Abstract

Background/aim

To address the question as to whether immersion pulmonary oedema (IPO) may be a common cause of death in triathlons, markers of swimming-induced pulmonary oedema (SIPO) susceptibility were sought in triathletes' postmortem examinations.

Methods

Deaths while training for or during triathlon events in the USA and Canada from October 2008 to November 2015 were identified, and postmortem reports requested. We assessed obvious causes of death; the prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH); comparison with healthy triathletes.

Results

We identified 58 deaths during the time period of the review, 42 (72.4%) of which occurred during a swim. Of these, 23 postmortem reports were obtained. Five individuals had significant (≥70%) coronary artery narrowing; one each had coronary stents; retroperitoneal haemorrhage; or aortic dissection. 9 of 20 (45%) with reported heart mass exceeded 95th centile values. LV free wall and septal thickness were reported in 14 and 9 cases, respectively; of these, 6 (42.9%) and 4 (44.4%) cases exceeded normal values. 6 of 15 individuals (40%) without an obvious cause of death had excessive heart mass. The proportion of individuals with LVH exceeded the prevalence in the general triathlete population.

Conclusions

LVH—a marker of SIPO susceptibility—was present in a greater than the expected proportion of triathletes who died during the swim portion. We propose that IPO may be a significant aetiology of death during the swimming phase in triathletes. The importance of testing for LVH in triathletes as a predictor of adverse outcomes should be explored further.

Keywords: Death, Swimming, Triathlon, Pulmonary

What are the new findings?

In a series of deaths occurring during the swim portion of triathlon events, a high proportion of autopsies demonstrated cardiac anomalies, in particular left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). LVH is a marker of immersion pulmonary oedema (IPO) susceptibility, and the authors propose that many of these deaths were due to swimming-induced pulmonary oedema (SIPO).

How might it impact on clinical practice in the near future?

The results suggest that screening examinations for triathletes should search for conditions that predispose to SIPO, such as hypertension, LVH and obstructive sleep apnoea. A risk reduction strategy that may prevent some of these deaths should include optimisation of blood pressure and body weight, and treatment of sleep apnoea.

Introduction

The triathlon is a sequence of consecutive races consisting of a sequence of swim (750–3800 m), bicycle (13–112 km) and foot (5–42 km) races. As in all competitive sports, there is a modest sudden death rate, which has been estimated at 1.5 per 100 000 participants,1 in sanctioned triathlon events, two to three times greater than the marathon rate.2 3 As most deaths occur during the swim when the victim's plight is not readily distinguishable among the large number of swimmers, the proximate cause of sudden death in the swim portion of the triathlon remains elusive.

Drowning, the process of experiencing respiratory impairment from submersion/immersion in liquid,4 is often the official reported cause of swimming death;1 however, drowning seems unlikely in experienced swimmers. Predictors of cardiac death—the overwhelming primary cause of sudden death in most other sports2 5–8—remain elusive in triathletes. Arrhythmic causes, including prolonged QTc and autonomic conflict (simultaneous activation of sympathetic and parasympathetic),4 9 have been proposed in triathlete cardiac death. Other suggested causes include exertional heat stroke, myocardial infarction, head trauma, panic attack and arrhythmia.10 Cause of death uncommonly can be attributed to an anatomic cardiac anomaly;1 thus, in most cases, physiological causes must be sought.

Immersion pulmonary oedema (IPO, also known as swimming-induced pulmonary oedema, SIPO) is one such potential cause. IPO presents as rapid onset of dyspnoea, wheezing, hypoxaemia and expectoration of blood-tinged sputum, which can incapacitate a swimmer. A recent comprehensive review of swimming-related death identified IPO as a possible cause.11 Although IPO usually occurs in healthy individuals without an obvious predisposing factor, many victims have left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), hypertension and other cardiovascular comorbidities—potential markers of susceptibility.12–15

The current investigation was performed to test the hypothesis that, when compared with healthy triathletes and the general population, individuals who died during a triathlon or in training have a higher prevalence of cardiac anomalies that could predispose to IPO.

Methods

The study was approved by the Duke Medicine Institutional Review Board. Using the search phrase ‘triathlon death’, deaths during triathlon events or while in training for triathlons in the USA and Canada from October 2008 to November 2015 were identified using manual internet searches and Google Alerts. The phase of the event when death occurred was obtained from news sources such as newspaper articles or internet postings. Medical examiner reports for those participants who died during a swim were requested, and the phase of the race in which each acute event occurred was confirmed from the report.

Each medical examiner report was examined to determine whether there were any abnormalities of coronary arteries, cardiac muscle or valves, or obvious cause of death other than coronary disease. Heart mass and myocardial thickness were recorded. Heart mass was classified relative to normal reference ranges: for men 233–383 g;16 for women 148–296 g.17 Heart mass and ventricular wall thickness were also compared with the 95th centile values of normal heart mass scaled to height and sex.18 Values also were compared with echocardiographic data obtained from a population of triathletes.19 Also recorded were age, sex, height, body mass, body mass index, event date, death date, autopsy results and any other available pertinent information. Significant coronary artery disease (CAD) was enumerated as ≥70%; ≥50% coronary narrowing was also recorded.20 LV mass was conservatively estimated as 75% of total heart weight.21

Statistical comparisons of categorical variables were performed using χ2 test or Fisher's exact test (JMP Pro V. 12.1.0: SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

We identified 58 deaths during the time period of the review, of which 42 (72.4%) occurred during the swim (tables 1 and 2). A total of 23 medical examiner reports were obtained and reviewed. There were 19 men and 4 women (table 3). The age distribution of the population of individuals for whom medical examiner report was available did not differ from the total population of swimming deaths (table 4, χ2=1.274, p=0.74). Further details are provided in table 5 and the online supplementary file.

Table 1.

Distribution of sex and age (years) in all recorded triathlon deaths

| Males | Females | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 49 | 9 | 58 |

| Mean (SD) | 49.5 (11.8) | 41.8 (7.0) | 48.3 (11.5) |

| Range | 28–76 | 31–54 | 28–76 |

Table 2.

Activity in which death occurred

| Activity | Death during training N (%) |

Death during event N (%) |

Total deaths N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swim | 3 (30) | 39 (81.3) | 42 (72.4) |

| Bike | 5 (50) | 6 (12.5) | 11 (19.0) |

| Run | 2 (20) | 3 (6.3) | 5 (8.6) |

| Total | 10 (100.0) | 48 (100.0) | 58 (100.0) |

Table 3.

Sex distribution of all swimming deaths and deaths for which medical examiner report was available

| Sex | All swimming deaths N (%) |

Autopsied deaths N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 36 (85.7) | 19 (82.6) |

| Female | 6 (14.3) | 4 (17.4) |

| Total | 42 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) |

Table 4.

Age distribution of all swimming deaths and deaths for which medical examiner report was available

| Age range | All swimming deaths N (%) |

Swimming deaths with medical examiner report N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| <40 | 4 (9.5) | 2 (8.7) |

| 40–49 | 16 (38.1) | 12 (52.2) |

| 50–59 | 13 (31.0) | 5 (21.7) |

| ≥60 | 9 (21.4) | 4 (17.4) |

| Total | 42 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) |

Table 5.

Summary of cases with medical examiner report

| Categories | N | Age Mean (SD), range (years) |

Height Mean (SD), range (months) |

Weight Mean (SD), range (kg) |

BMI Mean (SD), range (kg/m2) |

Heart mass Mean (SD), range (g) |

Heart mass Greater than normal* |

CAD: ≥70% narrowing in any coronary artery20 | CAD: ≥50% narrowing in any coronary artery20 | RV thickness† Mean (SD), range (mm), N |

LV thickness† Mean (SD), range (mm), N |

Septal thickness† Mean (SD), range (mm), N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 23 | 49.5 (9.6), 33–68 | 1.77 (0.07), 1.63–1.93 | 96.2 (32.1), 51.7–199.6 |

30.9 (11.7), 15.9–75.5 |

447.6 (82.7), 290–630 | 20/21 (95.2%) | 5/22 (22.7%) | 7/22 (31.8%) | 4.0 (1.6), 2–8, N=12 | 14.6 (5.2), 10–26, N=14 | 15.7 (6.5), 8–26, N=9 |

| White | 21 | |||||||||||

| Male | 18 | 51.6 (9.9), 33–68 | 1.80 (0.05), 1.70–1.93 | 95.8 (20.5), 69.7–142.5 |

29.5 (4.8), 23.4–38.3 |

462.4 (77.0), 290–630 |

14/15 (93.3%) | 5/17 (29.4%)‡ | 7/17 (41.2%)‡ | 5.5 (2.1), 3–8, N=10 | 18.3 (8.4), 10–26, N=11 | 13.0 (18.4), 10–26, N=7 |

| Female | 3 | 40.3 (2.5), 38–43 | 1.71 (0.08), 1.65–1.80) | 71.4 (17.4), 51.7–84.8 |

24.9 (8.0), 15.9–31.1 |

363.7 (92.1), 310–470 |

3/3 (100%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 2.5 (0.7), 2–3, N=2 | 12.7 (3.8), 10–17, N=3 | 8.5 (0.7), 8–9, N=2 |

| Black | 2 | |||||||||||

| Male | 1 | 45.0 (0.0), NA | 1.73 (0.0), NA | 74.4 (0.0), NA | 24.9 (0.0), NA | 400.0 (0.0), NA | 1/1 (100%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | NR | NR | NR |

| Female | 1 | 44.0 (0.0), NA | 1.63 (0.0), NA | 199.6 (0.0), NA | 75.5 (0.0), NA | 510 (0.0), NA | 1/1 (100%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | NR | NR | NR |

†Myocardial thickness was not consistently reported. Where it was reported as a range, the average value was used.

‡One individual did not have an autopsy but was known to have coronary artery stents and was counted as having ≥70% coronary artery narrowing.BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; LV, left ventricle; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; RV, right ventricle.

bmjsem-2016-000146supp.pdf (87.5KB, pdf)

Among the population of swimming deaths, the age distribution in individuals for whom medical examiner report was available did not differ from the total population of swimming deaths (p=0.73, Fisher's exact test).

Four individuals had significant (≥70%) CAD. A man aged 58 years died of a massive retroperitoneal haemorrhage due to renal artery dissection. Death was attributed to acute dissection of the descending aorta in a man aged 66 years. A man aged 46 years had a history of atrial fibrillation, and flecainide was detected in his urine. A man aged 68 years was known to have coronary stents; his death was presumed to have been due to coronary disease and a full autopsy was not performed. Post-resuscitation ECG revealed prolonged QTc interval in a man aged 44 years whose initial cardiac rhythm was ventricular fibrillation. A woman aged 38 years had acute myocarditis. All individuals had pulmonary oedema.

Of 20 with reported heart mass and height, 9 (45%) exceeded 95th centile values based on height.18 LV free wall thickness was reported in 14 cases, and exceeded 95th centile (1.49 cm) in 6 (42.9%); septal thickness was reported in 9 cases, and exceeded 95th centile (1.69 cm) in 4 (44.4%).

Excluding those with an obvious possible cause of death (coronary disease ≥70% narrowing (n=4), presumed coronary disease due to history of stent placement (n=1), retroperitoneal haemorrhage (n=1), aortic dissection (n=1)), 16 individuals remained. Of these, 6 (37.5%) had excessive heart mass, one of whom also had acute myocarditis. In this group, there was a higher proportion of individuals with thickened LV compared with the general triathlete population (p<0.001, table 6).

Table 6.

Cardiac morphology in current series compared with echocardiographic data in 225 triathletes studied by Douglas19

| Criterion for LVH | Per cent, Douglas, 199719 | Per cent, current series (all cases) | p Value | Per cent, current series (CAD, haemorrhage, aortic dissection excluded) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart mass > threshold* | 24 | 45 (N=20) | 0.023 | 37.5 (N=16) | 0.1 |

| Septum ≥1.3 cm | 1 | 67 (N=9) | <0.001 | 66.7 (N=6) | <0.001 |

| Posterior wall ≥1.3 cm | 0.5 | 50 (N=14) | <0.001 | 50 (N=10) | <0.001 |

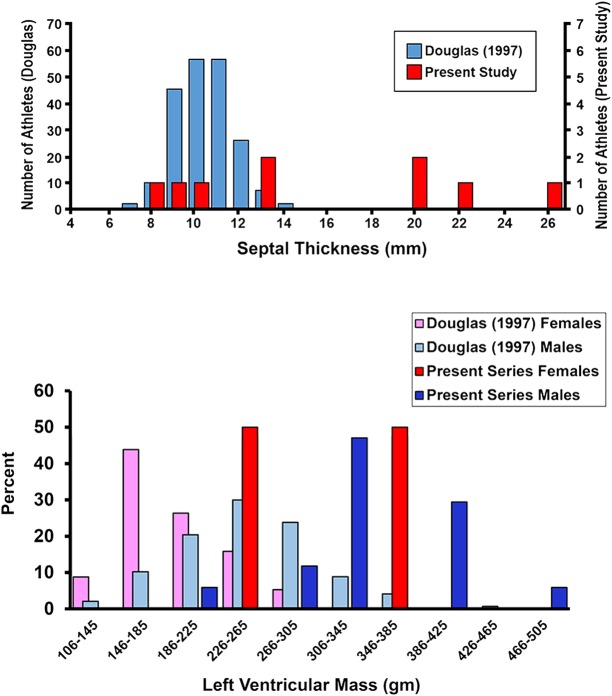

The distributions of LV mass and septal thickness are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Above: septal thickness from an echocardiographic study of participants in the Hawaii Ironman Triathlon19 and the present autopsy series; below: left ventricular mass reported by Douglas and estimated as 75% of heart weight at autopsy.21

Discussion

Albeit the probability of death during a triathlon is low, when occurring in a highly publicised event it inevitably raises a great deal of public concern about the sport's safety. This impelled the largest North American triathlon organisation to initiate an inquiry into triathlon deaths.22 23 Unfortunately, good data are difficult to obtain and hence specific screening or aftercare recommendations could not be made. The current investigation was performed to test the hypothesis that, when compared with triathletes and the general population, individuals who died swimming during a triathlon or in training have a higher prevalence of cardiac anomalies that predispose to IPO.

IPO and its causes

Water immersion causes blood redistribution from the periphery to the heart and pulmonary vessels, causing an increase in central blood volume and pulmonary vascular pressures.24 This can be extreme and precipitate pulmonary oedema in IPO-susceptible individuals, even in those without any obvious comorbidities.25 The effect is augmented—especially during exercise—in cold versus warm water.26 Those triathletes susceptible to IPO are therefore believed to have abnormal myocardial diastolic compliance (lusitropy)—or stiff hearts. Abnormal LV diastolic compliance is partly responsible for elevated LV end-diastolic pressure during exercise in patients suffering from heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).27 IPO seems to be a form of HFpEF precipitated by increased preload due to immersion with heavy exertion. In the initial publication of IPO, a number of individuals exhibited a hypertensive response to cold exposure; thus, it is plausible that they had LVH.12 In a recent review of published cases, nearly 50% of published civilian IPO cases had identifiable predisposing factors, and most were cardiac.15 The association of IPO susceptibility with LVH and risk factors for LVH12–15 strongly implicates abnormal LV diastolic compliance.

Since most sudden deaths occur during the swim portion of the triathlon, it is certainly plausible that IPO is a cause. IPO tends to occur in susceptible individuals most frequently in cold water, and often during heavy exertion.12 28–30 Typical IPO symptoms—cough productive of pink frothy or blood-tinged secretions occurring during a swim—have been reported by 1.4% of triathletes,31 and in 1.8–60% during 2.4–3.6 km open sea swimming trials in young, fit naval recruits.29 32

The prevalence of LVH in the general population is estimated to be 12–21%.33 34 In well-trained triathletes, LV dimensions are usually within the normal range for the general population.19 35 36 In a group of 235 triathletes (168 men, 67 women) participating in the Hawaii Ironman Triathlon from 1985 to 1995, the overall prevalence of LVH by echocardiography was 24% (LV mass >294 g in men, >198 g in women).19 Chronic, high-intensity exercise can also lead to LVH (athlete's heart); this was the most likely cause of the enlarged LV in most cases in the quoted series. Diastolic filling properties in athlete's heart under dry, resting conditions are normal;37 38 thus, it is unlikely that athlete's heart is a precipitating cause of IPO. LV thickness in athlete's heart very rarely exceeds 13 mm.39 40 In contrast, in the current series, a pathological cause of enlarged hearts was more prevalent, including extreme values of septal thickness and estimated LV mass (figure 1), significantly beyond the range expected from hypertrophy due to athlete's heart.36 39 41 Thus, diastolic filling properties were more likely to be abnormal. All autopsied cases in this series had pulmonary oedema, which is usually the end result from any attempt at cardiopulmonary resuscitation and water aspiration during terminal event. Thus, the existence of pulmonary oedema at autopsy provides little insight.

Possible causes of death in triathlons

In some cases, cardiac anatomy at autopsy after a triathlon may occasionally provide clues to the cause of death.1 Of nine athletes autopsied after a triathlon-related death, only two had cardiac anomalies that could be construed as being a primary cause of death: one with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, the other with a congenital coronary artery anomaly. On the other hand, six had LVH.1

IPO is a plausible cause of triathlon death, particularly since it has been suggested as one possible mechanism in the pathophysiology of drowning.4 In contrast, due to the rarity of IPO-related deaths and lack of known history of IPO in any triathlon death, some have concluded that it is an unlikely cause of death in triathletes.10 22 23 Nevertheless, several IPO-related deaths have been reported in other settings.42–47 Fatal cases of IPO may be rare but probably under-recognised; unless an episode is witnessed and survival is sufficiently long enough to obtain adequate clinical information to make the diagnosis, attribution of an in-water death to IPO is exceedingly difficult.48

It is impossible to exclude primary arrhythmia as the cause of death in these individuals. Indeed, it has been proposed that cardiomegaly is an independent risk factor for cardiac arrhythmia.35 49–51 However, in a series of cardiac arrests during long-distance runs (where diagnostic facilities are more likely to be available and thus early detection of an arrhythmia more likely), primary arrhythmia was the purported cause in only a minority of instances. Non-ischaemic ventricular tachycardia was observed in only 7%, with ‘presumed arrhythmia’ the attributed cause in an additional 7%.3 One individual in our series had a history of atrial fibrillation and was taking an antiarrhythmic. It is not possible to know whether his propensity towards atrial arrhythmias contributed to his death; however, any rhythm other than sinus rhythm is likely to cause a rise in pulmonary artery and capillary pressures in the face of increased preload as occurs during immersion. In fact, atrial fibrillation has been proposed as a predisposing condition for IPO.52 In another case in the present series, prolonged QTc was noted after resuscitation. Swimming can be a trigger for arrhythmias in long QTc syndrome;53 however, prolonged QTc could also be secondary to antiarrhythmic drug administration after cardiopulmonary resuscitation or the cardiac injury itself. Information about genetic predisposition was unavailable. On the other hand, additional information from bystanders and others suggests that at least some of the deaths in the current series were not sudden and had features consistent with IPO (eg, cases 2, 10, 23 in the online supplementary material).

It might also be argued that demand ischaemia might be more likely during swimming, even in those with minimal coronary narrowing, because of the central redistribution of blood and higher LV volume. For a given level of exercise, this might lead to greater myocardial wall tension and myocardial oxygen consumption compared to dry land. However, in patients with known CAD, a study of swimming in cold water versus cycling demonstrated that ST segment depression occurred at similar levels of exercise during both activities.54

The distribution of cardiac pathologies in this series is in marked contrast with other similar studies: in younger cohorts of sudden death cases, myocarditis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and coronary artery abnormalities are more common.55 In case series with age distribution similar to the current series, atherosclerotic disease predominates.56 57 Of those in our cohort in whom coronary arteries were mentioned in the medical examiner's report, only four individuals had ≥70% coronary narrowing; six individuals had ≥50% narrowing. One additional person who did not have an autopsy but had coronary artery stents was presumed to have ≥50% narrowing. Whereas HCM is a common cause of sudden cardiac death in most series of land-based athletic events, no mention of it was made in any of the medical examiner reports in this series. While it can be difficult to distinguish HCM from undifferentiated LVH at autopsy,58 the apparent lack of HCM in this series is consistent with the physiology of swimming: blood redistribution during immersion dilates the LV and thus reduces the likelihood of LV outflow obstruction even when present.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study showing that markers of IPO susceptibility are common among victims of sudden death during triathlons. It cannot be definitively concluded that the cause of death in individuals with LVH was IPO. IPO has been considered by some to be an unlikely cause of triathlon death due to lack of prior history among victims. However, instances of IPO are most likely under-reported. Most triathletes train for the swim portion in pools, which are generally warmer than open bodies of water where events are held, and during a pool swim mild IPO symptoms can be relieved at an early stage by exiting the water. Primary arrhythmias cannot be excluded; indeed, it has been suggested that arrhythmias are more common among individuals with LVH.34

Among those classified as having no obvious cause of death, one (woman aged 38 years, see online supplementary case 3) had histologic evidence for acute myocarditis. Two others (man aged 57 years, see online supplementary case 6 and man aged 48 years, see online supplementary case 18) had 50–60% coronary stenosis. Although this degree of stenosis is not conventionally considered to be critical, the true degree of narrowing could have been underestimated at autopsy. Another (man aged 46 years, see online supplementary case 10) had no CAD but did have areas of myocardial fibrosis and chronic inflammation suggesting remote infarction. Finally, one case (man aged 43 years, see online supplementary case 12) had scattered intramural adipose and focal loose interstitial fibrous tissue. Although not identified as such by the examining pathologist, this could be consistent with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. We cannot exclude the possibility that these individuals might have died of an arrhythmia.

While there could be inconsistencies in attempting to compare LVH using echocardiography with heart mass determined at autopsy (table 6), we feel that gross errors are unlikely as echo has been validated against postmortem measurements.59

Among 775 sports-related sudden death cases during moderate-to-vigorous exertion among men and women, fewer deaths occur during swimming than cycling or jogging.60 This could be a consequence, in individuals at risk for athletic sudden death, of fewer person-hours spent swimming. However, in triathlons, a specific swimming-related mechanism for death would be expected to predominate where swimming is the first of three events.

Nevertheless, observations demonstrating that IPO is relatively common in competitive swimming such as military training and triathlons—and has been the cause of deaths42–47—implicate this condition as a likely cause of at least some deaths in triathlons. It would have been ideal to compare autopsies of triathletes dying during the bicycle or run portions; however, this was not possible due to fewer of those deaths, with a significant proportion due to motor vehicle trauma. Interestingly, scuba diving is another precipitating activity for IPO; indeed, LVH has been observed in a high percentage of scuba diving deaths.61

Conclusion

In a series of sudden deaths occurring during triathlon training or events, we found evidence on postmortem examination of a prevalence of IPO susceptibility markers (LVH) in excess of the prevalence expected among healthy triathletes. We suspect that IPO may be a significant cause of death in triathletes. Analogous to the management of HFpEF, the goal should be to seek and eliminate pertinent risk factors such as hypertension, obesity and obstructive sleep apnoea.62 Educational programmes to promulgate information about risk factors could raise awareness and reduce the risk in this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the numerous medical examiners' offices that provided the reports.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Richard Moon at @RichardEMoon

Contributors: REM initiated the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. SDM assisted with data collection and manuscript editing. DFP assisted with data analysis. WEK provided expert input and edited the manuscript.

Funding: US Naval Sea Systems Command N0463A-07-C-0002 and N61331-03-C-0015.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Duke Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Harris KM, Henry JT, Rohman E et al. Sudden death during the triathlon. JAMA 2010;303:1255–7. 10.1001/jama.2010.368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redelmeier DA, Greenwald JA. Competing risks of mortality with marathons: retrospective analysis. BMJ 2007;335:1275–7. 10.1136/bmj.39384.551539.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JH, Malhotra R, Chiampas G et al. Cardiac arrest during long-distance running races. N Engl J Med 2012;366:130–40. 10.1056/NEJMoa1106468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bierens JJ, Lunetta P, Tipton M et al. Physiology of drowning: a review. Physiology (Bethesda) 2016;31:147–66. 10.1152/physiol.00002.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maron BJ. Sudden death in young athletes. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1064–75. 10.1056/NEJMra022783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tunstall Pedoe DS. Marathon cardiac deaths : the London experience. Sports Med 2007;37:448–50. 10.2165/00007256-200737040-00046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marijon E, Tafflet M, Celermajer DS et al. Sports-related sudden death in the general population. Circulation 2011;124:672–81. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.008979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toukola T, Hookana E, Junttila J et al. Sudden cardiac death during physical exercise: characteristics of victims and autopsy findings. Ann Med 2015;47:263–8. 10.3109/07853890.2015.1025824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tipton MJ. Sudden cardiac death during open water swimming. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1134–5. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eichner ER. The mystery of swimming deaths in athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep 2011;10:3–4. 10.1249/JSR.0b013e318205e0f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asplund CA, Creswell LL. Hypothesised mechanisms of swimming-related death: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. Published Online First: 3 Mar 2016. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilmshurst PT, Nuri M, Crowther A et al. Cold-induced pulmonary oedema in scuba divers and swimmers and subsequent development of hypertension. Lancet 1989;1:62–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)91426-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gempp E, Louge P, Henckes A et al. Reversible myocardial dysfunction and clinical outcome in scuba divers with immersion pulmonary edema. Am J Cardiol 2013;111:1655–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.01.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gempp E, Demaistre S, Louge P. Hypertension is predictive of recurrent immersion pulmonary edema in scuba divers. Int J Cardiol 2014;172:528–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peacher DF, Martina SD, Otteni CE et al. Immersion pulmonary edema and comorbidities: case series and updated review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2015;47:1128–34. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molina DK, DiMaio VJ. Normal organ weights in men: part I-the heart. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2012;33:362–7. 10.1097/PAF.0b013e31823d298b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molina DK, DiMaio VJ. Normal organ weights in Women: part I-The Heart. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2015;36:176–81. 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitzman DW, Scholz DG, Hagen PT et al. Age-related changes in normal human hearts during the first 10 decades of life. Part II (Maturity): a quantitative anatomic study of 765 specimens from subjects 20 to 99 years old. Mayo Clin Proc 1988;63:137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douglas PS, O'Toole ML, Katz SE et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy in athletes. Am J Cardiol 1997;80:1384–8. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00693-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipinski M, Do D, Morise A et al. What percent luminal stenosis should be used to define angiographic coronary artery disease for noninvasive test evaluation? Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2002;7:98–105. 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2002.tb00149.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy ML, White HJ, Meade J et al. The relationship between hypertrophy and dilatation in the postmortem heart. Clin Cardiol 1988;11:297–302. 10.1002/clc.4960110505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medical Panel Report. USA triathlon fatality incidents study. 2012 edn USA: Triathlon, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dressendorfer R. Triathlon swim deaths. Curr Sports Med Rep 2015;14:151–2. 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arborelius M Jr, Ballidin UI, Lilja B et al. Hemodynamic changes in man during immersion with the head above water. Aerosp Med 1972;43:592–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moon RE, Martina SD, Peacher DF et al. Swimming-induced pulmonary edema: pathophysiology and risk reduction with sildenafil. Circulation 2016;133:988–96. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wester TE, Cherry AD, Pollock NW et al. Effects of head and body cooling on hemodynamics during immersed prone exercise at 1 ATA. J Appl Physiol 2009;106:691–700. 10.1152/japplphysiol.91237.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borlaug BA, Jaber WA, Ommen SR et al. Diastolic relaxation and compliance reserve during dynamic exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart 2011;97:964–9. 10.1136/hrt.2010.212787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hampson NB, Dunford RG. Pulmonary edema of scuba divers. Undersea Hyperb Med 1997;24:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adir Y, Shupak A, Gil A et al. Swimming-induced pulmonary edema: clinical presentation and serial lung function. Chest 2004;126:394–9. 10.1378/chest.126.2.394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koehle MS, Lepawsky M, McKenzie DC. Pulmonary oedema of immersion. Sports Med 2005;35:183–90. 10.2165/00007256-200535030-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller CC 3rd, Calder-Becker K, Modave F. Swimming-induced pulmonary edema in triathletes. Am J Emerg Med 2010;28:941–6. 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shupak A, Weiler-Ravell D, Adir Y et al. Pulmonary oedema induced by strenuous swimming: a field study. Respir Physiol 2000;121:25–31. 10.1016/S0034-5687(00)00109-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levy D, Savage DD, Garrison RJ et al. Echocardiographic criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy: the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Cardiol 1987;59:956–60. 10.1016/0002-9149(87)91133-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laukkanen JA, Khan H, Kurl S et al. Left ventricular mass and the risk of sudden cardiac death: a population-based study. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e001285 10.1161/JAHA.114.001285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Claessens P, Claessens C, Claessens M et al. Ventricular premature beats in triathletes: still a physiological phenomenon? Cardiology 1999;92:28–38. doi:6943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whyte GP, George K, Sharma S et al. The upper limit of physiological cardiac hypertrophy in elite male and female athletes: the British experience. Eur J Appl Physiol 2004;92:592–7. 10.1007/s00421-004-1052-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colan SD, Sanders SP, MacPherson D et al. Left ventricular diastolic function in elite athletes with physiologic cardiac hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985;6:545–9. 10.1016/S0735-1097(85)80111-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simsek Z, Hakan Tas M, Degirmenci H et al. Speckle tracking echocardiographic analysis of left ventricular systolic and diastolic functions of young elite athletes with eccentric and concentric type of cardiac remodeling. Echocardiography 2013;30:1202–8. 10.1111/echo.12263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pelliccia A, Maron BJ, Spataro A et al. The upper limit of physiologic cardiac hypertrophy in highly trained elite athletes. N Engl J Med 1991;324:295–301. 10.1056/NEJM199101313240504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maron BJ, Pelliccia A, Spirito P. Cardiac disease in young trained athletes. Insights into methods for distinguishing athlete's heart from structural heart disease, with particular emphasis on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1995;91:1596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caselli S, Di Paolo FM, Pisicchio C et al. Three-dimensional echocardiographic characterization of left ventricular remodeling in Olympic athletes. Am J Cardiol 2011;108:141–7. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.02.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cochard G, Arvieux J, Lacour JM et al. Pulmonary edema in scuba divers: recurrence and fatal outcome. Undersea Hyperb Med 2005;32:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henckes A, Lion F, Cochard G et al. [Pulmonary oedema in scuba-diving: frequency and seriousness about a series of 19 cases]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2008;27:694–9. 10.1016/j.annfar.2008.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cordier PY, Coulange M, Polycarpe A et al. Immersion pulmonary oedema: a rare cause of life-threatening diving accident. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2011;30:699 10.1016/j.annfar.2011.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edmonds C, Lippmann J, Lockley S et al. Scuba divers’ pulmonary oedema: recurrences and fatalities. Diving Hyperb Med 2012;42:40–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lippmann J, Walker D, Lawrence CL et al. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2007. Diving Hyperb Med 2012;42:151–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smart DR, Sage M, Davis FM. Two fatal cases of immersion pulmonary oedema—using dive accident investigation to assist the forensic pathologist. Diving Hyperb Med 2014;44:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lippmann J, Lawrence C, Fock A et al. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2010. Diving Hyperb Med 2015;45:154–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fornes P, Lecomte D, Nicolas G. Sudden out-of-hospital coronary death in patients with no previous cardiac history. An analysis of 221 patients studied at autopsy. J Forensic Sci 1993;38:1084–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hart G. Exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy: a substrate for sudden death in athletes? Exp Physiol 2003;88:639–44. 10.1113/eph8802619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tavora F, Zhang Y, Zhang M et al. Cardiomegaly is a common arrhythmogenic substrate in adult sudden cardiac deaths, and is associated with obesity. Pathology 2012;44:187–91. 10.1097/PAT.0b013e3283513f54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dwyer N, Smart D, Reid DW. Scuba diving, swimming and pulmonary oedema. Intern Med J 2007;37:345–7. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01347.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ackerman MJ, Tester DJ, Porter CJ. Swimming, a gene-specific arrhythmogenic trigger for inherited long QT syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 1999;74:1088–94. 10.4065/74.11.1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Magder S, Linnarsson D, Gullstrand L. The effect of swimming on patients with ischemic heart disease. Circulation 1981;63:979–86. 10.1161/01.CIR.63.5.979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eckart RE, Scoville SL, Campbell CL et al. Sudden death in young adults: a 25-year review of autopsies in military recruits. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:829–34. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maron BJ, Epstein SE, Roberts WC. Causes of sudden death in competitive athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol 1986;7:204–14. 10.1016/S0735-1097(86)80283-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eckart RE, Shry EA, Burke AP et al. Sudden death in young adults: an autopsy-based series of a population undergoing active surveillance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1254–61. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ullal AJ, Abdelfattah RS, Ashley EA et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy as a cause of sudden cardiac death in the young: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 2016; 129:486–496.e2. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM et al. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol 1986;57:450–8. 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marijon E, Bougouin W, Périer MC et al. Incidence of sports-related sudden death in France by specific sports and sex. JAMA 2013;310:642–3. 10.1001/jama.2013.8711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Denoble PJ, Nelson CL, Ranapurwala SI et al. Prevalence of cardiomegaly and left ventricular hypertrophy in scuba diving and traffic accident victims. Undersea Hyperb Med 2014;41:127–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Desai AS, Jhund PS. After TOPCAT: what to do now in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Eur Heart J 2016. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjsem-2016-000146supp.pdf (87.5KB, pdf)