Abstract

Breslow thickness (BT) is a major prognostic factor of cutaneous melanoma (CM), the most fatal skin cancer. The genetic component of BT has only been explored by candidate gene studies with inconsistent results. Our objective was to uncover the genetic factors underlying BT using an hypothesis-free genome-wide approach. Our analysis strategy integrated a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for BT followed by pathway analysis of GWAS outcomes using the gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) method and epistasis analysis within BT-associated pathways. This strategy was applied to two large CM datasets with Hapmap3-imputed SNP data: the French MELARISK study for discovery (966 cases) and the MD Anderson Cancer Center study (1,546 cases) for replication. While no marginal effect of individual SNPs was revealed through GWAS, three pathways, defined by gene ontology (GO) categories were significantly enriched in genes associated with BT (false discovery rate ≤5% in both studies): hormone activity, cytokine activity and myeloid cell differentiation. Epistasis analysis, within each significant GO, identified a statistically significant interaction between CDC42 and SCIN SNPs (pmeta-int =2.2x10−6, which met the overall multiple-testing corrected threshold of 2.5x10−6). These two SNPs (and proxies) are strongly associated with CDC42 and SCIN gene expression levels and map to regulatory elements in skin cells. This interaction has important biological relevance since CDC42 and SCIN proteins have opposite effects in actin cytoskeleton organization and dynamics, a key mechanism underlying melanoma cell migration and invasion.

Keywords: Genome-wide association studies, pathway analysis, gene-gene interaction, melanoma, Breslow thickness

Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma (CM) is the most aggressive form of skin cancer and has shown a dramatic rise in incidence in fair skinned populations over the last decades.1 Mortality rates have also been rising between 1955 and 1985 but have stabilized in recent years. However, mortality from melanoma continues to increase among men aged 65 and older.2 Breslow thickness (BT), which is a measure of primary melanoma depth, represents the most important prognostic factor of this cancer.3 The 10-year survival rate was found to be 92% in patients with thin melanomas (BT < 1 mm) and to decrease to 50% in patients with melanomas more than 4 mm thick.3 BT has been reported to be associated with host factors that are also associated with melanoma risk. A greater BT was found to be consistently associated with older age at diagnosis and male sex and to be inversely associated with number of nevi.4, 5 To date, genetic studies of Breslow thickness have been limited to candidate genes, including genes associated with melanoma risk, and, for the most part, have led to marginal and/or inconsistent associations.5–7 Thus, the genetic factors influencing Breslow thickness are mostly unknown and deserve to be discovered using hypothesis-free genome-wide approaches.

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have been very successful in identifying thousands of loci associated with many diseases or traits,8 including 20 loci for risk of melanoma.9 These GWASs typically focus on the analysis of individual SNPs and, because of the large number of SNPs analyzed, require stringent thresholds to declare an association as genome-wide significant. Consequently, GWASs are underpowered to detect genetic variants which have small marginal effect but rather act jointly or interact with each other in disease or trait variability. Complementary approaches to GWAS, such as GWAS pathway analysis and epistasis analysis, have been proposed to overcome these issues. Pathway analysis of GWAS outcomes is based on the premise that genes do not work in isolation; instead, genes that belong to biological and functional units (pathways or gene sets) can harbor markers which might be detectable when examined jointly. This approach identifies pathways enriched in genes associated with the trait and can also provide novel insight into the trait biology. Another way to increase power of detecting association of markers with a trait is to conduct statistical analysis that considers gene-gene interactions; this is especially true for low marginal-effect SNPs. Pairwise SNP-SNP interactions can be investigated either at the genome-wide level or by using statistical and/or biological filtering procedures (such as pathway analysis) to limit the search for interactions among a subset of genetic markers10 and, thus, to increase statistical power by reducing the multiple testing burden. Therefore, the use of both GWAS and post-GWAS approaches can maximize power to uncover genes underlying complex phenotypes. Indeed, the integration of pathway and epistasis analyses has recently been successful in identifying two novel genes interacting in melanoma risk11 that were not detected by a large-scale meta-analysis of melanoma GWASs.9

The objective of this study is to identify genetic factors influencing Breslow thickness by applying a combination of GWAS and post-GWAS approaches to two large studies of melanoma with genome-wide SNP data: the French MELARISK study (966 cases), that served as the discovery dataset, and the North-American MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) study (1,546 cases), that was used as the replication dataset. For that purpose, we first conducted a genome-wide single-SNP association analysis to identify marginal effects of individual genetic variants associated with BT. This was followed by a pathway analysis of GWAS outcomes to identify gene sets enriched in genes associated with BT and the most promising candidates among genes driving the pathways through literature mining. Finally, we carried out an epistasis analysis within BT-associated pathways to identify interactions between genetic variants influencing BT. To the best of our knowledge, this is, to date, the most comprehensive assessment of the genetic factors influencing Breslow thickness.

Materials and methods

Study populations

Protocols of both MELARISK and MDACC studies have been approved by the ethical committees of Paris-Saint-Louis, Paris-Necker and Ile-de-France II (Paris, France) for the MELARISK study and by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (Houston, Texas) for the MDACC study. All subjects participating to these studies gave their written informed consent.

The MELARISK study comprised of 1,244 European-ancestry melanoma cases who were recruited through a nationwide network of French Dermatology Departments and Oncogenetic clinics between 1992 and 2011. The protocol of case recruitment and data collection has been described in detail elsewhere.12 Briefly, confirmation of each reported CM case was sought through review of medical records, review of pathological material, and/or from pathological reports. Information on Breslow thickness of the primary tumor was retrieved from medical and/or pathological records and was obtained together with age at diagnosis of melanoma and sex in 1,011 confirmed CM patients. The MDACC study has been previously described13 and consisted of 1,804 non-Hispanic patients with newly diagnosed CM who were recruited from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center between March 1998 and August 2008. Information on Breslow thickness was retrieved from patient records and maintained in the MD Anderson Melanoma Informatics, Tissue Resource, and Pathology Core and was obtained together with age at diagnosis of melanoma and sex in 1,804 CM patients. In both studies, for patients that had multiple primary melanomas, the Breslow thickness of the first melanoma was used.

Genotyping and quality control

MELARISK subjects were genotyped in three stages, as part of previous GWASs of melanoma risk.9, 14, 15 Genotyping was based on Illumina HumanHap300 Beadchip version 2 duo array for stage 1 (481 CM cases with known BT) and on Illumina Human610-Quad array for stages 2 and 3 (530 CM cases with known BT). MDACC samples were genotyped with the Illumina HumanOmni1-Quad_v1-0_B array.13 Standard QC measures were applied to samples and SNPs, as described previously for MELARISK9, 14, 15 and MDACC.13 After quality control (QC) of genotypic data, the number of melanoma patients kept for analysis was 966 in MELARISK and 1,546 in MDACC. To get the same set of SNPs across samples, genotypic imputations were carried out in each dataset (and by genotyping stage in MELARISK) using MaCH16 and Hapmap3 CEU population as reference panel. Only SNPs that had imputation quality score (rsq) ≥ 0.8 and minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 0.05 were retained for analysis. There were 1,032,745 SNPs that passed QC in MELARISK and 1,067,258 SNPs in MDACC.

Statistical analysis

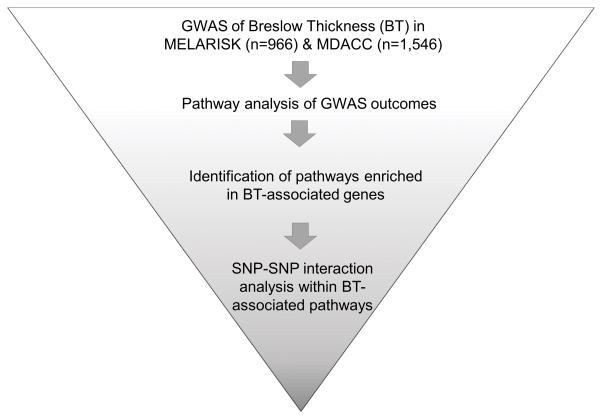

Descriptive statistics of sex, age at diagnosis and Breslow thickness and the effects of age and sex on BT were assessed in each dataset using Stata V12 (distributed by Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). Since BT is right-skewed, we used the logarithm to base 10 of BT (log10BT) for the latter and subsequent analyses. The workflow of our genome-wide analysis strategy is presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Workflow of analysis strategy.

Our analysis strategy included: - a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of individual SNPs with Breslow thickness (BT) (first-stage in MELARISK and second-stage in MDACC); - a pathway analysis of MELARISK and MDACC GWAS outcomes to identify pathways (defined by gene ontology categories) enriched in genes associated with BT; a SNP-SNP interaction analysis within BT-associated pathways to identify the interactive effect of genetic variants influencing BT.

Genome-wide single SNP association analysis

To assess the effect of single SNPs on BT, we performed a two-stage GWAS. In the first stage conducted in MELARISK, residual BT (after adjustment of log10BT on significant sex and age effects) was regressed onto SNP allele dosage (assuming an additive model) while adjusting for stage of genotyping, using Stata V12. Test of SNP effect was based on the Wald-test. All SNPs reaching a critical threshold of 10−5 were followed-up in MDACC at stage 2. The association analysis in MDACC was performed using ProbABEL17 assuming an additive model for SNP effect and adjusting for sex and age at diagnosis. The results of MELARISK and MDACC were combined using a fixed effects meta-analysis and a threshold (pmeta) of 5x10−8 was used to declare genome-wide significance.

Genome-wide pathway analysis

Pathway analysis was applied to the outcomes of MELARISK and MDACC GWASs. For that purpose, we used genome-wide single SNP statistics obtained from an MDACC GWAS of BT.18 Pathway analysis was based on the gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) approach implemented in the GenGen package.19 GSEA computes an enrichment score to detect gene-sets significantly enriched in genes associated with the trait compared to the whole genome. Imputed SNPs from BT GWAS were first mapped to genes (between the start site and 3’-untranslated region of each gene) using dbSNP Build 132 and human Genome Build 37.1. The GWAS-single SNP association statistic for the most significant SNP in each gene was used to represent the gene. To map genes to pathways, we used Gene Ontology (GO) categories as provided by GenGen (i.e. biological process and molecular function level-4 GO categories to minimize the number of overlapping GOs). Our analysis was also restricted to GOs that contained at least 20 and at most 200 genes to avoid testing overly narrow or broad functional categories. The enrichment score of a pathway was based on the weighted Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like running sum statistic.19 Statistical significance of pathway enrichment scores was determined by 100,000 permutations of SNP statistics. These permutations allow not only computing empirical p-values and false discovery rates (FDRs) to correct for multiple testing but also normalizing the observed enrichment scores based on the null distribution of these scores, hence adjusting for variation in gene length and pathway size. We used a FDR 5% as a stringent criterion for statistical significance in the discovery dataset and a FDR 5% in the replication dataset as a criterion for a validated result. We identified the genes driving the enrichment score of each significant pathway (also called “leading edge genes”). To further prioritize the leading edge genes shared by MELARISK and MDACC as relevant candidates for BT, we used text mining based on the domain knowledge score tool (DKS).20 DKS performs automated PubMED searches with each gene and any combination of modifier terms. The modifier terms were “melanoma” and either “Breslow thickness” or any one of cancer survival or progression-related terms ("metastasis", "progression", "recurrence", "survival", "prognosis", "invasion", "invasiveness", "mortality"). The DKS that each gene gets is the number of PubMed abstracts and/or titles retrieved with the querying terms. We selected as BT candidates the leading edge genes belonging to the top 10% of DKS distribution.

SNP-SNP interaction analysis within BT-associated pathways

In MELARISK, we analyzed all cross-gene SNP-SNP interactions for leading edge genes shared by MELARISK and MDACC within each BT-associated pathway. Pairwise SNP-SNP interactions were evaluated by regression analysis of residual BT assuming an additive model and adjusting for genotyping stage using Stata V12. The additive effect of a SNP was represented by a variable that was coded 1, 0, and -1 for homozygote for the minor (effect) allele, heterozygote, and homozygote for the major (reference) allele, respectively. The interaction term was the multiplication of these variables between SNPs. Since we had imputed SNPs, each SNP was coded as the weighted average of these three genotypic values with weight being the probability of each genotype. Test of interaction was performed by comparing the full model, which included the additive effects of the two SNPs plus the interaction term to the restricted model without interaction, using a likelihood-ratio test which follows a χ2 distribution with one degree of freedom.

For each gene, we examined all SNPs lying from 50kb upstream to 50kb downstream of the gene (Build 37.1). We discarded strongly correlated SNPs (r2 ≥ 0.8) and all SNP pairs for which one or more of the 9 genotype-by-genotype combinations appeared in fewer than five subjects. All pairs of SNPs showing suggestive evidence for interaction (pint ≤ 10−4) in MELARISK were subjected to replication in MDACC. SNP pairs that replicated in MDACC at the nominal 5% level were further meta-analyzed from the two datasets using a fixed-effects model; the meta-analyzed interaction effect was tested using a Wald test (pmeta-int). To correct for multiple testing, we used the same hierarchical method as previously described.11 We first computed, for each gene pair, the effective number of independent SNP-SNP interaction tests using an extension of Li and Ji’s method.21 The effective number of independent tests in a pathway was estimated by the sum of the effective numbers of independent tests for a gene pair over all gene pairs tested within that pathway in the discovery dataset. The corrected critical threshold for the number of tests in a pathway (Tpathway) was thus equal to the 5% type I error divided by the effective number of independent tests in that pathway. Finally, to correct for the number of BT-associated pathways tested, we applied a Bonferroni correction to the pathway-corrected threshold (Tpathway) to get the overall critical threshold (Toverall).

Results

The characteristics of 966 MELARISK and 1,546 MDACC melanoma patients are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The sex distribution differed between the two datasets (p<10−4) with a lower proportion of males (45%) in MELARISK as compared to MDACC (58%). The age at diagnosis of melanoma was younger in MELARISK (46.5 ± 17.7) than in MDACC (52.2 ± 14.5; p<10−4). The mean Breslow thickness of primary melanomas was also lower in MELARISK than in MDACC (1.46 ± 2.04 mm vs 1.94 ± 1.56 mm; p <10−4). Assessment of the effect of sex and age at melanoma diagnosis on log10BT showed significant effects of sex, age and age squared in MELARISK and sex and age in MDACC. There was no interaction between sex and age in either dataset. After adjustment on these covariates, the residual BT values had similar distribution in the two datasets (p=0.74).

Genome-wide single SNP association analysis

In the first stage GWAS conducted in MELARISK, no evidence of any systematic bias was observed (see quantile-quantile (QQ) plot in Supplementary Figure S1; the genomic inflation factor (λ) was equal to 1.01). A total of five loci (1p34.1, 5q34, 12q23.3, 13q12.3, 18q11.2) showed associations with BT exceeding the stage-1 screening threshold of p ≤ 10−5 (p-values ranging between 4x10−7 and 8x10−6 for the lead SNPs; Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figure S2). However, none of these SNPs was even nominally significant in MDACC and their meta-analyzed effect did not reach genome-wide significance (Supplementary Table S2).

Genome-wide pathway analysis

Pathway analysis was applied to MELARISK and MDACC GWAS outcomes to detect gene sets enriched in genes associated with BT. As for MELARISK, the MDACC GWAS outcomes did not show any particular bias (λ=1.0) and did not reveal any signal reaching genome-wide significance.18 In MELARISK, 459,637 out of 1,032,745 Hapmap3-imputed SNPs were mapped to 21,810 genes. Of these, 6,873 genes were assigned to 316 level-4 GO categories. In MDACC, 475,093 out of 1,067,258 SNPs were mapped to 22,096 genes. Of these, 6,909 genes were assigned to 319 level-4 GO categories. A total of 28 GOs reached the threshold for statistical significance (FDR ≤ 0.05) in MELARISK. Three of these GOs were successfully replicated in MDACC (FDR ≤0.05) and were the following: hormone activity (GO:0005179), cytokine activity (GO:0005125) and myeloid cell differentiation (GO:0030099) (Table 1). A total of 63 leading edge genes were driving the pathway enrichment scores in both MELARISK and MDACC (Table 1) and were distributed almost uniquely among the three significant GOs. Text mining of PubMed abstracts applied to these leading edge genes pinpointed five candidates having a Domain Knowledge Score (DKS) in the top 10% of the pathway-specific DKS distribution (Supplementary Figure S3). These genes were POMC for hormone activity, VEGFA, IL1B, TNFSF10 for cytokine activity and CDC42 for myeloid cell differentiation.

Table 1.

Pathways associated with Breslow thickness in MELARISK and MDACC datasets

| Pathway (GO class) | MELARISK

|

MDACC

|

No. of leading edge genes shared by the two datasets3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of genes1 | p2 | FDR2 | No. of genes1 | p2 | FDR2 | ||

| Hormone activity (GO:0005179) | 85 | 4.0x10−5 | 2.0x10−3 | 87 | 4.6x10−4 | 0.01 | 16 |

| Cytokine activity (GO:0005125) | 183 | 1.3x10−3 | 0.03 | 188 | 7.0x10−5 | 6.0x10−3 | 31 |

| Myeloid cell differentiation (GO:0030099) | 81 | 1.8x10−3 | 0.04 | 83 | 9.5x10−4 | 0.02 | 16 |

Number of genes in a pathway having at least one GWAS SNP mapped to a gene

Empirical p-value and False Discovery Rate (FDR) of a pathway estimated by 100,000 permutations of SNP statistics

The leading edge genes are the genes which drive the enrichment score of the pathway

SNP-SNP interaction analysis within BT-associated pathways

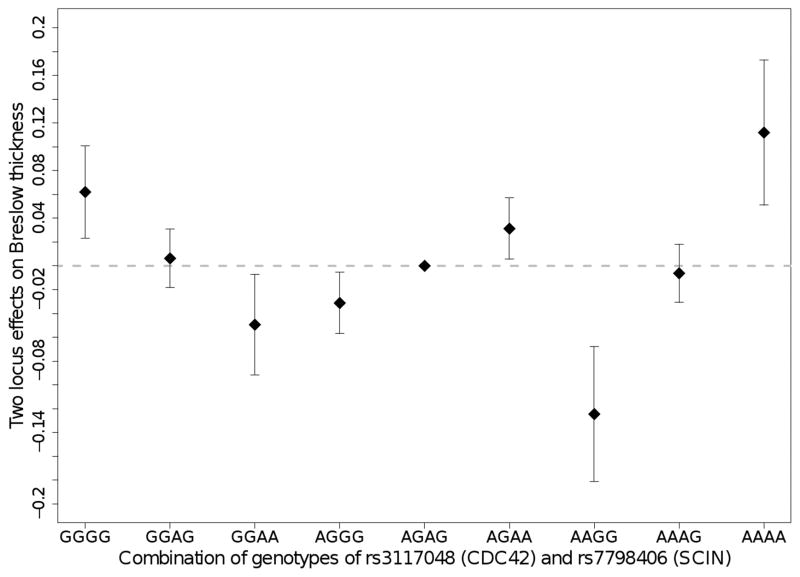

In the MELARISK discovery dataset, we examined 120, 465 and 120 gene pairs (corresponding to 20,213, 167,041 and 28,495 SNP pairs tested) in the hormone activity, cytokine activity and myeloid cell differentiation GOs, respectively. There were three SNP pairs harbored by three gene pairs that had pint ≤ 10−4 in MELARISK and replicated at the nominal 5% level in MDACC (Table 2). Two of these SNP pairs, related to BMP6/NRG1 and CYFIP2/PRL gene pairs and belonging to the cytokine activity GO, had an inverse direction of interaction effect in MDACC as compared to MELARISK and were therefore not significant in the meta-analysis of the two datasets (pmeta-int>0.20). However, one SNP pair related to CDC42 and SCIN loci in the myeloid cell differentiation GO, had the same direction of interaction effect in the two datasets and showed increased evidence for interaction in the meta-analysis of MELARISK and MDACC (pint=5.6x10−5 in MELARISK, pint=7.1x10−3 in MDACC, and pmeta-int=2.2x10−6 in meta-analysis, which is less than both multiple testing corrected thresholds, Tpathway = 7.5x10−6 and Toverall = 2.5x10−6, Supplementary Table S3). This statistically significant SNP pair showed a pattern of interaction in which the effect associated with genotype GG (or AA) of rs7798406 (SCIN) had an inverse effect on BT depending on the genotype, GG (or AA), at rs3117048 (CDC42) (Figure 2). We also noted that for this SNP pair, no single SNP had a nominally significant marginal effect and, in presence of interaction in the model, the SNP main effects were also not nominally significant in either MELARISK or MDACC except for rs7798406 (SCIN) in MELARISK (p=0.02) (Supplementary Table S4). Further analysis of SNPs, that were in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD; r2 ≥ 0.80) with rs3117048 and/or rs7798406 and were thus discarded from our initial analysis (see methods), showed additional interaction effects involving two other SNPs CDC42 rs2501299 (r2=0.89 with rs3117048) and SCIN rs991317 (r2=0.88 with rs7798406). These interactions reached (or almost reached) the multiple-testing corrected thresholds, which strengthens our finding (Supplementary Table S3 and S5).

Table 2.

SNP pairs showing evidence for interaction effect on Breslow Thickness

| Pathway | SNP | Chromosome | Gene1 | Alleles E/R2 | EAF2 | MELARISK

|

MDACC

|

Meta-analysis

|

Multiple-testing corrected thresholds6

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction effect | Interaction effect | Interaction effect | |||||||||||

| βint3 (seint) | pint4 | βint3 (seint) | pint4 | βmeta-int5 (semeta-int) | pmeta-int5 | Tpathway | Toverall | ||||||

| Myeloid cell differentiation | |||||||||||||

| rs3117048 | 1p36.1 | 34kU CDC42 | A/G | 0.31 | 0.11 | 5.6x10−5 | 0.07 | 7.1x10−3 | 0.09 | 2.2x10−6 | 7.5x10−6 | 2.5x10−6 | |

| rs7798406 | 7p21.3 | SCIN (intron) | A/G | 0.46 | (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | ||||||

| Cytokine activity | |||||||||||||

| rs9505270 | 6p24-p23 | BMP6 (intron) | A/G | 0.27 | 0.12 | 2.1x10−5 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 1.5x10−6 | 5.0x10−7 | |

| rs4276645 | 8p12 | NRG1 (intron) | A/G | 0.33 | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | ||||||

| rs3734034 | 5q33.3 | CYFIP2 (exon) | T/C | 0.35 | 0.10 | 3.7x10−5 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.28 | |||

| rs2066266 | 6p22.3 | 17kD PRL | G/A | 0.44 | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | ||||||

Gene symbol; k indicates distance to gene in kilobases (Build 37.1); U indicates "upstream of"; D indicates "downstream of ". Upstream and downstream respectively refer to the 5’ and 3’ ends of the coding strand of each gene.

E/R=Effect allele/Reference allele; EAF=Effect allele frequency.

βint is the regression coefficient of interaction effect between SNPs on Breslow thickness; seint is the standard error of βint

pint is the p-value of the likelihood-ratio test for interaction (one degree of freedom test)

βmeta-int and semeta-int are the regression coefficient and standard error of interaction effect between SNPs in the meta-analysis of MELARISK and MDACC; pmeta-int is the p-value associated with the Wald test of meta-analysed interaction effect

Tpathway and Toverall are respectively the pathway-corrected and overall-corrected critical thresholds to take into account multiple testing.

Fig. 2. Two-locus effects and 95% confidence intervals on Breslow thickness for each genotypic combination of rs3117048 (CDC42) and rs7798406 (SCIN) SNPs.

The x and y axes represent genotypic combinations of rs3117048 and rs7798406 SNPs and the effect of these genotypes on BT, respectively. The genotype-specific effects were computed using the estimates of SNP main effects and interaction obtained from the combined analysis of MELARISK and MDACC. The effect of a SNP was coded 1, 0, and -1 for homozygote for the minor (effect) allele, heterozygote, and homozygote for the major (reference) allele, respectively and the interaction was represented by the multiplication of these variables between SNPs.

Functional annotation of CDC42 and SCIN SNPs

None of the SNPs that have a significant interaction effect on BT were located within a coding sequence. Using data on expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTLs) generated in blood, lymphoblastoïd cell lines, skin and adipose tissue22–24 and data on regulatory elements from the ENCODE and NIH ROADMAP Epigenomics projects,25, 26 we investigated whether the interacting SNPs influence CDC42 and SCIN gene expression levels (cis-eQTLs) and/or map to functionally important regulatory regions (Table 3). In fact, rs3117048, located 34kb upstream of CDC42, is a strong cis-eQTL for CDC42 in blood (p=1.5x10−55) and maps to enhancer histone marks in keratinocytes and binding sites for transcription factors (Table 3). The SNP rs7798406, located in the fourth intron of SCIN, is a cis-eQTL in sub-cutaneous adipose tissue (p=1.9x10−5) and maps to binding sites of transcription factors. Moreover, by interrogating not only the Hapmap3-imputed SNP data of the current study but also the 1,000 Genomes project database, we found proxies of rs3117048 and rs7798406 that are also cis-eQTLs for CDC42 and SCIN respectively and map within histone activating regions, DNAse I hypersensitivity sites and/or transcription factor binding sites (Table 3). Notably, rs2501299 (33kb upstream of CDC42, r2=0.89 with rs3117048) is a strong cis-eQTL for CDC42 in blood (p=8.2x10−65) and maps to enhancer histone marks in keratinocytes and melanocytes and rs6956491 (within SCIN intron 5; r2 = 0.90 with rs7798406) maps to a DNAse I hypersensitivity site in skin fibroblasts.

Table 3.

Functional annotations of CDC42 and SCIN SNPs

| Gene | SNP | Chromosome: Position | Variant Location1 | r2 with rs3117048 or rs7798406 | Cis-eQTL data

|

Regulatory elements

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p2 | Tissue | Promoter histones marks | Enhancer histones marks | DNase I hyper sensitivity site | Transcription factor binding site | |||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| CDC42 | ||||||||||

| rs7537414 | 1:22,325,016 | 54kU | 0.97 | 8.8x10−8 | LCL | Yes | Yes (melanocytes) | Yes | TCF3, LMO2, RAD21, ZEB1 | |

| rs3117048 | 1:22,345,093 | 34kU | - | 1.5x10−55 | Blood | No | Yes (keratinocytes) | No | HIF1A, MAF | |

| rs2501299 | 1:22,345,647 | 33kU | 0.89 | 8.2x10−65 | Blood | Yes (keratinocytes) | Yes (keratinocytes,melanocytes) | Yes (keratinocytes,melanocytes) | ELF1, EGR1, EHF, NR3C1,SPI1,RAD21 | |

| SCIN | ||||||||||

| rs7798406 | 7:12,644,033 | Intron 4 | - | 1.9x10−5 | Adipose tissue | No | No | No | CDX2, HOXA10, HOXC9 | |

| rs6956491 | 7:12,650,851 | Intron 5 | 0.90 | 4.5x10−6 | Adipose tissue | Yes | Yes | Yes (skin fibroblasts) | SP1, BPTF,ARID5B | |

| rs11763533 | 7:12,657,746 | Intron 5 | 0.90 | 4.6x10−6 | Adipose tissue | No | Yes | Yes | CTCF | |

The SNPs rs3117048 (CDC42) and rs7798406 (SCIN), which were identified as having a statistically significant interaction effect on Breslow thickness were queried for correlated proxies (r2 ≥ 0.8) using the Hapmap3-imputed SNP data of the current study and the 1,000 Genomes project database. All correlated SNPs were tested for their association with CDC42 or SCIN gene expression levels using eQTL data generated in blood,24 lymphoblastoïd cell lines (LCL),22,23 sub-cutaneous adipose tissue, and skin.22 These SNPs were also mapped to regulatory elements using ENCODE and ROADMAP data and the HaploReg tool (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mammals/haploreg/haploreg.php).

k indicates distance to gene in kilobases (Build 37.1); U indicates "upstream of".

p-value of association between SNP and gene expression levels provided by eQTL databases.

Discussion

For the first time, we investigated genetic factors associated with Breslow thickness using an hypothesis-free strategy that combines genome-wide single-SNP analysis, pathway analysis and epistasis analysis within BT-associated pathways. While no marginal effect of individual SNPs on BT was revealed through GWAS, pathway analysis, which allows testing for association on the basis of functional units such as gene ontology categories, identified three gene sets that were significantly enriched in genes influencing BT. Epistasis analysis within these BT-associated pathways showed significant evidence for interaction between potentially functional genetic variants at CDC42 and SCIN loci.

While the GWAS identified SNPs modestly associated with BT in the discovery MELARISK dataset, none of these SNPs showed any consistent association in MDACC and therefore any improvement of association signals when the results of the two studies were combined. We checked that our two-stage study had enough power (≥70%) to detect individual SNPs accounting for at least 2.5% of BT variance. This was approximately the proportion of BT variance individually accounted for by SNPs detected in MELARISK but which were not replicated in MDACC. Although these two datasets showed differences according to sex and age at diagnosis of melanoma, the difference in the distribution of BT was no longer significant after adjusting for these covariates. This indicates that the genetic variants underlying BT are likely to have a small marginal effect and/or to be involved in complex mechanisms, which makes their detection difficult by single SNP analysis.

The three GO categories, hormone activity, cytokine activity and myeloid cell differentiation, that were consistently identified by pathway-based analysis in the two melanoma datasets, were driven by genes modestly associated with BT (all had best SNP p-values greater than 10−4). To further assess whether these three pathways were specific to BT, we repeated pathway analysis for ulceration, another melanoma prognostic factor, that was available in the majority of MELARISK and MDACC melanoma cases. While enrichment of hormone activity in ulceration association signals had FDR that reached 5% in MELARISK but only 10% in MDACC, the other two pathways, cytokine activity and myeloid cell differentiation, did not show significant enrichment (results not shown). This indicates that the genetic factors underlying BT and ulceration are likely to be distinct for the most part. The identification of the hormone activity pathway fits well the observed sex disparities in melanoma outcomes.27 Indeed, among the biological mechanisms that have been proposed to explain the prognostic advantage of female compared with male patients with melanoma, stand the differences in sex hormones levels and estrogen and androgen receptor expression.27 Our finding of an enrichment of hormone activity GO in genes associated with BT strengthens the potential role of sex hormones in melanoma outcomes. The association of the cytokine activity pathway with BT has biological relevance given the key role of immune-related mechanisms in melanoma progression.28 A number of cytokines have been found to be highly expressed in human melanomas, both in primary tumors and metastases.29 Interestingly, the cytokine activity GO was previously found associated with melanoma risk using the same two datasets.11 This supports the importance of this pathway in both melanoma occurrence and progression as recently evidenced by the identification of immune signatures associated with survival in large-scale genomic data of cutaneous melanomas30 and the growing development of immunotherapy regimens.31 The third identified GO, myeloid cell differentiation, is also relevant to melanoma outcomes since myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are one of the drivers of tumor-mediated immune evasion.32 Interestingly, the pro-tumoral properties of intra-tumoral myeloid cells have been evidenced by a mouse model of spontaneous melanoma33 and the level of circulating MDSCs was found to have a prognostic value in advanced melanoma.34

A text-mining approach applied to genes driving the significant pathways enabled to pinpoint five BT candidate genes. Two of these genes, VEGFA and POMC, have been previously reported to be related to BT. Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) polymorphisms were found associated with BT35 and VEGFA expression was associated with BT in melanoma tumors.36 The POMC (pro-opiomelanocortin) gene encodes the precursor of α-MSH (melanocyte-stimulating hormone) that binds to the melanocortin receptor 1 encoded by MC1R, a gene found consistently associated with melanoma risk37 and potentially with BT.7

Epistasis analysis within the three BT-associated pathways identified a statistically significant interaction between two CDC42 and SCIN SNPs that satisfied the multiple-testing correction. Interactions were further found with proxies of these SNPs, which strengthens our finding. This is remarkable since very few of the increasing number of studies focusing on gene-gene interactions have been successful in detecting statistically significant interactions and/or showing replication. Although our analysis was based on imputed SNPs, we maximized imputation accuracy by using stringent QC criteria to retain SNPs for analysis. For those interacting SNPs that were genotyped, the correlation between genotyped and imputed SNPs was at least 0.95. We assumed an additive genetic model but further analysis, under a more general model that included additive and dominance terms for main effects and interaction, did not show any departure from additivity (results not shown). Exploration of functional annotations of the interacting SNPs showed that these SNPs and proxies are potentially functional since they are strongly associated with CDC42 and SCIN gene expression levels and map within regulatory elements in melanocytes, keratinocytes and/or skin fibroblasts. The proteins encoded by CDC42 (cell division cycle 42) and SCIN (scinderin) have particularly relevant biological functions regarding cancer invasion. The cell division cycle 42 (CDC42) protein belongs to the family of Rho GTPases that play pivotal roles in the control of cell proliferation, cytoskeletal reorganization and cell migration.38 It is overexpressed in a number of cancers and influences oncogenic transformation and invasion.39 CDC42 was found to be involved in melanoma invasiveness40 and to have a melanocytic expression positively correlated with Breslow thickness in patients with fatal outcome.41 Moreover, proteomic analysis of melanocytes from dysplastic nevus and normal skin demonstrated that CDC42 has increased expression in dysplastic nevi.42 The scinderin protein (also known as adseverin), encoded by SCIN, is a calcium-dependent actin severing and capping protein, which belongs to the gelsolin superfamily. Proteins of this superfamily are regulators of actin cytoskeleton dynamics and are involved in many actin-related processes.43 SCIN is highly expressed in cancers and its expression was related to cell proliferation.44 Notably, CDC42 and scinderin have opposite effects in actin dynamics which drives cell shape changes and motility and therefore plays a key role in cancer cell migration and invasion including melanoma cells.45, 46 CDC42 stimulates actin filament assembly while scinderin severs the actin filaments. Both CDC42 and scinderin activities are related to PIP2 (phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate): CDC42 mediates PIP2-induced actin polymerization47 while PIP2 inhibits the actin-severing activity of scinderin.43 Another player of interest in actin and cytoskeleton related processes and which promotes cell proliferation and invasion is AFAP1L2 (actin filament associated protein 1-like 2 also known as XB130)48 encoded by AFAP1L2 gene that was recently found to interact with TERF1, one of the telomere maintenance genes, in melanoma risk.11 All these observations provide strong support for our finding and outline the importance of actin dynamics-related genes in melanoma occurrence and progression. Further experimental studies are of course needed to provide better insight into the mechanisms involved.

In conclusion, this study shows that examination of the joint effects of multiple genetic variants and their interactions represents a powerful approach to disentangle the mechanisms underlying complex phenotypes. Indeed, it allowed not only identifying pathways enriched in genes associated with BT but also pointing out strong candidates underlying BT. Of particular interest is the significant interaction found between CDC42 and SCIN, which has important biological relevance given the key role of the proteins encoded by these genes in controlling cytoskeleton organization and actin dynamics and, consequently, in regulating melanoma invasion.

Supplementary Material

What’s new?

Breslow thickness (BT) is a major prognostic factor for melanoma. In this study, the authors present a comprehensive analysis strategy to identify the genetic factors influencing BT. By integrating genome-wide association, pathway and epistasis analyses, they identified three pathways associated with BT and showed significant interaction between variants at CDC42 and SCIN loci. This finding is biologically relevant, given the opposite effects of CDC42 and SCIN proteins in actin dynamics, a key mechanism underlying melanoma cell invasion.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the French Familial Study Group for their contribution to the MELARISK collection (P. Andry-Benzaquen, B. Bachollet, F. Bérard, P. Berthet, F. Boitier, V. Bonadona, B. Bressac-de Paillerets, JL. Bonafé, JM. Bonnetblanc, F. Cambazard, O. Caron, F. Caux, J. Chevrant-Breton, A. Chompret (deceased), S. Dalle, L. Demange, O. Dereure, MX. Doré, MS. Doutre, C. Dugast, L. Faivre, F. Grange, Ph. Humbert, P. Joly, D. Kerob, C. Lasset, MT. Leccia, G. Lenoir, D. Leroux, J. Levang, D. Lipsker, S. Mansard, L. Martin, T. Martin-Denavit, C. Mateus, JL. Michel, P. Morel, L. Olivier-Faivre, JL. Perrot, C. Robert, S. Ronger-Savle, B. Sassolas, P. Souteyrand, D. Stoppa-Lyonnet, L. Thomas, P. Vabres, E. Wierzbicka). They acknowledge that the biological specimens of the French MELARISK study were obtained from the Institut Gustave Roussy and Fondation Jean Dausset–CEPH Biobanks. They thank the Centre National de Génotypage (CNG-CEA, Evry, France) and Service XS (Leiden, the Netherlands) for performing genome-wide genotyping in the MELARISK study. They thank the John Hopkins University Center for Inherited Disease Research for conducting high-throughput genotyping and the University of Washington for the performance of quality control of the high-density SNP data of the MD Anderson Cancer Center cohort. M. Brossard was supported by doctoral fellowships from Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (LNCC) and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM).

Funding

Grant sponsor: Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (PHRC); Grant number: AOM-07-195; Grant sponsor: Institut National du Cancer (INCa); Grant number: INCa_5982; Grant sponsor: Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer; Grant number: PRE 09/FD and doctoral fellowship n° 2010.239; Grant sponsor: Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM); Grant number: FDT20130928343; Grant sponsor: the European Commission under the 6th Framework Programme; Grant number: LSH-CT-2006-018702; Grant sponsors: National Institutes of Health (NIH); Grant numbers: R01CA100264, 2P50CA093459, P30CA016672, R01CA133996, 5R03CA17379202; Grant sponsor: National Cancer Institute; Grant number: SPORE P50 CA093459; Grant sponsors: Philanthropic contributions to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Moon Shots Program, the Miriam and Jim Mulva Research Fund, the Peterson Fund for Melanoma Research, the Patrick M. McCarthy Foundation.

Abbreviations

- AFAP1L2

actin filament associated protein 1-like 2

- BMP6

bone morphogenetic protein 6

- BT

Breslow thickness

- CDC42

cell division cycle 42

- CEU

Northern Europeans from Utah

- CM

cutaneous melanoma

- CYFIP2

cytoplasmic FMR1 interacting protein 2

- DKS

Domain Knowledge Score

- IL1B

interleukin 1, beta

- MC1R

melanocortin 1 receptor (alpha melanocyte stimulating hormone receptor)

- MDSCs

myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- NRG1

neuregulin 1

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- POMC

pro-opiomelanocortin

- PRL

prolactin

- SCIN

scinderin

- TERF1

telomeric repeat binding factor (NIMA-interacting) 1

- TNFSF10

tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 10

- VEGFA

vascular endothelial growth factor A

- α-MSH

melanocyte-stimulating hormone

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Nikolaou V, Stratigos AJ. Emerging trends in the epidemiology of melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:11–9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linos E, Swetter SM, Cockburn MG, et al. Increasing burden of melanoma in the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1666–74. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199–206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osborne JE, Hutchinson PE. Clinical correlates of Breslow thickness of malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:476–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cadby G, Ward SV, Cole JM, et al. The association of host and genetic melanoma risk factors with Breslow thickness in the Western Australian Melanoma Health Study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:851–7. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward KA, Lazovich D, Hordinsky MK. Germline melanoma susceptibility and prognostic genes: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1055–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies JR, Randerson-Moor J, Kukalizch K, et al. Inherited variants in the MC1R gene and survival from cutaneous melanoma: a BioGenoMEL study. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012;25:384–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2012.00982.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hindorff LA, MacArthur J, Morales J, et al. [Accessed [18/06/2015]];A Catalog of Published Genome-Wide Association Studies. Available at: www.genome.gov/gwastudies.

- 9.Law MH, Bishop DT, Lee JE, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies five new susceptibility loci for cutaneous malignant melanoma. Nat Genet. 2015;47:987–95. doi: 10.1038/ng.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun X, Lu Q, Mukherjee S, et al. Analysis pipeline for the epistasis search - statistical versus biological filtering. Front Genet. 2014;5:106. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brossard M, Fang S, Vaysse A, et al. Integrated pathway and epistasis analysis reveals interactive effect of genetic variants at TERF1 and AFAP1L2 loci on melanoma risk. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1901–09. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaudru V, Chompret A, Bressac-de Paillerets B, et al. Influence of genes, nevi, and sun sensitivity on melanoma risk in a family sample unselected by family history and in melanoma-prone families. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:785–95. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amos CI, Wang LE, Lee JE, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel loci predisposing to cutaneous melanoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:5012–23. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishop DT, Demenais F, Iles MM, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies three loci associated with melanoma risk. Nat Genet. 2009;41:920–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrett JH, Iles MM, Harland M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies three new melanoma susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1108–13. doi: 10.1038/ng.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, et al. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:816–34. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aulchenko YS, Struchalin MV, van Duijn CM. ProbABEL package for genome-wide association analysis of imputed data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang S, Wang Y, Deng D, et al. GenoMEL group. Genetic determinants of Breslow tumor thickness and their impact on melanoma progression. 64th Annual Meeting of The American Society of Human Genetics; 2014; San Diego, California. http://www.ashg.org/2014meeting/pdf/2014_ASHG_Meeting_Poster%20Abstracts.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang K, Li M, Bucan M. Pathway-based approaches for analysis of genomewide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1278–83. doi: 10.1086/522374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium. Network-based multiple sclerosis pathway analysis with GWAS data from 15,000 cases and 30,000 controls. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92:854–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Ji L. Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity (Edinb) 2005;95:221–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grundberg E, Small KS, Hedman AK, et al. Mapping cis- and trans-regulatory effects across multiple tissues in twins. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1084–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang L, Morar N, Dixon AL, et al. A cross-platform analysis of 14,177 expression quantitative trait loci derived from lymphoblastoid cell lines. Genome Res. 2013;23:716–26. doi: 10.1101/gr.142521.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westra HJ, Peters MJ, Esko T, et al. Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1238–43. doi: 10.1038/ng.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein BE, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Costello JF, et al. The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1045–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The ENCODE project consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nosrati A, Wei ML. Sex disparities in melanoma outcomes: the role of biology. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2014;563:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rangwala S, Tsai KY. Roles of the immune system in skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:953–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elias EG, Hasskamp JH, Sharma BK. Cytokines and growth factors expressed by human cutaneous melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 2010;2:794–808. doi: 10.3390/cancers2020794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Cancer Genome Atlas network. Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma. Cell. 2015;161:1681–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rotte A, Bhandaru M, Zhou Y, et al. Immunotherapy of melanoma: Present options and future promises. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015;34:115–28. doi: 10.1007/s10555-014-9542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diaz-Montero CM, Finke J, Montero AJ. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer: therapeutic, predictive, and prognostic implications. Semin Oncol. 2014;41:174–84. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lengagne R, Pommier A, Caron J, et al. T cells contribute to tumor progression by favoring pro-tumoral properties of intra-tumoral myeloid cells in a mouse model for spontaneous melanoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang H, Gebhardt C, Umansky L, et al. Elevated chronic inflammatory factors and myeloid-derived suppressor cells indicate poor prognosis in advanced melanoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:2352–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howell WM, Bateman AC, Turner SJ, et al. Influence of vascular endothelial growth factor single nucleotide polymorphisms on tumour development in cutaneous malignant melanoma. Genes Immun. 2002;3:229–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajabi P, Neshat A, Mokhtari M, et al. The role of VEGF in melanoma progression. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:534–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beaumont KA, Liu YY, Sturm RA. The melanocortin-1 receptor gene polymorphism and association with human skin cancer. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2009;88:85–153. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1173(09)88004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hall A. Rho family GTPases. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:1378–82. doi: 10.1042/BST20120103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stengel K, Zheng Y. Cdc42 in oncogenic transformation, invasion, and tumorigenesis. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1415–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gadea G, Sanz-Moreno V, Self A, et al. DOCK10-mediated Cdc42 activation is necessary for amoeboid invasion of melanoma cells. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1456–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tucci MG, Lucarini G, Brancorsini D, et al. Involvement of E-cadherin, beta-catenin, Cdc42 and CXCR4 in the progression and prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1212–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao L, van Nieuwpoort FA, Out-Luiting JJ, et al. Genome-wide analysis of gene and protein expression of dysplastic naevus cells. J Skin Cancer. 2012;2012:981308. doi: 10.1155/2012/981308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nag S, Larsson M, Robinson RC, et al. Gelsolin: the tail of a molecular gymnast. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2013;70:360–84. doi: 10.1002/cm.21117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang D, Sun SQ, Yu YH, et al. Suppression of SCIN inhibits human prostate cancer cell proliferation and induces G0/G1 phase arrest. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:161–6. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fischer RS, Fowler VM. Thematic Minireview Series: The State of the Cytoskeleton in 2015. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:17133–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.663716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaggioli C, Sahai E. Melanoma invasion - current knowledge and future directions. Pigment Cell Res. 2007;20:161–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2007.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen F, Ma L, Parrini MC, et al. Cdc42 is required for PIP(2)-induced actin polymerization and early development but not for cell viability. Curr Biol. 2000;10:758–65. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lodyga M, Bai XH, Kapus A, et al. Adaptor protein XB130 is a Rac-controlled component of lamellipodia that regulates cell motility and invasion. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:4156–69. doi: 10.1242/jcs.071050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.