Abstract

Purpose

To characterize disease burden and medication usage in rural and urban adults aged ≥ 85 years.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of 5 years of longitudinal data starting in the year 2000 from 3 brain-aging studies. Cohorts consisted of community-dwelling adults: one rural cohort, The Klamath Exceptional Aging Project (KEAP), was compared to 2 urban cohorts, the Oregon Brain Aging Study (OBAS) and the Dementia Prevention study (DPS). In this analysis, 121 participants were included from OBAS/DPS and 175 participants were included from KEAP. Eligibility was determined based on age ≥ 85 years and having at least 2 follow-up visits after the year 2000. Disease burden was measured by the Modified Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (MCIRS), with higher values representing more disease. Medication usage was measured by the estimated mean number of medications used by each cohort.

Findings

Rural participants had significantly higher disease burden as measured by MCIRS, 23.0 (95% CI: 22.3–23.6), than urban participants, 21.0 (95% CI: 20.2–21.7), at baseline. The rate of disease accumulation was a 0.2 increase in MCIRS per year (95% CI: 0.05–0.34) in the rural population. Rural participants used a higher mean number of medications, 5.5 (95% CI: 4.8–6.1), than urban participants, 3.7 (95% CI: 3.1–4.2), at baseline (P < .0001).

Conclusions

These data suggest that rural and urban Oregonians aged ≥ 85 years may differ by disease burden and medication usage. Future research should identify opportunities to improve health care for older adults.

Keywords: epidemiology, geriatrics, health disparities, pharmacy, utilization of health services, Older, Rural, Drugs, Medications, Multimorbidity

Access to health services and appropriate treatments for chronic disease is vital for older adults to maintain health and independence. Octogenarians and nonagenarians, especially with high disease burden, have significant health care needs but are largely understudied.1 There is growing evidence that disparities in disease burden are particularly pronounced among older adults living in rural areas.2,3

Rural and urban residents are distinct in terms of social and physical health, and they vary in access to health care services.4,5 This may be clinically important as some research suggests worse health outcomes among rural populations.6–10 Understanding the differences of chronic diseases and medication utilization in older adults of rural areas is important to understand gaps in our health care system and in meeting this populations’ needs.

Detailed longitudinal studies of rural individuals, aged 85 years and older, and how they use medications are also lacking. Research on drug utilization in rural populations of all ages is mixed. A recent meta-analysis of 9 ambulatory-care-based studies in adults of all ages found no difference in cardiovascular medication utilization between urban and rural populations.11

Older adults in general, however, are known to use more medications, especially those aged 85 years and older.12,13 Therefore, rural regions may ensconce isolated older adults who are less healthy and managing complex medication regimens, but there are few studies in rural, very old adults. Not only does the rural Oregon population comprise a greater proportion of older adults (18.6%) than the urban Oregon population (13.1%),14 but the proportion of older adults in rural areas is expected grow and age as the overall population ages.15 The data used in this study is unique; prescription and over-the-counter medication information was collected by investigators every 6 months for at least 5 years.

The use of many medications, ie, polypharmacy, may be especially risky for those in their eighth or ninth decade.16,17 The physiologic process of aging places older adults at an increased risk for adverse drug events, a culprit for otherwise preventable emergency department visits and hospitalizations.18 Therefore, even one extra medication on an older adult’s regimen could have a large impact on their overall well-being, especially for those in rural populations who have greater difficulty accessing emergency services.19

The purpose of this study was to quantify and characterize differences in disease burden and medication usage between rural and urban adults aged 85 and older. Because this population experiences increased frailty, seemingly small differences in health and medication utilization could translate to decreased lifespan in this population.

Methods

Participants and Setting

This study is a secondary, longitudinal analysis of data from 3 cohorts of older adults in Oregon, 1 rural and 2 urban. All cohorts were managed by the National Institute on Aging’s Layton Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) in Portland, Oregon. All studies were initially designed to examine brain aging. Study subjects in all cohorts were given comprehensive examinations in their homes or at a clinic every 6 months by a geriatric research nurse, staff neurologist, or neuropsychologist, for clinical and cognitive evaluation using a standard protocol.20 Evaluation included a collateral interview with one person who had close contact with each subject. Self-reported conditions were verified with the subject’s medical chart. Medication usage was obtained by interview and verified at a home or clinic visit where containers were seen by researchers. Functional impairment was assessed using a modified Older Americans Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment and Questionnaire21 that assessed Activities of Daily Living (ADL)22 and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL).23 Cognitive function was summarized using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)24 and dementia was staged with the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR).25

Urban Participants

The Oregon Brain Aging Study (OBAS) was initiated in 1989 and consisted of community-living, functionally independent older subjects.26 Subjects were recruited through retirement facilities, senior fairs, flyers, and via word of mouth in the community. Individuals who met initial inclusion criteria were age 65 or older and had no functional impairment defined by the ADL scale, no comorbid illnesses noted in their medical record, a baseline MMSE score greater than 23, and no exhibition of depression by screening with the Geriatric Depression Scale.27 Between 1989 and 2005, a total of 305 subjects were enrolled in OBAS.

In the Dementia Prevention Study (DPS), 134 adults aged 85 years and older were recruited by mailed letters sent to age-appropriate persons identified by the Department of Motor Vehicles and Oregon Voter Registration.28 DPS was a 4-year, placebo-controlled trial of gingko biloba and its effects on mild cognitive impairment. DPS was initiated in the year 2000. In the year 2004 the DPS randomized clinical trial ended and DPS participants were enrolled in OBAS as an enrichment cohort. Participants in DPS/OBAS were aged ≥ 85, had no subjective memory complaints and were free from depressive symptoms. The DPS cohort was considered to be of average health for their age, meaning that they had stable chronic diseases such as hypertension and heart disease.

This definition of urban used is consistent with that used by the US Census and the United States Department of Agriculture.29,30

Rural Participants

The Klamath Exceptional Aging Project (KEAP) is a longitudinal study of adults aged 85 and older who live in the Klamath Basin watershed, a rural area in south-central Oregon and Northern California.31 The region includes the county seat, Klamath Falls, Oregon; 20 small towns; and a large frontier area with a population density of under 5 persons per square mile. This definition of rural is consistent with that used by the United States Department of Agriculture.29 KEAP started in 1999 and enrolled 424 community-living adults 85 years and older. KEAP is a population-based study and participants were allowed to have stable chronic diseases such as hypertension and heart disease at baseline. KEAP participants may have had problems with mild cognitive impairment defined by a CDR of 0.5, but they could have no physician diagnosis of dementia. Participants entered the study through physician referral, caregiver referral, self-referral from advertising, and targeted recruitment drives.

Summary of Study Designs

KEAP, OBAS, and DPS are all Oregon-based studies on brain aging in older adults. Standardized measurements in each of these cohorts were taken every 6 months by a trained researcher. Participants were only eligible if they were free from dementia. Participants in all 3 studies were followed longitudinally, until death. Major differences of these studies include region (rural vs urban) and study initiation date: OBAS in 1989, KEAP in 1999, and DPS in 2000. Another difference is the initial inclusion criteria: OBAS participants were free from chronic diseases upon enrollment (in 1989); KEAP and DPS participants were of “average health” and allowed to have “stable chronic conditions” (in 1999 and 2000, respectively).

All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at OHSU and informed consent was obtained from all participants. This secondary analysis of de-identified data is not considered to be human-subject research and was determined to be exempt from human subject research by the OHSU IRB.

Our study analyzed data from the first point in time when all 3 cohorts had follow-up data, the year 2000. The following inclusion criteria for this analysis was used for all 3 studies: 1) participated in at least 2 clinic visits after the year 2000; 2) the first eligible visit was when the participant was 84.5 years or older, this was considered the “baseline visit”; 3) because this is a longitudinal analysis, the participants must have had at least 2 measurements for the outcomes of interest.

Outcome Measures

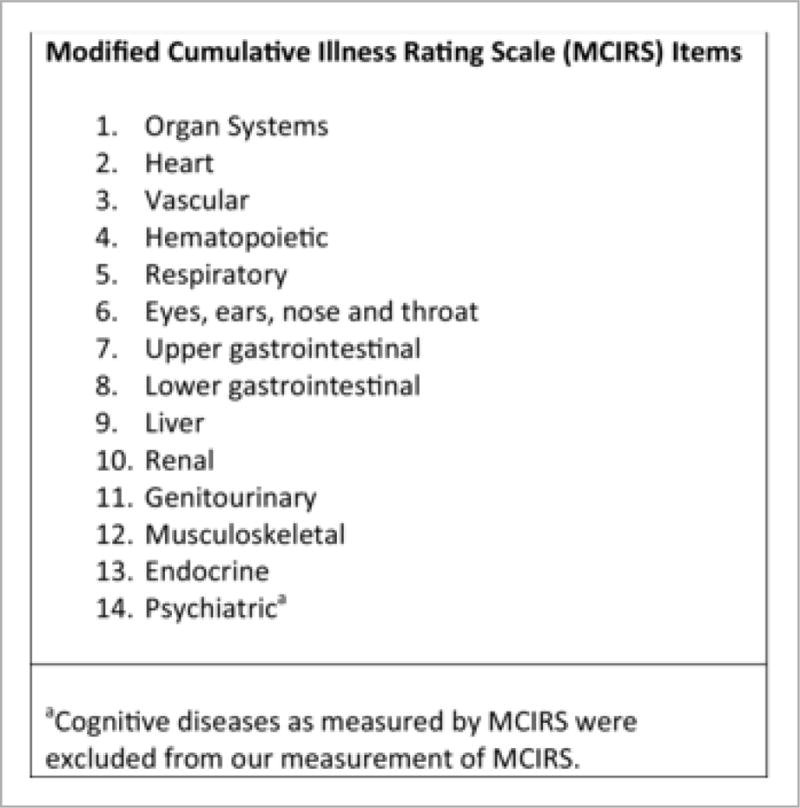

We defined chronic disease burden using the Modified Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (MCIRS), a validated indicator of health status and predictive of 18-month mortality in older persons.32 MCIRS provides a numeric rating for burden of chronic illness. MCIRS scores can range from 13 (disease-free) to 65 (highest measure of disease burden). Studies have shown that subjects in the highest MCIRS quartile are at significantly greater risk of death.32,33 MCIRS assigns scores to 14 items representing individual body systems (see Figure 1). Diseases of the central nervous system, as measured by MCIRS, were excluded from the original measurement because all of these studies were designed to detect cognitive disease as an outcome. Baseline and subsequent MCIRS measurements were found to be normally distributed.

Figure 1.

Fourteen Items that Comprise the MCIRS.

Medication usage was defined by self-report; it was confirmed with patients’ bringing their containers to clinic or by researchers reviewing containers at a home visit. To calculate the number of medications used, the authors coded and standardized medications with the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification codes.34 Combination products were linked to their individual components. Non-prescriptive medications, including herbal, alternative, and over-the-counter (OTC) medicines, were also coded. Medications were assigned to several therapeutic classes. Medications were assigned to 3 large classes: prescriptive medications, over-the-counter agents, and Beers Criteria agents. The Beers Criteria is a list of agents considered to be potentially inappropriate medications in older adults.35

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics at baseline were compared between urban and rural cohorts using t-tests for continuous normally distributed variables, Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test for continuous non-normally distributed variables, and Chi-Square test for categorical variables.

Longitudinal linear mixed-effects regression models were used to determine the association between rural status and MCIRS over time. Models were fit, with and without adjusting for demographic differences between the 2 populations. Longitudinal models were adjusted for baseline MCIRS values. Candidate covariates were selected a priori based on literature searches and clinical expertise of authors. Interactions between sex, cognitive impairment and level of education were tested using the type III F-statistic.

Longitudinal mixed-effect Poisson regression models with a logit link were used to determine the association between rural status and number of medications used over time. Other longitudinal trends were explored, ie, squared and quadratic equations. Separate models were developed for each of the following classes of medications: prescriptive medications, over-the-counter agents, and Beers Criteria agents. Candidate covariates were selected a priori based on literature searches and clinical expertise of authors.

Simple linear regression models were used to determine the association between disease burden (MCIRS) and number of medications used at baseline. Linear regressions were done for rural and urban cohorts separately.

Longitudinal mixed-effects regression models with a binomial link were used to estimate the proportion of each therapeutic class of medications used in the rural and urban populations. The outcome for this model was the estimated number of medications of a therapeutic class divided by the estimated number of prescriptive medications or OTC agents where appropriate. Unadjusted models were used due to some medication classes being infrequently prescribed.

For all analyses, subjects were followed longitudinally for 5 years from baseline because less than 30% of participants survived after that point in time. Analyses were completed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

The total number of eligible participants aged 85 and older in our analytic cohort was 121 out of 296 recruited (41%) from the OBAS/DPS and 175 (59%) from the KEAP cohort. Of the 121 participants in OBAS/DPS, 36 participants (30%) had been participating in OBAS for an average of 9.8 ± 6.0 years before reaching baseline eligibility for our analysis. Eighty-five participants (70%) were part of the DPS cohort and OBAS enrichment cohort.

After the year 2000, rural participants survived for a median of 3.5 years. Urban participants survived for a median of 7.1 years. Baseline participant characteristics and bivariate associations of the characteristics between rural-urban groups are presented in Table 1. Compared with their urban counterparts, rural participants had significantly less education (P < .001). In addition, a statistically greater proportion of rural participants had impairments in cognition, ADL, IADL, and the following chronic diseases: diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, arrhythmia, and heart failure. Rural participants had statistically lower MMSE scores.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Urban and Rural Participants

| Characteristic | Urban (N =121) | Rural (N=175) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Median (IQR) | 86.3 years (±2.5) | 86.0 years (±2.6) | .05 |

| Years of Education, Mean (±SD) | 14.1 Years (±2.5) | 12.3 years (±3.1) | <.001 |

| Female (%) | 78 (64.4) | 112 (64.0) | .93 |

| White race (%) | 117 (96.7) | 173 (98.8) | .19 |

| Presently Married (%) | 31 (25.6) | 47 (26.8) | .81 |

| Participants with ADL impairment > 3 (%) | 1 (0.8) | 16 (9.1) | .003 |

| Participants with IADL impairment > 3 (%) | 1 (0.8) | 19 (10.8) | .007 |

| MMSE, Median (IQR) | 29 (1) | 27 (3) | <.001 |

| Cognitive Impairment (%) | 7 (5.8) | 65 (37.1) | <.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 80 (66.1) | 117 (66.8) | .47 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (±SD) | 149.1 (±24.5) | 142.1 (±18.4) | .01 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (±SD) | 70.0 (±10.4) | 71.7 (±9.18) | .14 |

| Depression (%) | 38 (31.4) | 43 (24.6) | .19 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (%) | 35 (28.9) | 62 (35.4) | .24 |

| Diabetes (%) | 10 (8.3) | 27 (15.4) | .07 |

| Stroke (%) | 14 (11.6) | 10 (5.7) | .07 |

| TIA (%) | 2 (1.6) | 14 (8.0) | .017 |

| Arrhythmia (%) | 23 (19.0) | 85 (48.6) | <.001 |

| Myocardial Infarction (%) | 15 (12.4) | 26 (14.8) | .55 |

| Heart failure (%) | 17 (14.0) | 52 (29.1) | .003 |

Disease Burden

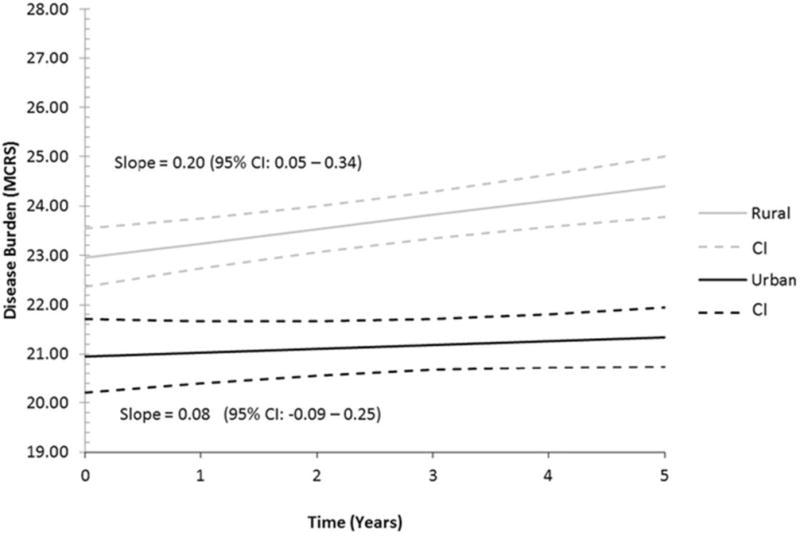

In our analysis of rural status on the burden of disease (Table 2), adjusted baseline MCIRS was 23.0 (95% CI: 22.3–23.6) for rural participants and 21.0 (95% CI: 20.2–21.7) for urban participants. Rural Oregonians were found to have higher disease burden as measured by MCIRS at baseline and at annual visits over a 5-year period compared to their urban counterparts. Results from the unadjusted and fully adjusted models were similar and are displayed in Table 2. Figure 2 shows the longitudinal trend of accumulating disease burden for both populations. The annual rate of disease accumulation in urban participants was not statistically significant at 0.08 MIRCS units per year (95% CI: −0.09–0.25). The rural population accumulated disease burden at a rate of 0.2 MCIRS units per year (95% CI: 0.05–0.34), a statistically significant increase in disease burden over time.

Table 2.

Disease Burden as Measured by MCIRS for Urban and Rural Older Adults in Oregon

| Location | Baseline Visit | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Slope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Unadjusted Model | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Rural MCIRS (95% CI) |

22.9 (22.5 – 23.5) |

23.4 (22.9 – 23.8) |

23.7 (23.3 – 24.2) |

24.1 (23.6 – 24.5) |

24.4 (23.9 – 24.9) |

24.7 (24.2 – 25.4) |

0.18 (P = .02)* |

|

Urban MCIRS (95% CI) |

20.6 (19.9 – 21.1) |

20.7 (20.2 – 21.3) |

20.9 (20.4 – 21.5) |

21.1 (20.6 – 21.6) |

21.3 (20.8 – 21.8) |

21.5 (20.9 – 22.0) |

0.18 (P = .003)* |

|

| |||||||

| Model 2: Fully Adjusted Model | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Rural MCIRS (95% CI) |

23.0 (22.3 – 23.6) |

23.2 (22.7 – 23.8) |

23.5 (23.0 – 24.0) |

23.8 (23.3 – 24.3) |

24.0 (23.5 – 24.6) |

24.3 (23.7 – 25.0) |

0.20 (P = .008)* |

|

Urban MCIRS (95% CI) |

21.0 (20.2 – 21.7) |

21.0 (20.4 – 21.7) |

21.1 (20.6 – 21.7) |

21.2 (20.7 – 21.7) |

21.3 (20.7 – 21.8) |

21.3 (20.7 – 21.9) |

0.08 (P = .38)* |

CI, 95% confidence interval; MCIRS, modified cumulative index rating scale, normal range is between 5 and 65. Slope estimated from a longitudinal mixed-effect linear model. Adjusted for age, sex, education, marital status, ethnicity, mini-mental status exam score, activities of daily living scores, and instrumental activities of daily living scores. Cognitive diseases as measured by MCIRS were excluded from our measurement of MCIRS.

P values for the comparison of the longitudinal slope to a slope of zero.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal Trends of Disease Burden as Measured by MCIRS for Urban and Rural Oregonians. Adjusted for age, sex, education, marital status, ethnicity, MMSE, ADL, and IADL scores. Cognitive diseases as measured by MCIRS were excluded from our measurement of MCIRS.

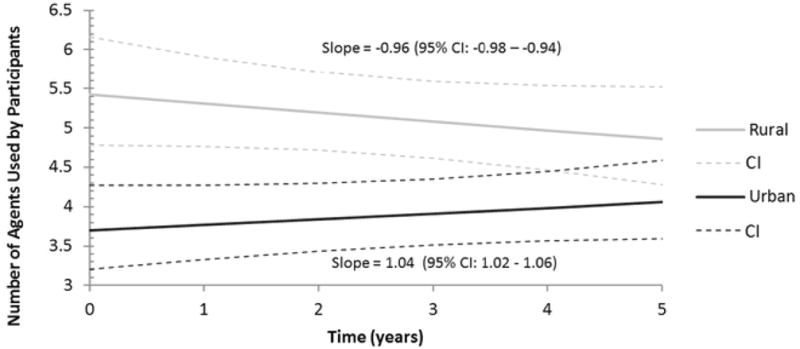

Prescription Medications

Rural participants were found to use an estimated average of 5.5 (95% CI: 4.8–6.1) prescription medications at baseline. Urban participants used an estimated average of 3.7 (95% CI: 3.1–4.2) medications. The change in medication usage trended in opposite directions for the 2 populations (P < .001), with urban participants increasing and rural participants decreasing the mean number of medications used. The urban population increased prescription medication use at a rate of approximately 1 new mediation over the 5-year follow-up period of the study: 1.04 (95% CI: 1.01–1.07) medications. Participants of the rural population were estimated to stop use of about 1 prescription medication over 5 years: −0.96 (95% CI: −0.98 to −0.94) medications (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Estimated Number of Medications for Rural and Urban Participants.

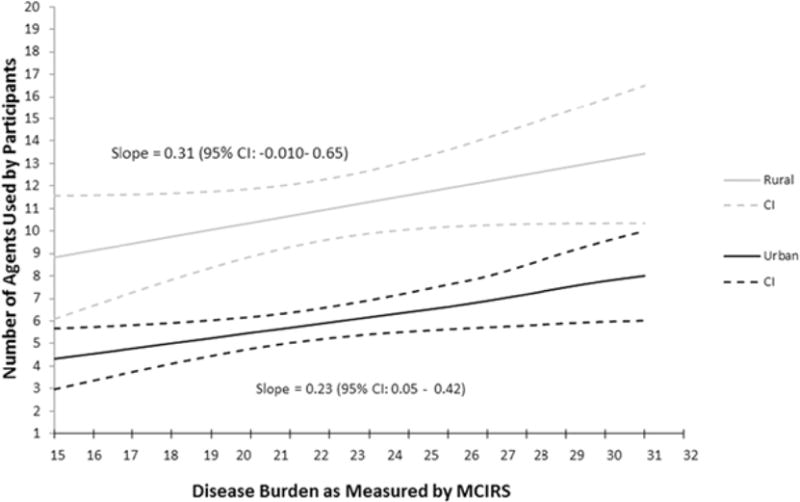

In Figure 4, the estimated number of prescription medications was plotted against MCIRS for the rural and urban cohorts. It was found that rural participants with similar disease burden used more drugs than their urban counterparts. The urban cohort was found to have a significant upward slope, with number of prescription medications increasing as disease burden increased (P = .02). The rural population had a positive slope that trended toward significance (P = .08), but there was more variability in this observation.

Figure 4.

Estimated Number of Medications for Rural and Urban Participants as Predicted by Diseases Burden.

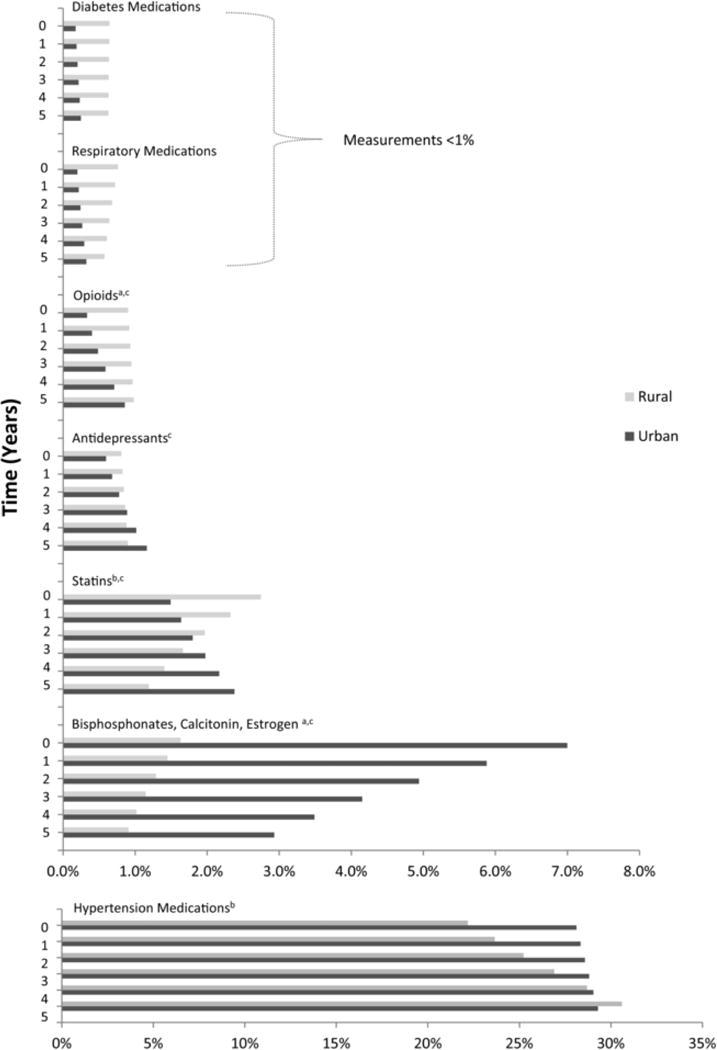

The proportions of prescription medications used, by class, are displayed in Figure 5. Antihypertensive medications were the most commonly prescribed class of medications at baseline: 22% (95% CI: 18.3%–27.2%) in rural participants and 28% (95% CI: 22.3%–36.1%) of prescription medications in urban participants. Prescription medications used to aid bone mineralization (bisphosphonates, calcitonin, estrogen) were used more in the urban population at a proportion of 6.8% (95% CI: 4.7%–10.4%) versus the rural population, which was estimated at 1.6% (95% CI: 1.06%–2.5%) at baseline. Opioid medications were prescribed at a relatively low proportion in both populations, but more were used in the rural population at baseline (P = .03).

Figure 5.

Proportion of Prescription Medications Used by Class, Over Time, for Rural and Urban Participants.

a Statistically significant difference between the rural and urban populations at baseline (P < .05).

b Statistically significant slope for change in use of medications for rural population (P < .05).

c Statistically significant slope for change in use of medications for urban population (P < .05).

Figure 5 also displays patterns of medication utilization over the 5 follow-up years. There was a significant increase in the proportion of estimated number of antihypertensive medications in the rural population over time (P = .006) but not the urban population (P = .05). Use of statin medications significantly increased over time in the urban population but significantly decreased in the rural population. Utilization of bone mineralization agents in the urban population seems to decrease over time. Significant increases in utilization were observed for antidepressants and opioids in the urban population, while no change for these classes were observed for the rural populations.

Over-the-Counter Medications

Analysis of OTC agents suggested no statistical differences between rural and urban participants. Rural participants were found to use an estimated average of 8.8 OTC agents (95% CI: 8.2–9.4) at baseline, and urban participants were found to use an estimated average of 8.9 OTC agents (95% CI: 8.3–9.6) at baseline. Participants of both rural and urban populations are estimated to stop use of approximately 1 OTC agent over the 5-year follow-up period: − 0. 98 agents (95% CI: −0.99 to −0.96).

Vitamins and essential minerals (eg, iron) represented the greatest proportion (approximately 21% for both groups) of OTC agents. Calcium is an essential mineral that is indicated for most older adults sometimes under the guidance of a physician, and it was therefore quantified separately from other OTC vitamins. Calcium represented the smallest proportion, approximately 4%, of OTC agents. No significant changes in use over time were observed for any class of OTC agent.

Beer’s Criteria Agents

The Beer’s Criteria includes agents that are both prescriptive and available over-the-counter. Rural participants were found to use an estimated average of 1.3 Beer’s Criteria agents (95% CI: 1.1–1.5) at baseline. Urban participants were found to use an estimated average of 1.0 Beer’s Criteria agents (95% CI: 0.8–1.2) at baseline. While these are not statistically different from each other, it is of note that the urban population had a significant increase (P = .04) in use of Beer’s Criteria agents over the 5-year follow-up period. At the last follow-up visit the urban population was estimated to use 1.3 Beer’s Criteria agents (95% CI: 1.1–1.5).

Discussion

Our analysis to quantify the disease burden in rural and urban adults aged ≥ 85 years found several differences. We found that the rural cohort had significantly higher disease burden (MCIRS) at every follow-up visit. The rate of disease accumulation in the rural cohort was significant over 5 years of follow-up, while disease accumulation in urban participants was negligible. After adjustment for key demographic characteristics, these findings remained significant. This finding is consistent with other studies that show rural older adults are less healthy than their urban counterparts.36, 37 However, few studies have this large of a population of adults over the age of 85 that were studied in detail from such a remote area. Also, many studies aren’t longitudinal; we found that not only do rural older adults have higher disease burden, they accumulate disease burden at a faster rate than urban older adults. A natural consequence of increased disease is that rural adults have shorter life spans, and this was observed in our study where the median survival time of the rural cohort was 3.5 years and the urban cohort’s median survival time was 7.1 years. These findings are consistent with previous investigations.5–7,9

Explaining how disease burden increases in aging populations, especially rural populations, is complicated by multiple factors. A recent systematic review detailed several longitudinal studies that found the risk factors of chronic diseases were low education, poor socioeconomic status, a history of chronic disease, being female, and older age. Unfortunately, these risk factors are congruent with the characteristics of a typical rural population. In contrast, living with someone and/or having a large social network were 2 protective factors against chronic disease that were identified in this systematic review.37 These protective factors may be more common in an urban or suburban population.

Our analysis to quantify and characterize medication usage in rural and urban adults aged 85 and older found that the rural cohort used significantly more prescription medications at baseline than the urban cohorts. This may be appropriate given that rural individuals had a higher disease burden, but a crude linear regression of MCIRS and number of medications found that rural individuals use more prescription medications, even at the same disease burden as their urban counterparts. Medication use in the rural participants appears to significantly decrease over time. This finding could be explained by clinicians in the Klamath Basin Region simplifying medication regimens for the study participants. This could be beneficial if medications are used judiciously to enhance quality of life and functional status of older adults. An alternative hypothesis is that the finding reflects the shorter median follow-up time in the rural population when compared to the urban population. The differential rate of death could affect the rate of overall medication use in the rural participants, presuming that rural heavy medication users are dying sooner than rural light medication users.

The classes of medications that appeared to contribute to the overall difference between the rural and urban cohorts are likely opioid agents, statins, respiratory agents, anti-diabetic agents, and antidepressants. In contrast, bone mineralizing agents and antihypertensive agents appeared to have more usage in the urban cohorts. While many findings about specific drug classes were not statistically significant in our study and estimates are unadjusted, they could implicate differences in practitioners’ prescribing patterns between the 2 areas. A study by Funkhouser et al38 found that rural location, more than age, sex, specialty, and practicing solo, was the characteristic among physicians that had the strongest association with β-Blocker prescriptions in post-myocardial infarction patients.

There is little information in the literature about how older adults choose and use nonprescription medications, including knowledge about how OTC agent use differs from prescription medication use. Data from an unpublished study of 2003 – 2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found the average number of OTC agents in a population aged 65 years and older to be 3.91.39 In spite of their differences, both rural and urban participants were found to use a large number of OTC agents, including vitamins, minerals, and herbal supplements. OTC agents could be targeted by clinicians to simplify regimens, reduce the risks associated with polypharmacy, and improve overall adherence to medication regimens. More home-based interventions and more oversight of self-treatment are 2 ways that clinicians could ensure community-living, older adults are safely using OTC agents.

The Beer’s Criteria catalogue was used to determine prescription medications and OTC agents that have the potential to cause adverse drug events in older adults due to their pharmacologic properties and the physiologic changes of aging.35 While rural and urban cohorts were found to use about the same number of these medications, a significant increase over time was observed in the urban participants. It is important to note the challenge faced by providers to stay informed of changing prescribing guidelines. There over 60 medications on the 2003 Beer’s List and more than 20 of these medications are new additions that were not included on the previous 1997 version of the list.39

Limitations and Strengths

This study has some limitations. First, it was conducted in a single state, Oregon. However, many states have a similar divide between rural and urban metropolitan areas as observed in this study. Clinicians and researchers may find the trends observed in this study useful and could apply these concepts to their own work. The demographics of Oregon are mostly homogeneous with 97% of all participants being of white race, and thus our findings may not be applicable to diverse populations. Second, this study is observational and there may be residual confounding from factors that were not measured during data collection. Lastly, the rural and urban participants in this study had different initial inclusion criteria as described above. While the inclusion criteria were different, we think these cohorts are similar enough to observe trends in disease burden and drug utilization.

Conversely, this study also has strengths. There was detailed collection of covariates and cognitive measures by trained clinicians and follow-up was frequent, every 6 months. There was virtually no loss to follow-up in any of the 3 cohorts, as subjects were followed until death. These cohorts are composed of very old subjects who are community dwelling, while much of the existing research on populations over the age of 85 is conducted in long-term-care facilities. Therefore these data are unique in depicting the medication utilization of fairly healthy and functional older adults.

Given that our study and previous studies have shown rural populations to have worse health and higher medication utilization, future research is needed in developing feasible interventions to improve the lives of rural older adults. Because older adults are vulnerable to adverse effects of medications, more oversight of prescription, OTC, and herbal therapies is needed to optimize medication regimens in older adults. By increasing access to health care, health education, and oversight from clinicians, older adults of rural areas could be given a better opportunity to lead safer and longer lives.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported in part by the Oregon Tax Check-off Alzheimer’s Research Fund administered by the Layton Aging & Alzheimer’s Disease Center in collaboration with the Oregon Partnership for Alzheimer’s Research.

References

- 1.Patient-centered care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: a stepwise approach from the American Geriatrics Society: American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60:1957–1968. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quandt S, McDonald J, Bell R, Arcury T. Aging research in multi-ethinic rural communities: Gaining entrée through community involvement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1999;14:113–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1006625029655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell RA, Smith SL, Arcury TA, Snively BM, Stafford JM, Quandt SA. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among rural older African Americans, Native Americans, and whites with diabetes. Diabetes care. 2005;28:823–829. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oregon Values and Beliefs Survey: True North. DHM Research and Policy Interactive. 2013 Available at: http://oregonvaluesproject.org/. Accessed.

- 5.Vanderboom CP, Madigan EA. Relationships of rurality, home health care use, and outcomes. Western journal of nursing research. 2008;30:365–378. doi: 10.1177/0193945907303107. discussion 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chevarley FM, Owens PL, Zodet MW, Simpson LA, McCormick MC, Dougherty D. Health care for children and youth in the United States: annual report on patterns of coverage, utilization, quality, and expenditures by a county level of urban influence. Ambulatory pediatrics: the official journal of the Ambulatory Pediatric Association. 2006;6:241–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH, Curtin T, Hart LG. Shortages of medical personnel at community health centers: implications for planned expansion. Jama. 2006;295:1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldwin LM, MacLehose RF, Hart LG, Beaver SK, Every N, Chan L. Quality of care for acute myocardial infarction in rural and urban US hospitals. J Rural Health. 2004;20:99–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hand R, Klemka-Walden L, Inczauskis D. Rural hospital mortality for myocardial infarction in Medicare patients in Illinois. American journal of medical quality. 1996;11:135–141. doi: 10.1177/0885713X9601100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levin KA, Leyland AH. Urban-rural inequalities in ischemic heart disease in Scotland, 1981–1999. Am J Pub Health. 2006;96:145–151. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.051193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy GK, McAlister FA, Weir DL, Tjosvold L, Eurich DT. Cardiovascular medication utilization and adherence among adults living in rural and urban areas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:544. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT. Polypharmacy in elderly patients. The American journal of geriatric pharmacotherapy. 2007;5:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linjakumpu T, Hartikainen S, Klaukka T, Veijola J, Kivela SL, Isoaho R. Use of medications and polypharmacy are increasing among the elderly. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2002;55:809–817. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Census Bureau. Census. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirschner A, Berry EH, Glasgow N. The Changing Faces of Rural America. In: Kandel W, Brown D, editors. Population Change and Rural Society. The Netherlands: Springer; 2006. pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sera LC, McPherson ML. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic changes associated with aging and implications for drug therapy. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2012;28:273–286. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowie MW, Slattum PW. Pharmacodynamics in older adults: a review. The American journal of geriatric pharmacotherapy. 2007;5:263–303. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Budnitz DS, Shehab N, Kegler SR, Richards CL. Medication use leading to emergency department visits for adverse drug events in older adults. Annals of internal medicine. 2007;147:755–765. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Southard EP, Neufeld JD, Laws S. Telemental health evaluations enhance access and efficiency in a critical access hospital emergency department. Telemedicine journal and e-health. 2014;20:664–668. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howieson DB, Camicioli R, Quinn J, et al. Natural history of cognitive decline in the old old. Neurology. 2003;60:1489–1494. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000063317.44167.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.GG F. Multidimensional Functional Assessment of Older Adults: The Duke Older Americans Resources and Services Procedures. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. STUDIES OF ILLNESS IN THE AGED. THE INDEX OF ADL: A STANDARDIZED MEASURE OF BIOLOGICAL AND PSYCHOSOCIAL FUNCTION. Jama. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folstein MF, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The Mini-Mental State Examination. Archives of general psychiatry. 1983;40:812. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790060110016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. The British journal of psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erten-Lyons D, Dodge HH, Woltjer R, et al. Neuropathologic basis of age-associated brain atrophy. JAMA neurology. 2013;70:616–622. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. Journal of psychiatric research. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodge HH, Zitzelberger T, Oken BS, Howieson D, Kaye J. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of Ginkgo biloba for the prevention of cognitive decline. Neurology. 2008;70:1809–1817. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000303814.13509.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Rural Health, Defining the Rural Population. Undated. Available at: http://www.hrsa.gov/ruralhealth/policy/definition_of_rural.html. Accessed.

- 30.United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Atlas of Rural and Small-town America. Last updated: Friday, April 11, 2014. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/atlas-of-rural-and-small-town-america/about-the-atlas.aspx. Accessed.

- 31.Leahy MJ, Thurber D, Calvert JF., Jr Benefits and challenges of research with the oldest old for participants and nurses. Geriatric nursing (New York, NY) 2005;26:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salvi F, Miller MD, Grilli A, et al. A manual of guidelines to score the modified cumulative illness rating scale and its validation in acute hospitalized elderly patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:1926–1931. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrison C, Britt H, Miller G, Henderson J. Examining different measures of multimorbidity, using a large prospective cross-sectional study in Australian general practice. BMJ open. 2014;4:e004694. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Structure and principles of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system. WHO Collaborating Center for Drug Statistics Methodology; [online] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campanelli CM. American Geriatrics Society Updated Beer’s Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults: The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beer’s Criteria Update Expert Panel. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60:616–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durazo EM, Jones MR, Wallace SP, Van Arsdal J, Aydin M, Stewart C. The health status and unique health challenges of rural older adults in California Policy brief. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2011. pp. 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing research reviews. 2011;10:430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Funkhouser E, Houston TK, Levine DA, Richman J, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI. Physician and patient influences on provider performance: beta-blockers in postmyocardial infarction management in the MI-Plus study. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2011;4:99–106. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.942318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beer’s criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Archives of internal medicine. 2003;163:2716–2724. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]