Abstract

Analyses from the National Comorbidity Study Replication provide the first nationally-representative estimates of the co-occurrence of pathological anger traits and possessing or carrying a gun among adults with and without certain mental disorders and demographic characteristics. The study found that a large number of individuals in the United States have anger traits and also possess firearms at home (10.4%) or carry guns outside the home (1.6%). These data document associations of numerous common mental disorders and combinations of anger traits with gun access. Because only a small proportion of persons with this risky combination have ever been hospitalized for a mental health problem, most will not be subject to existing mental-health-related legal restrictions on firearms due to involuntary commitment. Excluding a large proportion of the general population from gun possession is also not likely to be feasible. Behavioral risk-based approaches to firearms restriction, such as expanding the definition of gun-prohibited persons to include those with violent misdemeanor convictions and multiple DUI convictions, could be a more effective public health policy to prevent gun violence in the population.

Keywords: Violence, mental illness, gun possession

INTRODUCTION

Intentional acts of interpersonal violence with guns killed 11,622 people and injured an additional 59,077 in the United States in 2012 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Meanwhile, public response to mass shootings has animated a national discussion of gun violence linked to mental illness in particular, ensnaring mental health policy in the politics of gun control (Edwards, 2014). In a nation with a constitutionally-protected right to own firearms (District of Columbia v. Heller, 2008; McDonald v. City of Chicago, 2010) and more than 310 million firearms estimated to be in private hands (Krouse, 2012), finding effective and legitimate ways to keep dangerous people from accessing firearms is a formidable task (McGinty et al.,, 2014; Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy, 2013a; Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy, 2013b).

Gun violence and mental illness are complex but different public health problems that intersect only on their edges. Viewing them together through the lens of mass-casualty shootings can distort our perspectives on both of them as well as confound policy solutions and create strange and ambivalent bedfellows in the advocacy space (Swanson, McGinty, Fazel, Mays, 2014). On one hand, gun rights advocates have been eager to link gun violence to serious mental illness (The Economist, 2013)—an idea that resonates powerfully with public opinion and is fueled by ubiquitous media portrayals—and to suggest that controlling people with serious mental illness instead of controlling firearms is the key policy answer to reducing gun violence in America. On the other hand, mental health consumer advocates have been drawn into an overdue discussion of how best to fix a dysfunctional mental healthcare system (Mechanic, 2014), but for the wrong reasons and at the peril of unintended adverse consequences; “fixing mental health” primarily as a violence-prevention strategy may exacerbate and exploit the public’s discriminatory fear of people with psychiatric disorders, the large majority of whom are never violent.

The experts who study both mental illness and firearms injury from a population health perspective have weighed in on the side of the mental health advocates (McGinty, Webster, Barry, 2014), citing evidence that only a very small proportion of the overall problem of interpersonal violence is attributable to serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression (Appelbaum, 2013; Swanson, 2013). At the same time, mental health experts have been at pains to qualify their myth-busting “gun-violence-is-not-about-mental-illness” argument in light of four important realities: first, the contribution of mental illness to gun-related suicide (Cavanagh et al., 2003; Li et al., 2011); second, the inherently aberrant nature of violent acts; third, the real, albeit modest, association between mental disorder and violence in most epidemiological studies; and fourth, the existence of meaningful associations of broadly-defined psychopathology with social-environmental and developmental risk factors for harmful behaviors (Desmarais et al., 2013; Swanson et al., 2002.)

Pathological impulsive anger, as a personality trait, conveys some inherent risk of aggressive or violent behavior (Yu et al., 2012) which can become lethal when combined with access to firearms. There is also evidence that anger can mediate the relationship between symptoms of mental illness and violent behavior (Coid, et al., 2013). But what proportion of the angry people in the population who own or carry guns has a diagnosable mental illness? And what proportion of the latter has a history of involuntary hospitalization for serious mental illness, which would disqualify them from owning firearms? Answers to these questions are important to get straight if we are to evaluate the implications of contending policy recommendations. Data on these questions are presented here based on of new analyses of nationally representative data from the National Comorbidity Study Replication (NCS-R; Kessler et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 2005a). We present the first nationally representative estimates of the co-occurrence of anger traits and possessing or carrying a gun among people with and without a wide range of diagnosable mental disorders. We present descriptive data on significant demographic and diagnostic correlates of the conjunction between gun access (possessing guns at home or carrying guns outside the home) and trait anger (having angry outbursts, become angry and breaking or smashing things, losing one’s temper and getting into physical fights.) While we do not present data on completed acts of interpersonal violence, our measure has some face validity as an indicator of inherent risk of violence, and thus our study complements existing literature on violent behavior. We close by placing our findings in context and discussing policy implications.

METHODS

Sample

The NCS-R is a nationally representative household survey of respondents 18 years and older in the contiguous United States (Kessler et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 2005a). Face-to-face interviews were carried out with 9,282 respondents between February 5, 2001, and April 7, 2003. Part I included a core diagnostic assessment and a service use questionnaire administered to all respondents. Part II (n = 5,962) assessed risk factors, correlates and additional disorders, and was administered to all Part I respondents with lifetime disorders plus a probability subsample of other respondents. Because questions about gun ownership were asked only in Part II, the present analyses are limited to the Part II sample. This sample was appropriately weighted to adjust for the under-sampling of Part I respondents without any disorder. The overall response rate was 70.9%. The 309 respondents in the Part II sample who had to carry a gun as part of their work were excluded from the analysis. The remaining 5,653 respondents are the focus of the analysis. NCS-R recruitment, consent, and field procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan.

Measures

Gun possession and carrying

Part II NCS-R respondents were asked “How many guns that are in working condition do you have in your house, including handguns, rifles, and shotguns?” (The question is referred to below as gun possession.) They were also asked “Not counting times you were shooting targets, how many days during the past 30 days did you carry a gun outside your house?” (This question is referred to below as gun carrying.) As already noted, respondents were also asked if they had a job that required them to carry a gun, in which case they were excluded from the analyses reported in this paper.

Trait anger

As part of the NCS-R assessment of personality disorders, three questions were asked about trait anger. The introduction to the section told respondents that the interviewer was “going to read a series of statements that people use to describe themselves” and that the respondent should answer “true” or “false” for each statement. The three statements regarding trait anger were: “I have tantrums or angry outbursts”; “Sometimes I get so angry I break or smash things”; and “I lose my temper and get into physical fights.”

Mental disorders

DSM-IV mental disorders were assessed with Version 3.0 of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Kessler & Üstün, 2004), a fully-structured lay interview that generates diagnoses according to the definitions and criteria of both the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (World Health Organization, 1992) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). DSM-IV criteria are used in the current report. A total of 21 disorders are considered here. Based on the results of previously-reported factor analyses (Kessler et al., 2005c), we organize these disorders into the categories of Axis I internalizing disorders (major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, separation anxiety disorder), externalizing disorders (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, eating disorders [either anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge-eating disorder], intermittent explosive disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, pathological gambling disorder, alcohol or illicit drug abuse with or without dependence, alcohol or drug dependence with abuse), other severe Axis I disorders (bipolar I or II disorder, non-affective psychosis [NAP; either schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, or psychosis not otherwise specified), and Axis II (personality) disorders. The personality disorders were grouped into Clusters A (odd or eccentric), B (dramatic, emotional, or erratic), and C (anxious or fearful).

Given that questions about gun possession/carrying were asked about the present, we focused on mental disorders in the 12 months before interview rather than lifetime, but there were two exceptions. First, we considered lifetime rather than 12-month NAP in light of the fact that the number of 12-month cases of NAP was too small for analysis and none of these 12-month cases owned a gun. Second, we considered five-year rather than 12-month personality disorders because personality disorders were assessed only over a five-year recall period. As described elsewhere, blinded clinical reappraisal interviews using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First et al., 2002) with a probability subsample of NCS-R respondents found generally good concordance between DSM-IV diagnoses of Axis I disorders based on the CIDI and on the SCID (Kessler et al., 2005a; Kessler et al., 2005b). Personality disorders, in comparison, were based on screening questions from the International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE; Loranger et al., 1994). Diagnoses were derived from these screening questions by calibrating with independent clinical diagnoses based on blinded clinical appraisal interviews with the full IPDE. These calibrated diagnoses had good concordance with blinded clinical diagnoses (Lenzweger et al., 2007.)

Socio-demographics

Socio-demographic variables considered here include age (18–34, 35–49, 50–64, 65+), sex, race-ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other), family income in relation to the federal poverty level (Proctor & Dalaker, 2001) (low [≤1.5 times the poverty line], low average [>1.5–3 times the poverty line], high average [>3–6 times the poverty line], high [≥6 times the poverty line]), marital status (married/cohabitating, separated/widowed/divorced, never married), Census region of the country (Northeast, South, Midwest, West), and urbanicity (central cities of Metropolitan Statistical Areas [MSAs] with populations greater than 2 million, central cities of smaller MSAs, suburbs of central cities in both large and small MSAs, contiguous areas to suburbs of MSAs [of any size], and all other areas in the country).

Analysis methods

As noted above in the description of the sample, the NCS-R data were weighted to adjust for differences in selection probabilities, differential non-response, and residual differences between the sample and the US population on socio-demographic variables. An additional weight was used in the Part II sample to adjust for the over-sampling of Part I respondents (Kessler et al., 2004). All results reported here are based on these weighted data. Cross-tabulations were used to examine the distribution and associations of gun access (number of guns in the home) with gun possession, trait anger, and the conjunction of anger and possession. Logistic regression analysis was then used to estimate associations of types and number of mental disorders with six outcomes: any gun access, gun possession, the conjunction of access with any trait anger (i.e., both having access to a gun and responding positively to any of the three trait anger questions) and with fighting (i.e., both having access to a gun and reporting “I lose my temper and get into physical fights”), and the conjunction of possession with any trait anger and with fighting. Logistic regression coefficients and their standard errors were exponentiated for ease of interpretation and are reported as odds-ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Population attributable risk proportions (PARP) were calculated to describe the overall strength of associations between mental disorders and each of the six outcomes. PARP can be interpreted as the proportion of respondents with the observed outcomes that would not have had those outcomes in the absence of the predictors if the associations described in the logistic regression equations between predictors and outcomes reflect causal effects of the predictor (Rothman and Green, 1988). Although it is inappropriate to infer causality from the NCS-R data, the calculation of PARP is nonetheless useful in providing a sense of the magnitudes of the multivariate associations of mental disorders with each outcome.

Standard errors of prevalence estimates and logistic regression coefficients were calculated using the Taylor series method implemented in the SUDAAN software package (Research Triangle Institute, 2002) to adjust for the clustering and weighting of the NCS-R data. Multivariate significance tests were conducted using Wald χ2 tests based on coefficient variance–covariance matrices adjusted for design effects using the Taylor series method. Statistical significance was evaluated using two-sided design-based tests and the p<0.05 level of significance.

RESULTS

Prevalence and associations of gun possession with gun carrying and anger

More than one-third (36.5%) of NCS-R respondents reported having one or more guns in working condition in their homes, with 10.7% having one gun, 6.6% two, 9.3% three to five, 4.6% six to ten, and 5.2% more than ten guns (Table 1). The proportion of respondents in the total sample who reported carrying a gun outside the house at some time in the past month was 4.4%. Of those who had carried a gun outside the house, about two thirds reported carrying every day (not shown in Table 1.) The proportion who reported carrying a gun outside the home was significantly higher among those with than without guns in the home (10.8% vs. 0.7%, χ21 = 94.2, p < .001) and was significantly related to number of guns among those having any (from a low of 7.3% among those with one gun to a high of 22.2% among those with more than ten guns, χ24 = 22.8, p = <.001).

Table 1.

Distribution of number of guns in working condition in the households of respondents and the associations of number of guns with carrying a gun, anger-violence, and the conjunction of carrying a gun and anger-violence in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) (n = 5,653)1

| Trait anger indicators | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Carries gun | Has tantrums or angry outbursts |

Breaks/smashes things in anger |

Loses temper and has physical fights |

Any of three anger indicators |

Carries gun and any of three anger indicators |

||||||||

| Number of guns |

% | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) |

| 0 | 63.5 | −1.5 | 0.7 | −0.2 | 19.2 | −1 | 12.6 | −0.5 | 6.1 | −0.6 | 25.4 | −1.2 | 0.2 | −0.1 |

| 1 | 10.7 | −0.6 | 7.3 | −1.1 | 19.1 | −2 | 8.7 | −1.3 | 3.7 | −0.8 | 21.9 | −2.1 | 1.8 | −0.7 |

| 2 | 6.6 | −0.4 | 8.8 | −1.9 | 17.2 | −2 | 11.1 | −1.8 | 5.9 | −1.6 | 23.4 | −2.6 | 2.9 | −1 |

| 3 to 5 | 9.3 | −0.6 | 8.4 | −1.3 | 20.5 | −2.4 | 11.2 | −1.4 | 5.7 | −1.4 | 27 | −2.3 | 2.5 | −0.7 |

| 6 to 10 | 4.6 | −0.4 | 14.2 | −2.5 | 19.8 | −3 | 8.5 | −1.5 | 6.8 | −1.6 | 25.2 | −3.2 | 7.8 | −1.7 |

| 11+ | 5.2 | −0.3 | 22.2 | −4.4 | 18.6 | −3.2 | 10.1 | −2 | 9.1 | −1.9 | 24.6 | −3.6 | 7.3 | −2.9 |

| Any guns |

36.5 | −1.5 | 10.8 | −0.8 | 19.1 | −0.9 | 10 | −0.7 | 5.8 | −0.5 | 24.3 | −1 | 3.7 | −0.6 |

| Total | 100 | 4.4 | −0.4 | 19.1 | −0.7 | 11.6 | −0.4 | 6 | −0.5 | 25 | −0.8 | 1.5 | −0.3 | |

| χ25 2 | 110.5* | 1.9 | 17.1* | 14.6* | 3.8 | 32.6* | ||||||||

| χ24 3 | 22.8* | 1.8 | 13.4* | 4.8 | 3.3 | 10.7* | ||||||||

| χ21 4 | 94.2* | 0 | 0.3 | 8.1* | 0.4 | 23.8* | ||||||||

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test.

Based on the weighted Part II NCS-R sample excluding the 39 respondents who are employed in a protective services occupation that requires carrying a gun

Chi-square test for difference between respondents with different numbers of guns in the home, including those without guns (5 DF).

Chi-square test for significant difference between number of guns among those with any guns in the home (4 DF).

Chi-square test for significant difference between those with and without guns in the home (1 DF))

The proportions of respondents who reported having tantrums or anger outbursts (19.1% in the total sample) or at least one of the anger items (25.0% in the total sample) were not significantly related either to having guns in the home (χ21 = 0.0–0.4, p = 0.51–0.98) or to number of guns among those having any (χ24 = 1.8–3.3, p = 0.52–0.77). The proportion of respondents who reported breaking or smashing things in anger (11.6% in the total sample), in comparison, was significantly lower among respondents with than without guns in the home (10.0% vs. 12.6%, χ21 = 8.1, p = .007), although not significantly related to number of guns among those having any (χ21 = 4.8, p = 0.32). The proportion of respondents who reported losing their temper and fighting (6.0% in the total sample) was not significantly related to having guns in the home (χ21 = 0.3, p = 0.61), but was positively and significantly associated with number of guns among those who had any guns (χ21 = 13.4, p = 0.018).

The proportions of respondents who reported both carrying a gun and either having at least one of the anger items (1.5% in the total sample) or fighting (0.5% in the total sample) were significantly higher among those with than without guns in the home (3.7% vs. 0.2% for any anger, χ21 = 23.8, p = <.001; 1.4% vs. 0.0% for fighting, χ21 = 13.2, p = 0.001). 0.7%, χ21 = 94.2, p < .001) and higher among respondents with six or more than fewer guns (7.3–7.8% vs. 1.8–2.9% who both carried a gun and had anger, χ21 = 2.8, p = 0.10; 2.9–3.2% vs. 0.4–1.7% who both carried a gun and fought, χ21 = 5.9, p = 0.019).

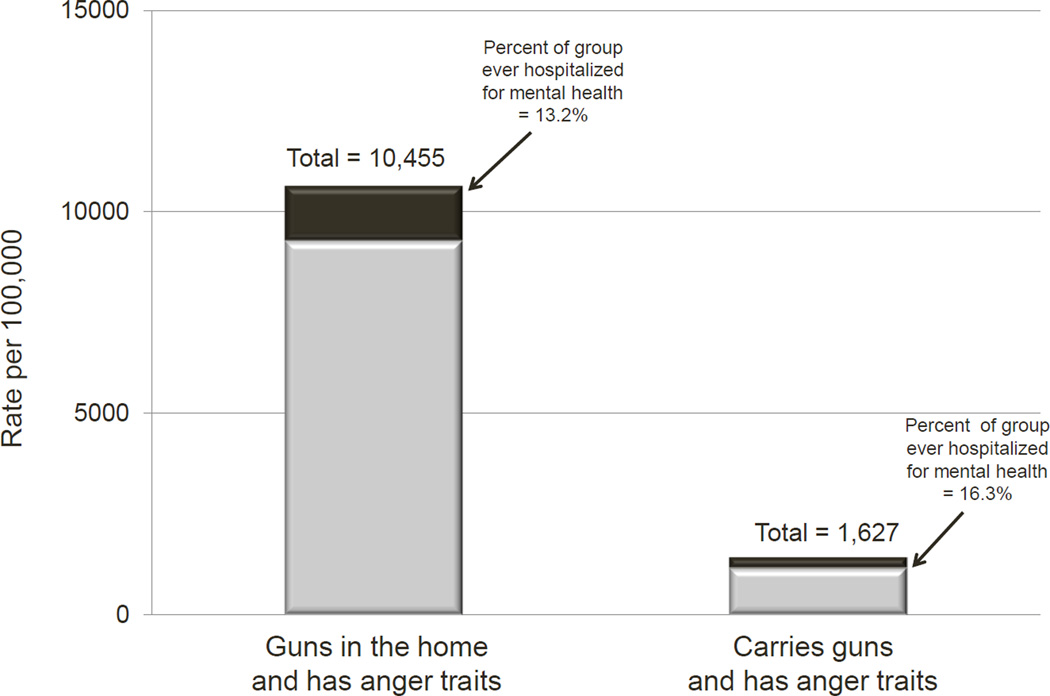

Extrapolating from these nationally-representative survey findings, an estimated 10,455 individuals per 100,000 in the population have guns at home and have one of the pathological anger traits assessed in the NCS-R, while an estimated 1,627 per 100,000 carry guns and have one or more of these anger traits.

Socio-demographic correlates of gun access/carrying and anger

Men were significantly more likely than women to report all outcomes (guns in home, carries gun, guns in home/has anger traits, and carries gun/has anger traits), with ORs in the range 1.9 (gun possession) to 10.4 (for the conjunction of carrying a gun and fighting), as shown in Table 2. Age was inversely related to the conjunction of guns at home and anger, with ORs of 1.9–2.8 for respondents under age 60 compared to those 60+, but not to any other outcome (χ23 = 0.8–3.9, p = 0.27–0.83). ORs of gun possession were significantly lower among Hispanics (0.4) and Others (0.4) than Non-Hispanic Whites and Non-Hispanic Blacks, but race-ethnicity was not significantly related to any other outcome (χ23 = 0.6–5.0, p = 0.17–0.90). Lower family income was associated with lower likelihood of gun possession (ORs of 0.6–0.8 among respondents with low/low-average vs. high income), but was not associated with other outcomes (χ23 = 0.8–6.9, p = 0.09–0.84). Never married and previously married respondents were significantly less likely than the married to possess guns and to have the conjunction of possession and anger traits (ORs = 0.4–0.6).

Table 2.

Associations of socio-demographic variables with conjunctions of gun ownership, carrying a gun, and indicators of trait anger in the weighted Part II NCS-R sample (n = 5,653)1

| Guns in home | Carries gun | Guns in home and has anger traits |

Carries gun and has anger traits |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.9* | 4.8* | 2.1* | 4.5* |

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| χ21 | 71.0* | 121.6* | 33.4* | 20.4* |

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 | 1 | 1.3 | 2.8* | 1.9 |

| 30–44 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.6* | 1.9 |

| 45–59 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.9* | 1.2 |

| 60+ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| χ23 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 44.8* | 3.9 |

| Race-ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.4* | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.2 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.3 |

| Other | 0.4* | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| χ23 | 34.9* | 0.6 | 5 | 0.6 |

| Region | ||||

| Midwest | 2.3* | 1.1 | 1.5 | 0.6 |

| South | 2.3* | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1 |

| West | 2.0* | 1.5 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Northeast | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| χ23 | 10.0* | 11.4* | 5 | 1.6 |

| Urbanicity | ||||

| Central Cities, pop. < 2,000,000 | 1.8* | 2.1 | 1.8* | 0.8 |

| Suburbs of Central Cities, pop. > 2,000,000 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.9* | 1.2 |

| Suburbs of Central Cities, pop. < 2,000,000 | 2.3* | 1.8* | 2.6* | 2.8* |

| Adjacent area outside w/in 50 miles of Central City |

4.6* | 2.9* | 3.0* | 2.7 |

| Outlying Area | 5.4* | 5.7* | 4.9* | 7.8* |

| Central Cities with population > 2,000,000 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| χ25 | 141.8* | 59.6* | 42.8* | 43.8* |

| Income | ||||

| Low | 0.6* | 0.6* | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| Low-average | 0.8* | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| High-average | 0.9 | 0.5* | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| High | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| χ21 | 14.9* | 6.5 | 0.8 | 1.7 |

| Married/Cohabitating | ||||

| Previously married | 0.4* | 0.9 | 0.6* | 1.1 |

| Never Married | 0.4* | 0.7 | 0.5* | 0.9 |

| Married | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| χ21 | 73.9* | 1.9 | 14.5* | 0.3 |

Age groups 18–44, 45–59 and 60+ were used to predict carrying-fighting outcome. Chi-square test of age predicting carrying-fighting has 2 degrees of freedom.

Suburbs of central cities with population greater and less than 2,000,000, as well as adjacent and outlying areas of central cities were combined to predict this outcome. Chi-square test of urbanicity predicting carrying-fighting has 3 degrees of freedom.

Significant regional differences exist in gun ownership, with much higher odds in the Midwest, South, and West (2.0–2.3) than the Northeast. Urbanicity was inversely related to all the outcomes other than the conjunction of carrying/fighting (χ25 = 28.3–141.8, p< .001), with outlying areas having odds 3.8–7.8 as high as central cities of large metropolitan areas. The same generally inverse monotonic relationship with urbanicity can be seen for carrying/fighting as the other outcomes and this relationship becomes statistically significant when the six urbanicity categories are collapsed to three (i.e., combining the largest with smaller central cities, the suburbs of largest with smaller central cities, and adjacent with outlying areas, χ22 = 4.1, p = .043).

Associations of DSM-IV/CIDI mental disorders with gun possession/carrying and anger

Inspection of bivariate associations (odds ratios) between each DSM-IV/CIDI disorder considered here and the outcomes controlling for socio-demographic characteristics shows that a wide range of mental disorders were associated with these outcomes. Included here were depression, bipolar and anxiety disorders, PTSD, intermittent explosive disorder, pathological gambling, eating disorders, alcohol and illicit drug use disorders, and a range of personality disorders; significant ORs were in the range 1.8–9.8.

We also estimated three alternative versions of multivariate models that included all 21 mental disorders along with the socio-demographic controls. The first model included a separate predictor variable for each of the 21 disorders. The second model included counts for the number of each respondent’s internalizing and externalizing disorders. The third model included predictors for both type and number of disorders. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), two commonly-used criteria for evaluating comparative model fit (Burnham and Anderson, 2002) were used to compare the three models. Both number and type of disorders were significantly associated with the anger/gun-carry index, controlling for demographic characteristics. However, schizophrenia (nonaffective psychosis) and bipolar disorder did not show net significant associations with anger/carry when all other covariates were included in the models, although it is noteworthy that these are relatively rare disorders and the study had too few cases of them to provide an adequately powered analysis.

Population attributable risk proportions (PARP) associated with DSM-IV/CIDI mental disorders controlling for socio-demographic variables were 34.5% for the conjunction of anger traits with having guns in the home and 55.7% for the conjunction of anger traits with carrying guns. In other words, if the regression coefficients represented causal effects of mental disorders and all these disorders could somehow be “cured,” we would expect that the population prevalence of anger traits in conjunction with guns in the home, and with carrying guns, would be reduced by about 35% and 56%, respectively.

Despite evidence of considerable psychopathology in many of the respondents with anger traits combined with gun access, only a very small proportion (13–16%) of these individuals were ever voluntarily or involuntarily hospitalized for a mental health problem, as shown in Figure 1. It is only this small minority of cases that could have had a potentially gun-disqualifying involuntary commitment.

Figure 1.

Estimated number per 100,000 population with gun violence risk indicator and percent ever hospitalized for a mental health problem

CONCLUSION

This nationally representative survey found that a large number of individuals in the United States have a combination of pathological anger traits and access to firearms. An estimated 10,455 per 100,000 population have guns at home in conjunction with anger traits, while an estimated 1,627 per 100,000 carry guns and have anger traits. The study also found a significant three-way association among owning multiple guns, carrying a gun, and having pathological anger traits. People owning 6 or more guns were about 4 times as likely to be in the high-risk anger/carry group as those owning only 1 gun (about 8% vs. 2% prevalence.)

Persons with anger traits who had access to guns at home were more likely to be male, younger, married, and to live in outlying areas around metropolitan centers rather than in central cities. Persons with anger traits who carried guns were significantly more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for a wide range of mental disorders, including depression, bipolar and anxiety disorders, PTSD, intermittent explosive disorder, pathological gambling, eating disorder, alcohol and illicit drug use disorders, and a range of personality disorders. Results from multivariable analyses of both the number and type of disorders showed a significant association between the anger/gun-carry index and having multiple internalizing, externalizing, and personality disorders, controlling for demographic characteristics. However, schizophrenia (nonaffective psychosis) and bipolar disorder did not show net significant associations with anger/carry, possibly due to their rarity. Very few of persons in the risky category of having anger traits combined with gun access had ever been hospitalized for a mental health problem.

Policy implications

Images of mentally disturbed killers continue to pervade media reports of mass shootings, infect the public imagination, and animate a prevailing social narrative that tends to associate gun violence mainly with people with serious mental illness. The policy corollaries to this common construction of the problem suggest that we should provide better mental health treatment for people with serious psychiatric disorders and keep guns away from people with serious mental illness (e.g., have more comprehensive background checks to ensure that seriously mentally ill people are unable legally to purchase guns).

The suggestion that seriously mentally ill people need better treatment resonates with some mental health stakeholders who advocate for a better treatment system, while the suggestion that seriously mentally ill people should not be allowed to have access to firearms resonates with many gun rights advocates who want to exculpate the guns themselves. But both strategies share the same assumption: that untreated serious mental illness contributes significantly to the problem of gun violence. Is this assumption supported by evidence? If not, what is the nature of the link between psychopathology of any kind and the propensity to use a firearm to harm someone else? Is there a more accurate and policy-relevant way to think about the problem?

Research evidence to date has suggested that the large majority of people with serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and severe depression are not inclined to be violent; that only a small proportion (about 4%) of minor to serious violence is attributable to people with major psychopathology; and that interpersonal violence, even among people with mental illness is largely caused by other factors such as substance abuse (Swanson et al., 2014).

Nonetheless, the new data presented here document associations between most of the common mental disorders studied and several behaviors that are likely to heighten risk for impulsive, gun-related violence. The associations are diagnostically non-specific, though, encompassing disorders that affect substantial proportions of the population (e.g., depression, anxiety disorders) and that are not usually thought to be associated with violence (e.g., eating disorders). Only a small minority of the people with such disorders are subject to current gun restrictions based on mental disorder, as they are never involuntarily hospitalized. Nor would it be easy for authorities otherwise to identify many of them as having one of these common mental disorders, as they will never have sought treatment. Even if these common disorders could be identified, furthermore, gun exclusions that swept up such a large proportion of the general population are not likely to be politically viable.

However, it is plausible to imagine that many of the people who fall into these groups have an arrest history, particularly those who reported using illicit drugs and getting angry and engaging in physical fights. Thus, gun restrictions based on criminal records of misdemeanor violence, DUI/DWIs, controlled substance crimes, and temporary domestic violence restraining orders could be a more effective—and politically more palatable—means of limiting gun access in this high-risk group (Consortium for Risk-Based Firearms Policy, 2013a; 2013b; McGinty et al., 2014).

Table 3.

Bivariate associations (odds-ratios) of DSM-IV/CIDI disorders with gun access//carrying and anger controlling for socio-demographics (n = 5,653)1

| Guns in home | Carries guns | Guns in home and anger traits |

Carries guns and anger traits |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Internalizing disorders | ||||

| Major depression/dysthymia | 0.9 | 1.7 | 2.4* | 3.2* |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 1 | 1.4 | 2.4* | 3.3* |

| Social phobia | 0.8 | 1.3 | 2.1* | 2.0* |

| Specific phobia | 1 | 1.7 | 2.2* | 3.1* |

| PTSD | 0.8 | 2.5* | 1.8* | 4.7* |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 0.3* | 1.3 | 0.4 | 4.9* |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 0.8 | 1.7 | 2.3* | 3.3* |

| II. Externalizing disorders | ||||

| Intermittent explosive disorder | 1.1 | 2.9* | 4.3* | 9.6* |

| Conduct disorder | 1 | 1.2 | 2.5* | 12.1 |

| Oppositional-defiant disorder | 1.5 | 0.8 | 2.5* | 3.5 |

| ADHD | 0.8 | 1 | 2.5* | 2.5 |

| Pathological gambling disorder | 1.7* | 4.7* | 2.3 | 5.2* |

| Eating disorder | 1.5 | 3.2* | 3.9* | 6.6* |

| Alcohol/illicit drug abuse | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.7* | 2.4* |

| Alcohol/illicit drug dependence | 0.9 | 1.9 | 2.7* | 3.5* |

| III. Other Axis I disorders | ||||

| Bipolar disorder | 0.8 | 1.1 | 2.1* | 3.2* |

| Non-affective psychosis | 0.5 | 1.3 | 2.3 | ++ |

| IV. Axis II (personality) disorders | ||||

| Cl A (odd, eccentric) | 0.8 | 2..3* | 1.5* | 3.0* |

| Cl B (dramatic, emotional, erratic) | 1.4 | 5.0* | 3.8* | 6.9* |

| Cl C (anxious, fearful) | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.5* | 1.6 |

Table 4.

Multivariate associations (odds-ratios) of DSM-IV/CIDI disorders with gun possession//carrying and anger based on the best-fitting multivariate model controlling for socio-demographics (n = 5,653)1

| Guns in home |

Carries guns | Guns in home and has anger traits |

Carries guns and has anger traits |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing disorders | ||||

| 1 | 0.9 | 1.7* | 1.4* | 2.3* |

| 2 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 2.3* | 3.3* |

| 3+ | 0.8 | 1.1 | 2.1* | 2.5* |

| Externalizing disorders | ||||

| 1 | 1.1 | 1.7* | 3.0* | 3.8* |

| 2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 4.1* | 3.5* |

| 3+ | 0.8 | 1.5 | 2.1* | 4.2* |

| Other Axis I disorders | ||||

| Bipolar disorder | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| NAP1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Axis II disorders | ||||

| Cluster A (odd, eccentric) | 0.7 | 1.9* | 1.1 | 2.3* |

| Cluster B (dramatic, emotional, erratic) |

1.6 | 3.5* | 1.8 | 2.5 |

| Cluster C (anxious, fearful) | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.6 |

Statistically significant at p<0.05

Of the 20 respondents with lifetime NAP in the sample, four had a gun in their house (three had a conjunction with anger but none with fighting) and one carried a gun (one had a conjunction with anger but none with fighting).

Acknowledgments

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044780), and the John W. Alden Trust. A complete list of NCS publications and the full text of all NCS-R instruments can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs. Send correspondence to ncs@hcp.med.harvard.edu. During the past 3 years, Dr. Kessler has served on an advisory board for Johnson & Johnson and has had research support for his epidemiological studies from Johnson & Johnson, Shire, and Sanofi-Aventis. Some of Dr. Swanson’s effort in preparing this manuscript was supported by the Elizabeth K. Dollard Trust.

Footnotes

None of the other authors has any potential conflicts to report.

REFERENCES

- Adams JR, Drake RE. Shared decision-making and evidence-based practice. Community Mental Health Journal. 2006;42:87–105. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-9005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (DSM-IV) Fourth. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS. Public safety, mental disorders, and guns. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(6):565–566. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer JK, Peay MY. Predicting intentions to seek help from professional mental health services. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatr. 1997;31:504–513. doi: 10.3109/00048679709065072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley PF, Wirshing DA, Bhushan P, Pierre JM, Resnick SA, Wirshing WC. Lack of insight in schizophrenia: impact on treatment adherence. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:129–141. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach. Second. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh J, Carson A, Sharpe M, Lawrie S. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic review. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:395e405. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury Prevention & Control: Data & Statistics Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARSTM) [Retrieved December 11, 2013];Fatal Injury Data and Nonfatal Injury Data. 2014 from Center for Disease Control website: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

- Chong SA, Verma S, Vaingankar JA, Chan YH, Wong LY, Heng BH. Perception of the public towards the mentally ill in developed Asian country. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2007;42:734–739. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RE, Ricketts SK, McHugo GJ. Measuring hospital use without claims: a comparison of patient and provider reports. Health Services Research. 1996;31:153–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coid JW, Ullrich S, Kallis C, Keers R, Barker D, Cowden F, Stamps R. The relationship between delusions and violence: findings from the East London first episode psychosis study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(5):465e71. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy. Guns, Public Health, and Mental Illness: An Evidence-Based Approach for Federal Policy. Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence. 2013a http://www.efsgv.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/GPHMI–Federal.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy. Guns, Public Health, and Mental Illness: An Evidence-Based Approach for State Policy. Educational Fund to Stop GunViolence. 2013b http://www.efsgv.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/GPHMI-State.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, de Girolamo G, Morosini P, Polidori G, Kikkawa T, Kawakami N, Ono Y, Takeshima T, Uda H, Karam EG, Fayyad JA, Karam AN, Mneimneh ZN, Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C, de Graaf R, Ormel J, Gureje O, Shen Y, Huang Y, Zhang M, Alonso J, Haro JM, Vilagut G, Bromet EJ, Gluzman S, Webb C, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Anthony JC, Von Korff MR, Wang PS, Brugha TS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Lee S, Heeringa S, Pennell BE, Zaslavsky AM, Ustun TB, Chatterji S. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais SL, Van Dorn RA, Johnson KL, Grimm KJ, Douglas KS, Swartz MS. Community Violence Perpetration and Victimization Among Adults With Mental Illnesses. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;104:2342–2349. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- District of Columbia v. Heller. 128 S. Ct. 2783, 554U.S. 570, 171 L. Ed. 2d 637. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Drapalski AL, Milford J, Goldberg RW, Brown CH, Dixon LB. Perceived barriers to medical care and mental health care among veterans with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:921–924. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan N, Alegria M, Canino G, McGuire TG, Takeuchi D. Survey conditioning in self-reported mental health service use: randomized comparison of alternative instrument formats. Health Services Research. 2007;42:890–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund MJ, Unutzer J, Curran GM. Perceived need for alcohol, drug, and mental health treatment. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41:480–487. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards HS. Dangerous cases: crime and treatment. TIME. 2014 Nov 20; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickie I. Can we reduce the burden of depression? The Australian experience with beyondblue: the national depression initiative. Australasian Psychiatry. 2004;12(Suppl):S38–S46. doi: 10.1080/j.1039-8562.2004.02097.x-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highet NJ, Luscombe GM, Davenport TA, Burns JM, Hickie IB. Positive relationships between public awareness activity and recognition of the impacts of depression in Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40:55–58. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe JB, White AA, Kelley CL, Mingay DJ, Sanchez MJ, Loftus EF. Recall strategies and memory for health-care visits. Milbank Quarterly. 1990;68:171–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Angermeyer MC, Katschnig H. Public knowledge of and attitudes to mental disorders: a limiting factor in the optimal use of treatment services. In: Andrews G, Henderson S, editors. Unmet Need in Psychiatry. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 399–413. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM. Changes in depression awareness and attitudes in Australia: the impact of beyondblue: the national depression initiative. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40:42–46. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM. The impact of beyondblue: the national depression initiative on the Australian public's recognition of depression and beliefs about treatments. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39:248–254. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashner TM, Suppes T, Rush AJ, Altshuler KZ. Measuring use of outpatient care among mentally ill individuals: a comparison of self reports and provider records. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1999;22:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, Jin R, Pennell BE, Walters EE, Zaslavsky A, Zheng H. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005a;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, Koch JR, Laska EM, Leaf PJ, Manderscheid RW, Rosenheck RA, Walters EE, Wang PS. The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research. 2001;36:987–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Demler O, Falloon IRH, Gagnon E, Guyer M, Howes MJ, Kendler KS, Lizhen S, Walters E, Wu EQ. The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Biological Psychiatry. 2005b;58:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005c;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouse W. Gun control legislation. [Retrieved December 11, 2014];Congressional Research Service. CRS report 7-5700. RL32842. 2012 from http://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL32842.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger M, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:553–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1997;27:93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Page A, Martin G, Taylor R. Attributable risk of psychiatric and socioeconomic factors for suicide from individual-level, population-based studies: a systematic review. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;72:608e16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, Berger P, Buchheim P, Channabasavanna SM, Coid B, Dahl A, Diekstra RFW, Ferguson B, Jacobsberg LB, Mombour W, Pull C, Ono Y, Regier DA. The International Personality Disorder Examination The World Health Organization/Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration International Pilot Study of Personality Disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:215–224. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030051005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald v. City of Chicago. 561 U.S. 3025, 130 S.Ct 3020, 177 L.Ed.2nd 894. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Frattaroli S, Appelbaum PS, Bonnie RJ, Grilley A, Horwitz J, Swanson JW, Webster DW. Using Research Evidence to Reframe the Policy Debate Around Mental Illness and Guns: Process and Recommendations. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(11):e22–e26. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Webster DW, Barry CL. Gun policy and serious mental illness: Priorities for future research and policy. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65:50–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows G, Burgess P, Bobevski I, Fossey E, Harvey C, Liaw ST. Perceived need for mental health care: influences of diagnosis, demography and disability. Psycholical Medicine. 2002;32:299–309. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. More People Than Ever Before Are Receiving Behavioral Health Care In The United States States, But Gaps And Challenges Remain. Health Affairs. 2014;33(8):1416–1424. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0504. (2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R. Trends in contacts with mental health professionals and cost barriers to mental health care among adults with significant psychological distress in the United States, 1997–2002. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:2009–2014. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R. Americans' attitudes toward mental health treatment seeking: 1990–2003. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:642–651. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R. Unmet need for treatment of major depression in the United States. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:297–305. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D. Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Surgeon General. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, Elinson L, Tanielian T, Pincus HA. National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287:203–209. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES, Tylee A, Wright A, Priest RG, Rix S, Hart D. The Defeat Depression Campaign: psychiatry in the public arena. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:59–65. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrou S, Murray L, Cooper P, Davidson LL. The accuracy of self-reported healthcare resource utilization in health economic studies. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 2002;18:705–710. doi: 10.1017/s026646230200051x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Transforming Mental Health Care in America: The Federal Action Agenda: First Steps. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor BD, Dalaker J. Poverty in the United States: 2001. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2001. Current population reports. [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN, Version 8.0.1. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter PL, Stewart AL, Kaymaz H, Sobel DS, Block DA, Lorig KR. Self-reports of health care utilization compared to provider records. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2001;54:136–141. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman K, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh N, Binder R, McNiel D. Recent victimization increases risk for violence in justice-involved persons with mental illness. Law and Human Behavior. 2014 Apr;38(2):119–125. doi: 10.1037/lhb0000043. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Belik SL, Stein MB, Asmundson GJ. Correlates of perceived need for mental health care among active military personnel. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:50–57. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Jagdeo A, Cox BJ, Clara I, ten Have M, Belik SL, de Graaf R, Stein MB. Perceived barriers to mental health service utilization in the United States, Ontario, and the Netherlands. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:357–364. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J. Mental illness and new gun law reforms: The promise and peril of crisis-driven policy. JAMA. 2013;309:1233–1234. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JW, McGinty EE, Fazel S, Mays VM. Mental illness and reduction of gun violence and suicide: bringing epidemiologic research to policy. Annals of Epidemiology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.03.004. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Essock SM, Osher FC, Wagner HR, Goodman LA, Rosenberg SD, Meador KG. The social-environmental context of violent behavior in persons treated for severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(9):1523–1531. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Why the NRA Keeps Talking about Mental Illness, Rather than Guns. Lexington’s Notebook, The Economist. May 13; http://www.economist.com/blogs/lexington/2013/03/guns-and-mentally–ill. [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Houston TK, Cooper LA, Wang NY, Ford DE. Beliefs and attitudes associated with the intention to not accept the diagnosis of depression among young adults. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3:38–46. doi: 10.1370/afm.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Houston TK, Cooper LA, Wang NY, Ford DE. Attitudes and illness factors associated with low perceived need for depression treatment among young adults. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41:746–754. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volavka J, Swanson J. Violent behavior in mental illness: the role of substance abuse. JAMA. 2010;304:563–564. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Mental health treatment dropout and its correlates in a general population sample. Medical Care. 2007;45:224–229. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000244506.86885.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Angermeyer M, Borges G, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, de Girolamo G, Fayyad J, Gureje O, Haro JM, Huang YQ, Kessler RC, Kovess V, Levinson D, Nakane Y, Browne MAO, Ormel JH, Posada-Villa J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Heeringa S, Pennell BE, Chatterji S, Ustun TB. Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007a;6:177–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005a;62:603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Gruber MJ, Powers RE, Schoenbaum M, Speier AH, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Mental health service use among hurricane Katrina survivors in the eight months after the disaster. Psychiatric Services. 2007b;58:1403–1411. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.11.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005b;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley S, Jackson H, Judd F, Komiti A. Role of stigma and attitudes toward help-seeking from a general practitioner for mental health problems in a rural town. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39:514–521. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynaden D, Chapman R, Orb A, McGowan S, Zeeman Z, Yeak S. Factors that influence Asian communities' access to mental health care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2005;14:88–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0979.2005.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu R, Geddes JR, Fazel S. Personality disorders, violence, and antisocial behavior: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2012;26(5):775e92. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]