Abstract

Background:

Yoga has become more popular among people in the United States and has been touted by both yoga participants as well as some physicians and researchers for its health benefits. While the health benefits have been studied, the frequency of injury among yoga participants has not been well documented.

Purpose:

Injury incidence, rates, and types associated with yoga in the United States have not been quantified. This study estimates US yoga-associated injury incidence and characterizes injury type over a 13-year period.

Study Design:

Descriptive epidemiology study.

Methods:

Data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) from 2001 to 2014 were used to estimate the incidence and type of yoga-associated injuries. The number and age distribution of yoga participants was estimated using data from National Health Statistics Reports. These national population estimates were applied to the NEISS data to determine injury rates overall and stratified according to age categories.

Results:

There were 29,590 yoga-related injuries seen in hospital emergency departments from 2001 to 2014. The trunk (46.6%) was the most frequent region injured, and sprain/strain (45.0%) accounted for the majority of diagnoses. The injury rate increased overall from 2001 to 2014, and it was greatest for those aged 65 years and older (57.9/100,000) compared with those aged 18 to 44 years (11.9/100,000) and 45 to 64 years (17.7/100,000) in 2014.

Conclusion:

Participants aged 65 years and older have a greater rate of injury from practicing yoga when compared with other age groups. Most injuries sustained were to the trunk and involved a sprain/strain. While there are many health benefits to practicing yoga, participants and those wishing to become participants should confer with a physician prior to engaging in physical activity and practice only under the guidance of certified instructors.

Keywords: yoga, injury, alternative medicine, elderly

The practice of yoga has become increasingly commonplace in American society, with the number of participants nearly doubling from 5.1% to 9.5% of adults in the United States from 2007 to 2012.11 Yoga is an encompassing activity and can refer to an array of physical and mental activities, including stretching, physical postures, breath control, and meditation.12 Yoga is touted for its overall health benefits and mental well-being; participants indicate indirect health benefits through improved physical fitness and reduced stress as well as direct health benefits such as reduced back and neck pain, arthritis, and anxiety.25

Recently, there have been a number of studies that sought to compare outcome measures and burdens of various diseases while incorporating yoga as complementary therapy. For example, a review article of 13 nonrandomized and 12 randomized controlled trials of patients with type 2 diabetes found that the practice of yoga promoted significant improvements in glycemic control, lipid levels, and body composition.22 Yoga has been shown to improve depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance among pregnant women as well as improving fatigue and depression among breast cancer patients.4,7,15,18,19,26,41 Yoga has improved arrhythmia burden, heart rate, and blood pressure among patients with atrial fibrillation.13,23 Additionally, yoga has been shown to improve outcomes for stroke patients as well as those with chronic neck and back pain.24,31 For older individuals, a lack of balance and falling can indicate a physical decline; however, yoga has been shown to improve balance and self-perception of falling.6,27,30,33

According to the National Institutes of Health, yoga is safe for healthy individuals when practiced with a well-educated instructor; however, caution is given that adverse effects can occur, including nerve damage and even stroke.25 In an Australian national survey, 78.7% of respondents reported never having been injured while practicing yoga, and among those who did report injuries, many were strains or related to injuries that occurred more than 12 months prior.28 A survey of more than 1300 yoga teachers worldwide indicated that the most frequent injuries occurred to the neck, lower back, knee, shoulder, and wrist, and the most common causes were poor technique, poor instruction, previous injury, and excess effort.16 Another study found that less than 1% of yoga participants who were injured stopped participating due to injury.20 When examining the risks and benefits of yoga as an alternative therapy for osteoporosis and spinal movement in aging adults, it was found that moderate flexion and extension was beneficial; however, caution is given that therapy should be individualized, as bone density can differ and some yoga positions can be damaging.32,33

A case series of yoga-related injuries from 1991 to 2010 at a single hospital emergency department in Canada found that 73% of cases were seen after 2005, showing that the number of injuries is increasing.29 They found that sprain (34%) was the most common injury, and the lower extremity (42%) was the most frequently injured body region.29 Additionally, children were significantly more likely to be injured than adults; however, more adults needed treatment for injuries.29

While the practice of yoga is beneficial for many regardless of health status, the possibility of injury due to the practice still exists. Additionally, the incidence of yoga injuries in the United States is not well characterized. The purpose of this study was to determine the number of yoga-related injuries in the United States from 2001 to 2014 seen by emergency departments and describe injury characteristics so the risk of injury involved in participating in yoga is established.

Methods

Data Source

The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) database from 2001 to 2014 was used to identify yoga-related injuries.37 NEISS is a database maintained by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), utilizing a national probability sample of 100 hospitals in the United States.38 Information is collected by NEISS-trained coordinators at participating facilities to acquire information on emergency department visits involving various consumer products, including sporting activities. Narratives entered into the database are reviewed by CPSC staff to ensure proper categorization and case validity.38,39 Institutional review board exemption was obtained from the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

While NEISS codes for various sporting activities, yoga is not a specific category; therefore, to determine whether cases were related to yoga, narratives were searched for the term yoga. Narratives were then reviewed to exclude observations that did not clearly involve the practicing of yoga. For example, case narratives similar to “neck pain unsure if from lifting or yoga” or “fell off toilet after sauna/steam/yoga” were excluded. Additionally, observations involving yoga-related equipment but not the actual practice of yoga were excluded, (eg, “[patient] tripped over wife’s yoga ball and fell hitting head on floor”). To ensure correct classification of yoga-related observations, narratives were reviewed by a second person and discrepancies were discussed until concordance was achieved. Patients younger than 18 years were excluded from this study due to lack of information on the number of youth yoga participants in the United States. In all, 818 observations were reviewed that contained the term yoga. After review, 774 were deemed related to the practice of yoga and were used to determine the weighted estimates of the total number of yoga injuries from 2001 to 2014.

Variable Definitions

Information on the patient’s age, sex, race, incident locale, body part affected, diagnosis, and disposition were collected by the NEISS. Three age categories were created: 18 to 44 years, 45 to 64 years, and older than 65 years. Race was classified as white, black, other, and not recorded. Observations listed as white, black, and not recorded were categorized as such, and “other” included other, Asian, American Indian/Alaska native, and native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Incident locale was categorized as place of recreation, home, not recorded, and other. “Place of recreation” corresponded to place of recreation or sports and “home” included locales designated as home and mobile/manufactured home. The category “other” encompassed farm/ranch, street or highway, other public property, industrial, and school. “Not recorded” included all cases were the location was not recorded.

The body region injured was classified into trunk, upper limb, lower limb, head, and other. “Trunk” included shoulder, upper trunk, lower trunk, and pubic region. Injuries to “upper limb” included the elbow, lower arm, wrist, upper arm, hand, and finger; “lower limb” encompassed the knee, lower leg, ankle, upper leg, foot, and toe. Injuries to the “head” were composed of injuries sustained to the head, face, eyeball, mouth (including lips, teeth, and tongue), ear, and neck. “Other” included all other parts of body (more than 50%), not recorded, and internal. Injury diagnoses were categorized as abrasion, dislocation, fracture, strain/sprain, not stated, and other. Each diagnosis corresponded to the NEISS diagnosis with the exception of “other,” which included concussion, foreign body, hematoma, laceration, nerve damage, internal organ injury, puncture, hemorrhage, poisoning, and dermatitis/conjunctivitis. Hospital disposition included treated and released, admitted, and other. “Other” comprised those treated and transferred to another hospital, held for observation, left without being seen or against medical advice, and not recorded.

Statistical Analysis

In this descriptive epidemiology study, frequencies for patient demographic and diagnosis variables were calculated using weighted estimates with 95% confidence limits (95% CI) to account for sampling used by the NEISS. Incidence rates were calculated based on the estimated number of yoga participants in the US. To determine the number of yoga participants, the proportion of the US population who practiced yoga was acquired from the 2002, 2007, and 2012 National Health Statistics Reports.2,11 These proportions were then applied to US census population estimates, by age group, for each corresponding year to establish the estimated number of participants.35,36 For the remaining years, the 2015 Sports Fitness Industry Association report was used to estimate the number of participants in each age group for 2001 to 2006, 2008 to 2011, and 2013 to 2014.34

To determine the ratio of male to female participants, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) (2011-2013) was used.8,9 According to the BRFSS, males represented 16.9% and females 83.1% of yoga participants during this period. These proportions were applied to the total estimated number of participants to quantify the number of male and female participants per year. Due to the lack of available information, the ratio of male and female participants was assumed to be constant from year to year.

Results

From 2001 to 2014 there were an estimated 29,590 yoga-related injury cases that sought treatment at US emergency departments. As shown in Table 1, the majority (53.2%) were aged 18 to 44 years and female (81.4%). A place of recreation (45.5%) was the most frequent locale at the time of injury. Injuries to the trunk (46.6%) and lower limb (21.9%) accounted for the majority of body regions injured, and strain/sprain was the most common diagnosis (45.03%).

TABLE 1.

Frequency of Demographic and Injury Characteristics of Yoga-Related Injuries, 2001 to 2014 (N = 774)

| Variable | n (95% CI) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Weighted estimate | 29,590 (19,992-39,188) | |

| Age category, y | ||

| 18-44 | 15,729 (10,788-20,670) | 53.16 |

| 45-64 | 9948 (6409-13488) | 33.62 |

| 65+ | 3912 (1722-6103) | 13.22 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 5519 (2919-8120) | 18.65 |

| Female | 24,071 (16,915-31,226) | 81.35 |

| Race | ||

| Black | 1752 (939-2565) | 5.92 |

| White | 17,431 (10,845-24,017) | 58.91 |

| Other | 1711 (278-3145) | 5.78 |

| Not recorded | 8696 (4369-13,022) | 29.39 |

| Incident locale | ||

| Place of recreation | 13,465 (6863-20,068) | 45.51 |

| Home | 4357 (2895-5819) | 14.73 |

| Other | 2369 (1353-3384) | 8.01 |

| Not recorded | 9399 (7014-11,784) | 31.76 |

| Body region injured | ||

| Trunk | 13,791 (9284-18,298) | 46.61 |

| Lower limb | 6492 (4291-8693) | 21.94 |

| Head | 5009 (2583-7434) | 16.93 |

| Upper limb | 2607 (1659-3556) | 8.81 |

| Other | 1691 (667-2714) | 5.71 |

| Injury diagnosis | ||

| Strain/sprain | 13,324 (9163-17,484) | 45.03 |

| Not stated | 9678 (6358-12,998) | 32.71 |

| Other | 3028 (1647-4408) | 10.23 |

| Fracture | 1408 (362-2454) | 4.76 |

| Abrasion | 1180 (546-1815) | 3.99 |

| Dislocation | 972 (127-1817) | 3.28 |

| Hospital disposition | ||

| Treated and released | 27,984 (19,112-36,857) | 94.57 |

| Admitted | 1006 (443-1570) | 3.4 |

| Other | 599 (171-1027) | 2.03 |

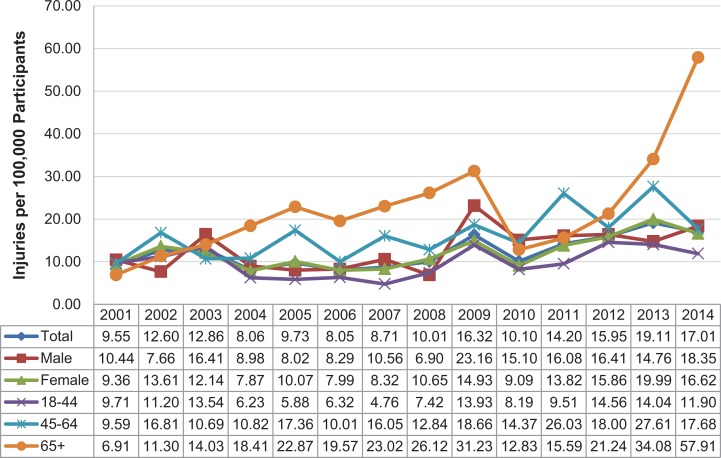

The overall injury rate increased from 9.55 per 100,000 participants in 2001 to 17.01 per 100,000 participants in 2014 (Figure 1). In general, injury rates fluctuated consistently when comparing males and females. Those aged 18 to 44 years had an injury rate of only 6.23 per 100,000 participants in 2004 and 11.90 per 100,000 in 2014. Compared with the overall injury rates from 2004 to 2011, the rate among those aged 18 to 44 years was considerably lower. In contrast, those aged ≥65 years had far greater injury rates from 2004 to 2014 when compared with the overall rates; specifically, in 2004, those ≥65 years had 18.41 injuries per 100,000 participants compared with 57.91 injuries per 100,000 in 2014.

Figure 1.

Yoga-related injury rate (per 100,000 participants) by sex and age group, 2001 to 2014.

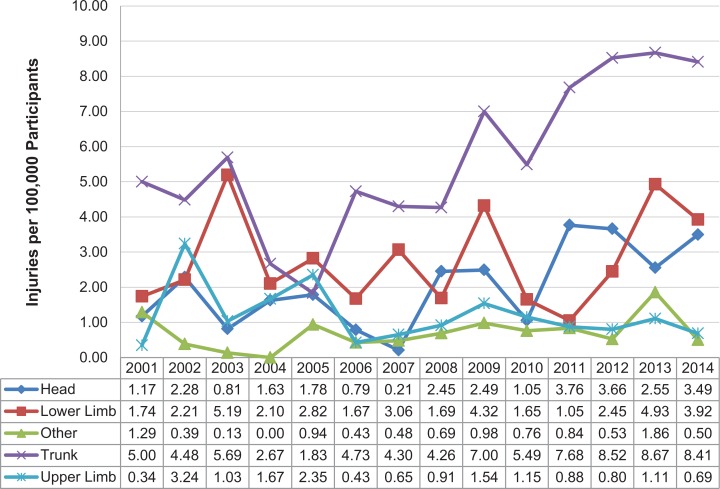

Examining injury rates stratified by body region injured (Figure 2), rates for injuries to the trunk increased from 2001 to 2014. Additionally, trunk injury rates were considerably greater than other regions, with 8.41 injuries per 100,000 participants in 2014. Overall, injury rates for the head and lower limb increased from 2001 to 2014. Rates between head and lower limb injuries were comparable with 3.49 injuries per 100,000 participants for head and 3.92 injuries per 100,000 participants for lower limb in 2014.

Figure 2.

Yoga-related injury rate (per 100,000 participants) by body region injured, 2001 to 2014.

When examining injury rates for the overall period from 2001 to 2014 by body region injured stratified by sex and age category (Table 2), those 65 years and older had the greatest rates for each body region. For injury diagnosis, those aged 45 to 64 years had a rate of 8.1 per 100,000 for strain/sprain, and those aged 65+ years had a rate of 7.20 per 100,000. The rate of fractures among those 65 years and older was nearly 3 times that of those aged 45 to 64 years (2.21 per 100,000 vs 0.75 per 100,000). When comparing hospital disposition, the rate of hospital admission was greatest for those 65 years and older at 2.09 per 100,000.

TABLE 2.

Injury Rate (Injuries per 100,000 Participants) by Body Region Injured, Injury Diagnosis, and Hospital Disposition Stratified by Sex and Age Category for Yoga-Related Injuries, 2001 to 2014

| Injury Rate by Sex | Injury Rate by Age Category, y | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | 18-44 | 45-64 | 65+ | |

| Body region injured | |||||

| Trunk | 6.90 | 5.85 | 4.54 | 8.67 | 11.18 |

| Lower limb | 2.62 | 2.89 | 2.18 | 3.91 | 5.49 |

| Head | 2.32 | 2.16 | 2.21 | 1.83 | 3.41 |

| Upper limb | 0.61 | 1.25 | 0.87 | 1.49 | 2.53 |

| Other | 1.33 | 0.61 | 0.32 | 1.25 | 3.07 |

| Injury diagnosis | |||||

| Strain/sprain | 5.10 | 5.98 | 4.84 | 8.10 | 7.20 |

| Not stated | 5.51 | 3.96 | 2.89 | 6.16 | 10.58 |

| Other | 2.05 | 1.17 | 1.01 | 1.70 | 3.07 |

| Fracture | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.41 | 0.75 | 2.21 |

| Abrasion | 0.29 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 1.55 |

| Dislocation | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 1.07 |

| Hospital disposition | |||||

| Treated and released | 12.66 | 12.15 | 9.74 | 16.00 | 23.40 |

| Admitted | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.79 | 2.09 |

| Other | 0.75 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.20 |

Discussion

The incidence of yoga-related injuries increased from 2001 to 2014. Of note, the analysis indicates that injury rates increased 8-fold for those aged 65 years or older; the injury rate among those 18 to 44 years only increased fractionally and doubled among those 45 to 64 years during this period. In accordance with the finding that sprain/strain was the most common injury, a study of 66 cases at a Canadian emergency department found that sprain was the frequent injury (34%).29 Additionally, when looking from 1991 to 2010, they found that 73% of cases occurred after 2005, which supports the finding that yoga injury rates are increasing.29

While lack of technique and experience could explain some of the increase in injury incidence, the finding of greater incidence among those older than 65 years is highlighted by the fact they only had a 2% increase in participants while those 18 to 44 years had a 5% increase. If lack of technique and experience alone was the cause for adverse yoga events, the analysis would show that those aged 18 to 44 years had the greatest increase in injury rates. The results suggest that regardless of technique and experience, people older than 44 years, and especially those older than 65 years, are at greater risk of injury associated with practicing yoga.

The high rate of injury among those 65 years or older could be explained by biological changes induced through aging. For example, in a study that compared young (mean, 28.9 years) and old (mean, 60.2 years) runners, older individuals had significantly lower flexibility and strength in the hip and ankle.17 With increased age, bone density decreases, causing bones to break more easily, joint/spinal issues, and cartilage decreases in lower body joints.3,21,32 This notion is supported by the fact that those aged 65 years and older had a fracture rate of 2.21 per 100,000 compared with a rate of 0.41 per 100,000 among those 18 to 44 years and 0.75 per 100,000 among those 45 to 64 years. Additionally, decreased muscle density, sarcopenia, and changes in muscle fiber type reduce muscle strength and flexibility.14,21,40 The relevance of physical decline, both reduced muscle mass and bone density, as playing a role in injuries among older individuals is highlighted by the fact that in 2014, an unintentional fall was the lead cause of injury death among those 65 years and older.10

Since there was an increase in incidence of injury among all age groups from 2001 to 2014, factors besides aging must also be present. One potential cause for the increase is lack of qualified instructors.16 With an increase in the number of yoga participants, there has been increased need for instructors; according to a 2015 article, there are more registered yoga instructors than ever before, even more than needed by the industry.1 With the increase in both the number of certified instructors and injuries it would seem that there is a potential lack of appropriate education even for certified instructors. Some in the industry agree with this assessment and state that training programs, particularly dominated by 1 alliance standard, do not prepare instructors well to prevent injury.1,5 They also propose that instead of larger group certification courses, the standard should be more traditional yoga instruction with 1-on-1 training.1,5

With the many positive health benefits associated with practicing yoga, the injury analysis provided in this article should not deter individuals, even older individuals, from participating. However, caution should be used, as with any physically exertive activity; those wanting to participate should discuss their physical health with their physician.25 Although one should participate in yoga at a well-known studio with qualified instructors, more important, an individual should not engage in poses that they feel are beyond their physical limitations.25

This study is limited in that the cases were estimates of individuals who sought treatment only at emergency departments. Moreover, only narratives that included the term yoga were used since yoga is not a specifically tracked sport. Due to this, estimates are likely lower than the total number of yoga-related injuries occurring in the United States since treatment could have been sought elsewhere or cases could have been classified as “sport or recreational activity not listed elsewhere” without mention of the specific activity in the narrative. Additionally, since older individuals are more likely to have severe injuries associated with yoga and therefore need emergency help, their rate of injury when compared with younger age groups is likely elevated. The population used to determine injury rates was also compiled using data from several sources, which could lead to error in estimating injury rates. Future research of yoga-related injuries would benefit from a well-defined participant population to include those younger than 18 years. Future research would also improve if information was obtained from other sources so that incidence rates comparing private practice to emergency departments could be compared.

Conclusion

Yoga is a safe form of exercise with positive impacts on various aspects of a person’s health; however, those wishing to practice yoga should be cautious and recognize personal limitations, particularly individuals 65 years and older. National standards for yoga instructor certification should be created and should more aggressively teach information about safety and injury prevention.

Footnotes

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution.

References

- 1. Bachman R. Everyone is a yoga teacher today—to keep people coming back, studios offer certification classes; the number of new teachers is growing faster than new students. Wall Street Journal. September 2, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2008;12:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benjamin C. What causes bone loss? Medline Plus Medical Encyclopedia. Bethesda, MD: US National Library of Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Birdee GS, Legedza AT, Saper RB, Bertisch SM, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Characteristics of yoga users: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1653–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown J. Yoga alliance is ruining yoga. https://americanyoga.school/yoga-alliance-ruining-yoga/. Accessed March 21, 2016.

- 6. Carpenter CR, Scheatzle MD, D’Antonio JA, Ricci PT, Coben JH. Identification of fall risk factors in older adult emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carson JW, Carson KM, Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Shaw H, Miller JM. Yoga for women with metastatic breast cancer: results from a pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;33:331–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2011.htm. Updated 2013. Accessed December 1, 2015.

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2014.html. Updated 2014. Accessed December 1, 2015.

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: Data and statistics (WISQARS). http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal.html. Published 2014. Accessed March 21, 2016.

- 11. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;79:1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cramer H, Langhorst J, Dobos G, Lauche R. Associated factors and consequences of risk of bias in randomized controlled trials of yoga: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deutsch SB, Krivitsky EL. The impact of yoga on atrial fibrillation: a review of The Yoga My Heart Study. J Arrhythm. 2015;31:337–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Evans WJ, Campbell WW. Sarcopenia and age-related changes in body composition and functional capacity. J Nutr. 1993;123 (2 suppl):465–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Field T, Diego M, Delgado J, Medina L. Tai chi/yoga reduces prenatal depression, anxiety and sleep disturbances. Comp Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19:6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fishman LM, Saltonstall E, Genis S. Yoga therapy in practice; understanding and preventing yoga injuries. Int J Yoga Ther. 2009;19:123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fukuchi RK, Stefanyshyn DJ, Stirling L, Duarte M, Ferber R. Flexibility, muscle strength and running biomechanical adaptations in older runners. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2014;29:304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gong H, Ni C, Shen X, Wu T, Jiang C. Yoga for prenatal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gura ST. Yoga for stress reduction and injury prevention at work. Work. 2002;19:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holton MK, Barry AE. Do side-effects/injuries from yoga practice result in discontinued use? Results of a national survey. Int J Yoga. 2014;7:152–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hurd R. Aging changes in the bones—muscles—joints In: Medline Plus Medical Encyclopedia. Bethesda, MD: US National Library of Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Innes KE, Selfe TK. Yoga for adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of controlled trials. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:6979370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lakkireddy D, Atkins D, Pillarisetti J, et al. Effect of yoga on arrhythmia burden, anxiety, depression, and quality of life in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: the YOGA My Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1177–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Michalsen A, Traitteur H, Lüdtke R, et al. Yoga for chronic neck pain: a pilot randomized controlled clinical trial. J Pain. 2012;13:1122–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine; National Institutes of Health. Yoga for health. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/yoga/introduction.htm. Updated 2013. Accessed March 1, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26. Newham JJ, Wittkowski A, Hurley J, Aplin JD, Westwood M. Effects of antenatal yoga on maternal anxiety and depression: a randomized controlled trial. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31:631–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nick N, Petramfar P, Ghodsbin F, Keshavarzi S, Jahanbin I. The effect of yoga on balance and fear of falling in older adults. PM R. 2016;8:145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Penman S, Cohen M, Stevens P, Jackson S. Yoga in Australia: results of a national survey. Int J Yoga. 2012;5:92–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Russell K, Gushue S, Richmond S, McFaull S. Epidemiology of yoga-related injuries in Canada from 1991 to 2010: a case series study. Int J Injury Control Safety Promot. 2016;23:284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Russell MA, Hill KD, Blackberry I, Day LL, Dharmage SC. Falls risk and functional decline in older fallers discharged directly from emergency departments. J Gerontol. 2006;61:1090–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schmid AA, Miller KK, Van Puymbroeck M, DeBaun-Sprague E. Yoga leads to multiple physical improvements after stroke, a pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22:994–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sinaki M. Yoga spinal flexion positions and vertebral compression fracture in osteopenia or osteoporosis of spine: case series. Pain Pract. 2013;13:68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smith EN, Boser A. Yoga, vertebral fractures, and osteoporosis: research and recommendations. Int J Yoga Ther. 2013;23:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sports and Fitness Industry Association. Yoga. Silver Spring, MD: Sports and Fitness Industry Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35. US Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population by sex, single year of age, race alone or in combination and Hispanic origin for the US: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014 American Fact Finder. http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. Accessed December 10, 2015.

- 36. US Census Bureau. Intercensal estimates of the resident population by single year of age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin for the US: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2010. https://www.census.gov/popest/data/intercensal/national/nat2010.html. Accessed December 10, 2015.

- 37. US Consumer Product Safety Commission. NEISS Coding Manual. Bethesda, MD: US Consumer Product Safety Commission; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38. US Consumer Product Safety Commission. The NEISS sample (design and implementation), 1997-present. https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_2001d011-6b6.pdf. Published 2001. Accessed March 21, 2016.

- 39. US Consumer Product Safety Commission; Division of Hazard and Injury Data Systems. The national electronic injury surveillance system; a tool for researchers. https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_2000d015.pdf. Published 2000. Accessed March 21, 2016.

- 40. Villa-Forte A. Effects of aging on the musculoskeletal system Merck Manuals. Kenilworth, NJ: Merck & Co; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yagli NV, Ulger O. The effects of yoga on the quality of life and depression in elderly breast cancer patients. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2015;21:7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]