SUMMARY

Bacillus subtilis is one of the best-studied organisms. Due to the broad knowledge and annotation and the well-developed genetic system, this bacterium is an excellent starting point for genome minimization with the aim of constructing a minimal cell. We have analyzed the genome of B. subtilis and selected all genes that are required to allow life in complex medium at 37°C. This selection is based on the known information on essential genes and functions as well as on gene and protein expression data and gene conservation. The list presented here includes 523 and 119 genes coding for proteins and RNAs, respectively. These proteins and RNAs are required for the basic functions of life in information processing (replication and chromosome maintenance, transcription, translation, protein folding, and secretion), metabolism, cell division, and the integrity of the minimal cell. The completeness of the selected metabolic pathways, reactions, and enzymes was verified by the development of a model of metabolism of the minimal cell. A comparison of the MiniBacillus genome to the recently reported designed minimal genome of Mycoplasma mycoides JCVI-syn3.0 indicates excellent agreement in the information-processing pathways, whereas each species has a metabolism that reflects specific evolution and adaptation. The blueprint of MiniBacillus presented here serves as the starting point for a successive reduction of the B. subtilis genome.

INTRODUCTION

Three technological revolutions dramatically changed our view of biology. The genomic revolution gives us access to genome sequences of any organism of interest at low cost. The analytical revolution, especially with respect to mass spectrometry, allows us not only to detect the presence and the fluxes of any molecule in the cell but also to study its precise concentration under any desired condition. Last but not least, the informatics revolution paves the way for the evaluation of the tremendous data sets and for the generation of meaningful models and predictions of cellular behavior. However, even knowledge of all components of a cell and of their precise concentrations does not give us a complete understanding of a living cell. For this, we have to consider all the functional interactions between different biological molecules and the dynamics of both the molecules and their interactions.

The complexity of all naturally existing organisms still precludes a deep understanding of the functions of all components of a cell and their interactions. Even small organisms such as bacteria are too complex to understand all processes in their cells. This is even the case for bacteria with naturally minimal genomes, as found in the genus Mycoplasma. These bacteria may have as few as 482 protein-coding genes and are still capable of independent life in the absence of any host cells. However, the functions of many Mycoplasma genes are so far unknown, and not the full gene set is essential, indicating that we are far from a full picture of these bacteria despite tremendous efforts in their analysis (1–8).

These limitations in our understanding of natural organisms call for a reduction of complexity: the creation of cells with a defined set of genes. Such cells can be obtained by applying either bottom-up or top-down approaches. The former approach has so far been pursued with the chemical synthesis of a bacterial genome and its application to create a semiartificial cell (9, 10). In this case, a known genome was reduced and transplanted into a closely related host cell. With only 473 protein-coding genes, the recently achieved Mycoplasma mycoides JCVI-syn3.0 minigenome is so far the smallest semiartificially designed organism. Importantly, about one-third of the proteins in this minimal cell are of unknown function (10). Moreover, there have been attempts to create so-called protocells, which are lipid vesicles that contain genetic material and/or enzymes (11–14). Even though protocells do not allow recapitulation of the evolutionary emergence of life, they are well-suited systems to study the physical and biochemical properties of basic cellular processes such as self-reproduction, permeability, enzymatic replication, and Darwinian evolution (15–17). Reduction of complexity can also be achieved by a top-down approach that starts with existing bacteria and aims at consecutively reducing their complexity. This approach is, of course, very time-consuming; on the other hand, it allows advancing from step to step. Moreover, this iterative process of genome reduction allows the immediate discovery of possible problems and, thus, finding appropriate solutions. Genome reduction is a common theme in synthetic biology, not only for pure scientific curiosity but also from an industrial point of view to create workhorses for biotechnology. Ongoing projects of genome reduction have been reported for several intensively studied bacteria such as Bacillus subtilis, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas putida, and Streptomyces avermitilis (18–27; for a review, see reference 28) as well as for yeast (29). All these projects are still far from the final goal, the minimal cell.

With the progress of genome reduction, it is necessary to define the set of genes that should be part of the final minimal genome. It is obvious that such a set of genes is determined by several factors, including the intended lifestyle of the final minimal cell, but also by the general biology of the organism that is to be reduced. Conceivably, a eukaryotic yeast cell will still contain a nucleus even at a late genome reduction stage. Similarly, the bacteria mentioned above differ strongly in their cellular organizations. For example, M. mycoides does not possess a cell wall, while the cell wall is differently structured yet essential in B. subtilis, C. glutamicum, and E. coli. In this work, we aim at defining the set of genes that is required for the life of a minimal cell based on B. subtilis. For several reasons, this bacterium is particularly well suited for genome minimization approaches. First, B. subtilis is one of the most intensively studied organisms, with extensive genome annotation and excellent knowledge of the major cellular processes. Second, the elaborated genetic system for B. subtilis makes all kinds of genetic manipulations very easy (see below). Finally, B. subtilis is one of the major organisms in biotechnology, suggesting that genome-reduced strains may also serve as a chassis for novel applications.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR THE DEFINITION OF THE GENE SET FOR A MINIMAL CELL

Several independent sets of information serve as the basis to define which genes are required for a viable minimal cell. First of all, this is the set of essential genes. These genes were identified for B. subtilis in 2003 (30). In addition, large dispensable regions of the chromosome have been studied, resulting in the identification of novel essential and coessential genes (31). A recent reevaluation of the essential genes of B. subtilis revealed that several metabolic genes involved in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle originally listed as essential could be removed from the list. With the exception of the ylaN gene, all other genes of unknown function could also be removed from the list (32, 33). Moreover, recent studies indicated that the ycgG and yfkN genes as well as the rny gene, encoding RNase Y, are also dispensable (28, 34; our unpublished data). The current list of 251 essential protein-coding genes is available in the SubtiWiki database (http://subtiwiki.uni-goettingen.de/wiki/index.php/Essential_genes) (33).

The essential genes are by definition only those genes that cannot be deleted as single genes under defined optimal growth conditions (for B. subtilis, lysogeny broth [LB] with glucose at 37°C). Moreover, a recent knockdown study of essential B. subtilis genes showed that the encoded proteins are also very important for outgrowth from stationary phase, adding another level of relevance (35). However, many genes are redundant, and cellular functions can be achieved in completely different ways. The former is the case for DNA polymerase I (PolA) and its paralog YpcP or the diadenylate cyclase CdaA and one of the paralogs DisA and CdaS (36, 37). Moreover, the same function may even be fulfilled by unrelated proteins, as observed for the membrane anchors for the Z-ring protein for cell division, FtsZ. In E. coli, the essential FtsA protein serves as a membrane anchor for FtsZ. Why FtsA is nonessential in B. subtilis has been enigmatic for a long time. Only the discovery of the unrelated alternative membrane anchor SepF provided the answer (38). Finally, alternative pathways may lead to the same results. This is obvious in the acquisition of cellular building blocks such as amino acids and nucleotides. These metabolites can be either synthesized in the cell or taken up from the medium. In any case, none of the involved genes would be classified as being essential. In all these cases, a decision has to be made regarding which of the possible alternatives will be included in the minimal gene set. Accordingly, the gene complement of a minimal organism has to be designed according to essential functions.

If B. subtilis possesses multiple genes for the same function, one of them has to be selected. The criteria for the selection applied in this study are as follows. (i) The final number of genes should be as small as possible. Therefore, it seems reasonable to include transporters rather than biosynthetic genes for the acquisition of building blocks whenever possible. (ii) In some functional categories, such as cell division, the deletion of a gene may have only a mild effect; however, combination with the deletion of a second, sometimes functionally unrelated gene may be lethal (see “Cell Division,” below, for details). Therefore, such synthetic lethalities have to be considered. (iii) Prior decisions will have an impact on later selections. This is the case, for example, for cell wall-biosynthetic proteins (see below). (iv) Both gene expression and protein levels have been extensively studied in B. subtilis, and all these data are accessible in the SubtiWiki database (33, 39–41). In case of doubt, the most strongly expressed protein has been chosen. (v) Finally, conservation of genes served as a criterion. More strongly conserved genes were preferred over less conserved genes. In this respect, gene conservation and essentiality in genome-reduced Mycoplasma and other mollicutes species and the inclusion of genes in the genome of M. mycoides JCVI-syn3.0 had a high priority (8, 10, 42).

In many cases, it is not known whether a gene is truly required in the context of a minimal cell. In particular, this is the case for functions involved in RNA modification. In these cases, expression levels and gene conservation were valuable clues for deciding whether a gene should be included in the minimal gene list or not. Based on the list of the most abundant proteins (see http://subtiwiki.uni-goettingen.de/wiki/index.php/Most_abundant_proteins) (33, 43), we have decided whether there is a good reason to keep the corresponding genes or not. As an example, highly abundant enzymes required for amino acid biosynthesis were selected for deletion, whereas RNA chaperones were added. Similarly, genes conserved both in all mollicutes and in B. subtilis were regarded as being highly relevant for a minimal organism based on B. subtilis.

THE GENETIC COMPLEMENT OF A MINIMAL CELL

Based on the considerations explained above, we have selected 523 and 119 protein- and RNA-coding genes, respectively, as being important for a minimal organism that is capable of growing in LB medium supplemented with glucose at 37°C. Moreover, the growth and physiology of the minimal cell should be comparable to those of B. subtilis wild-type cells. B. subtilis has a generation time of about 20 min, whereas natural minimal organisms like M. mycoides and Mycoplasma pneumoniae divide in about 1 and 30 h, respectively. The minimal organism M. mycoides JCVI-syn3.0 has a generation time of 180 min (10, 44). This slow growth of Mycoplasma cells is another reason to rely on B. subtilis as the basis for a minimal cell. Most likely, a reduction of the growth rate has to be expected; however, the set of genes suggested in this study should allow generation times of <1 h. As a consequence, the number of genes included in the list is much larger than that of essential genes in B. subtilis 168. Moreover, not all essential genes are required for a minimal cell since several essential genes fulfill protective functions that are dispensable if, e.g., prophages have been deleted (32).

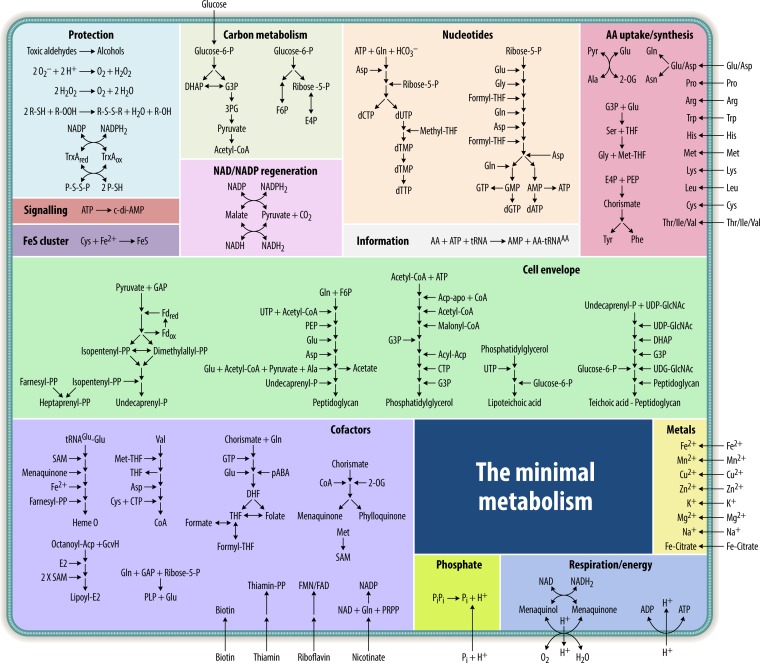

The genes of this minimal set satisfy all essential functions of the cell, such as information processing (DNA replication, transcription, and translation), metabolic pathways (metabolism of building blocks and cofactors and acquisition of ions, etc.), as well as cell division and integrity. Interestingly, there is a very good match between the genes in the MiniBacillus minimal gene set and those of M. mycoides JCVI-syn3.0 as far as information processing is concerned. In contrast, the two lists show only little overlap of genes required for metabolism, cell division, and protective functions. An overview of the set of genes required for MiniBacillus is provided in Table 1. A model of the metabolism of the minimal cell is outlined in Fig. 1, and details that include all metabolic pathways, reactions, and enzymes are provided in Fig. 2 to 11. Detailed information on each individual gene can be found in Tables 2 and 3 and Table S1 in the supplemental material. Table 2 also shows whether the components proposed to be important in the frame of a minimal B. subtilis genome are also present in the recently published minimal strain M. mycoides JCVI-syn3.0.

TABLE 1.

Overview of the genetic complement of a minimal B. subtilis cell

| Function | No. of proteins (no. of essential proteins)a | No. of RNA genes (no. of essential genes)a | Figure(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information processing | 197 (125) | 119 (2) | |

| DNA replication | 18 (15) | ||

| Chromosome maintenance | 13 (9) | ||

| Transcription | 8 (5) | ||

| RNA folding and degradation | 6 (1) | ||

| Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases | 24 (23) | 4 | |

| Ribosomal proteins | 53 (35) | ||

| rRNA and tRNA | 116 (0) | ||

| rRNA/tRNA maturation and modification | 31 (13) | 1 (1) | |

| Ribosome maturation and assembly | 9 (6) | ||

| Translation factors | 11 (9) | ||

| Translation/other | 5 (2) | 1 (0) | |

| Protein secretion | 12 (5) | 1 (1) | 2 |

| Proteolysis, protein quality control, chaperones | 7 (2) | ||

| Metabolism | 218 (59) | ||

| Central carbon metabolism | 26 (4) | 3 | |

| Respiration/energy | 16 (2) | 3 | |

| Amino acids | 30 (1)b | 3 | |

| Nucleotides/phosphate | 36 (11) | 2, 5 | |

| Lipids | 19 (17) | 6 | |

| Cofactors | 62 (14)b | ||

| General components of ECF transporters | 3 (0)b | 4, 7 | |

| NAD | 5 (4) | 7 | |

| FAD | 2 (1)b | 7 | |

| Pyridoxal phosphate | 2 (0) | 7 | |

| Biotin | 1 (0)b | 7 | |

| Thiamine | 2 (0)b | 7 | |

| Lipoate | 4 (1) | 7 | |

| Coenzyme A | 9 (1) | 7 | |

| S-Adenosylmethionine | 1 (1) | 7 | |

| Folate | 13 (1) | 8 | |

| Heme | 12 (0) | 8 | |

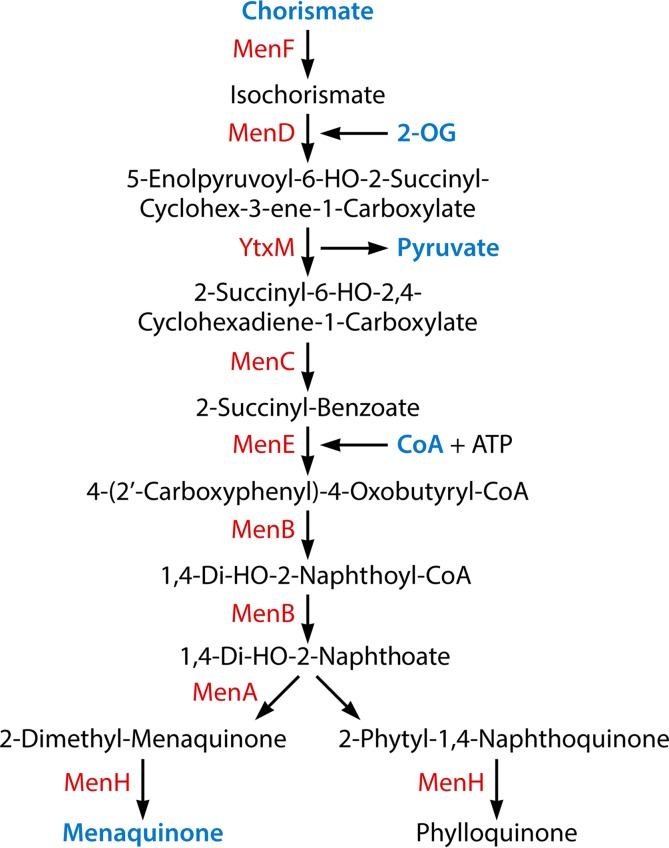

| Menaquinone | 8 (5) | 9 | |

| Metals/iron-sulfur clusters | 29 (10) | 2, 7 | |

| Cell division | 81 (52) | ||

| Cell wall synthesis | 55 (41) | ||

| Amino acid precursor | 11 (10) | 10 | |

| Undecaprenyl phosphate | 13 (10) | 10 | |

| Lipid II biosynthesis | 12 (11) | 10 | |

| Peptidoglycan polymerization | 5 (1) | 10 | |

| Wall teichoic acid | 9 (8) | 11 | |

| Lipoteichoic acid | 5 (1) | 6 | |

| Coordination | 22 (9) | ||

| Signaling | 4 (2) | 2 | |

| Integrity of the cell | 16 (5) | ||

| Protection | 8 (4) | 2 | |

| Repair/genome integrity | 8 (1) | ||

| Other/unknown | 11 (2) | ||

| Total minimal genome | 523 (243) | 119 (2) |

The numbers of proteins and RNAs required for each function are listed. Numbers in parentheses indicate the numbers of proteins and RNAs that are essential in the context of B. subtilis 168.

Tryptophan, riboflavin, biotin, and thiamine are transported by transporters of the ECF (energy-coupling factor) family. The three general components are shared among all these transporters. They are listed separately with the cofactors.

FIG 1.

Outline of the metabolic model of the minimal cell. The model gives an overview of the metabolic pathways of the intended minimal organism. Functionally related pathways are grouped in boxes. Details on all reactions and enzymes are provided in Fig. 2 to 11. DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; G3P, glycerol-3-phosphate; AA, amino acid; THF, tetrahydrofolate; 2-OG, 2-oxoglutarate; GAP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PLP, pyridoxal phosphate; DHF, 7,8-dihydrofolate; pABA, 4-aminobenzoate; FMN, flavin mononucleotide; PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate; E4P, erythrose-4-phosphate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; PP, pyrophosphate; F6P, fructose-6-phosphate.

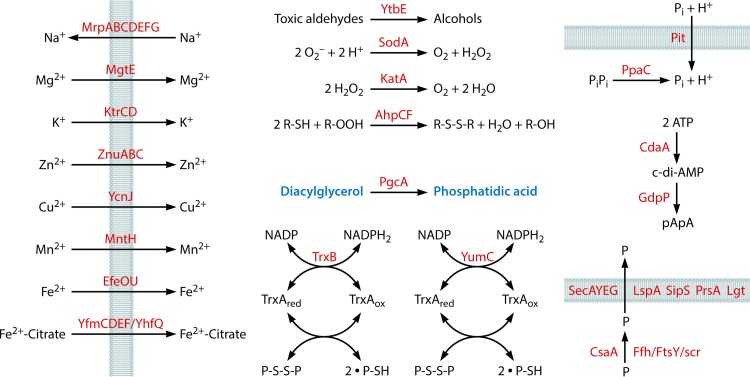

FIG 2.

Miscellaneous pathways. The model shows the uptake of metal ions and inorganic phosphate (Pi) and reactions for protective functions, for the generation of phosphatidic acid, and for the synthesis and degradation of c-di-AMP. Finally, protein secretion is included. The metabolic intermediates diacylglycerol (Fig. 6) and phosphatidic acid (Fig. 6) that occur in other pathways are labeled in blue. P, protein.

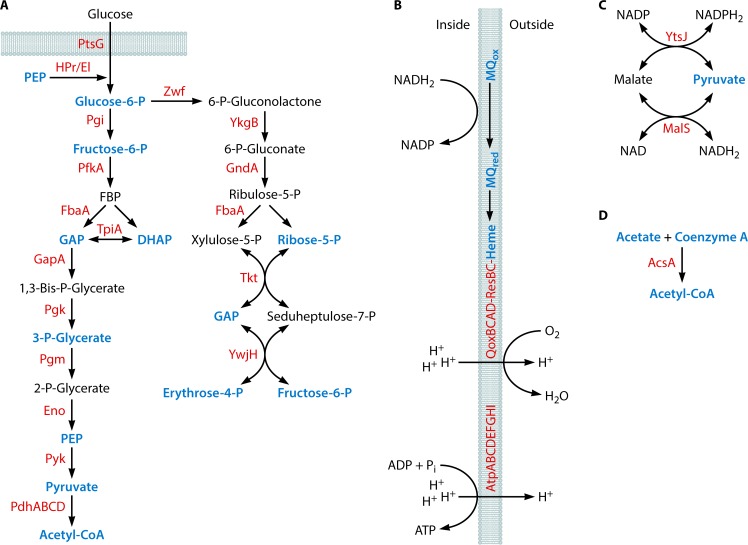

FIG 3.

Central carbon metabolism and energy conservation. (A) Glycolytic and pentose phosphate pathways. (B) The respiratory chain and ATPase. (C) The transhydrogenase cycle for balancing NADPH2. (D) Recycling of acetate derived from cell wall metabolism (Fig. 10). The following metabolic intermediates that occur in other pathways are labeled in blue: phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) (Fig. 4 and 10), glucose-6-phosphate (Glucose-6-P) (Fig. 6), fructose-6-phosphate (Fig. 10), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) (Fig. 7 and 10), dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) (Fig. 6), 3-P-Glycerate (Fig. 4), pyruvate (Fig. 4 and 8 to 10), acetyl-CoA (Fig. 6 and 10), ribose-5-phosphate (Fig. 5 and 7), erythrose-4-phosphate (Fig. 4), menaquinone/menaquinol (MQ) (Fig. 9), heme (Fig. 8), acetate (Fig. 10), and coenzyme A (Fig. 6 and 10). FBP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate.

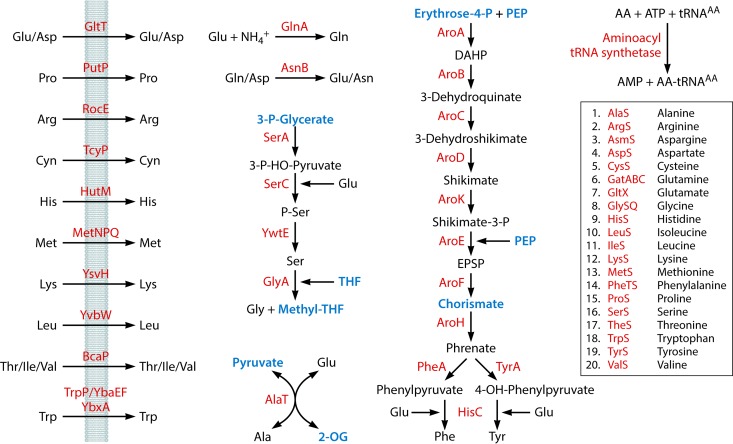

FIG 4.

Acquisition of amino acids and charging of tRNAs. The following metabolic intermediates that occur in other pathways are labeled in blue: 3-P-Glycerate (Fig. 3), tetrahydrofolate (THF) (Fig. 7 and 8), methyltetrahydrofolate (Methyl-THF) (Fig. 5 and 7), pyruvate (Fig. 3 and 8 to 10), 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG) (Fig. 9), erythrose-4-phosphate (Fig. 3), phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) (Fig. 3 and 10), and chorismate (Fig. 8 and 9). DAHP, 3-deoxy-d-arabino-hept-2-ulosonate 7-phosphate; EPSP, 5-O-(1-carboxyvinyl)-3-phosphoshikimate; AA, amino acid.

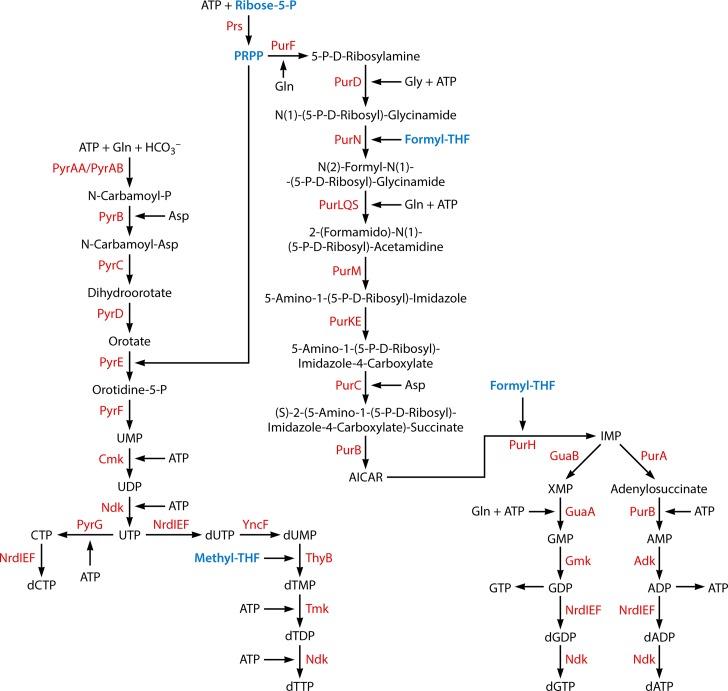

FIG 5.

Acquisition of nucleotides. The following metabolic intermediates that occur in other pathways are labeled in blue: methyltetrahydrofolate (Methyl-THF) (Fig. 4 and 7), ribose-5-phosphate (Fig. 3 and 7), phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) (Fig. 7), and formyltetrahydrofolate (Formyl-THF) (Fig. 8). AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide.

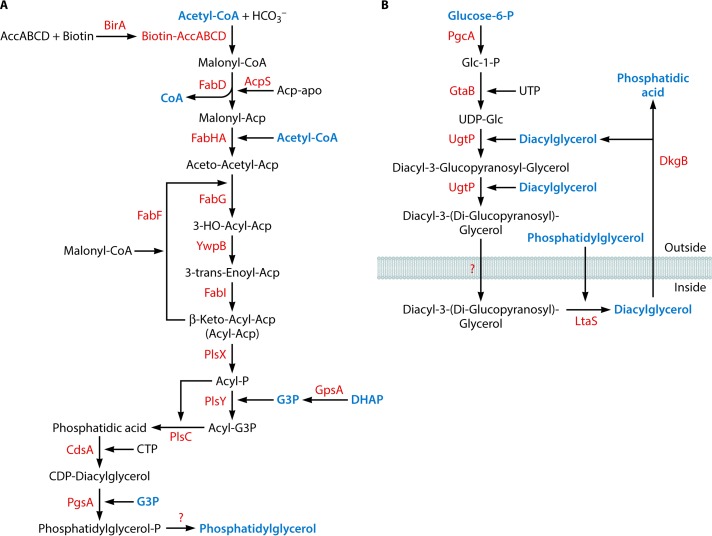

FIG 6.

(A) Biosynthesis of lipids. The enzyme required for the conversion of phosphatidylglycerol phosphate to phosphatidylglycerol is unknown. (B) Biosynthesis of lipoteichoic acids. The enzyme required for the export of diacyl-3-(diglucopyranosyl)-glycerol is unknown. The following metabolic intermediates that occur in other pathways are labeled in blue: acetyl-CoA (Fig. 3 and 10), CoA (Fig. 3, 7, and 9), glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) (Fig. 11), dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) (Fig. 3), phosphatidylglycerol (this figure), glucose-6-phosphate (Fig. 3), diacylglycerol (Fig. 2), and phosphatidic acid (Fig. 2).

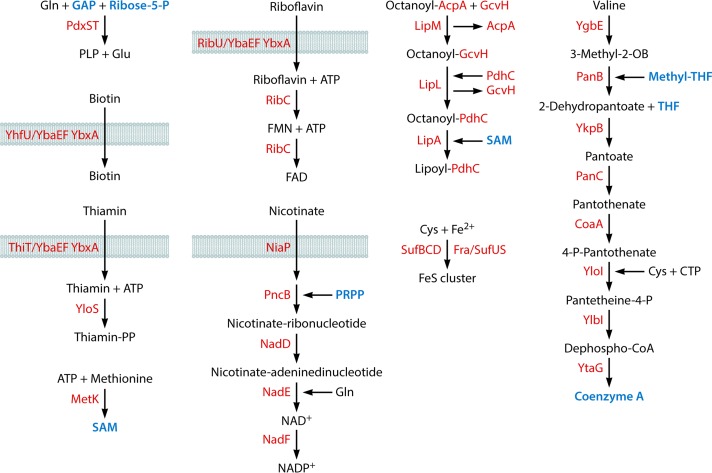

FIG 7.

Acquisition of cofactors and biosynthesis of iron-sulfur clusters. The following metabolic intermediates that occur in other pathways are labeled in blue: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) (Fig. 3 and 10), ribose-5-phosphate (Fig. 3 and 5), S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) (this figure), phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) (Fig. 5), methyltetrahydrofolate (Methyl-THF) (Fig. 4 and 5), tetrahydrofolate (THF) (Fig. 4 and 8), and coenzyme A (CoA) (Fig. 3, 6, and 9). PLP, pyridoxal phosphate; FMN, flavin mononucleotide; FeS, iron-sulfur cluster; 3-Methyl-2-OB, 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate.

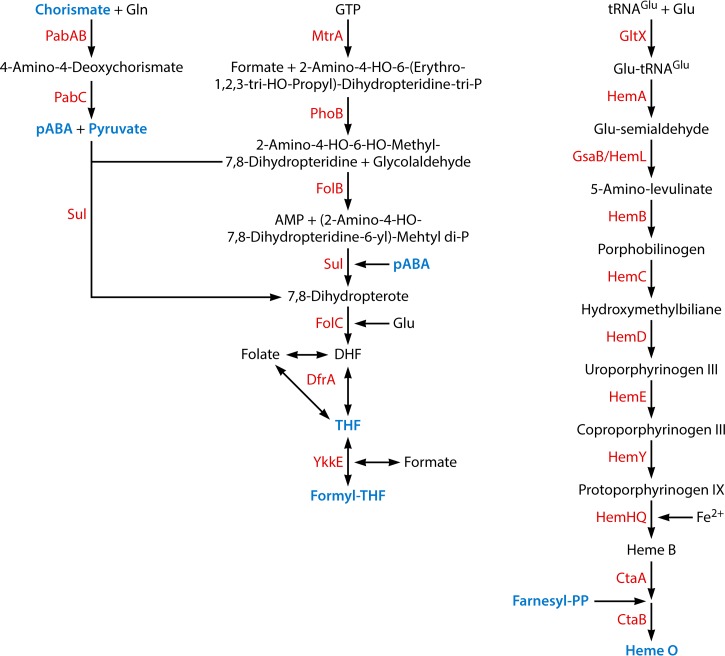

FIG 8.

Acquisition of cofactors. The following met1abolic intermediates that occur in other pathways are labeled in blue: chorismate (Fig. 4 and 9), 4-aminobenzoate (pABA) (this figure), pyruvate (Fig. 3, 4, 9, and 10), tetrahydrofolate (THF) (Fig. 4 and 7), formyltetrahydrofolate (Formyl-THF) (Fig. 5), farnesyl pyrophosphate (farnesyl-PP) (Fig. 10), and heme O (Fig. 3). DHF, 7,8-dihydrofolate.

FIG 9.

Acquisition of cofactors. The following metabolic intermediates that occur in other pathways are labeled in blue: chorismate (Fig. 4 and 8), 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG) (Fig. 4), pyruvate (Fig. 3, 4, 8, and 10), coenzyme A (CoA) (Fig. 3, 6, and 7), and menaquinone (Fig. 3).

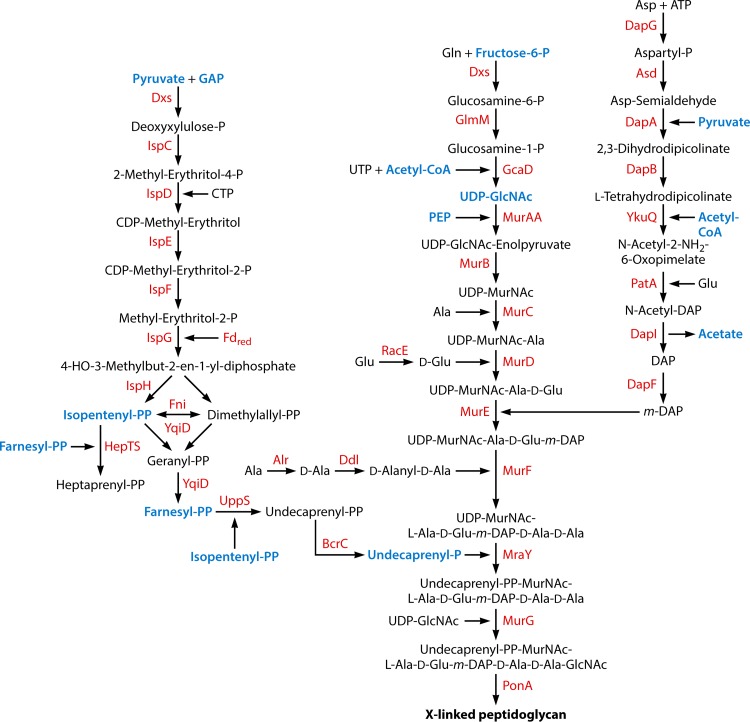

FIG 10.

Biosynthesis of the cell wall. The following metabolic intermediates that occur in other pathways are labeled in blue: pyruvate (Fig. 3, 4, 8, and 9), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) (Fig. 3 and 7), isopentenyl pyrophosphate (isopentenyl-PP) (this figure), farnesyl pyrophosphate (farnesyl-PP) (Fig. 8), undecaprenyl phosphate (Fig. 11), fructose-6-phosphate (Fig. 3), acetyl-CoA (Fig. 3 and 6), UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) (Fig. 11), phosphoenol pyrophosphate (PEP) (Fig. 3 and 4), and acetate (Fig. 3). UDP-MurNAc, UDP-N-acetylmuramic acid; DAP, diaminopimelate.

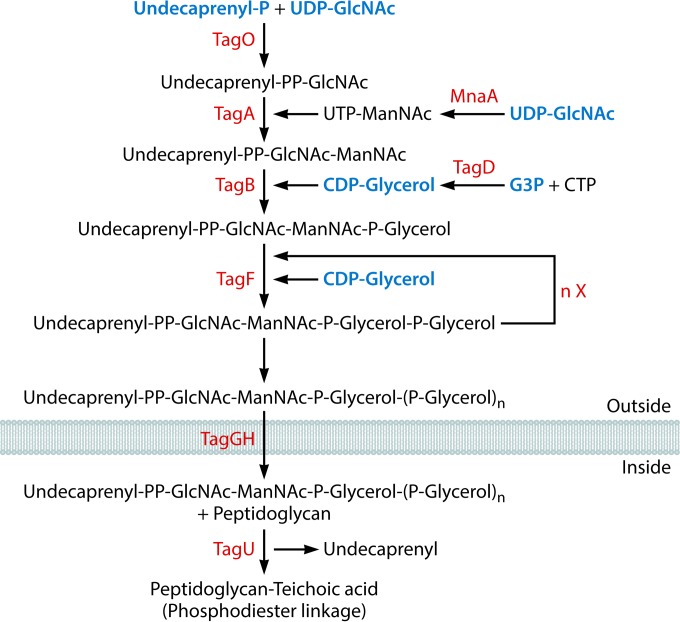

FIG 11.

Biosynthesis of wall teichoic acids. The following metabolic intermediates that occur in other pathways are labeled in blue: undecaprenyl phosphate (Fig. 10), UDP N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) (Fig. 10), CDP-glycerol (this figure), and glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) (Fig. 6). UDP-ManNAc, UDP-N-acetylmannosamine.

TABLE 2.

The complete gene set of MiniBacilluse

| Gene | BSU no.a | Essentialb | Syn3.0c | EC no. | PDB accession no. | Organismd | Function(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information | |||||||

| DNA replication | |||||||

| dnaA | BSU00010 | Yes | Yes | 2Z4R | Thermotoga maritima | Replication initiation protein | |

| dnaB | BSU28990 | Yes | Initiation of chromosome replication | ||||

| dnaC | BSU40440 | Yes | Yes | 3.6.4.12 | 2VYE | Geobacillus kaustophilus | Replicative DNA helicase |

| dnaD | BSU22350 | Yes | 2V79 | B. subtilis | Initiation of chromosome replication | ||

| dnaE | BSU29230 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.7.7 | 3E0D | Thermus aquaticus | DNA polymerase III (alpha subunit) |

| dnaG | BSU25210 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.7.- | 4E2K | S. aureus | DNA primase |

| dnaI | BSU28980 | Yes | Yes | 4M4W | B. subtilis | Primosome component (helicase loader) | |

| dnaN | BSU00020 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.7.7 | 4TR6 | B. subtilis | DNA polymerase III (beta subunit), beta clamp |

| dnaX | BSU00190 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.7.7 | 1JR3 | E. coli | DNA polymerase III (gamma and tau subunits) |

| holA | BSU25560 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.7.7 | 3ZH9 | B. subtilis | DNA polymerase III, delta subunit |

| holB | BSU00310 | Yes | 2.7.7.7 | 1NJG | E. coli | DNA polymerase III (delta subunit) | |

| ligA | BSU06620 | Yes | Yes | 6.5.1.2 | 2OWO | E. coli | DNA ligase (NAD dependent) |

| priA | BSU15710 | Yes | 3.6.4.- | 4NL4 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Primosomal replication factor Y | |

| polC | BSU16580 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.7.7 | 3F2B | G. kaustophilus | DNA polymerase III (alpha subunit) |

| rtp | BSU18490 | No | 1BM9 | B. subtilis | Replication terminator protein | ||

| ssbA | BSU40900 | Yes | Yes | 3VDY | B. subtilis | Single-strand DNA-binding protein | |

| yabA | BSU00330 | No | 5DOL | B. subtilis | Inhibitor of DnaA oligomerization | ||

| polA | BSU29090 | No | Yes | 2.7.7.7 | 1BGX | T. aquaticus | DNA polymerase I |

| Chromosome maintenance | |||||||

| scpA | BSU23220 | Yes | 3ZGX | B. subtilis | DNA segregation/condensation protein | ||

| scpB | BSU23210 | Yes | Yes | 3W6J | Geobacillus stearothermophilus | DNA segregation/condensation protein | |

| smc | BSU15940 | Yes | Yes | 3ZGX | B. subtilis | SMC protein | |

| parE | BSU18090 | Yes | Yes | 5.99.1.- | 4I3H | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV |

| parC | BSU18100 | Yes | Yes | 5.99.1.- | 2INR | S. aureus | Subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV |

| spoIIIE | BSU16800 | No | 2IUT | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATP-dependent DNA translocase | ||

| sftA | BSU29805 | No | 2IUT | P. aeruginosa | DNA translocase | ||

| codV | BSU16140 | No | 1A0P | E. coli | Site-specific integrase/recombinase | ||

| ripX | BSU23510 | No | 1A0P | E. coli | Site-specific integrase/recombinase | ||

| gyrB | BSU00060 | Yes | Yes | 5.99.1.3 | 4I3H | S. pneumoniae | DNA gyrase (subunit B) |

| gyrA | BSU00070 | Yes | Yes | 5.99.1.3 | 4DDQ | B. subtilis | DNA gyrase (subunit A) |

| topA | BSU16120 | Yes | Yes | 5.99.1.2 | 4RUL | E. coli | DNA topoisomerase I |

| hbs | BSU22790 | Yes | 1HUE | G. stearothermophilus | Nonspecific DNA-binding protein HBsu | ||

| Transcription | |||||||

| rpoA | BSU01430 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.7.6 | 3IYD | E. coli | RNA polymerase alpha subunit |

| rpoB | BSU01070 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.7.6 | 3IYD | E. coli | RNA polymerase beta subunit |

| rpoC | BSU01080 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.7.6 | 3IYD | E. coli | RNA polymerase beta′ subunit |

| sigA | BSU25200 | Yes | Yes | 3IYD | E. coli | RNA polymerase sigma factor SigA | |

| rpoE | BSU37160 | No | 2.7.7.6 | 2KRC | B. subtilis | RNA polymerase delta subunit | |

| helD | BSU33450 | No | 3.6.4.12 | DNA 3′–5′ helicase IV | |||

| greA | BSU27320 | No | Yes | 1GRJ | E. coli | Transcription elongation factor | |

| nusA | BSU16600 | Yes | Yes | 1HH2 | T. maritima | Transcription termination factor | |

| RNA folding and degradation | |||||||

| cspD | BSU21930 | No | 1C9O | Bacillus caldolyticus | Cold shock protein | ||

| cspB | BSU09100 | No | 2ES2 | B. subtilis | Major cold shock protein | ||

| rny | BSU16960 | No | Yes | 3.1.4.16 | RNase Y | ||

| rnjA | BSU14530 | Yes | Yes | 3ZQ4 | B. subtilis | RNase J1 | |

| pnpA | BSU16690 | No | 2.7.7.8 | 3CDI | E. coli | Polynucleotide phosphorylase | |

| nrnA | BSU29250 | No | Yes | 3.1.3.7 | 3DEV | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | Oligoribonuclease (nano-RNase) |

| Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases | |||||||

| alaS | BSU27410 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.7 | 3HTZ | E. coli | Alanine-tRNA synthetase |

| argS | BSU37330 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.19 | 3FNR | Campylobacter jejuni | Arginyl-tRNA synthetase, universally conserved protein |

| asnS | BSU22360 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.22 | 1X54 | Pyrococcus horikoshii | Asparagyl-tRNA synthetase |

| aspS | BSU27550 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.12 | 1EQR | E. coli | Aspartyl-tRNA synthetase |

| cysS | BSU00940 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.16 | 3TQO | Coxiella burnetii | Cysteine-tRNA synthetase |

| gatC | BSU06670 | Yes | 6.3.5.7 | 2DF4 | S. aureus | Production of glutamyl-tRNAGln | |

| gatA | BSU06680 | Yes | Yes | 6.3.5.7 | 2DF4 | S. aureus | Production of glutamyl-tRNAGln |

| gatB | BSU06690 | Yes | Yes | 6.3.5.7 | 2DF4 | S. aureus | Production of glutamyl-tRNAGln |

| gltX | BSU00920 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.17 | 2O5R | T. maritima | Glutamyl-tRNA synthetase, universally conserved protein |

| glyS | BSU25260 | Yes | 6.1.1.14 | Glycyl-tRNA synthetase (beta subunit) | |||

| glyQ | BSU25270 | Yes | 6.1.1.14 | 1J5W | T. maritima | Glycyl-tRNA synthetase (alpha subunit) | |

| hisS | BSU27560 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.21 | 1QE0 | S. aureus | Histidyl-tRNA synthetase |

| ileS | BSU15430 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.5 | 1QU2 | S. aureus | Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase |

| leuS | BSU30320 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.4 | 1OBH | Thermus thermophilus | Leucyl-tRNA synthetase |

| lysS | BSU00820 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.6 | 3E9H | G. stearothermophilus | Lysyl-tRNA synthetase |

| metS | BSU00380 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.10 | 4QRD | S. aureus | Methionyl-tRNA synthetase |

| pheT | BSU28630 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.20 | 2RHS | S. haemolyticus | Phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase (beta subunit) |

| pheS | BSU28640 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.20 | 2RHQ | S. haemolyticus | Phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase (alpha subunit), universally conserved protein |

| proS | BSU16570 | Yes | 6.1.1.15 | 2J3L | Enterococcus faecalis | Prolyl-tRNA synthetase | |

| serS | BSU00130 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.11 | 2DQ3 | Aquifex aeolicus | Seryl-tRNA synthetase |

| thrS | BSU28950 | No | Yes | 6.1.1.3 | 1NYQ | S. aureus | Threonyl-tRNA synthetase (major) |

| trpS | BSU11420 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.2 | 3PRH | B. subtilis | Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase |

| tyrS | BSU29670 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.1 | 2TS1 | G. stearothermophilus | Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (major) |

| valS | BSU28090 | Yes | Yes | 6.1.1.9 | 1GAX | T. thermophilus | Valyl-tRNA synthetase |

| Ribosomal proteins | |||||||

| rplA | BSU01030 | No | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L1 | |

| rplB | BSU01190 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L2 | |

| rplC | BSU01160 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L3 | |

| rplD | BSU01170 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L4 | |

| rplE | BSU01280 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L5 | |

| rplF | BSU01310 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L6 | |

| rplI | BSU40500 | No | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L9 | |

| rplJ | BSU01040 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L10 | |

| rplK | BSU01020 | No | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L11 | |

| rplL | BSU01050 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L12 | |

| rplM | BSU01490 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L13 | |

| rplN | BSU01260 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L14 | |

| rplO | BSU01350 | No | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L15 | |

| rplP | BSU01230 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L16 | |

| rplQ | BSU01440 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L17 | |

| rplR | BSU01320 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L18 | |

| rplS | BSU16040 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L19 | |

| rplT | BSU28850 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L20 | |

| rplU | BSU27960 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L21 | |

| rplV | BSU01210 | No | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L22 | |

| rplW | BSU01180 | No | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L23 | |

| rplX | BSU01270 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L24 | |

| rpmA | BSU27940 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L27 | |

| rpmB | BSU15820 | No | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L28 | ||

| rpmC | BSU01240 | No | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L29 | ||

| rpmD | BSU01340 | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L30 | ||

| rpmE | BSU37070 | No | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L31 | ||

| rpmF | BSU15080 | No | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L32 | ||

| rpmGA | BSU24900 | No | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L33a | ||

| rpmGB | BSU00990 | No | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L33b | ||

| rpmH | BSU41060 | No | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L34 | ||

| rpmI | BSU28860 | No | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L35 | ||

| rpmJ | BSU01400 | No | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein L36 | |

| rpsB | BSU16490 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S2 | |

| rpsC | BSU01220 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S3 | |

| rpsD | BSU29660 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S4 | |

| rpsE | BSU01330 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S5 | |

| rpsF | BSU40910 | No | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S6 | |

| rpsG | BSU01110 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S7 | |

| rpsH | BSU01300 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S8 | |

| rpsI | BSU01500 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S9 | |

| rpsJ | BSU01150 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S10 | |

| rpsK | BSU01420 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S11 | |

| rpsL | BSU01100 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S12 | |

| rpsM | BSU01410 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S13 | |

| rpsN | BSU01290 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S14 | |

| rpsO | BSU16680 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S15 | |

| rpsP | BSU15990 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S16 | |

| rpsQ | BSU01250 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S17 | |

| rpsR | BSU40890 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S18 | |

| rpsS | BSU01200 | Yes | Yes | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S19 | |

| rpsT | BSU25550 | No | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S20 | ||

| rpsU | BSU25410 | No | 3J9W | B. subtilis | Ribosomal protein S21 | ||

| rRNA/tRNA maturation and modification | |||||||

| rnpA | BSU41050 | Yes | Yes | 3.1.26.5 | 3Q1R | T. maritima | Protein component of RNase P |

| rnpB | BSU_misc_RNA_35 | Yes | 3Q1R | T. maritima | RNA component of RNase P | ||

| rnz | BSU23840 | Yes | 3.1.26.11 | 4GCW | B. subtilis | RNase Z | |

| rph | BSU28370 | No | 2.7.7.56 | 1OYP | B. subtilis | RNase PH | |

| rbfA | BSU16650 | No | 1JOS | Haemophilus influenzae | Ribosome-binding factor A | ||

| rimM | BSU16020 | No | 3H9N | H. influenzae | 16S rRNA-processing protein, RNase | ||

| cca | BSU22450 | Yes | 2.7.7.25 | 1MIY | G. stearothermophilus | tRNA nucleotidyltransferase | |

| fmt | BSU15730 | Yes | Yes | 2.1.2.9 | 4IQF | Bacillus anthracis | Methionyl-tRNA formyltransferase |

| folD | BSU24310 | Yes | Yes | 1.5.1.5 | 1B0A | E. coli | Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase |

| rlmCD | BSU06730 | No | 2.1.1.190 | 2BH2 | E. coli | rRNA methyltransferase | |

| ysgA | BSU28650 | Yes | Yes | 2.1.1.- | 4X3M | T. thermophilus | Similar to rRNA methylase |

| mraW | BSU15140 | No | Yes | 2.1.1.199 | 1WG8 | T. thermophilus | SAM-dependent methyltransferase |

| cspR | BSU08930 | Yes | 2.1.1.- | 4PZK | B. anthracis | Similar to tRNA(Um34/Cm34) methyltransferase | |

| trmD | BSU16030 | Yes | Yes | 2.1.1.31 | 3KY7 | S. aureus | tRNA methyltransferase |

| trmU | BSU27500 | Yes | Yes | 2.8.1.- | 2HMA | S. pneumoniae | tRNA(5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridylate) methyltransferase |

| yrvO | BSU27510 | Yes | 2.8.1.7 | 1P3W | E. coli | Cysteine desulfurase | |

| yacO | BSU00960 | No | Yes | 2.1.1.- | 1GZ0 | E. coli | Putative 23S rRNA methyltransferase |

| ksgA | BSU00420 | No | Yes | 2.1.1.- | 3FUU | T. thermophilus | rRNA adenine dimethyltransferase |

| rluB | BSU23160 | No | Yes | 5.4.99.22 | 4LAB | E. coli | Pseudouridine synthase |

| ypuI | BSU23200 | No | rRNA pseudouridine 2633 synthase | ||||

| tilS | BSU00670 | Yes | Yes | 6.3.4.19 | 3A2K | G. kaustophilus | tRNAIle lysidine synthetase |

| tsaB | BSU05920 | Yes | 2A6A | T. maritima | Threonyl carbamoyl adenosine (t6A) modification of tRNAs that pair with ANN codons in mRNA | ||

| tsaD | BSU05940 | Yes | Yes | 2.3.1.234 | 3ZET | Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium | Threonyl carbamoyl adenosine (t6A) modification of tRNAs that pair with ANN codons in mRNA, universally conserved protein |

| tsaC | BSU36950 | No | 2.7.7.87 | 3AJE | Sulfolobus tokodaii | l-Threonyl carbamoyl AMP synthase, biosynthesis of the hypermodified base threonyl carbamoyl adenosine [t(6)A] | |

| gidA | BSU41010 | No | Yes | 3CP2 | E. coli | tRNA uridine 5-carboxymethyl-aminomethyl modification enzyme | |

| thdF | BSU41020 | No | Yes | 1XZP | T. maritima | GTP-binding protein, putative tRNA modification GTPase | |

| truA | BSU01480 | No | Yes | 5.4.99.12 | 1VS3 | T. thermophilus | Pseudouridylate synthase I, universally conserved protein |

| tsaE | BSU05910 | No | Yes | 1HTW | H. influenzae | P-loop ATPase | |

| trmFO | BSU16130 | No | Yes | 2.1.1.74 | 3G5Q | T. thermophilus | tRNA:m(5)U-54 methyltransferase |

| miaA | BSU17330 | No | 2.5.1.8 | 2QGN | Bacillus halodurans | tRNA isopentenylpyrophosphate transferase | |

| yaaJ | BSU00180 | No | 2B3J | S. aureus | tRNA-specific adenosine deaminase | ||

| ylyB | BSU15460 | No | Yes | 5.4.99.23 | 1V9F | E. coli | Similar to pseudouridylate synthase |

| Ribosome maturation/assembly | |||||||

| ydiD | BSU05930 | No | 2.3.1.128 | 2CNM | S. enterica | Similar to ribosomal protein alanine N-acetyltransferase | |

| ylxS | BSU16590 | No | 1IB8 | S. pneumoniae | Similar to 30S ribosomal subunit maturation protein | ||

| prp | BSU27950 | No | 4PEO | S. aureus | Maturation of L27 | ||

| engA | BSU22840 | Yes | 2HJG | B. subtilis | GTPase, ribosome 50S subunit assembly | ||

| era | BSU25290 | Yes | Yes | 3R9W | A. aeolicus | GTP-binding protein | |

| obg | BSU27920 | Yes | Yes | 3.6.5.- | 1LNZ | B. subtilis | GTP-binding protein |

| rbgA | BSU16050 | Yes | Yes | 1PUJ | B. subtilis | Assembly of the 50S subunit of the ribosome | |

| yqeH | BSU25670 | Yes | 3H2Y | B. anthracis | Assembly/stability of the 30S subunit of the ribosome, assembly of the 70S ribosome | ||

| ysxC | BSU28190 | Yes | Yes | 1SVI | B. subtilis | Assembly of the 50S subunit of the ribosome | |

| Translation factors | |||||||

| efp | BSU24450 | No | Yes | 1YBY | Clostridium thermocellum | Elongation factor P | |

| frr | BSU16520 | Yes | Yes | 4GFQ | B. anthracis | Ribosome recycling factor | |

| fusA | BSU01120 | Yes | Yes | 2XEX | S. aureus | Elongation factor G | |

| infA | BSU01390 | Yes | Yes | 4QL5 | S. pneumoniae | Translation initiation factor IF-1 | |

| infB | BSU16630 | Yes | Yes | 1ZO1 | E. coli | Translation initiation factor IF-2 | |

| infC | BSU28870 | Yes | Yes | 1TIG | G. stearothermophilus | Translation initiation factor IF-3 | |

| prfA | BSU37010 | Yes | Yes | 1ZBT | Streptococcus mutans | Peptide chain release factor 1 | |

| prfB | BSU35290 | Yes | 1MI6 | E. coli | Peptide chain release factor 2 | ||

| tsf | BSU16500 | Yes | Yes | 1EFU | E. coli | Elongation factor Ts | |

| tufA | BSU01130 | Yes | Yes | 3.6.5.3 | 4R71 | E. coli | Elongation factor Tu |

| lepA | BSU25510 | No | Yes | 4QJT | T. thermophilus | Elongation factor 4 | |

| Translation/others | |||||||

| map | BSU01380 | Yes | Yes | 3.4.11.18 | 1O0X | T. maritima | Methionine aminopeptidase |

| ywkE | BSU37000 | No | Yes | 2.1.1.297 | 2B3T | E. coli | Similar to N5-glutamine methyltransferase that modifies peptide release factors |

| ybxF | BSU01090 | No | 3V7E | B. subtilis | Similar to ribosomal protein L7 family | ||

| spoVC | BSU00530 | Yes | Yes | 3.1.1.29 | 4QT4 | S. pyogenes | Putative peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase |

| ssrA | BSU_MISC_RNA_55 | No | 1P6V | A. aeolicus | tmRNA | ||

| smpB | BSU33600 | No | Yes | 1P6V | A. aeolicus | tmRNA-binding protein | |

| Protein secretion | |||||||

| scr | BSU_misc_RNA_2 | Yes | 4UE5 | B. subtilis | Signal recognition particle RNA | ||

| ffh | BSU15980 | Yes | Yes | 4UE5 | B. subtilis | Signal recognition particle component | |

| ftsY | BSU15950 | No | Yes | 2XXA | E. coli | Signal recognition particle | |

| yidC2 | BSU23890 | No | 3WO6 | B. halodurans | Sec-independent membrane protein translocase | ||

| secA | BSU35300 | Yes | Yes | 3DL8 | B. subtilis | Preprotein translocase subunit (ATPase) | |

| secE | BSU01000 | Yes | 3DL8 | B. subtilis | Preprotein translocase subunit | ||

| secY | BSU01360 | Yes | Yes | 3DL8 | B. subtilis | Preprotein translocase subunit, universally conserved protein | |

| secG | BSU33630 | No | 3DL8 | B. subtilis | Preprotein translocase subunit | ||

| sipS | BSU23310 | No | 4NV4 | B. anthracis | Signal peptidase I | ||

| prsA | BSU09950 | Yes | 5.2.1.8 | 4WO7 | B. subtilis | Protein secretion (posttranslocation molecular chaperone) | |

| csaA | BSU19040 | No | 2NZH | B. subtilis | Molecular chaperone involved in protein secretion | ||

| lgt | BSU34990 | No | 2.4.99.- | 5AZB | E. coli | Prolipoprotein diacylglyceryl transferase | |

| lspA | BSU15450 | No | 5DIR | P. aeruginosa | Signal peptidase II | ||

| Proteolysis/quality control/chaperones | |||||||

| htrB | BSU33000 | No | 3QO6 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Serine protease | ||

| groES | BSU06020 | Yes | 1WE3 | T. thermophilus | Chaperonin, universally conserved protein | ||

| groEL | BSU06030 | Yes | 1WE3 | T. thermophilus | Chaperonin | ||

| dnaJ | BSU25460 | No | Yes | 3LZ8 | K. pneumoniae | Activation of DnaK | |

| dnaK | BSU25470 | No | Yes | 2V7Y | G. kaustophilus | Molecular chaperone | |

| grpE | BSU25480 | No | 4ANI | G. kaustophilus | Activation of DnaK | ||

| tig | BSU28230 | No | 2MLX | E. coli | Trigger factor (prolyl isomerase) | ||

| Metabolism | |||||||

| Central carbon metabolism | |||||||

| Glycolysis | |||||||

| ptsG | BSU13890 | No | Yes | 2.7.1.69 | PTS glucose permease, EIICBA(Glc) | ||

| ptsH | BSU13900 | No | Yes | 2.7.11.- | 2FEP | B. subtilis | HPr, general component of the PTS |

| ptsI | BSU13910 | No | Yes | 2.7.3.9 | 2WQD | S. aureus | Enzyme I, general component of the PTS |

| pgi | BSU31350 | No | Yes | 5.3.1.9 | 3IFS | B. anthracis | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase |

| pfkA | BSU29190 | No | Yes | 2.7.1.11 | 4A3S | B. subtilis | Phosphofructokinase |

| fbaA | BSU37120 | No | 4.1.2.13 | 4TO8 | S. aureus | Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase | |

| tpi | BSU33920 | No | Yes | 5.3.1.1 | 2BTM | G. stearothermophilus | Triose phosphate isomerase |

| gapA | BSU33940 | Yes | Yes | 1.2.1.12 | 1GD1 | G. stearothermophilus | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| pgk | BSU33930 | No | Yes | 2.7.2.3 | 1PHP | G. stearothermophilus | Phosphoglycerate kinase, universally conserved protein |

| pgm | BSU33910 | Yes | Yes | 5.4.2.1 | 1EJJ | G. stearothermophilus | Phosphoglycerate mutase |

| eno | BSU33900 | Yes | Yes | 4.2.1.11 | 4A3R | B. subtilis | Enolase, universally conserved protein |

| pyk | BSU29180 | No | Yes | 2.7.1.40 | 2E28 | G. stearothermophilus | Pyruvate kinase |

| pdhA | BSU14580 | Yes | Yes | 1.2.4.1 | 3DUF | G. stearothermophilus | Pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1 alpha subunit) |

| pdhB | BSU14590 | No | Yes | 1.2.4.1 | 3DUF | G. stearothermophilus | Pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1 beta subunit) |

| pdhC | BSU14600 | No | Yes | 2.3.1.12 | 3DUF | G. stearothermophilus | Pyruvate dehydrogenase (dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase E2 subunit) |

| pdhD | BSU14610 | No | Yes | 1.8.1.4 | 1EBD | G. stearothermophilus | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase E3 subunit of both pyruvate and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complexes |

| Transhydrogenation cycle | |||||||

| ytsJ | BSU29220 | No | 1.1.1.38 | 2A9F | S. pyogenes | Malic enzyme | |

| malS | BSU29880 | No | 1.1.1.38 | 1LLQ | Ascaris suum | Malate dehydrogenase (decarboxylating) | |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | |||||||

| ykgB | BSU13010 | No | 3.1.1.31 | 3HFQ | Lactobacillus plantarum | 6-Phosphogluconolactonase | |

| rpe | BSU15790 | No | Yes | 5.1.3.1 | 1TQJ | Synechocystis sp. | Ribulose 5-phosphate 3-epimerase |

| tkt | BSU17890 | No | Yes | 2.2.1.1 | 3HYL | B. anthracis | Transketolase |

| zwf | BSU23850 | No | 1.1.1.49 | 1DPG | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | |

| gndA | BSU23860 | No | 1.1.1.44 | 2W8Z | G. stearothermophilus | NADP-dependent phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | |

| ywlF | BSU36920 | No | Yes | 3HE8 | C. thermocellum | Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase | |

| ywjH | BSU37110 | No | 2.2.1.2 | 3R8R | B. subtilis | Transaldolase | |

| Recycling of acetate | |||||||

| acsA | BSU29680 | No | 6.2.1.1 | 2P2F | S. enterica | Acetyl-CoA synthetase | |

| Respiration/energy | |||||||

| ndh | BSU12290 | No | 4NWZ | Caldalkalibacillus thermarum | NADH dehydrogenase | ||

| Cytochrome aa3 | |||||||

| qoxD | BSU38140 | No | Cytochrome aa3 quinol oxidase (subunit IV) | ||||

| qoxC | BSU38150 | No | 1FFT | E. coli | Cytochrome aa3 quinol oxidase (subunit III) | ||

| qoxB | BSU38160 | No | 1FFT | E. coli | Cytochrome aa3 quinol oxidase (subunit I) | ||

| qoxA | BSU38170 | No | 1FFT | E. coli | Cytochrome aa3 quinol oxidase (subunit II) | ||

| Cytochrome maturation | |||||||

| resC | BSU23130 | Yes | Part of heme translocase, required for cytochrome c synthesis | ||||

| resB | BSU23140 | Yes | Part of heme translocase, required for cytochrome c synthesis | ||||

| ATPase | |||||||

| atpC | BSU36800 | No | 2E5Y | Bacillus sp. | ATP synthase, F1 (subunit epsilon) | ||

| atpD | BSU36810 | No | Yes | 3.6.3.14 | 1SKY | Bacillus sp. | ATP synthase, F1 (subunit beta) |

| atpG | BSU36820 | No | Yes | 4XD7 | G. kaustophilus | ATP synthase, F1 (subunit gamma) | |

| atpA | BSU36830 | No | Yes | 3.6.3.14 | 1SKY | Bacillus sp. | ATP synthase, F1 (subunit alpha) |

| atpH | BSU36840 | No | ATP synthase, F1 (subunit delta) | ||||

| atpF | BSU36850 | No | Yes | ATP synthase, Fo (subunit b) | |||

| atpE | BSU36860 | No | 1WU0 | Bacillus sp. | ATP synthase, Fo (subunit c) | ||

| atpB | BSU36870 | No | 1C17 | E. coli | ATP synthase, Fo (subunit a) | ||

| atpI | BSU36880 | No | ATP synthase (subunit i) | ||||

| Amino acids | |||||||

| Asp, Glu | |||||||

| gltT | BSU10220 | No | 3V8F | P. horikoshii | Major H+/Na+-glutamate symport protein | ||

| Arg | |||||||

| rocE | BSU40330 | No | 3LRB | E. coli | Amino acid permease | ||

| Pro | |||||||

| putP | BSU03220 | No | 2XQ2 | Vibrio parahaemolyticus | High-affinity proline permease | ||

| Trp | |||||||

| trpP | BSU10010 | No | S protein of tryptophan ECF transporter | ||||

| Met | |||||||

| metQ | BSU32730 | No | 4GOT | B. subtilis | Methionine ABC transporter (binding lipoprotein) | ||

| metP | BSU32740 | No | 3DHW | E. coli | Methionine ABC transporter, permease | ||

| metN | BSU32750 | No | 3DHW | E. coli | Methionine ABC transporter (ATP-binding protein) | ||

| His | |||||||

| hutM | BSU39390 | No | Histidine permease | ||||

| Cys | |||||||

| tcyP | BSU09130 | No | Yes | 3KBC | P. horikoshii | Cystine transporter | |

| Gly | |||||||

| glyA | BSU36900 | Yes | Yes | 2.1.2.1 | 1KKJ | G. stearothermophilus | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase |

| Ile, Val, Thr | |||||||

| bcaP | BSU09460 | No | Branched-chain amino acid transporter | ||||

| Lys | |||||||

| yvsH | BSU33330 | No | 3LRB | E. coli | Putative lysine transporter | ||

| Chorismate for aromatic amino acids, menaquinone, and folate | |||||||

| aroA | BSU29750 | No | 2.5.1.54 | 3NVT | L. monocytogenes | 3-Deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase/chorismate mutase isozyme 3 | |

| aroB | BSU22700 | No | 4.2.3.4 | 3CLH | Helicobacter pylori | 3-Dehydroquinate synthase | |

| aroC | BSU23080 | No | 4.2.1.10 | 1QFE | S. enterica serovar Typhi | 3-Dehydroquinate dehydratase | |

| aroD | BSU25660 | No | 1.1.1.25 | 2EGG | G. kaustophilus | Shikimate dehydrogenase | |

| aroE | BSU22600 | No | 2.5.1.19 | 3RMT | B. halodurans | 3-Phosphoshikimate 1-carboxyvinyltransferase | |

| aroF | BSU22710 | No | 4.2.3.5 | 1Q1L | A. aeolicus | Chorismate synthase | |

| aroK | BSU03150 | No | 2.7.1.71 | 2PT5 | A. aeolicus | Shikimate kinase | |

| Phe, Tyr | |||||||

| pheA | BSU27900 | No | 4.2.1.51 | 4LUB | S. mutans | Prephenate dehydratase | |

| hisC | BSU22620 | No | 2.6.1.9 | 3FFH | Listeria innocua | Histidinol-phosphate aminotransferase/tyrosine and phenylalanine aminotransferase | |

| aroH | BSU22690 | No | 1COM | B. subtilis | Chorismate mutase (isozymes 1 and 2) | ||

| tyrA | BSU22610 | No | 1.3.1.12 | 3DZB | Streptococcus thermophilus | Prephenate dehydrogenase | |

| Asn | |||||||

| asnB | BSU30540 | No | 6.3.5.4 | 1CT9 | E. coli | Asparagine synthase (glutamine hydrolyzing) | |

| Ala, Ser | |||||||

| alaT | BSU31400 | No | 2.6.1.- | 1DJU | P. horikoshii | Alanine aminotransferase | |

| serA | BSU23070 | No | 1.1.1.95 | 1YGY | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | |

| serC | BSU10020 | No | 2.6.1.52 | 1W23 | Bacillus alcalophilus | 3-Phosphoserine aminotransferase | |

| ywtE | BSU35850 | No | 1NRW | B. subtilis | Putative phosphatase | ||

| Leu | |||||||

| yvbW | BSU34010 | No | 3GI9 | Methanocaldococcus jannaschii | Putative leucine permease | ||

| Gln | |||||||

| glnA | BSU17460 | No | 6.3.1.2 | 4S0R | B. subtilis | Glutamine synthetase | |

| Nucleotides/phosphate | |||||||

| PRPP | |||||||

| prs | BSU00510 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.6.1 | 1DKR | B. subtilis | Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase, universally conserved protein |

| Pyrimidine biosynthesis | |||||||

| pyrAA | BSU15510 | No | 6.3.5.5 | 1JDB | E. coli | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase (glutaminase subunit) | |

| pyrAB | BSU15520 | No | 6.3.5.5 | 1JDB | E. coli | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase (catalytic subunit) | |

| pyrB | BSU15490 | No | 2.1.3.2 | 3R7D | B. subtilis | Aspartate carbamoyltransferase | |

| pyrC | BSU15500 | No | 3.5.2.3 | 3MPG | B. anthracis | Dihydro-orotase | |

| pyrD | BSU15540 | No | 1.3.3.1 | 1EP1 | Lactococcus lactis | Dihydro-orotic acid dehydrogenase (catalytic subunit) | |

| pyrE | BSU15560 | No | 2.4.2.10 | 3M3H | B. anthracis | Orotate phosphoribosyltransferase | |

| pyrF | BSU15550 | No | 4.1.1.23 | 1DBT | B. subtilis | Orotidine 5′-phosphate decarboxylase | |

| cmk | BSU22890 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.4.14 | 1Q3T | S. pneumoniae | Cytidylate kinase (CMP, dCMP) |

| pyrG | BSU37150 | Yes | Yes | 6.3.4.2 | 1S1M | E. coli | CTP synthase (NH3, glutamine) |

| yncF | BSU17660 | No | 2XCD | B. subtilis | dUTPase | ||

| thyB | BSU21820 | No | 2.1.1.45 | 3IX6 | Brucella melitensis | Thymidylate synthase B | |

| tmk | BSU00280 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.4.9 | 2CCJ | S. aureus | Thymidylate kinase |

| Purine biosynthesis | |||||||

| purF | BSU06490 | No | 2.4.2.14 | 1GPH | B. subtilis | Glutamine phosphoribosyldiphosphate amidotransferase | |

| purD | BSU06530 | No | 6.3.4.13 | 2XD4 | B. subtilis | Phosphoribosylglycinamide synthetase | |

| purN | BSU06510 | No | 2.1.2.2 | 3AV3 | G. kaustophilus | Phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase | |

| purS | BSU06460 | No | 1TWJ | B. subtilis | Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase | ||

| purQ | BSU06470 | No | 6.3.5.3 | 3D54 | T. maritima | Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase | |

| purL | BSU06480 | No | 6.3.5.3 | 3VIU | T. thermophilus | Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase | |

| purM | BSU06500 | No | 6.3.3.1 | 2BTU | B. anthracis | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole synthetase | |

| purE | BSU06420 | No | 4.1.1.21 | 1XMP | B. anthracis | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase (ATP dependent) | |

| purK | BSU06430 | No | 4.1.1.21 | 4DLK | B. anthracis | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase (ATP dependent) | |

| purC | BSU06450 | No | 6.3.2.6 | 2YWV | G. kaustophilus | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole succinocarboxamide synthase | |

| purB | BSU06440 | No | 4.3.2.2 | 1F1O | B. subtilis | Adenylsuccinate lyase | |

| purH | BSU06520 | No | 2.1.2.3 | 3ZZM | M. tuberculosis | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxamide formyltransferase | |

| guaB | BSU00090 | Yes | 1.1.1.205 | 3TSB | B. anthracis | IMP dehydrogenase | |

| guaA | BSU06360 | No | 6.3.5.2 | 1GPM | E. coli | GMP synthase (glutamine hydrolyzing) | |

| gmk | BSU15680 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.4.8 | 3TAU | L. monocytogenes | Guanylate kinase (GMP:dATP, dGMP:ATP) |

| purA | BSU40420 | No | 6.3.4.4 | 4M0G | B. anthracis | Adenylosuccinate synthetase | |

| adk | BSU01370 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.4.3 | 1P3J | B. subtilis | Adenylate kinase |

| Pyrimidine/purine biosynthesis | |||||||

| nrdE | BSU17380 | Yes | Yes | 1PEM | S. enterica | Ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase (major subunit) | |

| nrdF | BSU17390 | Yes | Yes | 4DR0 | B. subtilis | Ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase (major subunit) | |

| nrdI | BSU17370 | Yes | 1RLJ | B. subtilis | Ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase | ||

| ndk | BSU22730 | No | 2.7.4.6 | 2VU5 | B. anthracis | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | |

| hprT | BSU00680 | Yes | Yes | 2.4.2.8 | 3H83 | B. anthracis | Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase |

| Phosphate | |||||||

| pit | BSU12840 | No | Low-affinity inorganic phosphate transporter | ||||

| Lipids | |||||||

| Malonyl-CoA synthesis | |||||||

| accC | BSU24340 | Yes | 6.3.4.14 | 2VPQ | S. aureus | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (biotin carboxylase subunit) | |

| accB | BSU24350 | Yes | 6.4.1.2 | 4HR7 | E. coli | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (biotin carboxyl carrier subunit) | |

| accA | BSU29200 | Yes | 6.4.1.2 | 2F9I | S. aureus | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (alpha subunit) | |

| accD | BSU29210 | Yes | 6.4.1.2 | 2F9I | S. aureus | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (beta subunit) | |

| birA | BSU22440 | Yes | 6.3.4.15 | 3RIR | S. aureus | Biotin protein ligase | |

| Acyl carrier | |||||||

| acpS | BSU04620 | Yes | 2.7.8.7 | 1F80 | B. subtilis | Acyl carrier protein synthase, 4′-phosphopantetheine transferase | |

| acpA | BSU15920 | Yes | 1F80 | B. subtilis | Acyl carrier protein | ||

| Aceto-acyl-Acp synthesis | |||||||

| fabD | BSU15900 | Yes | 2.3.1.39 | 3QAT | Bartonella henselae | Malonyl-CoA—acyl carrier protein transacylase | |

| fabHA | BSU11330 | No | 2.3.1.180 | 1ZOW | S. aureus | Beta-ketoacyl–acyl carrier protein synthase III | |

| β-Ketoacyl-Acp chain elongation | |||||||

| fabG | BSU15910 | Yes | 1.1.1.100 | 2UVD | B. anthracis | Beta-ketoacyl–acyl carrier protein reductase | |

| fabF | BSU11340 | Yes | 2.3.1.179 | 4LS5 | B. subtilis | Beta-ketoacyl–acyl carrier protein synthase II | |

| fabI | BSU11720 | No | 1.3.1.9 | 3OIF | B. subtilis | Enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase | |

| ywpB | BSU36370 | Yes | 1U1Z | P. aeruginosa | β-Hydroxyacyl (acyl carrier protein) dehydratase | ||

| Phosphatidic acid synthesis | |||||||

| plsC | BSU09540 | Yes | 2.3.1.51 | Acyl-ACP:1-acylglycerolphosphate acyltransferase | |||

| plsX | BSU15890 | Yes | Yes | 1VI1 | B. subtilis | Acyl-ACP:phosphate acyltransferase | |

| plsY | BSU18070 | Yes | Yes | Acylphosphate:glycerol-phosphate acyltransferase | |||

| gpsA | BSU22830 | Yes | 1.1.1.94 | 1Z82 | T. maritima | Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (NAD) | |

| Phosphatidylglycerol phosphate synthesis | |||||||

| cdsA | BSU16540 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.7.41 | 4Q2G | T. maritima | Phosphatidate cytidylyltransferase |

| pgsA | BSU16920 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.8.5 | Phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase | ||

| Cofactors | |||||||

| ECF transporter (general component) for riboflavin, biotin, thiamine, tryptophan | |||||||

| ybxA | BSU01450 | No | Yes | 4HUQ | Lactobacillus brevis | ATP-binding A1 component of ECF transporters | |

| ybaE | BSU01460 | No | Yes | 4HUQ | L. brevis | ATP-binding A2 component of ECF transporters | |

| ybaF | BSU01470 | No | Yes | 4HUQ | L. brevis | Transmembrane T component of ECF transporters | |

| NAD | |||||||

| nadD | BSU25640 | Yes | 2.7.7.18 | 1KAM | B. subtilis | Nicotinamide-nucleotide adenylyltransferase | |

| nadE | BSU03130 | Yes | Yes | 6.3.1.5 | 1NSY | B. subtilis | NH3-dependent NAD+ synthetase |

| nadF | BSU11610 | Yes | Yes | 2.7.1.23 | 2I1W | L. monocytogenes | NAD kinase |

| niaP | BSU02950 | No | 4J05 | Piriformospora indica | Nicotinate transporter | ||

| pncB | BSU31750 | Yes | 2.4.2.11 | 2F7F | E. faecalis | Putative nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase | |

| Riboflavin/FAD | |||||||

| ribC | BSU16670 | Yes | 2.7.1.26 | 3OP1 | S. pneumoniae | Riboflavin kinase/FAD synthase | |

| ribU | BSU23050 | No | 3P5N | S. aureus | Riboflavin ECF transporter, S protein | ||

| Pyridoxal phosphate | |||||||

| pdxS | BSU00110 | No | 2NV2 | B. subtilis | Pyridoxal-5′-phosphate synthase (synthase domain) | ||

| pdxT | BSU00120 | No | 2NV2 | B. subtilis | Pyridoxal-5′-phosphate synthase (glutaminase domain) | ||

| Biotin | |||||||

| yhfU | BSU10370 | No | 4DVE | L. lactis | S protein of biotin ECF transporter | ||

| Thiamine, TPP | |||||||

| yloS | BSU15800 | No | 2.7.6.2 | 3LM8 | B. subtilis | Thiamine pyrophosphokinase | |

| thiT | BSU30990 | No | 4MES | L. lactis | S protein of thiamine ECF transporter | ||

| Lipoate | |||||||

| gcvH | BSU32800 | No | 3IFT | M. tuberculosis | Glycine cleavage system protein H, 2-oxo acid dehydrogenase | ||

| lipM | BSU24530 | No | 3A7A | E. coli | Octanoyltransferase | ||

| lipL | BSU37640 | No | 2P5I | B. halodurans | GcvH:E2 amidotransferase | ||

| lipA | BSU32330 | Yes | 2.8.1.8 | 4U0O | T. elongatus | Lipoic acid synthase | |

| CoA | |||||||

| ykpB | BSU14440 | No | 3HN2 | Geobacter metallireducens | Putative ketopantoate reductase | ||

| panD | BSU22410 | No | 4.1.1.11 | 2C45 | M. tuberculosis | Aspartate 1-decarboxylase | |

| panC | BSU22420 | No | 6.3.2.1 | 2X3F | S. aureus | Pantothenate synthase | |

| panB | BSU22430 | No | 2.1.2.11 | 1M3U | E. coli | 3-Methyl-2-oxobutanoate hydroxymethyltransferase | |

| ybgE | BSU02390 | No | 2.6.1.42 | 3HT5 | M. tuberculosis | Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase | |

| coaA | BSU23760 | No | 2.7.1.33 | 4F7W | K. pneumoniae | Probable pantothenate kinase | |

| yloI | BSU15700 | No | 4.1.1.36 | 1U7U | E. coli | Coenzyme A biosynthesis bifunctional protein CoaBC | |

| ylbI | BSU15020 | No | 2.7.7.3 | 1O6B | B. subtilis | Pantetheine-phosphate adenylyltransferase | |

| ytaG | BSU29060 | Yes | 2.7.1.24 | 4TTP | Legionella pneumophila | Dephospho-CoA kinase | |

| SAM | |||||||

| metK | BSU30550 | Yes | Yes | 2.5.1.6 | 1FUG | E. coli | S-Adenosylmethionine synthetase |

| Folate | |||||||

| folE | BSU22780 | No | 3.5.4.16 | 4UQF | L. monocytogenes | GTP cyclohydrolase I | |

| phoB | BSU05740 | No | 3.1.3.1 | 3A52 | Shewanella sp. | Alkaline phosphatase A | |

| folB | BSU00780 | No | 4.1.2.25 | 1RRI | S. aureus | Dihydroneopterin aldolase | |

| folK | BSU00790 | No | 2.7.6.3 | 4CYU | S. aureus | 2-Amino-4-hydroxy-6-hydroxymethyl-dihydropteridine diphosphokinase | |

| sul | BSU00770 | No | 2.5.1.15 | 1TWS | B. anthracis | Dihydropteroate synthase | |

| folC | BSU28080 | No | Yes | 6.3.2.17 | 1O5Z | T. maritima | Folyl-polyglutamate synthetase |

| dfrA | BSU21810 | Yes | 1.5.1.3 | 1ZDR | G. stearothermophilus | Dihydrofolate reductase | |

| pabB | BSU00740 | No | 2.6.1.85 | 5CWA | M. tuberculosis | p-Aminobenzoate synthase (subunit A) | |

| pabA | BSU00750 | No | 2.6.1.85 | 1I1Q | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | p-Aminobenzoate synthase (subunit B)/anthranilate synthase (subunit II) | |

| pabC | BSU00760 | No | 4.1.3.38 | 4WHX | Burkholderia pseudomallei | Aminodeoxychorismate lyase | |

| gsaB | BSU08710 | No | 5.4.3.8 | 3L44 | B. anthracis | Formate dehydrogenase | |

| ykkE | BSU13110 | No | 3.5.1.10 | 3W7B | T. thermophilus | Formyltetrahydrofolate deformylase | |

| yoaE | BSU18570 | No | Formate dehydrogenase | ||||

| Heme biosynthesis | |||||||

| hemE | BSU10120 | No | 4.1.1.37 | 2INF | B. subtilis | Glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase | |

| hemH | BSU10130 | No | 1C1H | B. subtilis | Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (uroporphyrinogen III) | ||

| hemY | BSU10140 | No | 1.3.3.4 | 3I6D | B. subtilis | Ferrochelatase | |

| ctaA | BSU14870 | No | Protoporphyrinogen IX oxidase | ||||

| ctaB | BSU14880 | No | Heme A synthase | ||||

| hemL | BSU28120 | No | 5.4.3.8 | 3BS8 | B. subtilis | Heme O synthase (major enzyme) | |

| hemB | BSU28130 | No | 4.2.1.24 | 1W5Q | P. aeruginosa | Glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase | |

| hemD | BSU28140 | No | 4.2.1.75 | Porphobilinogen synthase | |||

| hemC | BSU28150 | No | 2.5.1.61 | 4MLQ | Bacillus megaterium | Uroporphyrinogen III synthase | |

| hemX | BSU28160 | No | Hydroxymethylbilane synthase | ||||

| hemA | BSU28170 | No | 1.2.1.70 | 4N7R | A. thaliana | Glutamyl-tRNA reductase | |

| hemQ | BSU37670 | No | 1T0T | G. stearothermophilus | Heme-binding protein | ||

| Menaquinone | |||||||

| menA | BSU38490 | Yes | Probable 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoate octaprenyltransferase | ||||

| menH | BSU22750 | No | 4OBW | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Menaquinone biosynthesis methyltransferase | ||

| menC | BSU30780 | Yes | 4.2.1.113 | 1WUE | E. faecalis | O-Succinylbenzoate-CoA synthase | |

| menE | BSU30790 | Yes | 6.2.1.26 | 5BUQ | B. subtilis | O-Succinylbenzoate-CoA ligase | |

| menB | BSU30800 | Yes | 4.1.3.36 | 2IEX | G. kaustophilus | Naphthoate synthase | |

| menD | BSU30820 | Yes | 2.2.1.9 | 2X7J | B. subtilis | 2-Succinyl-6-hydroxy-2,4-cyclohexadiene-1-carboxylate synthase/2-oxoglutarate decarboxylase | |

| ytxM | BSU30810 | No | 2XMZ | S. aureus | Similar to prolyl aminopeptidase | ||

| menF | BSU30830 | No | 5.4.4.2 | 3HWO | E. coli | Menaquinone-specific isochorismate synthase | |

| Metals and iron-sulfur clusters | |||||||

| Sodium export | |||||||

| mrpA | BSU31600 | Yes | 4HE8 | T. thermophilus | Na+/H+ antiporter subunit | ||

| mrpB | BSU31610 | Yes | Na+/H+ antiporter subunit | ||||

| mrpC | BSU31620 | Yes | Na+/H+ antiporter subunit | ||||

| mrpD | BSU31630 | Yes | 4HE8 | T. thermophilus | Na+/H+ antiporter subunit | ||

| mrpE | BSU31640 | No | Na+/H+ antiporter subunit | ||||

| mrpF | BSU31650 | Yes | Na+/H+ antiporter subunit | ||||

| mrpG | BSU31660 | No | Na+/H+ antiporter subunit | ||||

| Potassium | |||||||

| ktrD | BSU13500 | No | Yes | 4J7C | B. subtilis | Potassium transporter KtrCD | |

| ktrC | BSU14510 | No | Yes | 4J90 | B. subtilis | Potassium transporter KtrCD | |

| Iron | |||||||

| efeO | BSU38270 | No | 3AT7 | Sphingomonas sp. | Lipoprotein, elemental iron uptake system (binding protein) | ||

| efeU | BSU38280 | No | Elemental iron uptake system (permease) | ||||

| yfmF | BSU07490 | No | 4G1U | Yersinia pestis | Iron/citrate ABC transporter (ATP-binding protein) | ||

| yfmE | BSU07500 | No | 4G1U | Y. pestis | Iron/citrate ABC transporter (permease) | ||

| yfmD | BSU07510 | No | 4G1U | Y. pestis | Iron/citrate ABC transporter (permease) | ||

| yfmC | BSU07520 | No | 3EIW | S. aureus | Iron/citrate ABC transporter (binding protein) | ||

| yhfQ | BSU10330 | No | 3EIW | S. aureus | Iron/citrate ABC transporter (solute-binding protein) | ||

| Magnesium | |||||||

| mgtE | BSU13300 | No | 2YVX | T. thermophilus | Primary magnesium transporter | ||

| mntH | BSU04360 | No | 4WGV | Staphylococcus capitis | Manganese transporter (proton symport) | ||

| Zinc | |||||||

| znuA | BSU02850 | No | 2O1E | B. subtilis | ABC transporter for zinc (binding protein) | ||

| znuC | BSU02860 | No | 4YMS | Caldanaerobacter subterraneus | ABC transporter for zinc (ATP-binding protein) | ||

| znuB | BSU02870 | No | ABC transporter for zinc (permease) | ||||

| Copper | |||||||

| ycnJ | BSU03950 | No | Copper transporter | ||||

| Fe-S cluster | |||||||

| sufB | BSU32670 | Yes | 5AWF | E. coli | Synthesis of Fe-S clusters | ||

| sufU | BSU32680 | Yes | Yes | 1XJS | B. subtilis | Iron-sulfur cluster scaffold protein | |

| sufD | BSU32700 | Yes | 5AWF | E. coli | Synthesis of Fe-S clusters | ||

| sufS | BSU32690 | Yes | Yes | 2.8.1.7 | 1T3I | Synechocystis sp. | Cysteine desulfurase |

| sufC | BSU32710 | Yes | 2D2E | T. thermophilus | ABC transporter (ATP-binding protein) | ||

| fra | BSU05750 | No | 2OC6 | B. subtilis | Frataxin-like protein | ||

| yutI | BSU32220 | No | 1XHJ | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Putative iron-sulfur scaffold protein | ||

| Cell division | |||||||

| Cell wall synthesis | |||||||

| Synthesis of d-glutamate | |||||||

| racE | BSU28390 | Yes | 5.1.1.3 | 1ZUW | B. subtilis | Glutamate racemase | |

| Synthesis of d-Ala-d-Ala | |||||||

| alr | BSU04640 | Yes | 5.1.1.1 | 3ZM5 | S. pneumoniae | Alanine racemase | |

| ddl | BSU04560 | Yes | 6.3.2.4 | 2I80 | S. aureus | d-Alanine-d-alanine ligase | |

| Synthesis of m-diaminopimelate | |||||||

| dapG | BSU16760 | No | 2.7.2.4 | 1SFT | G. stearothermophilus | Aspartokinase I (alpha and beta subunits) | |

| asd | BSU16750 | Yes | 1.2.1.11 | 2GYY | S. pneumoniae | Aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | |

| dapA | BSU16770 | Yes | 4.2.1.52 | 1XKY | B. anthracis | Dihydrodipicolinate synthase | |

| dapB | BSU22490 | Yes | 1.3.1.26 | 5EER | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Dihydrodipicolinate reductase (NADPH) | |

| ykuQ | BSU14180 | Yes | 2.3.1.89 | 3R8Y | B. anthracis | Similar to tetrahydrodipicolinate succinylase | |

| patA | BSU14000 | Yes | 1GDE | P. horikoshii | Aminotransferase | ||

| dapI | BSU14190 | Yes | 3.5.1.47 | 1YSJ | B. subtilis | N-Acetyl-diaminopimelate deacetylase | |

| dapF | BSU32170 | Yes | 5.1.1.7 | 2OTN | B. anthracis | Diaminopimelate epimerase | |

| Isoprenoid biosynthesis | |||||||

| dxs | BSU24270 | Yes | 2.2.1.7 | 2O1S | E. coli | 1-Deoxyxylulose-5-phosphate synthase | |

| ispC | BSU16550 | Yes | 1.1.1.267 | 1R0K | Zymomonas mobilis | 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase | |

| ispD | BSU00900 | Yes | 2.7.7.60 | 2YC3 | A. thaliana | 2-C-Methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase | |

| ispE | BSU00460 | Yes | 2.7.1.148 | 3PYD | M. tuberculosis | 4-Diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-d-erythritol kinase | |

| ispF | BSU00910 | Yes | 4.6.1.12 | 3GHZ | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | 2-C-Methyl-d-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase | |

| ispG | BSU25070 | Yes | 3NOY | A. aeolicus | Similar to peptidoglycan acetylation, 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl-4-diphosphate synthase | ||

| ispH | BSU25160 | Yes | 4N7B | Plasmodium falciparum | (E)-4-Hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase | ||

| fni | BSU22870 | No | 5.3.3.2 | 1P0K | B. subtilis | Isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase | |

| Undecaprenyl phosphate biosynthesis | |||||||

| yqiD | BSU24280 | No | 2.5.1.10 | 1RTR | S. aureus | Geranyltransferase | |

| uppS | BSU16530 | Yes | 2.5.1.31 | 1F75 | Micrococcus luteus | Probable undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthetase | |

| bcrC | BSU36530 | No | Undecaprenyl pyrophosphate phosphatase | ||||

| hepT | BSU22740 | Yes | 2.5.1.30 | 3AQB | M. luteus | Heptaprenyl diphosphate synthase component II | |

| hepS | BSU22760 | Yes | 2.5.1.30 | Heptaprenyl diphosphate synthase component I | |||

| Peptidoglycan biosynthesis | |||||||

| glmS | BSU01780 | Yes | 2.6.1.16 | 4AMV | E. coli | Glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate transaminase | |

| glmM | BSU01770 | Yes | 5.4.2.10 | 3PDK | B. anthracis | Phosphoglucosamine mutase | |

| gcaD | BSU00500 | Yes | 2.7.7.23 | 4AAW | S. pneumoniae | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase | |

| murAA | BSU36760 | Yes | 2.5.1.7 | 3SG1 | B. anthracis | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase | |

| murB | BSU15230 | Yes | 1.1.1.158 | 4PYT | Unidentified | UDP-N-acetylenolpyruvoylglucosamine reductase | |

| murC | BSU29790 | Yes | 6.3.2.8 | 1GQQ | H. influenzae | UDP-N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine synthetase | |

| murD | BSU15200 | Yes | 6.3.2.9 | 3LK7 | Streptococcus agalactiae | UDP-N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanyl-d-glutamate synthetase | |

| murE | BSU15180 | Yes | 6.3.2.13 | 4C13 | S. aureus | UDP-N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanyl-d-glutamyl-meso-2,6-diaminopimelate synthetase | |

| murF | BSU04570 | Yes | 6.3.2.10 | 1GG4 | E. coli | UDP-N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanyl-d-glutamyl-meso-2,6-diaminopimeloyl-d-alanyl-d-alanine synthetase | |

| mraY | BSU15190 | Yes | 2.7.8.13 | 4J72 | A. aeolicus | Phospho-N-acetylmuramoyl-pentapeptide transferase (meso-2,6-diaminopimelate) | |

| murG | BSU15220 | Yes | 2.4.1.227 | 1F0K | E. coli | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine-N-acetylmuramyl-(pentapeptide)pyrophosphoryl-undecaprenol N-acetylglucosamine transferase | |

| murJ | BSU30050 | No | Lipid II flippase | ||||

| Peptidoglycan polymerization | |||||||

| ponA | BSU22320 | No | 3DWK | S. aureus | Penicillin-binding protein 1A/1B | ||

| PG cross-links, cell separation | |||||||

| pbpB | BSU15160 | Yes | 1RP5 | S. pneumoniae | Penicillin-binding protein 2B | ||

| pbpA | BSU25000 | No | 3VSK | S. aureus | Penicillin-binding protein 2A | ||

| lytE | BSU09420 | No | 4XCM | T. thermophilus | Cell wall hydrolase (major autolysin) for cell elongation and separation | ||

| lytF | BSU09370 | No | 4XCM | T. thermophilus | Gamma-d-glutamate-meso-diaminopimelate muropeptidase (major autolysin) | ||

| Wall teichoic acid | |||||||

| tagO | BSU35530 | Yes | 4J72 | A. aeolicus | Undecaprenyl phosphate-GlcNAc-1-phosphate transferase | ||

| mnaA | BSU35660 | Yes | 5.1.3.14 | 4FKZ | B. subtilis | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase | |

| tagA | BSU35750 | Yes | 2.4.1.187 | UDP-N-acetyl-d-mannosamine transferase | |||

| tagB | BSU35760 | Yes | 3L7I | S. epidermidis | Putative CDP-glycerol:glycerol phosphate glycerophosphotransferase | ||

| tagD | BSU35740 | Yes | 2.7.7.39 | 1COZ | B. subtilis | Glycerol-3-phosphate cytidylyltransferase | |

| tagF | BSU35720 | Yes | 2.7.8.12 | 3L7I | S. epidermidis | CDP-glycerol:polyglycerol phosphate glycerophosphotransferase | |

| tagH | BSU35700 | Yes | 3.6.3.40 | ABC transporter for teichoic acid translocation (ATP-binding protein) | |||

| tagG | BSU35710 | Yes | ABC transporter for teichoic acid translocation (permease) | ||||

| tagU | BSU35650 | No | 3OWQ | L. innocua | Phosphotransferase, attachment of anionic polymers to peptidoglycan | ||

| Lipoteichoic acid | |||||||

| dgkB | BSU06720 | Yes | 2QV7 | S. aureus | Diacylglycerol kinase | ||

| pgcA | BSU09310 | No | Yes | 5.4.2.2 | 2Z0F | T. thermophilus | Alpha-phosphoglucomutase |

| gtaB | BSU35670 | No | Yes | 2.7.7.9 | 2UX8 | Sphingomonas elodea | UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase |

| ltaS | BSU07710 | No | 2W8D | B. subtilis | Lipoteichoic acid synthase | ||

| ugtP | BSU21920 | No | UDP-glucose diacylglycerol glucosyltransferase | ||||

| Coordination | |||||||

| Divisome | |||||||

| divIC | BSU00620 | Yes | Cell division initiation protein (septum formation) | ||||

| ftsL | BSU15150 | Yes | Cell division protein (septum formation) | ||||

| divIB | BSU15240 | Yes | 1YR1 | G. stearothermophilus | Cell division initiation protein (septum formation) | ||

| ftsZ | BSU15290 | Yes | 2VAM | B. subtilis | Cell division initiation protein (septum formation) | ||

| ftsW | BSU14850 | Yes | Cell division protein | ||||

| ezrA | BSU29610 | No | 4UXV | B. subtilis | Negative regulator of FtsZ ring formation | ||

| sepF | BSU15390 | No | 3ZIH | B. subtilis | Part of the divisome | ||

| gpsB | BSU22180 | No | 4UG3 | B. subtilis | Removal of PBP1 from the cell pole after completion of cell pole maturation | ||

| yvcK | BSU34760 | No | 2HZB | B. halodurans | Correct localization of PBP1, essential for growth under gluconeogenic conditions | ||

| yvcL | BSU34750 | No | Yes | 3HYI | T. maritima | Involved in Z-ring assembly | |

| Division site selection | |||||||

| divIVA | BSU15420 | No | 2WUJ | B. subtilis | Cell division initiation protein (septum placement) | ||

| minC | BSU28000 | No | 2M4I | B. subtilis | Cell division inhibitor (septum placement) | ||

| minD | BSU27990 | No | 4V03 | A. aeolicus | Cell division inhibitor (septum placement) | ||

| noc | BSU40990 | No | 1VZ0 | T. thermophilus | DNA-binding protein, spatial regulator of cell division to protect the nucleoid, coordination of chromosome segregation and cell division | ||

| minJ | BSU35220 | No | Topological determinant of cell division | ||||

| Elongasome | |||||||

| mreD | BSU28010 | Yes | Cell shape-determining protein, associated with the MreB cytoskeleton | ||||

| mreC | BSU28020 | Yes | 2J5U | L. monocytogenes | Cell shape-determining protein, associated with the MreB cytoskeleton | ||

| mreB | BSU28030 | Yes | 4CZE | Caulobacter vibrioides | Cell shape-determining protein | ||

| rodA | BSU38120 | Yes | Control of cell shape and elongation | ||||

| mreBH | BSU14470 | No | 1JCF | T. maritima | Cell shape-determining protein | ||

| rodZ | BSU16910 | Maybe | Required for cell shape determination | ||||

| Coordination of cell division and DNA replication | |||||||

| walJ | BSU40370 | No | 4P62 | P. aeruginosa | Coordination of cell division and DNA replication | ||

| Signaling | |||||||

| walK | BSU40400 | Yes | 4I5S | S. mutans | Two-component sensor kinase | ||

| walR | BSU40410 | Yes | 2ZWM | B. subtilis | Two-component response regulator | ||

| cdaA | BSU01750 | No | 2.7.7.85 | 4RV7 | L. monocytogenes | Diadenylate cyclase | |

| gdpP | BSU40510 | No | c-di-AMP-specific phosphodiesterase | ||||

| Integrity of the cell | |||||||

| Protection | |||||||

| ytbE | BSU29050 | Yes | 3B3D | B. subtilis | Putative aldo/keto reductase | ||

| katA | BSU08820 | No | 1SI8 | E. faecalis | Vegetative catalase 1 | ||

| sodA | BSU25020 | No | 2RCV | B. subtilis | Superoxide dismutase | ||

| ahpC | BSU40090 | No | 1WE0 | Amphibacillus xylanus | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (small subunit) | ||

| ahpF | BSU40100 | No | 4O5Q | E. coli | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (large subunit)/NADH dehydrogenase | ||

| trxA | BSU28500 | Yes | Yes | 2GZY | B. subtilis | Antioxidative action by facilitating the reduction of other proteins by cysteine thiol-disulfide exchange | |

| yumC | BSU32110 | Yes | 1.18.1.2 | 3LZW | B. subtilis | Ferredoxin-NAD(P)+ oxidoreductase | |

| trxB | BSU34790 | Yes | Yes | 1.8.1.9 | 4GCM | S. aureus | Thioredoxin reductase (NADPH) |

| Repair/genome integrity | |||||||

| hlpB | BSU10660 | Yes | HNH nuclease-like protein, rescues AddA recombination intermediates | ||||

| mutY | BSU08630 | No | 5DPK | G. stearothermophilus | A/G-specific adenine glycosylase | ||

| polY1 | BSU23870 | No | 2.7.7.7 | 4IRC | E. coli | Translesion synthesis DNA polymerase Y1 | |

| mutM | BSU29080 | No | 3.2.2.23 | 1L1T | G. stearothermophilus | Formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosidase | |

| mfd | BSU00550 | No | 2EYQ | E. coli | Transcription repair-coupling factor | ||

| recD2 | BSU27480 | No | 3E1S | Deinococcus radiodurans | 5′–3′ DNA helicase replication fork progression | ||

| rnhB | BSU16060 | No | 3O3G | T. maritima | RNase HII, endoribonuclease | ||

| recA | BSU16940 | No | 1UBC | Mycobacterium smegmatis | Homologous recombination and DNA repair | ||

| Other/unknown | |||||||

| ppaC | BSU40550 | Yes | 3.6.1.1 | 1WPM | B. subtilis | Inorganic pyrophosphatase | |

| ylaN | BSU14840 | Yes | 2ODM | S. aureus | Unknown | ||

| yitI | BSU11000 | No | 2JDC | Bacillus licheniformis | Unknown | ||

| yitW | BSU11160 | No | 3LNO | B. anthracis | Unknown | ||

| yqhY | BSU24330 | No | Unknown | ||||

| ykwC | BSU13960 | No | 3WS7 | Pyrobaculum calidifontis | Putative beta-hydroxy acid dehydrogenase | ||

| ylbN | BSU15070 | No | Unknown | ||||

| ypfD | BSU22880 | No | 4Q7J | E. coli | Similar to ribosomal protein S1 | ||

| yugI | BSU31390 | No | 2K4K | B. subtilis | Similar to polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase | ||

| floT | BSU31010 | No | Similar to flotillin 1, orchestration of physiological processes in lipid microdomains | ||||

| yyaF | BSU40920 | No | Yes | 1JAL | H. influenzae | GTP-binding protein/GTPase |

The BSU number is the locus tag in the context of the B. subtilis 168 genome (GenBank accession no. NC_000964).

The essentiality of a gene refers to wild-type B. subtilis 168. By definition, genes that cannot be deleted as individual genes under defined optimal growth conditions (Luria-Bertani broth with glucose at 37°C) are regarded as being essential.

Each gene of the MiniBacillus gene set was tested for the presence of a homolog in Mycoplasma mycoides JCVI-syn3.0 by using a BLASTP analysis.

The organism refers to the PDB accession number.

PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate; TPP, thiamine PPi; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; PTS, phosphotransferase system; PBP1, penicillin-binding protein 1.

TABLE 3.

rRNAs and tRNAs

DNA Replication and Chromosome Segregation/Maintenance