Summary

The past decade witnessed rapid development of novel drugs and therapeutic biological agents. The marketing authorization for novel therapies is often time consuming and distressing for patients. Earlier clinical trials were the only way to access new drugs under development. However, not every patient meets the enrolment criteria, and participation is difficult for patients with life-threatening, long-lasting or seriously debilitating diseases like rare diseases. Early access programs like “Compassionate Use Program (CUP)” have generated alternative channels for such patients. The European Medical Agency provides regulations and recommendations for compassionate use, upon which every European Union (EU) member state has developed its own rules and regulations. Despite previous reviews and studies, the available information is limited and gaps exist. This literature review explores CUP in 28 EU member states. Data was collected through literature review and use of country-specific search terms from the healthcare domain. Data sources were not limited to databases and articles published in journals, but also included grey literature. The results implied that CUP was present in 20 EU member states (71%). Of 28 EU states, 18 (∼64%) had nationalized regulations and processes were well-defined. Overall, this review identified CUP and its current status and legislation in 28 EU member states. The established legislation for CUP in the EU member states suggest their willingness to adopt processes that facilitate earlier and better access to new medicines. Further research and periodic reviews are warranted to understand the contemporary and future regulatory trends in early access programs.

Keywords: Compassionate use, early access, special access, rare diseases, orphan drugs, European Union, European Union member states

1. Introduction

The past decade has seen rapid development in the field of novel drugs and therapeutic biological agents. Despite the remarkable innovations that took place in the field of novel therapeutics, marketing authorization for promising novel therapies is time consuming, which can be at times distressing for some patients, particularly, those with severe diseases (1). This implies a serious bearing on the overall quality of life in such patients, because treatment can be challenging and at times inadequate with currently authorized medicines (1). Hence, new drugs that are unauthorized or in the late phase of clinical trials are the only hope for a plausible successful treatment in such patients.

In the past, clinical trials were the only way for patients in many countries to access drugs under development (2). However, clinical trials are time-consuming and expensive, and not every patient meets enrolment criteria for specific clinical trials (1). Also, participation in clinical trials is a difficult choice for patients with life-threatening, long-lasting or seriously debilitating diseases. Nonetheless, in recent times, early access programs have opened doors to more possibilities for such patients, of which “Compassionate Use Program (CUP)” is one. There are approximately 7,000 different types of rare diseases (3). Globally, it is estimated that approximately 350 million people suffer from rare diseases of which around 8.6% are from Europe (3). Since 2010, the number of compassionate use requests has risen by nearly 25% and a major proportion of these requests are from rare disease patient populations, owing to highly engaged patients and caregivers connected to advocacy groups (4). Many pharmaceutical companies are developing new therapies for patients with rare, life-threatening genetic diseases and are also facilitating access to such drugs (5). Lately, Genzyme Corporation has donated imiglucerase to hundreds of severely affected patients with Gaucher's disease in three large-scale international CUP (6,7). Such efforts by pharma majors to improve early access to life-threatening disease drugs makes it essential to understand CUP and the processes involved.

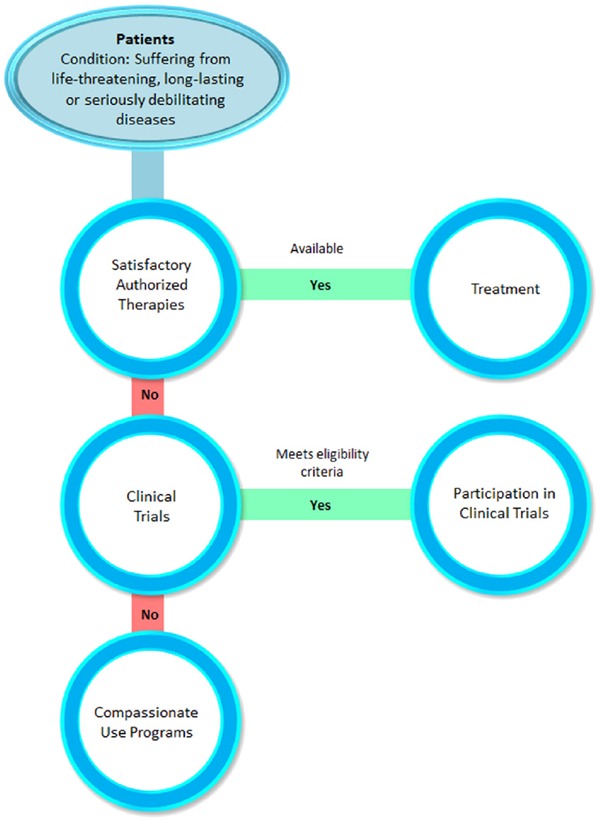

CUP are early access programs intended to facilitate the availability of new medicines to patients suffering with life threatening disorders or diseases in the EU member states (Figure 1) (6). In general, CUP are considered in the early stages of the product development cycle where patients get pre-launch access to the investigational drugs or drugs not yet authorized in the country. Unlike clinical trials, which are protocol driven and where participants have to meet certain inclusion and exclusion criteria, CUP allows patients without considering any criteria. But, CUP enrolls patients as per the laws and regulations outlined for the program (2). The European Medicines Agency (EMA) defines “compassionate use” as a treatment option that allows the use of an unauthorized medicinal product which is under development (8).

Figure 1.

Pathway to compassionate use program. This figure depicts the pathway to access new medicines through compassionate use program for a patients suffering from severe or enervating diseases.

The EMA provides recommendations for compassionate use through the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Also, laws and regulations are set by the EMA for compassionate use in the European Union (EU) (Table 1) (8–11). Every EU member state has developed its own legislation for CUP based on the EMA recommendations and legal framework. Therefore, it is necessary for stakeholders such as, health professionals, patients and patient organizations, pharmaceutical companies and policy makers to be informed of legislation and processes that facilitate or gain access to innovative medicines at the earliest.

Table 1. Laws and regulations set by the European Medical Agency for compassionate use in the European Union (Ref. 9).

| Article 6 of Directive 2001/83/EC1 of the EU requires that medicinal products be authorized before they are marketed in a community. Previously, a clinical trial was the only option for using unauthorized medicinal products. However, CUP created a treatment option for patients in the EU suffering from a disease without existing satisfactory authorized therapy alternatives or who could not be part of a clinical trial. The EMA recommends compassionate use through the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) and a legal framework. |

| Article 83 (1) of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 introduces the legal framework for compassionate use in the EU for medicinal products eligible to be authorized via the Centralized Procedure, stating that “By way of exemption from Article 6 of Directive 2001/83/EC, MS may make a medicinal product for human use belonging to the categories referred to in Article 3(1) and 3(2) of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 available for compassionate use”. |

Despite the availability of previous reviews and studies on CUP and related processes in the EU member states, the available information is superficial and limited to selected countries in the EU (2,6,12). Besides, a few gaps exist in the literature, due to changes and revisions of regulations and pathways that happen over time (13). Hence, there is a dearth of information in the published literature on existing CUP and current trends in all EU member states. Therefore, through this literature review we explored the presence of CUP in 28 EU member states to bridge the gaps for a better understanding of the legislation and specifics on CUP in every state.

The objectives of this review are to appraise the existing structure and processes for CUP in 28 EU member states, consolidate the information and present it as a comprehensive overview of the program in the countries.

2. Methodology

Data was collected through an extensive literature review process to present the consolidated information. First, search terms like “compassionate use,” “expanded access,” “patient access programs,” “medicines/drugs regulations,” and “access to new drugs” were defined and included for each member state. Data was extracted using the country-specific search terms from diverse fields of study such as: health policies, medicines for rare diseases, pricing and reimbursement, health care access, health services research, and Federal documents. Iterative database (PubMed MEDLINE) searches were conducted to retrieve articles related to CUP. Since the subject required a thorough and systematic search for literature on regulations and CUP details, the data sources were not limited to articles published in journals, but also included grey literature. The sources for grey literature included: i) Government websites of respective countries; ii) Institutional repositories like the EU Commission, EMA and Rare Diseases Europe (Eurordis); iii) The EUR-Lex for legal documents portraying the medical laws, acts and compassionate use; iv) Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE); v) OpenGrey; vi) Google; and vii) Others (blogs, newsletters and forums).

Additionally, a reference list of relevant articles was reviewed to find other studies. Subsequently, after abstract sifting, relevant articles that described CUP, its regulations and other related information for each member state were retrieved for further study. In instances where the current CUP information in a member state could not be ascertained or was not retrievable through literature search, it was labeled as unavailable. Data were recorded based on a set of three key themes: i) The CUP and a brief overview of the program including its definition in 28 EU member states; ii) National regulations on CUP in each of the 28 EU member states; iii) National authorities responsible for CUP.

For the purpose of this review, the countries under study were stratified into six factions. The EU5 countries are the first faction as they are referred to the most. The rest of the five factions comprise countries classified based on United Nations Geoscheme namely: Western Europe, Eastern Europe, Northern Europe, Southern Europe and Asia. Specific insights from the literature are presented as tables and charts for a meaningful comparison of CUP legislation and processes among the EU member states.

3. Findings

3.1. Early access program

Most of the EU member states have special programs that facilitate early patient access to new medicines through a national authority (14,15). However, the prevailing early access programs are known by various names in each country such as CUP, special access program, Named Patient Program (NPP), managed access program etc. (2,16–20). Moreover, these terms vary based on geographic location and are often used interchangeably. Also, they can imply different ideas with respect to the geographic area (18). Nonetheless, all these programs make a drug available to a patient prior to authorization and commercial launch in the country (2,18).

3.2. Regulations for CUP

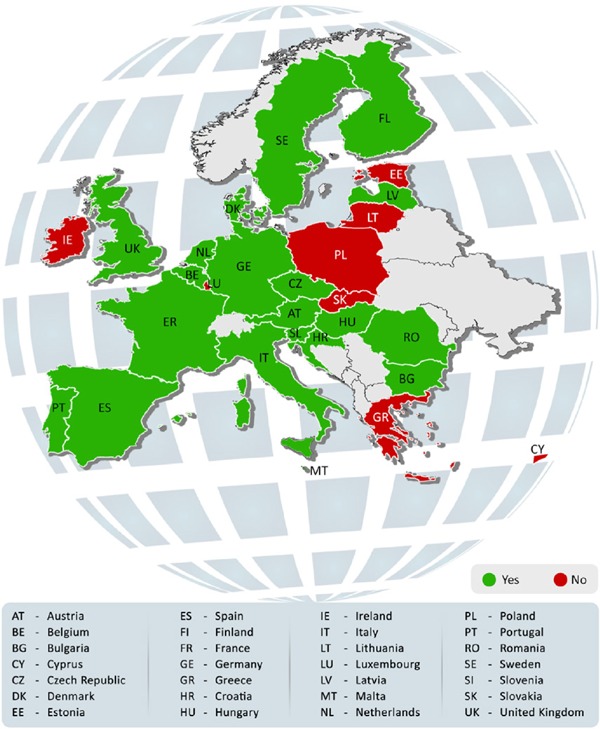

This literature review reports the most recent CUP related processes in the EU member states. The appraisal of available literature such as government websites and reports revealed a strong evidence of adoption of CUP. There was a significantly positive correlation between the EU and individual country laws and recommendations. The results from the reviewed literature on CUP are summarized in Table 2 to Table 7. The tables compile the definition and an overview of CUP along with the medicinal products under it. On the whole, CUP was in place in 20 EU member states (71%) (Figure 2). These countries were Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom (UK). The remaining eight countries (Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland and Slovakia) belonged in one of these categories: i) Did not have a CUP regulation or process; ii) No information was available; iii) Lack of clarity in the retrieved and available information.

Table 2. Compassionate use programs in EU5 countries (Ref. 12,22–38).

| Items | France | Germany | Italy | Spain | UK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authority involved | Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé (ANSM) | German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) and the Paul-Ehrlich Institute (PEI) | Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA) | Spanish Agency of Medicines and Health Products (AEMPS) | Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) |

| Laws and regulations | Article L5121-12 and Article R5121-68 |

|

|

Real Decreto 1015 of 19th June 2009 Cohort or Nominative |

|

| Overview | The conditions for ATU:

Also, there are two types of ATU:

|

Medicinal products for human use can be used for specific groups of patients without marketing authorization or previous approval in Germany | An unauthorized medication can be included by AIFA in the official list to be prescribed at the NHS charge, if it is for a specific disease with no therapeutic choice. Three types of medications that can be included are:

|

|

|

Table 7. Compassionate use program in Asia (Ref. 83).

| Items | Cyprus |

|---|---|

| Authority involved | Pharmaceutical Services of the Ministry of Health |

| Laws and regulations | According to a report published in 2012, there are no regulations in place allowing access to unauthorized medicinal products outside clinical trials |

| Overview | Information unavailable |

Figure 2.

Compassionate use program in the European Union member states. This figure shows the presence of Compassionate use program in various European Union member states. The countries shaded in green have implemented the program and the ones in red have not.

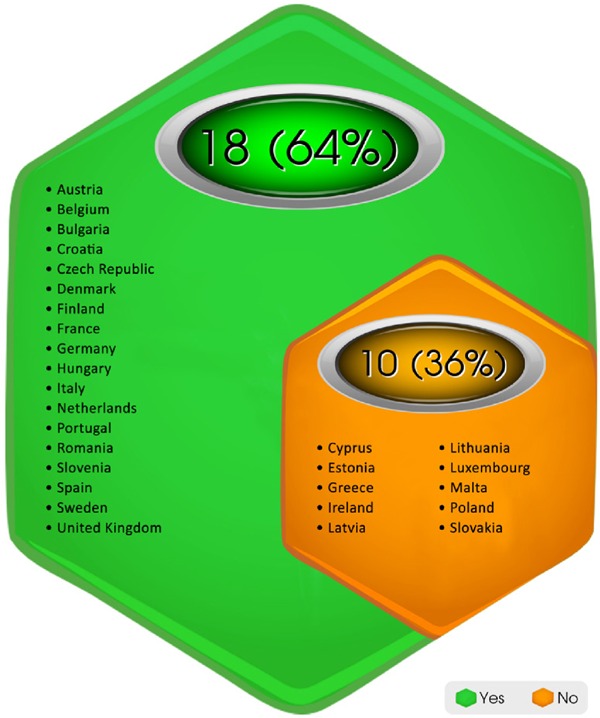

Among the 28 EU member states, 18 (∼64%) had nationalized regulations in place and the processes for CUP were well-defined as per the information gathered (Figure 3). These countries are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom. The decisions were managed and approvals were granted by a competent National Agency in the countries where CUP existed (12).

Figure 3.

Presence of regulations and well-defined processes in the European Union member states. This chart shows that 18 countries of the European Union member states have legislation and a well-defined process in place for Compassionate use program and the rest do not.

According to this review, few countries lack official CUP and regulations. Every EU member state has nationalized regulations based on the EU framework. The national CUP makes medicinal products available either to individuals (NPP) or cohorts of patients governed by every member state's legislation. However, named patient basis is not CUP as per the EU regulations. So, the doctor responsible for the treatment contacts the manufacturer directly (9,19–21). CUP in 28 member states categorized by UN Geoscheme are summarized below.

CUP in EU5: France has an elaborate scheme for CUP called Temporary Authorizations for Use (ATU). It allows the exceptional use of medicinal products without a marketing authorization and not subject to a clinical trial. The program is well-defined with structured regulations and procedures in the rest of EU5 namely Germany, Italy, Spain and UK (Table 2) (12,22–38).

CUP in Western European countries: Among Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg and Netherlands, Luxembourg did not have CUP (Table 3) (12,31,39–46).

Table 3. Compassionate use programs in Western European countries (Ref. 12,31,39–46).

| Items | Austria | Belgium | Luxembourg | Netherlands |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authority involved | Austrian Federal Office for Safety in Health Care (Bundesamt für Sicherheit im Gesundheitswesen, BASG) | Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products (FAMHP) | Direction de la Santé Villa Louvigny Division de la Pharmacie et des Medicaments | Medicines Evaluation Board |

| Laws and regulations | 8a Austrian Medicinal Products Act (AMG) |

|

Regulations specifically for CUP are absent. Further information unavailable | At national level, the legal requirements are implemented in the Medicines Act in Article 40 paragraph 3 (f) and the Ministerial Regulations Article 3.18 |

| Overview | CUP in Austria covers:

|

CUP permits use of medicinal products unauthorized in Belgium, to patients with a chronically or seriously debilitating or life threatening disease, and who cannot be treated satisfactorily by an authorized medicinal product. |

|

If there is no registered alternative available and new drugs for multiple patients (cohort) is deemed necessary before a marketing authorization, a CUP is applicable. NPP also exists. |

CUP in North European countries: In Estonia and Ireland, although there is no CUP, NPP exists. Lithuania does not have the program. Denmark, Finland, Latvia and Sweden do have CUP with Latvia lacking regulations and a clear structure (Table 4) (12,31,47–58).

Table 4. Compassionate use programs in North European countries (Ref. 12,31,47–58).

| Items | Estonia | Denmark | Ireland | Lithuania | Finland | Latvia | Sweden |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authority involved | State Agency of Medicines (SAM) | Lægemiddelstyrelsen-Danish Medicines Agency | Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) | State Medicines Control Agency | Finnish Medicines Agency (Fimea) | State Agency of Medicines of Latvia | Läkemedelsverket/Medical Product Agency (MPA) |

| Laws and regulations | No CUP as in EMEA/27170/2006 but NPP processed by national regulations | Section 29 (1) of the Danish Medicines Act |

|

|

Medicines Decree 693/1987, 1184/2002 and 868/2005 | Regulations for CUP are absent. | §5 of the Medicine Act no 859 of 1992, recently updated the 28th August 2012 Lakemedelsverkets foreskrifter (LVFS) Nominative |

| Overview |

|

Under special conditions, after application, the sale or dispensing of medicinal products in limited amounts (not covered by marketing authorization or not marketed in Denmark) may be authorized | Named patient and clinical trial regimes exist, but not CUP. Further information unavailable. | Information unavailable | Compassionate use is permitted in exceptional cases where no other treatments are appropriate or produce the anticipated effect. Medicines available through CUP are prescription based only. Permission for CUP is needed for:

The permission is valid for one year, starting from the date of issue. |

Compassionate use exists through the Latvian hospitals. However, it is unclear if it is on a named-patient basis or CUP. Further information unavailable. |

An unauthorized medicinal product can be available for compassionate use in Sweden to increase patients' access to drugs being developed in the EU and to enable a common EU procedure. The MPA introduced CUP in 2012 for the Swedish health care as a complement to licensed prescription. |

CUP in Southern European countries: There is minimal information about CUP in Greece and Malta. Though there is a regulatory procedure for CUP in Malta, there is no official legislation. Compassionate use of medicines in individual patients is documented, but there is a dearth of clarity whether this is NPP or CUP. Croatia, Portugal and Slovenia have CUP with national regulations (Table 5) (12,31,59–68).

Table 5. Compassionate use programs in Southern European countries (Ref. 12,31,59–68).

| Items | Croatia | Greece | Malta | Portugal | Slovenia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authority involved | Ministarstvo zdravlja (Ministry of Health) and The Agency for Medicinal Products and Medical Devices of Croatia (HALMED) | National Organization for Medicines | Malta Medicines Authority | Instituto Nacional da Farmacia e do Medicamento (INFARMED) | Javna agencija RS za zdravila in medicinske pripomočke - Public Agency of the Republic of Slovenia for Medicinal Products and Medical Devices (JAZMP) |

| Laws and regulations | Pursuant to Article 73 of the Medicinal Products Act (Official Gazette 71/07 and 45/09) ordinance on pharmacovigilance | Information unavailable (may be in progress) |

|

|

83 Article 6 Medicines Act (Official Gazette of RS, no. 17/14) |

| Overview |

|

|

|

Medicines, including the ones for compassionate use without a marketing authorization, under special and exceptional circumstances, can be used to treat patients in always under an authorization granted with a temporary and transitory nature by the INFARMED | In Slovenia, in line with the EU regulation, CUP is:

|

CUP Eastern European countries: Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania have CUP with legislation in place. There is no CUP in Poland. In Slovakia, there is no CUP, but participation of patients in international registries influences CUP (Table 6) (12,31,69–82).

Table 6. Compassionate use programs Eastern European countries (Ref. 12,31,69–82).

| Items | Czech Republic | Bulgaria | Hungary | Poland | Romania | Slovakia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authority involved | State Institute for Drug Control (SÚKL) | Ministry of Health | Országos Gyógyszerészeti és Élelmezés-egészségügyi (OGYÉI) Intézet National Institute of Pharmacy and Nutrition | Office for Registration of Medicinal Products, Medical Devices and Biocidal Products | National Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices (NAMMD) | State Institute for Drug Control |

| Laws and regulations | Act on Pharmaceuticals No. 378/2007

|

Regulation N° 10/17 November 2011 | Act XCV of 2005 on Medicinal Products for Human Use and on the Amendment of Other Regulations Related to Medicinal Products Section 25/C (effective since January 2016) | No CUP. Further information unavailable. |

Ministry of Health, Order no. 1018 of 3 September 2014 on approval of Conditions for authorization of human medicinal products for compassionate use, in accordance with provisions of Article 83 of Regulation (EC) no. 726/2004 of EU | Information unavailable |

| Overview |

|

Medicinal products for human use without marketing authorization in Bulgaria are accessible through CUP. However, the current regulation concerns only medicines approved by the EMA | CUP is available for life-threatening or debilitating medical condition. The manufacturer is to provide the drug free for CUP. Further information unavailable. |

|

The medicinal products possibly accessible with CUP are:

|

Participation of the patients in Slovakia in the international registries influences CUP. Implementation and streamlining CUP is in progress. No further information available. |

CUP in Asia: There are no regulations allowing access to unauthorized medicinal products outside clinical trials in Cyprus (Table 7) (83).

3.3. Recent changes

The literature review deduces that countries like Hungary and Sweden, without national legislation previously, have now formulated them (13). Newly shaped policies and regulations have resulted due to higher demand for CUP, especially for orphan drugs for rare diseases. Clear regulations aid in systematizing CUP and providing better access to medicines. For instance, more than 20,000 patients were treated with over 200 products under French legislation for compassionate use by 2007 (84). A study on all ATUs with marketing authorization between 01 January, 2005, and 30 June, 2010, concluded that the licensing and public bodies' review time was shortened by a combined total of 36 months. Also, the French ATU program accelerated the availability of new drugs in spite of the longer standard administrative path (85). Since 2006, the EU member states submitted more than 50 CUP notifications to the EMA, of which around two-fifths were for orphan medicinal products (6).

3.4. Benefits of CUP

Implementing early access programs like CUP has multifold benefits, both to patients and pharmaceutical companies (18,86–92). First, CUPs benefit patients unable to participate in clinical trials due to mobility issues or who fail to fulfill the eligibility criteria (13). They are also preferred when no treatment options are available or access to investigational drug/biologics/medical devices is the last resort for patients suffering from serious diseases/disorders (13). Through early access programs, patients have access to promising drugs at an earlier stage during the life cycle, for instance, post phase II. Otherwise, patients have to wait for a considerable amount of time until the drug is authorized and is on the market, if not for the early access programs (13). Second, pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies provide a fast and efficient response to patient demand outside of traditional access routes due to such programs (87,90). Early access facilitates the smoother transition of a drug from clinical trials to the market and also prepares companies to develop global launch strategies based on global usage patterns and market landscape predictions (86,88,89). Besides, the market authorization holders get the opportunity to resolve any product related issues and can overcome challenges encountered by pre-approved drugs through early access (19,88). Above all, early access furnishes valuable information pertaining to real world evidence for practice and further research (18,20). Furthermore, patients, physicians and patient organizations are increasingly becoming aware of the possibilities to access a drug through such early access programs. Moreover, the existing framework for compassionate use in the EU member states can be effectively utilized to plan new access programs. For instance, the adaptive pathways approach, a scientific concept for medicine development and data generation, is part of the EMA's efforts to improve timely access for patients to new medicines that utilize the existing EU regulatory framework for medicines (93,94).

3.5. Challenges in implementing CUP

The governments and pharmaceutical companies are taking steps to implement CUP considering the benefits and importance of early access to drugs. However, it is highly challenging and complex for pharmaceutical companies to initiate early access programs like CUP. First, despite the existing EU Regulations, pharmaceutical companies face challenges as the regulations vary from country to country. This mandates regulators, policy makers and other key stakeholders to streamline processes and create transparency. Second, innovative drugs are relatively expensive and are becoming increasingly difficult for governments and payers to include them in their reimbursement schemes. This mandates for clearly set regulations and rationalized procedures to help patients, patient organizations and physicians for better access to drugs. Additionally, it is imperative for pharmaceutical companies to be updated on these regulations and processes on CUP for easier entrance into a market.

3.6. Strengths and limitations of this study

This review has its own strengths and limitations. Previously, the information available publicly on CUP, especially on legislation was limited and in many cases outdated when compared with the available grey literature (6,12,13). However, the current systematic search addresses these gaps by including data from grey literature and peer-reviewed journal articles. Despite the efforts by researchers to capture all the available data, there still exist a few gaps in the literature. For instance, information on CUP is not available online for certain member states where CUP is still in the initial stages.

4. Conclusion and recommendations

Overall, this review identified the presence of CUP and highlighted its current status and legislation in 28 EU member states. This review found that CUP has a positive impact and potential benefits for patients and pharmaceutical companies. The established legislation for CUP in the EU member states suggests that the EU countries are ready to adopt methods for early access to medicines. An implication of this is the possibility to make new medicines available within a shorter time span for patients. Furthermore, the existing framework for compassionate use in the EU member states can pave the way for more access programs.

Further research is necessary to determine the specific phases involved in the CUP, pricing and reimbursement frameworks in countries. Case studies and success stories which reflect the benefits of such early access programs from both patients' and other stakeholders' perspectives can give the relevant impetus for education on such programs. Since inadequate information on healthcare access can often be a stumbling block for stakeholders, periodic reviews need to be taken to throw light on emerging changes within the regulatory structures, both at European and member state levels to discern market trends.

References

- 1. Rahbari M, Rahbari NN. Compassionate use of medicinal products in Europe: Current status and perspectives. Bull World Health Organ. 2011; 89:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patil S. Early access programs: Benefits, challenges, and key considerations for successful implementation. Perspect Clin Res. 2016; 7:4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Global Genes. RARE Diseases: Facts and Statistics. https://globalgenes.org/rare-diseases-facts-statistics/ (accessed June 16, 2016).

- 4. Howes M. Compassionate use and the impact on clinical research. http://www.centerwatch.com/news-online/2016/04/11/compassionate-use-impact-clinical-research/ (accessed June 16, 2016).

- 5. Shire. Shire's Position on Offering Compassionate Use to Investigational Medicines. https://www.shire.com/who-we-are/how-we-operate/policies-and-positions/compassionate-use (accessed August 11, 2016).

- 6. Hyry HI, Manuel J, Cox TM, Roos JC. Compassionate use of orphan drugs. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015; 10:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elstein D, Zimran A. Review of the safety and efficacy of imiglucerase treatment of Gaucher disease. Biologics. 2009; 3:407-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. European Medicines Agency. Compassionate use. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000293.jsp (accessed August 11, 2016).

- 9. European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Compassionate Use of Medicinal Products, Pursuant to Article 83 of Regulation (Ec) No 726/2004 European Medicines Agency. London, UK, 2007; pp. 1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 10. European Medicines Agency. Regulation (Ec) No 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004. Agency EM, ed. European Medicines Agency, 2004; pp. 1-70. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benisheva-Dimitrova DT. Challenges for the Pharmaceutical Legislative Implementation in Terms of an Accelerated Market Access After October 2005 University of Bonn, Bonn, 2006; pp. 1-68. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Urbinati D, Masetti L, Toumi M. Early Access Programmes (EAPs): Review of European system. In: ISPOR 15th Annual European Congress (ISPOR, Berlin, 2012; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Whitfield K, Huemer KH, Winter D, et al. Compassionate use of interventions: Results of a European Clinical Research Infrastructures Network (ECRIN) survey of ten European countries. Trials. 2010; 11:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. EUCERD. Links to national authorities websites. http://www.eurordis.org/content/links-national-authorities-websites (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 15. European Commission. Inventory of Union and Member State incentives to support research into, and the development and availability of, orphan medicinal products State of Play 2015. 2015; pp. 1-36. [Google Scholar]

- 16. FDA. Expanded Access (Compassionate Use). http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/ExpandedAccessCompassionateUse/default.htm#main (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 17. U.S National Library of Medicine. FAQ: ClinicalTrials. govt - What is “Expanded Access”? https://www.nlm.nih. gov/services/ctexpaccess.html (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 18. BioIndustry Association and Clinigen Group. Early access in practice BioIndustry Association and Clinigen Group, 2014; pp. 1-6. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pharmalinx LLC P. Named Patient Programs. http://www.idispharma.com/sites/default/files/uploads/pharmavoice_epicept_may2010.pdf (accessed June 14, 2016).

- 20. Ceepharma. CEE countries give chance to drug pre-launch within Named Patient Programmes - Pharma & healthcare market in CEE & CIS - PMR http://www.ceepharma.com/news/103152/cee-countries-give-chance-to-drug-pre-launch-within-named-patient-programmes (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 21. European Medical Agency. Questions and answers on the compassionate use of medicines in the European Union European Medical Agency, 2010; pp. 1-3. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé. Autorisations temporaires d'utilisation (ATU). http://ansm.sante.fr/Activites/Autorisations-temporaires-d-utilisation-ATU/ATU-Reglementation/(offset)/8 (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 23. Bélorgey C. Temporary Authorisations for Use (ATU). http://agence-tst.ansm.sante.fr/html/pdf/5/atu_eng.pdf (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 24. Code de la Santé Publique. Legifrance: Article L5121-12. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichCodeArticle.do?cidTexte=LEGITEXT000006072665&idArticle=LEGIARTI0 00006689900&dateTexte=&categorieLien=cid (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 25. Autorisation de mise sur le marché - Ministère des Affaires sociales et de la Santé. Temporary use authorizations (ATU). http://social-sante.gouv.fr/soins-et-maladies/medicaments/professionnels-de-sante/autorisation-de-mise-sur-le-marche/article/autorisations-temporaires-d-utilisation-atu (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 26. BfArM. “Compassionate use” programs http://www.bfarm.de/EN/Drugs/licensing/clinicalTrials/compUse/_node.html (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 27. Agenzia Farmaco. Decreti, Delibere e Ordinanze Ministeriali. Agenzia Farmaco, 2003; pp. 1-2. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Agenzia Farmaco. Collection of national regulations about clinical trials with medicines. https://www.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/ricclin/it/node/3 (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 29. Aymé S, Rodwell C, eds. 2012 Report on the State of the Art oF Rare Disease Activities in Europe of the European Union Committee of Experts on Rare Diseases - Italy. EUCERD, 2012; pp. 1-20. [Google Scholar]

- 30. EURORDIS. Europlan - National Conferences Final Report of the Conference in Italy 2010; pp. 1-24. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Conference Bleue. Pricing and Reimbursement Questions. http://www.arthurcox.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Pricing-and-Reimbursement-Questions.pdf (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 32. Hernández García C. Spanish routes for making available medicines to patients before authorisation. Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS); ; pp. 1-17. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Instrucciones para la tramitación de solicitudes. http://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentosUsoHumano/medSituacionesEspeciales/instruccTramitacion.htm (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 34. State Agency. Boletín Oficial del Estado. 2009. http://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2009/07/20/pdfs/BOE-A-2009–12002.pdf (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 35. O'Connor D. Early Access to Medicines Scheme (EAMS). 2015; pp. 1-13. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Government of UK. The Human Medicines Regulations 2012 The Stationery Office, 2012; pp. 1-322. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Apply for the early access to medicines scheme (EAMS). https://www.gov.uk/guidance/apply-for-the-early-access-to-medicines-scheme-eams (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 38. Government of UK. The supply of unlicensed medicinal products (“specials”). Norwich, 2014. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/1916/pdfs/uksi_20121916_en.pdf (accessed August 12, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Austrian Federal Office for Safety in Health Care - BASG. Overview Compassionate Use Programs in Austria (AT). 2014. http://www.basg.gv.at/fileadmin/redakteure/F_I453_Liste_CUP_in_AT_010.pdf (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 40. Austrian Federal Office for Safety in Health Care - BASG. Compassionate Use Programs in Austria. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Musch G. Unmet medical need strategy of FAMHP, moving to more adaptive pathways 2015; pp. 1-20. [Google Scholar]

- 42. FAMHP. 25 April 2014 - Royal Decree amending the Royal Decree of 14 December 2006 on human and veterinary medicines. Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products. http://www.fagg-afmps.be/en/human_use/medicines/medicines/research_development/compassionate_use_medical_need (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 43. FAMHP. Compassionate use - medical need www.fagg-afmps.be/en/human_use/medicines/medicines/research_development/compassionate_use_medical_need (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 44. Division de la Pharmacie et des Médicaments -Luxembourg. Division of Pharmacy and Medicines. www.sante.public.lu/fr/politique-sante/ministere-sante/direction-sante/div-pharmacie-medicaments/index.html (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 45. Geneesmiddelen CBG. Compassionate use programma. http://www.cbg-meb.nl/voor-mensen/voor-handelsvergunninghouders/inhoud/voor-aanvraag-handelsvergunning/compassionate-use-programma (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 46. Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg. Medicines without marketing authorization. http://www.igz.nl/english/medicines/medicines_without_marketing_authorization/ (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 47. Ravimiamet. The compassionate use programs under Estonian legislation http://www.ravimiamet.ee/en/compassionate-use-programs-under-estonian-legislation (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 48. Danish Health and Medicines Authority. Danish Medicines Act Ministry of the Interior and Health. Danish Medicines Act Ministry of the Interior and Health, 2016; pp. 1-34. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kavanagh C, Diamond D, O'Gorman M. http://www.arthurcox.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/European- Lawyer-Reference-2013-Guide-to-the-Distribution-and- Marketing-of-Drugs8478574_1.pdf. 2013 (accessed August 12, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 50. HPRA. Access to Medicines Prior to Authorisation. www.hpra.ie/homepage/medicines/regulatory-information/medicines-authorisation/access-to-medicines-prior-to-authorisation (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 51. Lessem E. An Activist's Guide to Regulatory Issues: Ensuring Fair Evaluation of and Access to Tuberculosis Treatment. TAG - Treatment Action Group, 2015; pp. 1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fimea. Special permission for compassionate use. http://www.fimea.fi/web/en/pharmaceutical_safety_and_information/special_permission_for_compassionate_use (accessed August 12, 2016).

- 53. Fimea. Special licence procedure in Finland. Finnish Medicines Agency - Fimea, 2014; pp. 1-3. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Logviss K, Krievins D, Purvina S. Rare diseases and orphan drugs: Latvian story. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014; 9:147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. State Agency of Medicines of the Republic of Latvia. Cabinet of Ministers Regulation No. 47, Procedure for Pharmacovigilance. https://www.zva.gov.lv/index.php?id=633&lang=&top=333&sa=380 (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 56. Läkemedelsverket/Medical Products Agency. Applications for medicinal products are made available for compassionate use (compassionate use program, CUP). https://lakemedelsverket.se/malgrupp/Foretag/Lakemedel/Compassionate-Use-Program/ (accessed August 16, 2016).

- 57. Riksdagen. Parliment S. Drugs Act (1992: 859). http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lakemedelslag-1992859_sfs-1992–859 (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 58. Läkemedelsverkets författningssamling. Läkemedelsverkets författningssamling. Agency L-MP, ed. Läkemedelsverkets - Medical Products Agency, 2012; pp. 1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 59. The Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Ordinance on Pharmacovigilance Welfare TMoHaS, ed. The Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, 2009; pp. 1-88. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rodwell C, Aymé S. eds., 2014 Report on the State of the Art of Rare Disease Activities in Europe - Croatia. EUCERD, 2014; pp. 1-11. [Google Scholar]

- 61. EUCERD. Greece Europlan national conference final report EUCERD, Athens: 2012; pp. 1-33. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Eof. Information of Organization. http://www.eof.gr/web/guest (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 63. Medicines Working Group. Medicines with Special Legal Status. 2012. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&cad=rja&uact=8&ved= 0ahUKEwi09L3r6szMAhXHRI4KHX7dDHQQFgguMAM&url=https%3A%2F%2Fhealth.gov.mt%2Fen%2Fsph%2FDocuments%2Fannex1_nsum.doc&usg=AFQjCNF6D CTqdoCgZ6GIXUzYYzOzJioDnQ&bvm=bv.121421273,d.c2E (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 64. Busuttil R. Guidelines for the supply of medicinal products for human use through processes which are not covered by the Medicines Act, 2003 and its subsidiary legislation (unlicensed medicinal products) - DH Circular 270/06 2006; pp. 1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rodwell C, Aymé S. 2014 report on the state of the art of rare disease activities in EUROPE - Malta. European Comission, 2014; pp. 1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Leitão M, Teles G, Soares da Silva Associates Law Firm, R.L. Matoso F, Maia Cadete E. European lawyer reference series - Portugal. 2013; pp. 1-17. [Google Scholar]

- 67. EUCERD. Europlan national conference final report - Portugal Lisbon, 2016; pp. 1-58. [Google Scholar]

- 68. PISRS. Medicines Act (ZZdr-2). http://pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO6295 (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 69. State Institute for Drug Control. Act of 6 December 2007 on Pharmaceuticals and on Amendments to Some Related Acts (the Act on Pharmaceuticals) 2007. http://www.sukl.eu/uploads/Legislativa/Zakon_o_lecivech_EN_corr_clean2.pdf (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 70. State Institute for Drug Control. Use of non-authorized medicinal products. 2016. http://www.sukl.eu/medicines/use-of-non-authorised-medicinal-products?highlightWord s=compassionate+use (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 71. Rodwell C, Aymé S, eds. 2014 Report on the State of the Art of Rare Disease Activities in Europe - Bulgaria. 2014; pp. 1-16. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hasardzhiev S. Bulgarian national hepatitis plan and compassionate use regulations. http://www.elpa-info.org/elpa-news---reader/items/compassionate-use-in-hepatitis-c-saving-lives-of-patients-who-cannot-wait.htm?file=tl_files/elpa_downloads/2013%20content/ELPA%20Symposium%202013/Stanimir%20Hasardzhiev%20-%20Bulgarian%20national%20hepatitis%20plan%20anc%20 compassionate%20use%20regulations.ppt. Presentation presented at; 2016; Bulgaria (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 73. EUCERD. Europlan national conference final report - Hungary. Budapest, 2013; pp. 1-36. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lexology. European - pharmaceutical & healthcare newsletter. http://www.lexology.com/library/detail. aspx?g=d839298b-757c-4531–8b1d-4774fedd6472 (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 75. Jogtar. Act XCV of 2005 on Medicinal Products for Human Use and on the Amendment of Other Regulations Related to Medicinal Products. http://net.jogtar.hu/jr/gen/getdoc.cgi?docid=a0500095.tv&dbnum=62#lbj203id8e8 (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 76. Országos Gyógyszerészeti és Élelmezés-egészségügyi. Laws. http://www.ogyei.gov.hu/laws_and_regulations/ (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 77. Aymé S, Rodwell C, eds. 2012 Report on the state of the art of rare disease activities in Europe of the European union committee of experts on rare diseases - Poland 2012; pp. 1-13. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zakrzewski Palinka Sp. k D MM, Kaczyński T, Najbuk P. European lawyer reference series - Poland. 2016; pp. 1-16. [Google Scholar]

- 79. EUCERD. Europlan national conference final report - Romania Bucharest, 2013; pp. 1-36. [Google Scholar]

- 80. National Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices. Romania Newsletter - National Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices. National Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices, 2014. http://www.anm.ro/anmdm/en/_/INFORMATIVE%20BULLETIN/IB%203_2014.pdf (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 81. EUCERD. Slovakia europlan national conference final report EUCERD, Bratislava, 2013; pp. 1-46.

- 82. Partners Ca. Financial law news Cechova.sk, Bratislava, 2005; pp. 1-11. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Aymé S, Rodwell C, eds. 2013 Report on the state of the art of rare disease activities in Europe - Cyprus EUCERD, 2013; pp. 1-11. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jones Day. Compassionate Use in Europe: A Patchy Framework for Early Market Entry. http://www.jonesday. com/compassionate-use-in-europe-a-patchy-frame-work-for-early-market-entry-08–20–2010/ (accessed August 19, 2016).

- 85. Degrassat-Theas A, Paubel P, Parent de Curzon O, Le Pen C, Sinegre M. Temporary authorization for use: Does the French patient access programme for unlicensed medicines impact market access after formal licensing? Pharmacoeconomics. 2013; 31:335-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. PAREXEL. Managed Access Programs PAREXEL, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bates A. Evidence of increased market share. Journal of Medical Marketing. 2008; 8:319-324. [Google Scholar]

- 88. PAREXEL. Expanded Access Programs https://www.parexel.com/solutions/access/late-stage-clinical-operations/expanded-access-programs (accessed August 22, 2016).

- 89. McKinsey & Company. The secret of successful drug launches http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/pharmaceuticals-and-medical-products/our-insights/the-secret-of-successful-drug-launches (accessed August 22, 2016).

- 90. Merck. Access to Investigational Medicines http://www.merck.com/about/views-and-positions/access-to-medicines/home.html (accessed August 22, 2016).

- 91. Darrow JJ, Sarpatwari A, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. Practical, legal, and ethical issues in expanded access to investigational drugs. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:279-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Plate V. The Impact of Off-Label, Compassionate and Unlicensed Use on Health Care Laws in preselected Countries. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Regulatory Affairs, Bonn, 2009; pp. 1-174. [Google Scholar]

- 93. European Medicines Agency. Human regulatory - Adaptive pathways http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000601.jsp (accessed August 22, 2016).

- 94. European Medicines Agency. Human Regulatory - Adaptive Pathways http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000601.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05807d58ce (accessed August 22, 2016).