Abstract

Background

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that destroys memory and cognitive skills. AD is characterized by the presence of two types of neuropathological hallmarks: extracellular plaques consisting of amyloid β-peptides and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins. The disease affects 5 million people in the United States and 44 million world-wide. Currently there is no drug that can cure, stop or even slow the progression of the disease. If no cure is found, by 2050 the number of alzheimer’s patients in the U.S. will reach 15 million and the cost of caring for them will exceed $ 1 trillion annually.

Results

The present paper develops a mathematical model of AD that includes neurons, astrocytes, microglias and peripheral macrophages, as well as amyloid β aggregation and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins. The model is represented by a system of partial differential equations. The model is used to simulate the effect of drugs that either failed in clinical trials, or are currently in clinical trials.

Conclusions

Based on these simulations it is suggested that combined therapy with TNF- α inhibitor and anti amyloid β could yield significant efficacy in slowing the progression of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, Mathematical modeling, Drug treatment

Background

AD is the most common form of dementia. The disease is an irreversible, progressive, brain disorder that destroys memory and cognitive skills, and eventually the ability to carry out even the simplest tasks. While the genetic inheritability of AD is in the range of 50 –80% [1, 2], the cause of the disease is mostly unknown. The disease strikes ageing people typically 65 or older, and twice more women than men. In 2015 there were more than 5 million people in the United States with AD, and 44 millions world-wide [3]. The cost of caring for AD patients in the U.S. was estimated at $226 billions for 2015 [3].

AD is characterized by the presence of two types of neuropathological hallmarks: extracellular plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). The extracellular plaques consist primarily of amyloid β-peptide (A β) deposits. The NFTs are intraneural aggregation of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) appears to be one of the early events in the progression of the disease [4]. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) on neurons membrane constitutively shed A β peptides [5]. High levels of ROS promote abnormal deposition of A β [4, 6]. Tau protein in the central nervous system (CNS) is predominantly expressed in neurons; its main role is to promote microtubles assembly and stability. Glycogen synthase kinase-type 3(GSK-3) is activated by the abnormally produced A β, and it mediates the hyperphosphorylation of tau proteins [4, 6–9].

The hyperphosphorylated tau proteins cause microtuble depolymerization and destruction, as they aggregate to form neurofibrillary tangles. This results in neuronal death and release of the NFTs to the extracellular environment [4, 10].

The non-neuronal cells in the brain consist of cells that support neurons directly, mostly astrocytes, and immune cells.

Microglias are the resident macrophages in the brain. They constitute the main active immune cells in the brain. They are activated by soluble A β oligomers which build up from the A β deposits [11, 12].

Astrocytes are in close proximity to neurons. They support neuronal cross-talk, and mediate the transport of nutrients from the blood to neurons. Astrocytes are activated primarily by TNF- α, but also by A β [10, 13–16]. Activated astrocytes produce A β, but at a smaller rate than neurons [16]. Activated astrocytes also produce MCP-1, which attracts monocytes from the blood into the plaques [17–19]. The monocytes differentiate into proinflammatory macrophages, , but may then change phenotype into anti-inflammatory macrophage. Activated microglias have two phenotypes: proinflammatory M 1 macroglia and anti-inflammatory M 2 macroglia [12, 20]. Macrophages have a major role in A β clearance [12, 20], but activated microglia are poorly phagocytic for A β compared to peripheral macrophages [21]. M 1 and macrophages are neurotoxic; they produce proinflammatory cytokines TNF- α, IL-6, IL-12 and IL-1 β [20, 22, 23]. M 2 microglias and peripheral macrophages produce anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10, IL-13, IL-4 and TGF- β [20]. The neuronal stress caused by the proinflammatory cytokines, is resisted by IL-10, IL-13 and IL-4, but nevertheless it contributes to neuronal damage and death [20, 22, 23].

There are currently no drugs that can cure AD, or stop its progression. Many clinical trials of drugs aimed at preventing or clearing the A β and tau pathology have failed to demonstrate efficacy [24–27]. Currently the only treatment of AD is by medications that are used to treat the symptoms of the disease.

The role of TGF- β is somewhat controversial [28]. On one hand, TGF- β provides protection against neuroninflammation and neurondegeneration [29–34], but on the other hand, TGF- β-induced TIAF1 interacts with amyloid fibrils to favorably support plaque formation [28], and blocking TGF- β-smad2/3 in peripheral macrophages mitigates AD pathology [35].

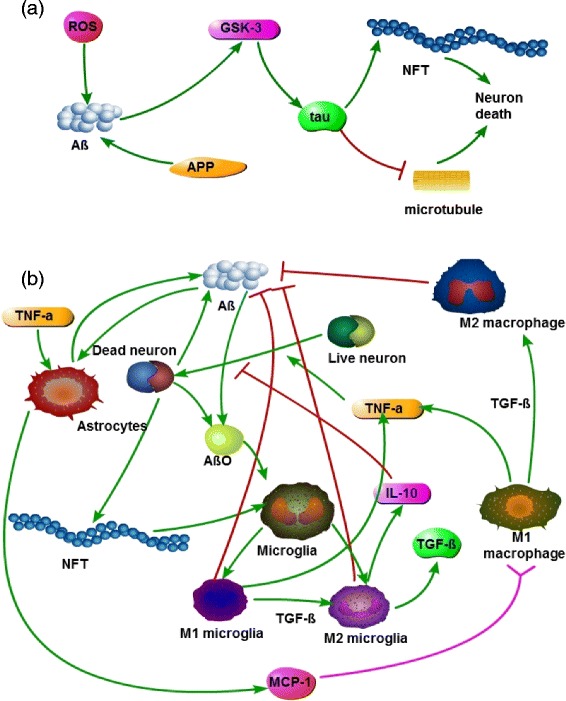

Figure 1 is a schematics of the network associated with the progression of AD. Figure 1 a shows the network within a neuron which leads from ROS to NFTs and the destruction of microtubules. Figure 1 b shows the network of activated cells, microglia, astrocyte and monocyte-derived macrophages and their effect on neurons and their microenvironment.

Fig. 1.

Schematic network in AD: a Amyloid precurser protein (APP) sheds Amyloid β peptides. ROS promotes abnormal production of A β [5, 6], which activates GSK-3 [4, 6, 8]. Activated GSK-3 mediates hyperphosphrylation of tau proteins [4, 6], which results in the formation of NFTs [10] and destruction of microtubules [4, 10], leading to neuron death. b Astrocytes are activated by [10, 16] and TNF- α [14, 15], and they produce MCP-1 [17–19], which attracts macrophages into the tissue [17, 19]. NFT activates microglias [10, 13, 15]. Activated proinflammatory microglias and microphages produce TNF- α and other proinflammatory cytokines [20, 22, 23], while anti-inflammatory microglias and macrophages produce IL-10 and other anti-inflammatory cytokines [20, 22, 23]. Dead neurons release A β and NFTs, and soluble A β oligomers activate microglia [11, 12]. Activated astrocytes secrete A β [16]. A β deposit is reduced through endocytosis by microglia and macrophages [12, 20]

In this paper we develop a mathematical model of AD. The model is represented by a system of partial differential equations (PDEs) based on Fig. 1. For simplicity we represent all the proinflammatory cytokines by TNF- α, and all the anti-inflammatory cytokines by IL-10.

We shall use our model to conduct in silico trials with several drugs: TNF- α inhibitor, anti-A β drug, MCP-1 inhibitor, and injection of TGF- β. Simulations of the model show that continuous treatment with TNF- α inhibitor yields a slight decrease the death of neurons, and anti-A β drug yields a slight decrease in the aggregation of A β over 10 years period, while the benefits from injection of TGF- β and MCP-1 inhibitor drugs are negligible. This suggests that clinical trials consider combination therapy with TNF- α and anti-A β drugs.

We note that Fig. 1 does not display neurites: the projections of axons and dendrites from the body of neurons. It is known that the aggregations of A β mediate rapid disruption of synaptic plasticity and memory [36–39]. Thus the progression of AD in terms of reduction in dendritic complexity and synaptic dysfunction will not be considered in the present paper.

We conclude the Introduction by mentioning earlier mathematical models which deal with some aspects of AD: A β polymerization [40], A β plaque formation and the role of prions interacting with A β [41, 42], linear cross-talk among brain cells and A β [43], and the influence of SORLA on AD progression [44, 45].

Methods

Mathematical model

Model’s variables

The mathematical model is based on Fig. 1 and is represented by a system of partial differential equations. Table 1 lists the variables used in the model.

Table 1.

The variables of the model; concentration and densities are in units of g/c m 3 for cells and g/m l for cytokines

| ROS (R): | Reactive oxygen species | GSK-3 (G): | Glycogen synthase kinase-type 3 |

| : | Amyloid β inside neurons | : | Amyloid β outside neurons |

| NFT (F i): | Neuronfibrillary tangle inside neurons | NFT (F o): | Neuronfibrillary tangle outside neurons |

| APP (A P): | Amyloid precursor protein | A βO (A O): | Amyloid β oligomer (soluble) |

| TNF- α (T α): | Tumor necrosis factor alpha | TGF- β (T β): | Transforming growth factor beta |

| IL-10 (I 10): | Interleukin 10 | P: | MCP-1 |

| M 1: | Proinflammatory microglias | M 2: | Anti-inflammatory microglias |

| MG (M G): | Microglias | N: | Live neurons |

| A : | Astrocytes | N d: | Dead neurons |

| Peripheral proinflammatory macrophages | : | Peripheral anti-inflammatory macrophages | |

| τ | hyperphosphorylated tau protein | H | High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) |

Equations for A β

The amyloid- β within neurons, , are constitutively released from APP at a rate and are degraded at a rate . Under reactive oxidative stress, R, is overproduced. Hence the equation for is given by

| 1 |

where N 0 is the reference density of the neuron cells in the brain.

The extracellular amyloid- β peptides satisfy the following equation:

| 2 |

where is a Michaelis-Menten coefficient. Neurons die at a rate , thereby releasing their . Hence they contribute to the growth rate of , which is the first term on the right-hand side of Eq. (2). The second term on the right-hand side of Eq. (2) represents A β constitutively released from APP [5], and the third term accounts for A β released by activated astrocytes [16]; A 0 is the reference density of the astrocyte cells in the brain. is cleared primarily by peripheral macrophages and , but also by activated microglias M 1 and M 2, so [21], and M 1 are more effective in clearing than and M 2 [46, 47] so 0≤θ<1. APP on live neurons shed A β peptides both inside the neurons (as ) and outside the neurons (as ). We assume that most are produced from dead neurons. Hence, in Eq. (2), we neglected the production of by live neurons. We also assumed that ROS increases primarily the A β that are within live neurons, and thus neglected the increase of by ROS.

Equation for τ

Tau protein is constitutively produced at some rate λ τ0. We assume that when production exceeds a threshold , GSK-3 becomes activated and it mediates hyperphosphorylation of tau. In steady state, the difference is proportional to R. Hence the equation for tau is given by:

| 3 |

We assume that initially we already have a disease state. Thus, in particular, the tau proteins are already hyperphophorylated and ROS induces increases in the production of these proteins.

Equations for NFT

The NFTs in neurons (F i) are formed from the hyperphosphorylated tau proteins [4, 6–9], and they are released to the extraceullar space (and are then labeled F 0) when the neurons die [4, 10]. Hence,

| 4 |

| 5 |

Equation for neurons

Hyberphosphorated tau proteins, forming neurofibrillary tangles, cause microtubles depolymerization and destruction, resulting in neuron death [4, 6–9]. Neuron death is also caused by stress from proinflammatory cytokines which is, however, resisted by anti-inflammatory cytokines [20, 22, 23]. For simplicity we represent all the proinflammatory cytokines by TNF- α and all the anti-inflammatory cytokines by IL-10. Hence the equation for N takes the following form:

| 6 |

where the death rates of N caused by F i and T α are assumed to depend on their saturation levels.

Equation for astrocytes

Astrocytes are activated primarily by extracellular TNF- α [14, 15], but also by [10, 16], so that

| 7 |

Equation for dead neurons

The equation for dead neurons, N d, is given by

| 8 |

where is a Michaelis-Menten coefficient. The first two terms on the right-hand side arise from the death of N cells. The last two terms account for the clearance of N d by microglias and peripheral macrophages [48].

Equation for A βO

The A βO are soluble A β oligomers and they can diffuse throughout the brain tissue [49, 50]. Their density A O satisfies the equation:

| 9 |

where is the rate by which the A O are formed from the extracellular amyloid β peptides, and accounts for the diffusion of A O.

Equation for HMGB-1

In general, when cell death occurs through necrosis, dying cells release HMGB-1 [51]. In AD, HMGB-1 is produced by dying neurons [52–54]. Hence,

| 10 |

Equations for activated microglias

Activated microglias have two phenotypes: proinflammatory M 1 and anti-inflammatory M 2. They satisfy the following equations:

| 11 |

| 12 |

where and .

Microglias can travel in the brain [55]. Activated microglias are chemoattracted to dead neurons [10, 13, 15], more precisely, to the cytokines HMGB-1 produced by N d, and this is represented by the second term of the left-hand side of Eqs. (11), (12). Microglias are activated by extracelluar NFTs [10, 13, 15], and by soluble oligomers A O [11, 12]. They become of M 1 phenotype under proinflammatory signals from TNF- α, and of M 2 phenotype under anti-inflammatory signals from IL-10. These facts are expressed by the first term on the right-hand sides of Eqs. (11), (12); is the ratio by which the activated microglias become M 1 macrophages, and is the ratio by which activated microglias become M 2 macrophages. The parameter β reflects the ratio of proinflammatory/anti-inflammatory environment, as determined by the relative ‘strength’ of T α v.s. I 10.

In addition, there is a transition M 1→M 2 under the TGF- β signaling [32], which is accounted by the second term on the right-hand side of these equations.

Equations for macrophages

Peripheral macrophages are differentiated from monocytes which migrate through the blood vessels. They satisfy a flux condition

on the boundary of the blood vessels, where n is the outward normal, M 0 is the density of the monocytes in the brain capillaries, and is a function which depends on the concentration of MCP-1. By averaging these fluxes from blood vessels, we can represent (as in [56]) the immigration of macrophages into the brain tissue by a term . We assume that the incoming macrophages divide into and phenotype depending on the relative concentrations of TNF- α and IL-10 [47]. Macrophages can also change phenotype to macrophages under signaling by TGF- β. We finally note that because of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) we do not include diffusion of peripheral macrophages, but we do include chemotaxis by amyloid- β plaques or, more specifically, by the soluble A O [17–19]. Hence peripheral macrophages satisfy the following equations:

| 13 |

| 14 |

where and [56].

Equations for TGF- β, TNF- α MCP-1 and IL-10

T β and IL-10 are produced by M 2 microglia and macrophages. TNF- α is produced by proinflammatory macrophages M 1 and . Hence the equations for T β, T α and I 10 have the following form:

| 15 |

| 16 |

| 17 |

MCP-1 is produced by activated astrocytes [17–19] and by microglias [12], which are assumed to be of M 2 phenotype. Hence

| 18 |

The estimates of parameters in Eqs. (1)–(18) are given in “Appendix".

Results and discussions

We simulate the model (1)-(18) in a rectangular domain Ω={(x,y),0≤x≤1,0≤y≤1}. We assume that

| 19 |

We take initial values, for each variable X, to be below (or above) the expected steady state for X, if X is expected to grow (or decrease) with the progression of the disease. A specific choice is given below, but the simulations do not change, after a short time, with other choices:

| 20 |

We also prescribe the value of ROS in Eqs. (1), (3) by

| 21 |

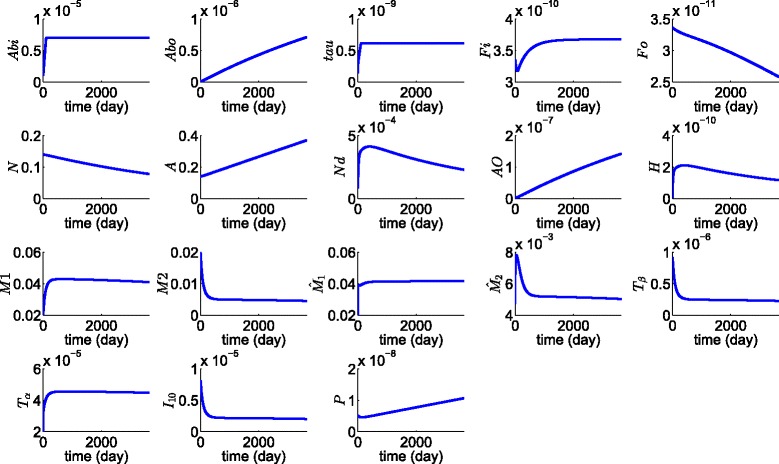

Figure 2 shows the average density of all the 18 variables of the model over a period of 10 years. We first observe that, for all the species that tend to a steady state in Fig. 2, the steady states are approximately the same as those that we assumed in estimating some of the model parameters. Thus the steady state values of and I 10 are approximately equal to the values assumed in “Appendix”. We conclude that estimates of the parameters which were based on steady state assumptions on macrophages, microglias and the half-saturation parameters are consistent with the simulation results.

Fig. 2.

Average concentration of cytokines and average density of cells. All the parameters are as in Tables 2 and 3

We next observe that neurons are dying at approximately the rate of 5% a year, which was one of our important assumptions that was based on clinical data. We also note that, as the disease progresses, the plaque of A β peptides, , and the soluble A β oligomers, A O, are increasing; reaches the level of 7×10−6 g/ml, in agreement with clinical data [57], and the assumed average of A O concentration, , is indeed in good approximation to the average of the profile of A O in Fig. 2. The assumed average of the F o concentration, , is also in good agreement with the average of the profile of F o in Fig. 2.

We note that N d nearly stabilizes over time, at the level assumed in “Appendix," which means that, over time, macrophages and microglias clear debris of dead cells at nearly the same rate at which neurons are dying. Hence becomes very small over time, resulting in significant decline in extracellular NFT, while intracellular NFTs (F i) maintain a comparatively high level.

We finally note that the density of activated astrocytes is slightly increasing in agreement with a mouse model [58] which reports that astrocytes become increasingly prominent with the progression of the disease. The increase in A causes P also to increase, and the average of P is approximately equal to our estimate of K P in S.I.

Anti-Alzheimer drugs

Until now, all clinical trials aimed to develop drugs that can cure AD have failed. There are currently no drugs that can prevent, stop or even delay the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, and there are many ongoing clinical trials. According to the 2016 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures, and the National Institute of Aging, if no cure is found, by 2050 the number of alzheimer’s patients in the U.S. will reach 15 millions and the cost of caring for them will exceed $ 1 trillion annually.

Avenues for AD therapies include prevention of build up of plaque (anti-amyloid drugs), preventing tau aggregation, and reducing inflammation. Clinical trials are concerned with both safety and efficacy. Here we shall use our mathematical model to conduct in silico trials with several drugs, addressing only the question of efficacy.

Treatment for AD causes changes in the densities of cells and concentrations of cytokines. In order to determine the efficacy of a drug, we should observe (i) to what extend it decreases the death rate of N, since slowing the death of neurons will improve cognition of patients; and (ii) to what extend it decreases , since A β aggregation mediates rapid dysfunction of synaptic plasticity and dendritic channels thereby causing memory loss [36–39].

TNF- α inhibitor

Since TNF- α is implicated in generating neurotoxicity which leads to death of neurons, TNF- α inhibitor (etanercept) has been considered as a drug for Alzheimer’s patients [59]. In 2015 clinical trials phase 2 [60] the drug has shown some favorable trends but with “no statistically significant changes in cognition.” Since there were no serious adverse events, it was suggested that a larger, broader group needs to be tested before recommending etanercept for use for general Alzheimer patients.

We shall apply our model to determine how this TNF- α inhibitor affects AD patients. We use the following procedure:

Run the model for 300 days in order to ensure that AD has been diagnosed in patients;

Apply continuous treatment by the drug from day 300 until the end of 10 years.

During treatment, the effect of the drug is to replace Eq. (17) for TNF- α by the equation

| 22 |

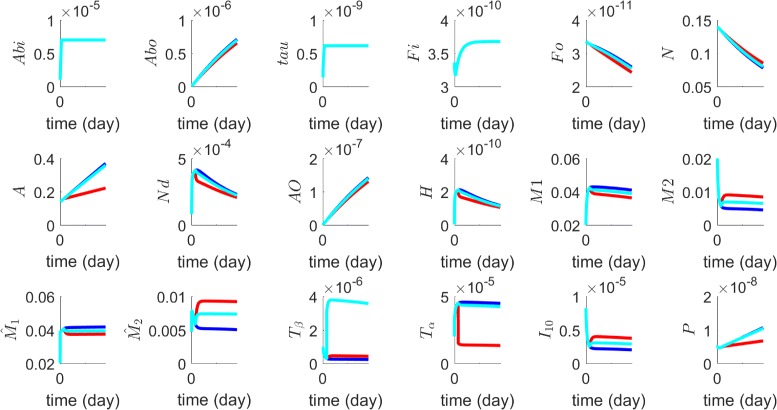

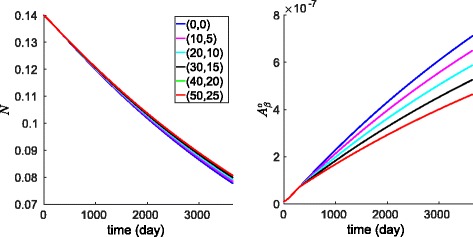

where f is proportional to the amount of etanercept. We note that since etanercept is a soluble TNF receptor fusion protein, it stabilizes TNF- α [61] and thus TNF- α is diminished at rate f T α. The red profiles in Fig. 3 show the result of the treatment with , compared to no treatment.

Fig. 3.

Anti-TNF- α drug (red), etanercept, with ; TGF- β injection. (light-blue) with . Dark-blue color corresponds to no treatment, and where several profiles nearly coincide, they are all colored by light-blue. All the other parameters are as in Tables 2 and 3

TGF- β injection

TGF- β is an anti-inflammatory cytokine which induces phenotype change from proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory macrophages. It was suggested that TGF- β mitigates AD pathology [29–34].

We note that the effect of T β injection is to decrease M 1 and (see Eqs. (11), (13)), which results in a decrease in T α (by Eq. (17)) and hence in a decrease in neuronal death rate. To model the treatment by injection of TGF- β we replace Eq. (15) for T β by the equation

| 23 |

where g is proportional to the amount of injected TGF- β. In steady state, T β maintains the level of , while its degradation rate is . Hence the source of T β in steady state is . We take g to be 10 times this source, that is . We then follow the same treatment procedure for TNF- α inhibitor. The light-blue profiles in Fig. 3 show the results of the treatment, compared to no treatment.

Anti-A β drugs

There are several drugs in Phase 3 clinical trials that aim to reduce the effect of A β aggregation [62]. Among them is aducanumab, which is thought to be microglia-mediated phagocytosis and clearance of A β [63, 64]. In our model, this drug will cause a decrease in the concentration of soluble , by replacing Eq. (2) by the equation

| 24 |

where h is proportional to the amount of the dozing level; we take h=10.

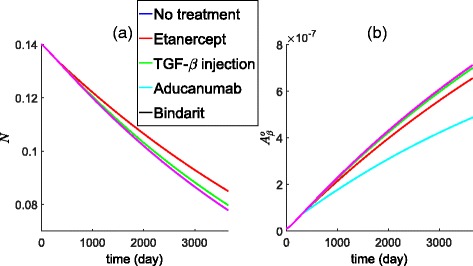

Figure 4 shows the efficacy of several drugs in terms of N and . The lowest curve in Fig. 4 a, and the highest curve in Fig. 4 b, correspond to the case where the curves of no treatment and several other drugs coincide; these drugs have negligible efficacy. Following the same treatment procedure as in the case of TNF- α inhibitor, Fig. 4 shows no efficacy of aducanumab in terms of N but significant efficacy in terms of in comparison to no treatment and to treatments by TNF- α inhibitor and TGF- β injection.

Fig. 4.

Treatment with etanercept (decreasing T α degradation rate by 10 fold), TGF- β injection (increasing its constitutive source by 10 fold), aducanumab (increasing the clearance rate of by 10 fold), and bindarit (increasing MCP-1 natural degradation by 10 fold). In a, the profiles of no treatment, bindarit and aducanumab coincide. In b, no treatment and bindarit coincide. The lowest curve in Fig. 4 a, and the highest curve in Fig. 4 b, correspond to the case where the curves of no treatment and several other drugs coincide; these drugs have negligible efficacy

MCP-1 inhibitor

Bindarit was shown to inhibit CCL2 (MCP-1) in brain tissue [65]. Hence it decreases (by Eq. (13)), which results in a decrease in T α (by Eq. (17)) and thus also in a decrease in neuronal death rate. Bindarit was also reported to inhibit A β-induced neuronal death in vitro [66]. Hence it has a therapeutic potential in the treatment of neuroninflammatory/neurodegenerative diseases like AD [66]. We can conduct in silico trial with bindarit by revising Eq. (18) for P, replacing it with the equation

| 25 |

with k=10 Following the treatment procedure as in the case of of TNF- α inhibitor, Fig. 4 shows no efficacy of the drug in terms of N and in comparison to no treatment.

Methylthiomnium chloride (MTC) is the first identified tau aggregation inhibitor currently in Phase 3 trial [27]. In our model the drug will cause a decrease in the production of tau proteins and in their ability to turn into NFT. We model this by multiplying the production terms λ τ0 and λ τ by 1/10. Following the procedure as in case of TNF- α inhibitor, we found that the drug has almost negligible efficacy (not shown here).

Combination therapy

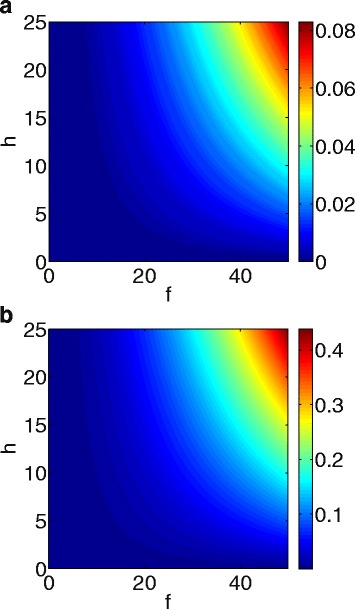

The results of Fig. 4 suggest that a combination therapy with etanercept (TNF- α inhibitor) and aducanumab (anti-A β drug), under the same ’10-fold’ amount, could both slow the death rate of neurons and decrease the growth of A β in a significant way. Figure 5 shows the dynamics of N and under such combination of drugs with different proportions of fold numbers: (etanercept,aducanumab)=(0,0) (no drugs), (10,5), (20,10), (30,15), (40,20) and (50,25). The reduction in the death of neurons, after 10 years, compared to the case of no drugs, is 3.8, 5.2, 6.4, 7.9 and 9.2%, respectively, and the respective reduction in the concentration of A β is 21, 32.2, 43.6, 53.9 and 64.1%.

Fig. 5.

Combined treatment with etanercept fold number f and aducanumab fold number h for several values of (f, h)

We next consider combined therapy for any value of etanercept (f) and aducanumab (h). We define the N-efficacy of (f, h), E N(f,h), to be

where the density N is computed at the end of 10 years. Similarly we define the anti- efficacy by

where the concentration is computed also at the end of 10 years.

Figure 6 is an efficacy map of the combined therapy with f in range of (0,50) and h in the range of (0,25). For any pair (f,h) the color columns in Fig. 6a and 6b show the efficacy for N and anti-.

Fig. 6.

Efficacy maps. Etanercept (with fold number f) varies along the horizontal axis, and aducanumab (with fold number h) varies along the vertical axis. The column vector indicates the efficacy of treatment for any pair (f,h): a N-efficacy; b Anti- efficacy

We see that the efficacy of the combined therapy is very small if f<20 or h<10, and it increases sharply with f and h in the region where {40<f<50,20<h<25}.

From Fig. 6 we see that anti-A β antibody decreases the external concentration of A β () with efficacy less than 0.5 (h=20, f=0). Higher efficacy requires T α inhibitor (h=20, f=20) which will protect neuron from death and prevent astrocytes activation, and thereby reduce . This result can be explained by our assumptions in Eq. (2) where we neglected the production of by live neurons and the increase of by ROS.

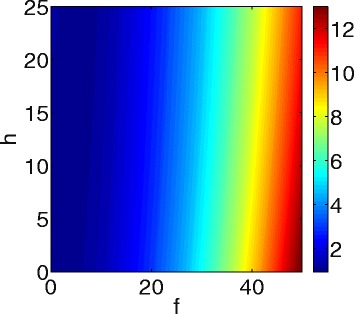

The PK/PD literature employs the concept of combination index (ϕ) in order to assess the level of synergy between two drugs [67]. This concept was used in simulations of several diseases (e.g. cancer and microbial diseases) in order to determine optimal dosage regimens [67–69]. Since in our AD model it is not clear how to define ϕ, and no data are available to evaluate ϕ, we shall, instead, introduce the following concept, for example in the case of etanercept and aducanumab:

We say that these two drugs at concentrations f and g have positive synergy with respect to N if E N(f,g)>E N(2f,0) and E N(f,g)>E N(0,2g). We accordingly define the synergy index σ N=σ N(f,g) by

Thus, σ N>1 means positive synergy and σ N<1 means negative synergy. The above definition depends on the doses f, g. If σ N is large then the combination therapy at total amount f+g is much more effective than a single therapy, at the total same amount, in reducing the death rate of N. If σ N<1 then a single drug is preferable. Similarly one can define the synergy index with respect to . Figure 7 shows the synergy index σ N for (f, g) in the range 0<f<50 and 0<g<25. We see that there is a positive synergy between etanercept (f) and aducanumab (h). Furthermore, given a total amount A of the combined drugs, so that f+h=A, the synergy increases as f/g increases. This suggests that in an optimal regimen f should be significantly larger than h, provided negative side-effects are discounted.

Fig. 7.

Synergy map for combination therapy with etanercept (f) and aducanumab (h)

The synergy map for is similar to that of σ N (not shown here), and so the synergy increases when f/g is increased.

From Fig. 5 we see that although the amyloid level are controlled, cell death levels do not decrease significantly. This may suggest that other combinations of drugs may target complimentary pathways more efficiently. For example, it was suggested in [70] that Amyloid β and tau combine to induce neuron into cell cycle, which leads to cell death; accordingly, one could explore using anti-A β and anti tau aggregation in combination therapy.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis on the model parameters can support the robustness of the simulation results. But it can also suggest what drugs do not work and what drugs are more likely to work. We conducted sensitivity analysis on parameters associated with production and removal rates of , death rates of N, and production rates of TNF- α, TGF- β and MCP-1:

where we varied λ N, λ A, d NF, d NT between and twice their value in Tables 2 and 3, and varied γ, δ, ξ, ε between and 2.

Table 2.

Parameters’ description and value

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Diffusion coefficient of A βO | 4.32×10−2 c m 2 day −1 estimated | |

| D H | Diffusion coefficient of HMGB-1 | 8.11×10−2 c m 2 day −1 estimated |

| Diffusion coefficient for TNF- α | 6.55×10−2 c m 2 day −1 estimated | |

| Diffusion coefficient of TGF- β | 6.55×10−2 c m 2 day −1 estimated | |

| Diffusion coefficient of IL-10 | 6.04×10−2 c m 2 day −1 estimated | |

| D P | Diffusion coefficient of MCP-1 | 1.2×10−1 c m 2 day −1 estimated |

| Production rate of | 9.51×10−6 g/ml/day estimated | |

| λ N | Production rate of by neuron | 8×10−9 g/ml/day estimated |

| λ A | Production rate of by astrocytes | 8×10−10 g/ml/day estimated |

| λ τ0 | Production rate of tau proteins in health | 8.1×10−11 g/ml/day estimated |

| λ τ | Production rate of tau proteins by ROS | 1.35×10−11 g/ml estimated |

| λ F | Production rate of NFT by tau | 1.662×10−3/day estimated |

| Production/activation rate of astrocytes by TNF- α | 1.54/day estimated | |

| Production/activation rate of astrocytes by | 1.793/day estimated | |

| Production rate of A βO | 5×10−2/day estimated | |

| λ H | Production rate of HMGB-1 | 3×10−5/day estimated |

| λ MF | Production/activation rate of microglias by NFT | 2×10−2/day estimated |

| λ MA | Production/activation rate of microglias by astrocytes | 2.3×10−3/day estimated |

| Rate of M 1→M 2 | 6×10−3/day estimated | |

| Rate of | 6×10−4/day estimated | |

| Production rate of TGF- β by M | 1.5×10−2 day −1 [56, 99] | |

| Production rate of TGF- β by | 1.5×10−2 day −1 [56, 99] | |

| Production rate of TNF- α by M 1 | 3×10−2 day −1 estimated | |

| Production rate of TNF- α by | 3×10−2 day −1 estimated | |

| Production rate of IL-10 by M 2 | 6.67×10−3 day −1 [47, 90] | |

| Production rate of IL-10 by | 6.67×10−3 day −1 [47, 90] | |

| λ PA | Production rate of MCP-1 by astrocytes | 6.6×10−8 day −1 estimated |

| Production rate of MCP-1 by M 2 | 1.32×10−7 day −1 estimated | |

| θ | M 2/M 1 effectivity in clearance of | 0.9 estimated |

| α | Flux rate of macrophages | 5 estimated |

| β | Proinflammatory/anti-inflammatory ratio | 10 estimated |

| γ | I 10 inhibition ratio | 1 estimated |

Table 3.

Parameters’ description and value

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Degradation rate of | 9.51/day [82] | |

| Degradation rate of | 9.51/day [82] | |

| Clearance rate of by microglia | 2×10−3/day estimated | |

| Clearance rate of by macrophages | 10−2/day estimated | |

| d τ | Degradation rate of tau proteins | 0.277/day [88] |

| Degradation rate of intracellular NFT | 2.77×10−3/day estimated | |

| Degradation rate of extracellular NFT | 2.77×10−4/day estimated | |

| d N | Death rate of neurons | 1.9×10−4/day estimated |

| d NF | Death rate of neurons by NFTs | 3.4×10−4/day estimated |

| d NT | Death rate of neurons by TNF- α | 1.7×10−4/day estimated |

| Clearance rate of dead neurons by M | 0.06/day estimated | |

| Clearance rate of dead neurons by | 0.02/day estimated | |

| d A | Death rate of astrocytes | 1.2×10−3 day −1 estimated |

| Death rate of M 1 microglias | 0.015 day −1 [47, 74] | |

| Death rate of M 2 microglias | 0.015 day −1 [47, 74] | |

| Death rate of M 1 macrophages | 0.015 day −1 [47, 74] | |

| Death rate of M 2 macrophages | 0.015 day −1 [47, 74] | |

| Degradation rate of A βO | 0.951/day estimated | |

| d H | Degradation rate of HMGB-1 | 58.71/day [95] |

| Degradation rate of TNF- α | 55.45 day −1 [47, 74] | |

| Degradation rate of TGF- β | 3.33×102 day −1 [56, 99] | |

| Degradation rate of IL-10 | 16.64 day −1 [47] | |

| d P | Degradation rate of MCP-1 | 1.73 day −1[47, 74] |

| R 0 | Initial inflammation by ROS | 6 estimated |

| M 0 | Monocytes concentration in blood | 5×10−2 estimated |

| N 0 | Reference density of neuron | 0.14 g/c m 3 estimated |

| Source of microglia | 0.047 g/c m 3 estimated | |

| A 0 | Reference density of astrocytes | 0.14 g/c m 3 estimated |

| Michaelis-Mention coefficient for | 7×10−3 g/ c m 3 estimated | |

| Michaelis-Mention coefficient for N d | 10−3 g/ml estimated | |

| Half-saturation of IL-10 | 2.5×10−6 g/ c m 3 estimated | |

| Half-saturation of TGF- β | 2.5×10−7 g/ml [90] | |

| K M | Half-saturation of microglias | 0.047 g/ml estimated |

| Half-saturation of macrophages | 0.047 g/ml estimated | |

| Half-saturation of M 1 microglias | 0.03 g/ml estimated | |

| Half-saturation of M 2 microglias | 0.017 g/ml estimated | |

| Half-saturation of macrophages | 0.04 g/ml estimated | |

| Half-saturation of macrophages | 0.007 g/ml estimated | |

| Half-saturation of intracellular NFTs | 3.36×10−10 g/ml [89] | |

| Average of extracellular NFTs | 2.58×10−11 g/ml estimated | |

| Average of of A βO | 1×10−7 g/ml estimated | |

| K P | Half-saturation of MCP-1 | 6×10−9 g/ml estimated |

| Half-saturation of TNF- α | 4×10−5 g/ml estimated |

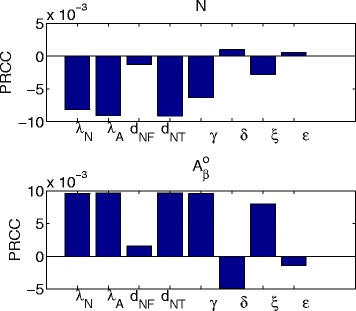

Following the sensitivity analysis method described in [71], we performed Latin hypercube sampling and generated 2000 samples to calculate the partial rank correlation coefficients (PRCC) and p-values with respect to the density of N and with respect to the concentration of at time t=10 years. The results are shown in Fig. 8. All the p-values were less than 0.01. A positive PRCC (i.e. positive correlation) for N means that an increase in the parameter will increase the number of live neurons. A negative PRCC for N means that an increase in the parameter will decrease the number of live neurons. Similarly, a positive (negative) PRCC for means that an increase in the parameter will increase (decrease) the concentration of . Thus, for example, we see that d NF and d NT are negatively correlated to N and positively correlated to . This is not surprising since, with an increase in d NF and d NT, more neurons die (so N decreases) and as a result more A β emerge from the increasingly dying neurons, thus raising the concentration of . The fact that the correlation coefficients of d NT are significantly larger than the correlation coefficients of d NF, suggests that a drug which blocks TNF- α would be more effective than a drug which clears the F i. The other PRCC values can also be seen to be consistent with the model dynamics.

Fig. 8.

The PRCC values of parameter for sensitivity analysis

We observe that ε is negatively correlated to . Indeed, if ε is increased, more are cleared out (by Eq. (2)). To see how this affects N we note that if is decreased then A O decreases (by Eq. (9)) and correspondingly M 1 decreases (by Eq. (11)), and then T α decreases (by Eq. (17)); so we may expect N to increase, but perhaps not much, since we have ignored other indirect interactions from the model. From Fig. 8 we see that ε is indeed positively correlated to N but the correlation is small. The correlation levels of ε with respect to N and suggest that an anti-A β drug, like aducanumab, will have some benefits in reducing Amyloid β, but little benefit in reducing death of neurons. This is also seen from Fig. 4.

Conclusion

AD is an irreversible progressive neuroninflammatory/neurodegenerative disease that destroys memory and cognitive skills. Currently there is no drug that can cure, stop, or even slow the progression of the disease. Life expectancy at diagnosis is 10 years, and, at death, 50% of the brain neurons have already died. AD patients show abnormal aggregation of beta-amyloids () and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins. NFTs destroy microtubles in neurons, which results in neurons death. Soluble oligomers activate microglias (the resident macrophages in the brain), thereby initiating inflammatory response. Additionally, peripheral macrophages, responding to cue from MCP-1 produced by astrocytes, are attracted to the brain and increase the inflammatory environment, which is harmful to neurons.

Figure 1 is a schematic network of AD: it includes neurons, astrocytes, microglias, peripheral macrophages, β-amyloids, tau proteins, and several cytokines involved in the cross-talk among the cells. In the present paper, we developed a mathematical model of AD based on Fig. 1. The model can be used to explore the efficacy of drugs that may slow the progress of the disease. We conducted several in silico trials with several drugs: etanercept (TNF- α inhibitor), injection of TGF- β, aducanumab (Anti-A β drug) and bindarit (MCP-1 inhibitor). We found that at ’10-fold’ level, etanercept has the largest efficacy in slowing death of neurons, while aducanumab has the largest efficacy in reducing the aggregation of , although these efficacies were quite small. Based on these findings we propose that clinical trials should use a combination therapy with etanercept (f) and aducanumab (h). In Fig. 6 we developed efficacy maps for any combination therapy with 0<f<50 and 0<h<25, and we used this map to derive, in Fig. 7, a synergy map for σ N=σ N(f,g). Figure 7 shows that the synergy between f and g increases if f/g increases, while f+g is kept fixed. This suggests that in an optimal regimen with fixed total amount, A, of the drugs, f should be significantly larger than h. We did not consider here, however, adverse side effects that are likely to limit the amount of drugs that can be given to a patient. When these limits become better known, one could then proceed to determine the optimal combination of etanercept and aducanumab for slowing the progression of AD.

The mathematical model developed in this paper depends on some assumptions regarding the mechanism of interactions involving amyloid, tau and neunofilaments in AD. There are currently not enough data to sort out competing assumptions. Hence the conclusion of the paper regarding combination therapy should be taken with caution.

Our mathematical model focused on the progression of AD in terms of neurons death and amyloid β aggregation. But dendritic pathologies also play an important role in the disease. Dendritic abnormalities in AD include dystrophic neuritides, reduction in dendritic complexity and loss in dendritic spines [36, 37]. In particular, A β plaques affect dendritic channels, and NFT mediates synaptic dysfunction [36–39]. Recent studies also begin to address white matter degeneracy that could help identify high risk of AD [72].

Appendix

Parameter estimation

In the sequel, in an expression of the form in the context of activation, the half-saturation parameter K X is taken to be the steady state of the species X provided X tends to a steady state. Hence in a steady state equation this factor is equal to . If X does not tend to a steady state then the parameter K X will be taken to be the estimated average of X over a period of 10 years, the average survival time of AD patients [73]. In an expression of the form (where γ=γ(X)) in the context of inhibition, K X is again the half-saturation of X, so that in steady state the inhibition is 1/(1+γ). If cells Y phagocytose species X, then the clearing rate is proportional to where the Michaelis-Menten constant depends only on the ‘eating capacity’ of Y, so has no relation to the half-saturation of X.

Diffusion coefficients

The diffusion coefficient of proteins (Y) are proportional to , where M Y is the molecular weight [74]. Accordingly, we have the following relation [75]:

where M V and D V are the molecular weight and the diffusion coefficient of VEGF. Since D V=8.64×10−2 c m 2 day −1[76], M V=24 kDa [76], M P=8.9 kDa [77], kDa [78], kDa [79], kDa [46], and M H=29 kDa [80], we get D P=1.20×10−1 c m 2 day −1, c m 2 day −1, c m 2 day −1, c m 2 day −1 and D H=8.11×10−2 c m 2 day −1.

Molecular weight of A β is 24 kDa [81], so in soluble state its diffusion coefficient would be 8.64×10−2 c m 2 day −1. We assume that soluble oligomer A β O has a smaller diffusion coefficient, namely, c m 2 day −1.

Eq. (1)

By [82], the half-life of is 1.5–2 h in mice. Hence =9.51 /day. Membrane proteins APP shed amyloid β, some end up inside the cell and some outside the cell. We assume that in healthy steady state , however the simulation results do not change appreciably if we take . According to [57], the density in brain-gray matter of is approximately 1000 ng/g in control and 7000 ng/g in AD. Hence, from the steady state of Eq. (1) in a healthy normal case, g/ml and = 9.51×10−6 g/ml/day. From the steady state of Eq. (1) in AD and Eq. (21) we then get that R 0=6.

The brain has 75% water and 60% of its dry matter is fat. We assume that the average density of brain tissue is 1 g/c m 3. The human brain has 100 billion neurons, and its weight is approximately 1400 g, so its volume is approximately 1400 ml. Hence its neurons number density is 7×107 neurons/ c m 3. The diameter of neurons is 16 μ m [83]. Accordingly, we estimate the volume of 1 neuron to be 2×10−9 c m 3, and the neurons density is then 7×107×2×10−9 g/c m 3, that is N 0=0.14 g/c m 3.

Eq. (2)

The number of neurons is three times the number of microglia [55], hence g/ml.

By [16] an astrocyte produces much less A β than a neuron, so we take .

Microglias are the first responders to NFTs and A βO. Peripheral macrophages arrive later, and their immune response may perhaps exceed that of microglia, but this is currently not known [12, 84]. We assume that in steady state the microglias density M and the peripheral macrophages density are equal, so that g/ml. Motivated by the inflammatory immune attack in AD [85], we assume that, in steady state, the proinflammatory macrophages exceed the anti-inflammatory macrophages, and that proinflammatory peripheral macrophages exceed the proinflammatory microglias. Thus, in steady state, , M 1>M 2 and , and we take , , , .

Activated microglias are poorly phagocytic for A β compared to peripheral macrophages [6]. Accordingly we take

Taking /day, we then have

We assume that and M 1 are more effective than and M 2 in clearing A β, and take θ=0.9.

We assume that survival time of patients with AD is 10 years, and that at the end-stage 50% of their neurons have died [73]. Hence, the death rate of N is /day.

By [57], g/ml. We assume that the clearance of by macrophages and microglias is nearly unlimited (i.e., it is almost linear in ) by taking g/ml. To estimate λ N, we first consider the steady state of Eq. (2),

To estimate the average of , we use the equation

so that

The values of for 500<t<1000 days vary very little, i.e., from 1.8×10−5 g/ml/day to 1.9×10−5 g/ml/day. We take g/ml/day as the average of over 10 years, but other choices do not affect significantly our simulation results. We then get that λ N=4×10−9 g/ml/day.

The estimate of λ N was based on the steady-state assumption in Eq. (2). However, in AD the A β peptides are continuously aggregating, so that the steady state assumption needs to be revised. We do this by increasing the value of λ N: we take λ N=2×4×10−9= 8×10−9 g/ml/day, and then λ A=8×10−10 g/ml/day.

The number of astrocytes is approximately equal to the number of neurons [86, 87], hence A 0=N 0=0.14 g/ml.

Eq. (3)

Half-life of tau proteins is 60 hours [88]. Hence =0.277/day. Concentration of tau proteins is in healthy normal individuals is 137 pg/ml and, in AD, 490 pg/ml [89]. From the steady state of Eq. (3) in the healthy case, we have λ τ0=d τ τ, where τ=137 pg/ml. Hence λ τ0= 3.78×10−11 g/ml/day. Similarly, λ τ0+λ τ R=d τ τ in AD, where τ=490 pg/ml. Hence we have λ τ R=8.1×10−11 g/ml, or λ τ=1.35×10−11/day.

Eqs. (4) and (5)

We assume that neurofibrillary tangles inside neurons are much more stable than tau proteins, taking /day. We also assume that extracellular NFTs do not degrade as fast as internalized NFTs, taking /day.

We also assume that 60% of the hyperphosphorglated tau proteins become neurofibrillary tangles. From the steady state of Eq. (4) we then have that . Hence λ F=1.662×10−3/day.

Eq. (6)

It is not known whether the rate of death of neurons caused by NFT is larger or smaller than the death rate caused by T α. We take d NF=2d NT, but the simulation of the model in the case where d NT=2d NF are very similar (not shown here). Assuming that at steady state of Eq. (6) the concentrations of F i, T α and I 10 are at half-saturation, we get , so that /day and /day. In particular, if γ=1 then d NF=2.4×10−4/day and d NT=1.7×10−4/day. We take g/ c m 3 (which is somewhat larger than the estimated half-saturation of I 10 in lung inflammation [47, 90]). We assume that in AD, 60% of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins (whose concentration in disease is 490 pg/ml [89]) are in NFT form, so that pg/ml= 2.94×10−10 g/ml. In [89] the concentration of tau protein was taken uniformly in the tissue of patients. We assume, however, that the concentration of NFT is higher inside neurons than outside neurons, and take g/ml, g/ml. From the steady state of Eq. (17) and the estimates of and (see under Eq. (17) below) we get T α=4×10−5 g/ml, so that g/ml.

Eq. (7)

We take the half-life of astrocytes to be the same as the half-life of ganglionic glial cells, that is, 600 days [91]. Hence d A=1.2×10−3/day. We assume that the activation of astrocytes is due more to TNF- α than to A β, and take . By the steady state of Eq. (7) we then get /day, and /day. Actually, in a mouse model of AD, the number of activated astrocytes is increasing [58]. So we compensate for this by increasing both and by a factor 1.1, taking /day and /day.

Eq. (8)

In mice experiments [92], macrophages phagocytosed apoptotic cells at rates that varied in the range 0.1–1.27/h. We assume that necrotic cells (and their debris) in human brain are phagocytosed by peripheral macrophages at rate /day. We also assume that microglia play a greater role in clearing necrotic neurons, and take =0.6/day. We also take g/ml.

Eq. (9)

We assume the degradation rate of A O is much slower than that of , taking /day. The ratio of soluble A O to total is approximately [93].

From the steady state of Eq. (9) we then get /day.

The estimate of was based on the steady-state assumption in Eq. (9). However, in AD the soluble A β oligomer is continuously increasing, following the increase in , so the steady-state assumption needs to be revised. We do this by increasing the above value of λ AO, taking the new value to be λ AO=5×10−2/day.

Eq. (10)

Concentration of HMGB-1 in neurons is 1.3 n g/m l [94], hence H=0.14×1.3 ng/ml= 1.8×10−10 g/ml. Half-life of HMGB-1 is 17 minutes [95], so that d H=58.71/day. We assume that N d stabilizes somewhere below 2.5×10−4 g/ml. From the steady state of Eq. (10), we then get λ H=3×10−5/day.

Eqs. (11) and (12)

We take /day [47, 90]. Then, our assumption (under Eq. (2)) that suggests that β>1. We take β=10.

We take g/ml and α=5. In the absence of data, we take the production rate λ MF of macrophages by NFT to be the same as the production rate under stimulation by M. Tuberculosis in [90], namely, λ MF=2×10−2/day. We assume that production rate of macrophages by NFT is larger than the production rate by A O, and take λ MA=2.3×10−3/day.

By [57] the concentration of A β in AD is 7×10−6 g/ml and, by [55], the ratio of A O to is , so that g/ml.

We assume that more NFT reside within neurons than outside them, so that is smaller than . Recalling that g/ml, we take g/ml.

The coefficient is the rate by which TGF- β affects the change of phenotype from M 1 to M 2. In the case of infection in the lung by M. tuberculosis, under inflammatory conditions caused by the pathogen, /day [90]; we take it to be the same in the present case. We take g/ml, and g/ml.

Eqs. (13) and (14)

Peripheral macrophages immigrate into the brain of AD [96, 97]. We assume that, because of the BBB, the concentration of monocytes in the brain capillaries must be significantly higher than the concentration of peripheral macrophages already in the tissue. Recalling that in steady state g/ml, we take M 0=0.05 g/ml. The parameter α was estimated by 5, in order to make the asymptotic behavior of in the simulations agree with its assumed steady state of 0.047 g/ml (under Eq. (2)). When microglia cells are activated, they become either of M 1 or M 2 phenotype. But peripheral macrophages are initially biased toward phenotype rather than phenotype, since . We assume, in line with this bias toward , that the transition rate from into phenotype by TGF- β is at a smaller rate than the corresponding transition rate for microglias, that is, . We take /day.

Eq. (17)

Activated alveolar macrophages produce TNF- α at rate 4.86×10−3/day [47]. We assume that proinflammatory macrophages produce TNF- α at a larger rate (five fold), taking g/ml.

Eq. (18)

Astrocytes secrete MCP-1 [17–19] but activated anti-inflammatory microglias also secrete MCP-1. We assume that the production rate by astrocytes in larger than that by M 2, and take . MCP-1 concentration in initial stages of AD is 750 pg/ml [98]. Using the steady state equation

with P=6×10−9 g/ml and d P=1.73/day [74], we get /day and λ PA=6×10−8/day [47].

Since A is increasing in time, also P is increasing in time. Hence the steady state assumption needs to be revised. We do it by increasing λ PA and by a factor 1.1, taking /day, and λ PA=6.6×10−8/day.

Acknowledgements

The authors have been supported by the Mathematical Biosciences Institute and the National Science Foundation under Grant DMS 0931642.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

WH and AF developed and simulated the model, and wrote the final manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Wenrui Hao, Email: hao.50@mbi.osu.edu.

Avner Friedman, Email: afriedman@math.osu.edu.

References

- 1.Gatz M, Reynolds CA, Fratiglioni L, Johansson B, Mortimer JA, Berg S, Fiske A, Pedersen NL. Role of genes and environments for explaining Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2006;63(2):168–74. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson RS, Barral S, Lee JH, Leurgans SE, Foroud TM, Sweet RA, Graff-Radford N, Bird TD, Mayeux R, Bennett DA. Heritability of different forms of memory in the Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Family Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;23(2):249–55. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.alzheimers, n.: 2015 Alzheimer’s Statistics. 2016. http://www.alzheimers.net/resources/alzheimers-statistics/. Accessed 1 Sept 2016.

- 4.Liu Z, Li P, Wu J, Yi W, Ping L, Xinxin H, et al.The Cascade of Oxidative Stress and Tau Protein Autophagic Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dis Challenges Future. 2015;2. doi:10.5772/59980.

- 5.Seeman P, Seeman N. Alzheimer’s disease: beta-amyloid plaque formation in human brain. Synapse. 2011;65(12):1289–97. doi: 10.1002/syn.20957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kremer A, Louis JV, Jaworski T, Van Leuven F. GSK3 and Alzheimer’s Disease: Facts and Fiction. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4:17. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloom GS. Amyloid-beta and tau: the trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(4):505–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.5847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mondragon-Rodriguez S, Perry G, Zhu X, Boehm J. Amyloid Beta and tau proteins as therapeutic targets for Alzheimer’s disease treatment: rethinking the current strategy. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:630182. doi: 10.1155/2012/630182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wray S, Noble W. Linking amyloid and tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: the role of membrane cholesterol in Abeta-mediated tau toxicity. J Neurosci. 2009;29(31):9665–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2234-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mokhtar SH, Bakhuraysah MM, Cram DS, Petratos S. The Beta-amyloid protein of Alzheimer’s disease: communication breakdown by modifying the neuronal cytoskeleton. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;2013:910502. doi: 10.1155/2013/910502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joshi P, Turola E, Ruiz A, Bergami A, Libera DD, Benussi L, et. al Microglia convert aggregated amyloid-beta into neurotoxic forms through the shedding of microvesicles. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21(4):582–93. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theriault P, ElAli A, Rivest S. The dynamics of monocytes and microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0125-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Calignon A, Polydoro M, Suarez-Calvet M, William C, Adamowicz DH, Kopeikina KJ, et al. Propagation of tau pathology in a model of early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2012;73(4):685–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garwood CJ, Pooler AM, Atherton J, Hanger DP, Noble W. Astrocytes are important mediators of Abeta-induced neurotoxicity and tau phosphorylation in primary culture. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:167. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morales I, Guzman-Martinez L, Cerda-Troncoso C, Farias GA, Maccioni RB. Neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. A rational framework for the search of novel therapeutic approaches. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:112. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao J, O’Connor T, Vassar R. The contribution of activated astrocytes to A beta production: implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:150. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hohsfield LA, Humpel C. Migration of blood cells to beta-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Gerontol. 2015;65:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li C, Zhao R, Gao K, Wei Z, Yin MY, Lau LT, Chui D, Yu AC. Astrocytes: implications for neuroinflammatory pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8(1):67–80. doi: 10.2174/156720511794604543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porcellini E, Ianni M, Carbone I, Franceschi M, Licastro F. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 promoter polymorphism and plasma levels in alzheimer’s disease. Immun Ageing. 2013;10(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang WY, Tan MS, Yu JT, Tan L. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3(10):136. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.03.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai AY, McLaurin J. Clearance of amyloid-beta peptides by microglia and macrophages: the issue of what, when and where. Future Neurol. 2012;7(2):165–76. doi: 10.2217/fnl.12.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhaskar K, Maphis N, Xu G, Varvel NH, Kokiko-Cochran ON, Weick JP. et al. Microglial derived tumor necrosis factor-alpha drives Alzheimer’s disease-related neuronal cell cycle events. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;62:273–85. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma V, Thakur V, Singh S, Guleria R. Tumor Necrosis Factor and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Cause and Consequence Relationship. Klinik Psik Bull Clin Psyc. 2012;22:86–97. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boutajangout A, Sigurdsson EM, Krishnamurthy PK. Tau as a therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8(6):666–77. doi: 10.2174/156720511796717195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong-Qi Y, Zhi-Kun S, Sheng-Di C. Current advances in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: focused on considerations targeting Abeta and tau. Transl Neurodegener. 2012;1(1):21. doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lansdall C. An effective treatment for Alzheimer’s disease must consider both amyloid and tau. Biosci Horizons. 2014;7. doi:10.1093/biohorizons/hzu002.

- 27.Wischik CM, Harrington CR, Storey JM. Tau-aggregation inhibitor therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88(4):529–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee MH, Lin SR, Chang JY, Schultz L, Heath J, Hsu LJ, Kuo YM, Hong Q, Chiang MF, Gong CX, Sze CI, Chang NS. TGF-beta induces TIAF1 self-aggregation via type II receptor-independent signaling that leads to generation of amyloid beta plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:110. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chao CC, Hu S, Frey WH, Ala TA, Tourtellotte WW, Peterson PK. Transforming growth factor beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1994;1(1):109–10. doi: 10.1128/cdli.1.1.109-110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen JH, Ke KF, Lu JH, Qiu YH, Peng YP. Protection of TGF-beta against neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in Abeta1–42-induced Alzheimer’s disease model rats. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):0116549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das P, Golde T. Dysfunction of TGF-beta signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(11):2855–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI30284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Bernhardi R, Cornejo F, Parada GE, Eugenin J. Role of TGF beta signaling in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:426. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wyss-Coray T. Tgf-Beta pathway as a potential target in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3(3):191–5. doi: 10.2174/156720506777632916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wyss-Coray T, Lin C, Yan F, Yu GQ, Rohde M, McConlogue L, Masliah E, Mucke L. TGF-beta1 promotes microglial amyloid-beta clearance and reduces plaque burden in transgenic mice. Nat Med. 2001;7(5):612–8. doi: 10.1038/87945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Town T, Laouar Y, Pittenger C, Mori T, Szekely CA, Tan J, et al. Blocking TGF-beta-Smad2/3 innate immune signaling mitigates Alzheimer-like pathology. Nat Med. 2008;14(6):681–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cochran JN, Hall AM, Roberson ED. The dendritic hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. Brain Res Bull. 2014;103:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dorostkar MM, Zou C, Blazquez-Llorca L, Herms J. Analyzing dendritic spine pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: problems and opportunities. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130(1):1–19. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1449-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klyubin I, Cullen WK, Hu NW, Rowan MJ. Alzheimer’s disease Abeta assemblies mediating rapid disruption of synaptic plasticity and memory. Mol Brain. 2012;5:25. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-5-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koffie RM, Hyman BT, Spires-Jones TL. Alzheimer’s disease: synapses gone cold. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6(1):63. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Craft DL, Wein LM, Selkoe DJ. A mathematical model of the impact of novel treatments on the A beta burden in the Alzheimer’s brain, CSF and plasma. Bull Math Biol. 2002;64(5):1011–31. doi: 10.1006/bulm.2002.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bertsch M, Franchi B, Marcello N, Tesi MC, Tosin A. Alzheimer’s disease: a mathematical model for onset and progression. Math Med Biol. 2016. doi:10.1093/imammb/dqw003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Helal M, Hingant E, Pujo-Menjouet L, Webb GF. Alzheimer’s disease: analysis of a mathematical model incorporating the role of prions. J Math Biol. 2014;69(5):1207–35. doi: 10.1007/s00285-013-0732-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Puri IK, Li L. Mathematical modeling for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):15176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lao A, Schmidt V, Schmitz Y, Willnow TE, Wolkenhauer O. Multi-compartmental modeling of SORLA’s influence on amyloidogenic processing in Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Syst Biol. 2012;6:74. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-6-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt V, Baum K, Lao A, Rateitschak K, Schmitz Y, Teichmann A, et al. Quantitative modelling of amyloidogenic processing and its influence by SORLA in Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO J. 2012;31(1):187–200. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamza T, Barnett JB, Li B. Interleukin 12 a key immunoregulatory cytokine in infection applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11(3):789–806. doi: 10.3390/ijms11030789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hao W, Crouser ED, Friedman A. Mathematical model of sarcoidosis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(45):16065–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417789111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sokolowski JD, Mandell JW. Phagocytic clearance in neurodegeneration. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(4):1416–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(2):101–12. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waters J. The concentration of soluble extracellular amyloid-beta protein in acute brain slices from CRND8 mice. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):15709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muller S, Ronfani L, Bianchi ME. Regulated expression and subcellular localization of HMGB1, a chromatin protein with a cytokine function. J Intern Med. 2004;255(3):332–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2003.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao HM, Zhou H, Zhang F, Wilson BC, Kam W, Hong JS. HMGB1 acts on microglia Mac1 to mediate chronic neuroinflammation that drives progressive neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2011;31(3):1081–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3732-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lotze MT, Tracey KJ. High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1): nuclear weapon in the immune arsenal. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(4):331–42. doi: 10.1038/nri1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zou JY, Crews FT. Release of neuronal HMGB1 by ethanol through decreased HDAC activity activates brain neuroimmune signaling. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):87915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Savchenko VL, McKanna JA, Nikonenko IR, Skibo GG. Microglia and astrocytes in the adult rat brain: comparative immunocytochemical analysis demonstrates the efficacy of lipocortin 1 immunoreactivity. Neuroscience. 2000;96(1):195–203. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hao W, Rovin BH, Friedman A. Mathematical model of renal interstitial fibrosis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(39):14193–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413970111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roher AE, Esh CL, Kokjohn TA, Castano EM, Van Vickle GD, Kalback WM, et al. Amyloid beta peptides in human plasma and tissues and their significance for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(1):18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Furman JL, Sama DM, Gant JC, Beckett TL, Murphy MP, Bachstetter AD, Van Eldik LJ, Norris CM. Targeting astrocytes ameliorates neurologic changes in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2012;32(46):16129–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2323-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tobinick E, Gross H, Weinberger A, Cohen H. TNF-alpha modulation for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a 6-month pilot study. MedGenMed. 2006;8(2):25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Butchart J, Brook L, Hopkins V, Teeling J, Puntener U, Culliford D, et al. Etanercept in Alzheimer disease: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Neurology. 2015;84(21):2161–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Piazza F, Winblad B. Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities (ARIA) in Immunotherapy Trials for Alzheimer’s Disease: Need for Prognostic Biomarkers? J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52(2):417–20. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karran E, Hardy J. A critique of the drug discovery and phase 3 clinical programs targeting the amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(2):185–205. doi: 10.1002/ana.24188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patel KR. Biogen’s aducanumab raises hope that Alzheimer’s can be treated at its source. Manag Care. 2015;24(6):19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reardon S. Antibody drugs for Alzheimer’s show glimmers of promise. Nature. 2015;523(7562):509–10. doi: 10.1038/nature.2015.18031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ge S, Shrestha B, Paul D, Keating C, Cone R, Guglielmotti A, Pachter JS. The CCL2 synthesis inhibitor bindarit targets cells of the neurovascular unit, and suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:171. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Severini C, Passeri PP, Ciotti M, Florenzano F, Possenti R, Zona C, et al. Bindarit, inhibitor of CCL2 synthesis, protects neurons against amyloid-??-induced toxicity. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;38(2):281–93. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li JY, Ren YP, Yuan Y, Ji SM, Zhou SP, Wang LJ, Mou ZZ, Li L, Lu W, Zhou TY. Preclinical PK/PD model for combined administration of erlotinib and sunitinib in the treatment of A549 human NSCLC xenograft mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(7):930–40. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nielsen EI, Cars O, Friberg LE. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) indices of antibiotics predicted by a semimechanistic PKPD model: a step toward model-based dose optimization. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(10):4619–30. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00182-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yuan Y, Zhou X, Ren Y, Zhou S, Wang L, Ji S, Hua M, Li L, Lu W, Zhou T. Semi-Mechanism-Based Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Model for the Combination Use of Dexamethasone and Gemcitabine in Breast Cancer. J Pharm Sci. 2015;104(12):4399–408. doi: 10.1002/jps.24629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bloom GS. Amyloid-beta and tau: the trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(4):505–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.5847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marino S, Hogue IB, Ray CJ, Kirschner DE. A methodology for performing global uncertainty and sensitivity analysis in systems biology. J Theor Biol. 2008;254(1):178–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Collins-Praino LE, Francis YI, Griffith EY, Wiegman AF, Urbach J, Lawton A, Honig LS, Cortes E, Vonsattel JP, Canoll PD, Goldman JE, Brickman AM. Soluble amyloid beta levels are elevated in the white matter of Alzheimer’s patients, independent of cortical plaque severity. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:83. doi: 10.1186/s40478-014-0083-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mohs RC, Haroutunian V. Chapter 82: Alzheimer Disease: From Earliest Symptoms to End Stage. Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation of Progress. 1999;8(2):1189–1197. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hao W, Friedman A. The LDL-HDL profile determines the risk of atherosclerosis: a mathematical model. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):90497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Young ME, Carroad PA, Bell RL. Estimation of Diffusion Coefficients of Proteins. Biot Bioe. 1980;22(5):947–55. doi: 10.1002/bit.260220504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen D, Roda JM, Marsh CB, Eubank TD, Friedman A. Hypoxia inducible factors-mediated inhibition of cancer by GM-CSF: a mathematical model. Bull Math Biol. 2012;74(11):2752–77. doi: 10.1007/s11538-012-9776-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yokochi S, Hashimoto H, Ishiwata Y, Shimokawa H, Haino M, Terashima Y, Matsushima K. An anti-inflammatory drug, propagermanium, may target GPI-anchored proteins associated with an MCP-1 receptor, CCR2. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2001;21(6):389–98. doi: 10.1089/107999001750277862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dubois CM, Laprise MH, Blanchette F, Gentry LE, Leduc R. Processing of transforming growth factor beta 1 precursor by human furin convertase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(18):10618–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stepanets OV, Chichasova NV, Nasonova MB, Samsonov MIU, Nasonov EL. [Soluble receptors of TNF-alpha with molecular mass 55 kDa in rheumatoid arthritis: clinical role] Klin Med (Mosk) 2003;81(4):42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bonaldi T, Talamo F, Scaffidi P, Ferrera D, Porto A, Bachi A, Rubartelli A, Agresti A, Bianchi ME. Monocytic cells hyperacetylate chromatin protein HMGB1 to redirect it towards secretion. EMBO J. 2003;22(20):5551–60. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ahmed M, Davis J, Aucoin D, Sato T, Ahuja S, Aimoto S, Elliott JI, Van Nostrand WE, Smith SO. Structural conversion of neurotoxic amyloid-beta(1–42) oligomers to fibrils. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(5):561–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saido T, Leissring MA. Proteolytic degradation of amyloid beta-protein. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(6):006379. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cragg BG. The density of synapses and neurons in normal, mentally defective ageing human brains. Brain. 1975;98(1):81–90. doi: 10.1093/brain/98.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gate D, Rezai-Zadeh K, Jodry D, Rentsendorj A, Town T. Macrophages in Alzheimer’s disease: the blood-borne identity. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2010;117(8):961–70. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0422-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heppner FL, Ransohoff RM, Becher B. Immune attack: the role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(6):358–72. doi: 10.1038/nrn3880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Herculano-Houzel S. The human brain in numbers: a linearly scaled-up primate brain. Front Hum Neurosci. 2009;3:31. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.031.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Herculano-Houzel S. The glia/neuron ratio: how it varies uniformly across brain structures and species and what that means for brain physiology and evolution. Glia. 2014;62(9):1377–91. doi: 10.1002/glia.22683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Poppek D, Keck S, Ermak G, Jung T, Stolzing A, Ullrich O, Davies KJ, Grune T. Phosphorylation inhibits turnover of the tau protein by the proteasome: influence of RCAN1 and oxidative stress. Biochem J. 2006;400(3):511–20. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kapaki E, Kilidireas K, Paraskevas GP, Michalopoulou M, Patsouris E. Highly increased CSF tau protein and decreased beta-amyloid (1–42) in sporadic CJD: a discrimination from Alzheimer’s disease? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2001;71(3):401–3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.3.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hao W, Schlesinger LS, Friedman A. Modeling Granulomas in Response to Infection in the Lung. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):0148738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Elson K, Ribeiro RM, Perelson AS, Simmons A, Speck P. The life span of ganglionic glia in murine sensory ganglia estimated by uptake of bromodeoxyuridine. Exp Neurol. 2004;186(1):99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maree AF, Komba M, Finegood DT, Edelstein-Keshet L. A quantitative comparison of rates of phagocytosis and digestion of apoptotic cells by macrophages from normal (BALB/c) and diabetes-prone (NOD) mice. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(1):157–69. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00514.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang J, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. The levels of soluble versus insoluble brain Abeta distinguish Alzheimer’s disease from normal and pathologic aging. Exp Neurol. 1999;158(2):328–37. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhu XD, Chen JS, Zhou F, Liu QC, Chen G, Zhang JM. Relationship between plasma high mobility group box-1 protein levels and clinical outcomes of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:194. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Allette YM, Due MR, Wilson SM, Feldman P, Ripsch MS, Khanna R, White FA. Identification of a functional interaction of HMGB1 with Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-products in a model of neuropathic pain. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;42:169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.06.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rezai-Zadeh K, Gate D, Gowing G, Town T. How to get from here to there: macrophage recruitment in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8(2):156–63. doi: 10.2174/156720511795256017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rezai-Zadeh K, Gate D, Town T. CNS infiltration of peripheral immune cells: D-Day for neurodegenerative disease? J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009;4(4):462–75. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9166-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Westin K, Buchhave P, Nielsen H, Minthon L, Janciauskiene S, Hansson O. CCL2 is associated with a faster rate of cognitive decline during early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1):30525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hao W, Marsh C, Friedman A. A Mathematical Model of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):0135097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.