Abstract

Background

Pediatric blunt cerebrovascular injury (BCVI) lacks accepted treatment algorithms, and post-injury outcomes are ill defined.

Objective

To compare treatment practices among pediatric trauma centers and describe outcomes for available treatment modalities.

Methods

Clinical and radiographic data were collected from a patient cohort with BCVI between 2003 and 2013 at 4 academic pediatric trauma centers.

Results

Among 645 pediatric patients evaluated with computed tomography angiography (CTA) for BCVI, 57 vascular injuries (82% carotid artery; 18% vertebral artery) were diagnosed in 52 patients. Grade I (58%) and II (23%) injuries accounted for most lesions. Severe intracranial or intra-abdominal hemorrhage precluded antithrombotic therapy (ATT) in 10 patients. Among the remaining patients, primary therapy was an antiplatelet agent in 14 (33%), anticoagulation in 8 (19%), endovascular intervention in 3 (7%), open surgery in 1 (2%), and no treatment in 16 (38%). Among 27 eligible grade I injuries, 16 (59%) were not treated, and choice to not treat varied significantly among centers (P < .001). There were no complications from medical management. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) <8 and increasing injury grade were predictors of injury progression (P = .001 and .004, respectively). Poor GCS (P = .023), increasing injury grade (P = .032), and concomitant intracranial injury (P = .024) correlated with increased risk of mortality. Treatment modality did not correlate with progression of vascular injury or mortality.

Conclusion

Treatment of BCVI with antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy is safe and may confer modest benefit. Nonmodifiable factors, including presenting GCS, vascular injury grade, and additional intracranial injury, remain the most important predictors of poor outcome.

Keywords: blunt, cerebrovascular, injury, pediatric

Blunt cerebrovascular injury (BCVI) from trauma to the carotid or vertebral artery can inflict a wide range of neurological sequelae.1-4 At the time of injury, vascular damage can result in cerebral infarction and permanent neurologic morbidity. Additionally, delayed ischemia may result from distal embolic events remote from the time of primary injury. Addressing these dangers is of principal concern for trauma and cerebrovascular specialists caring for these patients. Treatment algorithms exist for blunt cerebrovascular injury in adults,5 but because of a low incidence, such parameters are lacking in the pediatric literature. We present the largest series of pediatric BCVI to date. By correlating outcomes with the available treatment modalities, we outline several observations that can be applied to pediatric patients diagnosed with BCVI.

METHODS

Study Design

This study is a retrospective review of a patient cohort from the University of Utah/Primary Children's Hospital (PCH); Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt (MCJCHV) in Nashville, Tennessee; St. Louis Children's Hospital (STLCH) in St. Louis, Missouri; and Texas Children's Hospital (TCH) in Houston, Texas. Institutional review board and privacy board approval was obtained at each participating center prior to data collection.

Patient Population

The study population included all children (<18 years old) who underwent computed tomography angiography (CTA) evaluation of the head or neck for suspected traumatic BCVI at the 4 pediatric trauma centers during the 11-year study period (January 1, 2003 to December 31, 2013). The decision to obtain a CTA was at the discretion of the treating trauma and/or cerebrovascular team.

Data Collection

Trauma and radiology databases were queried to identify trauma patients that were screened for BCVI with CTA of the head or neck. Demographic information collected included treatment center, patient age, sex, and race.

Mechanism of injury, initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), focal neurological deficits, and mode of treatment for traumatic brain injury (TBI) (medical vs surgical) were collected. Radiological factors recorded included the presence of petrous temporal bone fracture, fracture through the carotid canal, and fracture involving the foramen transversarium. The presence of concomitant intracranial injury (epidural, subdural, or subarachnoid hemorrhage) and hypodensity on head CT consistent with stroke were recorded. Discharge disposition was dichotomized as home vs other.

The primary variable of interest, BCVI, was defined by the presence of internal carotid or vertebral artery injury and grade of injury diagnosed by CTA. Each injury was classified according to the BCVI scale.6 Grade I injury is characterized by intimal irregularity with <25% narrowing, Grade II injury is a dissection or presence of intramural hematoma with >25% narrowing, Grade III injury is the presence of a pseudoaneurysm, Grade IV injury is an occlusion, and Grade V injury is transection with extravasation. Radiographic progression was defined as worsening of the vascular injury (either by grade or severity) on follow-up neurovascular imaging.

The initial treatments included antiplatelet therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel), anticoagulation (heparin, low-molecular weight heparin, warfarin), endovascular treatment (coil embolization, stenting), open surgery, or no treatment. In some analyses, antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy were collectively defined as antithrombotic therapy (ATT).

Statistical Analysis

Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools.7 Data analysis was carried out in a de-identified manner at the lead site by the primary and senior authors, using SPSS® software version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

All data were summarized using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and counts and frequencies for categorical variables. Descriptive data was reported as mean (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) as deemed most appropriate, with relative proportions as percentages. Nominal data were compared via chi-squared or via Fisher's exact test, as dictated by case frequencies. Limited endpoint frequencies precluded performing multivariable logistic regression without over-fitting a predictive model. Thus, the correlation between individual, unadjusted covariates and outcome measures are presented.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Six hundred forty-five pediatric patients (mean age 8.6 ± 4.4 years, 63% male) were evaluated for BCVI with CTA of the head or neck at the 4 centers during the 11-year study period. Fifty-seven vascular injuries were diagnosed in 52 patients (Table 1), yielding an 8.1% incidence of BCVI. Sixty-nine percent of the patients were diagnosed at a single trauma center. Motor vehicle accidents (MVA) and high-energy force from projectiles or blunt objects were the most common mechanisms (35% each), followed by pedestrian injuries (17%) and falls (14%). The median GCS upon initial emergency department evaluation was 8 (IQR: 5-12). Eighteen patients (35%) presented with focal neurologic examination findings, and 14 (27%) had radiographic cerebral ischemia. Concomitant intracranial pathology was present in 35 patients (67%): 8 (15%) with epidural hematoma, 13 (25%) with subdural hematoma, 14 (27%) with subarachnoid hemorrhage, and 18 (35%) with cerebral contusions (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient and injury characteristics

| Patient Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Cohort size | 52 (100) |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 8.6 (5.4) |

| Male | 34 (65) |

| Center | |

| A | 6 (12) |

| B | 4 (8) |

| C | 6 (12) |

| D | 36 (69) |

| Injury mechanism | |

| Motor vehicle accident | 18 (35) |

| Pedestrian | 9 (17) |

| Fall, high energy | 1 (2) |

| Fall, low energy | 6 (12) |

| Projectile/object, low energy | 18 (35) |

| GCS | |

| ≤7 | 26 (50) |

| 8-12 | 11 (21) |

| 13-15 | 15 (29) |

| Focal neurologic exam | 18 (35) |

| Radiographic stroke at presentation | 14 (27) |

| Intracranial injury | 35 (67) |

| Epidural hematoma | 8 (15) |

| Subdural hematoma | 13 (25) |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 14 (27) |

| Contusion | 18 (35) |

| Artery | |

| IC carotid | 36 (69) |

| EC carotid | 12 (23) |

| IC vertebral | 3 (6) |

| EC vertebral | 6 (12) |

| Injury grade | |

| I | 30 (58) |

| II | 12 (23) |

| III | 5 (10) |

| IV | 2 (4) |

| V | 1 (2) |

| Temporal bone fracture | 12 (23) |

| Squamosal | 5 (42) |

| Petrous | 7 (58) |

| Fracture through carotid canal | 17 (33) |

| Cervical spine injury | 7 (14) |

| Fracture | 4 (57) |

| Ligamentous injury | 3 (43) |

| Fracture through transverse foramen | 2 (29) |

SD, standard deviation; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; IC, intracranial; EC, extracranial

Vascular Injuries

Among the 57 vascular injuries identified in 52 children, the intracranial carotid artery was the most common (69%) location, followed by the extracranial carotid artery (23%), the extracranial vertebral artery (12%), and the intracranial vertebral artery (6%) (Table 1). Fifty-eight percent were grade I lesions, 23% were grade II, and 10% were grade III. Grade IV and V injuries (4% and 2%) were less common. Temporal bone fractures and fractures through the carotid canal were present in 23% and 33% of patients, respectively. Fourteen patients (39%) with intracranial carotid artery injury had a bony fracture involving the carotid canal. Two patients had a fracture involving the cervical transverse foramen, and both were found to have extracranial vertebral artery injury. The mechanism of injury did not correlate with the vessel injured (P = .56) or the grade of injury (P = .820). Additionally, there was no difference among centers in grade of vascular injury identified (P = .146).

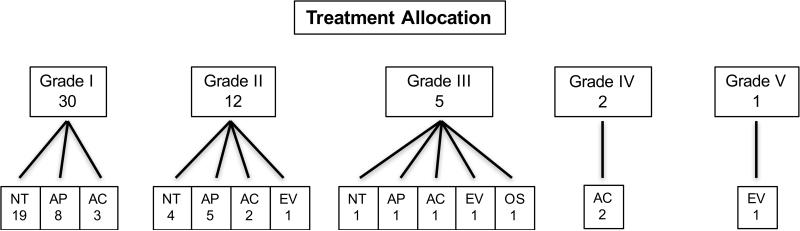

Treatment Patterns

Of the 52 children with BCVI, 26 (50%) were treated with ATT or endovascular or open surgery (Figure 1). Half of all patients with BCVI in this study (26) received no form of ATT. Ten patients (19%) had a contraindication (severe intracranial or intra-abdominal hemorrhage) to ATT, while treatment was deemed not necessary in 15 (29%). Antiplatelet medication was administered as the primary treatment modality in 14 (27%) patients (aspirin: 13; clopidogrel: 1), while 8 (15%) patients were placed on anticoagulation therapy (combination heparin or enoxaparin bridge to warfarin) (Table 2). The median duration of all antithrombotic treatment was 180 days (mean 131 days), and the median/mean duration of antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy was 120/107 days and 180/155 days, respectively. There were no hemorrhagic complications from medical management of cerebrovascular injury (Table 2). There were treatment differences by center as patients without hemorrhagic contraindications treated at one center were significantly less likely to receive ATT (43%) than those treated at any of the other 3 centers (100%) (P < .001). All untreated patients without contraindications harbored a grade I lesion. Regardless of treating center, all 8 patients with grade II injuries and without a contraindication were treated with ATT, and one also received endovascular therapy (Table 3). Endovascular and open surgery were primarily reserved for higher-grade lesions and were performed infrequently (3 and 1 patients, respectively). Analyzed ordinally, grade of vascular injury correlated with treatment modality, with patients with lower-grade lesions more frequently receiving antiplatelets or observation alone, compared with anticoagulation or surgical intervention (P = .022).

Figure 1.

Treatment flow diagram.

AC: anticoagulation; AP: antiplatelet; EV: endovascular; NT: no treatment; OS: open surgery

TABLE 2.

Treatments and outcomes of 52 patients with BCVI

| Treatment | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Primary treatment | |

| Antiplatelet | 14 (27) |

| Anticoagulation | 8 (15) |

| Endovascular | 3 (6) |

| Open surgery | 1 (2) |

| None | 26 (50) |

| Reason for no treatment | n=26 |

| Contraindicated | 10 (38) |

| Not indicated/death | 15 (58) |

| Contraindications | n=10 |

| IC hemorrhage | 9 (90) |

| Other organ trauma | 1 (10) |

| Duration of medical treatment, days (median/mean) | 180/131 |

| Complication from medical treatment | 0 (0) |

| Outcomea | n (%) |

| Discharge disposition | |

| Home | 28 (54) |

| Rehab facility | 18 (35) |

| Death | 6 (12) |

| Follow-up imaging obtained | 31/46 (67) |

| CTA | 16 (52) |

| MRA | 11 (35) |

| Angiogram | 4 (13) |

| Imaging results | |

| Healing/improved | 16 (52) |

| No change | 8 (26) |

| Progression | 6 (19) |

| Median follow-up, mo (95% CI) | 22.0 (10.0-36.0) |

| Delayed adverse events | 2 (4) |

| New/expanded stroke | 2 (4) |

| Delayed death | 0 (0) |

BCVI, blunt cerebrovascular injury; IC, intracranial; CI, confidence interval; CTA, computed tomography angiography; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography.

Percentage of follow-up imaging obtained based on the 46 patients who survived their initial hospital stay.

TABLE 3.

Primary treatment by injury grade

| Grade of Vascular Injury | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | |

| None | 19 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Antiplatelet | 8 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Anticoagulant | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Endovascular | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Open surgery | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Grading scale from Biffle et al.6: I – luminal irregularity or dissection with < 25% luminal narrowing; II – dissection or intramural hematoma with ≥ 25% luminal narrowing, intramural thrombus, or raised intimal flap; III – pseudoaneurysm; IV – occlusion; V – transection with free extravasation

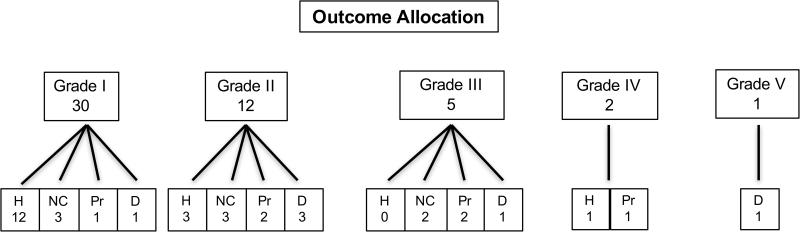

Outcomes

Among the 46 patients discharged from the hospital, 31 (67%) underwent follow-up imaging surveillance (Figure 2). The primary follow-up imaging modality was CTA (52%), followed by magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) (35%) and catheter angiography (13%) (Table 2). The median follow-up time of last surveillance image was 22.0 months. The majority of vascular injuries demonstrated luminal healing or improvement (52%) or no change (26%), while there was injury progression in 6 patients (19%) (at a median of 15.5 days). Among the 6 patients with radiographic progression, delayed stroke was observed in 2 during outpatient follow-up, and 1 died in-house prior to receiving any subsequent therapy directed toward the vascular injury. Two of these 6 patients who were receiving ATT (1, aspirin; 1, enoxaparin) had evidence of mild progression on surveillance imaging at 3 months, when their therapy was initially intended to be discontinued. Given these results, however, treatment was continued for an additional 3 months, after which repeat imaging demonstrated radiographic improvement. Two other patients were initially on anticoagulation therapy (1, warfarin; 1, enoxaparin) at the time that follow-up imaging demonstrated vessel injury progression. Both were transitioned to dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel), and subsequent imaging established improvement in vessel appearance. The final patient underwent vessel sacrifice via endovascular coil embolization, after repeat imaging demonstrated significant worsening of a prior grade 2 injury. The only characteristic that was associated with radiographic progression was a presenting GCS <8 (OR = 2.0, P = .001) (Table 4), although when analyzed in an ordinal fashion, increasing injury grade correlated with greater risk of radiographic injury progression (P = .004). The type of treatment modality prescribed did not influence the appearance of vessel disease on follow-up imaging (P = .446) (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Outcome flow diagram.

D: death; H: healing; NC: no change; Pr: progression

*Healing/No change/Progression represents the radiographic appearance at the time of the first follow-up imaging after primary/original treatment regimen had been installed.

TABLE 4.

Unadjusted odds ratio for radiographic progression of vascular injury, 95% confidence interval, and p values for 52 patients with BCVI

| Covariates | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Treating center | - | .582 |

| Mechanism of injury | - | .683 |

| Presenting GCS <8 | 2.0 (1.2-3.4) | .001 |

| Injury grade II-V | 8.3 (0.8-83) | .072 |

| Concomitant intracranial injury | 0.95 (0.2-5.2) | .642 |

| Treatment modality | - | .446 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; BCVI, blunt cerebrovascular injury

Six patients (12%) died during the index admission, whereas 28 (54%) were discharged to home and 18 (35%) went to a rehabilitation facility (Table 2). The presenting GCS was <7 in all of the patients who died, and all patients had at least one concomitant structural brain injury for which an external ventricular drain was placed or a craniotomy was performed. In no case was the cause of death deemed directly related to the cerebrovascular injury itself. Poor GCS (P = .001), injury grade >1 (P = .032), and concomitant intracranial injury (P = .024) all portended a greater mortality risk (Table 5). Neither injury mechanism (P = .220) nor treatment prescribed (P = .523) was associated with increased mortality after BCVI.

TABLE 5.

Unadjusted odds ratio for mortality, 95% confidence interval, and p values for 52 patients with BCVI

| Covariates | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Treating center | - | .647 |

| Mechanism of injury | - | .220 |

| Presenting GCS <8 | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | .023 |

| Injury grade II-V | 9.7 (1.1-90.4) | .032 |

| Concomitant intracranial injury | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | .024 |

| Treatment modality | - | .523 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; BCVI, blunt cerebrovascular injury

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report the largest cohort of pediatric BCVI from 4 institutions, focusing on management and outcomes. Among 645 pediatric patients evaluated with CTA for BCVI, 8.1% had vascular injury, the majority of which were grade I injuries and involved the intracranial carotid artery. Among patients without a treatment contraindication who survived, 72% received treatment in the form of ATT or surgical intervention—a practice that varied significantly by treating center. While our study was underpowered to determine whether treatment was protective for delayed stroke, no complications were identified after antiplatelet or anticoagulant administration. Poor presenting GCS, higher injury grade, and concomitant intracranial hemorrhage carried a poorer prognosis.

Cerebrovascular injury after blunt trauma is relatively uncommon in this population, occurring in 0.3%-0.9% of children suffering blunt trauma.4,8,9 Previously, the largest series of pediatric BCVI included 45 patients, with 69% of cases involving the carotid artery and 64% harboring low-grade (I-II) injuries8. In our series, the carotid artery was involved in 92% of patients, and 81% were low-grade injuries. An extra-axial hemorrhage (subdural or epidural hematoma) was identified in an alarming 40% of patients, although some were considered by the treating neurosurgeon not significant enough to warrant ATT contraindicated. Furthermore, half of all patients presented in a comatose state, a figure that far exceeds that for general pediatric trauma, which may indicate the relatively high energy needed to induce vascular injury from a blunt mechanism.

Early identification and treatment of these lesions has been advocated to minimize the risk of thromboembolic disease and/or vessel occlusion.5,8,10 In the adult literature, guidelines directing the diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of BCVI5 support the use of ATT for grade I and II lesions, whereas grade III lesions and patients with early neurologic deficits should be considered for operative intervention (level II evidence). Short-term angiographic follow-up for grade I-III injuries is recommended, but there is no consensus regarding the duration of follow-up or, for that matter, the duration of treatment.5

In the absence of equivalent evidence for children, pediatric practitioners are left to extrapolate these recommendations to their own patients. While definitive guidelines cannot be created from a 52-patient cohort, our goal is to describe several salient features of pediatric BCVI and offer 3 important observations: (1) there is little uniformity in the management of pediatric BCVI, and the sample size required to determine definitively whether the type of ATT administered has any influence on outcome would be very large; (2) the risks associated with ATT are low; and (3) nonmodifiable factors have the greatest influence on outcome.

Nonuniformity of Treatment Modality

Our report illustrates the heterogeneity in the treatment of BCVI. In one of the centers (at which the majority of patients were treated), only 43% of patients received ATT, whereas 100% of patients treated at the other 3 had ATT. Variability in treatment at the first center was in part a result of the perception that neurologically intact patients with a grade I injury may have been experiencing vessel spasm rather than true luminal injury. Thus, while the vessel injury was designated by the radiologist, the decision to treat remained in the hands of a multidisciplinary cerebrovascular team.11 This conservative approach is not without precedent: a 2011 survey of more than 780 cerebrovascular specialists found nearly 80% of respondents elected against treatment of asymptomatic vascular injuries.12 While this is in stark contrast to the 2010 trauma guidelines, it illustrates a true lack of consensus on the matter.5 Even within centers, there were discrepancies regarding the use of an antiplatelet or an anticoagulant agent as the primary treatment for lesions of the same grade. While it is impossible to extract from a retrospective dataset, it is likely that the decision to pursue endovascular or open surgical intervention for a given lesion was influenced by surgeon preference, thus introducing strong selection bias. Accordingly, drawing conclusions regarding outcomes following a given treatment is limited, and our predictive analysis therefore focused on factors free of bias.

While the type of ATT administered in this study did not influence the incidence of post-admission stroke, other series have suggested that non-treatment increases the risk of thromboembolic events. Kopelman et al9 reported a stroke rate of 38% (3/8) in children who received no ATT compared with 0% in those who were treated. Azarakhsh et al4 also observed a stroke rate of 0% in patients treated with ATT but 26% in patients who went untreated. Importantly, however, all but 1 patient who experienced stroke had at least a grade II lesion, and the majority of patients (86%) with a grade I injury neither received ATT nor suffered a stroke. In our series, 12 patients with grade I lesions received no ATT, and none suffered a delayed stroke or demonstrated worsening on follow-up imaging. Delayed strokes were, however, observed in 2 patients: one on aspirin for a grade I injury and the other on warfarin for a grade III injury.

A recently published randomized study focused on the efficacy of antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs at preventing stroke and death in 250 adults with nontraumatic symptomatic carotid and vertebral artery dissection found no difference between treatment modalities, but stroke was rare in both groups.13 Stroke or transient ischemic attack occurred in 2% of those treated with antiplatelet agents and 1% of those treated with anticoagulants. The authors concluded that any definitive study would require a very large sample, and their power calculations showed that the required total sample size using the endpoint of stroke, death, or major bleeding was almost 10,000 participants.

Minimal Risk of Antithrombotic Therapy

While the true efficacy of ATT is unknown and likely depends on numerous variables, our data suggest it is safe for use in children with BCVI. Among 22 patients treated primarily with ATT and others who received ATT after endovascular intervention, there were no hemorrhagic complications or systemic toxicities. Similarly, among 3 larger pediatric series totaling 79 patients,4,8,9 only a single hemorrhagic complication was reported. Gastric bleeding in this patient with preexisting gastric ulcer disease resolved after discontinuation of heparin.8 No complications were reported in the setting of antiplatelet administration. Similarly, in the adult literature, hemorrhagic complications are rare and typically resolve after medication discontinuation. Two studies involving 173 patients documented 3 bleeding complications from heparin, 1 from enoxaparin, and 1 from aspirin (gastrointestinal bleeding in the setting of gastric ulcers).3,14 Regarding the choice of anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy for BCVI, a greater efficacy of one over the other has not been demonstrated to date. Others have advocated for treatment initially with anticoagulation, supplementing with antiplatelet therapy only if patients develop thromboembolic symptoms.15 However, our data, and that which has been reviewed from the literature, do not suggest the superiority of anticoagulation, and antiplatelet therapy demonstrates a relatively more favorable side effect profile.

Disproportionate Influence of Nonmodifiable Factors on Outcome

In the setting of sparse and disparate data to guide pediatric BCVI, we attempted to identify factors that correlated with outcome. The 2 most reliable endpoints obtainable were vessel appearance on follow-up radiography and mortality. Unfortunately, functional outcomes were not available given the retrospective design. Nonetheless, we observed that progressively higher grades of vascular injury correlated with a greater risk of disease progression over time. Similarly, patients with a poor presenting GCS were twice as likely to experience disease worsening. Consistent with previous studies, we demonstrated a relationship between poor presenting GCS and mortality.16 Injury grades between II and V and concomitant intracranial injury were also associated with greater risk of in-hospital death. Importantly, neither the treating center nor the type of treatment prescribed, however, was correlated with the rate of mortality or with improvement—or worsening—of vessel characteristics on follow-up radiography.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of this study restrict the broad generalizability and reproducibility of our conclusions. This was a retrospective study in which data gathered from electronic charts was often many years old, and evaluating the effect of injury severity or treatment modality on common functional outcome scales such as the Glasgow Outcome Scale–Extended Pediatric Revision17 was not possible. The field would stand to benefit from such an analysis, which is currently absent in the literature.

Across all centers, treatments were allocated on a case-by-case basis incorporating factors ranging from mechanism of injury and presenting symptoms to injury severity and the presence or absence of cerebral infarction. Wide treatment variability existed between and within treatment centers, and conclusions about the efficacy of ATT for a given vascular injury cannot be made without acknowledging the influence of sampling and treatment bias present. Additionally, patients were not selected to undergo CTA in a systematic way; thus, selection bias is also a consideration. This bias is reflected in part by the relative disparity of BCVI cases across the 4 centers. Furthermore, since CTA diagnosis was among the inclusion criteria, a patient diagnosed with BCVI via MRA could have been left out of this cohort, resulting in underrepresentation of BCVI occurrence. While these represent relative limitations, they also emphasize the need for additional studies to help guide clinical practice.

Our conclusions would benefit from prospective adoption and implementation of a specific imaging and treatment protocol. The incidence of this injury, however, is extremely low, and the sample size, resources necessary, and costs would likely challenge the feasibility of such a study.

Practice Recommendations

In patients with low-grade injuries and without a contraindication, aspirin represents an appropriate balance between prevention of delayed embolic ischemia and minimizing adverse bleeding events. There is insufficient data to advocate a specific treatment regimen for grade II-V lesions. Rather, treatment should be based on clinical judgment after consideration of several clinical parameters including vessel characteristics, presence/absence of stroke on presentation, and concomitant intracranial hemorrhage. Our data suggests that a minority of pediatric BCVI warrants catheter angiography, for vessel characterization or treatment.

The optimal duration of therapy remains unclear, though 3 months of ATT is reasonable, with consideration given for longer treatment if follow-up imaging demonstrates radiographic progression or persistence of a concerning lesion.

Our data provides little evidence to support a specific follow-up protocol. Nonetheless, it is the authors’ opinion that repeat imaging is reasonable at 3 months post-injury or at the time of planned treatment discontinuation, or sooner if symptoms recur. If imaging suggests progression of vascular disease, our general practice is to continue surveillance imaging until the lesion stabilizes radiographically, with or without adjustment of current ATT regimen.

It should be noted that the above recommendations are made with the aforementioned limitations in mind, and that acceptance of a universal treatment algorithm for pediatric BCVI is unlikely until a larger study can confirm the clinical validity of these recommendations.

CONCLUSION

Independent of treatment, the incidence of delayed stroke or injury progression in grade I pediatric BCVI is low. Treatment of BCVI with antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy is safe and may confer a modest benefit. Nonmodifiable factors, including presenting GCS, grade of vascular injury, and presence of additional intracranial injury remain the most important predictors of a poor outcome.

Acknowledgment

We thank Kristin Kraus, MSc, for her editorial assistance.

Funding for this project was received through the Primary Children's Hospital Foundation Grant in the amount of $14,750. REDcap use and management was funded by the Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences grant support (8UL1TR000105 [formerly UL1RR025764] NCATS/NIH). There exist no personal or institutional financial interests held by any authors related to the content of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Corneille MG, Gallup TM, Villa C, et al. Pediatric vascular injuries: acute management and early outcomes. J Trauma. 2011;70(4):823–828. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820d0db6. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31820d0db6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biffl WL, Ray CE, Moore EE, et al. Treatment-related outcomes from blunt cerebrovascular injuries: importance of routine follow-up arteriography. Ann Surg. 2002;235(5):699–706. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200205000-00012. discussion 706-7. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1372521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller PR, Fabian TC, Bee TK, et al. Blunt cerebrovascular injuries: diagnosis and treatment. J Trauma. 2001;51(2):279–85. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200108000-00009. discussion 285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azarakhsh N, Grimes S, Notrica DM, et al. Blunt cerebrovascular injury in children: underreported or underrecognized?: A multicenter ATOMAC study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(6):1006–11. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31829d3526. discussion 1011-2. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31829d3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bromberg WJ, Collier BC, Diebel LN, et al. Blunt cerebrovascular injury practice management guidelines: the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 2010;68(2):471–477. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181cb43da. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181cb43da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biffl WL, Moore EE, Offner PJ, Brega KE, Franciose RJ, Burch JM. Blunt carotid arterial injuries: implications of a new grading scale. J Trauma. 1999;47(5):845–853. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199911000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones TS, Burlew CC, Kornblith LZ, et al. Blunt cerebrovascular injuries in the child. Am J Surg. 2012;204(1):7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.07.015. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kopelman TR, Berardoni NE, O'Neill PJ, et al. Risk factors for blunt cerebrovascular injury in children: do they mimic those seen in adults? J Trauma. 2011;71(3):559–64. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318226eadd. discussion 564. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318226eadd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabian TC, Patton JH, Croce MA, Minard G, Kudsk KA, Pritchard FE. Blunt carotid injury. Importance of early diagnosis and anticoagulant therapy. Ann Surg. 1996;223(5):513–22. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199605000-00007. discussion 522-5. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1372521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravindra VM, Riva-Cambrin J, Sivakumar W, Metzger RR, Bollo RJ. Risk factors for traumatic blunt cerebrovascular injury diagnosed by computed tomography angiography in the pediatric population: a retrospective cohort study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;15(6):599–606. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.PEDS14397. doi:10.3171/2014.11.PEDS14397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrigan MR, Weinberg JA, Peaks Y-S, et al. Management of blunt extracranial traumatic cerebrovascular injury: a multidisciplinary survey of current practice. World J Emerg Surg. 2011;6(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-6-11. doi:10.1186/1749-7922-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CADISS trial investigators. Markus HS, Hayter E, et al. Antiplatelet treatment compared with anticoagulation treatment for cervical artery dissection (CADISS): a randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(4):361–367. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70018-9. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards NM, Fabian TC, Claridge JA, Timmons SD, Fischer PE, Croce MA. Antithrombotic therapy and endovascular stents are effective treatment for blunt carotid injuries: results from longterm followup. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(5):1007–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.041. discussion 1014-5. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chamoun RB, Jea A. Traumatic Intracranial and Extracranial Vascular Injuries in Children. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2010;21(3):529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2010.03.009. doi:10.1016/j.nec.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein DM, Boswell S, Sliker CW, Lui FY, Scalea TM. Blunt cerebrovascular injuries: does treatment always matter? J Trauma. 2009;66(1):132–43. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318142d146. discussion 143-4. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318142d146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beers SR, Wisniewski SR, Garcia-Filion P, et al. Validity of a pediatric version of the Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(6):1126–1139. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2272. doi:10.1089/neu.2011.2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]