Abstract

Background

We set out to determine the predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors that influence cannabis use in young people aged 13 to 19 years in Shamva District, Zimbabwe.

Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional study focusing on the correlates of cannabis use was conducted among 311 school-going adolescents who were selected using multistage sampling.

Results

Eight percent of the students in our sample reported current use of cannabis. Associations were found between cannabis use and alcohol consumption (P < 0.001), cigarette smoking (P < 0.001), and having had engaged in sexual intercourse (P < 0.001). Significant relationships were found between recreational use of cannabis and having family members, friends, and parents who have used cannabis (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Students who reported using alcohol, smoking cigarettes, and having had engaged in sexual activity were more likely to use cannabis. There is need for identification of these risky behaviours among students, and ecological frameworks and holistic approaches in health promotion programming should be fostered in an effort to increase awareness of the potential harmful effects of cannabis use on adolescents' health and life outcomes.

Introduction

In 2013, cannabis was the most commonly used illicit drug worldwide, with a reported 180.6 million users aged 15 to 64 years.1 In Zimbabwe, the prevalence of cannabis use among adolescents has been estimated to be 9%.2 Cannabis use has been found to be higher in adolescence and young adulthood, and evidence suggests that adolescents who use cannabis have an increased risk of developing psychotic disorders in later years.3–5 Cannabis use disorders present a growing public health concern and can exacerbate existing mental health problems,5,6 as well as increase injuries, respiratory problems, and social problems, such as unemployment, low educational attainment, criminality,6 poor interpersonal relationships, and risky sexual behaviours.7

A number of factors have been found to predispose youth to cannabis use, chief among them being a history of tobacco smoking,8,9 alcohol use,10 being bullied,7 peer influence,11 and having dysfunctional families.12,13 On the other hand, some studies have found religion to be protective against the use of cannabis.14 In Shamva District, situated in northern Zimbabwe, adolescents constituted 64% of all patients presenting with substance-induced psychosis in the first quarter of 2013, and this proportion rose to 84% in the last quarter of the same year. This study aimed to determine the predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors that influence cannabis use in young people aged 13 to 19 years in Shamva District, Zimbabwe.

Methods

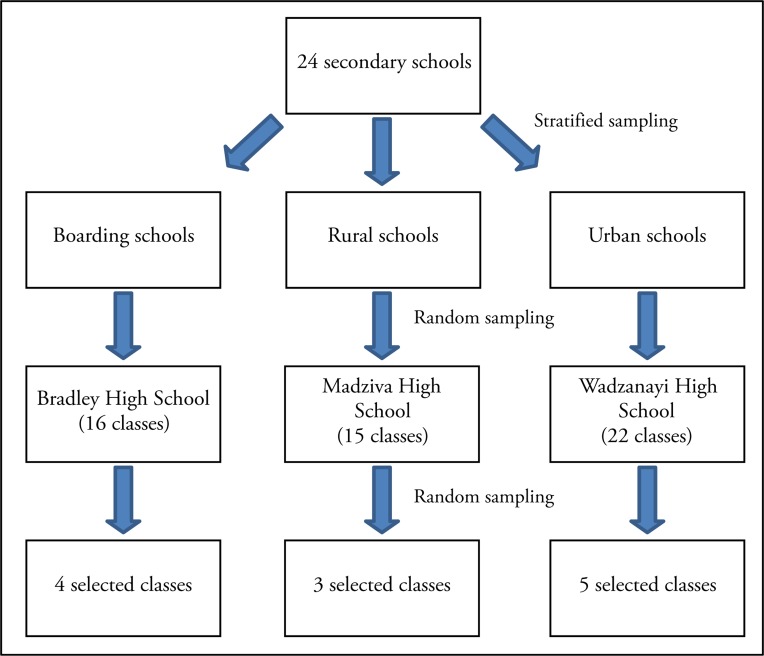

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Shamva District, Mashonaland Central Province, Zimbabwe, which is approximately 90 km northeast of Harare. The study sample was obtained using multistage sampling (Figure 1). A list was drawn up of all 24 high schools in Shamva District. The high schools were then stratified according to location and enrolment type (urban, rural, or boarding facility). Three schools were randomly selected from each stratum using the lottery method. The next stage involved picking classes from these schools, taking into consideration the overall size of the school. This resulted in a total of 12 classes, and all students (N = 350) in these classes were invited to participate in the study.

Figure 1.

Sampling design

Self-administered, Shona-language questionnaires were used to collect data on demographic factors, as well as predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling factors of cannabis use. Questionnaires were distributed to students in their classrooms. The questionnaire was based on constructs (predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors) borrowed from the PRECEDE-PROCEED Model.15 The following predisposing factors were considered: knowledge, attitudes, values, and beliefs related to cannabis use. The enabling factors that were considered included affordability, availability, and accessibility of cannabis, and the reinforcing factors were social support, education, and perceived consequences of cannabis use. We defined current use of cannabis as having used the substance within the 30 days immediately preceding data collection. In addition, we also defined lifetime prevalence as having ever used cannabis on one or more occasions in the past.

Ethics

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Joint Research Ethics Committee (JREC), University of Zimbabwe, and the Mashonaland Central Provincial Medical Directorate prior to data collection. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and, where appropriate, assent and parental consent were obtained before the students were enrolled into the study. Permission to gain entry into the schools was granted by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education.

Data analysis

Questionnaires were checked for completeness in the field, and data were entered into Epi Info version 3.5.3 statistical software. We summarised respondents' characteristics using descriptive statistics and conducted bivariate analyses to identify correlates of cannabis use among the participants. Data were analysed using the chi-square statistic and, where appropriate, the Fisher's exact statistic, with the significance level set at 5%.

Results

A total of 311 questionnaires were analysed out of the 350 distrubuted, giving a response rate of 88.9%. The remaining 39 questionnaires were discarded because of missing information. The mean age of students was 16.8 years and 42% of the respondents were female. Demographic characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Eight percent of our sample reported having used cannabis in the previous 30 days and 15.6% reported ever using cannabis. Students who used cannabis every day constituted 5.4% of the sample; 1.3% used cannabis weekly and 3.5% used cannabis monthly. The participants who reported current cannabis use were all males. The mean age of initiation of cannabis use was 15.4 years.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants

| Demographic variable | Frequency | % | |

| Age | 15 years and below | 61 | 19.6 |

| 16 years and above | 250 | 80.4 | |

| Sex | Male | 180 | 58.0 |

| Female | 131 | 42.0 | |

|

Year level in school |

3 | 81 | 26.0 |

| 4 | 83 | 26.7 | |

| 5 | 50 | 16.1 | |

| 6 | 97 | 31.2 | |

| Religion | Apostolic | 89 | 28.7 |

| Catholic | 56 | 18.0 | |

| Muslim | 7 | 2.3 | |

| Pentecostal | 81 | 26.0 | |

| Protestant | 53 | 17.0 | |

| Traditional | 25 | 8.0 | |

Predisposing and enabling factors

Eighty-four percent of respondents reported receiving information about the dangers of cannabis use. Out of these participants, 11.8% had received this information at church, 5.1% had received it at a health facility, 20.1% had received this information at home, and 72% had received such information at school. Awareness of possible mental health problems associated with using cannabis was reported by 135 participants (43.4%), while 234 participants (75%) reported knowledge of diseases caused by cannabis use.

Including those who were already using the substance at the time of data collection, 42 participants (13.4%) reported that they would likely use cannabis if it were legalised; most of the participants who reported this finding were male (85.7%). Indeed, males were generally more likely to report cannabis use (or intention to use cannabis in the future) than females (P < 0.001).

Alcohol users were more likely to use cannabis (P < 0.001). Similarly, 80% of those who reported cigarette smoking also used cannabis. There was a significant association (P < 0.001) between smoking cigarettes in the previous 30 days and intention to use cannabis upon hypothetical future legalisation.

Significant associations were also found between cannabis use and a history of sexual activity, as well as having friends, parents, and other family members who also used cannabis (Table 2). There was no association between use of cannabis and having a history of being bullied (P = 0.59).

Table 2.

Associations between cannabis use and questionnaire items

| Do you use cannabis? |

||||

| Variable | Yes | No | Total | P value |

| Gender | ||||

| (n = 311) | ||||

| Male | 25 | 155 | 180 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 0 | 131 | 131 | |

| Drink alcohol | ||||

| (n = 311) | ||||

| Yes | 14 | 10 | 24 | < 0.001 |

| No | 11 | 276 | 287 | |

| Smoke cigarettes | ||||

| (n = 310) | ||||

| Yes | 16 | 4 | 20 | < 0.001 |

| No | 9 | 285 | 294 | |

| Have been bullied | ||||

| (n = 311) | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 48 | 52 | 0.59 |

| No | 21 | 238 | 259 | |

| Engaged in sexual activity | ||||

| (n = 311) | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 31 | 39 | 0.004 |

| No | 17 | 255 | 272 | |

| Friends who use cannabis | ||||

| (n = 311) | ||||

| Yes | 24 | 17 | 41 | < 0.001 |

| No | 1 | 269 | 270 | |

| Parents who use cannabis | ||||

| (n=311) | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 4 | 8 | 0.0018 |

| No | 21 | 285 | 306 | |

| Family members who use cannabis | ||||

| (n=311) | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 79 | 97 | < 0.001 |

| No | 7 | 207 | 214 | |

The main sources of cannabis among students were friends (76%) and family members (12%). About one-fifth (18.5%) of the students reported purchasing cannabis from the street for about US$1.00 per marijuana cigarette.

Reinforcing factors

The most cited reasons for using cannabis were boosting self-confidence (60%), having a good time (12%), fitting in with peers (16%), and coping with stress (12%). Out of the students who had previously used cannabis but then stopped, 4 attributed their cessation to not enjoying the smoke from cannabis, 1 reported that using cannabis made him sick, and 9 reported cessation of cannabis use because of a realisation or understanding of the potential harmful effects of the drug.

Students who did not use cannabis stated the following reasons for their abstinence: it is illegal (20.4%); no known sources for purchasing (2.5%); following parental orders (14.6%); religious beliefs (25.8%); aversion to smoke (21.7%); and negative health effects (62.7%).

Discussion

Although many young people use cannabis without experiencing adverse effects, cannabis is potentially harmful,16 especially with initiation at younger ages, or in association with pre-existing psychological vulnerabilities. This report discusses only recreational cannabis consumption and, from a public health perspective and for the purposes of this study and write-up, we viewed cannabis use (and misuse) by young people as mostly harmful. The results of this study will ideally guide future studies that further examine detrimental and beneficial effects of cannabis use by adolescents in Zimbabwe and the surrounding region, in order to propose favourable interventions and policies related to marijuana consumption in the area.

Although this study was conducted primarily in a periurban area in Zimbabwe, the results are likely representative of most regions within the country. The prevalence of cannabis use among high school students in the study was 8%, which is congruent with results from studies conducted in urban Harare.2,9 However, the lifetime prevalence of cannabis use in the Shamva sample was 15.6%, implying that some adolescents in Shamva District experiment with cannabis but do not become habitual cannabis users.

All the students who reported current cannabis use were male. Girls may be less likely than boys to experiment with intoxicating substances because of differing societal and cultural expectations between the sexes in Zimbabwe. With that in mind, underreporting may at least partly explain the absence of female students who reported cannabis use. Future research specifically investigating the association between gender and cannabis use in Zimbabwe would augment these findings.

Most students in our sample reported acquiring information on the dangers of cannabis use at school, implying that school health programmes may be effective in disseminating health information. Indeed, school enrolment has been found to be a protective factor against illicit drug use.7 A smaller proportion of students reported learning about the effects of cannabis at health facilities, which suggests a role for health systems and health education interventions in informing young Zimbabweans about the effects of cannabis use.

The strong association that was found between alcohol consumption and cannabis use is in line with findings elsewhere, including a study by Behrendt et al.,10 in which 99% of cannabis users also reported alcohol use. The implication here is that interventions that aim to reduce underage alcohol consumption may, by association, also reduce initiation of cannabis use, and vice versa. Similarly, the strong relationship between smoking tobacco and using cannabis is well established,9,10 and preventing experimentation or habitual use of one of these substances would likely mean largely preventing use of the other, and this would have important public health implications when it comes to preventing respiratory, cardiovascular, and mental illnesses.

Our study found no association between being bullied and using cannabis, which contradicts the findings from a study of Zambian adolescents who were three times more likely to use cannabis if they had previously been bullied.7 That study of in-school adolescents in Zambia also found a strong relationship between having engaged in sexual activity and using cannabis,7 which was consistent with our findings.

Our results showed that students who used cannabis often sourced the drug from friends and family members. The strong relationship between cannabis use and having parents, friends, and family members who also use the drug calls for ecological frameworks and holistic approaches in health promotion programming, rather than targeting the adolescents only.

Conclusions

Study participants who reported alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and engaging in sexual activity were more likely to use cannabis than those who did not. Additionally, those with friends, parents, and other family members who used cannabis were more likely to use the substance. Both individual and environmental factors were important determinants of cannabis use. Ecological frameworks and holistic approaches should therefore be used in designing adolescent health promotion interventions to curb harmful use of cannabis among adolescents. Additionally, schools can provide an ideal setting where these interventions can be instituted and strengthened.

References

- 1.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), author World drug report 2013 [Internet] New York: United Nations; 2013. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/secured/wdr/wdr2013/World_Drug_Report_2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudatsikira E, Maposa D, Mukandavire Z, Muula A, Siziya S. Prevalence and predictors of illicit drug use among school-going adolescents in Harare, Zimbabwe. Ann Afr Med. 2009;8(4):215. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.59574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGrath J, Welham J, Scott J, Varghese D, Degenhardt L, Hayatbakhsh MR, et al. Association between cannabis use and psychosis-related outcomes using sibling pair analysis in a cohort of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 May 1;67(5):440. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manrique-Garcia E, Zammit S, Dalman C, Hemmingsson T, Andreasson S, Allebeck P. Characteristics of schizophrenia in persons with and without a history of cannabis use. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(Suppl 1):55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubino T, Parolaro D. Cannabis abuse in adolescence and the risk of psychosis: A brief review of the preclinical evidence. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2014;52:41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copeland J, Clement N, Swift W. Cannabis use, harms and the management of cannabis use disorder. Neuropsychiatry. 2014;4(1):55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siziya S, Muula AS, Besa C, Babaniyi O, Songolo P, Kankiza N, et al. Cannabis use and its socio-demographic correlates among in-school adolescents in Zambia. Ital J Pediatr. 2013;39(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-39-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korhonen T, van Leeuwen AP, Reijneveld SA, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Huizink AC. Externalizing behavior problems and cigarette smoking as predictors of cannabis use: the TRAILS study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(1):61–69. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201001000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandason T, Rusakaniko S, Thun M, Silva VL da C e, Chapman S, Ball K, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of smoking among secondary school students in Harare Zimbabwe. Tob Induc Dis. 2010;8(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behrendt S, Beesdo-Baum K, Höfler M, Perkonigg A, Bühringer G, Lieb R, et al. The relevance of age at first alcohol and nicotine use for initiation of cannabis use and progression to cannabis use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123(1):48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tucker JS, de la Haye K, Kennedy DP, Green HD, Pollard MS, Ali MM, et al. Peer influence on marijuana use in different types of friendships. J Adolesc Heal. 2014 Jan;54(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coggans N. Risk factors for cannabis use [Internet] In: Sznitman SR, Olsson B, Room R, editors. A cannabis reader: global issues and local experiences — perspectives on cannabis controversies, treatment and regulation in Europe: volume 2. Lisbon: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction; 2008. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/1928/Cannabisvolume2FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), author Preventing drug use among children and adolescents: a research-based guide for parents, educators, and community leaders [Internet] 2nd ed. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/preventingdruguse_2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gmel G, Mohler-Kuo M, Dermota P, Gaume J, Bertholet N, Daeppen J-B, et al. Religion is good, belief is better: religion, religiosity, and substance use among young swiss men. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48(12):1085–1098. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.799017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green L, Kreuter M. Health program planning: an educational and ecological approach. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2005. 610 p. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arseneault L, Cannon M, Poulton R, Murray R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, et al. Cannabis use in adolescence and risk for adult psychosis: longitudinal prospective study. BMJ. 2002 Nov 23;325(7374):1212–1213. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]