Abstract

Introduction

Several intrinsic risk factors for lower extremity injuries have been proposed, including lack of proper knee and body control during landings and cutting manoeuvres, low muscular strength, reduced balance and increased ligament laxity, but there are still many unanswered questions. The overall aim of this research project is to investigate anatomical, biomechanical, neuromuscular, genetic and demographic risk factors for traumatic non-contact lower extremity injuries in young team sport athletes. Furthermore, the research project aims to develop clinically oriented screening tools for predicting future injury risk.

Methods

Young female and male players (n=508) from nine basketball teams, nine floorball teams, three ice hockey teams, and one volleyball team accepted the invitation to participate in this four-and-half-year prospective follow-up study. The players entered the study either in 2011, 2012 or 2013, and gave blood samples, performed physical tests and completed the baseline questionnaires. Following the start of screening tests, the players will be followed for sports injuries through December 2015. The primary outcome is a traumatic non-contact lower extremity injury. The secondary outcomes are other sports-related injuries. Injury risk is examined on the basis of anatomical, biomechanical, neuromuscular, genetic and other baseline factors. Univariate and multivariate regression models will be used to investigate association between investigated parameters and injury risk.

Keywords: Sporting injuries, Risk factor, Adolescent, Lowever extremity, ACL

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study uses a multifactorial approach to investigate risk factors for traumatic lower extremity injuries.

The sample size may not be sufficient for analysing all injury types separately.

Introduction

More than 420 000 Finnish children and adolescents participate in organised sports outside of school hours, and team sports, such as ice hockey and floorball, are the most popular among this youth population.1 Unfortunately, these popular sports also include a risk of traumatic and overuse injuries. In particular, the incidence of traumatic ankle and knee joint injuries is high,2–8 most likely because players perform frequent rapid cutting manoeuvres. In addition, other traumatic injuries such as muscle strains and contusions, as well as overuse-related musculoskeletal problems in the lower extremities (LE), are common in these sports.2–8

An injury that appears to be a serious problem in many team sports is the ACL rupture.3 6 9 These affect female players more often than male players and it has been estimated that female players have approximately 4–6 times higher risk for tearing the ACL than their male counterparts.9 An ACL injury causes a long-term absence from sports and markedly increases the risk for post-traumatic degenerative joint disease.10–12

Despite the above, risk factor studies in youth sports are scarce. Moreover, most of the knowledge on the risk factors for traumatic LE injuries has come from studies that have focused on one or a few risk factors only, although it is believed that sports injuries result from a complex interaction of many factors and events.13–16

Earlier studies have revealed that LE injuries are prone to recur and that previous injury is the leading risk factor for both reinjuries and new injuries.17–19 Other risk factors that have been discussed in the sports injury literature include joint laxity,20–22 anterior pelvic tilt,23 LE malalignment,23–25 poor muscular strength and muscular imbalances,25 26 poor balance27 and deficits in neuromuscular control and movement patterns.25 28

However, very little is known about the wide variety of risk factors suggested and their potential interactions with LE injury in youth team sports. Therefore, we decided to investigate a series of different potential risk factors, and included several anatomical, neuromuscular, biomechanical, genetic and demographic screening measurements into this study to assess their role as potential predictors for traumatic LE injuries. If the screening tests could be used to detect young players with a higher risk of injury, this would represent an important advance in the development of more effective sports injury prevention.

Methods

Objectives

The overall aim of this research project is to investigate anatomical, biomechanical, neuromuscular, genetic and demographic risk factors for traumatic non-contact LE injuries in young team sport athletes. The main research question is: Which factors are the main predictors for a future traumatic non-contact LE injury? In addition, the research project aims to develop clinically oriented screening tools that have good sensitivity and specificity for predicting future LE injury risk.

Study design and definitions

This is a 4.5-year prospective cohort study with two different data collection periods. During the first 3-year study period (2 May 2011 to 30 April 2014), all new time-loss injuries, including overuse and traumatic injuries, were registered weekly, whereas over the second 1.5-year study period (1 May 2014 through 31 December 2015), two cross-sectional surveys are being conducted regarding the occurrence of new ACL injuries during the latter data collection period.

The validity and reliability of the study measurements and questionnaires were assessed in the pilot study in 2010 at the UKK Institute, Tampere, Finland. The definitions follow Fuller et al's29 guidelines for sports injury research.

Team recruitment

We invited 27 teams (with about 650 players) from Finland to participate in the study: 10 basketball, 10 floorball, 3 ice-hockey, 2 handball and 2 volleyball teams. Basketball and floorball teams were recruited from six sports clubs from the Tampere City district, Finland. Ice-hockey, handball and volleyball teams were invited via the national sports associations of these sports. Twenty-one of the teams invited were youth male and female teams (aged 13–21 years) from the two highest youth league levels, and six were adult elite female teams. The reason for inviting the adult female teams was the high percentage of young players in them.

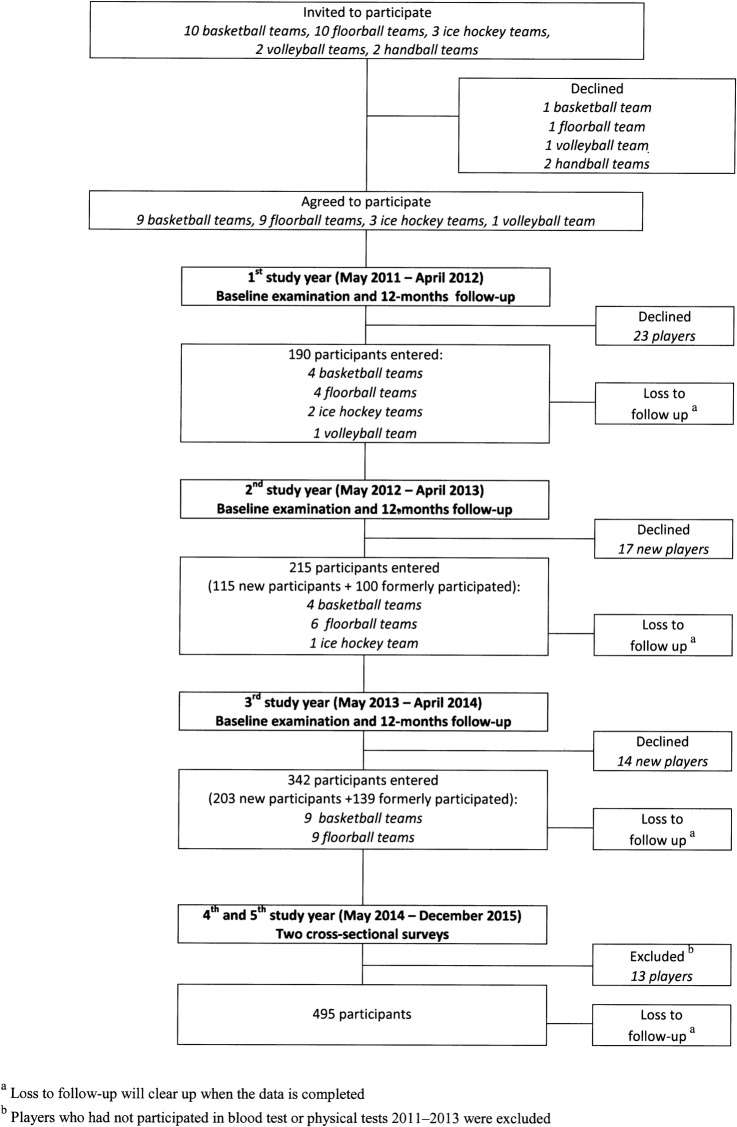

Managers of each sports club/sports association were contacted in January/February 2011 and they all agreed to support team recruitment. Thereafter, we invited the coaches of the 27 teams to an information meeting where we encouraged the teams to participate in one or more baseline examination (May 2011, April/May 2012 and/or April/May 2013) and the ensuing data collection periods (through December 2015). Coaches from nine basketball teams, nine floorball teams, three ice-hockey teams and one volleyball team agreed to take part in the study. Final participation was based on informed written consent from each player (and parent/guardian, if the player was under 18 years of age). We included players if they were official members of the participating teams. The flow of players (n=508) can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of teams and players.

First data collection period (May 2011—April 2014)

In the first 3 years of the study, the baseline examinations, including questionnaires and physical tests, were performed annually in April–May at the UKK Institute, Tampere, Finland (2 teams performed their baseline examination in September). After each baseline examination (2011, 2012 and 2013) a 12-month follow-up was conducted during which all time-loss sports injuries as well as exposure data were recorded.

Each team could choose which of the three baseline examinations they wished to complete.

However, we encouraged teams and players to participate in all three test sessions (2011, 2012 and 2013), since various factors may change over time in this young cohort. Participants who did not appear for their next baseline examination received a web-based questionnaire to check the completeness and coverage of injury and exposure data collection during the foregoing follow-up period, as well as their willingness to take part in the next follow-up year. In total, 508 players entered the study, of whom 190 players joined the study in the first year, 115 players in the second and 203 players in the third study year (figure 1).

Baseline questionnaires

At each baseline examination (2011, 2012, 2013), each player completed a detailed questionnaire covering questions about demographic information, such as age, gender, dominant leg, nutrition, alcohol and tobacco use, menstrual history, chronic illnesses, medication, oral contraceptive use, family history of musculoskeletal disorders, previous ACL injuries, playing years, player position, playing level and time-loss injuries, as well as training and playing history during the previous 12 months (see online supplementary appendix 1). The questionnaire was based on previous sports injury studies from our group.3 30–32

In addition, players completed questionnaires on their knee function (see online supplementary appendix 2) and history of low back pain (LBP) (see online supplementary appendix 3). Questions about knee function were based on the Knee and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) form,33 which has been shown to be a valid method to assess knee problems after surgical treatment. The LBP questionnaire was based on the standardised Nordic questionnaire of musculoskeletal symptoms34 and on its modified version for athletes.35 The standardised Nordic questionnaire for musculoskeletal health has been shown to be a valid and reliable method for data collection in adult populations.34

DNA sample

In total 5 mL of venous blood was extracted by an authorised health professional when players performed their first baseline examination. We will investigate the relationship between injuries and genetic variants of genes encoding for structural components of tendons and ligaments (eg, the α1 chain of type I collagen (COL1A1) gene and the α1 chain of type V collagen (COL5A1) gene).36 37

Physical tests

A comprehensive test battery was used to investigate potential anatomical, biomechanical and neuromuscular risk factors for injuries (see online supplementary appendices 4–18).31 38–40 The screening test sessions included warm-up trials and physical tests, which were performed at seven test stations (table 1). Each player spent about 6 h in total to complete all tests. Players wore shorts, a sports bra (females) and indoor basketball or floorball shoes. Some of the tests were performed without shoes (eg, balance tests, foot pronation test and anthropometrics).

Table 1.

Physical tests

| Test station | Procedures |

|---|---|

| Station I | Anthropometric measurements |

| ▸ Body weight (kg) | |

| ▸ Height (cm) | |

| ▸ Body dimensions according to Yeadon's Method41 | |

| Station II | Three-dimensional motion analyses |

| ▸ Test preparations: placing the markers | |

| ▸ 5 min warm-up by cycling | |

| ▸ Hip stability42 | |

| ▸ Running trials43 | |

| ▸ Cutting technique 90° (new test) | |

| ▸ Cutting technique 180° (new test) | |

| ▸ Vertical drop jump28 44 | |

| Station III | Quadriceps and hamstring strength test |

| ▸ 5 min warm-up by cycling and isokinetic warm-up sets | |

| ▸ Quadriceps and hamstring strength45 | |

| Station IV | Joint laxity, muscle extensibility, balance and hip strength tests |

| ▸ Knee joint laxity46 | |

| ▸ Hip abductor strength47 48 | |

| ▸ Hamstring extensibility49 | |

| ▸ Genu recurvatum50 | |

| ▸ Iliopsoas and quadriceps extensibility51 52 | |

| ▸ Hip anteversion53 | |

| ▸ Generalised joint laxity54 55 | |

| ▸ Star excursion balance test27 56 | |

| Station V | Knee and pelvic control and foot pronation tests |

| ▸ Warm-up exercises and test preparations | |

| ▸ Single leg squat38 | |

| ▸ Single leg vertical drop jump38 | |

| ▸ Vertical drop jump28 38 | |

| ▸ Foot pronation31 57 | |

| Station VI | Balance platform tests |

| ▸ 5 min warm-up by cycling | |

| ▸ Single leg balance17 | |

| ▸ Double leg balance (good balance programme B) | |

| ▸ Single leg drop jump (new test) | |

| Station VII | One repetition maximum leg press |

| ▸ Warm-up sets | |

| ▸ Leg press test31 |

Injury and exposure registration

During the first data collection period (May 2011–April 2014), all injuries were registered with a structured questionnaire, including the time of occurrence, place, cause, type, location and severity of the injury (see online supplementary appendix 19). The questions used in the injury form were based on validated questions of the previous floorball study.3 30 Five study physicians were responsible for collecting the injury data. The physicians contacted the teams once a week to check possible new injuries. After each reported injury, a study physician interviewed the injured player using the aforementioned structured questionnaire. An injury was recorded if the player was unable to fully participate in a game or practice session during the next 24 h. Severity of injury was defined as the number of days missed from training and playing. The player was defined as injured until she/he was able to train and play normally again.

During follow-up, each coach recorded player participation in practices and games on a team diary and also noted all injured players. Player attendance in a training session (yes/no), duration of a training session (h), contents of the training session (sports specific training/condition training) and attendance in each period of a game (yes/no), were recorded individually for each player. At the end of each follow-up month, the coach returned the team diary to the research group.

At the end of the first data collection period (May 2014), all participants received a web-based questionnaire to check the completeness and coverage of injury and exposure data collection during the previous follow-up year.

Second data collection period (May 2014–December 2015)

In the final 1.5 study years the participating players were followed twice (May 2015 and December 2015) with an automatic text message questionnaire (short message service, SMS) regarding the occurrence of ACL injuries of the knee during follow-up: Have you had an ACL injury of the knee (no/yes)? After each new ACL injury, the study physician or physiotherapist contacted the injured player and interviewed her/him using a structured questionnaire (see online supplementary appendix 19). The injured players were asked for separate permission to allow the researchers to check the ACL injury information from their medical records. All players who had entered the study and participated in the blood test or at least in one physical test session (2011, 2012 or 2013) were included in this latter 1.5-year follow-up (n=495).

Outcomes

The primary outcome is a traumatic LE injury (eg, ligament injury of the knee or ankle, hamstring strain) that occurs in non-contact circumstances. The secondary outcome is other sports-related injury. Injury risk is examined on the basis of anatomic, biomechanical, neuromuscular, genetic and other baseline factors (eg, age, gender, sport, previous injuries). We will also investigate the risk factors for non-contact ACL injuries, if the sample size is sufficient for the analyses.

Sample size

On the basis of the Bahr and Holme,58 the sample size needs to be 20–50 injuries to detect moderate to strong associations between risk factors and injury risk. Strong associations are defined as a relative risk higher than two. Estimates based on previous studies suggest that 0.2–0.6 non-contact LE injuries3–5 7 8 30 and 0.02 ACL injuries3 4 occur per player per year. Accordingly, we estimated that during the first 3 years of study at least 90 non-contact LE injuries will appear among participants, if we recruited 150 participants for each year (altogether 450 person-years). Correspondingly, the estimated number of ACL injuries during the total 4.5-year follow-up will be 30 injuries, where we have been able to recruit 150 new participants in each study year (2011, 2012 and 2013) and if we have managed to follow them until the end of the study (total 1575 person-years).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics of baseline characteristics of the participants will be reported by using mean, SD and 95% CIs. The injury incidence will be expressed as the number of injuries per 1000 h of training and playing (injuries registered during the first data collection period May 2011–April 2014) and as the number of injuries per person-years (ACL injuries during the total 4.5-year follow-up). Univariate and multivariate regression models will be applied to investigate the association between the investigated parameters and injuries in order to identify the risk factors. In the data analysis by multilevel modelling we will take the clusters into account. Adjusted and unadjusted results will be presented. A p value <0.05 is considered significant.

Discussion

Several intrinsic risk factors have been suggested to be associated with increased LE injury risk, but, at the time being, there is limited knowledge on these. As this study combines measures of anatomical, biomechanical, neuromuscular, genetic and demographic factors, we will be able to study multiple factors that can predispose the player to a traumatic LE injury. Also, we can assess the relative importance of the different factors and their interactions. We will also perform risk factor analyses for specific injury subgroups, such as ACL injury, as well as other potential injury types where the number is sufficient.

Basketball, floorball, ice hockey and volleyball were chosen in this study, because they are the most popular team sports among youth in Finland. They also share somewhat similar injury patterns as well as comparable playing seasons. One playing season lasts approximately 7 months, from September/October to March/April, thus all the participating teams performed the baseline examinations during the preseason. Twenty teams performed the baseline tests in April/May, and the remaining two teams conducted them in September, due to their team schedule.

This study will provide valuable information, assessing the validity of screening methods for youth sport. Most of the screening tests used in this study are simple and easy to manage, meaning that implementation at the grass roots level will be possible. In addition, successful results from this project would provide a major contribution to tailor preventive methods, the effectiveness of which could be tested in prevention studies.59 Better knowledge on risk factors will be used to optimise the current training programmes and target these to populations at risk. The findings will also be beneficial and adaptable to other pivoting sports with high sports injury risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the players, coaches and contact persons of each participating team for the excellent cooperation. They are grateful to physiotherapist Irja Lahtinen for her contribution during the long study project. They also thank all study assistants for participating in this project. They acknowledge collaboration of the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture, the Competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility Area of Tampere University Hospital and the Finnish National Olympic Committee, for financial support of the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors participated in conceiving and designing the study, revising the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript. KP is the principal researcher and responsible for club recruitments (with TV), overall study arrangements, data collection and for familiarising study assistants with screening tests. GM, KS, TK and RB selected the measurements for the comprehensive testing battery, except for hip stability (MTR), running trials (J-PK), cutting technique 180° (KP), and iliopsoas and quadriceps extensibility (MTR). JA, JPe and J-PK were responsible for the 3D-motion capture technology and measurements. MTR contributed to the anatomical and balance tests. JPa and PK recruited and supervised the study physicians who carried out injury data collection. TV, AH and UMK recruited the study assistants and supervised data procedures. KP and MTR wrote the first draft of the paper. KP is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was mainly supported by grants from the Ministry of Education and Culture, Finland. Grants were also received from the Competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility Area of Tampere University Hospital, Finland, and the Finnish National Olympic Committee, Finland.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Before starting the study, the Ethics Committee of Pirkanmaa Hospital District, Tampere, Finland, (ETL-code R10169) approved the study plan. The study was conducted by following medical research ethics (the Declaration of Helsinki) and guidelines for good scientific practice. The participants took part in the study voluntarily, and signed a written consent of participation. For players under 18 years of age, their parents/guardians also provided written informed consent. The aim and execution of the study were clarified in the consent. The participants were also told that they are free to withdraw from the study at any time without providing a reason. The participants were asked for separate permission to allow the researchers to check possible injury information on their medical records. The collected information is stored in a locked room at the UKK Institute. The research information is handled anonymously according to the confidential obligations, and the collected data are only available to the research group. The data registry will be deleted 10 years after finishing the study. The data collected will be published anonymously.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kansallinen liikuntatutkimus 2009–2010: lapset ja nuoret (National exercise survey 2009–2010: children and adolescents). 2010. http://www.sport.fi/system/resources/W1siZiIsIjIwMTMvMTEvMjkvMTNfNDRfMzJfMjgwX0xpaWt1bnRhdHV0a2ltdXNfbnVvcmV0XzIwMDlfMjAxMC5wZGYiXV0/Liikuntatutkimus_nuoret_2009_2010.pdf (accessed 10 Sep 2015).

- 2.Snellman K, Parkkari J, Kannus P et al. Sports injuries in floorball: a prospective one-year follow-up study. Int J Sports Med 2001;22:531–6. 10.1055/s-2001-17609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasanen K, Parkkari J, Kannus P et al. Injury risk in female floorball: a prospective one-season follow-up. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2008;18:49–54. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00640.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messina DF, Farney WC, DeLee JC. The incidence of injury in Texas High School Basketball. A prospective study among male and female athletes. Am J Sports Med 1999;27:294–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borowski LA, Yard EE, Fields SK et al. The Epidemiology of US High School Basketball Injuries, 2005–2007. Am J Sports Med 2008;36:2328–35. 10.1177/0363546508322893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hootman JM, Dick R, Agel J. Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention strategies. J Athl Train 2007;42:311–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agel J, Harvey EJ. A 7-year review of men's and women's ice hockey injuries in the NCAA. Can J Surg 2010;53:319–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verhagen EALM, Van der Beek AJ, Bouter LM et al. A one season prospective cohort study of volleyball injuries. Br J Sports Med 2004;38:477–81. 10.1136/bjsm.2003.005785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: part 1, Mechanisms and risk factors. Am J Sports Med 2006;34:299–311. 10.1177/0363546505284183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsen E, Jensen PK, Jensen PR. Long-term outcome of knee and ankle injuries in elite football. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1999;9:285–9. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1999.tb00247.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myklebust G, Holm I, Maehlum S et al. Clinical, functional, and radiologic outcome in team handball players 6 to 11 years after anterior cruciate ligament injury. A follow up study. Am J Sports Med 2003;31:981–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL et al. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:1756–69. 10.1177/0363546507307396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meeuwisse WH. Assessing causation in sport injury: a multifactorial model. Clin J Sports Med 1994;4:166–70. 10.1097/00042752-199407000-00004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lysens S, Steverlynck A, van der Auweele Y et al. The predictability of sports injuries. Sports Med 1984;1:6–10. 10.2165/00007256-198401010-00002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Mechelen W. Incidence, severity, aetiology and prevention of sports injuries. A review of concepts. Sports Med 1992;14:82–99. 10.2165/00007256-199214020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taimela S, Kujala UM, Österman K. Intrinsic risk factors and athletic injuries. Sports Med 1990;9:205–15. 10.2165/00007256-199009040-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH, Hartmann SE. Evaluation of risk factors for injury in adolescent soccer: implementation and validation of an injury surveillance system. Am J Sports Med 2005;33:1882–91. 10.1177/0363546505279576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hägglund M, Waldén M, Ekstrand J. Previous injury as a risk factor for injury in elite football: a prospective study over two consecutive seasons. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:767–72. 10.1136/bjsm.2006.026609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waldén M, Hägglund M, Ekstrand J. High risk of new knee injury in elite footballers with previous anterior cruciate ligament injury. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:158–62. 10.1136/bjsm.2005.021055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Söderman K, Alfredsson H, Pietila T et al. Risk factors for leg injuries in female soccer players: a prospective investigation during one out-door season. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2001;9:313–21. 10.1007/s001670100228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myer GD, Ford KF, Paterno MV et al. The effects of generalized joint laxity on risk of anterior cruciate ligament injury in young female athletes. Am J Sports Med 2008;36:1073–80. 10.1177/0363546507313572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konopinski MD, Jones GJ, Ed C et al. The effect of hypermobility on the incidence of injuries in elite level professional soccer players. A cohort study. Am J Sports Med 2012;40:763–9. 10.1177/0363546511430198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKeon JMM, Hertel J. Sex differences and representative values for 6 lower extremity alignment measures. J Athl Train 2009;44:249–55. 10.4085/1062-6050-44.3.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shambaugh JP, Klein A, Herbert JH. Structural measures as predictors of injury in basketball players. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1991;23:522–7. 10.1249/00005768-199105000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonci CM. Assessment and evaluation of predisposing factors to anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Athl Train 1999;34:155–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knapik JJ, Bauman CL, Jones BH et al. Preseason strength and flexibility imbalances associated with athletic injuries in female collegiate athletes. Am J Sports Med 1991;19:76–81. 10.1177/036354659101900113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plisky PJ, Rauh MJ, Kaminski TW et al. Star excursion balance test as a predictor of lower extremity injury in high school basketball players. J Orth Sports Phys Ther 2006;36:911–19. 10.2519/jospt.2006.2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR et al. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med 2005;33:492–501. 10.1177/0363546504269591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuller CW, Ekstrand J, Junge A et al. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2006;16:83–92. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00528.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasanen K, Parkkari J, Pasanen M et al. Neuromuscular training and the risk of leg injuries in female floorball players: cluster randomized controlled study. BMJ 2008;337:96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nilstad A, Andersen TE, Bahr R et al. Risk factors for lower extremity injuries in elite female soccer players. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:940–8. 10.1177/0363546513518741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steffen K, Myklebust G, Andersen TE et al. Self-reported injury history and lower limb function as risk factors for injuries in female youth soccer. Am J Sports Med 2008;36:700–8. 10.1177/0363546507311598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roos EM, Roos HP, Ekdahl C et al. Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS)—validation of a Swedish version. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1998;8:439–48. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1998.tb00465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A et al. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. App Ergonomics. 1987;18:233–7. 10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bahr R, Andersen SO, Loken S et al. Low back pain among endurance athletes with and without specific back loading—A cross-sectional survey of cross-country skiers, rowers, orienteerers, and non-athletic controls. Spine 2004;29:449–54. 10.1097/01.BRS.0000096176.92881.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Posthumus M, September AV. The COL5A1 gene is associated with increased risk of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures in female participants. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:2234–40. 10.1177/0363546509338266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Posthumus M, September AV, Keegan M et al. Genetic risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament ruptures: COL1A1 gene variant. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:352–6. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.056150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stensrud S, Myklebust G, Kristianslund E et al. Correlation between two-dimensional video analysis and subjective assessment in evaluating knee control among elite female team handball players. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:589–95. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.078287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kristianslund E, Krosshaug T. Comparison of drop jumps and sports-specific sidestep cutting. Implications for anterior cruciate ligament injury risk screening. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:684–8. 10.1177/0363546512472043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kristianslund E, Faul O, Bahr R et al. Sidestep cutting technique and knee abduction loading: implications for ACL prevention exercises. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:779–83. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeadon MR. A method for obtaining three-dimensional data on ski jumping using pan and tilt cameras. Int J Sport Biomech 1989;5:238–47. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hardcastle P, Nade S. The significance of the trendelenburg test. J Bone Joint Surg 1985;67:741–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kulmala J-P, Avela J, Pasanen K et al. Forefoot strikers exhibit lower running-induced knee loading than rearfoot strikers. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2013;45:2306–13. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31829efcf7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Reliability of landing 3D motion analysis: implications for longitudinal analyses. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007;39:2021–8. 10.1249/mss.0b013e318149332d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brosky JA Jr, Nitz AJ, Malone TR et al. Intrater reliability of selected clinical outcome measures following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1999;29:39–48. 10.2519/jospt.1999.29.1.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berry J, Kramer K, Binkley J et al. Error estimates in novice and expert raters for the KT-1000 arthrometer. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1999;29:49–55. 10.2519/jospt.1999.29.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thorborg K, Bandholm T, Schick M et al. Hip strength assessment using handheld dynamometry is subject to interested bias when testers are of different sex and strength. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2013;23:487–93. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01405.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thorborg K, Bandholm T, Holmich P. Hip- and knee-strength assessment using a hand-held dynamometer with external belt-fixation are inter-tester reliable. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:550–5. 10.1007/s00167-012-2115-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davis DS, Quinn RO, Whiteman CT et al. Concurrent validity of four clinical tests used to measure hamstring flexibility. J Strength Cond Res 2008;22:583–8. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31816359f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fish DJ, Kosta CS. Genu recurvatum: idendification of three distinct mechanical profiles. J Prosthet Orthot 1998;10:26–32. 10.1097/00008526-199801020-00003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harvey D. Assessment of the flexibility of elite athletes using the modified Thomas test. Br J Sports Med 1998;32:68–70. 10.1136/bjsm.32.1.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim GM, Ha SM. Reliability of the modified Thomas test using a lumbo pelvic stabilization. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:447–9. 10.1589/jpts.27.447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruwe PA, Gage JR, Ozonoff MB et al. Clinical determination of femoral anteversion: a comparison with established techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992;74:820–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beighton P, Solomon L, Soskolne CL. Articular mobility in an African population. Ann Rheum Dis 1973;32:413–18. 10.1136/ard.32.5.413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boyle KL, Witt P, Riegger-Krugh C. Intrarater and interrater reliability of the Beighton and Horan joint mobility index. J Athl Train 2003;38:281–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kinzey SJ, Armstrong CW. The reliability of the star-excursion test in assessing dynamic balance. J Ortop Sports Phys Ther 1998;27:356–60. 10.2519/jospt.1998.27.5.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shultz SJ, Carcia CR, Gansneder BM et al. The independent and interactive effects of navicular drop and quadriceps angle on neuromuscular responses to a weight-bearing perturbation. J Athl Train 2006;41:251–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bahr R, Holme I. Risk factors for sports injuries—a methodological approach. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:384–92. 10.1136/bjsm.37.5.384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leppänen M, Aaltonen S, Parkkari J et al. Interventions to prevent sports related injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med 2014;44:473–86. 10.1007/s40279-013-0136-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]