Abstract

Turner Syndrome (TS) is a developmental disorder caused by partial or complete loss of one sex chromosome. Bicuspid aortic valve and other left-sided congenital heart lesions (LSL), including thoracic aortic aneurysms and acute aortic dissections, are 30-50 times more frequent in TS than in the general population. In 454 TS subjects, we found that LSL are significantly associated with reduced dosage of Xp genes and increased dosage of Xq genes. We also showed that genome-wide copy number variation is increased in TS and identify a common copy number variant (CNV) in chromosome 12p13.31 that is associated with LSL with an odds ratio of 3.7. This CNV contains three protein-coding genes (SLC2A3, SLC2A14 and NANOGP1) and was previously implicated in congenital heart defects in the 22q11 deletion syndrome. In addition, we identified a subset of rare and recurrent CNVs that are also enriched in non-syndromic BAV cases. These observations support our hypothesis that X chromosome and autosomal variants affecting cardiac developmental genes may interact to cause the increased prevalence of LSL in TS.

Keywords: Genomics, Turner Syndrome, Valvular Heart Disease, Congenital Heart Defects, X chromosome

INTRODUCTION

Turner Syndrome (TS) is a developmental disorder caused by partial or complete loss of one sex chromosome and occurs in approximately 1 in 2500 female births. Girls and women with TS present with diverse developmental defects, including short stature, webbed neck, skeletal abnormalities, premature ovarian failure and cardiovascular malformations [Bondy, 2007]. Approximately half of TS patients have a single X chromosome in all peripheral blood lymphocytes. Other TS patients have a mosaic arrangement of 45,X and 46,XX cells or structural derivatives that include isochromosomes, rings and deletions [Carlson and Silberbach, 2009; Prakash et al., 2014]. The severity of TS features are generally correlated with the percentage of cells that harbor a single copy of Xp, but only one gene has been implicated in a specific phenotypic feature of TS: decreased expression of the SHOX gene in the pseudoautosomal region of Xp is associated with short stature and skeletal deformities [Rao et al., 1997].

The prevalence of bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) is 30-50 times higher in TS women than in the general population (0.5-1.0%) [Matura et al., 2007]. More than one-third of TS patients have a BAV, and approximately half of these patients also have coarctation of the aorta, aortic dilation and an increased risk of acute aortic dissection in comparison with non-TS BAV patients. Thoracic aortic aneurysms and aortic dissections (TAAD) are recognized as a major cause of morbidity and mortality in TS women, and the vast majority of aortic dissections in TS occur in women with BAV [Carlson et al., 2012]. Therefore, understanding the genetic basis of BAV could lead to improved surveillance and targeted therapies to prevent deaths from acute dissections in TS.

Current insight into the genetic causes of non-syndromic BAV is limited and is primarily derived from linkage studies of familial cases. Those studies suggest multifactorial inheritance with reduced penetrance and variable phenotypes typical of complex diseases [Cripe et al., 2004]. Because BAV is more frequently observed in 45,XO females (>30%) and 46,XY males (2%) than in 46,XX females (0.5%), reduced dosage of X chromosome gene(s) that escape X inactivation is hypothesized to contribute to BAV and other TS phenotypes [Bondy et al., 2013]. Males may be partially protected from BAV by paralogous Y chromosome gene(s) with compensatory developmental functions [Bellott et al., 2014]. We hypothesize that TS patients are uniquely predisposed to BAV due to the combination of two genetic ‘hits’: copy variation of X chromosome gene(s) and other common genetic variants that modify susceptibility to BAV. These genetic variants may also contribute to BAV in the general population, which is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality from TAAD and valve degeneration.

The X chromosome genes responsible for congenital heart defects in TS have not been identified, and the lack of a suitable animal model for TS has been a significant limitation. The absence of overt TS phenotypes in female mice with a single X chromosome may be attributable to differences in X inactivation or X chromosome gene content between mice and humans [Omoe and Endo, 1994]. The purpose of this collaborative genomic study was to investigate the effect of X chromosome gene content and common variation on congenital heart defects in TS women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston granted permission for this work (protocols HSC-MS-07-0399 and HSC-MS-01-251). Included subjects were non-Hispanic patients of European descent with a diagnosis of TS from our institution, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, Partners HealthCare, Boston MA, Second University of Naples, Italy, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the National Registry of Genetically Triggered Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Other Cardiovascular Conditions (GenTAC) [Kroner et al., 2011]. The institutional IRBs approved the studies at these sites, and participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Samples and clinical data were de-identified to preserve patient confidentiality.

In all subjects, the diagnosis of TS was confirmed by karyotype analysis and/or sex chromosome microarray genotypes [Prakash et al., 2014]. Subjects without a confirmed diagnosis of TS were excluded. Aortic measurements and BAV morphologies were classified according to published criteria. [Matura et al., 2007; Schaefer et al., 2008]. Association tests of left-sided lesions (LSL) were restricted to BAV and aortic coarctation; data on other LSL types was incomplete and therefore were not analyzed.

The GenTAC Imaging Core Laboratory (ICore) reported valve morphologies and aortic measurements on a total of 364 echocardiograms from 184 of the 275 (67%) GenTAC TS subjects (Figure S1, Supplementary Online Material). ICore was unable to determine aortic valve morphology with confidence in 29 subjects (11%) due to poor image quality or absence of preoperative images for analysis. An additional 91 subjects had no images in ICore. In the 120 GenTAC subjects without interpretable ICore images, LSL diagnoses were determined from clinical records. At other sites, diagnoses were directly confirmed by specialists with clinical expertise in cardiac imaging.

DNA extraction, sample quantitation and genotyping were performed as described [Prakash et al., 2014]. 436 of 454 samples passed quality assessments and were selected for genotyping. Allele detection and genotype calling were performed in the GenomeStudio genotyping module (v 2011.1, Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA) using updated manifests in the hg19 genome build with 716,503 SNPs (manifest humanomniexpress-24v1-0_a, 196 samples) or 730,525 SNPs (manifest humanomniexpress-12v1_j, 229 samples). Duplicate samples (n=13) and samples with genotypes that were not consistent with TS (n=11) were excluded. To equalize SNP densities between cases and controls, the control Omni 2.5 panels (2,379,855 SNPs) were filtered to select only the subset of SNPs that overlap with OmniExpress arrays (704,517) prior to the analysis. Samples that did not cluster with HapMap CEU (Utah residents with ancestry from Northern and Western Europe) samples in multidimensional scaling analysis, excess heterozygosity, excess homozygosity or more than 2% missing genotypes (n=10) were excluded from further analysis. SNPs with call frequency < 0.98, cluster separation < 0.25 or heterozygote excess < −0.5 or >0.5 (n=7) were also excluded. The concordance between four unintentional sets of duplicate samples was > 98%. After exclusions, 395 of 412 eligible genotypes passed quality controls and were available for association tests.

Copy number variants (CNVs) were identified using three algorithms: CNVPartition (v. 3.6.1, Illumina, Inc.) Nexus Copy Number (v. 7.5, Biodiscovery, Inc., Hawthorne, CA) and PennCNV (v. 2011) [Wang et al., 2007].. CNVs with fewer than six contiguous probes, CNVs less than 20 kilobases in length or CNVs greater than 5 megabases in length were excluded. For Nexus analysis, the SNPRank algorithm was used with significance threshold of 1×10−8, default gender set to female and systematic correction based on array type. Sample-level quality control analysis was performed using PennCNV. Samples were excluded from further analysis if any of the following criteria were met: Log R Ratio (LRR) standard deviation > 0.35 for autosomes or 0.45 for the X chromosome, B Allele Frequency (BAF) drift > 0.1, waviness factor > 0.05 or number of CNVs identified > 2 standard deviations above the mean of each dataset. CNVs in immunoglobulin, pericentromeric and subtelomeric regions and regions with allelic imbalance or loss of heterozygosity were also excluded. The frequencies at which genotypes were excluded were not significantly different between datasets.

To deduce X chromosome structures, DNA copy number and percent mosaicism were calculated using BAF and LRR values for 18,239 SNPs along the length of the X chromosome. Non-mosaic 45,X genotypes were identified by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) across the entire X chromosome. BAF values were also used to determine the number of haplotypes present in isochromosome cell lines and map crossover events. Calculation of percent mosaicism for X and Y chromosome SNPs was based on the deviation of allele frequencies from expected values for copy losses or copy gains according to published methods. To deduce the most likely genotypes and estimate the percentages of mosaic cell lines, we compared mean BAF and LRR values of segmental aneuploidies to expected values for monosomies and trisomies.

We used the ‘cnv-detect-no-overlap’ function in PLINK (v 1.07) to identify CNVs that were called by at least two algorithms and merged the output of all pairwise comparisons into a single file. We then combined these overlapping CNV calls with the highest-confidence CNVs from CNVPartition (confidence score > 250) and PennCNV (log Bayes factor > 75) to generate the final CNV lists for analysis. CNVs with fewer than three total occurrences in cases and controls were classified as rare CNVs. CNV Regions (CNVRs) were defined as the intersection of overlapping CNV calls, and CNVRs with at least 50% overlap were considered to be recurrent. CNV annotation functions in PLINK (--cnv-freq and --cnv-report-regions) were used to determine CNV frequencies and to identify genes within TAAD-associated CNVs. Gene lists were then compared to identify recurrent CNVs within and across groups using standard Unix functions. Gene enrichment in rare CNVs was determined using methods derived from Raychaudhuri et al., and burden tests were permuted to generate empiric P-values [Raychaudhuri et al., 2010]. The burdens of deletions and duplications were analyzed separately. Case-control comparisons of individual CNVRs were evaluated using Fisher exact tests. For functional analysis, gene lists were entered into the ToppGene Analysis Suite to generate permuted P values for enriched pathways and functions [Chen et al., 2007]. All candidate CNVs were manually reviewed and verified in GenomeStudio.

To identify recurrent CNVs, TS genotypes were systematically compared with CNV data from five cohorts with BAV and TAAD: 480 subjects with sporadic BAV (BAV) who were enrolled at Partners HealthCare, 805 sporadic TAAD cases (STAAD), affected probands from families with inherited TAAD (FTAAD, n=96) or left ventricular outflow tract obstructive defects (LVOTO, n=1651), 109 subjects with early onset TAAD (ETAAD), as well as control Illumina genotypes of 18,897 subjects in four cohorts obtained from the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGAP, Table S1, Supplementary Online Material). The characteristics of the STAAD and FTAAD cohorts were previously described [Prakash et al., 2010; LeMaire et al., 2011]. The enrollment criteria for ETAAD and STAAD subjects were identical, except that ETAAD subjects were younger (less than 31 years old at enrollment). LVOTO subjects were enrolled at four sites: Texas Children's Hospital (TCH) in Houston, Texas, Nationwide Children's Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, Children's Hospital in Linz, Austria and Primary Children's Hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah, under the respective IRB-approved protocols at each institution. Families enrolled at Houston and Columbus are an extension of a previously reported cohort [Lewin et al., 2004; McBride et al., 2009]. Patients were eligible if they had a left-sided cardiac developmental defect (aortic valve stenosis, with or without a bicuspid aortic valve, coarctation of the aorta, hypoplastic left heart syndrome or mitral stenosis) without evidence of extra-cardiac involvement (non-dysmorphic, non-syndromic, no other congenital anomalies). Diagnoses were confirmed by echocardiography, cardiac catheterization or direct observation at cardiac surgery. Our analysis was confined to unrelated individuals of European descent from each dataset. Phenotypic data relevant to TAAD were not available from any of the dbGAP samples.

Genome-wide associations of single SNPs with LSLs were analyzed in PLINK, using logistic regression with the first two principal components as covariates [LeMaire et al., 2011]. Study power was analyzed using the GAS Power Calculator (http://csg.sph.umich.edu//abecasis/cats/gas_power_calculator/index.html).

Copy number data were independently validated using quantitative real-time PCR with customized TaqMan copy number assay kits according to the manufacturer's protocols (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Foster City, CA). Reactions were run on a Vii A7 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 6-8 replicates and analyzed using Sequence Detection Software. Relative copy number was calculated from Ct values using a custom Excel spreadsheet.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the TS cohort are presented in Table I. There was no significant difference in age or body size between individuals with LSL (BAV and/or coarctation, n=187) and those without LSL (n=237). The overall prevalence of BAV was 41% (178/430) and was highly enriched in subjects with coarctation (65/78, 84%) and previous surgical repair of ascending or root aneurysms (85/114, 75%). Five of the six subjects who developed acute aortic dissections (1.4% of cohort) had BAV. Aortic valve morphology was determined in 126 (68%) GenTAC subjects, including 61 BAV cases. In 307 cases with available data, a clinical history of lymphedema was strongly associated with BAV (OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.5-5.1, P=0.002) and coarctation (OR 3.1, 95% CI 2.1-7.1, P<0.001). The physical feature that was most highly correlated with BAV was a webbed neck (OR 3.9, 95% CI 2.4-6.4, P<0.001). These observations corroborate previous data suggesting that lymphedema involving the torso may reflect an underlying disruption of cardiac outflow tract development.

Table I.

Characteristics of 430 Cases in Study Cohort

| n or median | % or IQR | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26.2 | 15-42 |

| BSA (kg/m2) | 1.48 | 1.22-1.67 |

| BAV | 176 | 41 |

| Coarct | 78 | 18 |

| BAV+Coarct | 65 | 15 |

| Aortic Dilation | 104 | 24 |

IQR: interquartile range; BSA: body surface area; BAV: bicuspid aortic valve, with or without coarctation; Coarct: coarctation of the aorta, with or without BAV; Aortic Dilation: aortic size index (ascending aortic diameter indexed to body surface area) > 20 mm/m2. Study sample was derived from 454 total cases after exclusion of duplicates (n=13) and non-TS genotypes (n=11). Data on BAV (n=420), Coarct (n=417) and Aortic Dilation (n=290) were not available for all subjects.

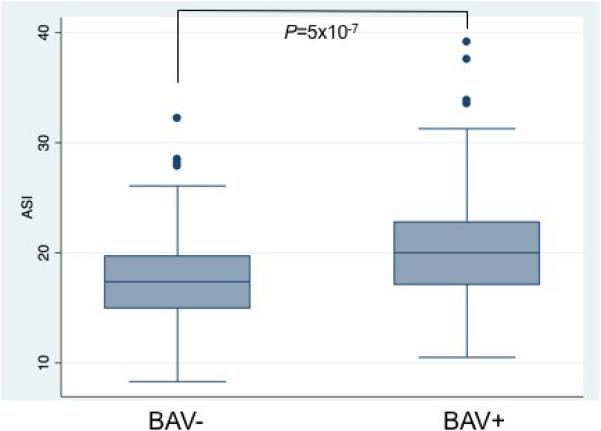

Native or pre-operative aortic diameters of the ascending aorta were available for 292 TS cases (68%). Significant ascending aortic dilation, as assessed by the ratio of ascending aortic diameter to body surface area, was greater than 20 mm/m2 in 104 (35%) cases. Indexed aortic diameters were significantly larger in TS subjects with BAV (20.5mm/m2, 95% CI 19.7-21.4 mm/m2) than in TS subjects without BAV (17.9 mm/m2, 95% CI 17.3-18.5 mm/m2, P=5.0×10−7, Figure 1). However, diameters at the sinuses of Valsalva (n=201) and sinotubular junction (n=173) were not significantly larger in BAV subjects. We did not detect significant differences in aortic diameters between BAV subjects with right-left coronary cusp fusion (n=49), right-non-coronary cusp fusion (n=8) and unicommisural aortic valves (n=4). There were no significant differences in aortic diameters at any level in subjects with coarctation. Mean aortic diameters were also not significantly different between subjects with 45,X and mosaic karyotypes.

Figure 1. Larger Ascending Aortic Diameters in Subjects with BAV.

Box-and- whisker plots of the aortic size index (ASI), the maximum diameter of the ascending aorta divided by body surface area (mm/m2), stratified by the presence (+) or absence (−) of bicuspid aortic valve (BAV). Levene's test verified equal variances.

The distribution of X chromosome structural variants is summarized in Table II. The majority of peripheral blood karyotypes were 45,X (67%) or mosaic with 45,X and 46,X,i(Xq) cell lines (15%). Y material was detectable in 26 subjects (6%), including 17 who had intact Y chromosomes (45,X;46,X,Y mosaics) and 9 who had Y structural variants. The presence of Y material was not independently associated with LSL (P=0.2). As previously reported, the 45,X karyotype is strongly associated with LSL in TS. BAV was observed in 52% of 45,X TS subjects and in 24% of all other subjects (OR 3.6, 95% CI 1.4-9.1, chi-squared P=3.4×10−8). There was no significant correlation between the estimated fraction of 45,X cells in the peripheral blood of mosaic subjects and the prevalence of BAV or coarctation. LSL were less prevalent in subjects with mosaic isochromosomes (45,X;46,X,i(Xq), 30%) and were not observed in any of 13 subjects with non-mosaic isochromosomes (46,X,i(Xq)). In aggregate analysis, the inverse relationship between Xq dosage and LSL was highly significant (chi-squared P<1×10−6). These observations indicate that increased dosage of Xq gene(s) may protect against LSL.

Table II.

Prevalence of X chromosome structural variants

| Genotype | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 45,X | 281 (67) |

| 46,X,del(Xp) | 11 (3) |

| 46,X,iso(Xq) | 14 (3) |

| 45,X;46,X,iso(Xq) | 61 (15) |

| 45,X;46,X,der(X) | 16 (4) |

| 45,X;46,X,X | 33 (8) |

| Total | 416 (100) |

Del: deletion; iso: isochromosome; der: derivative. None of the 26 subjects with Y material had X structural variants, compared with 109/390 (27%) of subjects without Y material (P=0.002).

LSL were present in 3 of 11 subjects (27%) with non-mosaic Xp deletions. The most distal breakpoint in an Xp deletion subject with BAV, who also had coarctation, was mapped to 10,043,000 bp, within WWC3 in Xp22.2. This deletion results in a single copy of Pseudo-Autosomal Region 1 and 21 protein-coding genes. The other two breakpoints in LSL cases were both proximal to Xp11.3 (44,718,785 bp). We conclude that, in rare cases, distal Xp deletions may be sufficient to cause BAV.

In association studies comparing TS subjects with BAV (n=161) or any LSL (n=173) to TS subjects without LSL (n=213), no single nucleotide variant (SNP) attained genome-wide significance (P<5×10−8). No X chromosome SNPs were significantly associated with LSL. Thus, we were unable to detect a significant modifying effect of common autosomal SNPs on the risk of LSL in TS. However, post-hoc analysis demonstrated that our study was significantly underpowered to detect genome-wide associations (23% power for alleles with a relative risk of 1.5, the maximum effect size that we observed).

Using CNV association tests, we compared the burden of CNVs in TS cases, other cohorts with BAV and TAAD, and unselected dbGAP controls. Surprisingly, the prevalence of large genic autosomal CNVs and the proportion of TS subjects with very rare CNVs (28%) were consistently increased in TS cases (Table III) and were comparable to early onset (ETAAD) TAAD cases (P=0.12-0.98). Overall CNV rates were not significantly different in TS cases with and without LSL.

Table III.

Distribution of Autosomal CNVs in TS Cases and Controls

| All | >200 Kb | rare events | rare genic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS | Controls | P | TS | Controls | P | TS | Controls | P | TS | Controls | P | |

| Total autosomal CNVs | 1282 | 56425 | 0.003 | 303 | 13419 | 0.004 | 419 | 17541 | 0.005 | 179 | 7528 | 0.4 |

| Deletions | 409 | 29247 | 0.0009 | 86 | 3398 | 0.03 | 143 | 9815 | 0.0003 | 47 | 4382 | 0.002 |

| Duplications | 873 | 27178 | 0.0002 | 217 | 10021 | 0.003 | 276 | 7726 | 0.0005 | 132 | 3146 | 1.0×10−6 |

TS: 418 Turner syndrome genotypes; ETAAD: 110 early onset TAAD genotypes; Controls: 15,414 genotypes from four dbGAP datasets; P: P-values for comparisons with controls. TS CNV rates (total length of CNVs per individual or average size of CNVs) were uniformly increased across all CNV categories vs controls and were comparable to ETAAD CNV rates. In contrast, TS CNV rates were not significantly different from ETAAD CNV rates across all CNV categories (P=0.12-0.98).

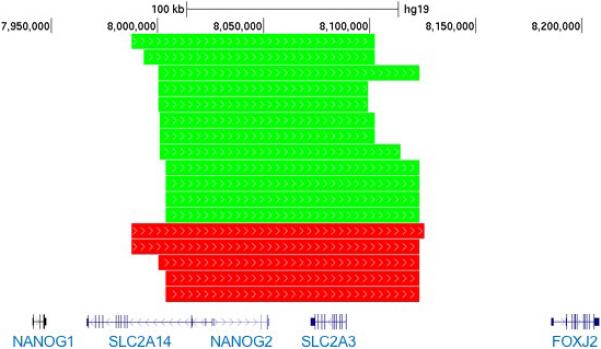

In case-control comparisons, we identified a copy number polymorphism (CNP) in 12p13.31 that is significantly associated with LSL in TS (OR 3.7, 95% CI 1.3-10.6, P=0.011, Figure 2). This well-defined CNP is 120,000 base pairs in length and contains three protein-coding genes (SLC2A3, SLC2A14, NANOGP1). The frequency of this CNP was 7.4% in TS cases with BAV (12/162), 2.1% in TS cases without BAV (5/233), 4.3% in TS cases overall (17/395) and 4.2% in dbGAP controls (398/9428). TS subjects with the 12p13.31 CNP were significantly more likely to have experienced an acute aortic dissection (2/20, 10%) than TS subjects without this CNP (6/394, 1.5%, chi-squared P=0.007). The body size-adjusted diameter of the ascending aorta was not significantly larger in CNP carriers (n=16, 21.2 mm/m2) than in TS subjects without the CNP (n=289, 19.0 mm/m2, P=0.057). LSL were significantly enriched among CNP carriers with 45,X karyotypes (11/12) in comparison with all other karyotypes (2/5, P=0.047). The prevalence of duplications involving this CNP was not significantly different in TS cases (20/21, 95%) and controls (322/398, 81% P=0.14).

Figure 2. 12p31.31 Copy Variant is Enriched in TS Subjects with LSL.

Locus plot of 12p13.31 illustrates enrichment of CNVs in TS cases with LSL (green) compared with TS cases without LSL (red). The scale in kilobases, hg19 genomic coordinates (7.9-8.2 Mb) and RefSeq gene structures are included to provide the genomic context.

The strength of the 12p13.31 CNP association with LSL in TS led us to consider that this CNV may also predispose to LSL in other clinical contexts. Therefore, we determined the frequency of the 12p13.31 CNP in two independent groups with BAV and TAAD. The 12p13.31 CNP was not significantly associated with sporadic BAV (n=480, P=0.71), sporadic TAAD (n=805, P=0.72), or in the combined analysis of both cohorts. Therefore, we conclude that common variation at 12p13.31 does not significantly contribute to non-syndromic BAV or TAAD.

Gene-based association tests also identified six recurrent rare CNVs in TS subjects with LSL (Table IV). These CNV regions were observed in subjects with LSL in the TS cohort and at least two other cohorts with BAV and TAAD, but were rare (frequency < 0.1%) in controls. Three of the six recurrent rare CNVs contain genes that cause cardiac and/or aortic defects when mutated in humans or animal models. Candidate genes in these regions are potential modifiers of LSL risk in TS and in sporadic BAV cases.

Table IV.

Recurrent Rare CNVs in TS Cases with Left-Sided Lesions

| Region | Type | Candidate Genes | Disease Gene | Animal Model | Prior CHD | Network | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7p15.2 | Del | HOXA3,HOXA4,HOXA5,HOXA6,HOXA7,EVX1,HOXA9,HOXA10,HOXA11,HOXA13,HOTTIP | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 21q21.1 | Dup*/Del | CXADR,BTG3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 13q12.11 | Dup* | ZMYM2,ZMYM5, GJA3,GJB6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 18p11.32 | Del | COLEC12,CETN1,CLUL1,C18ORF56,TYMS | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 1q43 | Dup*/Del | FH,KMO,WDR64,OPN3,CHML,PLD5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 4q32.3 | Dup*/Del | TRIM60,TRIM61,TMEM192 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Lists of candidate CNV regions ranked by prioritization scores. Region: in hg19 coordinates; Dup: duplication

disrupting duplication

Del: deletion; Disease Gene: mutations identified in subjects with congenital heart defects; Animal model: targeted disruption causes aortic and/or cardiac phenotypes; Prior CHD: CNVs discovered in subjects with congenital heart disease; Network: in top 10% of genes identified by ToppGene analysis using known BAV and TAAD genes as seeds.

DISCUSSION

Women with TS develop aortic dilation and dissection at rates up to 50 times greater than the general population [Carlson and Silberbach, 2009]. BAV and coarctation are similarly increased in TS and are strongly associated with aortic outcomes. In our cohort, ascending aortic dilation and acute aortic dissections were almost exclusively confined to TS women with BAV. Reduced dosage of sex chromosome genes is common to all TS women and is the most likely predisposing factor for LSL and TAAD in TS. However, monosomy X is not always sufficient to cause aortic disease by itself, because half of TS patients with 45,X karyotypes do not develop LSL. We hypothesize that a second event, such as an environmental factor or genetic lesion that disrupts cardiovascular development, interacts with monosomy X to cause LSL in TS. The results presented here provide the first evidence supporting that hypothesis by demonstrating that specific common and rare genetic variants affecting cardiac developmental genes are enriched in TS women with LSL.

We found that polymorphic duplications that include three genes in 12p13.31, SLC2A3, SLC2A14 and NANOGP1, are significantly associated with BAV, coarctation and aortic dissections in TS. Duplications of the same region are associated with septal and conotruncal heart defects in subjects with 22q11.2 deletions [Mlynarski et al., 2015]. Copy variants of this region were also found to be enriched in cohorts with rheumatoid arthritis and Huntington's disease [Veal et al., 2014; Vittori et al., 2014]. Functional studies implicated altered expression of the glucose transporter encoded by SLC2A3 (GLUT3) as a cause of cardiovascular, neuronal and immunological abnormalities in affected CNV carriers. SLC2A3 is expressed in the brain, pharyngeal arches and left ventricular outflow tract during development, and knockdown of the mouse and zebrafish orthologs causes early embryonic lethality [Ganguly et al., 2007; Carayannopoulos et al., 2014]. Mutation of SLC2A10, a paralog of SLC2A3, causes arterial tortuosity syndrome, a developmental disorder characterized by congenital malformations, aneurysms and dissections of the aorta and other arteries [Cheng et al., 2009]. The expression of SLC2A3 overlaps with SLC2A10 and may affect similar molecular pathways. As was reported for the 22q11 deletion cohort, we did not detect any significant enrichment of this CNP in non-syndromic BAV or TAAD cases, but we did observe that 45,X karyotypes are significantly enriched in TS CNP carriers with LSL. These observations support our hypothesis that TS women are sensitized to second genetic ‘hits’ that may contribute to the increased prevalence of LSL. Functional studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis, and to investigate the potential impact of this CNV on aortic development and aortopathy.

Women with TS develop several non-reproductive cancers at higher rates than the general population, and their peripheral blood leukocytes demonstrate elevated levels of autosomal aneuploidies and chromosomal instability [Hasle et al., 1996; Schoemaker et al., 2008; Ganmore et al., 2009]. Extensive somatic mosaicism of X chromosome structural variants, with tissue-specific variability, is also frequent in TS. We found that the genome-wide burden of genic CNVs is significantly increased in TS when compared with controls. These data suggest that a fundamental cellular defect of chromosomal maintenance and segregation may predispose to meiotic loss of one X chromosome and persist throughout life, contributing to disease-specific risks for malignancy and cardiovascular disease.

Bondy and her colleagues observed that LSL in TS are strongly associated with a single copy of Xp, based on data from rare subjects with Xp deletions [Bondy et al., 2013]. We confirmed this association, but found that increased copy number of Xq appears to attenuate the risk for LSL. In subjects with isochromosomes, who have a single copy of Xp but up to 3 copies of Xq depending on the abundance of mosaic cell lines, we observed a significant and dose-dependent decrease in the prevalence of LSL. Therefore, we propose that copy gains of genes that escape X inactivation in Xq may compensate for reduced dosage of Xp genes and protect against LSL. MECP2 and FLNA in Xq28 are candidate modifier genes for this effect. Both are dosage-sensitive genes that regulate cardiac development [Feng et al., 2006; Alvarez-Saavedra et al., 2010]. FLNA escapes X inactivation and causes LSL or TAAD when mutated [de Wit et al., 2011]. However, large interstitial deletions and duplications involving these genes are not associated with other features of Turner syndrome. Confirmation of this hypothesis is likely to require manipulation of gene dosage in cells or animal models.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the study participants and team members who contributed to these studies. Access to genotypes and clinical information from the LVOTO cohort was generously provided by John W. Belmont, M.D., Ph.D. and Neil Hanchard, M.D., Ph.D., of Baylor College of Medicine (supported by 1U54HD083092, 5R01HD039056, 5R01HL090506 and 5R01HL091771) and Kim McBride, M.D., of The Ohio State University and Nationwide Children's Hospital (supported by 5R01HL109758). The GenTAC Registry has been supported by US Federal Government contracts HHSN268200648199C and HHSN268201000048C from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (Bethesda, M.D.).

The datasets used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from the Genetic Architecture of Smoking and Smoking Cessation Study found at dbGaP accession phs000404.v1.p1, the NEI Refractive Error Collaboration (NEIREC) Database found at dbGaP accession phs000303.v1.p1, the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) found at dbGaP accession phs000428.v1.p1, and the Genetics of Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy (FECD) Study found at dbGaP accession phs000421.v1.p1. FECD was primarily supported by grants R01EY016514 (DUEC, PI: Gordon Klintworth), R01EY016482 (CWRU, PI: Sudha Iyengar) and 1X01HG006619-01 (PI: Sudha Iyengar, Natalie Afshari). The HRS genetic data was sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grants U01AG009740, RC2AG036495 and RC4AG039029) and was conducted by the University of Michigan. Funding support for NEIREC was provided by the National Eye Institute. Genotyping for the Genetic Architecture of Smoking and Smoking Cessation Study, which was performed at the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR), was funded by 1 X01HG005274-01. CIDR is fully funded through a federal contract from the National Institutes of Health to The Johns Hopkins University, contract number HHSN268200782096C. Assistance with genotype cleaning, as well as with general study coordination for the Genetic Architecture of Smoking and Smoking Cessation Study was provided by the Gene Environment Association Studies (GENEVA) Coordinating Center (U01 HG004446). Funding support for collection of the Genetic Architecture of Smoking and Smoking Cessation Study datasets and samples was provided by the Collaborative Genetic Study of Nicotine Dependence (COGEND; P01 CA089392) and the University of Wisconsin Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (P50 DA019706, P50 CA084724). We would like to thank the FECD participants, NEIREC participants and the NEIREC and FECD Research Groups for their valuable contribution to this research.

The authors are indebted to the International Bicuspid Aortic Valve Consortium (BAVCon) and the National Registry of Genetically Triggered Aneurysms and Cardiovascular Conditions (GenTAC) for providing samples and clinical data. A complete list of BAVCon and GenTAC investigators and their affiliations is available in the Supplementary Online Material. The GenTAC Registry Investigators are: William Ravekes, M.D., Harry C. Dietz, M.D., Ph.D., Kathryn W. Holmes, M.D., Jennifer Habashi, M.D., Dianna M. Milewicz, M.D. Ph.D., Siddharth K. Prakash, M.D., Ph.D, Scott A. LeMaire. M.D., Shaine A. Morris, M.D., M.P.H, Cheryl L Maslen, Ph.D., Howard K. Song, M.D., Ph.D, G. Michael Silberbach, M.D, Reed E. Pyeritz, M.D., Ph.D., Joseph E. Bavaria M.D., Karianna Milewski, M.D., Ph.D., Richard B. Devereux, M.D., Ph.D., Jonathan W. Weinsaft, M.D., Mary J. Roman, M.D., Ralph Shohet, M.D., Nazli McDonnell, M.D., Federico M. Asch, M.D., Kim A. Eagle, M.D., H. Eser Tolunay, Ph.D., Patrice Desvigne-Nickens, M.D., Hung Tseng, Ph.D. and Barbara L. Kroner, Ph.D. The BAVCon Investigators are: Simon C. Body, M.B.Ch.B., M.P.H., Eric M. Isselbacher, M.D., Kim A. Eagle, M.D., Bo Yang, M.D., Hector I. Michelena, M.D., Maurice Enriquez-Sarano, M.D., Giuseppe Limongelli, M.D., Ph.D., Maria Giovanna Russo, M.D., Ph.D., Mona Nemer, Ph.D., Malenka M. Bissell, M.D., B.M., MRCP.Ch, Eduardo Bossone, M.D., Ph.D., Rodolfo Citro, M.D., Ph.D., Alessandro Frigiola, M.D., Francesca Pluchinotta, M.D., Patrizio Lancelotti, M.D., Ph.D., Dan Gilon, M.D., Alessandro Della Corte, M.D., Ph.D., Gordon Huggins, M.D., Yohan Bossé, Ph.D., Patrick Mathieu, M.D., Philippe Pibarot, D.V.M., Ph.D, Rita K. Milewski, M.D., Ph.D., Joseph Bavaria, M.D., Dianna M. Milewicz, M.D., Ph.D., Siddharth Prakash, M.D., Ph.D., Arturo Evangelista, M.D., Jose Rodriguez-Palomares, M.D., Gisela Teixido Tura, M.D., Joshua C Denny, M.D., M.S., D. Woodrow Benson, M.D., Ph.D. and Victor Dayan, M.D., Ph.D.

REFERENCES

- Alvarez-Saavedra M, Carrasco L, Sura-Trueba S, Demarchi Aiello V, Walz K, Neto JX, Young JI. Elevated expression of MeCP2 in cardiac and skeletal tissues is detrimental for normal development. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2177–2190. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellott DW, Hughes JF, Skaletsky H, Brown LG, Pyntikova T, Cho TJ, Koutseva N, Zaghlul S, Graves T, Rock S, Kremitzki C, Fulton RS, Dugan S, Ding Y, Morton D, Khan Z, Lewis L, Buhay C, Wang Q, Watt J, Holder M, Lee S, Nazareth L, Alföldi J, Rozen S, Muzny DM, Warren WC, Gibbs RA, Wilson RK, Page DC. Mammalian Y chromosomes retain widely expressed dosage-sensitive regulators. Nature. 2014;508:494–499. doi: 10.1038/nature13206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondy CA. Care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: a guideline of the Turner Syndrome Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:10–25. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondy CA, Bakalov VK, Cheng C, Olivieri L, Rosing DR, Arai AE. Bicuspid aortic valve and aortic coarctation are linked to deletion of the X chromosome short arm in Turner syndrome. J Med Genet. 2013;50:662–665. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayannopoulos MO, Xiong F, Jensen P, Rios-Galdamez Y, Huang H, Lin S, Devaskar SU. GLUT3 gene expression is critical for embryonic growth, brain development and survival. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;111:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, Airhart N, Lopez L, Silberbach M. Moderate aortic enlargement and bicuspid aortic valve are associated with aortic dissection in Turner syndrome: report of the international turner syndrome aortic dissection registry. Circulation. 2012;126:2220–2226. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.088633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, Silberbach M. Dissection of the aorta in Turner syndrome: two cases and review of 85 cases in the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr0620091998. doi: 10.1136/bcr.06.2009.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Xu H, Aronow BJ, Jegga AG. Improved human disease candidate gene prioritization using mouse phenotype. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:392. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CH, Kikuchi T, Chen YH, Sabbagha NG, Lee YC, Pan HJ, Chang C, Chen YT. Mutations in the SLC2A10 gene cause arterial abnormalities in mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:381–388. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cripe L, Andelfinger G, Martin LJ, Shooner K, Benson DW. Bicuspid aortic valve is heritable. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit MC, de Coo IF, Lequin MH, Halley DJ, Roos-Hesselink JW, Mancini GM. Combined cardiological and neurological abnormalities due to filamin A gene mutation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s00392-010-0206-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Chen MH, Moskowitz IP, Mendonza AM, Vidali L, Nakamura F, Kwiatkowski DJ, Walsh CA. Filamin A (FLNA) is required for cell-cell contact in vascular development and cardiac morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19836–19841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609628104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly A, McKnight RA, Raychaudhuri S, Shin BC, Ma Z, Moley K, Devaskar SU. Glucose transporter isoform-3 mutations cause early pregnancy loss and fetal growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1241–55. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00344.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganmore I, Smooha G, Izraeli S. Constitutional aneuploidy and cancer predisposition. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R84–93. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasle H, Olsen JH, Nielsen J, Hansen J, Friedrich U, Tommerup N. Occurrence of cancer in women with Turner syndrome. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:1156–1159. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroner BL, Tolunay HE, Basson CT, Pyeritz RE, Holmes KW, Maslen CL, Milewicz DM, LeMaire SA, Hendershot T, Desvigne-Nickens P, Devereux RB, Dietz HC, Song HK, Ringer D, Mitchell M, Weinsaft JW, Ravekes W, Menashe V, Eagle KA. The National Registry of Genetically Triggered Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Cardiovascular Conditions (GenTAC): results from phase I and scientific opportunities in phase II. Am Heart J. 2011;162:627–632 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMaire SA, McDonald MN, Guo D, Russell L, Miller CC, Johnson RJ, Bekheirnia MR, Franco LM, Nguyen M, Pyeritz RE, Bavaria JE, Devereux R, Maslen C, Holmes KW, Eagle K, Body SC, Seidman C, Seidman JG, Isselbacher EM, Bray M, Coselli JS, Estrera AL, Safi HJ, Belmont JW, Leal SM, Milewicz DM. Genome-wide association studies identify a major susceptibility locus for thoracic aortic aneurysms and aortic dissections at 15q21.1, encompassing FBN1. Nat Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ng.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin MB, McBride KL, Pignatelli R, Fernbach S, Combes A, Menesses A, Lam W, Bezold LI, Kaplan N, Towbin JA, Belmont JW. Echocardiographic evaluation of asymptomatic parental and sibling cardiovascular anomalies associated with congenital left ventricular outflow tract lesions. Pediatrics. 2004;114:691–696. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0782-L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matura LA, Ho VB, Rosing DR, Bondy CA. Aortic dilatation and dissection in Turner syndrome. Circulation. 2007;116:1663–1670. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride KL, Zender GA, Fitzgerald-Butt SM, Koehler D, Menesses-Diaz A, Fernbach S, Lee K, Towbin JA, Leal S, Belmont JW. Linkage analysis of left ventricular outflow tract malformations (aortic valve stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome). Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:811–819. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlynarski EE, Sheridan MB, Xie M, Guo T, Racedo SE, McDonald-McGinn DM, Gai X, Chow EW, Vorstman J, Swillen A, Devriendt K, Breckpot J, Digilio MC, Marino B, Dallapiccola B, Philip N, Simon TJ, Roberts AE, Piotrowicz M, Bearden CE, Eliez S, Gothelf D, Coleman K, Kates WR, Devoto M, Zackai E, Heine-Suñer D, Shaikh TH, Bassett AS, Goldmuntz E, Morrow BE, Emanuel BS, International CC. Copy-Number Variation of the Glucose Transporter Gene SLC2A3 and Congenital Heart Defects in the 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96:753–764. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoe K, Endo A. Expression level of Rps4 mRNA in 39,X mice and 40,XX mice. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1994;67:52–54. doi: 10.1159/000133796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S, Guo D, Maslen CL, Silberbach M, Milewicz D, Bondy CA, GenTAC I Single-nucleotide polymorphism array genotyping is equivalent to metaphase cytogenetics for diagnosis of Turner syndrome. Genet Med. 2014;16:53–59. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash SK, LeMaire SA, Guo DC, Russell L, Regalado ES, Golabbakhsh H, Johnson RJ, Safi HJ, Estrera AL, Coselli JS, Bray MS, Leal SM, Milewicz DM, Belmont JW. Rare copy number variants disrupt genes regulating vascular smooth muscle cell adhesion and contractility in sporadic thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:743–756. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao E, Weiss B, Fukami M, Rump A, Niesler B, Mertz A, Muroya K, Binder G, Kirsch S, Winkelmann M, Nordsiek G, Heinrich U, Breuning MH, Ranke MB, Rosenthal A, Ogata T, Rappold GA. Pseudoautosomal deletions encompassing a novel homeobox gene cause growth failure in idiopathic short stature and Turner syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;16:54–63. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raychaudhuri S, Korn JM, McCarroll SA, Altshuler D, Sklar P, Purcell S, Daly MJ. Accurately assessing the risk of schizophrenia conferred by rare copy-number variation affecting genes with brain function. PLoS genetics. 2010;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer BM, Lewin MB, Stout KK, Gill E, Prueitt A, Byers PH, Otto CM. The bicuspid aortic valve: an integrated phenotypic classification of leaflet morphology and aortic root shape. Heart. 2008;94:1634–1638. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.132092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoemaker MJ, Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, Wright AF, Jacobs PA, UK CCG Cancer incidence in women with Turner syndrome in Great Britain: a national cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veal CD, Reekie KE, Lorentzen JC, Gregersen PK, Padyukov L, Brookes AJ. A 129-kb deletion on chromosome 12 confers substantial protection against rheumatoid arthritis, implicating the gene SLC2A3. Hum Mutat. 2014;35:248–256. doi: 10.1002/humu.22471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittori A, Breda C, Repici M, Orth M, Roos RA, Outeiro TF, Giorgini F, Hollox EJ, REGISTRY IOTEHDN Copy-number variation of the neuronal glucose transporter gene SLC2A3 and age of onset in Huntington's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:3129–3137. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hadley D, Liu R, Glessner J, Grant SF, Hakonarson H, Bucan M. PennCNV: an integrated hidden Markov model designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in whole-genome SNP genotyping data. Genome Res. 2007;17:1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.6861907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.