Abstract

Background

Epicardial adipose tissue (EAdT) is metabolically active and likely contributes to atrial fibrillation (AF) through the release of inflammatory cytokines into the myocardium or through its rich innervation with ganglionated plexi at the pulmonary vein ostia. The electrophysiological mechanisms underlying the association between EAdT and AF remain unclear.

Objective

Our study investigated the association of EAdT with adjacent myocardial substrate.

Methods

We studied 30 consecutive patients who underwent cardiac computed tomography as well as electro-anatomical mapping in sinus rhythm prior to an initial AF ablation procedure. Semiautomatic segmentation of atrial EAdT was performed and registered anatomically to the voltage map.

Results

In multivariable regression analysis clustered by patient, age (−0.01 per year) and EAdT (−0.29) were associated with log bipolar voltage as well as low-voltage zones (<0.5 mV). Age (OR=1.02 per year), male gender (OR=3.50), diabetes (OR=2.91), hypertension (OR=2.55), and EAdT (OR=8.56) were associated with fractionated electrograms and age (OR=2.80), male gender (OR=3.00), and EAdT (OR=7.03) were associated with widened signals. Age (OR=1.03 per year) and BMI (OR=1.06 per kg/m2) were associated with atrial fat.

Conclusion

The presence of overlaying EAdT was associated with lower bipolar voltage and electrogram fractionation as electrophysiologic substrates for AF. EAdT was not a statistical mediator of the association between clinical variables and AF substrate. BMI was directly associated with the presence of EAdT in patients with AF.

Keywords: Arrhythmias, Atrial fibrillation, Epicardial Adipose Tissue, Computerized Tomography, Fibrosis, Bipolar Voltage, Signal Fractionation

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary vein (PV) isolation is the cornerstone of AF ablation procedures.1 This reflects the importance of PV triggers in the initiation of AF. Factors which are important in maintenance of AF include heterogeneous fibrosis, refractory periods, and conduction velocity.2,3 Epicardial adipose tissue (EAdT), located between the myocardium and the visceral layer of the pericardium, has also been associated with AF.4 EAdT is metabolically active and may promote arrhythmogenesis through the release of inflammatory cytokines as well as adipokines into adjacent myocardium.4,5 Additionally, EAdT is postulated to contribute to AF through its rich innervation with ganglionated plexi in the proximity of the PV ostia.6 Despite recent advances, the electrophysiological mechanisms underlying the association between EAdT and AF remain unclear. Specifically, the association of EAdT with adjacent atrial myocardial substrate has not been studied. In the present study, we sought to a) determine clinical predictors of myocardial substrates namely low-voltage zones defined as <0.5 mV,7 as well as fractionated or widened electrograms, and b) examine EAdT as a potential mediator of the association between clinical factors such as obesity with myocardial substrates.

METHODS

PATIENTS

We performed a prospective cohort study of a subset of 30 consecutive patients from the ongoing Johns Hopkins Prospective AF Registry. Patients who underwent an initial radiofrequency ablation procedure for paroxysmal or persistent AF at Johns Hopkins Hospital from January to December 2014, and agreed to be included in the registry, were screened. We selected patients who underwent a pre-procedural computed tomography (CT) study but only included patients who were in sinus rhythm at the time of the voltage mapping (n=30). All patients provided written informed consent and this study was approved The Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board (JHM IRB).

MULTISLICE COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

Images were acquired using a commercially available 320-detector CT scanner (Aquilion ONE, Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan) up to one week before the procedure. Slice collimation was 320 × 0.5 mm, and tube voltage was 80, 100, or 120 kV, depending on the body habitus. Tube amperage ranged from 320 to 580 mA, dependent on body habitus and heart rate. Image acquisition was gated to 40% of the R-R interval during a breath-hold. Beta-blockers were used as needed to decrease the heart rate below 80 beats/min. The contrast protocol includes a total volume of 60 mL (70 mL if body mass index >30 kg/m2) of the nonionic low-osmolar iodinated contrast material iopamidol (Isovue 370, Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ) administered at a rate of 5–6 mL/s. First pass images were used for segmentation and analysis.

IMAGE ANALYSIS

CT images were processed offline using CartoSeg (Biosense Webster Inc, Diamond Bar, CA). Semiautomatic segmentation of the LA and pulmonary veins was performed. Total intra-thoracic adipose tissue was identified from the bifurcation of the pulmonary artery to the diaphragm as voxel intensities between −250 and −30 Hounsfield Units.8 Thereafter, EAdT was manually segmented by excluding portions of the intra-thoracic fat located outside the pericardium. We considered EAdT as a binomial variable derived from its presence or absence within 3 pixels (0.625 × 3 = 1.875 mm) of each endocardial mapping point. Left atrial volume was measured using Osirix (Pixmeo, Geneva, Switzerland) by manually contouring the LA.

ELECTROANATOMIC MAPPING

Prior to ablation, voltage mapping was performed during sinus rhythm using an electro-anatomic mapping (EAM) system (CARTO3, Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA) and a mapping catheter with a 3.5-mm distal tip and 2-mm inter-electrode spacing (NaviStar, ThermoCool or Thermocool Smarttouch, Biosense Webster Inc, Diamond Bar, CA). Endocardial contact during point acquisition was validated by recording of a stable contact signal for >2 beats. No immediate postoperative complications were noted.

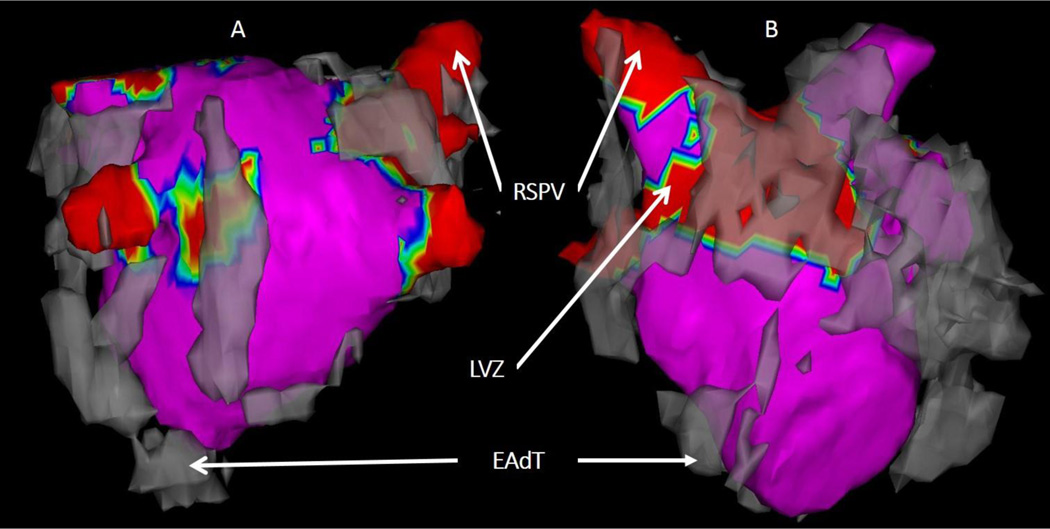

REGISTRATION OF EAdT AND VOLTAGE MAPS

Using CARTOMerge module, registration of the EAM and LA mesh was performed using 3–5 anatomic landmarks defined during the procedure followed by surface registration as seen in Figure 1. Each mapping point’s three-dimensional position coordinates and local electrograms were extracted, and the presence or absence of overlaying EAdT was noted for each site. EAM points recorded during ectopic beats- displaying differing intra-cardiac activation sequences or P wave morphologies on surface electrocardiograms from those of sinus rhythm were excluded.

FIGURE 1.

The EAdT mesh is shown in grey, registered to the low-voltage zones map (in red) as seen posteriorly (A) and anteriorly (B). (EAdT = epicardial adipose tissue, RSPV = right superior pulmonary vein, LVZ= low-voltage zone).

SIGNAL FRACTIONATION AND WIDENING

As previously described by Saghy et al9, sinus rhythm fractionation measurements were done manually for each electrogram. We counted the number of deflections crossing the baseline for each signal and measured its duration. In order to define the threshold for signal fractionation, we determined the 95th percentile of electrogram deflections in our patients and found that 95% of bipolar electrograms showed <6 deflections; therefore, electrograms with ≥6 deflections were defined as abnormally fragmented. We defined the threshold for signal widening in a similar manner and found that 95% of our electrograms had a duration <93 ms; therefore, electrograms with a duration ≥93ms were defined as abnormally widened.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical data as numbers or percentages. Due to non-normal (right skewed) distribution of bipolar voltage measures, log transformation was performed to enable analysis in a linear framework. The association of log bipolar voltage as the dependent variable with clinical variables as well as EAdT as independent variables was examined using multi-level multivariable generalized estimating equations (GEE) linear regression models, clustered by patient. An identity link function was used, with an exchangeable working correlation structure. The GEE model approach utilized here recognizes the existence of within-subject data clustering via modeling within-subject correlations. Failure to account for data clustering and the between-patient variability in slopes and intercepts can result in incorrect inferences and overstatement of statistical significance. A logit link-function was then used to look for non-linear associations between the same independent variables and dichotomized low voltage zones defined by voltage threshold <0.5 mV. Non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare bipolar voltage between low-voltage zones with and without EAdT as well as normal-voltage zones (≥0.5 mV) with and without EAdT. Subsequently, the association of EAdT as the dependent variable with clinical variables as independent variables was examined using multi-level multivariable GEE logistic regression models, clustered by patient (link function logit, exchangeable working correlation structure). Statistical analyses were performed using STATA (version 12, StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

Thirty patients (16 (53%) males, 58.9 ± 2.2 years, 22 (73%) paroxysmal, 8 (27%) persistent AF) were enrolled in this study. The mean CHA2DS2-VASc score was 1.7 ± 0.2 [median 2, interquartile range (IQR): 1–3], mean body mass index (BMI) was 28.7 ± 1.0 kg/m2 and mean left atrial volume was 112.1 ± 31.0 cm3. The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics in the study cohort (n=30)

| Clinical Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age, in years | 58.77 ± 2.19 |

| Male Gender | 16 (53%) |

| BMI, in kg/m2 | 28.72 ± 0.99 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 1.73 ± 0.24 |

| AF Duration, in years | 5.24 ± 1.09 |

| AF Type | |

| Paroxysmal AF | 22 (73%) |

| Persistent/Long-Standing Persistent AF | 8 (27%) |

| Heart Failure | 3 (10%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 4 (13%) |

| Sleep Apnea | 2 (7%) |

| Hypertension | 16 (53%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 11 (37%) |

| Number of Failed Anti-Arrhythmics | 1.00 ± 0.58 |

| Antiarrhyhmics Used | |

| Amiodarone | 11 (37%) |

| Flecanaide | 7 (23%) |

| Propafenone | 4 (13%) |

| Dronedranone | 3 (10%) |

| Dofetilide | 2 (7%) |

| Sotalol | 2 (7%) |

| Statins Intake | 8 (27%) |

| B-Blocker Intake | 18 (60%) |

| Ca-Channel Blocker Intake | 7 (23%) |

| Left Atrial Volume, in cm3 | 112.1± 31.0 |

BMI: Body Mass Index, AF: Atrial Fibrillation.

EAdT LOCALIZATION

EAdT was located primarily at the pulmonary vein antra: 25 (83%) at the right superior PV, 12 (40%) at the right inferior PV, 14 (47%) at the left superior PV and 16 (53%) at the left inferior PV. In addition, EAdT was variably found on the anterior surface in 9 (30%), posterior surface in 13 (43%), roof in 11 (37%), septal area in 21 (70%), left atrial appendage in 28 (93%) and mitral isthmus in 24 (80%) cases.

ELECTROANATOMIC MAPPING

A total of 4545 points were acquired on EAM of 30 patients. Of all points, 2187 were excluded due to catheter instability or ectopic beats during point acquisition, and the remaining 2358 points (mean of 78.6 points-per-patient) were included for voltage analysis. The mean bipolar voltage was 1.76 mV (median=1.33, IQR[0.642; 2.46]) and the mean unipolar voltage was 2.22 mV (median=1.75, IQR[1.017; 3.093]). Four hundred and twenty-seven points were found to have a bipolar voltage <0.5 mV and were considered as low-voltage zones (LVZ). Low-voltage zones were present in all 30 patients of the cohort.

PREDICTORS OF BIPOLAR VOLTAGE

In the patient-clustered GEE model displayed in Table 2, age, BMI, hypertension, and persistent AF were all significantly and inversely associated with log bipolar voltage on univariable analyses. In addition, male gender was positively associated with log bipolar voltage. In the multivariable GEE model without EAdT, age (−0.02 per year, p=0.02) was the only variable that remained independently associated with log bipolar voltage. In the multivariable GEE model with EAdT, age (−0.01 per year, P=0.04) remained associated with log bipolar voltage although the magnitude of its association was reduced. In the latter model, EAdT was also associated (−0.29, P<0.001) with log bipolar voltage.

TABLE 2.

The univariable and multivariable associations of clinical factors and EAdT with log bipolar voltage

| Univariable | Multivariable without EAdT | Multivariable with EAdT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Age, in years | −0.02 | <0.001 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| Male Gender | 0.37 | 0.006 | 0.13 | 0.43 | 0.15 | 0.37 |

| BMI, in kg/m2 | −0.02 | 0.048 | −0.01 | 0.61 | −0.01 | 0.75 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 2 | −0.19 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.34 |

| Hypertension | −0.27 | 0.03 | −0.23 | 0.20 | −0.23 | 0.20 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | −0.14 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 0.89 | 0.08 | 0.73 |

| Persistent AF | −0.38 | 0.02 | −0.25 | 0.24 | −0.25 | 0.23 |

| Left Atrial Volume | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.63 | −0.01 | 0.57 |

| EAdT | −0.31 | <0.001 | −0.29 | <0.001 | ||

AF: Atrial Fibrillation, BMI: Body Mass Index, EAdT: epicardial adipose tissue.

PREDICTORS OF LOW-VOLTAGE ZONES

To examine a potential non-linear association with voltage, the association of epicardial fat and clinical predictors with low voltage zones was examined. In this multivariable GEE model, age (+0.03 per year, P=0.05) and EAdT (+0.45, P<0.001) were associated with low voltage zones. The results have been summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

The multivariable predictors of low-voltage zones (<0.5 mV)

| Odds Ratio |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, in years | 1.02 | 0.05 |

| Male Gender | 1.47 | 0.23 |

| BMI, in kg/m2 | 0.99 | 0.761 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 2 | 1.15 | 0.845 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1.06 | 0.887 |

| Hypertension | 1.13 | 0.772 |

| Persistent AF | 1.33 | 0.571 |

| Left Atrial Volume | 1.01 | 0.08 |

| EAdT | 1.60 | <0.001 |

AF: Atrial Fibrillation, BMI: Body Mass Index, EAdT: Epicardial Adipose Tissue.

To further understand the association between bipolar voltage and EAdT, we stratified our EAM points into four: normal-voltage (≥0.5 mV) zones without EAdT (area 1), low-voltage zones (<0.5 mV) without EAdT (area 2), normal-voltage zones with EAdT (area 3), and low-voltage zones with EAdT (area 4) as summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Median bipolar voltage was significantly higher in area 1 compared to area 3 (1.788 [1.086; 2.871] vs 1.398 [0.870; 2.546], p<0.00001) and in area 2 compared to area 4 (0.303 [0.198; 0.396] vs 0.252 [0.150;0.369], p=0.007). Although voltage of the myocardium with overlaying EAdT was not always lower than 0.5mV, it was still lower on average than that of myocardium without EAdT.

PREDICTORS OF SIGNAL FRACTIONATION AND WIDENING

In a patient-clustered GEE model, age (OR=1.02 per year, p=0.021), male gender (OR=3.50, p<0.0001), diabetes mellitus (OR=2.91, p=0.0.012), hypertension (OR=2.55, p<0.0001), and presence of EAdT (OR=8.56, p<0.0001) were all significantly and positively associated with fractionated electrograms on multivariable analyses. In a similar manner, age (OR=2.80 per year, p=0.047), male gender (OR=3.00, p=0.027), and presence of EAdT (OR=7.03, p<0.0001) were significantly and positively associated with widened electrograms.

In order to further explore the association between EAdT and electrogram fractionation, we defined four strata: no EAdT with no fractionation (area 1), no EAdT and fractionation (area 2), EAdT with no fractionation (area 3), and EAdT with fractionation (area 4) and we compared average number of electrogram peaks between these areas. The mean number of peaks was significantly different between areas 1 and 3 (3.32±0.76 vs 3.88±0.74, p<0.0001) and between areas 2 and 4 (6.35±0.69 vs 7.05±1.14, p=0.001). We conducted a similar analysis with signal widening. Areas without widening and without EAdT had a significantly shorter duration than areas under EAdT without widening (p<0.001, Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

PREDICTORS OF EPICARDIAL ADIPOSE TISSUE

Six hundred and eighty points were found to have overlaying EAdT. The summary of EAM points co-localized to EAdT stratified by patient characteristics (age tertile, BMI, AF type and history of hypertension) is displayed in Table 4. Patients who were in the second (54 ≤ age ≥ 64) and third tertile of age (>64) had a significantly higher proportion of points with overlaying EAdT (31.85% and 37.92%) than patients who were less than 54 years of age (20.36%, p<0.05 for both). Patients with BMI>30 kg/m2, patients with hypertension, and patients with non-paroxysmal AF had a significantly higher proportion of points with overlaying EAdT than those with BMI ≤ 30, those without hypertension and those with a history of paroxysmal AF (p<0.05). In a multivariable GEE model, only BMI (OR=1.06 per kg/m2, p= 0.01) and age (OR=1.03 per year, p=0.002) were associated with the presence of atrial EAdT.

TABLE 4.

Proportion of EAM points co-localized to EAdT, stratified by tertiles of age, BMI, Hypertension and AF type.

| Variable | % Frequency | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, in years | < 54 | 20.36 | |

| [54 ; 64] | 31.85 | 0.02* | |

| >64 | 37.92 | 0.002* | |

| BMI, in kg/m2 | <30 | 24.72 | 0.004 |

| >30 | 35.52 | ||

| Hypertension | No | 25.71 | 0.04 |

| Yes | 33.64 | ||

| AF Type | PAF | 28.17 | 0.03 |

| Non-PAF | 36.11 | ||

AF: Atrial Fibrillation, BMI: Body Mass Index, EAdT: Epicardial Adipose Tissue.

: comparisons were done with age <54 years.

DISCUSSION

MAIN FINDINGS

The main finding of this study is that intra-cardiac bipolar voltage is inversely associated with age and the presence of overlaying EAdT. Additionally, electrogram fractionation in sinus rhythm is positively associated with age, male gender, diabetes, hypertension, and EAdT. Electrogram widening is associated with age, male gender, and EAdT. BMI and age were associated the presence of EAdT. However, EAdT was not a statistical mediator of the association of clinical variables with atrial scar. Therefore, it appears to associate with the AF electrophysiologic substrate through mechanisms independent of the clinical variables incorporated in our models.

PREDICTORS OF AF SUBSTRATE

The prevalence of AF is known to increase with age.10 By generating an arrhythmic substrate, atrial remodeling likely mediates some of the association between age and arrhythmia burden. Atrial remodeling includes fibrosis, heterogeneity in conduction velocity, shortening of the atrial refractoriness, and subsequent formation of local re-entry circuits and unidirectional block.11 A study conducted by Spach et al. showed that aging is associated with electrical uncoupling of the side-to-side connections between myofibrils leading to a decrease in the "effective" transverse conduction.12 Prior studies have also shown a significant decrease in atrial endocardial bipolar voltage with age.7,13 Furthermore, hypertension is strongly associated with AF incidence.14 By generating a higher afterload, hypertension predisposes to atrial enlargement, electro-mechanical remodeling and a drop in atrial bipolar voltage.15–17 In a study conducted by Medi et al., hypertensive patients were found to have slower conduction velocity, regional conduction delays, lower bipolar voltage and higher propensity to AF compared to non-hypertensive patients.18 Our study suggests another potentially important contributor to AF substrate within the atrium. The presence of adjacent EAdT appears to be associated with reduced bipolar voltage, electrogram fractionation and widening. Importantly, the association between arrhythmogenic substrates and regions with low electrogram amplitude is well established.2,19,20 Histologically, low-voltage zones observed in the setting of AF are characterized by fibrosis.11,21 It is important to note, however, that other etiologies such as poor tissue coupling, reduced thickness of myocardium, non-uniformity of the myocardial tissue (secondary to fatty infiltration or inflammation), and discontinuous conduction may also lead to reduced bipolar voltage.12

EPICARDIAL ADIPOSE TISSUE AND AF SUBSTRATE

The association of epicardial adipose tissue with cardiac arrhythmias has been clearly demonstrated in the literature.22 An analysis of the Framingham Heart cohort involving 3217 participants showed that epicardial fat volume was an independent predictor of AF risk after adjusting for other measures of adiposity and AF risk factors.6 These studies suggest that EAdT may play a role in the generation of a myocardial arrhythmogenic substrate leading to AF. Biochemical studies have demonstrated that EAdT produces pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, monocyte chemotactic-1) and growth factors (such as TGFs and MMPs) with paracrine activity on the myocardium.5,23 These molecules are thought to contribute to the structural remodeling that begets AF, namely fibrosis. In fact, Venteclef et al. showed that human EAdT induced marked fibrosis of rodent atrial myocardium and favored the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts.23 However, very few studies have examined the role of EAdT in atrial remodeling in the setting of AF. In a study by Lin et al., incubation of rabbit atrial myocytes with EAdT modulated the electrophysiological properties of the cells leading to arrhythmias.4 Nagashima et al. showed the close correlation of EAdT with high dominant frequency (DF) sites during AF.24 Since high DF sites indicate local synchronous high-frequency activations likely related to the center of a focal-firing rotor or local reentry circuit, this study suggests that EAdT promotes AF perpetuation. In our study, EAdT had a negative effect on the underlying bipolar voltage in the setting of AF and was independently associated with the presence of low-voltage zones. One potential mechanism for the negative effect of EAdT on electrogram amplitude and fractionation is through fatty deposits in the neighboring myocardium. This hypothesis is based on a study conducted in sheep by Sanders et al. showing that obesity was accompanied by adipose infiltration of contiguous LA muscle leading to reduced local endocardial voltage, conduction abnormalities, and increased propensity for AF.25 To the extent of our knowledge, this is the first in-vivo study of the association of EAdT with the underlying myocardial substrate in the setting of AF.

PREDICTORS OF EAdT

Our findings show that the presence of epicardial fat overlying the left atrium is significantly associated with BMI. In the face of a rising epidemic of obesity, studies have clearly established its close link with AF incidence. In fact, a 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI was shown to increase AF risk by 5–12%.26,27 In a recent meta-analysis, obesity was shown to increase the risk of AF recurrence after an ablation procedure (by 13% for every 5 kg/m2).28 As to the underlying pathophysiology this phenomenon, human studies were challenged by numerous confounders commonly found in obese patients such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obstructive sleep apnea, coronary artery disease, and heart failure, which predispose to AF. In a sheep model, Abed et al. provided a causal relationship between obesity and left atrial changes, namely structural and electrical remodeling (increased atrial size, fibrosis, fatty infiltration, conduction heterogeneity and inducibility of arrhythmia).29 In our study, we accounted for several of the potential confounding factors by inclusion of the CHA2DS2-VASc score along with patients’ clinical covariates and found that BMI was significantly and directly associated with the presence of epicardial fat. Thus, our study provides the foundation for establishing the direct impact of obesity on atrial substrate and AF burden through EAdT deposition.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The association between epicardial fat deposits secondary to obesity and atrial substrate provide a framework supporting the benefit of weight loss on AF reduction. The effect of weight loss on the amount of adipose tissue around the heart has been demonstrated in several studies and several trials have also supported the benefit of weight management on AF burden.30,31 Thus, a preventive strategy incorporating risk factor management should effectively reduce AF burden.

LIMITATIONS

This study has a relatively a small population, restricted to patients undergoing LA voltage mapping as part of an AF ablation procedure. Future studies with larger cohorts as well as denser EAMs may refine and improve the generalizability of our results. In addition, our results might be affected by positional errors when registering EAMs to the LA mesh. However, the extent of error appears to be very low based upon prior validation studies.32 Finally, the use of a linear regression GEE model only ascertains an association and not a relationship of causality between our variables such as EAdT and bipolar voltage. This points to the importance of biochemical studies to demonstrate the mechanistic interaction between EAdT and atrial myocytes.

CONCLUSION

In the setting of AF, myocardial bipolar voltage on electro-anatomic mapping of the atrium is negatively associated with age and the presence of overlying epicardial adipose tissue. Electrogram fractionation in sinus rhythm is positively associated with age, male gender, diabetes, hypertension, and EAdT. Electrogram widening is associated with age, male gender, and EAdT. BMI was directly associated with the presence of EAdT in patients with AF. However, EAdT was not a statistical mediator of the association between clinical variables and LA scar.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant nos. K23HL089333 and R01HL116280) as well as by a Biosense Webster grant to Dr Nazarian; the Roz and Marvin H. Weiner and Family Foundation; the Dr. Francis P. Chiaramonte Foundation; Marilyn and Christian Poindexter; and the Norbert and Louise Grunwald Cardiac Arrhythmia Research Fund.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Dr Nazarian is a scientific advisor to CardioSolv and Biosense Webster as well as a principal investigator for research funding to Johns Hopkins University from Biosense Webster.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Calkins H, Kuck KH, Cappato R, et al. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS Expert Consensus Statement on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation: recommendations for patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and follow-up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design. Europace. 2012 Apr;14(4):528–606. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nademanee K, McKenzie J, Kosar E, Schwab M, Sunsaneewitayakul B, Vasavakul T, Khunnawat C, Ngarmukos T. A new approach for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: mapping of the electrophysiologic substrate. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2044–2053. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts-Thomson KC, Kistler PM, Sanders P, Morton JB, Haqqani HM, Stevenson I, Vohra JK, Sparks PB, Kalman JM. Fractionated atrial electrograms during sinus rhythm: relationship to age, voltage, and conduction velocity. Heart rhythm. 2009;6:587–591. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin YK, Chen YC, Chen JH, Chen SA, Chen YJ. Adipocytes modulate the electrophysiology of atrial myocytes: implications in obesity-induced atrial fibrillation. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107:293. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazurek T, Zhang L, Zalewski A, et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue is a source of inflammatory mediators. Circulation. 2003;108:2460–2466. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099542.57313.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quan KJ, Lee JH, Van Hare GF, Biblo LA, Mackall JA, Carlson MD. Identification and characterization of atrioventricular parasympathetic innervation in humans. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:735–739. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kistler PM, Sanders P, Fynn SP, Stevenson IH, Spence SJ, Vohra JK, Sparks PB, Kalman JM. Electrophysiologic and electroanatomic changes in the human atrium associated with age. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexopoulos N, McLean DS, Janik M, Arepalli CD, Stillman AE, Raggi P. Epicardial adipose tissue and coronary artery plaque characteristics. Atherosclerosis. 2010;210:150–154. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saghy L, Callans DJ, Garcia F, et al. Is there a relationship between complex fractionated atrial electrograms recorded during atrial fibrillation and sinus rhythm fractionation? Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;271:840–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schotten U, Verheule S, Kirchhof P, Goette A. Pathophysiological mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: a translational appraisal. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:265–325. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spach MS, Dolber PC. Relating extracellular potentials and their derivatives to anisotropic propagation at a microscopic level in human cardiac muscle. Evidence for electrical uncoupling of side-to-side fiber connections with increasing age. Circ Res. 1986;58:356–371. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuan TC, Chang SL, Tsao HM, et al. The impact of age on the electroanatomical characteristics and outcome of catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;2:966–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunner KJ, Bunch TJ, Mullin CM, May HT, Bair TL, Elliot DW, Anderson JL, Mahapatra S. Clinical predictors of risk for atrial fibrillation: implications for diagnosis and monitoring. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:1498–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lau DH, Mackenzie L, Kelly DJ, et al. Short-term hypertension is associated with the development of atrial fibrillation substrate: a study in an ovine hypertensive model. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang T, Xia YL, Zhang SL, Gao LJ, Xie ZZ, Yang YZ, Zhao J. The impact of hypertension on the electromechanical properties and outcome of catheter ablation in atrial fibrillation patients. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:913–920. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.06.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaziri SM, Larson MG, Lauer MS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Influence of blood pressure on left atrial size. The Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension. 1995;25:1155–1160. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.6.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medi C, Kalman JM, Spence SJ, Teh AW, Lee G, Bader I, Kaye DM, Kistler PM. Atrial electrical and structural changes associated with longstanding hypertension in humans: implications for the substrate for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22:1317–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2011.02125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wijffels MC, Kirchhof CJ, Dorland R, Allessie MA. Atrial fibrillation begets atrial fibrillation. A study in awake chronically instrumented goats. Circulation. 1995;92:1954–1968. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verma A, Wazni OM, Marrouche NF, et al. Pre-existent left atrial scarring in patients undergoing pulmonary vein antrum isolation: an independent predictor of procedural failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:285–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kostin S, Klein G, Szalay Z, Hein S, Bauer EP, Schaper J. Structural correlate of atrial fibrillation in human patients. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:361–379. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00273-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al Chekakie MO, Welles CC, Metoyer R, Ibrahim A, Shapira AR, Cytron J, Santucci P, Wilber DJ, Akar JG. Pericardial fat is independently associated with human atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:784–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venteclef N, Guglielmi V, Balse E, Gaborit B, Cotillard A, Atassi F, Amour J, Leprince P, Dutour A, Clement K, Hatem SN. Human epicardial adipose tissue induces fibrosis of the atrial myocardium through the secretion of adipo-fibrokines. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:795a–805a. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagashima K, Okumura Y, Watanabe I, Nakai T, Ohkubo K, Kofune M, Mano H, Sonoda K, Hiro T, Nikaido M, Hirayama A. Does location of epicardial adipose tissue correspond to endocardial high dominant frequency or complex fractionated atrial electrogram sites during atrial fibrillation? Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:676–683. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.971200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahajan R, Lau DH, Brooks AG, et al. Electrophysiological, Electroanatomical, and Structural Remodeling of the Atria as Consequences of Sustained Obesity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tedrow UB, Conen D, Ridker PM, Cook NR, Koplan BA, Manson JE, Buring JE, Albert CM. The long- and short-term impact of elevated body mass index on the risk of new atrial fibrillation the WHS (women's health study) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2319–2327. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez MV, Wang PJ, Larson JC, et al. Risk factors for atrial fibrillation and their population burden in postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Heart. 2013;99:1173–1178. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong CX, Sullivan T, Sun MT, Mahajan R, Pathak RK, Middeldorp M, Twomey D, Ganesan AN, Rangnekar G, Roberts-Thomson KC, Lau DH, Sanders P. Obesity and the Risk of Incident, Post-Operative, and Post-Ablation Atrial Fibrillation: A Meta-Analysis of 626,603 Individuals in 51 Studies. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;1:139–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abed HS, Samuel CS, Lau DH, et al. Obesity results in progressive atrial structural and electrical remodeling: implications for atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabkin SW, Campbell H. Comparison of reducing epicardial fat by exercise, diet or bariatric surgery weight loss strategies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:406–415. doi: 10.1111/obr.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abed HS, Wittert GA, Leong DP, et al. Effect of weight reduction and cardiometabolic risk factor management on symptom burden and severity in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2050–2060. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong J, Calkins H, Solomon SB, Lai S, Dalal D, Lardo AC, Brem E, Preiss A, Berger RD, Halperin H, Dickfeld T. Integrated electroanatomic mapping with three-dimensional computed tomographic images for real-time guided ablations. Circulation. 2006;113:186–194. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.565200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.