Abstract

Aims and objectives

The current study examined the coping styles used by sexual minority men who have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV), including sexual, emotional, and physical victimization, as well as physical injury.

Background

While sexual minority men experience IPV at least as often as do heterosexuals, there is currently limited knowledge of IPV in this community or resources for sexual minority men who experience IPV.

Design

Cross-sectional design.

Method

Sexual minority men (N= 89) were recruited as part of a national online survey and completed questionnaires assessing lifetime experiences of IPV as well as various coping strategies. In terms of IPV, 34.8% of participants reported having been targets of sexual abuse, 38.2% targets of physical abuse, 69.7% targets of psychological abuse, and 28.1% had experienced an injury as a result of IPV during their lifetime.

Results

Canonical correlation analyses found that IPV victimization explained 32.5% of the variance in adaptive and 31.4% of the variance in maladaptive coping behaviors. In the adaptive coping canonical correlation, standardized loadings suggested that sexual minority men who experienced IPV resulting in injury were more likely to use religious coping, but less likely to use planning coping. In the maladaptive coping canonical correlation, sexual minority men who had been targets of intimate partner sexual victimization and IPV resulting in injury tended to engage in increased behavioral disengagement coping.

Conclusion

This study revealed several coping behaviors that are more or less likely as the severity of different forms of IPV increases.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

The identification of these coping styles could be applied to the development and modification of evidence-based interventions to foster effective and discourage ineffective coping styles, thereby improving outcomes for sexual minority men who experience IPV.

Keywords: coping, domestic violence, gender, intimate partner violence (IPV), sexuality

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has been recognized as a problem affecting 30% of women worldwide (World Health Organization, 2013) and approximately 22% of women in the United States (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2010). Unfortunately there is little knowledge of or resources for men who experience IPV, or for those of either gender in same-sex relationships. While researchers have begun to examine IPV in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community, much of the literature continues to focus on women due to the stereotype that only women can experience IPV and only men can be perpetrators (Brown, 2008). Sexual minority men therefore are overlooked on two counts: their gender and sexual orientation. This is especially problematic given that research has found that gay men experience IPV more often than lesbian women (Messinger, 2011). IPV victimization also occurs in sexual minority men at least as often as in heterosexuals, with the lifetime prevalence for sexual violence victimization being 40.2% and 47.4% for gay and bisexual men, respectively, and the lifetime prevalence for physical violence being 26.0% and 37.3% (Walters, Chen, & Breiding, 2013).

Background

Researchers have only begun to examine IPV in sexual minority men, with most research focusing on prevalence or the roles of various factors such as masculinity and heteronormativity in IPV (Finneran & Stephenson, 2014; Kay & Jeffries, 2010). There remains a dearth of studies examining coping mechanisms used by sexual minority men when they experience IPV. Coping, which can be defined as cognitive and behavioral strategies used to manage stress (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004), influences how an experience impacts an individual and can affect health and a variety of other outcomes (Carver & Vargas, 2011).

Outside of IPV research, various coping styles have been identified as adaptive or maladaptive. Coping that involves acceptance, positive reframing, and humor has been found to be related to less distress, while coping that involves denial and behavioral disengagement has been associated with greater distress (Carver et al., 1993). Generally, approach or engagement coping (i.e., planning, acceptance, positive reframing, emotional and instrumental support) has been found to be adaptive, while avoidance or disengagement coping (i.e., self-distraction, denial, substance use, behavioral disengagement) is often dysfunctional and maladaptive (Carver & Vargas, 2011). Seeking social support is another adaptive coping strategy that has been linked to reduced distress (Taylor, 2011).

Literature on coping mechanisms used by sexual minority men who experience IPV is virtually nonexistent; instead, most of the literature examining coping with IPV focuses on women. Calvete and colleagues (2008) found that disengagement coping partially mediated the effect of psychological IPV victimization on anxiety and depression in women, with higher disengagement leading to greater anxiety and depression. Another study found that avoidant coping was associated with PTSD symptoms one year after IPV in women (Krause, Kaltman, Goodman, & Dutton, 2008). Women who experience IPV have been shown to use reframing and active coping (Zink et al., 2006), but turn to avoidance as the severity of violence increases and social support decreases (Waldrop & Resnick, 2004). Women who experience IPV have also been found to use alcohol (Kaysen et al., 2007), problem solving coping, and social support coping (Haesler, 2013). One of the few studies examining sexual minority men found that those who had experienced IPV were more likely to engage in substance use than those who had not (Buller, Devries, Howard, & Bacchus, 2014).

Differences in coping strategies and their consequences have been documented in regards to both gender and sexual orientation (Hvidtjørn et al., 2014; Rostosky, Danner, & Riggle, 2007), highlighting the need to explore how sexual minority men cope, as it may not be the same as in heterosexual women. Schmied and colleagues (2015) found that when faced with severe stressors, compared to men, women were more likely to use denial, self-blame, and positive reinterpretation and had higher posttraumatic stress symptoms (Schmied et al., 2015). Gender differences have been found in the use of religious coping as well, with women reporting higher levels of religiosity and greater use of positive religious coping, while men tend to use more negative religious coping (Hvidtjørn et al., 2014). As for differences by sexual orientation, some studies suggest that the protective effects of religious coping in heterosexuals, such as better mental health and decreased substance use, are absent for the LGBT community (Rostosky et al., 2007).

The current study examines the positive and negative coping styles used by sexual minority men who have experienced IPV, including sexual, emotional, and physical victimization, as well as physical injury. It is important to study coping in this particular population due to the high rates of IPV in sexual minority men as well as the evidence that coping styles may be different for men compared to women (Schmied et al., 2015) and for sexual minorities compared to heterosexual individuals (Rostosky et al., 2007). Furthermore, research on coping with IPV in sexual minority men has the potential to inform domestic violence advocacy and intervention that can aid in survivors’ abilities to cope with IPV. The current study is mostly exploratory. However, based on past literature that suggests social support decreases as severity of IPV increases (Waldrop & Resnick, 2004) and IPV severity is associated with increased substance use and behavioral disengagement (Buller et al., 2014; Waldrop & Resnick, 2004), we propose three general hypotheses: (a) IPV victimization will be negatively associated with social support coping, (b) IPV severity will be associated with increased substance use, and (c) IPV severity will be associated with increased behavioral disengagement.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N = 89) were recruited as part of a national survey on sexual minority men. To be included, participants had to be at least 18 years old and identify as sexual minority men. Participants had a mean age of 30.7 years (SD = 10.30). They indicated their sexual orientation by selecting from the following response options: gay (61.8%), bisexual (25.8%), queer (11.2%), and “other” (1.1%) non-heterosexual orientation. Information about racial/ethnic identity, education, and relationship status are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Information.

| Demographics | % |

|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White/European-American (non-Latino) | 28.1 |

| Asian/Asian-American/Pacific Islander | 27.0 |

| Black/African-American (non-Latino) | 22.5 |

| Latino/Hispanic | 7.9 |

| American-Indian/Native-American | 4.5 |

| Multiracial/Multiethnic | 10.1 |

| Education | |

| High school/GED | 6.7 |

| Some college (no degree) | 27.0 |

| 2-year/technical degree | 7.9 |

| 4-year college degree | 37.1 |

| Master’s degree | 18.0 |

| Doctorate degree | 3.4 |

| Relationship status | |

| Long-term relationship (>12 months) with 1 person | 36.0 |

| New relationship (< 12 months) with 1 person | 11.2 |

| Dating/in a relationship with more than 1 person | 14.6 |

| Not currently dating or in a relationship | 38.2 |

Measures

Participants completed the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale, Short-Form (Straus & Douglas, 2004) to assess experiences with intimate partner violence and the Brief COPE (Carver, 1997) to assess coping styles used. A researcher-created questionnaire was then administered to collect demographic information.

Revised Conflict Tactics Scale, Short-Form (CTS2S)

The CTS2S contains 10 items assessing one’s experiences as the target of IPV (Straus & Douglas, 2004). The scale instructs respondents to indicate how often their partner engaged in various behaviors (i.e., “My partner pushed, shoved, or slapped me”). Items correspond to four types of IPV: Physical Assault, Injury, Psychological Aggression, and Sexual Coercion. Additionally, a Negotiation subscale reflects healthy conflict tactics and was not used in the current study. Responses from 1 (“once in the past year”) to 6 (“more than 20 times in the past year”) indicate frequency of the abuse within the past year, while a response of 7 (“not in the past year, but it did happen before”) suggests lifetime prevalence, and a response of 8 (“this has never happened”) indicates the absence of abuse. Responses of 1–7 were recoded as 1 (“lifetime prevalence”), while 8 was recoded as 0 (“absence”). Scores were them summed for each category of IPV, resulting in scores of 0 (“no IPV”), 1, or 2. This scale has commonly been used to measure intimate partner violence (Edwards, Dixon, Gidycz, & Desai, 2014; Hines & Douglas, 2016; Lyons, Bell, Frechette, & Romano, 2015).

Brief COPE

The Brief COPE (Carver, 1997) is a 28-item questionnaire that measures coping styles. It consists of 14 scales each composed of two items: Active Coping (α = .68), Planning (α = .73), Positive Reframing (α = .64), Acceptance (α = .57), Humor (α = .73), Religion (α = .82), Using Emotional Support (α = .71), Using Instrumental Support (α = .64), Self-Distraction (α = .71), Denial (α = .54), Venting (α = .50), Substance Use (α = .90), Behavioral Disengagement (α = .65), and Self-Blame (α = .69). Respondents indicated the extent to which they have been engaging in the behavior described by each item using a Likert-type rating scale from 1 (“I haven’t been doing this at all”) to 4 (“I’ve been doing this a lot”). Higher scores for each subscale indicate increased coping of that form. The Brief COPE is a frequently used scale to measure coping styles in diverse populations (Gattino, Rollero, & De Piccoli, 2015; Read, Griffin, Wardell, & Ouimette, 2014; Wong et al., 2016).

Procedure

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Virginia Commonwealth University. Participants were recruited for a confidential, online survey through a number of internet forums and groups. National and regional LGBT organizations (e.g., National Gay Black Men’s Advocacy Coalition, The Center Orlando) and online LGBT social and community groups (e.g., LGBT People of Color Yahoo group) were contacted via email with information regarding recruitment for a study assessing the health of sexual minority men. Similar information was posted to online social and community groups’ message boards for groups that allowed such activity or was submitted to group moderators for those that did not allow non-member posting. If approved by the group moderator, study and contact information was posted to community message boards or sent out to the listserv. These organizations and groups were specifically targeted because they appeared to cater to sexual minority men from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds.

Participants interested in the study were asked to email the study coordinator who screened participants through a response email asking those interested how they met criteria for the study. Individuals who did not respond, provided nonsensical answers, did not meet the inclusion criteria, or appeared to be a computer program were not permitted to participate. For those deemed eligible, the study coordinator provided a link by email, as well a unique code, to access the online survey. An automatic deletion process was used to safeguard against the high likelihood of obtaining false responses when conducting online research involving participant incentives. Responses were automatically deleted from the survey if there was any indication of false responding, such as completion time of less than 20 minutes or greater than 24 hours; for implausible response patterns, such as selecting the first response for every single item on a scale; or if participants did not respond to at least 4 of 6 randomly inserted accuracy checks correctly (e.g., “Please select strongly agree for this item”).

All participants fully consented prior to participation in the IRB-approved study. Participants were compensated with a $15 Amazon.com electronic gift card funded through departmental funds. At the end of the survey, participants input an email address to which they wanted their gift card sent. A financial administrator who did not have access to any participant data compensated participants within approximately seven days of survey completion.

Data Analysis

In the current study, adaptive coping variables included active coping, planning, positive reframing, acceptance, humor, religion, using emotional support, and using instrumental support. Maladaptive coping variables included self-distraction, denial, venting, substance use, behavioral disengagement, and self-blame. IPV variables were the four subtypes of IPV: physical assault, injury, psychological aggression, and sexual coercion.

To evaluate which coping styles were most associated with having experienced various forms of IPV, two canonical correlation analyses were performed, one assessing adaptive and one assessing maladaptive coping styles. A canonical correlation assesses the relationship between two sets of variables, in this case IPV (physical, sexual, psychological, and injury) and coping styles (see above for the various adaptive and maladaptive styles) of sexual minority men. It pulls the shared variance from both variable sets to create a canonical correlation coefficient (r) and calculates a number of correlations equal to the number of variables measured in the smaller of the two variable sets. In the current study, the IPV variable set contained four variables, so four canonical correlations were produced. The first canonical correlation always has the largest value and will be the focus of the analyses. Standardized canonical loadings from each variable set were used to identify the most significant pattern of connections among indices of these larger constructs. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 22.

Results

In terms of IPV, 34.8% of participants reported having been targets of sexual abuse, 38.2% had been targets of physical abuse, 69.7% had been targets of psychological abuse, and 28.1% had experienced an injury as a result of IPV during their lifetime. All variables were examined for accuracy of data entry, missing values, univariate and multivariate outliers, normality, linearity, homoscedasticity, multicollinearity, and singularity. All assumptions of normality were met.

Correlation Matrix

A correlation matrix was calculated showing all of the bivariate relationships among variables in the current study (Table 2). All four types of IPV were significantly and positively associated with denial, behavioral disengagement, and religious coping. Sexual and physical victimization as well as IPV resulting in injury were all significantly and negatively associated with active coping, planning coping, positive reframing, and acceptance coping.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations between IPV and Coping Styles.

| Coping Style | Psychological Abuse | Sexual Abuse | Physical Abuse | Injury |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | −.107 | −.294** | −.251* | −.312** |

| Planning | −.104 | −.328** | −.279** | −.376** |

| Positive Reframing | −.193 | −.212* | −.282** | −.303** |

| Acceptance | −.099 | −.293** | −.238* | −.246* |

| Humor | .029 | .030 | −.010 | .005 |

| Religious | .239* | .212* | .275** | .220* |

| Emotional Support | .011 | −.012 | −.065 | .008 |

| Instrumental Support | −.091 | −.155 | −.185 | −.160 |

| Self-Distraction | −.012 | −.144 | −.116 | −.184 |

| Denial | .242* | .256* | .214* | .281** |

| Venting | −.045 | .002 | −.047 | −.005 |

| Substance Use | .049 | .187 | .185 | .138 |

| Behavioral Disengagement | .287** | .485** | .400** | .460** |

| Self-Blame | .108 | .124 | .131 | .111 |

Note.

= p < .05;

= p < .01.

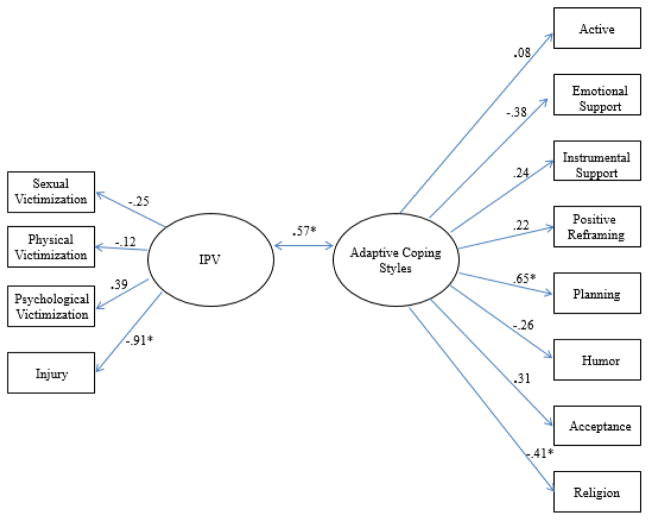

Adaptive Coping Styles

The canonical correlation examining the association between IPV victimization and adaptive coping styles was .57 (32.5% overlapping variance), λ = .529, χ2(32) = 51.88, p = .015. Canonical correlations two through four were not significant and will not be interpreted. Standardized canonical coefficients were used to examine the relative contribution of each variable to the overall canonical correlation (Figure 1). In the first canonical correlation, the standardized canonical coefficients for the IPV victimization variables showed that injury loaded most highly (−.912), followed by psychological victimization (.393), sexual victimization (−.253), and physical victimization (−.120). Because the coefficient reflecting injury was above the conventional cutoff of .40, this variable will be focused on for interpretation. For the adaptive coping variables, planning loaded most highly (.649), followed by religious coping (−.414). All other coefficients were below .40.

Figure 1.

Canonical correlation between IPV and adaptive coping styles.

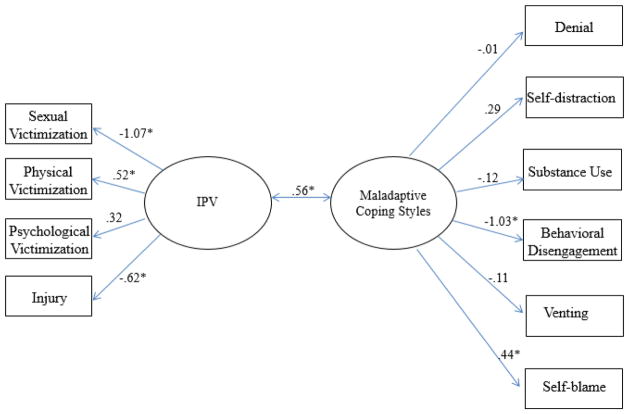

Maladaptive Coping Styles

The canonical correlation examining the association between IPV victimization and maladaptive coping styles was .56 (31.4% overlapping variance), λ = .607, χ2(24) = 41.24, p = .016. Again, canonical correlations two through four were not significant and will not be interpreted. Standardized canonical coefficients were used to examine the relative contribution of each variable to the overall canonical correlation (Figure 2). In the first canonical correlation for maladaptive coping styles, the standardized canonical coefficients for IPV victimization showed that sexual victimization loaded most highly (−1.07), followed by injury (−.620) and physical victimization (.520), with the other coefficient below the cutoff of .40. For the maladaptive coping styles, behavioral disengagement loaded most highly (−1.034), followed by self-blame (.444). All other coefficients were below .40.

Figure 2.

Canonical correlation between IPV and maladaptive coping styles.

Discussion

Adaptive Coping Behaviors

In the adaptive coping canonical correlation, standardized loadings suggested that sexual minority men who experienced IPV resulting in injury were more likely to use religious coping, but less likely to use planning coping. It was predicted that use of social support coping (instrumental and emotional) would decrease as the severity of IPV victimization increased, as was found in past research (Waldrop & Resnick, 2004). This hypothesis was not supported by the data. Instead, no association was found between instrumental or emotional support coping and the severity of IPV victimization. Although past studies have found that women who experience IPV use social support (Carver & Vargas, 2011; Taylor, 2011), sexual minority men may have difficulty using social support given the high levels of stigma that sexual minority men encounter in general and probably especially when experiencing IPV. It may be particularly difficult for sexual minority men to seek support if they have not come out1 to potential sources of support. IPV, unlike many other problems, requires discussion of one’s romantic relationship, thereby requiring sexual minority men to disclose their sexual orientation.

While past findings have suggested that men engage in religious coping to a lesser extent than women (Hvidtjørn et al., 2014; Pargament, Smith, Koenig, & Perez, 1998) and LGBT individuals may not benefit from religious coping (Rostosky et al., 2007), results of the present study suggest that sexual minority men do in fact use religious coping to a greater extent as the severity of IPV victimization resulting in injury increases. Perhaps, as one study suggests, some sexual minority men are able to find positive and nurturing aspects in religion (Kubicek et al., 2009) and therefore turn to religious coping in challenging times.

The present study suggested that IPV resulting in injury is associated with decreased planning coping. This is somewhat surprising, as past studies examining female samples have found that as IPV severity increased, so did planning behavior (Goodkind, Sullivan, & Bybee, 2004). Examples of planning coping in the context of IPV include creating a safety plan to protect oneself from the abuser, making plans to leave the abuser, or storing an emergency fund outside of the home to ensure financial stability outside of the abusive relationship (Meyer, Wagner, & Dutton, 2010). Planning coping has been identified in past research as an effective coping tool (Carver & Vargas, 2011).

Maladaptive Coping Behaviors

In the maladaptive coping canonical correlation, although physical victimization loaded above the .40 magnitude threshold, it loaded in the opposite direction as what would be expected based on the patterns of findings in the bivariate correlations. Similarly, self-blame loaded above this threshold but had not shown statistically significant relationships with any form of IPV in the bivariate correlations. Therefore, both of these loadings are likely due to a suppressor effect. As a result, they should be interpreted as error instead of as true effects. Suppressors can occur when a predictor in a multivariate analysis is correlated with another predictor but is not correlated or only weakly correlated with a dependent variable. Ludlow and Klein (2014) point out that “in this situation the regression coefficient . . . may be diminished or enhanced and even reversed in sign” (p. 1). If suppressors do not occur as a result of interventions designed to produce the effect, or if they are not theoretically justified, they are better seen as “a statistical effect potentially devoid of substantive interpretation” (Ludlow & Klein, 2014, p. 2). Removing physical victimization and self-blame from the interpretation, we can now say that the pattern of shared variance in the canonical correlation suggests that sexual minority men who had been targets of intimate partner sexual victimization and IPV resulting in injury tended to engage in increased behavioral disengagement coping.

Although past studies have suggested that both male (Buller et al., 2014) and female (Kaysen et al., 2007) targets of IPV engage in substance use to cope with IPV, this was not supported in the current study in either the bivariate or canonical correlations. Our second hypothesis regarding maladaptive coping strategies was that as the severity of IPV increased, so would behavioral disengagement, and this was supported. This suggests that just as women use more avoidance coping as the severity of violence increases (Waldrop & Resnick, 2004), so do sexual minority men. Behavioral disengagement has been associated with greater distress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD in the short- and long-term (Calvete et al., 2008; Carver & Vargas, 2011; Krause et al., 2008). For example, a study of men who had experienced childhood sexual abuse found that disengagement coping was associated with long-term psychological problems (O’Leary, 2009).

Behavioral disengagement was associated with being the target of sexual IPV or IPV resulting in injury. In this study, 34.8% of sexual minority men reported having been targets of sexual abuse, and 28.1% had experienced an injury as a result of IPV during their lifetime. Other studies have reported similar rates of these forms of IPV (Greenwood et al., 2002; Messinger, 2010; Zahnd et al., 2010). One study found that nearly half of the sexual minority men surveyed had experienced near-lethal violence by an intimate partner (Loveland & Raghavan, 2014). Unfortunately, although IPV is common among sexual minority men, it may not always be recognized as such by society or even by the target of IPV due to heterosexism and gender role messages that have created myths regarding who can be a target versus perpetrator of IPV (Brown, 2008; Seelau, Seelau, & Poorman, 2003). Studies have demonstrated that IPV against women is perceived as more serious, more believable, and more worthy of intervention than IPV against men (Seelau et al., 2003). Furthermore, male targets of IPV have fewer resources available to them (Houston & McKirnan, 2007; Merrill & Wolfe, 2000).

Relevance to Clinical Practice

Future clinical practice research should explore barriers to the use of emotional and instrumental support by sexual minority men who experience IPV, as both forms of social support have been found in past studies to be associated with decreased distress (Carver & Vargas, 2011; Taylor, 2011) and therefore may improve outcomes for sexual minority men experiencing IPV. In the current study, 34.8% of participants reported having been targets of sexual abuse, 38.2% were targets of physical abuse, 69.7% were targets of psychological abuse, and 28.1% had experienced an injury as a result of IPV during their lifetime. These rates are higher than national and international estimates of IPV victimization in women (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2010; World Health Organization, 2013), and as a result, clinicians may benefit from screening for IPV victimization in their patients who are sexual minority men.

Researchers have found that for women targets of IPV, social support protects against negative mental health outcomes, such as depression and PTSD, and also increases a women’s sense of self-efficacy, bolstering the impact of problem-focused coping efforts (Kocult & Goodman, 2003). In addition, survivors of IPV who report high levels of social support are less likely to experience re-abuse (Goodman, Dutton, Vankos, & Weinfurt, 2005). Psychoeducation about the role of social support in conjunction with skills training, such as teaching interpersonal effectiveness, could improve sexual minority men’s ability to ask for emotional or instrumental support when it is available.

Future clinical practice research is also needed to examine the impact of using religious coping in this population, as religiosity in sexual minority adults has actually been linked to higher levels of internalized homophobia (Clayman, 2005; Gattis, Woodford, & Han, 2014). Mixed findings have emerged regarding whether religiosity serves as a protective or risk factor for mental health problems in the LGBT community (Lease, Horne, & Noffsinger-Frazier, 2005; Rabinovich, Perrin, Tabaac, & Brewster, 2015).

One possible reason for decreased planning coping in the context of IPV resulting in injury in the current study is that although a number of community resources exist for women targets of IPV, similar resources are less prevalent for men who experience IPV (Houston & McKirnan, 2007; Merrill & Wolfe, 2000), and perhaps especially so for sexual minority men given high levels of stigma they experience. Further research is needed to understand the emotional and health outcomes of decreased planning coping in sexual minority men who have experienced IPV, and also the ways to increase resources for sexual minority men who do engage in planning coping.

Future research may aim to understand the impact of disengagement coping on sexual minority men’s emotional outcomes. If disengagement coping is found to be linked to negative outcomes in this population, future studies might develop and examine the effectiveness of interventions designed to discourage this form of coping and replace it with more adaptive forms. In particular, techniques such as motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) could be employed to help sexual minority men who have experienced IPV develop their own internal motivation to select adaptive coping strategies and abandon negative ones.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study has several limitations which suggest directions for future research. While diverse, the sample was somewhat small, limiting the generalizability of the results. Mendoza, Markos, and Gonter (1978) found that if there are strong canonical correlations in the data (e.g., r > .7, as in the current study), then even relatively small samples (e.g., n = 50) will detect them most of the time. However, other researchers have recommended 20 to 60 times as many cases as variables in the analysis (Barcikowski & Stevens, 1975; Stevens, 1986). Therefore, while the sample was sufficient, the study may have been improved with a larger sample size. It is suggested that these findings be replicated with a larger sample.

Another limitation is that the study did not ask participants to disclose how often they used the various coping strategies specifically in regards to IPV or any other explicit stressor, but rather how often they were used in general. It is possible that individuals use different coping strategies for different stressors, and therefore future studies could measure not only one’s general coping behaviors, but also which are used specifically to cope with IPV victimization.

Future directions for research include identifying facilitators and barriers to various coping strategies, as well as how these coping strategies impact health outcomes. For example, studies may aim to identify barriers to the utilization of positive reframing, planning, social support, active coping, and acceptance in order to facilitate increased use of these adaptive coping styles. Further research is also needed to understand the emotional and health outcomes of various coping strategies in sexual minority men targets of IPV, as research examining outcomes of these strategies is limited to women and non-IPV samples. If interventions are developed to increase positive and decrease negative coping behaviors, future studies should evaluate these interventions to ensure that they are effective. Similarly, given the extremely high rates of IPV reported in the current sample, community resources catering to sexual minority men after IPV are critical, especially since past research has identified very few resources for men who experience IPV (Houston & McKirnan, 2007; Merrill & Wolfe, 2000). Finally, it could be beneficial in achieving these research aims to employ community-based participatory research, in which sexual minority men who have experienced IPV could assess the relevance of any interventions or community resources developed as a result of the research.

Conclusion

This study addressed the dearth of information on the coping strategies of sexual minority men who have experienced IPV, revealing several coping behaviors that are more or less likely as the severity of different forms of IPV increases. There remains much to be learned about sexual minority men’s motivations for using these coping strategies, as well as how they impact mental and physical health outcomes. This is a critical area of inquiry, as studies like the current one have the potential to aid in the development and modification of interventions to improve the quality of life of sexual minority men who have experienced IPV.

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

Our findings indicate that 34.8% of sexual minority men in this study have been targets of sexual abuse, 38.2% targets of physical abuse, 69.7% targets of psychological abuse, and 28.1% experienced an injury as a result of IPV during their lifetime.

Sexual minority men who have been targets of IPV resulting in injury were more likely to use religious coping and less likely to use planning coping, while those who have been targets of intimate partner sexual victimization tended to engage in increased behavioral disengagement coping.

Acknowledgments

The survey software for this study was funded by award number UL1TR000058 from the National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

‘Out’ refers to disclosure of sexual minority identity to others.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Lisa D. Goldberg-Looney, Virginia Commonwealth University

Paul B. Perrin, Virginia Commonwealth University

Daniel J. Snipes, Virginia Commonwealth University

Jenna M. Calton, George Mason University

References

- Abel MH. Humor, stress, and coping strategies. Humor. 2002;15(4):365–381. [Google Scholar]

- Barcikowski R, Stevens JP. A Monte Carlo study of the stability of canonical correlations, canonical weights, and canonical variate-variable correlations. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1975;10:353–364. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr1003_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. Gender role implications on same-sex intimate partner abuse. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:457–462. [Google Scholar]

- Buller AM, Devries KM, Howard LM, Bacchus LJ. Associations between intimate partner violence and health among men who have sex with me: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine. 2014;11(3):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete E, Corral S, Estevez A. Cognitive and coping mechanisms in the interplay between intimate partner violence and depression. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 2007;20(4):369–382. doi: 10.1080/10615800701628850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Prozo C, Harris SD, Noriega V, Scheier MF, Robinson DS, … Clark KC. How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: A study of women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:375–390. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Vargas S. Stress, coping, and health. In: Friedman HS, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2011. pp. 162–188. [Google Scholar]

- Clayman SL. The relationship among disclosure, internalized homophobia, religiosity, and psychological well-being in a lesbian population. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2005;66:546. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Dixon KJ, Gidycz CA, Desai AD. Family-of-origin violence and college men’s reports of intimate partner violence perpetration in adolescence and young adulthood: The role of maladaptive interpersonal patterns. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2014;15(2):234–240. [Google Scholar]

- Finneran C, Stephenson R. Intimate partner violence, minority stress, and sexual risk taking among U.S. men who have sex with men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2014;61:288–306. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2013.839911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:745–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattino S, Rollero C, De Piccoli N. The influence of coping strategies on quality of life from a gender perspective. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2015;10(4):689–701. [Google Scholar]

- Gattis MN, Woodford MR, Han Y. Discrimination and depressive symptoms among sexual minority youth: Is gay-affirming religious affiliation a protective factor? Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43:1589–1599. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0342-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind J, Sullivan CM, Bybee D. A contextual analysis of battered women’s safety planning. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:514–533. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman L, Dutton MA, Vankos N, Weinfurt K. Women’s resources and use of strategies as risk and protective factors for reabuse over time. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:311–336. doi: 10.1177/1077801204273297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood GL, Relf MV, Huang B, Pollack LM, Canchola JA, Cantania JA. Battering victimization among a probability-based sample of men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(12):1964–1969. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.12.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haesler LA. Women’s coping experiences in the spectrum of domestic violence abuse. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work. 2013;10:33–43. doi: 10.1080/15433714.2013.750551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA, Douglas EM. Relative influence of various forms of partner violence on the health of male victims: Study of a help seeking sample. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2016;17(1):3–16. doi: 10.1037/a0038999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston E, McKirnan D. Intimate partner abuse among gay and bisexual men: Risk correlates and health outcomes. Journal of Urban Health. 2007;84(5):681–690. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hvidtjørn D, Hjelmborg J, Skytthe A, Christensen K, Hvidt NC. Religiousness and religious coping in a secular society: The gender perspective. Journal of Religion and Health. 2014;53:1329–1341. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9724-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay M, Jeffries S. Homophobia, heteronormativism and hegemonic masculinity: Male same-sex intimate violence from the perspective of Brisbane service providers. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. 2010;17(3):412–423. [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Dillworth TM, Simpson T, Waldrop A, Larimer ME, Resnick PA. Domestic violence and alcohol use: Trauma-related symptoms and motives for drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1272–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocut T, Goodman L. The roles of coping and social support in battered women’s mental health. Violence Against Women. 2003;9(3):323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Krause ED, Kaltman S, Goodman LA, Dutton MA. Avoidant coping and PTSD symptoms related to domestic violence exposure A longitudinal study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21(1):83–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, McDavitt B, Carpineto J, Weiss G, Iverson EF, Kipke MD. God made me gay for a reason: Young men who have sex with men’s resiliency in resolving internalized homophobia from religious sources. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2009;24(5):601–633. doi: 10.1177/0743558409341078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lease LH, Horne SG, Noffsinger-Frazier N. Affirming faith experiences and psychological health for Caucasian lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:378–388. [Google Scholar]

- Loveland JE, Raghavan C. Near-lethal violence in a sample of high –risk men in same-sex relationships. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2014;1(1):51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow L, Klein K. Suppressor variables: The difference between ‘is’ versus ‘acting as’. Journal of Statistics Education. 2014;22:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons J, Bell T, Frechette S, Romano E. Child-to-parent violence: Frequency and family correlates. Journal of Family Violence. 2015;30(6):729–742. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza JL, Markos VH, Gonter R. A new perspective on sequential testing procedures in canonical analysis: A Monte Carlo evaluation. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1978;13:371–382. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr1303_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill GS, Wolfe VA. Battered gay men: An exploration of abuse, help-seeking, and why they stay. Journal of Homosexuality. 2000;39:1–30. doi: 10.1300/J082v39n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messinger AM. Invisible victims: Same-sex IPV in the national violence against women survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(11):2228–2243. doi: 10.1177/0886260510383023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Wagner B, Dutton MA. The relationship between battered women’s causal attributions for violence and coping efforts. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25(5):900–918. doi: 10.1177/0886260509336965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary PJ. Men who were sexually abused in childhood: Coping strategies and comparisons in psychological functioning. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37(4):710–724. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich AE, Perrin PB, Tabaac AR, Brewster ME. Coping styles and suicide in racially and ethnically diverse lesbian, bisexual, and queer women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015 doi: 10.1037/sgd0000137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Griffin MJ, Wardell JD, Ouimette P. Coping, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol involvement in trauma-exposed college students in the first three years of college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(4):1052–1064. doi: 10.1037/a0038348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Danner F, Riggle EDB. Is religiosity a protective factor against substance use in young adulthood? Only if you’re straight! Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmied EA, Padilla GA, Thomsen CJ, Lauby MDH, Harris E, Taylor MK. Sex differences in coping strategies in military survival school. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2015;29:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelau EP, Seelau SM, Poorman PB. Gender and role-based perceptions of domestic abuse: Does sexual orientation matter? Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2003;21:199–214. doi: 10.1002/bsl.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence and Victims. 2004;19(5):507–520. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.507.63686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE. Social support: A review. In: Friedman HS, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2011. pp. 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full reports of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women survey. 2010 Available at: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/183781.pdf.

- Waldrop AE, Resick PA. Coping among adult female victims of domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2004;19:291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Walters ML, Chen J, Breiding MJ. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wong JY, Fong DY, Choi AW, Tiwari A, Chan KL, Logan TK. Problem-focused coping mediates the impact of intimate partner violence on mental health among Chinese women. Psychology of Violence. 2016;6(2):313–322. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. 2013 Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85239/1/9789241564625_eng.pdf.

- Zea MC, Reisen CA, Poppen PJ. Psychological wellbeing among Latino lesbians and gay men. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 1999;5:371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Zahnd E, Grant D, Aydin M, Chia J, Padilla-Frausto I. Nearly four million California adults are victims of intimate partner violence. Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink T, Jacobson CJ, Jr, Pabst S, Regan S, Fisher BS. A lifetime of intimate partner violence: Coping strategies of older women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21(5):634–651. doi: 10.1177/0886260506286878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]