Abstract

Introduction

Sports clubs form a potential setting for health promotion, but the research is limited. The aim of the Health Promoting Sports Club (HPSC) study was to elucidate the current health promotion activities of youth sports clubs and coaches, and to investigate the health behaviours and health status of youth participating in sports clubs compared to non-participants.

Methods and analysis

The study design employs cross-sectional multilevel and multimethod research with aspirations to a prospective cohort study in the next phase. The setting-based variables at sports clubs and coaching levels, and health behaviour variables at the individual level, are investigated using surveys; and total levels of physical activity are assessed using objective accelerometer measurements. Health status variables will be measured by preparticipation screening. The health promotion activity of sports clubs (n=154) is evaluated by club officials (n=313) and coaches (n=281). Coaches and young athletes aged 14–16 (n=759) years evaluate the coaches’ health promotion activity. The survey of the adolescents’ health behaviours consist of two data sets—the first is on their health behaviours and the second is on musculoskeletal complaints and injuries. Data are collected via sports clubs (759 participants) and schools 1650 (665 participants and 983 non-participants). 591 (418 athletes and 173 non-athletes) youth, have already participated in preparticipation screening. Screening consists of detailed personal medical history, electrocardiography, flow-volume spirometry, basic laboratory analyses and health status screening, including posture, muscle balance, and static and dynamic postural control tests, conducted by sports and exercise medicine specialists.

Ethics and dissemination

The HPSC study is carried out conforming with the declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was received from the Ethics Committee of Health Care District of Central Finland. The HPSC study is close-to-practice, which generates foundations for development work within youth sports clubs.

Keywords: Athlete, Health promotion, Sports medicine, Sport

Sports clubs are the main setting for leisure for youth in many parts of the world, and especially in Nordic countries. In Finland, club activity draws about half (46%) of the child and adolescent population aged 10–16 years.1 Owing to their wide reach and informal educational nature, club activities form a potential setting for health promotion.2 The model of a Health Promoting Sports Club was established in Finland in 2004.3 Prior to this, there were no concepts or models in the sports field following settings-based health promotion principles.

Studies on health promotion at the sports club level have demonstrated that youth sports clubs and/or coaches have a positive orientation on health promotion on average, but have not invested in implementation to the same degree; neither at club nor coaching levels.4–7 In addition, research indicates that comprehensive health promotion orientation at the club level generates a higher level of guidance activity at club level.8 Internationally, and particularly in Australia, studies have focused on upper level sports organisations, such as national/regional sports federations.9 10

Physical activity and health behaviours of youth participating in sports clubs

It is a common belief that those who participate in sports club activities automatically have a more physically active and healthier lifestyle than non-participants. Research findings on these issues are, however, inconsistent. A quarter (24%) of the general population of Finnish children and adolescents aged 11–15 years meet the current physical activity (PA) guidelines.1 11 At 15 years of age, those figures are 17% for boys and 10% for girls.1 In addition, recent reports in Nordic countries have indicated that approximately one-third of sports club participants lack the recommended level of PA.12–14

From the perspective of comprehensive athletic development, the focus on PA and sports-based physical, technical and tactical factors is too narrow and the current health promotional challenges cannot be reached. Lifestyle-related challenges, for example, high levels of screen time, are the same for a group of sports club participants as for non-participants.14 The same applies, as an example, to substance use, as it has been shown that sports club participants smoke less,15 16 but are more likely to use smokeless tobacco;17 18 binge-drink,17 and use unnecessary supplements19 and performance enhancing drugs.20

Health of youth participating in sports clubs, and their risk of injury

Health benefits of PA are well documented, whereas health benefits of certain sports are much less studied and/or study designs have been weak.21 In addition to the health benefits of PA and sports, the risks need to be addressed. With increasing amount and intensity of PA, the risk of injuries and adverse events, such as sports injuries22 23 or unexpected sudden death,24 also increases. The incidence of asthma25 and its symptoms26 is higher among adult athletes.

The aims of the Health Promoting Sports Club (HPSC) study

There is limited research on youth sports clubs as health promoting settings. In addition, there is little systematic research on the health behaviours and health status of sports club participants, including top-aiming young athletes, especially compared to their non-sporting peers. Usually, sports club participants have been classified as one homogenous group, without recognising their training volumes or level of completion, as has been carried out in this study.

The Health Promoting Sports Club (HPSC) study uses multicentre research and is executed in cooperation with the University of Jyväskylä, UKK Institute (Research Center for Health Promotion Research), and six national Sports and Exercise Medicine Centres of Excellence, namely Clinic of Sports and Exercise Medicine (Helsinki), LIKES Foundation for Sport and Health Sciences/Mehiläinen Sports Clinic (Jyväskylä), Kuopio Research Institute of Exercise Medicine (Kuopio), Tampere Research Center of Sports Medicine (Tampere), Paavo Nurmi Centre (Turku), and Department of Sports and Exercise Medicine, Oulu Deaconess Institute (Oulu).

The first aim of the study is to survey health promotion orientation and activity of youth sports clubs and coaches. The second aim is to examine the health behaviours and status of youth participating in sports clubs compared to their non-participating peers. The third aim is to investigate whether there are associations between sports clubs orientation and activity of clubs and/or coaches in health promotion, and health of the participants. Specific research aims are:

Health promotion orientation and activity of youth sports clubs and coaches:

To what extent do sports club representatives (club officials and coaches) perceive health promotion is included in their clubs operational orientation?

How actively do youth sports clubs guide their coaches in health promotion and sports injury prevention (club official and coach evaluations)?

To what extent do youth sports coaches implement health promotion and sports injury prevention as a part of their coaching practice (coach and participant evaluations)?

Health behaviours and health status of youth participating in sports clubs:

- What kind of health habits (eg, overall PA, training history, training volume, screen time, diet, sleep, smoking, alcohol consumption, snuff/oral tobacco use) do youth participating in sports clubs have compared to non-participants?

- For example, are there differences in overall PA and sedentary behaviour (measured using questionnaires, dairies and accelerometers) of those participating in sports club activities compared to those not participating?

What is the prevalence of sports-related injury (organised sports, school sports and other activities separately, and acute and stress injuries separately) and pain suffered by sports club participants and non-participants? Is there a difference in use of medication between these groups?

What kind of preparticipation screening status (medical history, electrocardiography, flow-volume spirometry, laboratory tests, and posture and muscle balance test) do sports club participants have compared to non-participants? Which components of the structured clinical examination should be included in the preparticipation screening of young athletes?

Associations between health promotion orientation, activity of sports clubs and coaches, and health of participants:

Are there differences in health behaviours and/or health status of young participants between higher and lower health promoting sports clubs: by the clubs’ orientation and/or clubs’ guidance activity and/or coaches’ implementation activity?

Are there differences in the prevalence and gravity of young participants’ sports-related injuries between higher and lower health promoting sports clubs: by the clubs’ orientation and/or clubs’ guidance activity and/or coaches’ implementation activity?

Methods

Study design

This consortium and multidisciplinary study uses a cross-sectional design. The setting-based variables at sports club and coaching levels, and health behaviour variables at the individual level, are being examined by surveys; PA levels are assessed using objective accelerometer measurements. Health status variables were measured by preparticipation clinical examination and several tests.

The health promotion orientation and activity of sports clubs was evaluated by club officials and coaches. The coaches’ health promotion activity was evaluated by coaches themselves, as well as young sports club participants. Health behaviours, sports injuries and musculoskeletal health were self-evaluated by sports club participants (questionnaire via sports clubs) and non-participants (questionnaire via schools). Preparticipation screening was performed for 591 youth. The medical examination consisted of detailed personal medical history, resting ECG, flow-volume spirometry, basic laboratory tests, and clinical examination including posture and muscle balance tests, by sports and exercise medicine specialists. All youth were aged between 14 and 16 years and represented both genders.

Data collection

The HPSC data collection was started by surveys in the middle of the main competition season from January to May 2013 for winter sports, and from August to December 2013 for summer sports. Comparison data for non-sports club participants was collected via schools (9th grades) similarly in two stages and approximately within the same timeframe. Complementary data, including club-participants and non-participants, were compiled in Spring 2014. Preparticipation screening data were mainly collected between August 2013 and April 2014. All data sets will be supplemented by the end of 2015.

Sampling

The sampling of sports club-based data was carried out in a two-stage process, first, with the clubs, and second, with the respondents and/or study participants. A similar procedure was undertaken for school-based data. The data description below is for the data collected until April 2015.

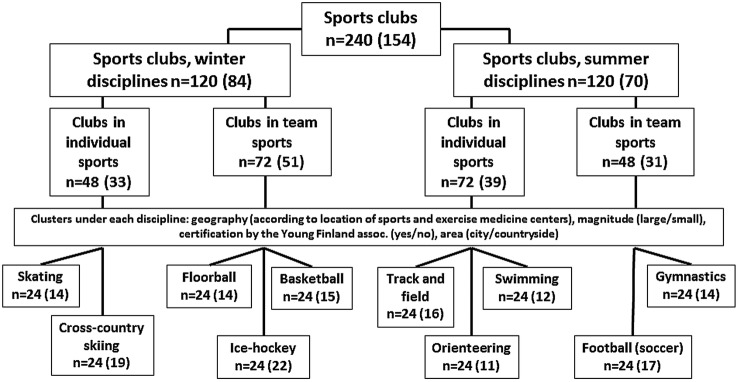

The sports club sample

To produce a nationally representative sample of the most popular sports for youth in Finland, a total of 240 youth sports clubs from 10 sports disciplines were targeted; 24 from each discipline. The sample size of the clubs was power calculated by Stata V.11.0 using data from Kokko.8 The first step of club sampling was to stratify sports clubs by the following criteria: (1) winter and summer sports, depending on the main competition season, and (2) team and individual sports. Thereafter, the most popular sporting disciplines (winter sports: basketball, cross-country skiing, floorball, ice-hockey and skating; and summer sports: football (soccer), gymnastics, orienteering, swimming and track and field) were chosen.

The next step was completed separately for each discipline. Clubs were further stratified depending on: (1) geographical location (six areas of Centres of Excellence in Sports and Exercise Medicine covering the six largest cities, about a third of the population in Finland), (2) magnitude (larger and smaller), (3) certification by The Young Finland Association (yes or no), and (4) area type (city vs countryside). Thereafter, to ensure objective and representative sampling of the clubs, discretionary rather than randomised sampling of clubs was performed. Twenty-four clubs were selected from each sport and the total sample consisted of 240 youth sports clubs.

Ninety-one of 120 winter sports clubs were reached. Eighty-four clubs participated successfully, that is, had representatives from each target group (club officials, coaches and youth) and returned club-based background information (figure 1). Similarly, for summer sports, 84 of 120 clubs were reached and 70 participated successfully. In total, 154 youth sports clubs out of 240 participated (64%) in the HPSC study.

Figure 1.

Cluster sampling (realised sample in brackets) of sports clubs in Health Promoting Sports Club (HPSC) study.

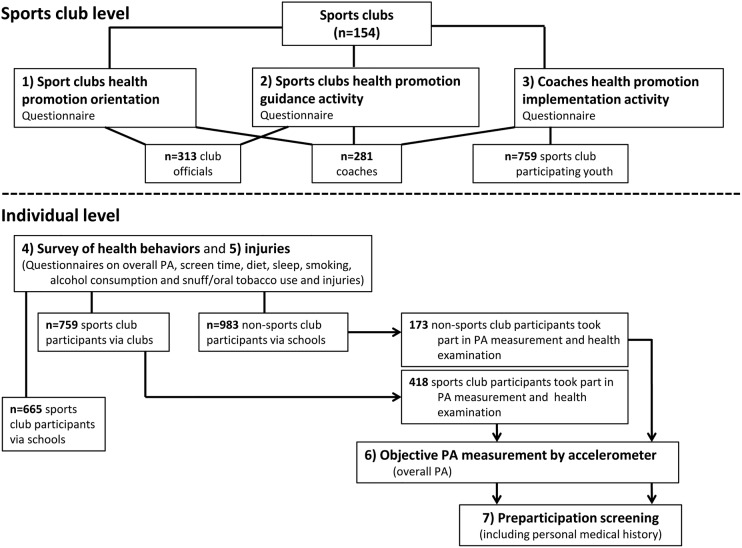

The sports club officials and coaches sample

Following the club sampling, the respondents (surveys) and study participants (youth preparticipation screening) from sports clubs were selected (figure 2). For the surveys, 3–5 club officials and 3–5 coaches were targeted from each club. Selection was discretionary, in cooperation with a contact person from each club to ensure that certain criteria were met. The criterion for being a club official was that the person held an official status, such as chairman of the club, member of the executive committee or head of coaching or junior activities. The criterion for coaches was that the coach in question was coaching youth 14–16 years of age (target group of the youth) at the time. Overall, 625 club officials and 593 coaches were contacted, of which 313 club officials (50%) and 281 coaches (47%) participated.

Figure 2.

Realised data and respondents/study participants of Health Promoting Sports Club (HPSC) study. PA, physical activity.

The sampling of youth participating in sports clubs for the health behaviour survey

The sampling of youth participating in sports clubs (for surveys) was tailored separately for team and individual sports and had some differences between winter and summer sports depending on the timing of the data collection. Fifteen-year old (9th graders) youth were targeted. Owing to differing timing for data collection, different age cohorts were targeted: for winter sports, youth born in 1997 (9th graders in Spring 2013), and for summer sports youth born in 1998 (9th graders in Autumn 2013). Plus-minus 1 year was accepted at sampling stage. For the analysis of data, only those who were 14–16 years of age were accepted. For each club, five boys and five girls was aimed for, but this criterion was reduced to a minimum of three per gender because there were simply not enough targeted age youth in each club, especially for the individual sports. Sample size was power calculated by Stata V.11.0 using data from Kokko et al.14

Sampling was realised as follows: for team sports, in those clubs that had several teams, only one was randomly selected. If a club only had one team, that team was automatically used. Thereafter, a club was asked to provide a list of participants from the given team to the researchers, who selected the individuals randomly. For individual sports, a list of all eligible (given age range) youth was provided to researchers, and similarly in team sports, individuals were randomly selected. Overall, 1889 youth participating in sports clubs were invited to complete the questionnaires. Less than half (759/40%) completed the health behaviour questionnaire (figure 2). The loss in data collection will be analysed with the information of those sports club participants who did not participate in the surveys, including which club and sport they represented, how many boys/girls, etc.

The school-based sample of non-sport club participants for health behaviour survey

School-based data (surveys) were collected in two portions following the sports clubs data collection timing. Ten secondary schools from every six districts of the Centres of Excellence in Sports and Exercise Medicine were targeted per data collection. Equal portions of large and small schools and city versus countryside were aimed for in sampling, but needed to be adjusted depending on city size and willingness of the schools to participate. In smaller cities, such as Jyväskylä and Kuopio, there were not enough smaller or countryside schools, or, these type of schools refused to participate. Overall, 159 schools were contacted and one hundred participated (63%). In Winter 2013, 65 schools were contacted and 46 participated (71%). Similarly, in Autumn 2013, 79 schools were contacted and 48 participated (61%). In early 2014, the preparticipation screening data needed additional non-sports club participants. Therefore, an extra 15 schools were contacted, of which six participated. A minor portion of the schools were the same in both data collections, but, as described earlier, the responding class was different. One class of 9th graders was asked to respond from each school. The class was randomly selected. In total, there were 2074 9th graders in these school classes, and 1650 (80%) completed the health behaviour questionnaire (figure 2).

The sample of youth for sports injury and musculoskeletal health survey

The data for the sports injury and musculoskeletal health survey were collected similarly to the health behaviour survey. The sports injury and musculoskeletal health survey was executed within 2 weeks after the health behaviour survey. The same youth were invited to answer the questionnaire. In total, 2096 youth completed the sports injury and musculoskeletal health questionnaire, of which 1168 were sports club participants (via sports clubs and schools) and 928 were non-participants (via schools).

The sample for youth preparticipation screenings

Sample size for the youth preparticipation screening was power calculated by DDS Research Researchers toolkit (used in 29 August 2011) using the prevalence of asthma (population 8% vs athletes 15%).27 Six hundred youth, of whom 372 were sports club participants and 228 non-participants, were aimed at for the sample. Half of the preparticipation screenings (300 in total, of which 186 were from sports club participants and 114 from non-participants) were planned to be completed in the timeframe of winter sports (January to May 2013) and half (300 with a ratio of 186/114) similarly, within the timeframe of the summer sports (August to December 2013). Both preparticipation screening timeframes were expanded in order to complete enough examinations. Each Centre of Excellence in Sports and Exercise Medicine was aimed to execute one hundred preparticipation screening visits, 50 in both timeframes, divided between 62 (31 by 2) sports club participants and 38 (19 by 2) non-participants.

Youth who were invited to engage in preparticipation screening were randomly selected from the survey data mentioned above (respondents)—sports club participants from sports club-based data and non-participants from school-based data. Overall, 591 preparticipation screening visits were completed, of which three failed to be completed (table 1). The ratio between sports club participants and non-participants was not achieved as planned, due to lack of interest among non-sports club participants. In the final data for analysis, 415 sports club participants and 173 non-participants, 588 in total (figure 2), were included. The completion of preparticipation screening visits varied between 92 and 107 among the Centers of Excellence in Sports and Exercise Medicine.

Table 1.

Study participants of preparticipation screening by their gender and sports club participation (frequency)

| Boys | Girls | In total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sports club participants | 198 | 217 | 415 |

| Non-participants | 63 | 110 | 173 |

| Failed to complete | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| In total | 263 | 328 | 591 |

Measurements

Surveys

Six different questionnaires were used in this study. All were internet-based and answered online by club officials, coaches and sports-club participants during their spare time, and by pupils during a school day in a class supervised by a teacher.

The first questionnaire was used to verify the background information of clubs. This questionnaire consisted of nine questions regarding the club in question, for example, whether the club was a general club or specialised in one sport, what the discipline of the club was, if the club was certified or not, and what the membership was. This questionnaire was answered by the contact person at each club.

The second questionnaire was directed at sports club officials, who evaluated the club's health promotion orientation and guidance activity. The health promotion orientation was examined by the HPSC index5 and health promotion guidance activity by three question-batteries created in the initial HPSC study.28

The third questionnaire was completed by coaches, who evaluated three aspects: (1) the club's health promotion orientation, (2) the club's health promotion guidance activity and (3) their own health promotion and injury prevention implementation activity. In addition to the aforementioned measurements of HPSC index and the clubs’ health promotion guidance activity, coaches’ health promotion and injury prevention implementation activity were examined by three existing question-batteries.29 The questionnaires for club officials and coaches also consisted of self-evaluations on their health behaviours.

The fourth and fifth questionnaires were targeted at boys and girls aged 14–16 years. The fourth questionnaire focused on the health behaviours of the adolescents, including self-evaluated overall PA. The questionnaire for youth participating in sports clubs included extra questions compared to non-participants. These additional questions specified their sports activities and included young athletes’ evaluation of their coaches’ health promotion and injury prevention activity.29 The fifth questionnaire focused on injuries and musculoskeletal health of the adolescents. The sixth questionnaire was targeted at those adolescent who attended the preparticipation screening, and ascertained family history of diseases, as well as family history and information on growth, nutrition, sleeping and health status of the adolescents. The queries used in these questionnaires were compiled from previously validated questionnaires in other studies, such as the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study30 and similar reports.8 15 31–33

Objective PA measurement

PA level of the youth was objectively measured by Hookie Meter V.2.0 accelerometer (Hookie Technologies Ltd, Helsinki, Finland). The accelerometer was set up during the first preparticipation screening appointment, kept for a week and returned at the second appointment. One unit (Jyväskylä) used a different protocol—without second appointment. There the accelerometers were returned via postal mail. In addition, PA was recorded by a diary, in which the adolescents were asked to record the time of waking up and going to bed as well as all PAs performed during the day (before, during and after school).

Preparticipation screening

The preparticipation screening protocol consisted of two separate visits, a main session and a feedback session. The main visit lasted approximately two and half hours and consisted of detailed personal medical history, resting ECG, blood pressure measurement, flow-volume spirometry, fasting blood samples and health status examination including assessment of risk of future injury (box 1). The examination was performed by specialists in sports and exercise medicine.

Box 1. Contents and timetable of the pre-participation screening in the Health Promoting Sports Club (HPSC) study.

Health Screening Questionnaire was filled at home with the parents. Informed written consent was included.

Examination started with filling in the questionnaire focused on previous injuries and musculoskeletal health of the adolescents (those who had not fulfilled the questionnaire previously). Time allocation: 30 min.

- The measurements during the examination were obtained in the following order. Time allocation: 60 min.

- height, weight

- resting blood pressure

- resting ECG

- fasting blood samples

- spirometry and bronchodilatation tests

Preparticipation screening by a physician. Time allocation: 60 min.

A Hookie Meter V.2.0 accelerometer (Hookie Technologies Ltd) and 1 week physical activity questionnaire were distributed with instructions, and the device was set up. Time allocation: 30 min. The accelerometer was returned 1 week later and the physician gave verbal and written feedback from the findings and results of the pre-participation screening performed and feedback session. Time allocation: 15 min.

Resting blood pressure was measured in sitting position from the left arm after a 5-min rest.34 The measurement was performed with a validated, cuff-style oscillometric (automated) device.34 A correct sized brachial cuff was placed with the lower edge about 2–3 cm above the elbow crease.34 The device recorded the oscillations of pressure in a cuff during gradual deflation, and systolic and diastolic pressures were estimated indirectly according to an empirically derived algorithm.34 Two independent consecutive measurements were taken at an interval of 1 min. If there was >10 mm Hg difference in systolic or diastolic pressure between the first and second measurements, a third reading was obtained after an interval of 1 min. The pulse pressure was calculated as the difference between systolic and diastolic pressure.35

A standard 12-lead resting ECG was recorded after a 5 min rest with participants in supine position.36 ECGs will be analysed digitally to provide detailed data on the duration and amplitudes of all segments of the P wave, QRS complex and T wave in all 12 leads, with amplitudes recorded to the nearest 100th of a millivolt and times recorded to the nearest millisecond.36 Seven quantitative ECG measurements will be extracted for each subject: heart rate; PR interval; QRS duration and axis; the sum of S wave amplitude in lead V1 and the maximum R wave in lead V5 or V6; T axis; and QT interval.36 These ECG measurements are believed to be correlates of heart rate, conduction, left ventricular mass and repolarisation.36

Blood samples were taken after fasting for at least 10 h. Basic blood count was analysed by normal laboratory method using automatic equipment. Serum was separated by normal methods and stored in −75°C for later analysis.

Flow-volume spirometry was measured according to American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines,37 using a flow-volume spirometer (Medikro Pro 909, Medikro oy, Kuopio, Finland). Spirometry results were expressed as per cent of personal age-matched, size-matched and sex-matched predicted values for the Finnish population.38 Furthermore, to assess the reversibility of possible airway obstruction, a bronchodilation test was performed according to ATS/ERS guidelines.37 Salbutamol 0.4 mg was the drug of choice for the bronchodilatation test in all study units. The main focus was on forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and percentage of FEV1 in FVC (FEV%), in order to observe possible obstruction and its reversibility (ie, asthma). Furthermore, peak expiratory flow and mean forced expiratory flow at 50% of the FVC (FEF50), and their reversibility, were taken into the analysis.

The preparticipation screening, performed by a physician, included normal clinical investigation and also several previously well-documented static and dynamic posture, movement control and musculoskeletal balance tests (table 2, see online supplementary appendix 1). Also, a structured examination protocol for recording current and previous apophyseal injuries such as Osgood-Schlatter's disease39 was used. Contents and protocol were adjusted and pre-tested in two separate sessions with two study physicians (HS and JP) and voluntary adolescents. After these sessions, all study physicians participated for a 1 day session, where tests and measurements were introduced and training was given.

Table 2.

Domains and contents of the preparticipation screening performed by a physician

| Domain | Contents* |

|---|---|

| Personal medical history |

|

| Posture |

|

| Range of motion |

|

| Core and knee control |

|

| Heart r auscultation (supine and sitting) | |

| Lung auscultation (normal and forced breathing) | |

| Palpation |

|

| Biological age evaluation (stage of maturity) |

|

| Skin inspection |

|

| Oropharyngeal inspection |

|

| Structured examination of different apophyses |

|

| Physical activity and sedentary behaviour |

|

*References in online supplementary appendix 1.

Statistical analyses

Normality of the data will be tested. Differences between categorical club-level and individual-level outcomes will be analysed using χ2 or Fisher's exact tests. Dichotomous versus continuous variables will be analysed using the conventional t tests and Mann-Whitney if the data is not normally distributed. An analysis of variance will be used to compare the differences between more than two groups. In addition, multilevel logistic regression will be used to analyse the associations between health promotion orientation, activity of the sports clubs and coaches, and health of the participants. Statistical analyses will be performed using SPSS V.20.0 statistical software.

Ethical issues

The HPSC study is carried out in conformance with the declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was received from the Ethics Committee of Health Care District of Central Finland (record number 23U/2012). All sports clubs participated in the study by free will. This was secured by requesting club permission at the beginning of the study. All respondents were notified that they had the right to refuse to participate and could withdraw from the study at any time.

The ethical statement required written consent from the participating youth for the questionnaire data, and written consent from a guardian and the adolescent him/herself for the preparticipation screening. All permission papers included detailed information of the study. The consent form for preparticipation screening, for example, consisted of five separate items: (1) approval for participation in the study and permission to use the information for research purposes, (2) permission for the information gathered in the surveys and preparticipation screening to be linked with existing nation-wide health registers, (3) permission for the blood samples to be saved and analysed during the next 15 years, (4) permission for the researchers to later contact the participant to ask if he/she would be interested in participating in a longitudinal study and (5) permission for the information gathered in the study to be used in international research collaboration.

The adolescents were notified that they had the right to refuse to participate and could withdraw their consent later without giving a reason. National and international standards and recommendations concerning research involving children and young people were followed. Specially trained staff members were responsible for the examinations and measurements, and measuring instruments were regularly calibrated. The personal data of the study participants are protected using code numbers. All research data will only be viewed and used by members of the research group, and they will not be distributed to outsiders. Data transfer and protection will be followed throughout the study, especially within the network. Proceedings of the study will be followed in Consortium Steering Group meetings, project group meetings and in daily communication.

Discussion

This paper describes the rationale and design of the national Health Promoting Sports Club study. The study design uses a cross-sectional multidisciplinary approach. A prospective cohort study is planned as the next phase of the study.

Combining the settings approach with leisure time PA

In health promotion, a settings-based approach has been developed in many environments, such as schools and workplaces, but less in those relating to leisure time.2 40 This HPSC research project corresponds to both preceding claims by illustrating, for the first time, nationally and internationally, and comprehensively with multiple approaches, the current situation of health promotion and injury prevention policies, and activities of the youth sports clubs and coaches; in regard to health behaviours and the health status of adolescents participating in sports club.

Comparison of club and individual-level variables/characteristics provides unique knowledge of the associations of club-based health promotion activity to coaches’ implementation activity, and further to health behaviours and status of adolescents participating in sports clubs. Furthermore, a unique aspect of this study is that youth participating in sports clubs are compared with their non-participating counterparts, not only using surveys, but also with objective PA measurement and preparticipation screenings.

Health promotion for youth participating in sports clubs is important from a perspective of athlete development, as there are many shortcomings in the health behaviours of young athletes, implying that more health and physical education also needs to be provided by sports clubs. Health promotion through sports clubs has several advantages when compared to that in formal educational settings. The most important factor is that the educational nature of the clubs, due to voluntary participation of the youth, is informal.8 The youth participate because they have an interest in a given sport, which provides a great opportunity to tailor health promotion to a particular sport and development, together with providing a more effective setting for health promotion.41 This, in turn, highlights a need for clubs to consider how to draw more people and/or other activities to start developing their concepts.

Good muscle balance is based on the control of posture, maintenance of adequate range of motion in joints and flexibility of muscles as well as good neural control of motion. Disturbances in posture and muscle balance can lead to increased overuse symptoms and a predisposition to injury.42 Additionally, these imbalances reduce the ability to perform good practice and weaken competition skills. In an assessment of posture and muscle balance, the main attention was focused on control and maintenance of the position of head, spine, shoulders and core, which include posture, alignment and control of the hip, knee, ankle and foot during stationary standing and motion. These variables can be modified by training and counselling, to prevent injuries.43 44

Asthma is a common disorder in children and adolescents, and undiagnosed and untreated asthma may prevent participation in normal PA in children.45 It is thus important to assess lung functions in connection with health screening. An asthma programme in Finland46 showed screening for asthma is effective in its diagnosis.

As expected, the results of this study clarify the current health promotion and injury prevention activity of Finnish youth sports clubs and generate a modern platform for improving the well-being of children and adolescents. At the same time, a protocol for and content of young sports club participants’ preparticipation screening and healthcare network will be further developed. This, in turn, will make it possible to standardise what a young sports club participant's preparticipation screening should consist of.

Challenges—real life research

There were many challenges to this multilevel research. First, although being positive, many sports clubs were unable to deliver the information needed, thus either clubs or study participants could not participate. This illustrates well the challenges faced when studying voluntary activity-based settings. People participate on their free time and of their own free will. The same is true under the coaches’ participation in the study, as about half failed to answer the questionnaire. It would be important for researchers and research projects to invest even more in motivating people to take part in the studies.

The age group of youth in the HPSC study was challenging in terms of participation. The same applies to the surveys and preparticipation screening. The survey via schools succeeded better than via sports clubs. The key factor is that the school-based survey was executed during a class and under supervision of a teacher. Despite using a web-based questionnaire, a postal-based invitation for sports club participants was not enough to get them to answer. For the preparticipation screenings, more sports club participants than non-participants, and more girls than boys, took part in the examinations. This reflects higher interest of these groups over the others. At the same time, this may have caused bias in the data, which needs to be acknowledged in the analyses.

In conclusion, this is the first time, to our knowledge, that sports clubs and coaches’ health promotion activities and health of youth participating in sports clubs compared to non-participants are simultaneously studied. The research project is close-to-practice, which generates foundations for development work for youth sports clubs to systematically execute health promotion, and recognise environmental and individual factors. At the same time, foundations for future intervention studies are created. The instruments created, used and validated can also be employed internationally and adapted to the school and working environment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the participating sports clubs and their officials and coaches. The authors also thank the participating schools for their assistance in the surveys. Without all the adolescents who participated in the study, especially those who took part in preparticipation screening, this research would not have been possible. The authors want to express our gratitude to these youth. The study involved many assistants. The authors wish to thank all of them, including study physicians: Maria Grannas, Harri Helajärvi, Timo Hänninen, Sergei Iljukov, Heikki Jokinen, Klaus Köhler, Jenni Leppävuori, Esa Liimatainen, Tuomas Mäkinen, Tiina Nylander and Rainer Rauramaa; clinical laboratory assistants: Ulla Hakala, Minna Hyppönen, Sirpa Hyyrönmäki, Hannu Kaikkonen, Riitta Koivula, Jarmo Lehtimäki, Tuula Tiihonen and Maria Uusimäki; and professor Ari Heinonen, for his valuable consultation in overall research design and quality of this article. The authors wish to express our gratitude to the funders of the study: the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture (major, grant number: 6/091/2011) and Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (minor, grant number: 152/THL/TE/2012). Finally, the authors wish to thank PhD student Sheree Bekker from the Federation University Australia for checking and revising the English language of the paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: SK and JP are the main contributors of the study, responsible for its conceptualisation and design. SK and JP are also main contributors to the manuscript. JP, HS, LA, OJH and KS are the physicians for the Centres of Excellence in Sports and Exercise Medicine, and RK is the chief researcher in Oulu; they have all contributed to the preparticipation screening, its design and realisation, and drafted the manuscript. UMK contributed to study design, including planning the clinical examinations, and revised the manuscript. TV is responsible for objective PA measurements and drafted the manuscript. LK contributed to health behaviour survey planning and execution, and drafted the manuscript. TA is the coordinator of the study and therefore contributed throughout the study, especially to its realisation, and drafted the manuscript. JV is expert in statistics and contributed to study sampling, data collection and analysing procedure throughout the study, and drafted the manuscript. All the authors have read the final manuscript and approved it.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee of Health Care District of Central Finland (record number 23U/2012).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Aira T, Kannas L, Tynjälä J et al. Liikunta-aktiivisuuden väheneminen murrosiässä. Drop off-ilmiön aikatrendejä ja kansainvälistä vertailua WHO-Koululaistutkimuksen (HBSC-Study) aineistoilla 1986–2010. Miksi murrosikäinen luopuu liikunnasta? [Diminishing Physical Activity in Adolecence. The Time Trends and International Comparisons of the Drop-off Phenomena in the 1986–2010 Data of Health Behavior in School-aged Children Study. In the publication Why adolescents give up on physical activity?]. Publications of State Council of Sport, 2013:12–29. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kokko S, Green LW, Kannas L. A review of settings-based health promotion with applications to sports clubs. Health Promot Int 2014;29:494–509. 10.1093/heapro/dat046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kokko S, Kannas L, Villberg J. The health promoting sports club in Finland—a challenge for the settings-based approach. Health Promot Int 2006;21:219–29. 10.1093/heapro/dal013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geidne S, Quennerstedt M, Eriksson C. The youth sports club as a health-promoting setting: an integrative review of research. Scand J Public Health 2013;41:269–83. 10.1177/1403494812473204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kokko S, Kannas L, Villberg J. Health promotion profile of youth sports clubs: club officials’ and coaches’ perceptions. Health Promot Int 2009;24:26–35. 10.1093/heapro/dan040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meganck J, Scheerder J, Thibaut E et al. Youth sports clubs’ potential as health-promoting setting: profiles, motives and barriers. Health Educ J 2015;74:531–43.. 10.1177/0017896914549486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Hoye A, Sarrazin P, Heuze JP et al. Coaches’ perceptions of French sport clubs: health promotion activities, aims, and coach motivation. Health Educ J 2015;74:231–43. 10.1177/0017896914531510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kokko S. Health Promoting Sports Club—Youth Sports Clubs’ Health Promotion Profiles, Guidance, and Associated Coaching Practice. Finland: University of Jyväskylä: Studies in Sport, Physical Activity and Health, 2010:144. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly B, Baur LA, Bauman AE et al. Health promotion in sport: An analysis of peak sporting organisations’ health policies. J Sci Med Sport 2010;13:566–7. 10.1016/j.jsams.2010.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casey MM, Payne WR, Eime RM et al. Organisational readiness and capacity building strategies of sporting organisations to promote health. Sport Manag Rev 2012;15:109–24. 10.1016/j.smr.2011.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liukkonen J, Jaakkola T, Kokko S et al. Results from Finland´s 2014 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. J Phys Act Health Suppl 2014;11:51–7. 10.1123/jpah.2014-0168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hakkarainen H, Härkönen A, Niemi-Nikkola K et al. eds. Selvitysraportti—Urheilevien lasten ja nuorten fyysis-motorinen harjoittelu. [Report—The physic-motor training of children and adolescents. Helsinki: SLU-paino, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eiosdottir SP, Kristjansson AL, Sigfusdottir ID et al. Trends in physical activity and participation in sports clubs among Icelandic adolescents. Eur J Public Health 2008;18:289–93. 10.1093/eurpub/ckn004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kokko S, Villberg J, Kannas L. Nuori urheilijan polulla—13–15 -vuotiaiden urheilijoiden arvioita harjoitusmääristään, harjoittelun monipuolisuudesta sekä elämäntavoista. [Youth on the athlete track—the evaluation of 13 to 15 years old athletes on their training volume, versatility and lifestyle]. Helsinki: Young Finland Association, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haukkala A, Vartiainen E, de Vries H. Progression of oral snuff use among Finnish 13–16-year-old students and its relation to smoking behaviour. Addiction 2006;101:581–9. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01346.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melnick MJ, Miller KE, Sabo DF et al. Tobacco use among high school athletes and nonathletes: Results of the 1997 youth risk behavior survey. Adolescence 2001;36:727–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kannas L, Vuori M, Seppälä H-R et al. Suojaako urheiluseuratoiminta nuoria päihteiltä ja tupakalta. [Do the sports club's activities protect from intoxicants and tobacco]. Liikunta Tiede 2002;39:4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rolandsson M, Hugoson A. Factors associated with snuffing habits among ice-hockey-playing boys. Swed Dent J 2001;25:145–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun H, Koehler K, Geyer H et al. Dietary supplement use among elite young German athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc 2009;19:97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dickinson B, Goldberg L, Elliot D et al. Hormone abuse in adolescents and adults—a review of current knowledge. Endocrinologist 2005;15:115–25. 10.1097/01.ten.0000157881.51030.b4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oja P, Titze S, Kokko S et al. Health benefits of different sport disciplines: systematic review of observational and intervention studies with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:434–40. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parkkari J, Kannus P, Natri A et al. Active living and injury risk. A prospective one-year follow-up of a population cohort comparing the injury risk in various commuting and lifestyle activities, and recreational and competitive sports. Int J Sports Med 2004;25:209–16. 10.1055/s-2004-819935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parkkari J, Pasanen K, Mattila V et al. The risk for a cruciate ligament injury of the knee in adolescents and young adults. a population-based cohort study of 46,500 persons with 9-year follow-up. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:422–6. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.046185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernelahti M, Heinonen OJ, Karjalainen J et al. Sudden cardiac death in young athletes: time for a Nordic approach in screening? Scand J Med Sci Sports 2008;18:132–9. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00749.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helenius IJ, Tikkanen HO, Sarna S et al. Asthma and increased bronchial responsiveness in elite athletes: atopy and sport event as risk factor. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998;101:646–52. 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70173-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Päivinen MK, Keskinen KL, Tikkanen HO. Swimming and asthma: factors underlying respiratory symptoms in competitive swimmers. Clin Respir J 2010;4:97–103. 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2009.00155.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck KC. Evaluating exercise capacity and lung function in the athlete. In: Weiler JM, ed. Allergic and respiratory disease in sports medicine. New York: Mercel Dekker, 1997:35–64. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kokko S, Kannas L, Villberg J et al. Health promotion guidance activity of youth sports clubs. Health Educ 2011;111:452–63. 10.1108/09654281111180454 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kokko S, Villberg J, Kannas L. Health promotion in sport coaching: coaches and young male athletes’ evaluations on the health promotion activity of coaches. Int J Sport Sci Coaching 2015;10:339–52. 10.1260/1747-9541.10.2-3.339 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kannas L. ed. Koululaisten terveys ja terveyskäyttäytyminen muutoksessa. WHO-Koululaistutkimus 20 vuotta. [The health and health behaviors of school-aged children in change. Health behavior in school-aged children study 20 years]. University of Jyväskylä: Publications of Research Center for Health Promotion, 2004;2. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alaranta A. Medication use in Elite Athletes. University of Helsinki: Yliopistopaino, 2006:13. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pasanen K, Parkkari J, Pasanen M et al. Neuromuscular training and the risk of leg injuries in female floorball players: cluster randomised controlled study. BMJ 2008;337:96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ristolainen L, Heinonen A, Turunen H et al. Type of sport is related to injury profile: a study on cross country skiers, swimmers, long-distance runners and soccer players. A retrospective 12-month study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010;20:384–93. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00955.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al., Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals. Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension 2005;45:142–61. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asmar R, Safar M, Queneau P. Pulse pressure: an important tool in cardiovascular pharmacology and therapeutics. Drugs 2003;63:927–32. 10.2165/00003495-200363100-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorodeski EZ, Ishwaran H, Blackstone EH et al. Quantitative electrocardiographic measures and long-term mortality in exercise test patients with clinically normal resting electrocardiograms. Am Heart J 2009;158:61–70. 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V et al. ATS/ERS task force: standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38. 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viljanen AA, Halttunen PK, Kreus KE et al. Spirometric studies in non-smoking, healthy adults. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl 1982;159:5–20. 10.1080/00365518209168377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kujala UM, Kvist M, Heinonen O. Osgood-Schlatter's disease in adolescent athletes. Retrospective study of incidence and duration. Am J Sports Med 1985;13:236–41. 10.1177/036354658501300404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Golden SD, Earp JA. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: twenty years of Health Education & Behavior health promotion interventions. Health Educ Behav 2012;39:364–72. 10.1177/1090198111418634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kokko S. Sports clubs as settings for health promotion: Fundamentals and an overview to research. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2014;42:60–5. 10.1177/1403494814545105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verrelst R, Willems TM, De Clercq D et al. The role of hip abductor and external rotator muscle strength in the development of exertional medial tibial pain: a prospective study. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1564–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leppänen M, Aaltonen S, Parkkari J et al. Interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sports Med 2014;44:473–86. 10.1007/s40279-013-0136-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parkkari J, Taanila H, Suni J et al. Neuromuscular training with injury prevention counselling to decrease the risk of acute musculoskeletal injury in young men during military service: a population-based randomized study. BMC Med 2011;9:35 10.1186/1741-7015-9-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams B, Powell A, Hoskins G et al. Exploring and explaining low participation in physical activity among children and young people with asthma: a review. BMC Fam Pract 2008;9:40 10.1186/1471-2296-9-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haahtela T, Tuomisto LE, Pietinalho A et al. A 10 year asthma programme in Finland: major change for the better. Thorax 2006;61:663–70. 10.1136/thx.2005.055699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.