Abstract

Background

This study aimed to determine the moderating effect of personality traits on the relationship between living with an addicted man and codependency.

Methods

We selected 140 women (70 wives of addicted men and 70 wives of non-addicted men) through convenience sampling method and asked them to complete Spann-Fischer Codependency Scale and NEO-Five Factor Inventory.

Findings

Codependency score was significantly higher among addicted men’s wives. In addition, for these women, there was a strong positive correlation between codependency and neuroticism as well. Multiple regression analysis confirmed the significant interaction effects of being an addict’s wife and personality traits of neuroticism, openness and agreeableness on codependency.

Conclusion

Not all addicts’ wives experienced codependency; women with a high level of neuroticism and low level of openness and agreeableness were more vulnerable to the stress of living with an addict and to codependency.

Keywords: Addiction, Codependency, Personality

Introduction

Drug addiction is a prevalent social problem in Iranian families.1 Iran holds one of the highest rates of heroin and opium addiction per capita in the world. It is estimated that there are 2 to 4 million users out of 70 million adult population2 where approximately 50% of them are married.3

Notwithstanding, most of the Iranian addiction-related studies have focused on prevalence and etiology and only a few have examined its impacts on addicts’ family members.4

As a familial disease, addiction affects all intimate relationships and relatives of the addicted person.5 The untrustworthiness of addicts creates chaos, clutter in family and emotional confusion, and their unstable and unpredictable behaviors cause chronic anxiety, disturbance and fear within family. Family members try to control the harmful situation, blame themselves and feel shame over the circumstances. Characteristics like low self-esteem, tendency to minimize personal demands, and prioritization of others’ needs, exaggerated care taking behaviors, obsessive involvement with others and having trouble in intimate relationships are frequently reported by addicts’ families, especially their wives.6-8 These characteristics refer us to the controversial and broad concept of codependency.

The concept of codependency was initially used to define caring behaviors and relationships within family members of alcohol and drug abusers.9-11 Later it ignited debates over whether codependency is a dysfunctional relationship or a personality problem.12-15 Eventually, some studies contradicted the stereotypical view that a chemically-dependent spouse has a personality disorder making her to exhibit codependent behaviors. They instead, suggested that such behaviors are normal reactions to overwhelming stressors of living with an addict.16-19 However, what remains to determine is whether all addicts’ wives who live under distress, experience codependency, and how the role of personality should be taken into account in this regards. There is also a need to know what aspects of personality are related to codependency.

Psychologists consider personality as a unique pattern of thinking, attitude, and behavior which forms during the childhood and stays stable over the time.20-22 One of the most well-known approaches for studying personality is the five-factor model of personality. It includes neuroticism, extroversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness.23,24 According to this model, Neuroticism refers to the degree of negative emotions, insecurity, vulnerability and anxiety. Extraversion includes energy, assertiveness, sociability, and positive emotions. Agreeableness is seen as tendency to be kind and cooperative. Conscientiousness is often perceived as self-discipline, hard-working, and diligent, and openness reflects one’s curiosity, creativity and flexible outlooks.

The dominating models studding the role of personality traits in the relationship between stressor and stress show that personality not only affects how people shape stressful situation or differentially expose themselves to stressful events, but it also determines how people perceive, evaluate, cope and react to stressors.25-28 For example, in one study was shown that people who scored high in neuroticism reported more interpersonal stressors, more self-blame, wishful thinking, and more hostile reaction to cope with daily stressors. They were less confident in their coping resources for dealing with stress and used less-adaptive coping strategies.25

In light of this evidence, it may be reasonable to assume that living with an addicted man is probably perceived and experienced dissimilarly by different women depending on their personality traits. This study attempts to determine whether the wives of addicted men are different in terms of codependency and personality traits, and how personality traits affect the relationship between living with an addicted man as the stressor and codependency as its outcome.

Methods

This study was a case control research. Seventy spouses of addicted men were selected from NARAN and Congress 60 Society and 70 spouses of non-addicted men were selected from different parts of Tehran, such as metro stations and parks. Selections were carried out through convenience sampling. The population size was determined by α = 0.05, β = 0.2 and effect size = 0.5. As a result, the population size was calculated as 63 subjects in each group, but considering the risk of loss or incomplete questionnaires, 70 subjects per group were considered. Inclusion criteria for all subjects were having the ability to read and write, and signing the consent form. After providing their informed consent, subjects completed Spann-Fischer Codependency Scale (SFCS)29 and NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI).24

The study employed the SFCS for measuring codependency. This scale is composed of 16 self-reporting items with responses assessed on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Its items cover three dimensions of codependency: (1) maintaining an extreme external locus of control, (2) lacking an open expression of feelings, and (3) using order, disclaimer and rigor for building relationships. SFCS scores range from 16 to 96 with higher scores showing higher levels of codependency. Internal consistency as measured by Cronbach's alpha ranges from 0.73 to 0.80. In two administrations of the scale, stability estimations revealed a test-retest correlation of 0.87. The SFCS among other codependency scales found in literature has presented the most reliability and validity evidence.30 In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.81.

The NEO-FFI was used to evaluate five personality traits. It includes five 12-item scales developed through factor analyses as a short form of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) to assess neuroticism (N), extraversion (E), openness (O), agreeableness (A), and conscientiousness (C). The item response adopted a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree.5 For the reliability of NEO-FFI, Costa and McCrae indicated Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.86, 0.77, 0.73, 0.68, and 0.81 for N, E, O, A, and C tests respectively. For the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.70 to 0.87 for the N, E, O, A and C scales.

Pearson correlation coefficient, analysis of variances (ANOVA) and multiple regression analyses were also conducted.

Results

Thirty-eight of the women in this study (28.1%) had college education and 97 patients (71.9%) were under Postgraduate Diploma. Of all participants, 28.1% were under 30, 37% between 30 and 40 and 34.8% over 40 years of age. Fifty women (37%) were working and 85 (63%) were housewives.

Table 1 presents the mean and standard deviation of the variables. ANOVA results indicated that the codependency of addicted men’s spouses was significantly higher than that of other women (55.7 vs 51.0, P < 0.05). Mean of agreeableness in addicts’ wives was significantly higher than the wives of non-addicted (28.6 vs 26.5, P < 0.05). The other characteristics were not significantly different between the two groups of women.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation (SD) of variables

| Variable | Total | Non-drug-users’ wives | Drug-users’ wives | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 131) | (n = 67) | (n = 64) | |||

| Neuroticism | 24.9 (8.21) | 24.9 (8.32) | 24.9 (8.16) | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| Extroversion | 27.7 (5.45) | 28.1 (5.23) | 27.3 (5.68) | 0.71 | 0.40 |

| Openness | 23.8 (5.18) | 23.4 (4.65) | 24.2 (5.69) | 0.68 | 0.40 |

| Agreeableness | 27.5 (6.05) | 26.5 (6.44) | 28.6 (5.44) | 4.22 | 0.04 |

| Conscientiousness | 34.8 (6.52) | 33.8 (6.45) | 35.9 (6.49) | 3.34 | 0.07 |

| Codependency | 53.3 (12.5) | 51.0 (11.7) | 55.7 (13.1) | 4.54 | 0.03 |

The amounts are given as mean (SD).

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients between personality traits and codependency in the two groups. In drug users’ wives, neuroticism had a relatively strong and positive relationship with codependency (r = 0.62). In non-drug users’ wives, correlation of neuroticism had a positive and significant relationship with codependency (r = 0.35).

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlation matrix

| Variable | Neuroticism | Extroversion | Openness | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | Codependency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | -0.50*** | -0.18 | -0.65*** | -0.63*** | 0.35*** | |

| Extroversion | -0.42*** | 0.14 | 0.45*** | 0.54*** | -0.23 | |

| Openness | -.019 | 0.39*** | 0.11 | 0.36** | 0.23 | |

| Agreeableness | -0.47*** | 0.34** | 0.03 | 0.56*** | -0.02 | |

| Conscientiousness | -0.33** | 0.48*** | 0.32** | 0.27* | < -0.01 | |

| Codependency | 0.62*** | -0.37** | -0.16 | -0.41*** | -0.26* |

P < 0.050

P < 0.010

P < 0.001

Above the matrix: Pearson coefficients of non-drug-users’ wives; Under the matrix: Pearson coefficients of drug-users’ wives

To determine the moderating effect of personality, standardized scores of variables and hierarchical regression were performed. Group (dummy variable), personality traits and interaction of two variables were entered respectively in the first, second and third models. One of the personality traits was entered in each iteration of the regression run (totally five iterations).

Multicollinearity test was performed using the variance inflation factor to evaluate the correlation between independent variables. The average for all regression models was close to 1 indicating that multicollinearity was not a problem in the model. Multiple regression indicated a significant interaction between being a drug user’s wife and neuroticism (β = 0.23; P < 0.05, R2 = 0.03), openness (β = -0.30; P < 0.05, R2 = 0.04) and agreeableness (β = -0.29; P < 0.01, R2 = 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

The moderating effect of personality on being a drug user’s wife and codependency obtained by hierarchical multiple regression

| Predictors | B | SE B | β | R2 | R2 change | F | F change | df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||||||

| Group (1 = drug-user’s wife) | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 4.54* | 4.54* | 1129 |

| Step 2 | ||||||||

| Neuroticism | 0.49 | 0.08 | 0.48*** | 0.27 | 0.23 | 23.4*** | 40.8*** | 1128 |

| Extroversion | 0.31 | 0.08 | -0.30*** | 0.13 | 0.09 | 9.23*** | 13.5*** | 1128 |

| Openness | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 2.26 | 0.02 | 1128 |

| Agreeableness | 0.20 | 0.08 | -0.21* | 0.07 | 0.04 | 5.17** | 5.64* | 1128 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.14 | 0.08 | -0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 3.51* | 2.44 | 1128 |

| Step 3 | ||||||||

| Group * neuroticism | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.23* | 0.29 | 0.03 | 17.8*** | 5.08* | 1127 |

| Group * extroversion | -0.15 | 0.17 | -0.11 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 6.41*** | 0.78 | 1127 |

| Group * openness | -0.40 | 0.17 | -0.30* | 0.07 | 0.04 | 3.27*** | 5.14 | 1127 |

| Group * agreeableness | -0.46 | 0.17 | -0.29** | 0.12 | 0.05 | 6.04** | 7.26** | 1127 |

| Group * conscientiousness | -0.27 | 0.17 | -0.19 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 3.21* | 2.51 | 1127 |

P < 0.050

P < 0.010

P < 0.001

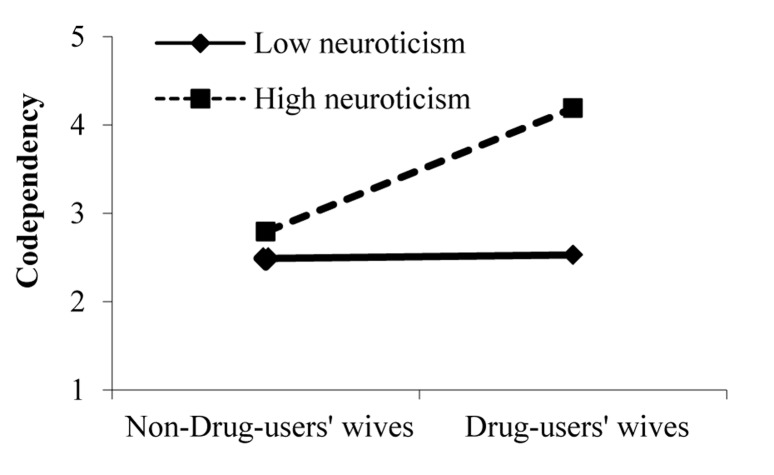

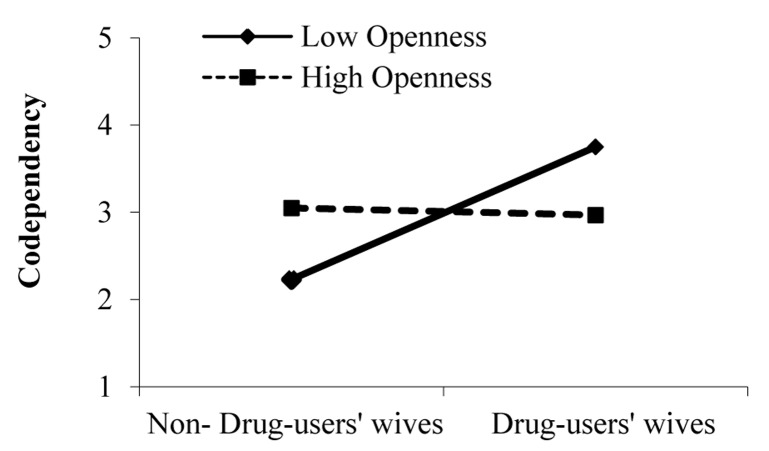

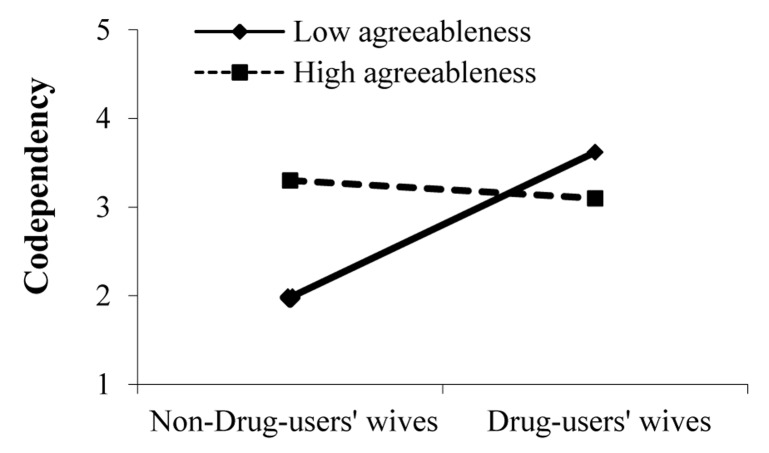

After reviewing the moderating role of personality traits in the relationship between living with an addicted man and codependency, personality traits of neuroticism, openness and agreeableness were divided into two categories. Thus, individuals whose scores were one standard deviation above the mean were placed in the high class, and those whose scores were one standard deviation below the mean were placed in the low class.

Figures 1 to 3 show that living with addicted men predicted codependency among women with high neuroticism, low openness and low agreeableness. Among women with low neuroticism, high openness and high agreeableness, being the wife of an addicted did not make a difference in the degree of codependency.

Figure 1.

The moderating effect of neuroticism on being a drug user’s wife and codependency

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of openness on being a drug user’s wife and codependency

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of agreeableness on being a drug user’s wife and codependency

Discussion

In this study, drug users’ wives had a higher codependency than those in the other group. This finding is consistent with the results obtained by some previous studies.13,31 In a study by Cermak, wives of alcoholic men compared to wives of nonalcoholic men experienced boundary distortions in situations of intimacy and separation.11 Schaef argued that addicts’ wives distort their emotions by forming codependency, neglect the turmoil of being an addict’s spouse by acceptance of duties and responsibilities, and deviate their attention from painful issues by mentally focusing on people, objects and other situations. This helps them increase their control over the situation and feel more self-worth.9

Findings revealed that except agreeableness, there were no significant differences in other personality traits in women with addicted spouses and normal women. In one study no significant difference between wives of alcoholic men and other women in terms of neuroticism and psychoticism was found, but the wives of alcoholics were less extroverted than the wives of non-alcoholics.32 However, in a small sample of wives who accompanied their husbands for treatment in Japan, wives of alcoholics were reported more neurotic.33 In another study, wives of alcoholics who had a higher profile in the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) test were highest in the hypochondriasis (Hs), depression (D) and hysteria (Hy). They were also reported to be of greatest passivity, dependence and insecurity.34

In current study, we found that wives of addicts in comparison with normal women showed higher mean of agreeableness. This finding along with evidences suggesting that addicts have low scores in agreeableness35,36 lead us to Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Model37 in which, marital quality depends on adaptive processes (e.g. spousal behaviors during difficulties) and enduring vulnerabilities (e.g. personality characteristics) against stressful events (e.g. addiction). Agreeableness was strongly associated with marital stability37 and each of the couples shall provide adequate amounts of it in their lives. To compensate for the lack of addict’s agreeableness, his wife presents a greater proportion of adaptation to maintain marital stability.

In addition, deeper attention to the nature of the agreeableness can be useful. Agreeableness is associated with trusting, altruism, caring, appeal, compliance, empathy, kindness, and cooperation.21,38,39 The high agreeableness of these women could be due to social expectations of women as caregivers and nurturers.

Correlation analysis showed that there was a relationship between neuroticism and codependency. Previous studies revealed that codependency was associated with the neuroticism dimension of personality.13 This relationship was stronger in addicts’ wives rather than normal women (0.62 to 0.36). In other words, neuroticism in wives of addicted men and normal women was predicted to be close to 40% and 13% of codependency variance, respectively. This finding was confirmed by aforementioned studies showing that absence of a goal, hopelessness, low self-esteem, failure to achieve goals, lack of confidence in the future, poor character development, and a life brimming with frustration, anxiety, depression, panic, aggression, lack of security and unpredictable environment -that are caused by unpleasant conditions of living with an addict- lead addicts’ wives to score high in neuroticism.

It is worth mentioning that both neuroticism and codependency have common symptoms. According to Hughes-Hammer and colleges, symptoms associated with codependency are hiding oneself, medical problems and low self-worth. Low self-worth includes self-criticism, self-blame and shame.31 Similarly, neuroticism includes low self-esteem, self-criticism, self-blame, guilt, emptiness, sadness, loneliness anxiety, depression, hopelessness, and lack of trust in others.23

Among women with addicted husbands, extraversion was negatively related to codependency. This result is consistent with the results obtained by other research works.13 Extraversion reflects characteristics such as sociability, being energetic, sincere, kind feelings, sensation seeking, and having positive emotions,24 while codependency associates with anxiety and depression and self-defeating characteristics.14,40

Findings revealed that living with addicts leads women who are more neurotic, less agreeable and less open to experience to exhibit codependent behaviors. In comparison with women who are low in neuroticism, individuals with higher neuroticism perceive differently and are more emotionally reactive to stressors,25,26,28,41-43 and thus use less effective coping mechanisms.25,44 Personality traits may also affect the relationship between stress and stressors through differential exposure to stressors,27,45 whereby wives of addicts who are high in neuroticism may differently expose themselves to more stressors -such as interpersonal conflicts- than those low in neuroticism.

The second moderating variable is agreeableness. Agreeable people tend to be more prosocial, generous, congenial, respectful, altruistic and gentle.22,46 They use fewer emotion-focused coping strategies,47 and are more support seeking.47,48 Furthermore, individuals who are high in agreeableness are more capable to regulate their feelings throughout interpersonal interactions, resolve conflicts and reduce the frequency and magnitude of negative interactions.39,49 Therefore, it appears that agreeableness, as a psychological resource, helps wives of addicts to cope well with life stressors and adjust their adverse effects such as codependency.

Openness to experience can be shown as “broadness, profundity, originality and intricacy of an individual’s mental and experiential life”46 as well as imagination, creativity, intelligence, and capability to learn quickly.22 Openness might be correlated with stress reduction and evaluating the situations as less threatening.38 These features allow open people to use problem-oriented coping styles and avoid using negative emotion-focused coping strategies against life stressors.44 Hence, it can be expected that, among addicts’ spouses, those who are high in openness can manage stresses of life with intelligence and be safe from the adverse consequences of such interdependence.

This study faced some limitations in design and performance. The study population was limited to wives of addicts and other family members (such as children) were omitted. Addicted individuals, who had only a history of drug abuse and consumption of alcohol, were not taken into consideration. Furthermore, the study population did not match one another in terms of month and year of participation in sessions as well as husband’s addiction history. The small population size and the convenience sampling make it difficult to generalize the results to the entire population. The control effects of some probable confounding variables such as husbands’ mental health, codependency in women’s family of origin and current family relationships and dynamics were not taken into consideration.

Conclusion

From what mentioned, it can be concluded that not all addicts’ spouses experienced codependency. Women under stress of living with addicts were high in neuroticism and low in openness and agreeableness, probably because they perceive the situation more stressful and use less effective coping strategies; then, they will be vulnerable against the stressors and experience codependency, as the consequence of these circumstances.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the women participated in this research.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zarghami M. Iranian common attitude toward opium consumption. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2015;9(3):e2074. doi: 10.17795/ijpbs2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MOKRI A. Brief overview of the status of drug abuse in Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2002;5(3):184–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joolaee S, Fereidooni Z, Seyed Fatemi N, Meshkibaf MH, Mirlashari J. Exploring needs and expectations of spouses of addicted men in Iran: a qualitative study. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;6(5):132–41. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n5p132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohammad Khani P, Asgari A, Frouzan SA, Moumeni F, Delavar B. The expression of psychiatric symptoms among women with addicted husbands. Dev Psychol. 2010;6(23):237–45. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham AV, Berolzheimer N, Burge S. Alcohol abuse. A family disease. Prim Care. 1993;20(1):121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uhle SM. Codependence: contextual variables in the language of social pathology. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1994;15(3):307–17. doi: 10.3109/01612849409009392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Brien PE, Gaborit M. Codependency: a disorder separate from chemical dependency. J Clin Psychol. 1992;48(1):129–36. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199201)48:1<129::aid-jclp2270480118>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenny ME, Donaldson GA. Contributions of parental attachment and family structure to the social and psychological functioning of first-year college students. J Couns Psychol. 1991;34(4):479–86. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wegscheider-Cruse S. Choice-making: for co-dependents, adult children, and spirituality seekers. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaef AW. Co-Dependence: misunderstood-mistreated. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cermak TL. Diagnostic criteria for codependency. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1986;18(1):15–20. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1986.10524475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright PH, Wright KD. Codependency: Addictive love, adjustive relating, or both? Contemp Fam Ther. 1991;13(5):435–54. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gotham HJ, Sher KJ. Do codependent traits involve more than basic dimensions of personality and psychopathology? J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57(1):34–9. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wells M, Glickauf-Hughes C, Brass K. The Relationship of Co-Dependency to Enduring Personality Characteristics. J College Stud Psychother. 1998;12(3):25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martsolf DS. Codependency, boundaries, and professional nurse caring: understanding similarities and differences in nursing practice. Orthopaedic Nursing: 2002;21(6):61–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asher R, Brissett D. Codependency: a view from women married to alcoholics. Int J Addict. 1988;23(4):331–50. doi: 10.3109/10826088809039202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson SC. A critical analysis of the concept of codependency. Soc Work. 1994;39(6):677–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller KJ. The co-dependency concept: does it offer a solution for the spouses of alcoholics? J Subst Abuse Treat. 1994;11(4):339–45. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hands M, Dear G. Co-dependency: a critical review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1994;13(4):437–45. doi: 10.1080/09595239400185571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barenbaum NB, Winter DG. Personality. In: Freedheim DK, Weiner IB, editors. Handbook of psychology, history of psychology. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg LR. The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychol Assessment. 1992;4(1):26–42. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL. Personality development: stability and change. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:453–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Domains and facets: hierarchical personality assessment using the revised NEO personality inventory. J Pers Assess. 1995;64(1):21–50. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychol Assessment. 1992;4(1):5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunthert KC, Cohen LH, Armeli S. The role of neuroticism in daily stress and coping. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(5):1087–100. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engelhard Iris M, van den Hout Marcel A, Kindt M. The relationship between neuroticism, pre-traumatic stress, and post-traumatic stress: a prospective study. Pers Indiv Differ. 2003;35(2):381–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolger N, Zuckerman A. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(5):890–902. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider Tamera R. The role of neuroticism on psychological and physiological stress responses. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2004;40(6):795–804. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer JL, Spann L. Measuring codependency. Alcohol Treat Q. 1991;8(1):87–100. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allison S. Nurse codependency: instrument development and validation. J Nurs Meas. 2004;12(1):63–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes-Hammer C, Martsolf DS, Zeller RA. Development and testing of the codependency assessment tool. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1998;12(5):264–72. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(98)80036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grubisic-Ilic M, Ljubin T, Kozaric-Kovacic D. Personality dimensions and psychiatric treatment of alcoholics' wives. Croat Med J. 1998;39(1):49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okazaki N, Fujita S, Suzuki K, Niimi Y, Mizutani Y, Kohno H. Comparative study of health problems between wives of alcoholics and control wives. Arukoru Kenkyuto Yakubutsu Ison. 1994;29(1):23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Avila-Escribano JJ, Ledesma Jimeno A. Personality study of wives of alcoholic patients. Actas Luso-Espanolas de Neurologia, Psiquiatria y Ciencias Afines. 1990;18(6):355–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. The relations among personality, symptoms of alcohol and marijuana abuse, and symptoms of comorbid psychopathology: results from a community sample. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;10(4):425–34. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Rooke SE, Schutte NS. Alcohol involvement and the Five-Factor model of personality: a meta-analysis. J Drug Educ. 2007;37(3):277–94. doi: 10.2190/DE.37.3.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: a review of theory, method, and research. Psychol Bull. 1995;118(1):3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakker AB, Van der, Lewig KA, Dollard MF. The relationship between the Big Five personality factors and burnout: a study among volunteer counselors. J Soc Psychol. 2006;146(1):31–50. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.146.1.31-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen-Campbell LA, Graziano WG. Agreeableness as a moderator of interpersonal conflict. J Pers. 2001;69(2):323–61. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roehling PV, Gaumond E. Reliability and validity of the codependent questionnaire. Alcohol Treat Q. 1996;14(1):85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kennedy DK, Hughes BM. The optimism-neuroticism question: an evaluation based on cardiovascular reactivity in female college students. Psychol Rec. 2004;54(3):373. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santed MA, Sandin B, Chorot P, Olmedo M, Garcia-Campay J. The role of negative and positive affectivity on perceived stress-subjective health relationships. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2003;15(4):199–216. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5215.2003.00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vollrath M. Personality and hassles among university students: a three-year longitudinal study. Eur J Pers. 2000;14(3):199–216. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Besharat MA. Personality and coping styles. Journal of Psychology. 2007;2(7):25–49. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spector PE, Zapf D, Chen PY, Frese M. Why negative affectivity should not be controlled in job stress research: don't throw out the baby with the bath water. J Organ Behav. 2000;21(1):79–95. [Google Scholar]

- 46.John OP, Srivastava S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson D, Hubbard B. Adaptational style and dispositional structure: coping in the context of the five-factor model. J Pers. 1996;64(4):737–74. [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Brien TB, DeLongis A. The interactional context of problem-, emotion-, and relationship-focused coping: the role of the big five personality factors. J Pers. 1996;64(4):775–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graziano WG, Tobin RM. Agreeableness: dimension of personality or social desirability artifact? J Pers. 2002;70(5):695–727. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.05021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]