Abstract

Background: Postpartum depression (PPD) is a common complication of childbearing, but the course of PPD is not well understood. We analyze trajectories of depression and key risk factors associated with these trajectories in the peripartum and postpartum period.

Methods: Women in The First Baby Study, a cohort of 3006 women pregnant with their first baby, completed telephone surveys measuring depression during the mother's third trimester, and at 1, 6, and 12 months postpartum. Depression was assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. A semiparametric mixture model was used to estimate distinct group-based developmental trajectories of depression and determine whether trajectory group membership varied according to maternal characteristics.

Results: A total of 2802 (93%) of mothers completed interviews through 12 months. The mixture model indicated six distinct depression trajectories. A history of anxiety or depression, unattached marital status, and inadequate social support were significantly associated with higher odds of belonging to trajectory groups with greater depression. Most of the depression trajectories were stable or slightly decreased over time, but one depression trajectory, encompassing 1.7% of the mothers, showed women who were nondepressed at the third trimester, but became depressed at 6 months postpartum and were increasingly depressed at 12 months after birth.

Conclusions: This trajectory study indicates that women who are depressed during pregnancy tend to remain depressed during the first year postpartum or improve slightly, but an important minority of women become newly and increasingly depressed over the course of the first year after first childbirth.

Keywords: : depression, postpartum, women's health, reproductive health, social support, marital status, trajectory analysis

Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD), affecting ∼13%–14% of women, is the most common complication of childbearing.1,2 Symptoms include excessive worrying, tearfulness, loss of appetite, feelings of inadequacy, insomnia, and depressed mood.3 To be classified as PPD, symptoms of major depression emerge within the peripartum period through 4 weeks postpartum, must be present for at least 2 weeks, and must interfere with the mother's everyday functional living.4,5 This definition contrasts with the “baby blues,” which involves symptoms that appear and disappear within days after delivery, and postpartum psychosis, which is a rarer and much more extreme manifestation of depression.6,7 PPD may lead to long-term depressive illness in the new mother, as well as adversely affect the health and well-being of her partner and baby.8

Healthcare providers must be cognizant of the patterns of depression that can occur in the peripartum and postpartum time frame. In a recent meta-analysis of 23 longitudinal studies of PPD, the majority of studies showed that the severity of depression decreased over time,8 a finding consistent with the literature.9 Despite the evidence that the severity of depressive symptoms tends to decrease, patterns of depression are not homogenous among peripartum and postpartum women. Among depressed women, numerous studies have identified unique groups such as women with chronic major depression, women with chronic minor depression, and women who have recurrent or episodic depression.8 The risk factors that predict the onset and timing of depression among these women are heterogeneous.

The course of PPD can be heterogeneous as well, with some women experiencing resolution of symptoms, whereas others develop ongoing, increasingly severe, or episodic symptoms. Thus, researchers have called for studies that examine the role of known risk factors in studies of PPD.8

Numerous risk factors for developing PPD have been described in the literature. Prominent among these include a history of depression or anxiety, unstable or dissatisfied marital or relationship status, and inadequate social support.10 Additional risk factors that have been shown to impact the development of PPD include younger age,11,12 race/ethnicity,8,13 prepregnancy body mass index (BMI),14,15 lower educational status,11 lower socioeconomic status (SES),16 and health insurance status.17 The purpose of this study was to examine the role these various risk factors play in the trajectory of PPD.

Numerous studies have shown a history of depression or anxiety to be a risk factor for PPD.10,16,18–20 In 2013, Raisanen et al. reported that after adjustment for confounding variables, antenatal depression history was the strongest risk factor for PPD.19 Moreover, among Chinese women both antenatal depression and anxiety-prone personality were independent predictors of postnatal depression.10 However, in a 2014 literature review, Vliegen et al. found that many longitudinal studies of PPD did not investigate history of maternal depression, and called for future research to examine prepregnancy maternal mental health in greater detail.8

Marital status is also a key factor in the development of PPD. Risk for postnatal depression has been shown among women living without a partner and among women having a poorer quality of relationship with their present or recent partner.21 Higher postnatal depression scores were found among women who were single, separated, or noncohabiting than those who were married.22

Another key risk factor that contributes to the development of PPD is lack of social support. Social support from friends and relatives and partner support from the father of the baby are important and much anticipated sources of help for the new mother.23,24 During times of stress, support such as advice, help with chores and tasks, and emotional support has been shown to be a protective factor against the development of PPD,25 whereas women reporting little or no social support have an increased risk for developing PPD.2,16,21,26–31

In addition, although 11.5%–50% of women experiencing PPD report onset of depression before or during their pregnancy,32,33 few studies have examined whether women experiencing PPD have had a history of anxiety or depression, and whether depression is present during the peripartum period in addition to postpartum.8

Thus, in this study, we examine longitudinal patterns, or trajectories, of depression during the third trimester of pregnancy. We define our time frame to include data collected in the third trimester, before delivery, through a 1-year follow-up during the postpartum period. We further examine the association of risk factors in the development of those depression trajectories. Thus, one of the primary aims of this study is to examine PPD trajectories while including a peripartum time point, addressing a criticism in the literature that PPD reflects a vulnerability that occurs before pregnancy or delivery.34

Trajectory analysis has rarely been used in longitudinal studies of PPD,8 but has many benefits that commend its use for this study. Trajectory analysis can identify distinctive groups of individual trajectories within a large sample, estimate the shape of each trajectory, use these results to calculate the probability of membership in each trajectory, and determine the characteristics of individuals that make membership in each trajectory group likely.35 We hypothesize that women with a history of anxiety or depression, unmarried women, and women with lower social support are likely to have greater levels of depression than married women with more social support who do not have a history of anxiety or depression.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Data were gathered from The First Baby Study,36 in which 3006 women in Pennsylvania who were pregnant with their first baby and planning to deliver in Pennsylvania were surveyed. The design of this study has been previously described.36 In brief, women were recruited from participating hospitals throughout the state of Pennsylvania. Recruitment methods were designed to enroll women of varying socioecomonic status. Recruitment methods included placement of study materials such as brochures and flyers in venues likely to serve pregnant women such as hospitals, obstetricians' offices, and community health centers, as well as press releases, and direct recruitment at childbirth education classes.

Enrollment criteria for women included nulliparity, either English or Spanish speaking, and ages 18–35 years at the time of enrollment. All participants agreed to be interviewed once before delivery during the third trimester, and several times postdelivery. Interviews were conducted by trained interviewers via telephone. This study examines data from the third trimester (baseline) and at 1, 6, and 12 months postpartum. The study was reviewed and approved by the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The primary outcome variable was depressive symptoms as measured using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scores (EPDSs).37 The EPDS is a symptom-based screening scale. It is the most widely used instrument for screening for postnatal depression, and has been validated against clinical criteria, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuals III and IV, and across a number of different cultures, and found to have good sensitivity for detecting clinically significant PPD.38,39 The EDPS was administered at baseline during the third trimester of pregnancy, and at three time points postpartum: 1, 6, and 12 months. The EPDS is a validated 10-item self-report questionnaire designed to screen for postnatal depression.

Based on several pilot studies that we conducted among postpartum women in Pennsylvania, we found one item that women found confusing. This item was “Things have been getting on top of me,” with response options of “Yes, most of the time I haven't been able to cope at all,” Yes, sometimes I haven't been coping as well as usual,” “No, most of the time I have coped quite well,” and “No, I have been coping as well as ever.” The phrase “Things have been getting on top of me” is not commonly used in U.S. vernacular. Therefore, we changed that item to “I have had trouble coping.” We also changed the last item “The thought of harming myself has occurred to me” to “The thought of harming myself or others has occurred to me.” We changed this last item to include harming others because there have been instances of women who harmed their children during the postpartum period, including events that have been attributed to PPD. Both of these modified items exhibited very good corrected item-total correlations and the overall Cronbach's alpha was 0.81.

Participants were instructed to answer each question based on how they had felt within the previous 7 days. Each answer was scored on a scale of 0–3, with a score of 3 indicating the most severe depressive symptoms; thus total scores could range from 0 to 30. Higher total scores indicated worse depressive symptoms. We used a cut-off of 12 or greater indicating probable depression, as recommended in a systematic review of studies validating the EPDS.40

Key predictor variables were hypothesized to impact the patterns of depression; these include history of anxiety or depression, marital status, and social support. These variables were selected based on their association with postnatal depression in the literature.10,16,18,23–31,41 A history of anxiety or depression was measured in the baseline survey, which was given during the mother's third trimester. Patients were asked, “Before this pregnancy, had a doctor or other health care professional told you that you have any of the following health conditions…anxiety or depression?” This question has a high level of face validity, and was previously utilized in the Commonwealth Fund 1998 Survey of Women's Health42 and the Central Pennsylvania Women's Health Study (CePAWHS).43

Marital status was categorized as married, living with partner, not living with partner, and unattached. Participants were asked whether they had a partner or significant other, if they were married, and if they were currently living with their partner. These questions were used in CePAWHS.43

Social support was measured at baseline using five questions from the Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS), encompassing emotional, informational, tangible, and affectionate support, and positive social interaction. Response items were chosen from the original 19-item scale to reduce respondent burden. Women were asked, “Please tell me how often each of the following kinds of support are available to you: someone to confide in or talk to about your problems, someone to get together with for relaxation, someone to help you with daily chores if you are sick, someone to turn to for suggestions about how to handle a personal problem, someone to love and make you feel wanted.”44

Each question on the MOS-SSS is ranked on a scale of 1–5 (1 = felt support none of the time, 5 = felt support all of the time), equating to a total score ranging from 5 to 25. For one-way ANOVA, we used the following cut-offs to categorize women for social support: <15, 15–19, 20–24, and 25. In trajectory models, we used the numeric score. The MOS-SSS has been extensively validated in numerous populations, with increasing social support characterized by higher scores. In addition, reduced versions of the MOS-SSS including fewer items have also been validated and determined to have psychometric properties that indicate that they correlate well with the original full 36-item scale.45,46

We selected additional covariates for examination based on the literature, which also showed an association of these variables with PPD, but for which this association was less strong. These included age, race, prepregnancy BMI, education, poverty status, type of insurance, intimate partner violence, and use of antidepressants. Age was included because some studies have shown depressed mothers were slightly younger than their nondepressed counterparts,11,12 whereas others reported no association.8 Race/ethnicity was included because studies have found mixed results regarding the association between race and PPD.8,13 Due to small cell sizes in the racial and ethnic categories that were nonwhite, we dichotomized this variable into white and nonwhite. BMI was included because some studies have shown an association between depressive symptoms and higher prepregnancy BMI.14,15

Educational status was included because some previous studies have shown a correlation between lower educational level and chronic PPD,11 whereas others showed no association between educational status and PPD.47 Poverty status was included because lower SES has been shown to increase a woman's risk for PPD.16 Poverty was calculated based on household size and income. For mothers who had missing responses to the poverty variable, the response to the question, “Do you have difficulty paying for basic needs?” was used; responses of “a lot of trouble” were specified as “poverty,” “some trouble” as “near poverty,” and all other responses as “nonpoverty.”

Insurance status was examined as an additional descriptor of SES. All categorical variables selected for examination were classified to ensure a minimum of 150 events in each category (5% of the total sample size). Thus, although we considered including intimate partner violence (n = 57, 1.9%) and antidepressant use (n = 72, 2.4%) as additional covariates, these were removed due to low prevalence.

Data analysis

We first reported descriptive characteristics of the cohort for each time point. One-way ANOVA models were used to test for differences among EPDSs for each variable at each time point. We then used a semiparametric mixture model to identify distinct clusters of depression trajectories over time within our cohort. EPDSs at each time comprised our outcome variable. We assumed that EPDSs arose from a censored normal distribution, in which scores ranged from 0 to 30. The time points were coded as 0 for baseline (third trimester, before delivery), and 1, 6, and 12 for the respective month postpartum. The mixture model required two inputs: the number of distinct trajectory groups to fit and the allowable functional form for each trajectory group. We fit models that varied the number of distinct groups from 3 to 8 and specified that only quadratic trajectories (or less) were allowed. Proc Traj (SAS System 9.3) was used to fit all models.48

We used Aikaike's information criterion (AIC),49 a means for model selection that balances goodness of fit and model complexity, to determine the number of groups in the model. AIC favored the largest model that contained eight trajectories, but the smallest trajectory group contained only an estimated 0.1% of mothers in the cohort (N = 3). Therefore, the model was discarded. The smallest group for the model with seven distinct trajectories contained only 0.7% of mothers (N = 21), and models that adjusted for mother characteristics (age, marital status, and social support) would not converge with seven groups. Thus, we chose six groups as our final trajectory model. We evaluated model fit using three diagnostic measures: entropy, average posterior probabilities for each group for patients assigned to that group, and odds of correct classification. Nagin50 indicates a rule of thumb that average posterior probabilities should be >0.7 and odds of correct classification should be >5 for all groups.

We extended our six-group model by including maternal characteristics as risk factors for trajectory group membership. This extended model allowed us to examine how variables such as age, marital status, or social support affected the probability of belonging to each of the six distinct trajectory groups. Age and social support were treated as continuous variables in these models. The extension constituted a multinomial logit model, in which the log odds of group membership were modeled as a function of risk factors included in the model.

In this extended model, we examined only those maternal characteristics related to our hypothesized primary predictors (a history of anxiety/depression, marital status, and social support) and those covariates that were associated with postpartum depressive symptoms in one-way ANOVA models: age, race, education, poverty status, and health insurance. Because prepregnancy BMI was not associated with depression at any time point, it was not included in the extended trajectory models.

We imputed missing values for age (N = 6), marital status (N = 1), and social support (N = 3) at their median values for use in the extended model. To achieve convergence, the extended model that included all prespecified covariates required us to force three of the six groups to have linear trajectories, which was sensible because a quadratic trend did not yield a significant p value for these three groups.

Due to the number of parameters in the model and the small number estimated to belong to some trajectory groups, we aimed to find a parsimonious model. From the model that included all prespecified covariates, age, race, poverty status, and health insurance were all highly nonsignificant (p > 0.30) and were dropped from the model. Among the remaining four variables (history of anxiety and depression, marital status, social support, and education), we fit all possible subsets (16 models total) and selected the model with the lowest value of AIC. AIC favored a model that included only our three hypothesized primary predictor variables: history of anxiety and depression, social support score, and marital status.

We specified a priori that the group with the lowest overall depression score would be the reference category, reasoning that the lowest overall depression was the most clinically relevant comparator. Thus, with trajectory group 1 as the reference group, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each variable were reported. We also reported estimated probabilities of group membership from this model.

Results

A total of 3006 mothers enrolled in the study. All mothers completed the EPDS in the baseline survey, 3005 (>99%) mothers completed EPDS in the 1-month survey, 2911 mothers (97%) completed the EPDS in the 6-month survey, and 2802 (93%) completed the EPDS in the 12-month survey. At baseline, 8.52% had EPDSs of 12 or higher. At 1 month postpartum, 5.06% had EPDSs of 12 or higher; at 6 months postpartum 4.92% had EPDSs of 12 or higher and at 12 months postpartum, 4.79% had EPDSs of 12 or higher. Overall, 16.00% of the women had an EPDS score at 12 or above at least once during the four measured time points.

Table 1 shows the results of one-way ANOVA models used to test for differences in EPDS for each variable at each time point. Younger women (≤20 years) had higher EPDSs, indicating greater depression at baseline (mean 7.5, SD 5.0), 6 months (mean 5.2, SD 4.9), and 12 months (mean 5.2, SD 4.8) than older women (>30 years) at baseline (mean 5.4, SD 3.5), 6 months (mean 4.2, SD 3.5), and 12 months (mean 4.3, SD 3.6). At these same time points, women who were not living with their partner or who were unattached also reported higher EPDSs than women who were attached or who were living with their partner.

Table 1.

Summary of Baseline Variables and Their Association with Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scores at Each Time Point

| EPDS, mean (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 3006), N (%) | Baseline (N = 3006) | 1 month (N = 3005) | 6 months (N = 2911) | 12 months (N = 2802) | |

| Age | p < 0.001 | p = 0.002 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| ≤20 | 346 (11.5) | 7.5 (5.0) | 4.5 (4.9) | 5.2 (4.9) | 5.2 (4.8) |

| 21–25 | 709 (23.6) | 6.2 (4.0) | 4.0 (3.6) | 4.2 (3.8) | 4.4 (4.1) |

| 26–30 | 1322 (44.1) | 5.5 (3.6) | 4.4 (3.6) | 3.8 (3.5) | 4.0 (3.5) |

| >30 | 623 (20.8) | 5.4 (3.5) | 4.7 (3.8) | 4.2 (3.5) | 4.3 (3.6) |

| Race | p < 0.001 | p = 0.42 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| Nonwhite | 504 (16.8) | 7.0 (4.7) | 4.5 (4.7) | 4.8 (4.6) | 5.0 (4.7) |

| White | 2502 (83.2) | 4.7 (3.7) | 4.4 (3.6) | 4.0 (3.6) | 4.1 (3.7) |

| Prepregnancy BMI | p = 0.87 | p = 0.51 | p = 0.61 | p = 0.91 | |

| Normal/underweight | 1717 (57.2) | 5.9 (3.9) | 4.4 (3.9) | 4.1 (3.8) | 5.0 (4.7) |

| Overweight/obese | 1287 (42.8) | 5.9 (4.0) | 4.3 (3.8) | 4.2 (3.8) | 4.1 (3.7) |

| Marital status | p < 0.001 | p = 0.52 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| Married | 2117 (70.4) | 5.4 (3.4) | 4.4 (3.6) | 3.9 (3.4) | 4.0 (3.5) |

| Living with partner | 544 (18.1) | 6.5 (4.4) | 4.2 (4.2) | 4.5 (4.2) | 4.8 (4.3) |

| Not living with partner | 187 (6.2) | 7.4 (4.7) | 4.4 (4.4) | 5.2 (5.0) | 5.5 (4.9) |

| Unattached | 157 (5.2) | 8.4 (5.3) | 4.7 (4.8) | 5.4 (4.8) | 5.8 (5.0) |

| Education | p < 0.001 | p = 0.07 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| High school or less | 501 (16.7) | 7.0 (4.8) | 4.2 (4.4) | 4.7 (4.6) | 5.0 (4.8) |

| Some college or technical | 804 (26.7) | 6.3 (4.1) | 4.2 (3.9) | 4.4 (4.1) | 4.5 (4.1) |

| College graduate or higher | 1701 (56.6) | 5.4 (3.5) | 4.5 (3.6) | 3.9 (3.3) | 4.0 (3.4) |

| Poverty status | p < 0.001 | p = 0.19 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| Poverty | 251 (8.3) | 7.4 (5.3) | 4.7 (4.9) | 5.4 (5.0) | 5.3 (4.7) |

| Near poverty | 311 (10.3) | 7.0 (4.4) | 4.6 (4.3) | 4.6 (4.2) | 5.2 (4.4) |

| Nonpoverty | 2444 (81.3) | 5.6 (3.7) | 4.3 (3.6) | 4.0 (3.5) | 4.1 (3.7) |

| Insurance | p < 0.001 | p = 0.89 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| Public/self | 698 (23.2) | 7.1 (4.9) | 4.4 (4.5) | 5.0 (4.6) | 5.3 (4.7) |

| Private | 2308 (76.8) | 5.5 (3.5) | 4.4 (3.6) | 3.9 (3.5) | 4.0 (3.6) |

| Social support score | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| <15 | 72 (2.4) | 9.7 (5.9) | 6.3 (5.0) | 6.8 (5.2) | 7.0 (5.5) |

| 15–19 | 438 (14.6) | 7.6 (4.1) | 5.8 (4.3) | 5.8 (4.2) | 5.8 (4.2) |

| 20–24 | 1613 (53.7) | 5.8 (3.7) | 4.5 (3.6) | 4.2 (3.7) | 4.2 (3.6) |

| 25 | 880 (29.3) | 4.9 (3.5) | 3.2 (3.4) | 3.0 (3.1) | 3.3 (3.6) |

| History of anxiety or depression | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| No | 2318 (77.1) | 5.4 (3.7) | 4.0 (3.5) | 3.6 (3.4) | 3.8 (3.5) |

| Yes | 688 (22.9) | 7.6 (4.4) | 5.7 (4.4) | 5.9 (4.4) | 6.0 (4.3) |

BMI, body mass index; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scores.

At all four time points, women with a social support scale score <15 had a significantly higher EPDS than women who had scores 15–19, 20–24, and 25. Women with a history of anxiety or depression had significantly higher EPDS at baseline (mean 7.6, SD 4.4), 1 month (mean 5.7, SD 4.4), 6 months (mean 5.9, SD 4.4), and 12 months (mean 6.0, SD 4.3) than women who did not have a history of anxiety or depression at baseline (mean 5.4, SD 3.7), 1 month (mean 4.0, SD 3.5), 6 months (mean 3.6, SD 3.4), and 12 months (mean 3.8, SD 3.5).

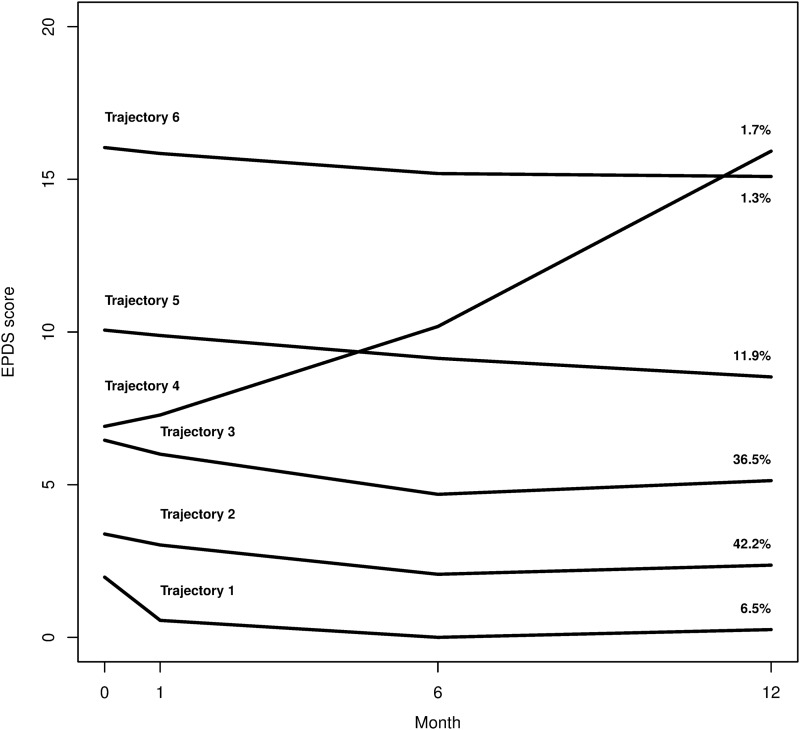

Figure 1 depicts the estimated trajectories from the six-group trajectory model. Model diagnostics indicated good fit, with entropy of 0.81, average posterior probabilities ranging from 0.77 (group 1) to 0.88 (group 6), and the lowest odds of correct classification being 6.2 (group 2). Trajectories that fall lower on the y-axis reflect lower overall depression scores, whereas trajectories that fall higher on the y-axis reflect higher overall depression scores. Trajectories were labeled 1 to 6 according to the estimated value during the third trimester.

FIG. 1.

Estimated Trajectories of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scores (EPDS) by group.

All trajectories were stable, or slightly decreasing, except for trajectory 4 that showed an increase over time. A total of 85.2% of mothers belonged to the three lowest trajectories, which indicated the lowest levels of depression. The estimated proportion of mothers who belonged to trajectory 4 was 1.7%. Women who followed trajectory 4 were nondepressed at baseline with an EPDS of ∼7, similar to women belonging to trajectory 3, yet at 12 months they had an EPDS >15, similar to clinically depressed women in trajectory 6.

Table 2 reports estimated ORs of trajectory group membership (with trajectory group 1, the least depressed group, as the reference group) for the model that adjusted for history of anxiety or depression, social support, and marital status. The model indicates that compared with women with no history of anxiety of depression, women with a history of anxiety or depression had 7.9 times higher odds of belonging to group 4 (95% CI 3.6–17.4), 10.8 times higher odds (95% CI 6.3–18.5) of belonging to group 5, and 18.5 times higher odds (95% CI 7.6–45.1) of belonging to group 6, all compared with group 1.

Table 2.

Estimated Odds Ratios for Trajectory Group Membership (Reference: Group 1)

| Trajectory Group 2 | Trajectory Group 3 | Trajectory Group 4 | Trajectory Group 5 | Trajectory Group 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI |

| History of anxiety or depression | 1.98 | 1.22–3.23 | 4.53 | 2.79–7.38 | 7.92 | 3.59–17.4 | 10.8 | 6.26–18.5 | 18.5 | 7.58–45.1 |

| No history of anxiety or depression (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| MOS scale, 1-point increase | 0.72 | 0.66–0.80 | 0.63 | 0.57–0.69 | 0.64 | 0.56–0.74 | 0.58 | 0.52–0.64 | 0.51 | 0.45–0.58 |

| Married (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Living with partner | 0.56 | 0.38–0.82 | 0.69 | 0.46–1.02 | 1.03 | 0.35–2.98 | 1.19 | 0.68–2.09 | 3.11 | 1.11–8.74 |

| Not living with partner | 0.83 | 0.43–1.59 | 0.84 | 0.41–1.71 | 7.82 | 3.08–19.8 | 2.93 | 1.29–6.63 | 5.95 | 1.3–27.36 |

| Unattached | 0.61 | 0.28–1.31 | 1.23 | 0.61–2.48 | 2.02 | 0.47–8.72 | 1.79 | 0.74–4.32 | 8.60 | 2.5–29.57 |

Bold values are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Trajectory Group 1 reference.

MOS, Medical Outcomes Study.

Compared with married women, women who were unattached had 8.6 times higher odds (95% CI 2.5–29.6) of belonging to group 6 than to group 1; women who were not living with a partner had 2.9 times higher odds (95% CI 1.3–6.6) of belonging to group 5 than to group 1, and women who were not partnered had 7.8 higher odds (95% CI 3.1–19.8) of belonging to group 4 than to group 1. As anticipated, higher social support scores were associated with lower odds of membership in higher depression trajectories. For example, the model indicated that for every one point increase in social support score, the odds of belonging to trajectory 6 were 50% lower (OR = 0.5, 95% CI 0.45–0.58) relative to trajectory 1.

Table 3 shows the estimated probabilities of group membership as a function of specific risk factors as calculated from the model. A mother who had no risk factors [i.e., no history of anxiety or depression, a high social support score (25), and was married] had a probability of 30% of belonging to trajectory group 1, the lowest depression trajectory, and a low probability (0.04%) of belonging to trajectory group 6, the highest depression trajectory.

Table 3.

Estimated Probabilities of Trajectory Group Membership from Model

| Risk factors | Trajectory group (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | History of anxiety or depression | Social support score | Marital status | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 0 | No | High (25) | Married | 30 | 53 | 15 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.04 |

| 1 | Yes | High (25) | Married | 13 | 47 | 29 | 2 | 9 | 0.4 |

| 1 | No | Low (20) | Married | 6 | 56 | 31 | 1 | 6 | 0.3 |

| 1 | No | High (25) | Living with partner | 41 | 41 | 14 | 0.9 | 3 | 0.2 |

| 1 | No | High (25) | Not living with partner | 31 | 45 | 13 | 5 | 6 | 0.3 |

| 1 | No | High (25) | Unattached | 35 | 38 | 21 | 2 | 4 | 0.4 |

| 2 | Yes | Low (20) | Married | 2 | 33 | 41 | 3 | 19 | 2 |

| 2 | Yes | High (25) | Living with partner | 18 | 36 | 27 | 3 | 14 | 2 |

| 2 | Yes | High (25) | Not living with partner | 11 | 32 | 20 | 15 | 21 | 2 |

| 2 | Yes | High (25) | Unattached | 13 | 28 | 36 | 4 | 15 | 3 |

| 2 | No | Low (20) | Living with partner | 9 | 46 | 31 | 2 | 11 | 1 |

| 2 | No | Low (20) | Not living with partner | 6 | 43 | 24 | 9 | 16 | 2 |

| 2 | No | Low (20) | Unattached | 7 | 36 | 41 | 3 | 11 | 3 |

| 3 | Yes | Low (20) | Living with partner | 2 | 23 | 36 | 4 | 29 | 6 |

| 3 | Yes | Low (20) | Not living with partner | 1 | 18 | 23 | 15 | 37 | 6 |

| 3 | Yes | Low (20) | Unattached | 1 | 16 | 40 | 5 | 27 | 11 |

Probabilities do not necessarily sum to 1 for all rows due to rounding error.

This is in contrast to a mother with all three risk factors [i.e., history of anxiety or depression, inadequate social support score (20), and unattached marital status] who had a low probability (1%) of belonging to trajectory group 1 compared with a relatively higher probability of (11%) of belonging to trajectory group 6. Thus, a mother with these three risk factors had a substantially higher probability of belonging to the trajectory group that was always depressed (11% compared with 0.04%) relative to a mother with no risk factors.

Discussion

This study analyzed patterns of PPD and risk factors predisposing women to depression for a large sample of 3006 women. We found that most women tended to remain at the same level of depression, or became slightly less depressed during the postpartum period with the differences between curves largely driven by the baseline value of depression; this is consistent with prior studies.8,9 The three lowest trajectories (1–3), which started and remained nondepressed, accounted for 85.2% of the participants, signifying that depression was not an emerging problem for the large majority of first-time mothers.

As hypothesized, women with a history of anxiety or depression, single marital status, and inadequate social support had the highest likelihood of belonging to the trajectories representing the most depressed groups. A small minority of women (1.7%) were not depressed at baseline during their third trimester, but developed depression during the postpartum period. These women had EPDSs similar to nondepressed women who belonged to trajectory group 3 at baseline, but by 6 months postpartum became clinically depressed and had similar EPDSs to trajectory groups 5 and 6.

Of note, the risk factor profile of members of trajectory 4 was more similar to the risk factor profiles of members of the higher order (thus more depressed) trajectories, than risk factor profiles of members of trajectories 1–3. This suggests that even among women who are nondepressed during the third trimester, the risk factors predicting PPD are similar to the risk factors of those who are depressed before delivery.

Our study has several strengths. First we used a much larger sample than has been used in most prior studies. Thus we were able to identify a small minority of women with a trajectory of significantly increasing depressive symptoms who remain depressed at 1 year postpartum. To our knowledge, this trajectory is not commonly described in the literature. Although small, this sample of women with emergent PPD bears further consideration.

In addition to the risk factors for emergent depression identified in our study (history of depression or anxiety, inadequate social support, and lack of stable attachment to a partner), there are likely additional factors that were unmeasured in our study but distinguish this group from women who do not present with emergent depression. These factors may include peripartum or delivery complications,51 significant stressful life events that occur in the postpartum period unmeasured in this study,52 and variation in the hormonal milieu between depressed and nondepressed postpartum women.53

Moreover, in response to a literature gap identified in a recent review,8 we included a history of prepregnancy depression in our models and included an objective measurement of peripartum depression, thus allowing for the determination of emerging depression postpartum. In addition, we identified key factors that clinicians might use to help them determine the risk for both higher levels of PPD and emerging depression in the postpartum period.

The inclusion of several time points postpartum was a strength of this study. Had our study included only the first two time points at baseline and 1 month postpartum, worsening depression for women belonging to trajectory 4 would not have been appreciated, nor the overall trend of decreasing depression seen in all other trajectories. Lastly, the methodology of trajectory analysis has not been commonly used to examine patterns of PPD, and allows several advantages over the more common technique of analyzing data sequences. As detailed by Nagin,35 these advantages include the capability to identify, rather than assume, distinctive trajectory groups, the ability to estimate the proportions in each trajectory group, and the ability to relate trajectory group membership to key covariates.

Potential limitations to consider include the limited generalizability of the sample. The participants tended to be more educated and of higher SES than other women at first childbirth in the state of Pennsylvania as a whole.36 This may be due to response bias, in which middle class people are more likely to participate in surveys and studies than individuals with a lower SES.54

An equally important limitation was the inability to fully discriminate between a broad range of racial and ethnic categories, due to small cell sizes among nonwhite participants. Thus, our data may not be generalizable to cohorts who are more racially and ethnically diverse.

Another limitation is the relatively low percentage of women scoring at 12 or above on the EPDS at each of the three postpartum data collection stages (around 5%) in comparison with previous studies that have generally reported rates of 10%–15%.55 We suspect that the lower rate of PPD that we found in this study is due, in part, to the higher SES of our study participants and, in part, to our method of data collection (telephone interview). It may be that the study participants tended to minimize their depression symptoms when queried by telephone interview, for reasons of social desirability. A large-scale population study to measure prevalence of anxiety and depression in Norway found two to three times the rate of probable cases of psychological distress among those who completed self-administered questionnaires in comparison with those interviewed by telephone or in person.56

In addition, the modification of the reduced scale of the MOS-SSS used in our study has face validity, but has not been formally validated against reference standards. Finally, our models included only variables that occurred before delivery, and, therefore, delivery complications were by definition excluded from our analyses. However, perinatal complications do increase the risk of PPD.51 Therefore, future longitudinal analyses should include delivery complications as a likely predictor of PPD.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight a need for further awareness of risk factors that may predispose women to become depressed during the postpartum period and the implementation of early intervention strategies. Prior studies have supported the idea of home visits and further education for mothers with inadequate social support and who are not married to provide women with support before their delivery31,41 with the aim that these efforts may reduce the incidence of depression among first-time mothers. Our data support this focus on increasing social support to reduce depression among first-time mothers.

Indeed, promising models exist indicating that home visitation by nurses may decrease the severity of PPD,57 with some authors arguing that nursing home visits could provide a “safety net” that can be incorporated into clinical practice for new mothers at risk for PPD. This is supported by qualitative evidence that new mothers identify instrumental social support as essential to both physical and emotional recovery.58 However, more research is necessary to improve the structure of home visitation as a buffer against PPD. A recent Cochrane review suggested that home visits did not provide strong evidence of improvements in maternal mental health, and that further study on the timing and frequency of home visits, as well as tailoring the home visit schedule to the needs of the community, is necessary for home visitation to research its potential as a mitigator of PPD among at-risk new mothers.59

Our findings indicate a need for clinicians to be aware of the key predictors of PPD highlighted in our study. Single women, women with inadequate social support, and women with a history of depression or anxiety are at high risk for the development of PPD, even if they are nondepressed in the peripartum period. These women should be screened at multiple points in the first year of postpartum to determine whether they manifest emerging depression. The challenges that this strategy poses are significant, as prior studies have not conclusively shown the benefit of a PPD screening program.60,61

Successful depression screening programs require intense, onsite treatment,62,63 which may not be realistic in a current busy practice environment. Moreover, a mother's interaction with her obstetrician is often terminated after a 6-week postpartum visit, which may be too early to detect emerging depression.64 This has led to calls for pediatricians, who are likely to have far greater contact with mothers at risk for depression, to be at the forefront of this screening process. The American Academy of Pediatrics echoes this recommendation,65 and has advocated for more research and streamlined payment systems to allow this option.

Regardless, our data support the need for further awareness of risk factors that may predispose women to PPD. The goal of this greater awareness would be to produce appropriate, targeted, early clinical intervention for women who have multiple risk factors for PPD, potentially preventing the morbidity associated with maternal PPD for mother, child, and family.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the support of this research by a grant R01-HD052990 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, USA.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Wisner KL, Sit DK, McShea MC, et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:490–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression-a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 1996;8:37–54 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson GE, Stewart DE. Postpartum disorders. In: Stotland NL, Stewart DE, eds. Psychological aspects of women's healthcare. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Press, Inc., 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4 ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remick RA. Diagnosis and management of depression in primary care: A clinical update and review. CMAJ 2002;167:1253–1260 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennerley H, Gath D. Maternity blues. I. Detection and measurement by questionnaire. Br J Psychiatry 1989;155:356–362 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brockington IF, Cernik KF, Schofield EM, Downing AR, Francis AF, Keelan C. Puerperal psychosis. Phenomena and diagnosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38:829–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vliegen N, Casalin S, Luyten P. The course of postpartum depression: A review of longitudinal studies. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2014;22:1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray L, Cooper PJ, Stein A. Postnatal depression and infant development. BMJ 1991;302:978–979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siu BW, Leung SS, Ip P, Hung SF, O'Hara MW. Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: A prospective study of Chinese women at maternal and child health centres. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell SB, Brownell CA, Hungerford A, Spieker SI, Mohan R, Blessing JS. The course of maternal depressive symptoms and maternal sensitivity as predictors of attachment security at 36 months. Dev Psychopathol 2004;16:231–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornish AM MC, Ungerer JA. Postnatal depression and the quality of mother-infant interactions during the second year of life. Aust J Psychol 2008;60:142–151 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howell EA, Mora PA, DiBonaventura MD, Leventhal H. Modifiable factors associated with changes in postpartum depressive symptoms. Arch Womens Ment Health 2009;12:113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beck CT. State of the science on postpartum depression: What nurse researchers have contributed-part 2. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2008;33:151–156; quiz 157–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisman O, Granat A, Gilboa-Schechtman E, et al. The experience of labor, maternal perception of the infant, and the mother's postpartum mood in a low-risk community cohort. Arch Womens Ment Health 2010;13:505–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: An update. Nurs Res 2001;50:275–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Committee on Obstetric Pratice. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion no. 630. Screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:1268–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Hara MW SA. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—A meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 1996;8:37–54 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raisanen S, Lehto SM, Nielsen HS, Gissler M, Kramer MR, Heinonen S. Fear of childbirth predicts postpartum depression: A population-based analysis of 511 422 singleton births in Finland. BMJ Open 2013;3:e004047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watson JP, Elliott SA, Rugg AJ, Brough DI. Psychiatric disorder in pregnancy and the first postnatal year. Br J Psychiatry 1984;144:453–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ludermir AB, Lewis G, Valongueiro SA, de Araujo TV, Araya R. Violence against women by their intimate partner during pregnancy and postnatal depression: A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2010;376:903–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bacchus L, Mezey G, Bewley S. Domestic violence: Prevalence in pregnant women and associations with physical and psychological health. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2004;113:6–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gremigni P, Mariani L, Marracino V, Tranquilli AL, Turi A. Partner support and postpartum depressive symptoms. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2011;32:135–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Misri S, Kostaras X, Fox D, Kostaras D. The impact of partner support in the treatment of postpartum depression. Can J Psychiatry 2000;45:554–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brugha TS, Sharp HM, Cooper SA, et al. The Leicester 500 Project. Social support and the development of postnatal depressive symptoms, a prospective cohort survey. Psychol Med 1998;28:63–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glasser S, Barell V, Boyko V, et al. Postpartum depression in an Israeli cohort: Demographic, psychosocial and medical risk factors. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2000;21:99–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inandi T, Elci OC, Ozturk A, Egri M, Polat A, Sahin TK. Risk factors for depression in postnatal first year, in eastern Turkey. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1201–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Surkan PJ, Peterson KE, Hughes MD, Gottlieb BR. The role of social networks and support in postpartum women's depression: A multiethnic urban sample. Matern Child Health J 2006;10:375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ege E, Timur S, Zincir H, Geckil E, Sunar-Reeder B. Social support and symptoms of postpartum depression among new mothers in Eastern Turkey. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2008;34:585–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao LL, Chan SW, Mao Q. Depression, perceived stress, and social support among first-time Chinese mothers and fathers in the postpartum period. Res Nurs Health 2009;32:50–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leahy-Warren P, McCarthy G, Corcoran P. First-time mothers: Social support, maternal parental self-efficacy and postnatal depression. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:388–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stowe ZN, Hostetter AL, Newport DJ. The onset of postpartum depression: Implications for clinical screening in obstetrical and primary care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:522–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yonkers KA, Ramin SM, Rush AJ, et al. Onset and persistence of postpartum depression in an inner-city maternal health clinic system. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1856–1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riecher-Rössler A, Hofecker Fallahpour M. Postpartum depression: Do we still need this diagnostic term? Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2003;108:51–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychol Methods 1999;4:139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kjerulff KH, Velott DL, Zhu J, et al. Mode of first delivery and women's intentions for subsequent childbearing: Findings from the First Baby Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2013;27:62–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zubaran C, Schumacher M, Roxo M, Foresti K. Screening tools for postpartum depression: Validity and cultural dimensions. Afr J Psychiatry 2010;13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Tambs K, Opjordsmoen S, Ove Samuelsen S. Review of validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001;104:243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, Price J, Gray R. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009;119:350–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie RH, He G, Koszycki D, Walker M, Wen SW. Prenatal social support, postnatal social support, and postpartum depression. Ann Epidemiol 2009;19:637–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karen Scott Collins CS, Joseph Susan, et al. Health Concerns Across a Woman's Lifespan: The Commonwealth Fund 1998 Survey of Women's Health. The Commonwealth Fund May 1999

- 43.Downs DS, Feinberg M, Hillemeier MM, et al. Design of the Central Pennsylvania Women's Health Study (CePAWHS) strong healthy women intervention: Improving preconceptional health. Matern Child Health J 2009;13:18–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:705–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holden L, Lee C, Hockey R, Ware RS, Dobson AJ. Validation of the MOS Social Support Survey 6-item (MOS-SSS-6) measure with two large population-based samples of Australian women. Qual Life Res 2014;23:2849–2853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moser A, Stuck AE, Silliman RA, Ganz PA, Clough-Gorr KM. The eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey: Psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:1107–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ashman SB, Dawson G, Panagiotides H. Trajectories of maternal depression over 7 years: Relations with child psychophysiology and behavior and role of contextual risks. Dev Psychopathol 2008;20:55–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res 2001;29:374–393 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Autom Control 1974;19:716–723 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagin DS. Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blom EA, Jansen PW, Verhulst FC, et al. Perinatal complications increase the risk of postpartum depression. The generation R study. BJOG 2010;117:1390–1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eberhard-Gran M, Tambs K, Opjordsmoen S, Skrondal A, Eskild A. Depression during pregnancy and after delivery: A repeated measurement study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 2004;25:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abou-Saleh MT, Ghubash R, Karim L, Krymski M, Bhai I. Hormonal aspects of postpartum depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1998;23:465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Warriner GK, Miller S. Evaluating socio-economic status (SES) bias in survey nonresponse. J Off Stat 2002;18:1 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Halbreich U, Karkun S. Cross-cultural and social diversity of prevalence of postpartum depression and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord 2006;91:97–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moum T. Mode of administration and interviewer effects in self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression. Soc Indic Res 1998;45:279–318 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Horowitz JA, Murphy CA, Gregory K, Wojcik J, Pulcini J, Solon L. Nurse home visits improve maternal/infant interaction and decrease severity of postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2013;42:287–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Negron R, Martin A, Almog M, Balbierz A, Howell EA. Social support during the postpartum period: Mothers' views on needs, expectations, and mobilization of support. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:616–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yonemoto N, Dowswell T, Nagai S, Mori R. Schedules for home visits in the early postpartum period. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;7:CD009326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leung SS, Leung C, Lam TH, et al. Outcome of a postnatal depression screening programme using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: A randomized controlled trial. J Public Health 2011;33:292–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yonkers KA, Smith MV, Lin H, Howell HB, Shao L, Rosenheck RA. Depression screening of perinatal women: An evaluation of the healthy start depression initiative. Psychiatr Serv 2009;60:322–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Georgiopoulos AM, Bryan TL, Yawn BP, Houston MS, Rummans TA, Therneau TM. Population-based screening for postpartum depression. Obstet Gynecol 1999;93(5 Pt 1):653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gilbody S, Sheldon T, House A. Screening and case-finding instruments for depression: A meta-analysis. CMAJ 2008;178:997–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liberto TL. Screening for depression and help-seeking in postpartum women during well-baby pediatric visits: An integrated review. J Pediatr Health Care 2012;26:109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Earls MF. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics 2010;126:1032–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]