Fumonisins are thermostable toxins produced by Fusarium spp. These fungi commonly contaminate corn and other types of cereal1; nevertheless, they rarely contaminate hay, and when contamination occurs, it is uncommonly a toxic strain. These mycotoxins were first described by a study group in South Africa after 20 years of searching for the substance produced by F. moniliforme that causes leukoencephalomalacia.2

There are 2 types of fumonisins among the varieties previously described that can cause neurological conditions, that is, fumonisins B1 and B2, which are produced by 3 species of Fusarium: F. moniliforme, F. proliferatum, and F. subglutinans. The first species is most frequently isolated worldwide.3 The mycoflora of 39 concentrated samples associated with confirmed leukoencephalomalacia cases in Brazil has been reported; F. moniliforme was found in 82%, F. proliferatum in 12.8%, and F. subglutinans in 2.6% of samples.4 In the United States, from the fall of 1989 to the winter of 1990, 45 samples of feed obtained from confirmed leukoencephalomalacia cases contained F. moniliforme, 5 as did samples obtained from cases from Mexico.6

Animals affected by leukoencephalomalacia die suddenly, with or without the occurrence of clinical manifestations. The common manifestations are anorexia, lethargy, hypersensitivity and agitation, sweating, muscle fasciculation and weakness, hypermetria, staggering, circling, inability to swallow, blindness, dilated pupils, absence of a pupillary light reflex, head pressing, and tonic‐clonic seizures.7 This disease should be considered in the differential diagnosis of traumatic brain injury, arboviral encephalitis, hepatic encephalopathy, equine protozoal myeloencephalitis, Theiler's disease, and botulism.8

The histopathological lesions noted in the central nervous system include hemorrhage, malacia, and perivascular congestion involving the white matter of the brain.9 In the liver, lobular necrosis, periportal fibrosis, periportal vacuolation, and a proliferation of bile ducts can be found.5, 10

Leukoencephalomalacia is a well‐known disease in veterinary medicine. The disease is difficult to diagnose, which delay adequate treatment and management, resulting in the death of many animals. Fungal isolation and quantification of fungal mycotoxins on grain are commonly performed when there is a suspicion of leukoencephalomalacia; however, this procedure is rarely carried out on hay. We found no study in the literature describing this disease as a result of eating contaminated hay.

Case Report

On 2 properties located in different cities of the same state in Brazil, a total of 13 horses died. The horses presented with acute sialorrhea, lethargy, ataxia, and sweating, which evolved to death over a period of approximately 24 hour. For diagnostic and treatment purposes, an 8‐year‐old male Quarter Horse was referred to the Veterinary Hospital, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science of the University of São Paulo.

The horse had shown sialorrhea, lethargy, and intermittent bouts of colic and had been treated on one of the properties with gastric lavage, anti‐inflammatory drugs, fluids, and dimethyl sulfoxide. There was no sign of improvement after the initial treatment, and the horse developed ataxia and muscular fasciculation.

The feed consisted of 2 kg of grain twice a day and coast cross hay baled in rolls was suspended, and the animal was kept in a stable at night.

At the hospital, the horse had a heart rate of 130 bpm, respiratory rate of 46 breaths per minute, temperature of 40.4°C, capillary refill time of 3 second, decreased intestinal motility, and pink and moist mucous membranes. The animal was ataxic, hypermetric, and was agitated with intense muscle fasciculation and sweating. The horse became excited when it was handled, fell down, and could not stand despite assistance. Sedation with detomidine (10 μg/kg) and butorphanol (0.02 mg/kg) was required to control agitation. Treatment with fluid therapy, mannitol (0.5 g/kg i.v.), and thiamine (1 mg/kg i.m.) was instituted.

Progressive worsening of the spasticity of the pelvic limbs, as well as paddling movements, loss of deep sensitivity, blindness, inability to swallow, lack of menace reflex, dilated pupils with no light reflex, and convulsions were observed. Approximately 24 hour after the manifestation of these signs on the property, the animal died.

Biochemical tests revealed increased total protein, albumin, and total bilirubin concentrations, and azotemia. The complete blood count revealed an increased hematocrit value and neutrophilic leukocytosis as well as monocytosis.

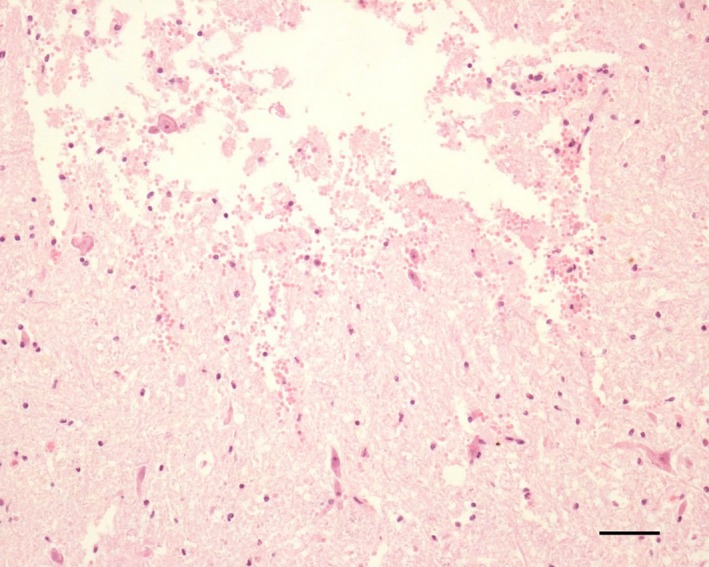

At necropsy, a flattening of the cerebral gyri and softening of the frontal, parietal, and temporal cortices were observed, which were more pronounced in the right hemisphere. Histopathological examination of the brain revealed multiple foci of hemorrhage, edema, and extensive areas of malacia in both the white matter and in adjacent spots of the gray matter, as illustrated in Figure 1. The liver showed acute centrilobular necrosis and discrete diffuse microgoticular vacuolar degeneration of hepatocytes. The histopathological findings in the central nervous system and liver were congruent with leukoencephalomalacia.

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of the white matter of the brain demonstrating hemorrhage and necrosis; hematoxylin and eosin staining; barr: 50 μm.

Given the necropsy and histopathology results, leukoencephalomalacia was the main suspicion. Samples of the grain and hay fed to the horses on the two properties were therefore obtained, and mycological culture and analyses of fumonisin concentrations were performed at the Mycological Laboratory of the Biomedical Science Institute of the University of São Paulo. Consequently, F. moniliforme was identified in the hay from both properties. The fumonisin concentration analyses indicated 0.12 and 0.02 μg/g of fumonisin B1 in the hay from the respective properties. However, no fungal growth or presence of fumonisin was noted in the grain.

The other horses at the property were also treated after the suspicion of neurological manifestations caused by fumonisin poisoning. Removal of the contaminated food, fluid therapy to accelerate the excretion of toxins, administration of mannitol or dimethyl sulfoxide in an attempt to reduce cerebral edema, activated charcoal to neutralize the toxin, and mineral oil to decrease absorption did not prevent the progression of clinical signs, and all affected horses died within 24 to 48 hour of onset of signs.

Discussion

Leukoencephalomalacia can progress to death rapidly in affected animals, within hours to 3 days.11 In this outbreak, all symptomatic animals died within 24 hour. The clinical manifestations and disease course presented by the horses were similar to those reported in the literature,9 differing only in terms of the presence of sialorrhea. Although there is no known classic hematological picture, the findings from the hematological tests were similar to those of reported cases.12 In the necropsy, marked malacia and cavitation of the white manner were not observed, and there was only flattening of the cerebral gyri and softening of the frontal, parietal, and temporal cortices.11, 13 The histopathological findings in this case confirmed a hyperacute case without the classic presence of inflammatory cells, eosinophils, gitter cells, and neutrophils, but with signs of hemorrhage, edema, and necrosis of the white manner.11, 13

The most common sources of fumonisin are corn, cereals, and moldy grain14; the Fusarium fungi are rarely isolated from hay, and when it occurs, it is very uncommonly a toxic strain.15 This outbreak contradicts the literature, because not only growth of F. moniliforme but also the presence of toxic fumonisin was observed from the hay sample. Another report in the literature describes the toxin in a deer pasture, which caused hepatic changes,16 but no isolation of the fungus was made.

The literature considers that food poses a risk to the animal only when the fumonisin concentration exceeds 10 μg/g,5 but this was not the case in our hay analysis. The fumonisin concentrations found in this outbreak were 0.02 and 0.12 μg/g. Other case reports found mycotoxin concentrations in corn and grain samples ranging from 1–126 μg/g8 with 1.3–27 μg/g of fumonisin B1 and 0.1–12.6 μg/g of fumonisin B2,17 confirming that the concentration varies widely.

The fungus contaminates the hay inhomogeneously, and the portion ingested could contain a higher concentration of the toxin. The dosage of fumonisin found in the food does not correspond directly to the total dosage ingested by the animal. Individual susceptibility should also be considered: it has been reported that there is marked variation in the amount of fumonisin (0.31–51.5 g) that had to be consumed to cause the development of disease and death.5

The fact that the hay had been baled probably contributed to the fungal proliferation. The large rolls are usually kept in places unprotected from weather conditions after the hay is baled or after the bale is opened, providing a humid and warm environment for fungal growth inside the roll. This type of hay should be consumed rapidly, kept in a protected location, and carefully inspected before being offered to animals.

The outbreak reported here occurred in an atypical winter in the Southern Hemisphere. The rainy and cold weather of this winter benefited the production of toxin by the fungus, because the production of toxins is enhanced at temperatures around 20°C with humidity.18

Unfortunately, the prognosis for leukoencephalomalacia is poor. The diagnosis of the disease and identification of the source of toxins are important, because the contaminated food can be removed, thus avoiding further consumption and the progression of the disease in other animals. Recognition of the source is also important for management modifications, especially in terms of the use of hay baled in rolls on the properties that had affected animals.

Leukoencephalomalacia caused by the presence of F. moniliforme and its toxin in baled hay has not previously been reported in the literature. In leukoencephalomalacia outbreaks, it is common practice to suspend grain feed, but not hay feeding. Thus, this case report emphasizes the importance of the proper management of hay, and especially hay baled in rolls, to avoid the development of mold and prevent leukoencephalomalacia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Fapesp for the financial support to the publication.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Off‐label Antimicrobial Declaration: Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobial.

References

- 1. Sydenham EW, Shepard GS, Theil PG, et al. Fumonisin contamination of commercial corn‐based human foodstuff. J Agric Food Chem 1991;39:2014–2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bezuidenhout SC, Gelderblom WCA, Gorst‐Allman CP, et al. Structure elucidation of the fumonisins, mycotoxins from Fusarium moniliforme. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun 1988;11:743–745. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Riet‐Correa F, Rivero R, Odriozola E, et al. Mycotoxicoses of ruminants and horses. J Vet Diagn Invest 2013;25:692–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meireles MCA, Corrêa B, Fischman O, et al. Mycoflora of the toxic feeds associated with equine leukoencephalomalacia (ELEM) outbreaks in Brazil. Mycopathologia 1994;127:183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ross PF, Rice LG, Reagor JC, et al. Fumonisin B1 concentrations in feed from 45 confirmed equine leukoencephalomalacia cases. J Vet Diagn Invest 1991;3:238–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosiles MR, Bautista J, Fuentes VO, Ross F. An outbreak of equine leukoencephalomalacia at Oaxaca, Mexico, associated with Fumonisin B1. J Vet Med Assoc 1998;45:299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schmelz EM, Dombrink‐Kurtzman MA, Roberts PC, et al. Induction of apoptosis by Fumonisin B1in HT29 cells is mediated by the accumulation of endogenous free sphingoid bases. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1998;148:252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith BP. Large Animal Internal Medicine. Missouri: Elsevier; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Radostits OM, Gay CC, Blood DC, Hinchcliff KW. Clínica Veterinária: Um Tratado de Doenças dos Bovinos, Ovinos, Suínos, Caprinos e Equinos, 9th ed Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2000:1770 p. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beasley VR. Equine leukoencephalomalacia/hepatosis and stachybotryotoxicosis In: Robinson NE, ed. Current Therapy in Equine Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1992, p. 377–380. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Caloni F, Cortinovis C. Effects of fusariotoxins in the equine species. Vet J 2010;186:157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sweely CC. Biochemistry of lipids and membranes In: Vance DE, e Vance JE. Biochemistry of Lipids, Lipoproteins and Membranes. Menl Park: Benjamin/Cummings Publishers; 1985: 361–403. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vandervelde M, Higgins R, Oevermann A. Veterinary Neuropathology Essentials of Theory and Practice. 1st ed Oxford: Wiley‐Blackwell; 2012: 200. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Plumlee HP, Galey FD. Neurotoxic mycotoxins: A review of fungal toxins that cause neurological disease in large animals. J Vet Intern Med 1994;8:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilson TM, Ross PF, Nelson PE. Fumonisin mycotoxins and equine leukoencephalomalacia. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991;198:1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mirocha CJ, Mackintosh CG, Mirza UA, et al. Occurrence of fumonisin in forage grass in New Zealand. Appl Environ Microbiol 1992;58:3196–3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thiel PG, Shephard GS, Sydenham EW, et al. Levels of fumonisins B1 and B2 in feeds associated with confirmed cases of equine leukoencephalomalacia. J Agric Food Chem 1991;39:109–111. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alberts JF, Gelderblom WCA, Thiel PG, et al. Effects of temperature and incubation period on production of fumonisin B1 by Fusarium moniliforme . Appl Environ Microbiol 1990;56:1729–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]