Abstract

Verapamil is a Ca2+ channel blocker and is highly prescribed as an anti-anginal, antiarrhythmic and antihypertensive drug. Ketamine, an antagonist of the Ca2+-permeable N-methyl-D-aspartate-type glutamate receptors, is a pediatric anesthetic. Previously we have shown that acetyl L-carnitine (ALCAR) reverses ketamine-induced attenuation of heart rate and neurotoxicity in zebrafish embryos. Here, we used 48 h post-fertilization zebrafish embryos that were exposed to relevant drugs for 2 or 4 h. Heart beat and overall development were monitored in vivo. In 48 h post-fertilization embryos, 2 mM ketamine reduced heart rate in a 2 or 4 h exposure and 0.5 mM ALCAR neutralized this effect. ALCAR could reverse ketamine’s effect, possibly through a compensatory mechanism involving extracellular Ca2+ entry through L-type Ca2+ channels that ALCAR is known to activate. Hence, we used verapamil to block the L-type Ca2+ channels. Verapamil was more potent in attenuating heart rate and inducing morphological defects in the embryos compared to ketamine at specific times of exposure. ALCAR reversed cardiotoxicity and developmental toxicity in the embryos exposed to verapamil or verapamil plus ketamine, even in the presence of 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoic acid 8-(diethylamino)octyl ester, an inhibitor of intracellular Ca2+ release suggesting that ALCAR acts via effectors downstream of Ca2+. In fact, ALCAR’s protective effect was blunted by oligomycin A, an inhibitor of adenosine triphosphate synthase that acts downstream of Ca2+ during adenosine triphosphate generation. We have identified, for the first time, using in vivo studies, a downstream effector of ALCAR that is critical in abrogating ketamine- and verapamil-induced developmental toxicities. Published 2016. This article is a U.S. Government work and is in the public domain in the USA.

Keywords: verapamil, heart rate, ketamine, zebrafish, acetyl L-carnitine, developmental toxicity

Introduction

Verapamil belongs to the phenylalkylamine class of L-type Ca2+ channel blockers and is used to treat cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension and angina (Prisant, 2001). Overdoses of Ca2+ channel blockers cause rapid development of hypotension, bradydysrhythmia and cardiac arrest (Derlet and Horowitz, 1995). Ketamine, a pediatric anesthetic, is an antagonist of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-type glutamate receptors (Kohrs and Durieux, 1998). Ketamine is listed as a schedule III controlled substance in the USA, due to its potential for abuse (Morgan et al., 2010; Rowland, 2005). A number of studies on rodents and non-human primates have shown that treatment with high doses of ketamine or exposure for long durations during susceptible periods of development (the brain growth spurt) can induce abnormally high levels of neuroapoptosis (Haberny et al., 2002; Ikonomidou et al., 1999; Lahti et al., 2001; Larsen et al., 1998; Malhotra et al., 1997; Maxwell et al., 2006; Slikker et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2006). Studies in humans and animals have shown that ketamine has a direct negative (Aya et al., 1997; Graf et al., 1995; Hara et al., 1994; Yeh et al., 1994) or an indirect positive (Cook et al., 1991; Endou et al., 1992; Riou et al., 1990) inotropic effect on myocardial contractility. Ketamine reduces heart rate in rats (Zausig et al., 2009) and guinea pigs (Kim et al., 2006) and acts as a cardiac depressant in dogs after pharmacological blockade of the autonomic nervous system (Pagel et al., 1992). In rhesus monkeys, extended intravenous infusions of ketamine result in decreased heart rates in pregnant females and in postnatal day 5 and 35 infants (Hotchkiss et al., 2007). However, the mechanism of how ketamine impacts cardiac function is not clear.

Several drugs that either directly or indirectly inhibit mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation (e.g., etomoxir, oxfenicine, dichloroacetate, trimetazidine, ranolazine, pyruvate, malonyl-coenzyme A decarboxylase inhibitors), improve cardiac function in experimental models and humans with cardiac ischemia and failure (Lopaschuk, 2002; Stanley, 2005). Acetyl L-carnitine (ALCAR) is an L-lysine derivative and its main role lies in the transport of long chain fatty acids into mitochondria to enter the β-oxidation cycle (Bohles et al., 1994). ALCAR preserves the mechanical function of ischemic swine hearts perfused in the presence of free fatty acids (Liedtke and Nellis, 1979). Moreover, ALCAR has been shown to ameliorate ketamine-induced behavioral alterations and body weight deficits in rats (Boctor et al., 2008), in addition to having neuroprotective effects in mammals (Zou et al., 2008), and both neuroprotective and cardioprotective effects in zebrafish (Cuevas et al., 2013; Kanungo et al., 2012).

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryo has become an important experimental model for studying various diseases, protein functions, drug toxicity and various physiological responses (Kanungo et al., 2014; Vogel, 2000). Accordingly, the therapeutic and toxic responses for both cardiac and non-cardiac drugs can be assessed by simply immersing the embryos in the water with the test drug (Kanungo et al., 2012; Langheinrich et al., 2003; Milan et al., 2003). We have previously shown that consistent with its effects on mammals (Hotchkiss et al., 2007; Irifune et al., 1991, 1997; Kim et al., 2006; Zausig et al., 2009), in zebrafish embryos, ketamine modulates the serotonergic and dopamine systems (Robinson et al., 2015, 2016) and heart rate (Kanungo et al., 2012). Based on reported observations that verapamil affects cardiac function in mammals including humans (Derlet and Horowitz, 1995; Prisant, 2001), the goal of this study was to test whether verapamil has similar effects and ketamine accentuates verapamil’s effects in zebrafish, an emerging alternate vertebrate animal model for drug screening and drug safety assessments. Here, we have undertaken in vivo mechanistic studies to demonstrate how ALCAR reverses ketamine- and verapamil-induced cardiac and developmental toxicities.

Materials and methods

Animals (zebrafish)

Adult wild-type zebrafish (D. rerio, AB strain) were obtained from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (www.zirc.org) (Eugene, OR, USA). The fish were kept in fish tanks (Aquatic Habitats, FL, USA) at the NCTR/FDA zebrafish facility containing buffered water (pH 7.5) at 28 °C, and were fed daily live brine shrimp and Zeigler dried flake food (Zeiglers, Gardeners, PA, USA). Each 3 liter tank housed eight adult males or eight females. Handling and maintenance of zebrafish complied with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the NCTR/FDA IACUC. The day–night cycle was maintained at 14: 10 h. For in-system breeding, crosses of males and females were set up the previous day with partitions that were taken off the following morning at the time of light onset at 07.30 h to stimulate spawning and fertilization. Fertilized zebrafish eggs were collected from the bottom of the tank as soon as they were laid. The eggs were placed in Petri dishes and washed thoroughly with buffered egg water (reverse osmosis water containing 60 mg sea salt [Crystal Sea®; Aquatic Eco-systems, Inc., Apopka, FL, USA] per liter of water [pH 7.5]) and then allowed to develop in an incubator at 28.5 °C for later use.

Reagents

Ketamine hydrochloride was purchased from Vedco, Inc. (St. Joseph, MO, USA). ALCAR, oligomycin A (oligomycin) and TMB-8 (3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoic acid 8-(diethylamino)octyl ester) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Verapamil hydrochloride was purchased from TOCRIS Biosciences (Ellisville, MO, USA). All other reagents including dinitrophenol used in this study were purchased from Sigma unless mentioned otherwise. Verapamil (0.05 M) and ALCAR stock (1 M) solutions were made fresh with buffered egg water. Stocks of oligomycin A (10 mM), TMB-8 (0.5 M) and dinitrophenol (1 M) were prepared using dimethyl sulfoxide as the solvent.

Treatment of zebrafish embryos with verapamil, ketamine, acetyl L-carnitine and 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoic acid 8-(diethylamino)octyl ester

For treatment with verapamil, ketamine, ALCAR, TMB-8 and oligomycin A, 48 h post-fertilization (hpf) manually dechorionated embryos were used. For every experiment, in each treatment, 10 embryos were placed in the six-well plates (Nunc non-treated plates) with 5 ml buffered egg water. Ketamine (2.0 mM), verapamil (10 μM–1 mM), ALCAR (0.5 mM), TMB-8 (0.25–0.5 mM) and oligomycin A (0.25–5.0 μM) treatments, alone or in combination continued for 2 or 4 h (static exposures). Control groups treated with equivalent amount of vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide) were examined in parallel. As we previously reported, ALCAR at 0.5 mM did not have any effect on heart rate at 2 and 4 h of exposure. In the earlier report we also showed that 0.1 mM ALCAR did not affect the ketamine-induced decrease in heart rate, doses of 0.5 and 1.0 mM ALCAR were equally effective in completely inhibiting that effect (Kanungo et al., 2012). Based on these data we chose to use 0.5 mM ALCAR for all our experiments in the present study. For the ketamine dose, we have earlier determined that 2 mM ketamine exposure results in an internal exposure of the anesthetic level of plasma concentrations in humans (Robinson et al., 2015; Trickler et al., 2014). For co-exposure to various drug combinations, the drugs were added together at the same time. For acute toxicity assessments, drug exposure continued for 2 or 4 h.

Embryo imaging, scoring heart rate and measurement of the pericardial sac area

Live images of the embryos in the six-well plates were acquired using an Olympus SZX 16 binocular microscope and DP72 camera and heart rate of each embryo was measured by visually counting ventricular beats per minute on the live video using a timer (stop watch). The data are presented by converting heart beats per minute to percentage of control (100%). Data for each group (n = 10) were used to calculate the mean and standard deviation (SD). The extent of pericardial edema in the embryos was determined by quantitation of the pericardial sac area (Carney et al., 2004). The pericardial sac area was outlined in lateral view images of the embryos and the area was quantitated using the DP2 BSW microscope digital camera software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The statistical significance of the effects of the various treatments on heart rate and pericardial edema was determined by one-way ANOVA (Sigma Stat) using Holm–Sidak pairwise multiple comparison post-hoc analysis.

Results

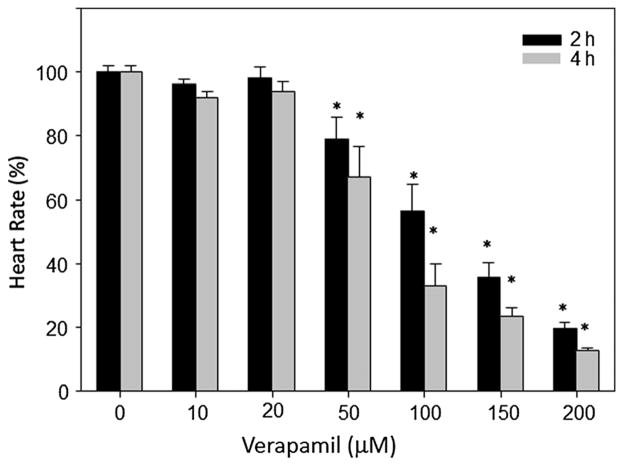

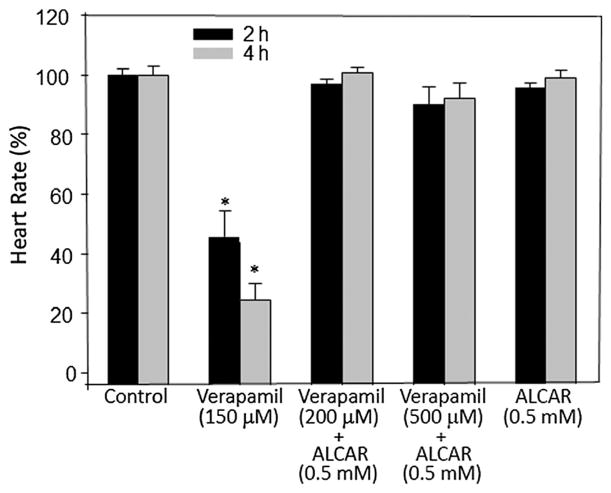

To assess the effects of verapamil on heart rate, we used zebrafish embryos at 48 hpf (Fig. 1). In these embryos, treatment with various doses of verapamil altered heart rate dose-dependently in 2 and 4 h post-treatment (Fig. 1). Doses up to 20 μM did not have any significant effect, whereas doses 50 μM and above significantly reduced heart rate. Ketamine decreases Ca2+ release from intracellular stores of rat ventricular myocytes (Kanaya et al., 1998) and its cardiac depressive effects could be caused by interference with Ca2+ influx (Endou et al., 1992; Kunst et al., 1999). L-carnitine, a naturally occurring amino acid that induces fatty acid oxidation, neutralizes ketamine-induced toxicities, such as neuronal apoptosis in the developing rat frontal cortex (Zou et al., 2008). In our previous studies, we had shown that ALCAR counteracted ketamine-induced attenuation of heart rate, implying that ALCAR potentially acted to restore the intracellular Ca2+ levels that could have been reduced due to NMDA receptor blockade by ketamine. Here, we hypothesized that were it a plausible scenario, ALCAR would also counteract verapamil (an L-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor)-induced cardiotoxicity. We chose to use a verapamil dose, 150 μM, which could cause ~50% reduction in heart rate in 2 h of exposure. At this dose, as expected, verapamil reduced heart rate at 2 and 4 h (Fig. 2). ALCAR reversed the effects of not only 150 μM verapamil but also of a higher dose of verapamil (500 μM) (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Effect of verapamil on heart rate in zebrafish embryos. Embryos (48 hpf) were exposed to various doses of verapamil for 2 or 4 h. Each group consisted of 10 embryos and the experiment was repeated at least three times. Heart rate was measured in beats per minute and the data from all the embryos in a group were averaged and shown as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the heart rates between the control and the treated groups. Significance (*) was set at P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Effects of verapamil and ALCAR on heart rate in zebrafish embryos. Embryos (48 hpf) were exposed to various doses of verapamil alone or with 0.5 mM ALCAR. Each exposure (static exposure) group consisted of 10 embryos and the experiment was repeated at least three times. Heart rate was measured in beats per minute and the data from all the embryos in a group were averaged and shown as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the heart rates between the control and the treated groups. Significance (*) was set at P < 0.05. Heart rates are shown for 2 and 4 h exposures. ALCAR, acetyl L-carnitine.

It has been reported that pretreatment of surgical patients with verapamil may reduce the dose of ketamine required for anesthesia due to increased duration of sleeping time and can potentiate the effects of some central nervous system drugs such as ketamine in mice. The latter effect has been attributed to blocked neuronal Ca2+ channels although ketamine does not interact with verapamil binding site on the L-type Ca2+ channels. We tested whether zebrafish embryos also reproduce similar effects observed in mammals. In our experiments, we used an anesthetic dose of ketamine (2 mM in water) and co-treated 48 hpf embryos with increasing doses of verapamil (50 μM–1.0 mM). The results showed that verapamil significantly potentiated ketamine’s effects on the attenuating heart rate (Fig. 3). These results indicated the effects of ketamine and verapamil were additive on the heart rate due to blockade of Ca2+ entry through NMDA receptors and the L-type Ca2+ channels by the drugs, respectively.

Figure 3.

Effects of verapamil and ketamine in the presence or absence of ALCAR on heart rate in zebrafish embryos. Embryos (48 hpf) were exposed to various doses of verapamil alone or with 2 mM ketamine and in the presence of 0.5 mM ALCAR. Each exposure group consisted of 10 embryos and the experiment was repeated at least three times. Heart rate, at 2 and 4 h post-exposure, was measured in beats per minute and the data from all the embryos in a group were averaged and shown as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the heart rates between the control and the treated groups. Significance (*) was set at P < 0.05. ALCAR, acetyl L-carnitine.

To examine whether in the presence of ALCAR (0.5 mM), the effects of ketamine plus verapamil on the heart rate could be completely reversed, as ALCAR could reverse the effects of ketamine and verapamil alone, we treated the embryos with all three drugs. The results showed that ALCAR indeed was effective in restoring the attenuated heart rate induced by ketamine and verapamil together to the control level (Fig. 3). These results further suggested that ALCAR could potentially induce intracellular Ca2+ release to compensate for the blockade of Ca2+ entry through the NMDA receptors and the L-type Ca2+ channels by ketamine and verapamil, respectively and thus could circumvent the drop in heart rate due to Ca2+ deprivation.

In a previous study, we showed that ketamine (2 mM with 20 h exposure) acted as a developmental toxicant in zebrafish. However, when treated for 2–4 h, ketamine’s developmental toxicity at the 2 mM dose was not apparent compared to control (Fig. 4A,B), although contrary to controls (Fig. 5A), the pericardial edema was evident in the ketamine-treated embryos (Fig. 4B). With 1 mM verapamil, a number of embryos showed specific deformities, particularly curved tails (41.2 ± 3.3%) (Fig. 4C) and severe pericardial edema (Fig. 5C) and within minutes, their hearts would stop beating, subsequently leading to death (data not shown). However, embryos treated with verapamil (0.1 or 0.2 mM) and 2 mM ketamine did not exhibit the curved tail phenotype (Fig. 4D,E) indicating that the effect was specific to the 1 mM verapamil dose. Embryos treated with 2 mM ketamine and 1 mM verapamil were more adversely affected (Figs. 4F and 5D) than those treated with 1 mM verapamil alone (Figs. 4C and 5C) and would eventually die faster than the latter (data not shown). A number of these embryos also had curved tails (41.5 ± 3.4%) (Fig. 4F) similar to the group treated with 1 mM verapamil alone (Fig. 4C). Embryos treated with 2 mM ketamine do not die even when the static exposure continues for a few days (data not shown). However, in the presence of 0.5 mM ALCAR, none of the effects of verapamil alone (Fig. 4G) or with ketamine (Figs. 4H and 5E) were observed indicating that ALCAR reversed the toxic effects of ketamine and verapamil as it did for the heart rate. The extent of the edematous pericardia is quantitatively presented showing the adverse effects of ketamine and verapamil alone and in combination (Fig. 5F).

Figure 4.

Morphology of 48 hpf zebrafish embryos treated with verapamil or ketamine or both, in the presence or absence of ALCAR for 2 h. Group pictures of embryos show control (A), and groups treated with 2 mM ketamine (B), 1 mM verapamil (C), 2 mM ketamine with 100 μM verapamil (D), 2 mM ketamine with 200 μM verapamil (E), 2 mM ketamine with 1 mM verapamil (F), 1 mM verapamil with 0.5 mM ALCAR (G) and 2 mM ketamine with 1 mM verapamil and 0.5 mM ALCAR (H). Curved tails are indicated (*). ALCAR, acetyl L-carnitine; Ket, ketamine; Ver, verapamil.

Figure 5.

Morphology showing pericardial area of 48 hpf zebrafish embryos treated with verapamil or ketamine or both in the presence or absence of ALCAR for 2 h. Control (A) and embryos treated with 2 mM ketamine (B), 1 mM verapamil (C), 2 mM ketamine with 1 mM verapamil (D) and 2 mM ketamine with 1 mM verapamil and 0.5 mM ALCAR (E). Arrows indicate the pericardium. Pericardial area is indicated by dotted lines and the pericardial area measurements are shown (F). Values are averaged and shown as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the pericardial areas between the control and the treated groups. Significance (*) was set at P < 0.05. Bar =125 μM. ALCAR, acetyl L-carnitine.

As ALCAR prevented ketamine- and verapamil-induced cardiotoxicity, we hypothesized that intracellular Ca2+ release could compensate for the lack of extracellular Ca2+ via NMDA receptors (by ketamine) and L-type Ca2+ channels (by verapamil). Therefore, we used the intracellular Ca2+ release inhibitor TMB-8 to block such a compensatory potential. TMB-8 modulates cellular Ca2+ metabolism by preventing intracellular Ca2+ mobilization via inhibition of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ release (Nishizuka, 1988). In zebrafish embryos, TMB-8 dose-dependently reduced heart rate (data not shown) and a higher dose (0.5 mM) completely caused the heart to stop beating in 2 h of co-exposure with either ketamine or verapamil alone or in combination (Fig. 6). However, in the presence of ALCAR, the adverse effect of TMB-8 was completely obliterated. These data suggested that ALCAR function is potentially carried out by an effector molecule downstream of Ca2+.

Figure 6.

TMB-8, an inhibitor of intracellular Ca2+ release does not interrupt ALCAR’s protection from ketamine- and verapamil-induced cardiotoxicity. Embryos (48 hpf) were exposed for 2 h with 1 mM verapamil alone or with 2 mM ketamine and in the presence of 0.5 mM ALCAR and TMB-8 (either 0.25 or 0.5 mM). Each exposure group consisted of 10 embryos and the experiment was repeated three times. Post-exposure, heart rate was measured in beats per minute and the data from all the embryos in a group were averaged and shown as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the heart rates between the control and the treated groups. Significance (*) was set at P < 0.05. ALCAR, acetyl L-carnitine; TMB-8, 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoic acid 8-(diethylamino)octyl ester.

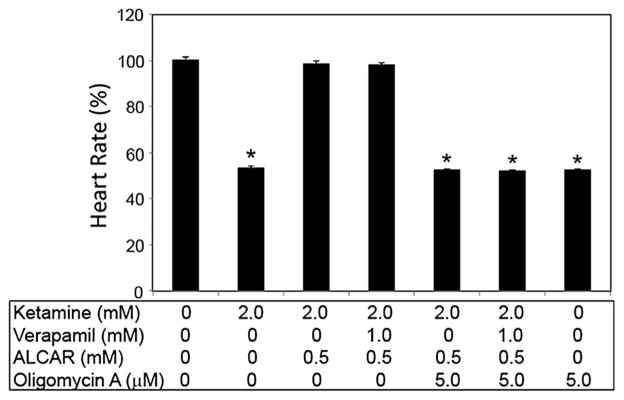

With the reversal of heart rate to control levels by ALCAR even in the presence of ketamine, verapamil and TMB-8, the latter three inhibiting intracellular Ca2+, we redirected our focus to selective targets downstream of Ca2+. One of the major downstream effectors of Ca2+ is adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthase. The addition of oligomycin A (an inhibitor of the mitochondrial F-ATP synthase) to embryos along with ALCAR, ketamine and verapamil obliterated the protective effects of ALCAR on ketamine- and verapamil-induced cardiotoxicity (Fig. 7). Doses of oligomycin less than 0.5 mM were ineffective in interfering with ALCAR’s beneficial effects (data not shown). These results indicated that ALCAR’s function is not dependent on Ca2+ but is mediated by the latter’s downstream target, ATP synthase.

Figure 7.

Oligomycin disrupts ALCAR’s protective effects on ketamine-and verapamil- induced cardiotoxicity. Embryos (48 hpf) were exposed for 2 h with 1 mM verapamil alone or with 2 mM ketamine and in the presence of 0.5 mM ALCAR, and oligomycin (5 μM). Each exposure group consisted of 10 embryos and the experiment was repeated three times. Post-exposure, heart rate was measured in beats per minute and the data from all the embryos in a group were averaged and shown as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the heart rates between the control and the treated groups. Significance (*) was set at P <0.05. ALCAR, acetyl L-carnitine.

Discussion

Our previous study has shown that ALCAR reverses ketamine-induced attenuated heart rate in zebrafish embryos and we hypothesized that ALCAR, due to its ability to upregulate L-type Ca2+ channels (Tewari et al., 1995), could compensate for ketamine-induced blockade of Ca2+-permeable NMDA receptors (Kanungo et al., 2012) (Fig. 8). It has been shown that ketamine decreases Ca2+ release from intracellular stores of rat ventricular myocytes (Kanaya et al., 1998). There are also reports that the cardiac depressive effects of ketamine could be caused by interference with Ca2+ influx (Endou et al., 1992; Kunst et al., 1999). It has also been suggested that pretreatment of surgical patients with verapamil may reduce the dose of ketamine required for anesthesia due to increased duration of sleeping time (Saha et al., 1990) and can potentiate the effects of some central nervous system drugs such as ketamine in mice (Shen and Sangiah, 1995). The latter effect has been attributed to blocked neuronal Ca2+ channels although ketamine does not interact with the verapamil binding site on the L-type Ca2+ channels (Hirota and Lambert, 1996). In the current study, we provide evidence that ALCAR can reverse verapamil-induced cardiotoxicity caused by verapamil treatment alone or with ketamine. Verapamil is an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker (Prisant, 2001), and we show that verapamil dose-dependently attenuated the heart rate in zebrafish embryos. At high dose, it induced severe developmental anomalies and cardiotoxicity. With these results, what remained unanswered however, is whether in the presence of all three compounds, verapamil, ketamine and ALCAR, normalization of overall development and heart rate occurs or not. To answer this question, we followed a completely non-invasive in vivo approach. Instead of directly monitoring Ca2+ in the heart by imaging, which would need microinjection of fluorescent Ca2+ trackers, and therefore, may interfere with survival rate and normal physiology in addition to being exposed to the drugs of interest, we chose to use various inhibitors of Ca2+ and monitored the downstream physiological effect on the heart rate. The zebrafish embryo is an intact organism in which the heart beat is observed in its native environment (water) rather than in isolation in a culture medium (Kim et al., 2006), an advantage that can be utilized to test for safety and efficacy of drugs in vivo.

Figure 8.

Schematic presentation of a potential mechanism of ALCAR’s reversal of ketamine- and verapamil-induced cardiotoxicity. NMDA receptors are Ca2+ permeable. Ketamine as an antagonist of NMDA receptors can inhibit Ca2+ entry into the cells. In the absence of intracellular Ca2+, the mitochondrial ATP synthase activity is inhibited that could result in blunted ATP generation. ALCAR potentially bypasses the need for Ca2+ to induce ATP synthase activity and instead directly induces ATP synthase activity. ALCAR, acetyl L-carnitine; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; NMDAR, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor.

The effect of ketamine, an NMDA receptor antagonist, on heart rate has been reported for a variety of mammals, such as rats (Zausig et al., 2009), rabbits (Yeh et al., 1994) and guinea pigs (Kim et al., 2006). The zebrafish embryo response to ketamine with regard to heart rate is also concordant with that of human infants (Saarenmaa et al., 2001) and non-human primate infants at postnatal days 5 and 35 (Hotchkiss et al., 2007). Zebrafish embryos can accurately model drug effects on mammals and humans (Kanungo et al., 2014), and our earlier studies have shown that in 48 hpf embryos, a 2 h exposure to ketamine was effective in significantly lowering the heart rate (Kanungo et al., 2012).

In humans, neonatal myocardium appears more dependent on the entry of extracellular Ca2+ rather than the release of Ca2+ from intracellular sarcoplasmic reticulum (Kudoh et al., 2003). Ketamine decreases Ca2+ release from intracellular stores of rat ventricular myocytes (Kanaya et al., 1998). There are also reports that the cardiac depressive effects of ketamine could be caused by interference with Ca2+ influx (Endou et al., 1992; Kunst et al., 1999). Among the compounds that appear to have a neutralizing effect on ketamine-induced toxicities, such as neuronal apoptosis in the developing rat frontal cortex, is L-carnitine (Zou et al., 2008), a naturally occurring amino acid that induces fatty acid oxidation. The mechanism underlying the effect of L-carnitine to inhibit such neurotoxicity is not clear. On the other hand, ketamine is known to induce blockade of lipid oxidation in rat heart (Ovchinnikov et al., 1989). Here, we show that ALCAR not only neutralized the ketamine-induced decrease in heart rate as we reported in our earlier study (Kanungo et al., 2012), but also reversed verapamil’s adverse effects on the heart rate in the presence or absence of ketamine, suggesting that ALCAR may have altered cellular Ca2+ transport or intracellular Ca2+ release or both. Carnitine is known to be an endogenous promoter of Ca2+ efflux from rat heart mitochondria (Baydoun et al., 1988) and acyl-carnitines increase Ca2+ concentrations in the cytoplasm of rat ventricular cardiomyocytes (Berezhnov et al., 2008). In patients with mild diastolic heart failure, ALCAR improves their symptoms (Serati et al., 2010). Differential effects of ketamine and ALCAR have been reported, which show that ketamine induces a blockade of lipid oxidation and a decrease in ATP content in rat heart, whereas ALCAR facilitates fatty acid oxidation to support ATP production (Hagen et al., 2002). Although our study shows the differential effects of ketamine (with or without verapamil) and ALCAR on the zebrafish heart rate, direct evidence on whether such counteracting effects are exclusively mediated by ATP, remains to be uncovered. Our studies showed that ALCAR completely reverses the adverse effects on heart rate (even lethality) induced by 0.5 mM dinitrophenol alone or with ketamine co-treatment (data not shown). These findings suggest that ALCAR counteracts acute cardiotoxicity in the zebrafish embryos by replenishing ATP in a way that is not dinitrophenol-sensitive. This would mean that ATP production might be sustained via beta-oxidation of fatty acids instead of the oxidative phosphorylation. ALCAR can induce fatty acid metabolism via beta-oxidation (Hagen et al., 2002).

In the current study, ALCAR also reversed the reduced heart rate induced by verapamil, an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker, in the zebrafish embryos even in the presence of ketamine, indicating that ALCAR may be regulating heart rate by modulating intracellular Ca2+ levels. In our in vivo approach to modulate the availability of cellular Ca2+ to determine how ketamine, verapamil and ALCAR modulate heart rate, we used the intracellular Ca2+ inhibitor, TMB-8. TMB-8 acts as an intracellular Ca2+ antagonist. In mammalian skeletal or smooth muscle, TMB-8, an amphiphilic ester, acts to inhibit intracellular Ca2+ availability (Chiou and Malagodi, 1975; Malagodi and Chiou, 1974a,b). TMB-8 enhanced ketamine inhibition of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate production in rat heart myocytes (Kudoh et al., 2002). Our study showed that just like verapamil, TMB-8 alone could drastically reduce heart rate followed by lethality (data not shown) and its effects were exacerbated in the presence of ketamine; however, it was ineffective in altering heart rate or overall development in the presence of ALCAR alone or in combination with ketamine and verapamil, suggesting that reversal of this acute toxicity depended on targets acting downstream of Ca2+.

It has been reported that verapamil has the potential to change myocardial Ca2+ sensitivity in zebrafish and the mechanism by which this occurs may involve myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity of the heart muscle (Haustein et al., 2015). A potential mechanism for the effects of ketamine and ALCAR on mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) linked to Ca2+ in zebrafish was discussed in our previous study (Kanungo et al., 2012). Involvement of MAPK/ERK pathway in ketamine-induced neurotoxicity in mice has been reported (Straiko et al., 2009). However, a distinct effector molecule downstream of the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway, has not been identified that can explain ketamine-induced toxicity, in which case intervention at the MAPK/ERK level might prove deleterious as this signaling pathway is ubiquitous and critical for overall cellular physiology.

We were focused on identifying the effector(s) downstream of Ca2+ signaling that could be activated by ALCAR. In muscle-derived cell cultures from patients with collagen type VI myopathies, addition of oligomycin results in mitochondrial depolarization (Angelin et al., 2007). In the present investigation, we show that oligomycin blunted ALCAR’s beneficial effects on toxicities induced by either ketamine or verapamil or TMB-8 alone or all in combination. Oligomycin A, an inhibitor of the mitochondrial F-ATP synthase, blocks ATP synthesis in the mitochondria. Our results thus point to a direct role of ALCAR-mediated ATP synthase activity in protecting zebrafish embryos from toxicities induced by ketamine, verapamil and TMB-8, alone or in combination (Fig. 8). Our future studies would focus on how ALCAR affects ATP synthase activity, whether at the transcriptional or post-translational levels or by upregulating the expression of any inhibitor(s) of ATPase. Nonetheless, for the first time, we have identified a molecule that is responsible for imparting ALCAR’s protective effects on ketamine- and verapamil-induced toxicities. These results provide mechanistic data with an insight on how these drugs might work in humans and how their reported toxicities could be ameliorated with potential intervention.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors did not report any conflict of interest.

References

- Angelin A, Tiepolo T, Sabatelli P, Grumati P, Bergamin N, Golfieri C, Mattioli E, Gualandi F, Ferlini A, Merlini L, Maraldi NM, Bonaldo P, Bernardi P. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy and prospective therapy with cyclosporins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:991–996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610270104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aya AG, Robert E, Bruelle P, Lefrant JY, Juan JM, Peray P, Eledjam JJ, de La Coussaye JE. Effects of ketamine on ventricular conduction, refractoriness, and wavelength: potential antiarrhythmic effects: a high-resolution epicardial mapping in rabbit hearts. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1417–1427. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199712000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydoun AR, Markham A, Morgan RM, Sweetman AJ. Palmitoyl carnitine: an endogenous promotor of calcium efflux from rat heart mitochondria. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:3103–3107. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezhnov AV, Fedotova EI, Nenov MN, Kokoz Iu M, Zinchenko VP, Dynnik VV. Destabilization of the cytosolic calcium level and cardiomyocyte death in the presence of long-chain fatty acid derivatives. Biofizika. 2008;53:1025–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boctor SY, Wang C, Ferguson SA. Neonatal PCP is more potent than ketamine at modifying preweaning behaviors of Sprague–Dawley rats. Toxicol Sci. 2008;106:172–179. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohles H, Evangeliou A, Bervoets K, Eckert I, Sewell A. Carnitine esters in metabolic disease. Eur J Pediatr. 1994;153:S57–S61. doi: 10.1007/BF02138779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney SA, Peterson RE, Heideman W. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor/aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator pathway causes developmental toxicity through a CYP1A-independent mechanism in zebrafish. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:512–521. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.3.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou CY, Malagodi MH. Studies on the mechanism of action of a new Ca2+ antagonist, 8-(N,N-diethylamino)octyl 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoate hydrochloride in smooth and skeletal muscles. Br J Pharmacol. 1975;53:279–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1975.tb07359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DJ, Carton EG, Housmans PR. Mechanism of the positive inotropic effect of ketamine in isolated ferret ventricular papillary muscle. Anesthesiology. 1991;74:880–888. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199105000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas E, Trickler WJ, Guo X, Ali SF, Paule MG, Kanungo J. Acetyl L-carnitine protects motor neurons and Rohon-Beard sensory neurons against ketamine-induced neurotoxicity in zebrafish embryos. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2013;39:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derlet RW, Horowitz BZ. Cardiotoxic drugs. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1995;13:771–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endou M, Hattori Y, Nakaya H, Gotoh Y, Kanno M. Electrophysiologic mechanisms responsible for inotropic responses to ketamine in guinea pig and rat myocardium. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:409–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf BM, Vicenzi MN, Martin E, Bosnjak ZJ, Stowe DF. Ketamine has stereospecific effects in the isolated perfused guinea pig heart. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:1426–1437. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199506000-00014. discussion 1425A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberny KA, Paule MG, Scallet AC, Sistare FD, Lester DS, Hanig JP, Slikker W., Jr Ontogeny of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor system and susceptibility to neurotoxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2002;68:9–17. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/68.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen TM, Moreau R, Suh JH, Visioli F. Mitochondrial decay in the aging rat heart: evidence for improvement by dietary supplementation with acetyl-L-carnitine and/or lipoic acid. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;959:491–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y, Tamagawa M, Nakaya H. The effects of ketamine on conduction velocity and maximum rate of rise of action potential upstroke in guinea pig papillary muscles: comparison with quinidine. Anesth Analg. 1994;79:687–693. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199410000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haustein M, Hannes T, Trieschmann J, Verhaegh R, Koster A, Hescheler J, Brockmeier K, Adelmann R, Khalil M. Excitation-contraction coupling in zebrafish ventricular myocardium is regulated by trans-sarcolemmal Ca2+ influx and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release. PLoS One. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125654. doi:10.e0125654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota K, Lambert DG. I.v. anaesthetic agents do not interact with the verapamil binding site on L-type voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:385–386. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss CE, Wang C, Slikker W., Jr Effect of prolonged ketamine exposure on cardiovascular physiology in pregnant and infant rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2007;46:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidou C, Bosch F, Miksa M, Bittigau P, Vockler J, Dikranian K, Tenkova TI, Stefovska V, Turski L, Olney JW. Blockade of NMDA receptors and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Science. 1999;283:70–74. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irifune M, Shimizu T, Nomoto M. Ketamine-induced hyperlocomotion associated with alteration of presynaptic components of dopamine neurons in the nucleus accumbens of mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;40:399–407. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90571-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irifune M, Fukuda T, Nomoto M, Sato T, Kamata Y, Nishikawa T, Mietani W, Yokoyama K, Sugiyama K, Kawahara M. Effects of ketamine on dopamine metabolism during anesthesia in discrete brain regions in mice: comparison with the effects during the recovery and subanesthetic phases. Brain Res. 1997;763:281–284. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaya N, Murray PA, Damron DS. Propofol and ketamine only inhibit intracellular Ca2+ transients and contraction in rat ventricular myocytes at supraclinical concentrations. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:781–791. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199803000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanungo J, Cuevas E, Ali SF, Paule MG. L-Carnitine rescues ketamine-induced attenuated heart rate and MAPK (ERK) activity in zebrafish embryos. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;33:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanungo J, Cuevas E, Ali SF, Paule MG. Zebrafish model in drug safety assessment. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:5416–5429. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666140205145658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Kang HS, Lee MY, Lee SJ, Seol JW, Park SY, Kim IS, Kim NS, Kim SZ, Kwak YG, Kim JS. Ketamine-induced cardiac depression is associated with increase in [Mg2+]i and activation of p38 MAP kinase and ERK 1/2 in guinea pig. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:716–722. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrs R, Durieux ME. Ketamine: teaching an old drug new tricks. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:1186–1193. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199811000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudoh A, Kudoh E, Katagai H, Takazawa T. Ketamine suppresses norepinephrine-induced inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate formation via pathways involving protein kinase C. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:552–557. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200203000-00013. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudoh A, Kudoh E, Katagai H, Takazawa T. Norepinephrine-induced inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate formation in atrial myocytes is regulated by extracellular calcium, protein kinase C, and calmodulin. Jpn Heart J. 2003;44:547–556. doi: 10.1536/jhj.44.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst G, Martin E, Graf BM, Hagl S, Vahl CF. Actions of ketamine and its isomers on contractility and calcium transients in human myocardium. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1363–1371. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199905000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, Parwani A, Tamminga CA. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:455–467. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langheinrich U, Vacun G, Wagner T. Zebrafish embryos express an orthologue of HERG and are sensitive toward a range of QT-prolonging drugs inducing severe arrhythmia. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;193:370–382. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen B, Hoff G, Wilhelm W, Buchinger H, Wanner GA, Bauer M. Effect of intravenous anesthetics on spontaneous and endotoxin-stimulated cytokine response in cultured human whole blood. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1218–1227. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199811000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke AJ, Nellis SH. Effects of carnitine in ischemic and fatty acid supplemented swine hearts. J Clin Invest. 1979;64:440–447. doi: 10.1172/JCI109481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopaschuk GD. Metabolic abnormalities in the diabetic heart. Heart Fail Rev. 2002;7:149–159. doi: 10.1023/a:1015328625394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malagodi MH, Chiou CY. Pharmacological evaluation of a new Ca2+ antagonist, 8-(N,N-diethylamino)-octyl-3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoate hydrochloride (TMB-8): studies in smooth muscles. Eur J Pharmacol. 1974a;27:25–33. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(74)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malagodi MH, Chiou CY. Pharmacological evaluation of a new Ca++ antagonist, 8-(N,N-diethylamino)octyl 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoate hydrochloride (TMB-8): studies in skeletal muscles. Pharmacology. 1974b;12:20–31. doi: 10.1159/000136517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra AK, Pinals DA, Adler CM, Elman I, Clifton A, Pickar D, Breier A. Ketamine-induced exacerbation of psychotic symptoms and cognitive impairment in neuroleptic-free schizophrenics. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;17:141–150. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell CR, Ehrlichman RS, Liang Y, Trief D, Kanes SJ, Karp J, Siegel SJ. Ketamine produces lasting disruptions in encoding of sensory stimuli. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:315–324. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan DJ, Peterson TA, Ruskin JN, Peterson RT, MacRae CA. Drugs that induce repolarization abnormalities cause bradycardia in zebrafish. Circulation. 2003;107:1355–1358. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061912.88753.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CJ, Muetzelfeldt L, Curran HV. Consequences of chronic ketamine self-administration upon neurocognitive function and psychological wellbeing: a 1-year longitudinal study. Addiction. 2010;105:121–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. The molecular heterogeneity of protein kinase C and its implications for cellular regulation. Nature. 1988;334:661–665. doi: 10.1038/334661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovchinnikov IV, Gimmel’farb GN, Abidova SS. The action of anaprilin and ketamine on fatty acid metabolism in the myocardium. Farmakol Toksikol. 1989;52:37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagel PS, Kampine JP, Schmeling WT, Warltier DC. Ketamine depresses myocardial contractility as evaluated by the preload recruitable stroke work relationship in chronically instrumented dogs with autonomic nervous system blockade. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:564–572. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199204000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prisant LM. Verapamil revisited: a transition in novel drug delivery systems and outcomes. Heart Dis. 2001;3:55–62. doi: 10.1097/00132580-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou B, Viars P, Lecarpentier Y. Effects of ketamine on the cardiac papillary muscle of normal hamsters and those with cardiomyopathy. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:910–918. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199011000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BL, Dumas M, Paule MG, Ali SF, Kanungo J. Opposing effects of ketamine and acetyl L-carnitine on the serotonergic system of zebrafish. Neurosci Lett. 2015;607:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BL, Dumas M, Cuevas E, Gu Q, Paule MG, Ali SF, Kanungo J. Distinct effects of ketamine and acetyl l-carnitine on the dopamine system in zebrafish. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2016;54:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland LM. Subanesthetic ketamine: how it alters physiology and behavior in humans. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2005;76:C52–C58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarenmaa E, Neuvonen PJ, Huttunen P, Fellman V. Ketamine for procedural pain relief in newborn infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;85:F53–F56. doi: 10.1136/fn.85.1.F53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha N, Chugh Y, Sankaranarayanan A, Datta H. Interactions of verapamil and diltiazem with ketamine: effects on memory and sleeping time in mice. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1990;12:507–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serati AR, Motamedi MR, Emami S, Varedi P, Movahed MR. L-carnitine treatment in patients with mild diastolic heart failure is associated with improvement in diastolic function and symptoms. Cardiology. 2010;116:178–182. doi: 10.1159/000318810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Sangiah S. Effects of cadmium and verapamil on ketamine-induced anesthesia in mice. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1995;37:201–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slikker W, Jr, Paule MG, Wright LK, Patterson TA, Wang C. Systems biology approaches for toxicology. J Appl Toxicol. 2007;27:201–217. doi: 10.1002/jat.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley WC. Rationale for a metabolic approach in diabetic coronary patients. Coron Artery Dis. 2005;16(Suppl 1):S11–S15. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200511001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straiko MM, Young C, Cattano D, Creeley CE, Wang H, Smith DJ, Johnson SA, Li ES, Olney JW. Lithium protects against anesthesia-induced developmental neuroapoptosis. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:862–868. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819b5eab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari K, Simard JM, Peng YB, Werrbach-Perez K, Perez-Polo JR. Acetyl-L-carnitine arginyl amide (ST857) increases calcium channel density in rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells. J Neurosci Res. 1995;40:371–378. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490400311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickler WJ, Guo X, Cuevas E, Ali SF, Paule MG, Kanungo J. Ketamine attenuates cytochrome p450 aromatase gene expression and estradiol-17beta levels in zebrafish early life stages. J Appl Toxicol. 2014;34:480–488. doi: 10.1002/jat.2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel G. Zebrafish earns its stripes in genetic screens. Science. 2000;288:1160–1161. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JH, Fu Y, Wilson FA, Ma YY. Ketamine affects memory consolidation: differential effects in T-maze and passive avoidance paradigms in mice. Neuroscience. 2006;140:993–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh FC, Tzeng CC, Chang CL, Chen HI. The direct cardiac effects of ketamine studied on the intact isolated rabbit heart. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 1994;32:209–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zausig YA, Busse H, Lunz D, Sinner B, Zink W, Graf BM. Cardiac effects of induction agents in the septic rat heart. Crit Care. 2009;13:R144. doi: 10.1186/cc8038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X, Sadovova N, Patterson TA, Divine RL, Hotchkiss CE, Ali SF, Hanig JP, Paule MG, Slikker W, Jr, Wang C. The effects of L-carnitine on the combination of, inhalation anesthetic-induced developmental, neuronal apoptosis in the rat frontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2008;151:1053–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]