Abstract

Background

It is still unclear whether low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) affects cardiovascular outcomes after acute myocardial infarction (AMI), especially in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Methods

A total of 984 AMI patients with diabetes mellitus from the DIabetic Acute Myocardial InfarctiON Disease (DIAMOND) Korean multicenter registry were divided into two groups based on HDL-C level on admission: normal HDL-C group (HDL-C ≥ 40 mg/dL, n = 519) and low HDL-C group (HDL-C < 40 mg/dL, n = 465). The primary endpoint was 2-year major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as a composite of cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), and target vessel revascularization (TVR).

Results

The median follow-up duration was 730 days. The 2-year MACE rates were significantly higher in the low HDL-C group than in the normal HDL-C group (MACE, 7.44% vs. 3.49%, p = 0.006; cardiac death, 3.72% vs. 0.97%, p = 0.004; non-fatal MI, 1.75% vs. 1.55%, p = 0.806; TVR, 3.50% vs. 0.97%, p = 0.007). Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that the low HDL-C group had a significantly higher incidence of MACE compared to the normal HDL-C group (log-rank p = 0.013). After adjusting for conventional risk factors, Cox proportional hazards analysis suggested that low HDL-C was an independent risk predictor for MACE (hazard ratio [HR] 3.075, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.034-9.144, p = 0.043).

Conclusions

In patients with diabetes mellitus, low HDL-C remained an independent risk predictor for MACE after adjusting for multiple risk factors during 2-year follow-up of AMI.

Trial registration

This study was the sub-analysis of the prospective multi-center registry of DIAMOND (Diabetic acute myocardial infarction Disease) in Korea. This is the observational study supported by Bayer HealthCare, Korea. Study number is 15614. First patient first visit was 02 April 2010 and last patient last visit was 09 December 2013.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12944-016-0374-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Major adverse cardiovascular events, Acute myocardial infarction, Diabetes mellitus

Background

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a leading cause of mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus. Recent data revealed a 10–15% 1-year mortality rate after AMI in a diabetic population [1]. Korean data also showed a higher mortality rate after AMI in diabetic patients compared to non-diabetic patients [2]. Preventive strategies targeting platelet activity and lipid profiles in addition to glycemic control and lifestyle modification are an essential part of management in these patients [3, 4].

Previous primary prevention trials revealed that low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) level is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular events in the general population [5, 6]. The Treating to New Targets (TNT) study revealed that approximately 15% of patients with diabetes mellitus have low HDL-C level [7]. In diabetes, insulin resistance increases triglyceride-enriched HDL particles and causes more rapid clearance of HDL particles [8]. Thus, low HDL-C is more common in diabetic patients. Moreover, previous epidemiologic studies demonstrated a higher prevalence of low HDL-C in the Asian population [9, 10]. The association between low HDL-C and coronary heart disease seemed to be stronger in the Asian population compared to non-Asians [11].

Recently, low HDL-C levels have been reportedly associated with a higher rate of cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary artery disease, percutaneous coronary intervention, or even AMI [12–14]. However, it is still controversial whether low HDL-C affects cardiovascular outcomes after AMI. In addition, no studies have evaluated AMI patients with diabetes mellitus. In the present study, we have investigated the prevalence of low HDL-C and its long-term clinical impact in diabetic patients after AMI.

Methods

Study design

The DIAMOND (DIabetic Acute Myocardial infarctiON Disease registry in Korea) study was a multicenter, prospective observational study [15]. Briefly, between April 2010 and December 2013, 1,198 diabetic patients admitted for AMI were enrolled at 22 institutions in South Korea. The study participants were encouraged to follow up at 1, 6, 12, and 24 months after discharge. The study was approved by the institutional review board of each institute and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

The present study was a retrospective analysis of previously collected data that were locked at December 2014. During the follow-up period, 6 patients withdrew consent, 79 never followed up after discharge, and 129 had missing values for laboratory findings on admission. Finally, 984 patients were analyzed.

Definitions

AMI was defined based on elevated cardiac troponin-I or T level (exceeding upper limit of normal) or creatine kinase-MB fraction (CK-MB) (exceeding three times upper limit of normal), along with angiographic evidence. Angiographic evidence for AMI included significant coronary stenosis, i.e., more than 50% luminal stenosis, intracoronary filling defect or haziness suggesting coronary thrombus/vulnerable plaque, or coronary artery vasospasm confirmed by intracoronary acetylcholine or ergonovine provocation test. Diabetes mellitus was defined by fasting plasma glucose level on two separate occasions ≥ 126 mg/dL, a random plasma glucose level ≥ 200 mg/dL, 2-h plasma glucose post-75 g dextrose load on two separate occasions ≥ 200 mg/dL, or taking oral hypoglycemic agents or using insulin. Dyslipidemia was defined as total cholesterol level ≥ 240 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level ≥ 130 mg/dL, HDL-C level < 40 mg/dL, triglyceride level ≥ 150 mg/dL, and/or treatment with lipid lowering agents. Low HDL-C was defined as < 40 mg/dL. Renal function was estimated with the glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), which was calculated with the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation as following: eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) = 175 × (serum creatinine level)-1.154 × (age)-0.203 × (0.742 if female) [16].

Endpoint

In the present analysis, major adverse cardiac events (MACE) was defined as a composite of cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), and target vessel revascularization (TVR). Revascularization other than TVR (non-TVR) was also analyzed. Definite stent thrombosis was assessed according to the Academic Research Consortium definition.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were reported as count (percentage) and continuous variables as the mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons between two groups were performed using the independent Student’s t-test for continuous variables, and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Kaplan–Meier survival curves with a log-rank test and Cox proportional hazard model analyses were performed to compare the long-term incidence of MACE and cardiac death between the two groups. The univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were used to identify risk predictors for MACE and cardiac death. The risk factors were tested with the multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model by the backward selection method. The candidate variables for the model included HDL-C level, age, men, body mass index (BMI), current smoking, previous MI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) on admission, primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), hypertension, statin use, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) level, LDL-C level, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), multivessel disease, lesion type (B2/C), stent diameter ≤ 2.75 mm, and stent length ≥ 28 mm. The selection significance level was 0.1. The results were expressed as the hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value. All tests were two-tailed, and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (v. 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., USA).

Results

Among a total of 984 diabetic patients who experienced AMI, 465 patients (47.3%) were in the low HDL-C group. Baseline clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The low HDL-C group had more men (p = 0.002). There were fewer patients with newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus in the low HDL-C group (p = 0.034). Laboratory findings showed lower total cholesterol and higher triglyceride levels in the low HDL-C group (p < .001). Angiographic findings showed no significant difference between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics

| Low HDL (n = 465) | Normal HDL (n = 519) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.12 ± 9.91 | 65.10 ± 9.78 | 0.120 |

| Male, n (%) | 328 (70.54) | 318 (61.27) | 0.002 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.23 ± 3.01 | 24.06 ± 3.02 | 0.301 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 164 (35.42) | 166 (31.98) | 0.255 |

| Newly diagnosed DM, n (%) | 30 (6.45) | 53 (10.21) | 0.034 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 302 (65.09) | 335 (64.92) | 0.957 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 115 (24.78) | 149 (28.76) | 0.160 |

| Previous MI, n (%) | 28 (6.02) | 33 (6.36) | 0.827 |

| On Admission | |||

| STEMI, n (%) | 217 (46.67) | 254 (48.94) | 0.476 |

| Primary PCI, n (%) | 280 (60.22) | 318 (61.27) | 0.735 |

| LVEF, n (%) | 50.51 ± 12.31 | 51.00 ± 11.26 | 0.522 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 162.92 ± 45.74 | 180.83 ± 44.34 | <.001 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 151.59 ± 109.69 | 121.63 ± 83.35 | <.001 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 100.97 ± 34.76 | 105.63 ± 45.82 | 0.072 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 32.70 ± 5.22 | 53.8 ± 26.83 | <.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.16 ± 16.55 | 1.69 ± 11.84 | 0.611 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.83 ± 1.58 | 7.66 ± 1.49 | 0.111 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 6.00 ± 15.69 | 6.01 ± 24.07 | 0.993 |

| Peak CK-MB (ng/mL) | 75.71 ± 120.75 | 85.67 ± 122.03 | 0.202 |

| Maximum Troponin-I (ng/mL) | 28.76 ± 55.53 | 29.71 ± 58.47 | 0.825 |

| Medication at discharge | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 449 (98.25) | 510 (98.84) | 0.442 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 434 (94.97) | 487 (94.38) | 0.684 |

| Cilostazol, n (%) | 88 (19.26) | 105 (20.35) | 0.670 |

| Beta blocker, n (%) | 394 (85.65) | 437 (84.36) | 0.573 |

| ACEI/ARB, n (%) | 376 (81.74) | 441 (85.14) | 0.153 |

| Statin, n (%) | 381 (82.83) | 452 (87.26) | 0.052 |

| Nitrate, n (%) | 128 (27.83) | 149 (28.76) | 0.745 |

| Insulin, n (%) | 76 (16.52) | 70 (13.51) | 0.188 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and numbers (%) for categorical variables. BMI body mass index, DM diabetes mellitus, MI myocardial infarction, STEMI ST-segment elevation MI, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, hsCRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, CK-MB creatine kinase-MB, ACEI angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB angiotensin II receptor blocker

Table 2.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics

| Low HDL | Normal HDL | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target vessel, n (%) | |||

| Left main | 14 (3.01) | 11 (2.12) | 0.375 |

| LAD | 224 (48.17) | 270 (52.02) | 0.228 |

| LCX | 114 (24.52) | 144 (27.75) | 0.250 |

| RCA | 175 (37.63) | 178 (34.30) | 0.276 |

| Multivessel disease, n (%) | 284 (61.08) | 302 (58.19) | 0.357 |

| Type B2/C lesion, n (%) | 371 (84.9) | 403 (80.76) | 0.095 |

| TIMI grade, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 187 (42.79) | 190 (38.08) | 0.404 |

| 1 | 52 (11.90) | 64 (12.83) | |

| 2 | 46 (10.53) | 78 (15.63) | |

| 3 | 152 (34.78) | 167 (33.47) | |

| Drug-eluting stent, n (%) | 398 (98.76) | 445 (97.8) | 0.294 |

| Stent diameter (mm) | 3.10 ± 0.45 | 3.13 ± 0.44 | 0.215 |

| Stent length (mm) | 25.44 ± 8.25 | 24.71 ± 9.12 | 0.272 |

| Stent number | 1.57 ± 0.89 | 1.55 ± 0.82 | 0.722 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and numbers (%) for categorical variables. LAD left anterior descending artery, LCX left circumflex artery, RCA right coronary artery

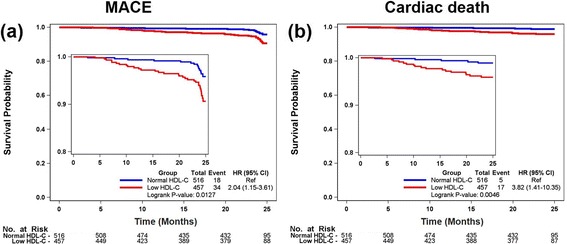

In-hospital and 2-year clinical outcomes are shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences in in-hospital deaths and complications between the two groups. The 2-year clinical outcomes were accessed in the remaining 973 patients after excluding the patients with in-hospital death. Median follow-up period was 730 days. During the follow-up period, the incidence of MACE, cardiac death, and TVR was significantly higher in the low HDL-C group (MACE, 7.44% vs. 3.49%, p = 0.006; cardiac death, 3.72% vs. 0.97%, p = 0.004; non-fatal MI, 1.75% vs. 1.55%, p = 0.806; TVR, 3.50% vs. 0.97%, p = 0.007). Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that the low HDL-C group had a significantly higher incidence of MACE and cardiac death compared to the normal HDL-C group (MACE, log-rank p = 0.012; cardiac death, log-rank p = 0.005; Fig. 1).

Table 3.

In-hospital and 2-year clinical outcomes after acute myocardial infarction

| Low HDL | Normal HDL | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital | |||

| Death | 8 (1.72) | 3 (0.58) | 0.089 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 10 (2.15) | 6 (1.16) | 0.218 |

| Acute renal failure | 5 (1.08) | 2 (0.39) | 0.199 |

| Major bleeding | 4 (0.86) | 6 (1.16) | 0.644 |

| During follow-up period | |||

| MACE | 34 (7.44) | 18 (3.49) | 0.006 |

| Cardiac death | 17 (3.72) | 5 (0.97) | 0.004 |

| Non-fatal MI | 8 (1.75) | 8 (1.55) | 0.806 |

| TVR | 16 (3.50) | 5 (0.97) | 0.007 |

| Non-TVR | 11 (2.41) | 12 (2.33) | 0.934 |

| Stent thrombosis, definite | 3 (0.65) | 1 (0.19) | 0.266 |

Data are presented as numbers (%) for categorical variables. MACE major adverse cardiac event, MI myocardial infarction, TVR target vessel revascularization

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of low HDL-C and normal HDL-C groups. a cumulative MACE-free survival. b cumulative cardiac death-free survival. HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Ref, reference

In multivariable Cox proportional hazard model analyses, HDL-C level, BMI, hypertension, and eGFR were independent significant predictors for MACE [HDL-C, HR (95% CI) 0.95 (0.905 - 0.999), p = 0. 047; BMI, HR (95% CI) 0.84 (0.714 – 0.993), p = 0.041; hypertension, HR (95% CI) 4.80 (1.052 – 21.927), p = 0.043; eGFR, HR (95% CI) 0.981 (0.966 – 0.996), p = 0.016] after adjusting for conventional risk factors (Table 4). LVEF remained the only independent predictor for cardiac death [HR (95% CI) 0.893 (0.828 – 0.964), p = 0.004].

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for risk factors to predict MACE and cardiac death

| MACE | Cardiac death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factor | β | HR (95% CI) | p-value | β | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Univariate analysis | ||||||

| Age | 0.04 | 1.04 (1.007 – 1.066) | 0.014 | 0.10 | 1.10 (1.048 – 1.158) | <0.001 |

| Male | −0.10 | 0.90 (0.513 – 1.588) | 0.723 | −0.33 | 0.72 (0.306 – 1.677) | 0.443 |

| BMI | −0.02 | 0.98 (0.895 – 1.073) | 0.666 | −0.20 | 0.82 (0.703 – 0.947) | 0.008 |

| Current Smoking | −0.41 | 0.66 (0.354 – 1.243) | 0.200 | −0.56 | 0.57 (0.210 – 1.543) | 0.268 |

| Previous MI | −0.55 | 0.58 (0.327 – 1.026) | 0.061 | −0.92 | 0.40 (0.157 – 1.023) | 0.056 |

| Hypertension | 1.67 | 5.31 (2.113 – 13.363) | <0.001 | 1.26 | 3.51 (1.038 – 11.858) | 0.043 |

| HDL-C | −0.05 | 0.95 (0.928 – 0.981) | 0.001 | −0.08 | 0.92 (0.879 – 0.963) | <0.001 |

| LDL-C | −0.01 | 0.99 (0.986 – 1.001) | 0.098 | −0.01 | 1.00 (0.983 – 1.007) | 0.395 |

| eGFR | −0.02 | 0.99 (0.977 – 0.994) | 0.001 | −0.03 | 0.973 (0.960 – 0.986) | <0.001 |

| Hba1c | 0.02 | 1.02 (0.852 – 1.231) | 0.802 | 0.13 | 1.14 (0.880 – 1.482) | 0.319 |

| hsCRP | 0.002 | 1.00 (0.988 – 1.017) | 0.786 | 0.003 | 1.00 (0.985 – 1.022) | 0.739 |

| STEMI at admission | −0.55 | 0.58 (0.327 – 1.026) | 0.061 | −0.92 | 0.40 (0.157 – 1.023) | 0.056 |

| Primary PCI | −0.38 | 0.685 (0.397 – 1.183) | 0.175 | −1.27 | 0.28 (0.115 – 0.693) | 0.006 |

| MVD | 0.13 | 1.14 (0.649 – 2.008) | 0.647 | −0.22 | 0.80 (0.347 – 1.859) | 0.608 |

| Lesion type (B2/C) | 0.05 | 1.05 (0.466 – 2.346) | 0.914 | −0.60 | 0.55 (0.175 – 1.727) | 0.306 |

| Stent diameter ≤2.75 mm | 0.02 | 1.02 (0.490 – 2.124) | 0.958 | −1.27 | 0.28 (0.035 - 2.211) | 0.227 |

| Stent length ≥28 mm | 0.49 | 1.64 (0.842 – 3.174) | 0.146 | 0.41 | 1.51 (0.437 – 5.209) | 0.516 |

| LVEF | −0.04 | 0.96 (0.941 – 0.986) | 0.002 | −0.10 | 0.904 (0.870 – 0.939) | <0.001 |

| Statin at discharge | −0.35 | 0.71 (0.354 – 1.407) | 0.322 | −0.83 | 0.44 (0.170 – 1.113) | 0.083 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||||||

| HDL-C | −0.05 | 0.95 (0.905 - 0.999) | 0.047 | - | - | - |

| Age | −0.05 | 0.96 (0.906 – 1.006) | 0.085 | - | - | - |

| BMI | −0.17 | 0.84 (0.714 – 0.993) | 0.041 | −0.31 | 0.73 (0.537 – 1.002) | 0.051 |

| Hypertension | 1.57 | 4.80 (1.052 – 21.927) | 0.043 | - | - | - |

| eGFR | −0.02 | 0.981 (0.966 – 0.996) | 0.016 | −0.02 | 0.98 (0.954-1.004) | 0.093 |

| Stent diameter ≤2.75 mm | - | - | - | −1.81 | 0.16 (0.017 – 1.587) | 0.119 |

| LVEF | - | - | - | −0.11 | 0.893 (0.828 – 0.964) | 0.004 |

MACE major adverse cardiovascular events, HR hazard ratio, 95% CI 95% confidence interval, BMI body mass index, MI myocardial infarction, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, hsCRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, STEMI ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, MVD multi-vessel disease, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, n.d. not determined

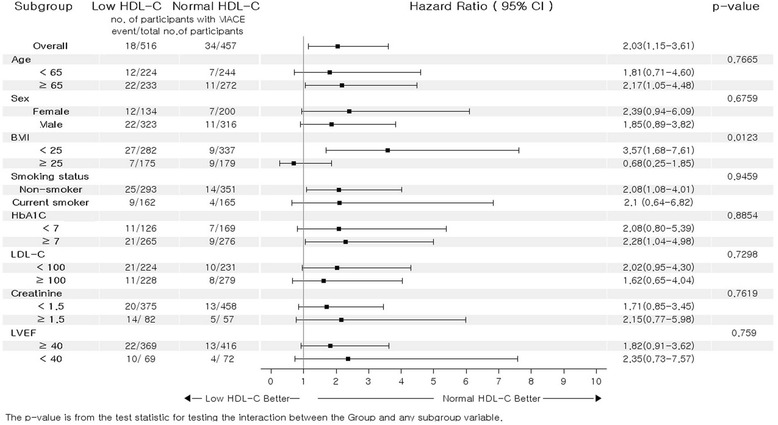

Next, the unadjusted HRs for MACE were calculated in various subgroups based on age, sex, BMI, smoking, HbA1c, LDL-C, creatinine, and LVEF (Fig. 2). Interestingly, statistical significance was found in patients with high BMI. There were no significant interactions between HDL-C and MACE among the other 7 subgroups.

Fig. 2.

Comparative unadjusted hazard ratios of MACE for subgroups. MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction

Discussion

The main findings of the present study are as follows: (1) 46.2% of diabetic patients presenting with AMI had a low HDL-C level; (2) 2-year clinical outcomes including MACE (mainly cardiac death and TVR) were poorer in diabetic patients with a low HDL-C level after AMI compared to those with a normal HDL-C level; (3) low HDL-C level remained an important risk predictor for MACE after adjusting for confounding clinical factors.

Previous community-based primary prevention studies showed that low HDL-cholesterol level was strongly associated with poor cardiovascular outcome in the general population [17, 18]. Current guidelines strongly recommend statin therapy for patients with overt atherosclerotic vascular diseases and diabetes mellitus [19, 20]. A previous study demonstrated that statin therapy increased HDL-C level by approximately 7.5%, and was associated with coronary atherosclerotic regression [21]. However, more than 40% of statin-treated patients have a persistently low HDL-C level [22, 23]. Several studies also suggested low HDL-C as an independent risk predictor, even in patients with overt atherosclerotic vascular diseases on statin therapy. Seo et al. reported that a low HDL-C level on statin therapy was associated with poor clinical outcome after PCI [12]. Ogital et al. also showed that low HDL-C was a risk factor in diabetic patients with stable coronary artery disease [13]. Recently, Lee et al. showed similar results in patients with AMI [14]. The present study showed a higher MACE rate in diabetic AMI patients with low HDL-C level compared to those with a normal HDL-C level.

On the other hand, several studies have questioned the impact of HDL-C on cardiovascular prognosis. Izuhara et al. showed that the statistical significance of low HDL-C in poor clinical outcomes disappeared after adjusting for confounding factors in patients who underwent PCI [23]. Angeloni et al. showed similar 3-year MACE rates in low and high HDL-C groups, even in patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting [24]. Ji et al. also showed no significant difference in 1-year MACE rates between the two groups in AMI patients [25].

The discrepancy among studies might be explained by several factors. First, the studies were performed in different clinical settings and had different demographic and risk profiles. The clinical situations could have affected the anti-atherogenic and anti-inflammatory function of HDL-C. Recently, many studies have focused on the function of HDL-C rather than the level. HDL-C plays an important role in atherogenesis through reverse cholesterol transport. Removing cholesterol from macrophages (called “macrophage cholesterol efflux”) is significantly associated with cardiovascular events [26, 27]. Cholesterol efflux capacity and the NO-producing effect of HDL-C were also decreased in patients with acute coronary syndrome [28, 29]. Dysfunction of HDL-C was also reported in diabetic patients [30]. These findings suggested that HDL-C dysfunction might mask the clinical significance of serum HDL-C level for cardiovascular prognosis depending on the clinical situation. In other words, the quality of HDL-C might be more significant than the quantity in selected populations. Second, the cut-off value of HDL-C could affect the results of clinical studies. Interestingly, the studies using the cut-off value of 40 mg/dL suggested that low HDL-C was an independent risk predictor [12–14]. Other studies using different cut-off values for men and women (40 mg/dL for men and 50 mg/dL for women) failed to show the significance of low HDL-C [23–25]. More importantly, 2 studies from the same AMI registry showed different results. One adopted the cut-off value of 40 mg/dL for both men and women [14], and the other study used different cut-off values for men and women (40 mg/dL for men and 50 mg/dL for women) [25]. In the present study, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of HDL-C for cardiac death showed that the area under the curve (AUC) for men was 0.722 and 0.753 for women (Additional file 1: Figure S1); optimal cut-off points with the Youden index were 38 mg/dL for men and 35 mg/dL for women. ROC curves of HDL-C for MACE showed that the AUC for men was 0.634 and 0.660 for women; optimal cut-off points with the Youden index were 38 mg/dL for men and 40 mg/dL for women. Thus, we used the same cut-off value of 40 mg/dL for both men and women. Moreover, 2015 Korean guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia adopted a criterion of below 40 mg/dL as low HDL-C for both men and women [31].

A genetic mechanism reportedly links low HDL-C and inflammatory states [32]. Hoven et al. also showed a clinical relationship between low HDL-C level and its inflammatory and oxidative phenotype [33]. Moreover, there is much experimental evidence for the beneficial effects of HDL-C [34]. Although previous clinical trials aimed at raising HDL-C failed to show promising results [35–38], new HDL-C-based strategies designed to improve HDL-C functionality instead of increasing the HDL-C level have been under development [39, 40].

There are several limitations. First, the study subjects were divided into only 2 groups. We did not address the impact of the other ranges of HDL-C level (e.g., HDL-C > 70 mg/dL or < 20 mg/dL) due to the limited patient numbers. Thus, the possible protective role of high HDL-C level or its dose–response relationship could not be investigated. Second, the current guidelines recommend statin therapy for diabetic patients regardless of their lipid profile [31, 41]. Detailed information (name and dose) on statins and other medications affecting HDL-C levels were not assessed. However, the effect of statins on HDL-C has been known to be relatively small. Moreover, our data highlighted the clinical limitations of current statin usage and proposed HDL-C as a therapeutic target despite the failures of previous trials. Third, the follow-up rate of HDL-C was only 62.0% in the present study. Data on HDL-C levels before admission were not obtained. Thus, we cannot analyze the dynamics of HDL-C. Fourth, serum uric acid level was not included and adjusted for a potential confounding factor. Although the relationship between serum uric acid level and the prognosis of acute myocardial infarction has been still controversial, serum uric acid level is a well-known surrogate marker for inflammation and atherosclerosis [42]. Unfortunately, serum uric acid level was not available in our registry. Additional data including serum uric acid level and other inflammatory biomarkers could be more informative to understanding the clinical impact of HDL-C.

Conclusions

The 2-year incidence of MACE, cardiac death, and TVR was significantly higher in diabetic patients with a low HDL-C level compared to those with a normal HDL-C level after AMI. Low HDL-C level remained an independent risk predictor for both MACE and cardiac death after adjusting for multiple risk factors.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from Bayer Korea, Co., Ltd.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from Bayer Korea, Co., Ltd. It was also mentioned on the Acknowledgements section.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

HJJ researched data and worte the manuscript. S.C. analyzed data. SJH, SH, JB, DC, YA, JP, RC, DC, JK, KH, HP, SC, JY, HK, SR, KH, KJ, SO, JL, ES, and KK collected and reviewed the data. HK and DL reviewed the manuscript and contributed to discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the submission and publication of this manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional review board of each institute and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Abbreviations

- AMI

Acute myocardial infarction

- AUC

Area under the curve

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- CK-MB

Creatine kinase-MB fraction

- DIAMOND

DIabetic acute myocardial InfarctiON disease

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HR

Hazard ratio

- hsCRP

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- MACE

Major adverse cardiovascular events

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- STEMI

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- TNT

Treating to new targets

- TVR

Target vessel revascularization

Additional file

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of HDL-C for MACE and cardiac death. (DOCX 346 kb)

Contributor Information

Hyung Joon Joo, Email: drjoohj@gmail.com.

Sang-A Cho, Email: sanga0817@naver.com.

Soon Jun Hong, Email: psyche94@hanmail.net.

Seung-Ho Hur, Email: shur@dsmc.or.kr.

Jang-Ho Bae, Email: janghobae@yahoo.co.kr.

Dong-Ju Choi, Email: djchoi@snu.ac.kr.

Young-Keun Ahn, Email: cecilyk@hanmail.net.

Jong-Seon Park, Email: pjs@med.yu.ac.kr.

Rak-Kyeong Choi, Email: yoorimbin@hanmail.net.

Donghoon Choi, Email: cdhlyj@yuhs.ac.

Joon-Hong Kim, Email: junehongk@gmail.com.

Kyoo-Rok Han, Email: krheart@hallym.or.kr.

Hun-Sik Park, Email: hspark@knu.ac.kr.

So-Yeon Choi, Email: sychoimd@hotmail.com.

Jung-Han Yoon, Email: junghany@me.com.

Hyeon-Cheol Kwon, Email: hcgwon62@gmail.com.

Seung-Woon Rha, Email: swrha617@yahoo.co.kr.

Kyung-Kuk Hwang, Email: khyungkyk@cbnu.ac.kr.

Kyung-Tae Jung, Email: jkt@eulji.ac.kr.

Seok-Kyu Oh, Email: oskcar@wonkwang.ac.kr.

Jae-Hwan Lee, Email: myheart@cnu.ac.kr.

Eun-Seok Shin, Email: sesim98@yahoo.co.kr.

Kee-Sik Kim, Email: kks7379@cu.ac.kr.

Hyo-Soo Kim, Phone: +82-2-2072-2226, Email: hyosoo@snu.ac.kr.

Do-Sun Lim, Phone: +82-2-920-5445, Email: dslmd@kumc.or.kr.

References

- 1.Piccolo R, Franzone A, Koskinas KC, Raber L, Pilgrim T, Valgimigli M, Stortecky S, Rat-Wirtzler J, Silber S, Serruys PW, et al. Effect of diabetes mellitus on frequency of adverse events in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(3):345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park KH, Ahn Y, Jeong MH, Chae SC, Hur SH, Kim YJ, Seong IW, Chae JK, Hong TJ, Cho MC, et al. Different impact of diabetes mellitus on in-hospital and 1-year mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction who underwent successful percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the Korean acute myocardial infarction registry. Korean J Intern Med. 2012;27(2):180–188. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2012.27.2.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE, Jr, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR, Jr, Jaffe AS, Jneid H, Kelly RF, Kontos MC, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130(25):2354–2394. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, Chambers CE, Ellis SG, Guyton RA, Hollenberg SM, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI focused update on primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: an update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task force on clinical practice guidelines and the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions. Circulation. 2016;133(11):1135–1147. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldbourt U, Yaari S, Medalie JH. Isolated low HDL cholesterol as a risk factor for coronary heart disease mortality. A 21-year follow-up of 8000 men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17(1):107–113. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.17.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ueshima H, Iida M, Shimamoto T, Konishi M, Tanigaki M, Nakanishi N, Takayama Y, Ozawa H, Kojima S, Komachi Y. High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels in Japan. JAMA. 1982;247(14):1985–1987. doi: 10.1001/jama.1982.03320390047040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barter P, Gotto AM, LaRosa JC, Maroni J, Szarek M, Grundy SM, Kastelein JJ, Bittner V, Fruchart JC, Treating to New Targets I HDL cholesterol, very low levels of LDL cholesterol, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(13):1301–1310. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betteridge DJ. Lipid control in patients with diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8(5):278–290. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko M, Kim MT, Nam JJ. Assessing risk factors of coronary heart disease and its risk prediction among Korean adults: the 2001 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int J Cardiol. 2006;110(2):184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heng D, Ma S, Lee JJ, Tai BC, Mak KH, Hughes K, Chew SK, Chia KS, Tan CE, Tai ES. Modification of the NCEP ATP III definitions of the metabolic syndrome for use in Asians identifies individuals at risk of ischemic heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186(2):367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huxley RR, Barzi F, Lam TH, Czernichow S, Fang X, Welborn T, Shaw J, Ueshima H, Zimmet P, Jee SH, et al. Isolated low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol are associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease: an individual participant data meta-analysis of 23 studies in the Asia-Pacific region. Circulation. 2011;124(19):2056–2064. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.028373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seo SM, Choo EH, Koh YS, Park MW, Shin DI, Choi YS, Park HJ, Kim DB, Her SH, Lee JM, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol as a predictor of clinical outcomes in patients achieving low-density lipoprotein cholesterol targets with statins after percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2011;97(23):1943–1950. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2011.225466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogita M, Miyauchi K, Miyazaki T, Naito R, Konishi H, Tsuboi S, Dohi T, Kasai T, Yokoyama T, Okazaki S, et al. Low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is a residual risk factor associated with long-term clinical outcomes in diabetic patients with stable coronary artery disease who achieve optimal control of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Heart Vessels. 2014;29(1):35–41. doi: 10.1007/s00380-013-0330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CH, Woo JS, Park CB, Cho JM, Ahn YK, Kim CJ, Jeong MH, Kim W, other Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry I Roles of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(18):e3319. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Won KB, Hur SH, Cho YK, Yoon HJ, Nam CW, Kim KB, Bae JH, Choi DJ, Ahn YK, Park JS, et al. Comparison of 2-year mortality according to obesity in stabilized patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus after acute myocardial infarction: results from the DIAMOND prospective cohort registry. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;14:141. doi: 10.1186/s12933-015-0305-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson D. Use of estimated glomerular filtration rate to assess level of kidney function. Nephrology. 2005;10:S140–S156. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00487_2.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emerging Risk Factors C, Di Angelantonio E, Gao P, Pennells L, Kaptoge S, Caslake M, Thompson A, Butterworth AS, Sarwar N, Wormser D, et al. Lipid-related markers and cardiovascular disease prediction. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2499–2506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu Q, Tian G, Zhang Y, Lu M, Lin X, Ma A. Low HDL-C predicts risk and PCI outcomes in the Han Chinese population. Atherosclerosis. 2013;226(1):193–197. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, de Jesus JM, Houston Miller N, Hubbard VS, Lee IM, Lichtenstein AH, Loria CM, Millen BE, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S76–S99. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European society of cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2016;37(3):267–315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholls SJ, Tuzcu EM, Sipahi I, Grasso AW, Schoenhagen P, Hu T, Wolski K, Crowe T, Desai MY, Hazen SL, et al. Statins, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and regression of coronary atherosclerosis. JAMA. 2007;297(5):499–508. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruckert E, Baccara-Dinet M, Eschwege E. Low HDL-cholesterol is common in European type 2 diabetic patients receiving treatment for dyslipidaemia: data from a pan-European survey. Diabet Med. 2007;24(4):388–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Izuhara M, Ono K, Shiomi H, Morimoto T, Furukawa Y, Nakagawa Y, Shizuta S, Tada T, Tazaki J, Horie T, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and cardiovascular outcomes in Japanese patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the CREDO-Kyoto registry cohort-2. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(2):632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angeloni E, Paneni F, Landmesser U, Benedetto U, Melina G, Luscher TF, Volpe M, Sinatra R, Cosentino F. Lack of protective role of HDL-C in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing elective coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(46):3557–3562. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ji MS, Jeong MH, Ahn YK, Kim YJ, Chae SC, Hong TJ, Seong IW, Chae JK, Kim CJ, Cho MC, et al. Impact of low level of high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol sampled in overnight fasting state on the clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction (difference between ST-segment and non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction) J Cardiol. 2015;65(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenson RS, Brewer HB, Jr, Davidson WS, Fayad ZA, Fuster V, Goldstein J, Hellerstein M, Jiang XC, Phillips MC, Rader DJ, et al. Cholesterol efflux and atheroprotection: advancing the concept of reverse cholesterol transport. Circulation. 2012;125(15):1905–1919. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohatgi A, Khera A, Berry JD, Givens EG, Ayers CR, Wedin KE, Neeland IJ, Yuhanna IS, Rader DR, de Lemos JA, et al. HDL cholesterol efflux capacity and incident cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(25):2383–2393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomaraschi M, Ossoli A, Favari E, Adorni MP, Sinagra G, Cattin L, Veglia F, Bernini F, Franceschini G, Calabresi L. Inflammation impairs eNOS activation by HDL in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;100(1):36–43. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hafiane A, Jabor B, Ruel I, Ling J, Genest J. High-density lipoprotein mediated cellular cholesterol efflux in acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(2):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sorrentino SA, Besler C, Rohrer L, Meyer M, Heinrich K, Bahlmann FH, Mueller M, Horvath T, Doerries C, Heinemann M, et al. Endothelial-vasoprotective effects of high-density lipoprotein are impaired in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus but are improved after extended-release niacin therapy. Circulation. 2010;121(1):110–122. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.836346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Committee for the Korean Guidelines for the Management of D 2015 Korean guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia: executive summary (English translation) Korean Circ J. 2016;46(3):275–306. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2016.46.3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laurila PP, Surakka I, Sarin AP, Yetukuri L, Hyotylainen T, Soderlund S, Naukkarinen J, Tang J, Kettunen J, Mirel DB, et al. Genomic, transcriptomic, and lipidomic profiling highlights the role of inflammation in individuals with low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(4):847–857. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holven KB, Retterstol K, Ueland T, Ulven SM, Nenseter MS, Sandvik M, Narverud I, Berge KE, Ose L, Aukrust P, et al. Subjects with low plasma HDL cholesterol levels are characterized by an inflammatory and oxidative phenotype. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamashita S, Tsubakio-Yamamoto K, Ohama T, Nakagawa-Toyama Y, Nishida M. Molecular mechanisms of HDL-cholesterol elevation by statins and its effects on HDL functions. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17(5):436–451. doi: 10.5551/jat.5405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, Grundy SM, Kastelein JJ, Komajda M, Lopez-Sendon J, Mosca L, Tardif JC, Waters DD, et al. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2109–2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Abt M, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ, Brumm J, Chaitman BR, Holme IM, Kallend D, Leiter LA, et al. Effects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(22):2089–2099. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Investigators A-H, Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, Chaitman BR, Desvignes-Nickens P, Koprowicz K, McBride R, Teo K, Weintraub W. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(24):2255–2267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Group HTC. HPS2-THRIVE randomized placebo-controlled trial in 25 673 high-risk patients of ER niacin/laropiprant: trial design, pre-specified muscle and liver outcomes, and reasons for stopping study treatment. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(17):1279–1291. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chenevard R, Hurlimann D, Spieker L, Bechir M, Enseleit F, Hermann M, Flammer AJ, Sudano I, Corti R, Luscher TF, et al. Reconstituted HDL in acute coronary syndromes. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;30(2):e51–e57. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah PK. Atherosclerosis: targeting endogenous apo A-I--a new approach for raising HDL. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8(4):187–188. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ray KK, Kastelein JJ, Boekholdt SM, Nicholls SJ, Khaw KT, Ballantyne CM, Catapano AL, Reiner Z, Luscher TF. The ACC/AHA 2013 guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in adults: the good the bad and the uncertain: a comparison with ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias 2011. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(15):960–968. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruggiero C, Cherubini A, Ble A, Bos AJ, Maggio M, Dixit VD, Lauretani F, Bandinelli S, Senin U, Ferrucci L. Uric acid and inflammatory markers. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(10):1174–1181. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.