Abstract

Purpose

To quantify retinal capillary density and morphology in uveitis using SD-OCTA.

Design

Cross-sectional, observational study

Methods

Healthy and uveitic subjects were recruited from two tertiary care eye centers. Prototype SD-OCTA devices (Cirrus, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA) were used to generate 3×3 mm2 OCTA images centered on the fovea. Subjects were placed into 3 groups based on the type of optical microangiography (OMAG) algorithm used for image processing (intensity-and/or phase) and type of retinal segmentation (automatic or manual). A semi-automated method was used to calculate skeleton density (SD), vessel density (VD), fractal dimension (FD), and vessel diameter index (VDI). Retinal vasculature was assessed in the superficial retinal layer (SRL), deep retinal layer (DRL), and non-segmented retinal layer (NS-RL). A generalized estimating equations model was used to analyze associations between the OCTA measures and disease status within each retinal layer. A P value < 0.05 was accepted as significant. Reproducibility and repeatability were assessed using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC).

Results

The SD, VD, and FD of the parafoveal capillaries were lower in uveitic eyes compared to healthy eyes in all retinal segments. In addition, SD and VD were significantly lower in the DRL of subjects with uveitic macular edema. There was no correlation in any capillary parameters and anatomic classification of uveitis.

Conclusions

Quantitative analysis of parafoveal capillary density and morphology in uveitis demonstrates significantly lower capillary density and complexity. SD-OCTA algorithms are robust enough to detect these changes and can provide a novel diagnostic index of disease for uveitis subjects.

Introduction

Macular abnormalities are a common manifestation of uveitis regardless of anatomic location of disease.1-4 Inflammatory mediators play a key role in the disruption of the retinal microvasculature, leading to visually debilitating findings such as macular edema (ME), retinal ischemia, and neovascularization (NV).1-3 Fluorescein angiography (FA) and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) remain the most commonly used tools to detect these uveitic findings.4-7 However, standard FA requires an invasive procedure, does not reliably provide capillary-level resolution, and needs subjective assessment that does not correlate with OCT anatomic findings in many cases.8-10

Quantitative and objective analysis of macular involvement in uveitis has largely been limited to measuring retinal thickness with OCT11-13, or less commonly measuring retinal blood perfusion velocity using retinal function imager.14 Ultra-widefield FA has been used to identify areas of retinal ischemia, leakage, and retinal vasculitis that are not visible using conventional FA6 and to quantify some of these findings.15 While wide-field FA is an essential tool, quantitative studies are confounded by relatively low-resolution images, distortion of peripheral anatomy due to imaging artifacts, lid artifacts, and a limited time window for optimal imaging during the FA transit phase.15 In addition, wide-field images generally do not provide high-resolution images of the foveal capillaries where vision-threatening macular pathology most often occurs.

SD-OCT angiography (SD-OCTA) is a novel imaging modality that utilizes the advances in OCT technology to provide high-resolution angiographic information of the retinal microvasculature.8, 16, 17 SD-OCTA allows both qualitative and quantitative assessment of microvascular integrity in retinal vascular diseases, particularly in the parafovea where the most visually-significant pathology is often present (e.g. macular edema). We have demonstrated that qualitative SD-OCTA findings in the macula are reliable and correlate well with macular FA findings in diabetic retinopathy16 and retinal venous occlusion.17 In addition, macular capillary structural details by SD-OCTA are higher in resolution, and also provide quantitative measures of disease severity. Most importantly, SD-OCTA is a non-invasive method that can be repeated frequently, and provides near histology level resolution for assessment of capillary density.8

In this study, we use SD-OCTA to quantitatively assess the density and morphology of parafoveal retinal capillaries in subjects with a history of uveitis. In particular, we address three important clinical questions: Are there differences in macular capillary density or morphology (1) between uveitic eyes and healthy eyes, (2) between uveitic eyes with ME and those without ME, and (3) between uveitic eyes with different anatomic foci of disease activity. We use three different image-processing and retinal segmentation algorithms to validate the reliability of our findings.

Methods

Subject Recruitment

This cross-sectional, observational case series on healthy and uveitic adult eyes was conducted at the University of Southern California Roski Eye Institute (USCREI) and the University of Washington Eye Institute (UWEI) over 14 months (November 2014 to January 2016). The study was approved by the USC Health Sciences Campus and University of Washington Institutional Review Boards for prospective recruitment and imaging of subjects using OCTA with subsequent image analysis. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects for participation in the research. The study was conducted in accordance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations and adhered to the tenets stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Adult patients diagnosed with uveitis by fellowship trained uveitis specialists were recruited for this study. Because macular pathology can occur in any type of uveitis,1-4, 11, 12 all types of uveitis were eligible regardless of the known anatomic location, clinical diagnosis, or clinical features. In cases of bilateral uveitis, both eyes were eligible. In unilateral uveitis, only the uveitic eye was included in the analysis. Subjects who were unable to fixate or had significant media opacities were excluded. In addition, subjects with concomitant retinal vascular disease not associated with uveitis (e.g. diabetic retinopathy, retinal vascular occlusion, glaucoma, and age-related macular degeneration) were excluded. Healthy subjects with no ocular disease other than refractive error were recruited as controls.

Three cohorts of uveitis and healthy subjects were recruited for the study: 2 groups from USCREI and 1 group from UWEI. Each group was imaged with the same OCTA device model but under different processing and segmentation settings, as described in the imaging protocol below. All uveitis patients were evaluated according to standard-of-care with complete history, ocular exam, imaging, and appropriate laboratory studies and categorized by fellowship trained uveitis specialists using Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature criteria.5 Clinical and demographic information including age, gender, ocular exam findings and diagnosis, and pertinent medical history such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and autoimmune disease were collected. All patients were imaged on the same day as their clinical evaluation, and at least one 3×3 mm2 scan centered on the fovea was taken in each eye of interest for subsequent evaluation.

SD-OCTA Imaging Protocol

Prototype SD-OCTA devices (Cirrus, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA, USA) with a central wavelength of 840nm and scan speed of 68 kHz (68,000 A-scans per second) were used to generate en face OCTA images using optical microangiography (OMAG) algorithms that have been described.17-20 Two different OMAG image processing and/or segmentation schemes were used for the study as described below. Subjects were grouped as follows.

In group 1, subjects were imaged with an intensity-only OMAG algorithm.20 A semi-automated segmentation algorithm was used to generate three horizontal OCTA slabs: the superficial retinal layer (SRL; automatically calculated as 60% of the depth between the inner limiting membrane (ILM) and 110μm above the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)); the deep retinal layer (DRL; automatically calculated as the remaining 40% of the depth up to 110μm above the RPE); and the non-segmented retinal layer (NS-RL; automatically segmented from the ILM to RPE).

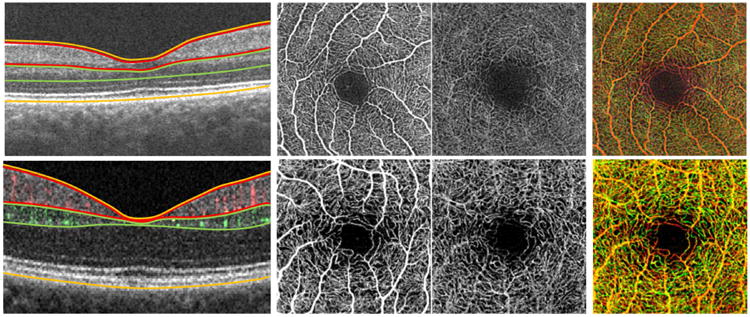

In group 2, a combined intensity and phase-based OMAG algorithm19 was used with the same semi-automated segmentation algorithm as group 1 (Figure 1, top row).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the semi-automated and manual optical coherence tomography angiography layer segmentation methods used in the study. (Top row) Semi-automated segmentation algorithm. (Top left to right) Optical coherence tomography (OCT) segmentation defined the superficial retinal layer (SRL; between red lines), deep retinal layer (DRL; between green lines), and non-segmented retinal layer (NS-RL; between orange lines) using borders of the retina as described in the methods. Gray-scale OCT angiographic (OCTA) slabs are then automatically generated containing the SRL, DRL, and NS-RL. (Top right) Depth-encoded OCTA image showing all retinal plexuses in one image, with the superficial vessels shown in red and deeper vessels shown in green. (Bottom row) Manual segmentation algorithm. (Bottom left to right) Manual segmentation of the OCT scan was performed to define the vascular plexuses in the SRL (superficial perfusion in red on OCT, bordered by red lines), the DRL (deeper perfusion in green on OCT, bordered by green lines), and the NS-RL (bordered by orange lines). This resulted in corresponding grayscale angiographic slabs for the SRL, DRL, and NS-RL following manual segmentation. (Bottom right) Depth-encoded angiographic slab showing the superficial (red) and deep (green) retinal plexuses.

In group 3, subjects were imaged with combined intensity and phase-based OMAG algorithm and manual segmentation. In the manual segmentation, the SRL extended from the ILM to the edge of the inner plexiform layer (IPL); the DRL extended from the inner nuclear layer (INL) to the edge of the outer plexiform layer (OPL); and the NS-RL extended from the ILM to the RPE (Figure 1, bottom row).

For each subject, at least one 3×3 mm2 scan centered on the fovea was taken in each eye of interest. Quality was assessed based on corresponding structural en face images and co-registered OCT B-scans to exclude artifacts, segmentation errors, or poor image focus. Images were graded on an A-F scale using signal intensity (reported from 0/10 for no signal detection to 10/10 for excellent signal detection by the OCTA device) as well as subjective user evaluation of the scans. All scans graded A-C (signal intensities greater than 7/10, no significant floaters or segmentation errors, and minimal motion artifact) were included. Scans graded D-F were excluded (images that had signal intensities of 6/10 or less, large or diffuse floaters, significant segmentation errors, or motion artifacts). This methodology was described in our previous studies.16,17

Quantitative Algorithm for SD-OCTA Images

A semi-automated algorithm with interactive user interface was used to quantify retinal vascular density and morphology. Vascular density was characterized by skeleton density (SD) and vessel density (VD), while vascular morphology was characterized by fractal dimension (FD) and vessel diameter index (VDI). All OCTA images were converted into 8-bit files (586 × 585 pixels; one pixel ≈ 5.13 × 5.13 microns2). The original grayscale image was then converted into a binarized black-and-white image using a three-way combined method consisting of a global threshold, hessian filter, and adaptive threshold in MATLAB (R2013b, MathWorks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts), as shown in Figure 2. The foveal avascular zone (FAZ) was used to determine the global threshold for each image. The resulting image was then processed separately by two mechanisms: (1) median adaptive threshold with top hat filter of 12 pixels, and (2) hessian filter only. The 2 generated images were then combined to form the final binarized image (Figure 2, fourth row). This binary image was used to calculate VD, which represented a unitless proportion of the total area of pixels with detected OCTA signal (white pixels in the binarized image) compared to the total area of pixels in the binarized image as follows:

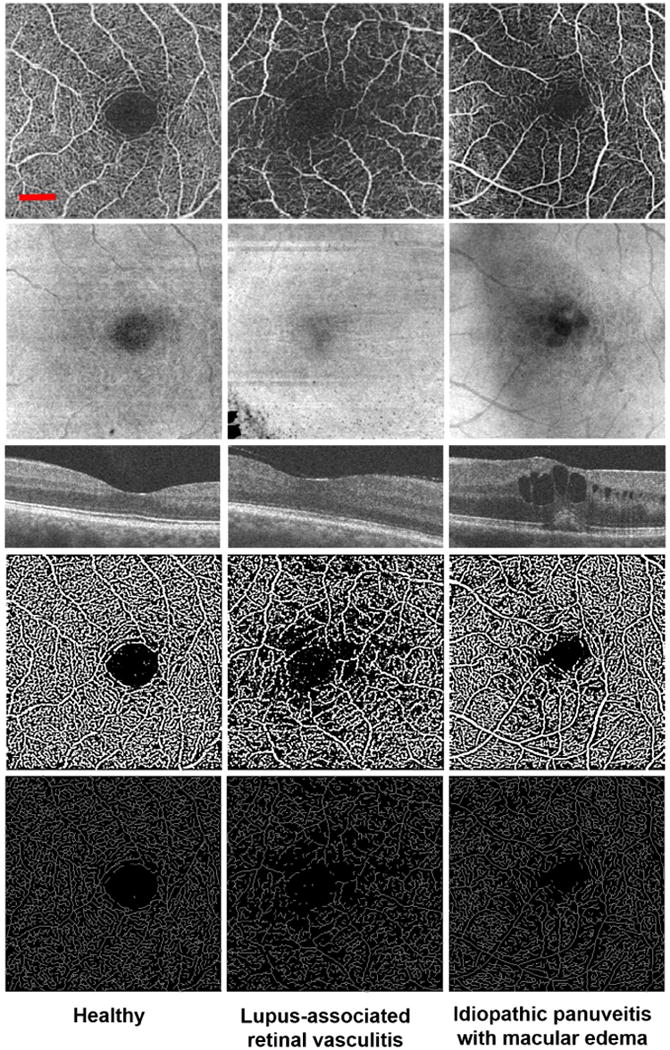

Figure 2.

Non-segmented optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) images of the parafoveal capillaries in healthy and uveitic eyes. Columns represent one eye each from 1 healthy and 2 uveitic subjects, as labeled at the bottom of each column. Rows represent the different types of images evaluated in the study for each eye, including (from top to bottom): original grayscale OCTA, structural en face, OCT B-scan, binarized image, and skeletonized image. (Left column) Representative eye from a healthy 34-year-old female subject. (Left column, top row) The grayscale OCTA image shows normal foveal capillary perfusion. (Left column, second row) The corresponding structural en face image showing no significant artifacts. (Left column, third row) Cross-sectional OCT B-scan showing no edema. (Left column, fourth and fifth rows) The binarized and skeletonized images are included for enhanced contrast of vasculature. (Middle column) Uveitic eye of a 63-year-old female patient with systemic lupus erythematosus complicated by retinal vasculitis. (Middle column, top row) The grayscale OCTA image shows lower density and branching complexity of the parafoveal vasculature. (Middle column, second row) The structural en face image shows some loss of OCT signal in the bottom left corner of the image that does not impact the interpretation of the image. (Middle column, third row) OCT B-scan showing no edema. (Middle column, fourth and fifth rows) Areas of impaired perfusion can be seen more clearly in the binarized and skeletonized images, respectively. (Right column) A 29-year-old female with idiopathic panuveitis. (Right column, top row) The grayscale OCTA image shows distinct areas of impaired retinal perfusion extending into the fovea. (Right column, second row) The structural en face image shows areas of dense, circumscribed hyporeflectivity in the fovea, as well as an overlying shadowing effect. (Right column, third row) Corresponding areas of circumscribed hyporeflectivity on OCT. (Right column, fourth and fifth rows) The binarized and skeletonized images show disruption of the foveal avascular zone in areas corresponding to edema. The red scale bar (top left) shows a length of 500 μm. This scale applies to all images in this figure except the OCT B-scan (middle row).

Where B(i, j) represents all the pixels arising from SD-OCTA signal decorrelation with detected blood perfusion (white pixels in the binarized image of Figure 2), and X(i, j) are all the pixels in the binarized image. The pixel coordinates are represented by (i, j) within the (N × N) pixel array of the binarized image. The summation notations for B(i, j) and X(i, j) are squared to represent the areas of the 2-dimensional image (both length and width).

The binarized image was used to create the skeletonized SD-OCTA image to measure statistical length of moving blood column, or SD (pixels / pixels2). This was done by repeatedly deleting the outer boundary of pixels in the binarized image until one pixel remained to represent that section of detected blood perfusion (Figure 2, bottom row). SD was calculated using this skeletonized image as follows:

Where L(i, j) represents pixels arising from linearized OCTA signal decorrelation (white pixels in the skeletonized image of Figure 2), and X(i, j) are all the pixels in the skeletonized image. The pixel coordinates (i,j) in this case refer to the pixels in the skeletonized OCTA image (assuming an image with N × N pixel array). Here, the summation notation for L(i, j) is not squared because this is a 1-dimensional measurement of only length within the skeletonized image. However, X(i, j) remains squared to account for the 2-dimensionality of the skeletonized image as a whole.

FD was then calculated using the box-counting method based on the skeletonized image, as described previously.18 FD was measured to determine the level of complexity exhibited by the capillary network around the fovea.

The VDI measured the average vessel diameter (pixels) in the OCTA image based on the binarized and skeletonized images as follows:

Where B(i, j) represents pixels arising from the binarized OCTA signal decorrelation (total number of 2-dimensional white pixels of the binarized image in Figure 2), and L(i, j) represents pixels occupied by the linearized OCTA signal decorrelation (total number of 1-dimensional white pixels of the skeletonized image in Figure 2).

Measurements of retinal capillary density and morphology were conducted on both segmented SD-OCTA images (SRL and DRL) and the NS-RL SD-OCTA images. The avascular retinal slab (outer nuclear layer to the external limiting membrane) was not analyzed because it does not contain any vessels.8

Statistical Analysis

Within each group, uveitic eyes were analyzed and compared to healthy eyes. In addition, uveitic eyes with macular edema (ME) were compared to uveitic eyes without ME to determine if ME was associated with any vascular changes. Finally, uveitic eyes were stratified based on location of disease (anterior, posterior, or panuveitis) to assess whether the strength of association between capillary changes and uveitis differs according to disease location. Intermediate uveitis was not included in this analysis given lack of data.

All quantitative measurements are reported with the mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence interval for each OCTA measure as calculated by a single investigator. A P < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant. SAS® (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses.

The generalized estimating equations (GEE) model adjusting for age, gender, and correlated data due to inclusion of both eyes was used to analyze associations between the OCTA measures and disease status within each retinal layer. Analyses in which data from all groups were combined to form a single healthy cohort and single uveitis cohort were also performed with the GEE model to adjust for multiple comparisons and group differences. Each OCTA measure was analyzed separately from the other measures to avoid inflation of parameter estimate standard errors due to colinearity. Due to concerns of small sample size, nonparametric analysis was performed to evaluate the statistical significance of comparisons. Parametric analyses were used to estimate β and confidence intervals.

Two graders independently analyzed all OCTA images. Reproducibility was based on the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) using non-segmented images. Each grader analyzed all non-segmented OCTA images twice to determine repeatability in each case using the ICC.

Results

Subject Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic data of all subjects included in the final study groups. Table 2 shows the different etiologies of uveitis based on anatomic classification in each study group. Out of a total of 106 healthy eyes and 130 uveitic eyes imaged, 94 (88%) healthy eyes and 61 (47%) uveitic eyes were ultimately included in the analysis. Eyes were excluded due to poor OCTA image quality (7 healthy eyes, or 6.6%; and 29 uveitic eyes, or 22.3%, due to visual acuity of 20/200 or worse and/or dense floaters). Additional eyes were excluded for having concomitant retinal vascular disease (5 healthy eyes, or 4.7%; and 31 uveitic eyes, or 23.8%) or uninvolved eyes in unilateral uveitis (10 eyes, or 7.7%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of healthy and uveitic subjects in three cohorts that were used for assessment of optical coherence tomography angiography based metrics.

| Subject Characteristics | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Healthy | Uveitis | Healthy | Uveitis | Healthy | Uveitis | |

| Number of Subjects (n) | 18 | 19 | 31 | 17 | 2 | 5 |

| Number of Eyes | 33 | 30 | 58 | 25 | 3 | 6 |

| Male : Female | 8 : 10 | 7 : 12 | 18 : 13 | 3 : 14 | 1 : 1 | 0 : 5 |

| Age (Mean ± SD), years | 34.8 ± 11.9 | 54.6 ± 12.9 | 37.9 ± 14.2 | 48 ± 15.7 | 63.6 ± 8.5 | 44.3 ± 18.4 |

| Age Range (years) | 24 – 63 | 26 – 72 | 22 – 68 | 21 – 72 | 55 – 72 | 26 – 71 |

| Diabetes Prevalence | 0 | 16% (n = 3) | 0 | 6% (n = 1) | 0 | 20% (n = 1) |

| HTN Prevalence | 0.11 (n = 2) | 32% (n = 6) | 0.06 (n = 2) | 24% (n = 4) | 0 | 20% (n = 1) |

| HLD Prevalence | 0.06 (n = 1) | 26% (n = 5) | 0.03 (n = 1) | 6% (n = 1) | 0 | 40% (n = 2) |

| ME Prevalence | - | 53% (16 eyes) | - | 36% (9 eyes) | - | 0 |

SD = standard deviation; HTN = hypertension; HLD = hyperlipidemia; ME = macular edema.

Table 2.

Summary of the spectrum of clinical diagnoses within each cohort that was used for validation of optical coherence tomography angiography based metrics.

| GROUP 1 | Total number of affected eyes (n) | Total number of eyes with ME (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior Uveitis | 6 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Herpetic iridocyclitis | 2 | 0 |

| Microscopic polyangitis with anterior uveitis | 2 | 0 |

| Idiopathic | 2 | 1 |

| Posterior Uveitis | 18 (12) | 10 (6) |

| Acute retinal necrosis | 1 | 1 |

| Autoimmune retinopathy | 2 | 2 |

| Birdshot chorioretinopathy | 2 | 0 |

| Lupus-associated | 1 | 0 |

| Multifocal chorioretinitis | 2 | 2 |

| PAI-1 mutation associated vasculitis | 1 | 0 |

| Punctate inner choroidopathy | 1 | 0 |

| Recurrent MEWDS | 2 | 2 |

| Retinitis pigmentosa-associated | 2 | 0 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis-associated | 1 | 1 |

| Tuberculosis chorioretinitis | 2 | 2 |

| Uveal lymphoid hyperplasia | 1 | 0 |

| Panuveitis | 6 (4) | 5 (4) |

| Idiopathic | 5 | 4 |

| Varicella zoster virus-associated panuveitis | 1 | 1 |

| Intermediate uveitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

| ||

| GROUP 2 | Total number of affected eyes | Total number of eyes with ME |

|

| ||

| Anterior Uveitis | 7 (5) | 1 (1) |

| Human leukocyte antigen B27 uveitis | 2 | 1 |

| Idiopathic | 3 | 0 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis-associated | 2 | 0 |

| Posterior Uveitis | 11 (8) | 5 (4) |

| Acute retinal necrosis | 1 | 1 |

| Birdshot chorioretinopathy | 3 | 1 |

| Lupus-associated | 4 | 2 |

| Microscopic polyangitis with retinal vasculitis | 1 | 1 |

| Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome | 2 | 0 |

| Panuveitis | 7 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Idiopathic | 7 | 3 |

| Intermediate uveitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

| ||

| GROUP 3 | Total number of affected eyes | Total number of eyes with ME |

|

| ||

| Anterior Uveitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Posterior Uveitis | 6 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Ampiginous chorioretinopathy | 2 | 0 |

| Idiopathic retinal vasculitis | 2 | 0 |

| Lupus retinal vasculitis | 1 | 0 |

| Recurrent MEWDS | 1 | 0 |

| Panuveitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Intermediate uveitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

ME = macular edema; PAI-1 = plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; MEWDS = multiple evanescent white dot syndrome.

Qualitative Analysis of OCTA Images

Figure 2 demonstrates representative NS-RL images of healthy and uveitic eyes in 2-dimensional (2D) grayscale, structural en face, OCT B-scan, binarized, and skeletonized forms. The microvasculature was qualitatively assessed for regions of impaired retinal perfusion and the general organization of vessels in each retinal layer.

In healthy eyes, the SRL demonstrated a continuous distribution of capillaries extending within the plane of the layer. The DRL had reticular and less-continuous pattern of vasculature consistent with the fact that capillaries in this segment are diving into-and-out of the plane of the image (Figure 1). These observations are consistent with previous OCTA, FA, and histological observations of these layers.8, 10 The DRL in OCTA images consisted of both the true decorrelation signal from blood flow within that layer as well as the projection artifacts from more superficial retinal layers.21, 22. In general, healthy eyes demonstrated an intact parafoveal capillary network (Figure 2, left column).

In contrast to healthy controls, uveitis subjects demonstrated distinct areas of qualitatively impaired retinal perfusion in the NS-RL both in the absence and presence of macular edema (Figure 2 middle and right columns, respectively). These changes were less prominent but also qualitatively apparent in the SRL and DRL in more severe cases (data not shown).

Quantitative Analysis of OCTA Images

Of the 30 uveitic eyes imaged in group 1, 29 were used for subsequent quantitative analysis. One eye with significant attenuation of parafoveal blood perfusion due to branch retinal vein occlusion was excluded from analysis. For the remaining groups, all eyes imaged were included in the subsequent quantitative analysis.

Healthy vs. Uveitis Analysis

The binarized and skeletonized OCTA images for healthy and uveitic eyes were analyzed to determine the SD, VD, FD, and VDI for each subject. Values from healthy and uveitic subjects were compared. Analysis is reported for the aggregate of all subjects imaged regardless of image segmentation method. In general, there were significant and consistent differences observed when all the data were treated as a single group and within each sub-group (Table 3; Supplemental Material at AJO.com). For the all-group combined analysis, there were significantly lower capillary density parameters (SD and VD) in each retinal layer (SRL and DRL) and in the whole retina (NS-RL) of uveitic eyes compared to healthy eyes (Table 3). Uveitic subjects also demonstrated significantly lower branching complexity (FD) in the SRL, DRL and NS-RL. The VDI did not demonstrate a significant difference in any layer. It should be noted that when subjects with concomitant diabetes (7 eyes, 5 subjects) were removed from the entire study cohort, significance of the association between uveitic and healthy eyes did not change (data not shown). Please refer to Table 3 for detailed results including β estimates and confidence intervals.

Table 3.

Quantitative analysis of healthy eyes and uveitic eyes for all groups combined.

| OCTA Layer | OCTA Variable | Healthy | Uveitis | β (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRL | SD* | 0.097 ± 0.008 | 0.089 ±0.014 | -0.008 (-0.011, -0.006) | < 0.001 |

| VD* | 0.426 ± 0.019 | 0.378 ± 0.041 | -0.034 (-0.043, -0.024) | < 0.001 | |

| FD* | 1.713 ± 0.017 | 1.698 ± 0.032 | -0.016 (-0.022, -0.011) | < 0.001 | |

| VDI | 4.401 ± 0.342 | 4.285 ± 0.440 | 0.022 (-0.031, 0.075) | 0.56 | |

|

| |||||

| DRL | SD* | 0.102 ± 0.007 | 0.101 ± 0.009 | -0.003 (-0.005, -0.001) | 0.004 |

| VD* | 0.425 ± 0.017 | 0.412 ± 0.029 | -0.004 (0.008, 0.001) | 0.007 | |

| FD | 1.723 ± 0.016 | 1.724 ± 0.022 | -0.003 (-0.007, 0.001) | 0.05 | |

| VDI | 4.174 ± 0.316 | 4.099 ± 0.428 | 0.060 (0.005, 0.114) | 0.19 | |

|

| |||||

| NS-RL | SD* | 0.102 ± 0.008 | 0.095 ± 0.016 | -0.008 (-0.011, -0.005) | < 0.001 |

| VD* | 0.432 ± 0.020 | 0.387 ± 0.043 | -0.032 (-0.045, -0.020) | < 0.001 | |

| FD* | 1.720 ± 0.016 | 1.707 ± 0.034 | -0.017 (-0.023, -0.010) | < 0.001 | |

| VDI | 4.231 ± 0.305 | 4.119 ± 0.426 | 0.021 (-0.019, 0.061) | 0.25 | |

OCTA = optical coherence tomography angiography; SRL = superficial retinal layer; DRL = deep retinal layer; NS-RL = non-segmented retinal layer; SD = skeleton density; VD = vessel density; FD = fractal dimension; VDI = vessel diameter index.

The mean and standard deviation are reported for each set of scans (healthy or uveitis) of all group data combined within each retinal layer (Supplemental Material at AJO.com). The beta (β) represents the change in OCTA measurement value per unit increase as one transitions from healthy eyes to uveitic eyes. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P values for each comparison are also shown for each row of paired comparisons. Parametric analyses were used to estimate β and confidence intervals. Due to concerns of small sample size, nonparametric analysis was performed to evaluate the statistical significance of comparisons. Asterisks indicate metrics with significant differences between healthy and uveitic eyes.

OCTA Parameters in Subjects with Macular Edema (ME)

To determine whether presence of macular edema (ME) is associated with alterations in capillary density or morphology, a quantitative analysis was performed on eyes with ME only within each group. Only groups 1 and 2 included eyes with ME, so only these two groups were investigated in this analysis. In group 1, 16 (53%) uveitic eyes had ME. In group 2, 9 (36%) uveitic eyes had ME. Data from both groups were combined for analysis, which revealed significantly lower SD and VD in the DRL of uveitic subjects with macular edema (Table 4). No significant differences were found in the NS-RL or SRL as summarized in Table 4 (Supplemental Material at AJO.com). Of note, 2 of the 25 eyes (8%) with ME and 5 of the 30 eyes (17%) without ME were from were from subjects with concomitant diabetes but no diabetic retinopathy. When these 7 eyes from diabetic subjects were removed from both sub-groups, SD was no longer significantly different in the DRL of subjects with ME compared to those without ME; however, VD continued to remain a significantly decreased parameter in the purely uveitic patients compared to healthy subjects (data not shown).

Table 4.

Quantitative analysis for eyes with and without macular edema in Groups 1 and 2 combined.

| OCTA Layer | Group No. & OCTA Variable | Eyes without Macular Edema | Eyes with Macular Edema | β (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRL | SD | 0.088 ± 0.007 | 0.083 ± 0.010 | -0.003 (-0.006, 0.001) | 0.39 |

| VD | 0.392 ± 0.034 | 0.367 ± 0.044 | -0.015 (-0.031, 0.002) | 0.12 | |

| FD | 1.695 ± 0.015 | 1.685 ± 0.025 | -0.006 (-0.015, 0.003) | 0.41 | |

| VDI | 4.462 ± 0.133 | 4.406 ± 0.112 | -0.044 (-0.103, 0.016) | 0.45 | |

|

| |||||

| DRL | SD* | 0.100 ± 0.005 | 0.099 ± 0.004 | -0.002 (-0.004, 0.001) | 0.032 |

| VD* | 0.424 ± 0.008 | 0.416 ± 0.011 | -0.008 (-0.013, -0.003) | < 0.001 | |

| FD | 1.719 ± 0.010 | 1.719 ± 0.009 | -0.002 (-0.006, 0.002) | 0.40 | |

| VDI | 4.263 ± 0.165 | 4.224 ± 0.104 | -0.015 (-0.083, 0.053) | 0.62 | |

|

| |||||

| NS-RL | SD | 0.091 ± 0.011 | 0.091 ± 0.009 | 0.0002 (-0.004, 0.005) | 0.79 |

| VD | 0.391 ± 0.048 | 0.384 ± 0.037 | -0.001 (-0.019, 0.017) | 0.68 | |

| FD | 1.698 ± 0.024 | 1.700 ± 0.019 | 0.002 (-0.008, 0.012) | 0.82 | |

| VDI | 4.285 ± 0.124 | 4.245 ± 0.102 | -0.020 (-0.075, 0.035) | 0.84 | |

OCTA = optical coherence tomography angiography; SRL = superficial retinal layer; DRL = deep retinal layer; NS-RL = non-segmented retinal layer; SD = skeleton density; VD = vessel density; FD = fractal dimension; VDI = vessel diameter index.

Results from both groups combined are shown, including 14 eyes with no ME (n = 12) and 16 eyes with ME (n = 11) from Group 1, and 16 eyes with no ME (n = 12) and 9 eyes with ME (n = 8) from Group 2 (Supplemental Material at AJO.com). The mean and standard deviation are reported for each set of scans in each retinal layer. The beta (β) represents the change in OCTA measurement value per unit increase as one transitions from uveitic eyes without macular edema (ME) to uveitic eyes with ME within that group (corresponding to each row). The 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P values for each comparison are also shown for each row. Parametric analyses were used to estimate β and confidence intervals. Due to concerns of small sample size, nonparametric analysis was performed to evaluate the statistical significance of comparisons. Asterisks indicate metrics with significant differences between uveitic eyes with and without ME from that group.

OCTA Parameters in Subjects with Different Anatomic Classification of Disease

Subjects with uveitis were subdivided based on classification of anterior, posterior or panuveitis for each group. Each uveitis subgroup was then compared to that group's healthy cohort. Overall results were similar across all subgroups, showing that there were no significant or consistent differences in any parameter based on anatomic classification of uveitis (Supplemental Material at AJO.com).

Reproducibility and Repeatability of Analyses

Two investigators independently measured the SD, VD, FD, and VDI of the non-segmented images of healthy and uveitic eyes using the semi-automated quantitative algorithm, each at two different time points. Repeatability of measurements by each observer was found to be very high (ICC> 0.99) for all four parameters. Comparison of results between the two investigators showed high reproducibility, with ICC values of ≥ 0.95 for the SD, VD, FD, and VDI measurements. Only one set of measurements from one grader was used for the final analysis.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that there are significant qualitative and quantitative changes in the parafoveal capillary density and morphology of subjects with uveitis that can be reliably detected using OCTA. The differences identified between healthy and uveitic eyes were consistent and significant whether they were identified by semi-automated (Groups 1 and 2) or manual (Group 3) segmentation methods to define retinal layer boundaries. Our results were also consistent and significant whether we used intensity only (Group 1) or intensity and phase (Groups 2 and 3) based OCT angiography, indicating that these findings are robust regardless of analysis method at least in these cohorts. Most importantly, our results were reproducible between two separate groups of uveitis patients recruited by fellowship trained uveitis experts from two different tertiary eye care centers. These findings strongly suggest that quantitative assessment of parafoveal capillary density and morphology are clinically important and measurable parameters for uveitis.

The underlying intraocular inflammation in uveitis, regardless of anatomic location, can lead to ME.4, 15, 23, 24 This is hypothesized to result from the release of inflammatory cytokines that disrupt the inner and outer blood-retinal-barrier in addition to other structural changes.3, 24, 25 These changes occur even in anterior uveitis, presumably due to diffusion of inflammatory mediators in the vitreous.3 The highly significant differences in capillary density and morphology that we detected in uveitic subjects shows that the effects of intraocular inflammation can be quantitatively measured even within a 3×3 mm2 parafoveal window. In addition to investigating gross changes in the peripheral retina with wide-field imaging studies, OCTA assessment of changes in the parafoveal capillary density and branching complexity may provide a unique assessment of disease severity that is not otherwise available.

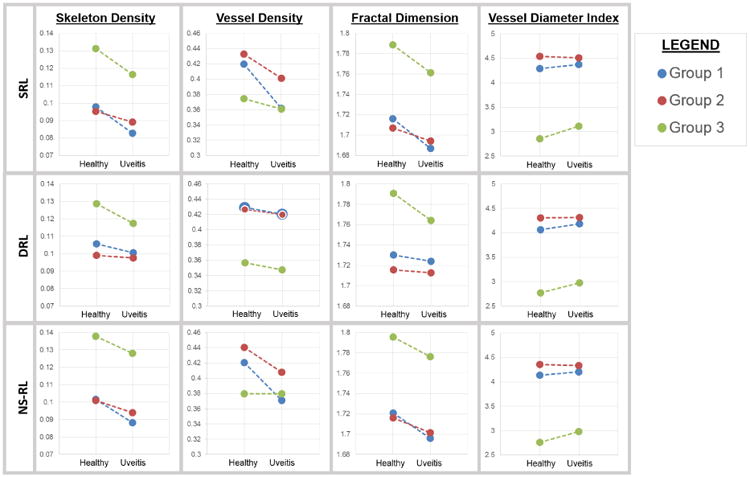

In our study, the SRL and NS-RL showed similarly-sloped magnitudes of change when comparing healthy to uveitic eyes, whereas the DRL demonstrated smaller magnitudes of change for all parameters, particularly in groups 1 and 2 (Figure 3). This smaller magnitude of change in the DRL may be attributed to the confounding effects of projection artifacts that would blunt our ability to visualize real but small changes at this level.22 We used a manual segmentation methodology to attempt to correct for projection artifacts by selecting only for perfusion within the appropriate layers of the retina and deriving the angiogram from this raw OCT B-scan flow data. While this correction method is not perfect, the larger magnitudes of change in the DRL of group 3 compared to groups 1 or 2 (Figure 3) suggest that DRL changes may be underestimated due to projection artifacts.

Figure 3.

Correlation of optical coherence tomography angiography based metrics with disease status (healthy vs. uveitic eyes). The mean values of measured skeleton density (SD), vessel density (VD), fractal dimension (FD), and vessel diameter index (VDI) are presented for each study group and retinal segmentation for healthy and uveitic eyes. In general, the superficial retinal layers (SRL) and non-segmented retinal layers (NS-RL) showed significantly lower SD, VD, and FD between healthy and uveitic eyes within all groups. The lines connecting the points in each group are there to emphasize the similarity in the magnitude and direction of the difference in each group. These were not paired groups. The deep retinal layer (DRL) showed significant differences in the SD, VD, and FD of group 1 and the SD, FD, and VDI of group 3. The DRL showed smaller magnitudes of change for each parameter when using a semi-automated segmentation algorithm as in groups 1 and 2, but not group 3 which was manually segmented.

Our investigation of uveitic ME showed significant changes in the DRL parameters despite any potential projection artifacts. These DRL changes correlate well with the physical location of intraretinal cystoid spaces in the inner retina (generally inner nuclear and plexiform layers). This finding reinforces the anatomic accuracy of the segmentation methods that we have used in this and previous studies.8, 16, 17 The co-localization of ME and DRL changes strongly suggest that the DRL findings are real and that the DRL is involved in some way in uveitic ME.

These findings must be interpreted with some measure of caution. First, it is not possible to attribute causality of these vascular changes to either macular edema or uveitis alone solely based on this cross-sectional study, since a longitudinal analysis following patients before, during, and after development of ME was not performed using OCTA. The lower DRL parameters may represent an actual change in the density of viable and patent capillaries due to ME. However, it is also possible that the lower DRL parameters simply represent displacement of retinal capillaries by the ME (mechanical displacement), or are due to attenuation of the DRL signal by the ME in that layer. Any one or all of these mechanisms may play a role in explaining the DRL findings. Future studies should be aimed at carefully examining these possibilities in larger cohorts. Secondly, the findings of significant change in the DRL may be confounded by the coexistence of diabetes in some of the patients (7 eyes; 5 subjects). However, when removing these eyes from the analysis, we found that the results of healthy versus uveitis patients remained the same for each measure (results not shown). In addition, the edema subgroup analysis remained mostly the same, still showing a significant change in the VD in purely uveitic patients (results not shown). However, significance of the SD was lost with removal of diabetic subjects. Thus, it is possible that there is some effect of diabetes that could only be observed through quantitative analysis of OCTA images, as demonstrated in the study by Kim et al (in press).26 Nevertheless, the sustained presence of significant change in the deep parafoveal microvasculature of purely uveitic patients without diabetes in the form of vessel density changes shows that uveitis may still be an important factor to consider in the setting of edema.

Our study has several limitations. First, our study involves cross-sectional analysis of a relatively small cohort of a heterogeneous set of uveitis cases (Table 2). Thus, it was not possible to pursue a statistically sound etiology-based analysis of capillary parameters in the scope of this study. This would certainly be an important question to investigate in future studies with defined and sufficiently sized subgroups of uveitis cases. Nevertheless, our overall quantitative findings of healthy versus uveitic eyes remained consistent, showing the clinical applicability and robustness of our quantitative algorithms and providing a foundation for future studies using these methods. In addition, the study was powered at > 90% for most of the OCTA measures (97.4%, 95.4%, and 93.6% for SD, VD, and FD, respectively) for the detection of differences between healthy and uveitic eyes within the non-segmented layer. VDI was powered at 77.2%. Second, all image analysis was conducted using a 3×3 mm2 window around the fovea, so results may not be generalizable to a larger or different area of the retina. Our findings support the histologic and FA findings of uveitis-associated retinal vascular changes in the macula and offer a foundation for future qualitative and quantitative studies on uveitic eyes using OCTA. Future studies using larger field-of-view on OCTA would be useful to investigate peripheral changes which have previously been documented with FA but without the level of capillary detail that OCTA provides.6, 15 Finally, we report findings using both automated and manual segmentation algorithms, both of which have inherent limitations which continue to be the subject of intense research for improvement. Improvements to the current semi-automated and manual segmentation algorithms would be important to investigate any real changes in the deeper retinal layers, which at this time is prone to projection artifacts and segmentation errors.21, 22 Nevertheless, this study shows that there is overall consistency of analyses (for both the uveitis and healthy groups) across the different segmentation algorithms (Supplemental Material at AJO.com). This serves as an indicator that results from prior studies with different pathologies and segmentation methods may continue to be reliable regardless of the type of algorithm used.

Despite these limitations, our study establishes an important and novel application of OCTA for the evaluation of parafoveal microvasculature in uveitis. Our results show significantly lower density and complexity of capillary perfusion and strongly suggest that OCTA evaluation of uveitis may be useful in assessing disease severity or even disease activity if used prospectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support

This study was supported by grants from Research To Prevent Blindness (New York, NY) and the National Eye Institute (Bethesda, MD, #R01EY024158).

Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc. (Dublin, CA) provided the optical coherence tomography angiography system used in this study.

none

Footnotes

Supplemental Material available at AJO.com

- Amir H. Kashani is a consultant and recipient from Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc. (Dublin, CA).

- Ruikang K. Wang is a consultant, recipient, and patent holder from Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc. (Dublin, CA).

- Alice Y. Kim, Damien C. Rodger, Anoush Shahidzadeh, Zhongdi Chu, Nicole Koulisis, Narsing A. Rao, Carmen A. Puliafito, and Kathryn L. Pepple used the optical coherence tomography angiography devices provided by Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc. (Dublin, CA) for this study, and report no other proprietary/financial interest.

- Bruce Burkemper and Xuejuan Jian have no financial disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Liu T, Bi H, Wang X, Gao Y, Wang G, Ma W. Macular abnormalities in Chinese patients with uveitis. Optom Vis Sci. 2015;92(8):858–862. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durrani OM, Tehrani NN, Marr JE, Moradi P, Stavrou P, Murray PI. Degree, duration, and causes of visual loss in uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(9):1159–1162. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.037226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman G, Matos K, Pavesio CE. Cystoid macular oedema in uveitis: an unsolved problem. Eye (Lond) 2001;15(Pt 1):12–17. doi: 10.1038/eye.2001.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antcliff RJ, Stanford MR, Chauhan DS, et al. Comparison between optical coherence tomography and fundus fluorescein angiography for the detection of cystoid macular edema in patients with uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(3):593–599. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working G. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(3):509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong BK, Nazari Khanamiri H, Rao NA. Role of ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography in the management of uveitis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48(6):489–493. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nazari H, Dustin L, Heussen FM, Sadda S, Rao NA. Morphometric spectral-domain optical coherence tomography features of epiretinal membrane correlate with visual acuity in patients with uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(1):78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.01.032. e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsunaga D, Yi J, Puliafito CA, Kashani AH. OCT angiography in healthy human subjects. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2014;45(6):510–515. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20141118-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spaide RF, Klancnik JM, Jr, Cooney MJ. Retinal vascular layers imaged by fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography angiography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(1):45–50. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendis KR, Balaratnasingam C, Yu P, et al. Correlation of histologic and clinical images to determine the diagnostic value of fluorescein angiography for studying retinal capillary detail. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(11):5864–5869. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran TH, de Smet MD, Bodaghi B, Fardeau C, Cassoux N, Lehoang P. Uveitic macular oedema: correlation between optical coherence tomography patterns with visual acuity and fluorescein angiography. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(7):922–927. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.136846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markomichelakis NN, Halkiadakis I, Pantelia E, et al. Patterns of macular edema in patients with uveitis: qualitative and quantitative assessment using optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(5):946–953. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hee MR, Puliafito CA, Wong C, et al. Quantitative assessment of macular edema with optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113(8):1019–1029. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100080071031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng X, Kedhar S, Bhoomibunchoo C. Retinal blood flow velocity in patients with active uveitis using the retinal function imager. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126(10):1944–1947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karampelas M, Sim DA, Chu C, et al. Quantitative analysis of peripheral vasculitis, ischemia, and vascular leakage in uveitis using ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(6):1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.02.009. e1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsunaga DR, Yi JJ, De Koo LO, Ameri H, Puliafito CA, Kashani AH. Optical coherence tomography angiography of diabetic retinopathy in human subjects. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46(8):796–805. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20150909-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashani AH, Lee SY, Moshfeghi A, Durbin MK, Puliafito CA. Optical coherence tomography angiography of retinal venous occlusion. Retina. 2015;35(11):2323–2331. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reif R, Qin J, An L, Zhi Z, Dziennis S, Wang R. Quantifying optical microangiography images obtained from a spectral domain optical coherence tomography system. Int J Biomed Imaging. 2012 Jun;2012:509783. doi: 10.1155/2012/509783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang RK, An L, Francis P, Wilson DJ. Depth-resolved imaging of capillary networks in retina and choroid using ultrahigh sensitive optical microangiography. Opt Lett. 2010;35(9):1467–1469. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.001467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Y, Zhang Q, Thorell MR, et al. Swept-source OCT angiography of the retinal vasculature using intensity differentiation-based optical microangiography algorithms. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2014;45(5):382–389. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20140909-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia Y, Tan O, Tokayer J, et al. Split-spectrum amplitude-decorrelation angiography with optical coherence tomography. Opt Express. 2012;20(4):4710–4725. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.004710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang A, Zhang Q, Wang RK. Minimizing projection artifacts for accurate presentation of choroidal neovascularization in OCT micro-angiography. Biomed Opt Express. 2015;6(10):4130–4143. doi: 10.1364/BOE.6.004130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham EM, Stanford MR, Shilling JS, Sanders MD. Neovascularisation associated with posterior uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71(11):826–833. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.11.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howes EL, Jr, Cruse VK. The structural basis of altered vascular permeability following intraocular inflammation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96(9):1668–1676. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910060294024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rotsos TG, Moschos MM. Cystoid macular edema. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2(4):919–930. doi: 10.2147/opth.s4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim AY, Chu Z, Shahidzadeh A, Wang RK, Puliafito CA, Kashani AH. Quantifying microvascular density and morphology in diabetic retinopathy using spectral domain optical coherence tomography angiography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016 Oct;57(9):362–370. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.