallbladder disease in Shetland Sheepdogs: 38 cases (1995–2005). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2007;231:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu K, Liu S, Zhang W, et al. miR222 regulates sorafenib resistance and enhance tumorigenicity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol 2014;45:1537–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xu J. MicroRNA‐122 suppresses cell proliferation and induces cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by directly targeting Wnt/ß‐Catenin pathway. Liver Int 2012;32:752–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reid G, Kirschner MB, van Zandwijk N. Circulating microRNAs: Association with disease and potential use as biomarkers. Crit Rev Oncol 2011;80:193–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ason B, Darnell DK, Wittbrodt B, et al. Differences in vertebrate microRNA expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:14385–14389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gilad S, Meiri E, Yogev Y, et al. Serum microRNAs are promising novel biomarkers. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mráz M, Malinova K, Mayer J, Pospisilova S. MicroRNA isolation and stability in stored RNA samples. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009;390:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rounge TB, Lauritzen M, Langseth H, et al. microRNA biomarker discovery and high‐throughput DNA sequencing are possible using long‐term archived serum samples. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24:1381–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, et al. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: A novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res 2008;18:997–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. ElSharawy A, Keller A, Flachsbart F, et al. Genome‐wide miRNA signatures of human longevity. Aging Cell 2012;11:607–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Olivieri F, Spazzafumo L, Santini G, et al. Age‐related differences in the expression of circulating microRNAs: mir‐21 as a new circulating marker of inflammaging. Mech Ageing Dev 2012;133:675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lagos‐Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, et al. Identification of tissue‐specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol 2002;12:735–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S2. Increase in microRNA concentrations in dogs with different hepatobiliary diseases compared to control dogs.