Abstract

Acute hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection is a leading cause of acute liver failure (ALF) in many developing countries yet rarely identified in Western countries. Since antibody testing for HEV infection is not routinely obtained, we hypothesized that HEV-related ALF might be present and unrecognized in North American ALF patients. Serum samples of 681 adults enrolled in the US ALF Study Group were tested for anti-HEV IgM and anti-HEV IgG levels. Subjects with a detectable anti-HEV IgM also underwent testing for HEV-RNA. Mean patient age was 41.8 years, 32.9% male, and ALF etiologies included acetaminophen hepatotoxicity (29%), indeterminate ALF (23%), idiosyncratic DILI (22%), acute HBV infection (12%), autoimmune hepatitis (12%) and pregnancy related ALF (2%). Three men ages 36, 39, and 70 demonstrated repeatedly detectable anti-HEV IgM but all were HEV RNA negative and had other putative diagnoses. The latter two subjects died within 3 and 11 days of enrollment while the 36 year old underwent emergency liver transplantation on study day 2. At admission, 294 (43.4%) of the ALF patients were anti-HEV IgG positive with the seroprevalence being highest in those from the Midwest (50%) and lowest in those from the Southeast (28%). Anti-HEV IgG + subjects were significantly older, less likely to have APAP overdose, and had a lower overall 3 week survival compared to anti-HEV IgG − subjects (63% vs 70%, p= 0.018).

CONCLUSIONS

Acute HEV infection is very rare in adult Americans with ALF (i.e., 0.4%) and could not be implicated in any indeterminate, autoimmune, or pregnancy-related ALF cases. Prior exposure to HEV with detectable anti-HEV IgG was significantly more common in the ALF patients compared to the general US population.

Keywords: Viral hepatitis, zoonoses, liver transplant, fulminant hepatitis, occult

Introduction

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is an enterically transmitted single stranded RNA virus that is a common cause of sporadic hepatitis in India and other tropical countries (1). The diagnosis of acute HEV infection requires the detection of anti-HEV IgM or HEV RNA in the serum or stool of an affected patient or the development of anti-HEV IgG within 6 to 12 months in a patient who was previously seronegative (1, 2). However, only 50 to 66% of symptomatic patients with acute HEV infection have detectable HEV RNA in the blood (1, 2). In endemic areas, acute HEV is most commonly attributed to infection with HEV genotype 1 or 2 and has been associated with the development of acute liver failure (ALF) particularly in pregnant women (3, 4). Subjects with underlying chronic liver disease may also develop acute on chronic liver failure following acute HEV infection (5, 6).

Acute HEV infection is rarely encountered in most developed countries unless someone has a history of travel to an endemic area like Asia or Africa (2, 7, 8). However, as many as 20% of individuals in the general US population have detectable anti-HEV IgG indicative of prior exposure with no antecedent history of hepatitis suggesting prior subclinical infection (9). Acute symptomatic HEV infection in developed nations is believed to be a zoonosis wherein HEV genotype 3 is transmitted to humans through consumption of undercooked pork or wild game (10). Recent reports from the United Kingdom and Australia suggest that acute sporadic HEV infection may account for 5 to 10% of presumed drug induced liver injury (DILI) cases (11, 12). The US Drug Induced Liver Injury Network also demonstrated that 9 of 318 (3%) consecutive patients with suspected DILI were actually likely due to acute HEV, since all were anti-HEV IgM positive and 4 had detectable HEV RNA in their blood (13).

The US Acute Liver Failure Study Group (ALFSG) is a consortium of academic medical centers that has been studying the etiologies and outcomes of adult patients with ALF for the past 18 years (14). Etiologies identified include acetaminophen (APAP) hepatotoxicity (46%) idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury (DILI) (10%), autoimmune hepatitis (7%), hepatitis B virus (7%) and various other etiologies. Despite extensive testing for identifiable causes of ALF with highly sensitive molecular diagnostic assays, imaging, and histological analysis, roughly 10% of adult ALFSG patients have no identifiable cause of ALF and remain “indeterminate”. Prior studies in indeterminate ALF patients looking for occult herpes simplex virus, SEN virus, hepatitis B, and parvovirus infections have been unrevealing (15–17). In the current study, we tested sera from a large cohort of adult patients to determine the presence of previously unrecognized acute HEV infection in indeterminate, autoimmune, HBV, DILI, and pregnancy related ALF. In addition, we examined the seroprevalence of prior HEV infection defined as detectable anti-HEV IgG in consecutive patients. Our final aim was to determine if any subjects with acute HEV infection or those who have undergone liver transplantation have evidence of chronic HEV infection in long-term follow-up serum samples.

Patients and Methods

ALFSG study protocol

This consortium of academic medical centers, funded by the National Institutes of Health, has continued an ongoing prospective observational study of consecutive ALF patients seen at their centers since 1998 (14). The study group administrative center is at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas) with the data coordinating center at the Medical University of South Carolina (Charleston, South Carolina). Eligible patients have symptoms of new onset jaundice or hepatitis of less than 26 weeks prior to admission and mental status changes with coagulopathy defined as an international normalized ratio (INR) > 1.5 without known underlying chronic liver disease. In addition to baseline demographics and presenting features, detailed information during the first seven days of enrollment including imaging, lab, and clinical data, as well as outcome data are obtained through 21 days after admission. In addition, long term clinical data collected at one and two years after enrollment are available in patients enrolled after 2000 (18). Blood samples are also collected from participants at enrollment and for 7 consecutive days as well as at long-term follow-up study visits. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of participating sites and written informed consent was obtained from the next of kin of eligible patients due to their impaired mental status. The current study protocol to analyze de-identified serum samples and data was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Michigan and at the NIH.

HEV testing

Day 1 sera (or the earliest day with available serum) from ALF patients randomly selected from those enrolled between 1998 to July, 2011 had been stored at −80° C prior to shipment for testing for anti-HEV IgM and anti-HEV IgG. The anti-HEV IgM, anti-HEV IgG, and HEV-RNA testing were completed in the CLIA-certified research lab of Dr. Robert Purcell at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). A modification of the ELISA assay previously described was used to test all samples for anti-HEV IgG using 10 ul of serum in duplicate and positive controls were run on each plate (19). In addition, anti-HEV IgM was detected using a class-capture ELISA assay using 10 ul of serum in duplicate (20, 21). All samples that were positive for anti-HEV IgM using the ELISA assay were also tested using the Wantai HEV IgM Elisa (Wantai, Beijing) which has superior sensitivity in some studies (22, 23). An independent serum sample was also tested for HEV RNA, using consensus primers, from a 140 ul sample of serum by real-time PCR (24). The lower limit of detection of the HEV RNA test was 50 genome equivalents (GE)/reaction or 3.3 log10 GE/ml. For patients with an indeterminate anti-HEV IgG test results (i.e. within 10% of the cutoff), a serum sample was retested using a confirmatory IgG blocking test but we could not confirm the presence of detectable anti-HEV IgG. Of note, all 18 patients with indeterminate anti-HEV IgG test results were anti-HEV IgM negative. Available long-term follow-up serum samples from patients with an initial anti-HEV IgG positive sample underwent testing for anti-HEV IgM and quantitative anti-HEV IgG titers.

Acute HEV infection was defined as a patient with anti-HEV IgM + on repeated testing with or without HEV RNA + or a patient with repeatedly positive HEV RNA, independent of anti-HEV IgM and IgG levels. Prior exposure to HEV infection was defined as a patient with anti-HEV IgG + alone (i.e. anti-HEV IgM (−)).

Data analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A population of 678 subjects with definitive anti-HEV IgG test results was analyzed using descriptive statistics to characterize demographics and other clinical variables describing illness severity, treatment, and outcomes. Differences between the anti-HEV IgG positive and negative test result groups were tested using the Student's t-test for continuous measures, the chi-square test for categorical measures, and the Fisher's exact test for categorical measures with expected cell sizes less than five. All tests were assessed at the 0.05 significance level. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine if the probability of testing anti-HEV IgG positive was affected by pre-specified prognostic variables.

Results

Acute HEV infection

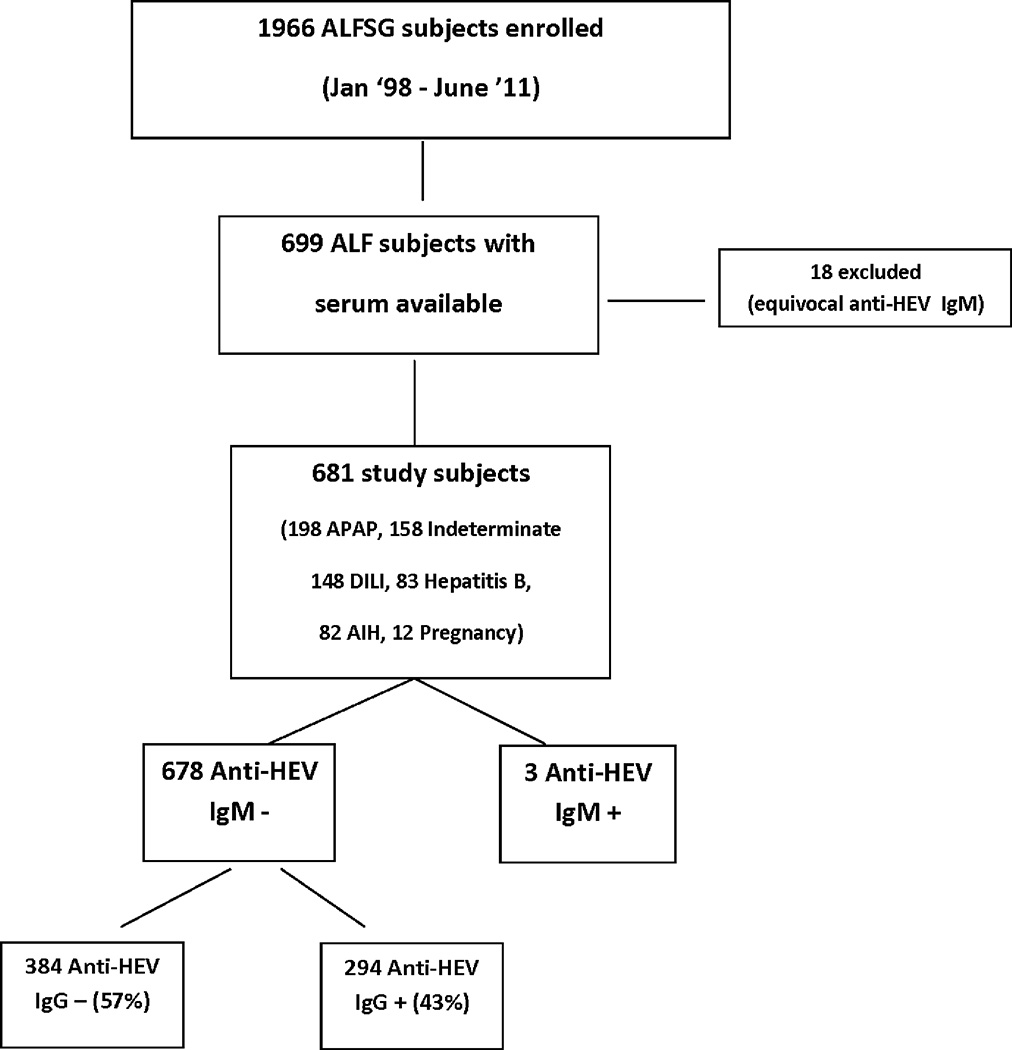

Between January 1998 and July 2011, serum samples from 699 eligible patients were available for testing of anti-HEV IgM and anti-HEV IgG levels. In 18 patients, anti-HEV IgG test results were indeterminate even on repeat testing, possibly due to IgG levels below the detection limit of the assay or the presence of interfering substances. The etiology of ALF, age, gender HE grade, and frequency of blood transfusions prior to and after enrollment was not significantly different from those with interpretable results (data not shown) and all of these patients were anti-HEV IgM negative. Therefore, for this analysis only the results of 681 patients with a positive or negative value for anti-HEV IgM are included (Figure 1). Overall, only 3 of the 681 patients (0.4%) tested persistently positive for anti-HEV IgM. However, follow-up testing of 8 independent serum samples in these 3 patients failed to demonstrate any detectable HEV RNA. These 3 male Caucasian patients were enrolled with ALF initially attributed to alternative etiologies as summarized below.

Figure 1. Overview of study population.

Of the 699 ALFSG patients with serum that was tested for anti-HEV IgM, 681 had interpretable anti-HEV IgM results. There were 3 subjects who were repeatedly anti-HEV IgM + and anti-HEV IgG + as well. Among the 678 anti-HEV IgM − subjects, there were 56% who were anti-HEV IgG − and 44% anti-HEV IgG +.

Case #1

A 71 year old Caucasian male with hyperlipidemia and atherosclerotic heart and carotid disease presented to a midwestern hospital in 2004 with a 6 week history of malaise, fever, and progressive weakness with jaundice. His initial biochemical findings included serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 1868 IU/l, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 2724 IU/l, and bilirubin of 10.4 mg/dl. A transjugular liver biopsy showed lobular necroinflammatory activity with necrotic hepatocytes and predominance of plasma cells in the portal tracts attributed to presumed atorvastatin hepatotoxicity (Figure 2). After discharge, he was rehospitalized 10 days later for altered mental status with a serum ALT of 128 U/L and bilirubin of 2.5 mg/dl. Medications at presentation included famotidine, questran, aspirin, a multivitamin and atorvastatin 10 mg per day that he had been on for 2 months. At study enrollment, he had normal vital signs, grade 1 encephalopathy, mild leg edema and ascites. Labs at study enrollment included a white blood cell count (WBC) of 6.4 × 103/ml, hemoglobin 8.9 g/dl, platelets 35 × 103/ml, serum creatinine of 3.3 mg/dl and a pH of 7.23/21/70 on 60% oxygen. His serum ALT was 62 U/L, AST 89 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 152 U/L with a total bilirubin of 40.5 mg/dl and INR of 1.6. Testing for anti-HAV IgM, HBsAg, anti-HBc IgM, and anti-HCV were all negative as was liver imaging and a urine toxicology screen.

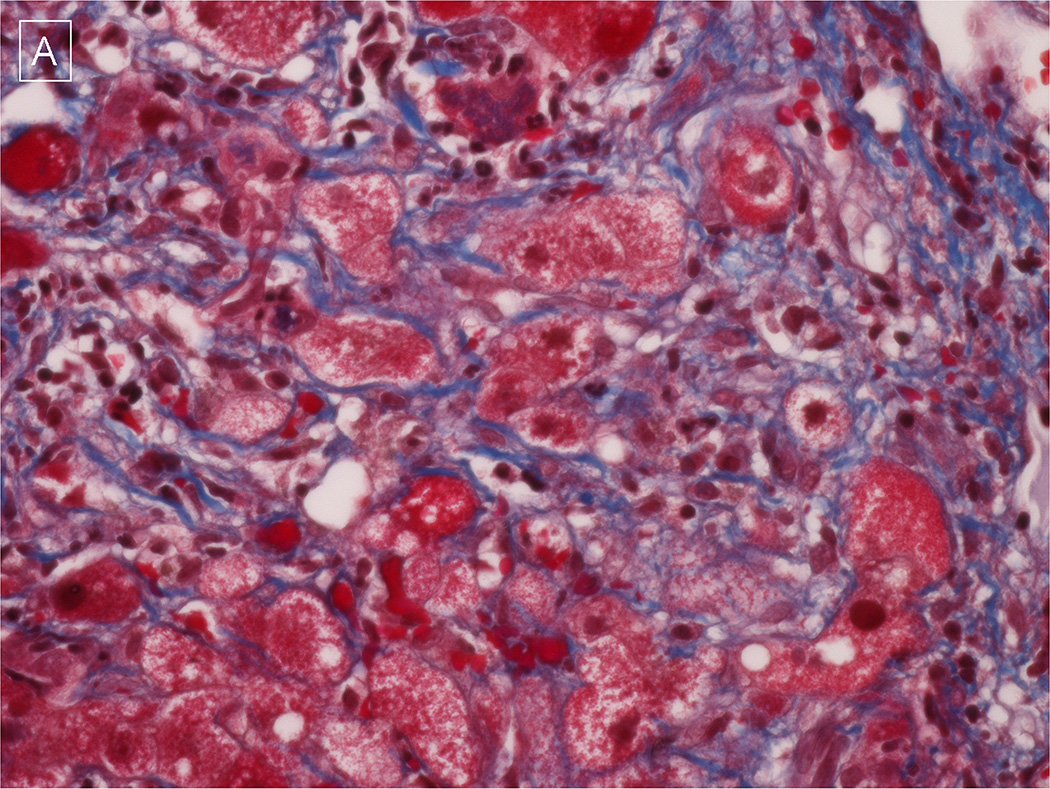

Figure 2. Representative liver histopathology from an acute HEV patient.

A & B) A transjugular liver biopsy demonstrates bridging and chicken-wire fibrosis as well as Mallory bodies on trichrome stain suggestive of antecedent non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (400 × magnification). Photomicrograph provided by Dr. Lan Peng of University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas.

Despite supportive measures, he deteriorated with a peak bilirubin of 45 mg/dl and he required intubation and hemodialysis. He died of cardiac arrest on study day #11 and no autopsy was performed. His initial study day #2 serum samples were strongly positive for anti-HEV IgM and were confirmed with testing of independent study day #2 and #3 serum samples. His initial anti-HEV IgG titer was also strongly positive but HEV RNA was repeatedly negative.

Case #2

This 36 year old Caucasian male presented with 4 days of nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain to a Northeastern hospital in 2006. The patient reported a history of depression, migraines, and prior spinal fusion for which he had been receiving acetaminophen-oxycodone for the past month as well as losartan/hydrochlorothiazide, esomeprazole, wellbutrin, and valium. At study day #1, he had a blood pressure of 171/101 and grade IV encephalopathy with hyper-reflexia and was intubated. His WBC was 4.3 × 103/ml, hemoglobin 13.4 g/dl and platelets 112 × 103/ml and creatinine 5.6 mg/dl. His serum AST was 1858 U/L, ALT 1866 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 103 U/L with total bilirubin 12.8 mg/dl and INR 5.3. At presentation, his serum APAP level was not detected and urine tox screen was positive for benzodiazepenes and opiates. Diagnostic studies including anti-HAV IgM, anti-HCV, HCV RNA by PCR, and anti-HIV as well as anti-nuclear and smooth-muscle antibodies were all negative. His initial local HBsAg was positive, but anti-HBc IgM, HBeAg and HBV DNA were negative or not detected. No blood products had been given prior to the day 1 serum sample.

The patient was intubated, had an intracranial pressure monitor placed and underwent emergency liver transplantation on study day #2. His explant pathology showed submassive zone 2 and 3 necrosis and there was severe cholestasis both intra-hepatocytic and canalicular with extensive formation of ductular hepatocytes and a prominent ductular reaction. HBV core and surface antigen immunostains were negative. At a long-term follow-up study visit 31 months after enrollment, he was doing well and had normal liver biochemistries. He was not receiving any antivirals for HBV and was only on mycophenolate, amlodipine, and metoprolol. His initial study day #1 anti-HEV IgM was positive on first testing but repeat testing of study days #1 and additional samples from study day #2 were negative. Testing of study day #1 and 2 samples using the Wantai kit was positive in 2 of 3 instances for anti-HEV IgM. Initial anti-HEV IgG was strongly positive but his month 31 serum sample was anti-HEV IgG negative.

Repeat testing of study day #1 stored serum at NIAID failed to demonstrate any detectable HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HCV, or anti-HDV using standard ELISA assays. In addition, HBV DNA and HCV RNA were not detectable by PCR. However, a study day #1 serum sample did have detectable serum cysteine-APAP adducts with a level of 1.73 nmoles/ml (Normal: < 1.0 nmole/ml). Therefore, the initial clinical diagnosis of “indeterminate” ALF was incorrect and this patient’s clinical course was more consistent with inadvertent APAP hepatotoxicity and possible concomitant acute HEV infection (21). However, the lack of persistent anti-HEV IgG during follow-up makes the latter diagnosis less likely.

Case #3

This 39 year old Caucasian male presented with a 2 week history of nausea, malaise, and jaundice in 2008. The patient had a history of crack cocaine use and depression. He was receiving no medications and denied any recent travel. At study enrollment, he had a temperature of 38.2° C, blood pressure of 109/63, ascites on exam and was intubated with grade IV encephalopathy and evidence of cerebral edema by head CT. His initial WBC was 11.5 × 103/ml, hemoglobin 12.9 g/dl, and platelets 106 × 103/ml with a serum creatinine of 2.1 mg/dl. His initial serum AST was 257 U/L, ALT 295 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 95 UL, and total bilirubin 24.6 mg/dl with INR of 8.8. His serum APAP level was undetectable and anti-HAV IgM, anti-HCV, and HCV RNA were all negative. However, his serum tested positive for HBsAg + and anti-HBc IgM + and plasma HBV DNA titer was 6,610 IU/ml. Local testing for HIV, anti-HDV, ANA, and SmAb and HBeAg were not done. The patient was treated with supportive care and placed on lamivudine; he was not listed for liver transplant due to active substance abuse. He died on study day 3 of multi-organ failure and an autopsy was not performed.

Initial anti-HEV IgG testing from study days #1 and 2 was strongly positive as was study day #1 serum for anti-HEV IgM. However, repeat testing of independent day 1 and 2 samples were negative. Testing of independent study day #1 and 2 samples using the more sensitive Wantai kit showed that one of two was anti-HEV IgM + and other sample was borderline positive as well. Repeat testing of his study day #1 serum for anti-HBc (IgM) was strongly positive with a signal/noise ratio of 83 suggesting acute HBV infection. He did not receive blood products after study day #1.

Seroprevalence of prior HEV infection

Overall, 294 of the 678 patients (43.4%) without acute HEV infection were anti-HEV IgG positive. Individuals with detectable anti-HEV IgG were significantly older and more likely to be non-Caucasian (Table 1). In addition, they had a longer mean duration of symptoms prior to presentation and were significantly more likely to have had a non-APAP etiology of ALF with lower serum ALT levels. The anti-HEV IgG seropositive patients were more likely to have grade 3–4 encephalopathy at admission and to undergo liver transplantation and not surprisingly their overall survival at 3 weeks after enrollment was significantly lower (63% vs 70%, p=0.018). The anti-HEV IgG + patients were also more likely to have received blood products both prior to and after study enrollment. Assessment of the year enrollment demonstrated that the proportion of anti-HEV IgG + cases significantly decreased over time (p=0.0198, Cochran- Armitage test) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 1.

Presenting features and outcomes of ALF patients with detectable versus undetectable anti-HEV IgG at enrollment

| Anti-HEV IgG (−) N=384 |

Anti-HEV IgG (+) N=294 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 40 + 14 | 44 + 15 | 0.001 |

| % Male | 32% | 33% | 0.72 |

| % Caucasian | 77% | 67% | 0.003 |

| % African American | 16% | 19% | |

| % Other | 7% | 14% | |

| % Hispanic | 12% | 9% | 0.332 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28 + 7 | 28 + 7 | 0.988 |

| Symptoms to enrollment (d) | 15 + 19 | 19 + 21 | 0.009 |

| Etiology of ALF | |||

| % Acetaminophen | 35% | 22% | 0.0002 |

| % Non-Acetaminophen | 65% | 78% | |

| Initial ALT (IU/ml) | 2782 + 3490 | 2203 + 2796 | 0.017 |

| Initial Alkaline phos (IU/ml) | 175 + 132 | 179 + 141 | 0.715 |

| Initial Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 15 + 12 | 17 + 12 | 0.014 |

| INR | 3.8 + 2.7 | 3.7 + 3.5 | 0.727 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 2.1 + 1.9 | 2.0 + 1.6 | 0.741 |

| % Grade ¾ Encephalopathy | 42% | 55% | 0.0008 |

| % Hemodialysis/ CVVH | 30% | 30% | 0.83 |

| % Intubated | 56% | 63% | 0.069 |

| Outcomes at 3 weeks * | |||

| % Alive | 71% | 63% | 0.018 |

| % Died | 29% | 37% | |

| % Transplanted at 3 weeks | 29% | 35% | 0.086 |

| % Transfusion pre-enrollment | 40% | 56% | < 0.0001 |

| % Transfusion post-enrollment | 67% | 78% | 0.001 |

Data presented as mean + std deviation or %

7 subjects were lost to follow-up with missing outcome data

A multivariate logistic regression model was constructed to identify independent predictors of anti-HEV IgG + serostatus (Table 2). Patients with non-APAP etiologies, older individuals, recipients of a blood product transfusion prior to enrollment, earlier year of enrollment and those with grade ¾ encephalopathy were significantly more likely to be anti-HEV IgG positive. The c-statistic for the model was 0.660.

Table 2.

Multivariate model of predictors of anti-HEV IgG positive ALF patients

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Non-APAP etiology | 1.92 (1.34, 2.77) | 0.0005 |

| Grade 3/4 HE at admission | 1.57 (1.12, 2.19) | 0.0081 |

| Blood transfusion pre-study | 1.87 (1.34, 2.61) | 0.0003 |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.19 (1.07, 1.33) | 0.0034 |

| Year of enrollment | 0.95 (0.90, 0.99) | 0.0190 |

Seroprevalence of anti-HEV IgG in ALF patients compared to US population controls

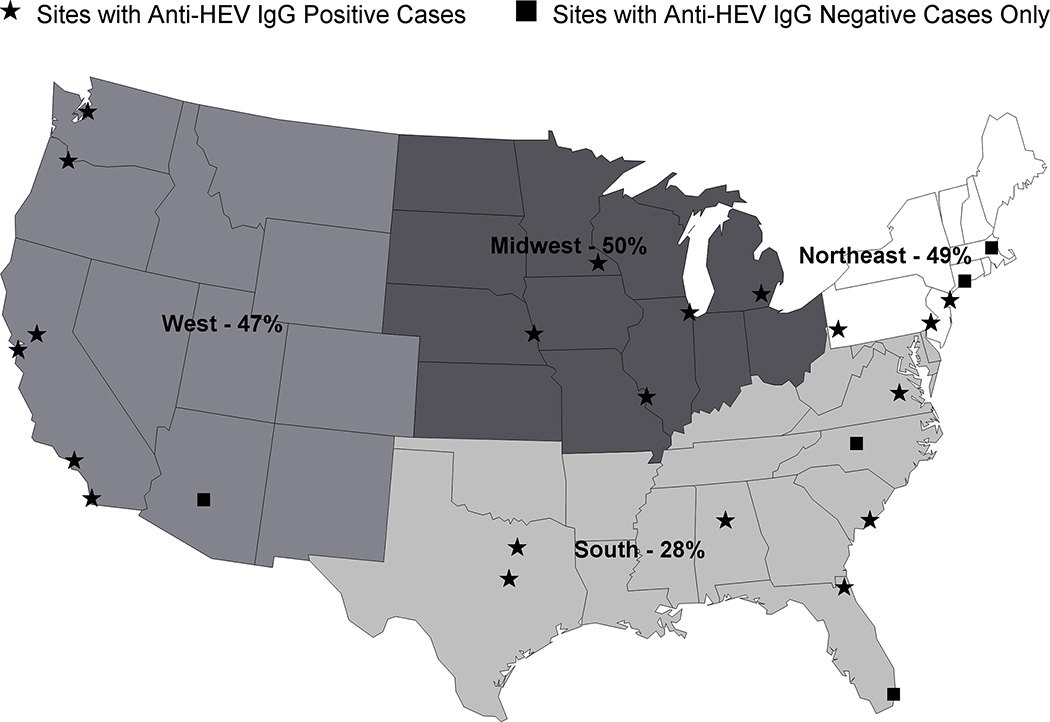

A prior study using the same assay demonstrated that the seroprevalence of anti-HEV IgG in the United States was in part related to subject age, gender, and geographical location (7). The proportion of anti-HEV IgG positive patients in our cohort was significantly higher than that reported in the general US population of 18, 695 individuals (43.4% vs 21.0%, p< 0.0001, chi-square) but we were unable to control for differences in participant age and gender. In our cohort, the region of the country where the patient was enrolled was a strong correlate of anti-HEV IgG seropositivity with subjects enrolled in the Southeast being least likely to be anti-HEV IgG positive compared to those from other regions (Figure 3). Amongst the 28 individual sites that contributed cases, the highest seroprevalence for anti-HEV IgG was noted in Nebraska (77%) and the lowest was reported in Alabama (17%) and Arizona (0%). Analyses exploring seasonal or longitudinal trends over time with anti-HEV IgG serostatus did not identify a relationship (data not shown).

Figure 3. Seroprevalence of anti-HEV IgG + ALF patients by site location.

There were 28 sites in the US ALFSG who contributed samples to this study over a 13 year period. When the frequency of anti-HEV IgG + samples was analyzed by geographic location, patients enrolled in the 8 southeastern sites had a statistically significantly lower seroprevalence rate compared to the other regions of the US (28% vs 48% p < 0.001).

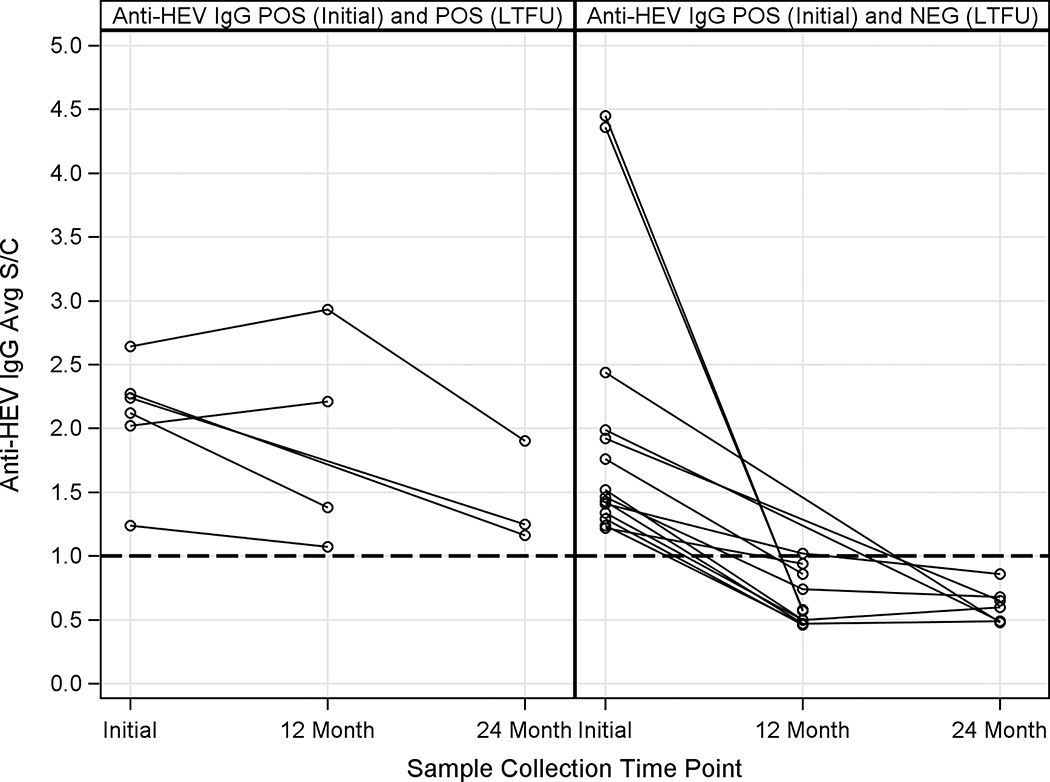

Persistence of Anti-HEV IgG levels during follow-up

Amongst the 294 anti-HEV IgG + patients, long-term follow-up serum samples were available for repeat testing in 20 subjects at a median of 19.6 months after initial enrollment. As shown in Figure 4, 6 of the 20 patients had persistently detectable anti-HEV IgG levels while 14 patients lost their antibody over time. Neither the initial anti-HEV IgG titer nor use of blood products prior to ALF enrollment were associated with persistence of anti-HEV IgG levels over time (data not shown).

Figure 4. Initial and follow-up anti-HEV IgG levels in ALF patients over time.

A) There were 6 patients with a positive anti-HEV IgG baseline serum sample that remained positive at their month 12 and or month 24 study visit. B) There were 14 patients who also had a positive anti-HEV IgG baseline serum sample that became negative with a level of < 1.0 at their month 12 or 24 study visit. POS= Positive NEG= Negative

Discussion

Previous reports from the ALF Study Group have demonstrated that a sizable proportion (11%) of adult Americans with ALF are of indeterminate etiology (14). Many of these patients present with a viral prodrome of malaise, fever, and fatigue over several weeks yet testing for occult viral infections has been repeatedly negative (15–17). However, as many as 18% of these indeterminate ALF patients have detectable serum acetaminophen-protein adducts which indicate that they likely were misclassified and could have potentially benefited from n-acetylcysteine therapy (25). Even if a small proportion of the indeterminate ALF patients had undiagnosed acute HEV infection this could have important epidemiological implications as well as clinical implications for the patients undergoing liver transplantation. It is also important to determine if some DILI related ALF cases are actually due to acute HEV infection since DILI is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion and prior studies have demonstrated a significant frequency of acute HEV infection in these patients (11–13). Identification of HEV infection in pregnant women with ALF is also of interest since prior studies have suggested that acute HEV infection may be more severe in pregnant patients and associated with substantial maternal and fetal mortality (3, 4). Testing for occult HEV infection with known or suspected fulminant HBV infection is of interest since acute on chronic liver failure has been previously reported in patients with chronic HBV and HEV superinfection (5, 6). Finally, we tested patients with presumed autoimmune ALF since this diagnosis is notoriously difficult to establish and empiric use of steroids could be detrimental if the patients actually had unsuspected acute HEV infection (26).

In the current study, only 3 of the 681 (0.4%) ALF patients tested had detectable anti-HEV IgM and none of these had detectable HEV RNA despite the acute nature of their presentations. These data indicate that previously unsuspected acute HEV infection is exceedingly uncommon in American adults presenting with ALF. The 3 patients who tested anti-HEV IgM positive were all non-Hispanic, Caucasian men and two of the cases originated from a single center in the Northeast, but were separated in time by 2 years. In the United States, sporadic cases of severe acute HEV infection have been reported by the Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) as well as by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (13, 27). Interestingly, 8 of the 9 cases in DILIN arose in older men with a mean age of 69 but none of the patients had overt risk factors for acquiring HEV infection such as eating undercooked pork or wild game (13). The initial cause of ALF in our 3 patients included DILI attributed to atorvastatin (Case #1), APAP overdose (case #2), and fulminant HBV (case #3). The absence of detectable HEV RNA in all 3 of our ALF cases was unexpected since prior series of severe acute HEV genotype 1 infection from India have demonstrated readily detectable HEV RNA in 60 to 80% of patients and 4 of the 9 DILIN patients had detectable HEV RNA (4, 13). Nonetheless, the liver histopathology in case #1 was consistent with the pattern of liver damage reported in prior cases of acute HEV. However, the histological pattern of liver injury in case #2 was more consistent with APAP related liver injury with prominent pericentral necrosis. The detection of a high level of serum APAP-protein adducts in this patients case suggest that the patient likely had unrecognized acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in addition to possible acute HEV infection. Case #3 was also a complex individual who had evidence of acute HBV infection with possible acute HEV as well. In addition, stool samples and fresh frozen liver tissue were not available for PCR testing to confirm the presence of replicating HEV infection at the time of ALF onset in any of our patients. Furthermore, specially prepared sera for growth of HEV in tissue culture were also not available. Testing of convalescent sera was only possible in case #2 and interestingly anti-HEV IgG was no longer detectable during prolonged follow-up. Of note, this LT recipient did not develop evidence of chronic hepatitis or chronic HEV infection which has been previously reported in other solid organ transplant recipients who had detectable HEV-RNA pre-transplant (28–30). In addition, more recent studies from France have demonstrated that up to 40% of HEV RNA + solid organ transplant recipients will spontaneously clear HEV RNA within 2 years of transplant (31).

A large proportion of our cohort was anti-HEV IgG positive (43.4%) (Table 2). This rate is significantly higher than the seroprevalence of prior HEV infection reported in a large population based study done using the same assay (43.4% vs 21.0%, p < 0.0001) (9). In the prior study, the seroprevalence of HEV infection was consistently higher in men compared to women and increased in both genders with age suggesting that immunity to HEV may be acquired over time via environmental exposure despite the absence of clinical hepatitis. Of note, pigs and wild game are known reservoirs of HEV genotype 3 infection in the US and Germany (10, 32). Consumption of undercooked organ meats and pork has been associated with zoonotic transmission of HEV to humans (33). Furthermore, all of the cases of acute sporadic hepatitis in western patients from the US, UK, and France have been attributed to HEV genotype 3 infection and not HEV genotype 1 or 2 infection (2). Our data demonstrated a higher seroprevalence of anti-HEV IgG in older versus younger ALF patients similar to population studies. In addition, there were remarkable geographic similarities of anti-HEV IgG seroprevalence in our cohort compared to the general US population with the highest rates noted in ALF patients from the Midwest (50%) and the lowest in those from the southeast (28%). Lastly, the proportion of patients with detectable anti-HEV IgG declined over time during the study period from 1998 to 2011 (supplementary Figure 1). Other studies have also noted a decline in the prevalence of anti-HEV IgG positive blood donors and individuals in the general population using the same assay (23, 36). The reason for the declining seroprevalance in western patients over time is unknown but a consistent finding

Since 20 to 30% of healthy blood donors have detectable anti-HEV IgG, it is possible that the high sero-prevalence of anti-HEV IgG in our cohort may be due to passive transfer of antibody from blood products given prior to their study enrollment. Since fresh frozen plasma acquired from multiple donors is frequently required for ALF patients undergoing procedures and as many as 20% of healthy blood donors have detectable anti-HEV IgG, some of the ALF patients may have simply acquired detectable anti-HEV through transfusion (34).

In 2004, we tested sera of 126 ALF indeterminate patients for occult HEV infection using a PCR assay for HEV RNA and anti-HEV IgM and IgG levels using an ELISA assay based upon two recombinant antigens derived from a Burmese isolate of HEV (17). Although 11 patient samples demonstrated some reactivity to one or more HEV peptides, none of them demonstrated any detectable HEV RNA and the pattern of IgM results was inconsistent, suggestive of false positive test results. Overall, the current set of data appears to be more accurate and reliable due to the high level of reproducibility achieved with this assay in multiple laboratories (34, 35). In addition, there was a high degree of concordance of our data with data generated by the Wantai assay that was used in a limited number of these cases as well. Recent studies have demonstrated that an alternative ELISA assay may have superior sensitivity and specificity compared to the assay used in our study but additional studies are needed (23, 36). Limitations of our study include the lack of testing fresh frozen tissue or stool samples at the time of ALF presentation for HEV RNA which is known to be more sensitive than serum HEV RNA testing. In addition, stored frozen sera were used for this study which could have led to analyte degradation during prolonged storage. However, prior studies done by the authors have demonstrated durable anti-HEV IgM and anti-HEV IgG levels with repeated freeze thaw cycles and prolonged cold storage (20).

In summary, these data demonstrate that previously unsuspected acute HEV infection is an exceedingly uncommon cause of ALF in the United States. Furthermore, unsuspected acute HEV infection was not implicated in any of the indeterminate, pregnancy, nor autoimmune related ALF patients, and classic HEV RNA positive ALF was not recognized in any of our patients. The lack of detectable HEV RNA in all 3 of the anti-HEV IgM positive cases makes it difficult to know if the acute HEV infection was the primary or secondary reason for ALF and whether it was important at all or simply represented a false positive IgM test in a patient with perhaps recently past inapparent infection. Case #1 had evidence of underlying steatohepatitis and was confounded by statin use. Case #2 likely had a component of liver injury from acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and case #3 had presumed concomitant acute HBV infection. In addition, the absence of stool and fresh liver tissues did not allow us to confirm the presence of replicating HEV genotype 3 infection. Finally, no identifiable risk factor such as travel to an endemic area or ingestion of undercooked pork or organ meats could be identified in these 3 case patients. Despite these limitations, we feel that it is more likely than not that acute HEV infection played some role in all 3 cases. The high seroprevalence of anti-HEV IgG in our study mirrors the age, gender, and geographic distribution of prior HEV infection reported in population based studies of HEV in the United States using the same assay. Subjects with anti-HEV IgG had a significantly lower 3- week survival and a greater need for emergency liver transplantation compared to the anti-HEV IgG negative patients which may be due to their higher rate of non-APAP related ALF as well as their increased age (14, 18).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Lan Peng of University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas for providing photomicrographs. Members and institutions participating in the Acute Liver Failure Study Group 1998-2011 are as follows: W.M. Lee, M.D. (Principal Investigator), George A. Ostapowicz, M.D., Frank V. Schiødt, M.D., Julie Polson, M.D., University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX; Anne M. Larson, M.D., Iris Liou, M.D., University of Washington, Seattle, WA; Timothy Davern, M.D., University of California, San Francisco, CA (current address: California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco, CA), Oren Fix, M.D., University of California, San Francisco; Michael Schilsky, M.D., Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY (current address: Yale University, New Haven, CT); Timothy McCashland, M.D., University of Nebraska, Omaha, NE; J. Eileen Hay, M.B.B.S., Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN; Natalie Murray, M.D., Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, TX; A. Obaid S. Shaikh, M.D., University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; Andres Blei, M.D., Northwestern University, Chicago, IL (deceased), Daniel Ganger, M.D., Northwestern University, Chicago, IL; Atif Zaman, M.D., University of Oregon, Portland, OR; Steven H.B. Han, M.D., University of California, Los Angeles, CA; Robert Fontana, M.D., University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI; Brendan McGuire, M.D., University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL; Raymond T. Chung, M.D., Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA; Alastair Smith, M.B., Ch.B., Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC; Robert Brown, M.D., Cornell/Columbia University, New York, NY; Jeffrey Crippin, M.D., Washington University, St Louis, MO; Edwyn Harrison, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ; Adrian Reuben, M.B.B.S., Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC; Santiago Munoz, M.D., Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA; Rajender Reddy, M.D., University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA; R. Todd Stravitz, M.D., Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA; Lorenzo Rossaro, M.D., University of California Davis, Sacramento, CA; Raj Satyanarayana, M.D., Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL; and Tarek Hassanein, M.D., University of California, San Diego, CA. The University of Texas Southwestern Administrative Group included Grace Samuel, Ezmina Lalani, Carla Pezzia, and Corron Sanders, Ph.D., Nahid Attar, the Statistics and Data Management Group included Joan S. Reisch, Ph.D., Linda S. Hynan, Ph.D., Janet P. Smith, Joe W. Webster and Mechelle Murray, and the Medical University of South Carolina Data Coordination Unit included Valerie Durkalski, Ph.D., Wenle Zhao, Ph.D., Catherine Dillon, and Tomoko Goddard.

Grant support: We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the members of The Acute Liver Failure Study Group. This study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK U-01-58369). Additional funding provided by the Tips Fund of Northwestern Medical Foundation and the Jeanne Roberts and Rollin and Mary Ella King Funds of the Southwestern Medical Foundation. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Abbreviations

- ALF

Acute Liver Failure

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- APAP

Acetaminophen

- BMI

Body mass index

- CDC

Center for Disease control

- DILI

Drug induced liver injury

- DILIN

Drug Induced Liver Injury Network

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HEV

Hepatitis E virus

- INR

International normalized ratio

- NIAID

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

- NIDDK

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- WBC

White blood count

Contributor Information

Ronald E. Engle, Email: RENGLE@niaid.nih.gov.

Steven Scaglione, Email: sscagli@lumc.edu.

Victor Araya, Email: victorarayamd@gmail.com.

Obaid Shaikh, Email: obaid@pitt.edu.

Holly Tillman, Email: tillmanh@musc.edu.

Nahid Attar, Email: Nahid.attar@utsouthwestern.edu.

Robert H. Purcell, Email: roberthpurcell@gmail.com.

William M. Lee, Email: William.lee@utsouthwestern.edu.

References

- 1.Purcell RH, Emerson SU. Hepatitis E: an emerging awareness of an old disease. J Hepatology. 2008;48:494–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoofnagle JH, Nelson KE, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E. NEJM. 2012;367:1237–1244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1204512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patra S, et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnant women with acute hepatitis E virus infection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:28–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kar P, Jilani N, Husain SA, Pasha ST, Anand R, Rai A, Das BC. Does Hepatitis E viral load and genotypes influence the final outcome of acute liver failure during pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2495–2501. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acharya SK, et al. Hepatitis E virus infection in patients with cirrhosis is associated with rapid decompensation and death. J Hepatology. 2007;46:387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamid SS, Atiq M, Shehzad F, Yasmeen A, Nissa T, Salam A, Siddiqui A, Jafri W. Hepatitis E virus superinfection in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2002;36:474–478. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peron E. Fulminant liver failure from acute authochthonous hepatitis E in France: description of seven patients with acute hepatitis E and encephalopathy. J Viral Hep. 2007;15:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manka P, Bechmann LP, Coombes JD, Thodou V, Schlattjan M, Kahraman A, et al. Hepatitis E virus infection as a possible cause of acute liver failure in Europe. Clin Gastro Hep. 2015;13:1836–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuniholm MH, Purcell RH, McQuillan GM, Engle RE, Wasley A, Nelson KE. Epidemiology of hepatitis E virus in the United States: results from the Third NHANES, survey, 1988–1994. J Infec Dis. 2009;200:48–56. doi: 10.1086/599319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wichmann O, Schimanski S, Koch J, et al. Phylogenetic and case control study on hepatitis E virus infection in Germany. JID. 2008;198:1732–1741. doi: 10.1086/593211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalton HR, Fellows HJ, Stableforth W, Joseph M, et al. The role of hepatitis E virus testing in drug-induced liver Injury. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1429–1435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalton HR, Fellows HJ, Gane E, Wong P, Gerred S, Schroeder B, et al. Hepatitis E in New Zealand. J Gastro Hepatol. 2007;22:1236–1240. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davern TJ, Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, et al. Acute hepatitis E infection accounts for some cases of suspected drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1665–1672. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiodt FV, Larson A, Davern TJ, Han SHB, et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947–954. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levitsky J, Duddempudi AT, Lakeman FD, Whitley RJ, Luby JP, Lee WM, et al. Detection and diagnosis of herpes simplex virus infection in adults with acute liver failure. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:1498–1504. doi: 10.1002/lt.21567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umemura T, Tanaka E, Ostapowicz G, Brown KE, Heringlake S, Tassopoulos NC, et al. Investigation of SEN virus infection in patients with cryptogenic acute liver failure, hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia, or acute and chronic non-A-E hepatitis. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;188:1545–1552. doi: 10.1086/379216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee WM, Brown KE, Young NS, Dawson GJ, Schlauder GG, Gutierrez RA, et al. Brief report: no evidence for parvovirus B19 or hepatitis E virus as a cause of acute liver failure. Digest Dis Sci. 2006;51:1712–1715. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-9061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rangnekar AS, Ellerbe C, Durkalski V, McGuire B, Lee WM, Fontana RJ. Quality of life is significantly impaired in long-term survivors of acute liver failure and particularly in Acetaminophen overdose patients. Liver Transplantation. 2013;19:991–1000. doi: 10.1002/lt.23688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engle RE, Yu C, Emerson SU, Meng XJ, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E virus capsid antigens derived from viruses of human and swine origine are equally efficient for detecting anti-HEV by enzyme immunoassay. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4576–4580. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4576-4580.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu C, Engle RE, Bryan JP, Emerson SU, Purcell RH. Detection of immunoglobulin M antibodies to hepatitis E virus by class capture enzyme immunoassay. Clin Diag Lab Immun. 2003;10:579–586. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.4.579-586.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bendall R, Ellis V, Ijaz S, Ali R, Dalton H. A comparison of two commercially available anti-HEV IgG kits and a reevaluation of anti-HEV IgG seroprevalence data in developed countries. J. Med Virol. 2010;82:799–805. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pas SD, Streefkerk RH, Pronk M, de Man RA, Beersma MF, Osterhaus AD, et al. Diagnostic performance of selected commercial HEV IgM and IgG ELISA’s for immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. J Clin Virology. 2013;58:629–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holm DK, Moessner BK, Engle RE, Zaaijer HL, Georgsen J, Purcell RH, et al. Declining prevalence of hepatitis E antibodies among Danish Blood Donors Transfusion. 2015;55:1662–1667. doi: 10.1111/trf.13028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shukla P, Nguyen HT, Torian U, Engle RE, Faulk K, Dalton HR, et al. Cross-species infections of cultured cells by hepatitis E virus and discovery of an infectious virus-host recombinant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2438–2443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018878108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khandelwal N, James LP, Sanders C, Larson AM, Lee WM. Unrecognized acetaminophen toxicity as a cause of indeterminate acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2011;53:567–576. doi: 10.1002/hep.24060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stravitz TR, Lefkowitch JH, Fontana RJ, Gershwin ME, Leung PSC, Sterling RK, et al. Autoimmune acute liver failure: Proposed clinical and histological criteria. Hepatology. 2011;53:517–526. doi: 10.1002/hep.24080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drobeniuc J, Greene-Montfort T, Le NT, Mixson-Hayden TR, Ganova-Raeva L, Dong C, et al. Laboratory based surveillance for hepatitis E virus infection, United States, 2005–2012. Emer Inf Dis. 2013;19:218–222. doi: 10.3201/eid1902.120961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamar N, Selves J, Mansuy JM, et al. Hepatitis E virus and chronic hepatitis in organ-transplant recipients. NEJM. 2008;358:811–817. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haagsma EB, Niesters HG, Van den berg AP, Riezebos-Brilman A, Porte RJ, Vennema H, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis E virus infection in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transplantation. 2009;15:149–150. doi: 10.1002/lt.21819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamar N, Abravanel F, Selves J, et al. Influence of immunosuppressive therapy on the natural history of genotype 3 hepatitis E virus infection after organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2010;89:353–359. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181c4096c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamar N, Legrand-Abravanel F, Izopet J, Rostaing L. Hepatitis E virus: what transplant physicians should know. AJT. 2012;12:2281–2287. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng XJ, Purcell RH, Halbur PEG, et al. A novel virus in swine is closely related to the human hepatitis E virus. PNAS. 1997;94:9860–9865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson KE, Kmush B, Labrique AB. The epidemiology of hepatitis E virus infections in developed countries and among immunocompromised patients. Expert Reviews. 2011;9:133–1148. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meng XJ, Wiseman B, Elvinger F, et al. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis E virus in veterinarians working with swine and in normal blood donors in the United States and other countries. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:117–122. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.1.117-122.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mast EE, Alter MJ, Holland PV, Purcell RH. Evaluation of assays for antibody to hepatitis E virus by a serum panel. Hepatitis E Virus Antibody Serum Panel Evaluation Group. Hepatology. 1998;27(3):857–861. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ditah I, Ditah F, Devaki P, Ditah C, Kamath PS, Charlton M. Current Epidemiology of hepatitis E virus infection in the United States: Low seroprevalence in the National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey. Hepatology. 2014;64:815–822. doi: 10.1002/hep.27219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.