Highlights

-

•

Roux-en Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) is the most commonly utilized bariatric procedure.

-

•

RYGB excludes a portion of the stomach to further endoscopic examination.

-

•

A case of poorly differentiated antral gastric carcinoma after RYGB is described.

-

•

Diagnosis was delayed due to scarce symptomatology and confounding factors.

-

•

A strict follow-up in post-RYGB patients was highly suggested for an early diagnosis of malignant gastric cancer.

Keywords: Chylous ascites, Gastric bypass, Gastric cancer, Morbid obesity

Abstract

Introduction

We described the case of a highly aggressive antral gastric carcinoma with a scarce symptomatology, in a patient undergone Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) for obesity.

Presentation of case

A 61 year-old white man in apparent good health, who underwent laparoscopic RYGB for obesity 18 months earlier, with a loss of 30 kg, reported a sudden abdominal distension and breath shortness with a weight gain of 5 kg in few days. Endoscopy of both upper gastro-intestinal tract and the colon were performed along with CT-scan and positron-emission tomography (PET) CT- scan. A biopsy of the palpable lymph node in the left supraclavicular fossa was taken for analysis. Abdominal paracentesis produced milky fluid, while citrine pleural fluid was aspirated by thoracentesis. Immunochemistry studies of the lymph node biopsy revealed tumor cells positive for cytokeratin (CK)7 and CK20, CDX2 and CAM 5.2 and negative for HER2 and TTF1 suggesting colon cancer. The colon and upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy were normal. A CT-scan and positron-emission tomography (PET) with 2-[fluorine-18]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG) showed an intense FDG-uptake in the gastric antrum and in the lymph nodal chains. Given these findings, a diagnosis of poorly differentiated antral gastric carcinoma with multiple lymph node metastases was raised.The patients died 4 months after diagnosis.

Discussion

RYGB is a widely performed bariatric operation and no data are reported on the risk of developing gastric cancer in the excluded stomach.

Conclusion

This case report suggests that great attention should be devoted to post-RYGB patients for an early diagnosis of malignant gastric cancer.

1. Introduction

According to the epidemic increases in prevalence of obesity in the last decades, the use of bariatric surgery is constantly on the rise, not only to cure obesity itself but also to prevent obesity-related diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases [1], [2]. So far, one of the most commonly utilized surgical procedure, even in adolescents, is Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) that can be performed laparoscopically, and it is considered the “gold standard” treatment for morbid obesity. RYGB consists of creation of a small and vertically oriented gastric pouch with a volume usually less of 30 mL. The upper pouch is completely divided by the gastric remnant and is anastomised to the jejunum, 30–75 cm distally to the ligament of Treitz, thus resulting in an exclusion of a gastric portion to further endoscopic examination [1].

A case of poorly differentiated antral gastric carcinoma with multiple lymph node metastases, in spite of a scarce symptomatology, is described, along with the diagnostic sequence and confounding factors, resulting in a delayed diagnosis and a poor prognosis.

2. Case summary

A 61 year-old white man presented to our day-hospital of Metabolic Diseases because of abdominal distension and breath shortness of one week duration. He had been operated 18 months earlier of laparoscopic RYGB for obesity and lost 30 kg in 1 year, passing from a body mass index (BMI) of 41.8 to 31.7 kg/m2, and thereafter maintained a constant weight while he was in apparent good health and took no medications other than vitamin supplementation. The patient noted a sudden weight gain of 5 kg in few days. His medical history included heavy drinking (100 g alcohol per day) and smoking habit with ca. 30–40 cigarettes daily for more than 30 years. After the RYGB he continued smoking but stopped drinking. He denied nausea, post-prandial discomfort or pain, diarrhoea, constipation, or decreased appetite. He did not refer of any abdominal trauma.

Physical examination revealed the presence of abundant ascites, a large right pleural effusion and a palpable lymph node in the left supraclavicular fossa.

Abdominal paracentesis produced 3000 mL milky-fluid rich in triglycerides, while a total of 1500 mL of citrine pleural fluid was aspirated by thoracentesis.

Transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, and albumin were in a normal range. A CT-scan showed multiple mesenteric and celiac lymphadenopathy with an average diameter of 1 cm. Multiple enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes were also present. No abnormality of the liver or pancreas were reported. Cytologic examination of ascites showed malignant cells.

An incisional left supraclavicular lymph node biopsy was performed and the sample was submitted on paraffin sections for immunochemistry studies with antibodies against several antigens.

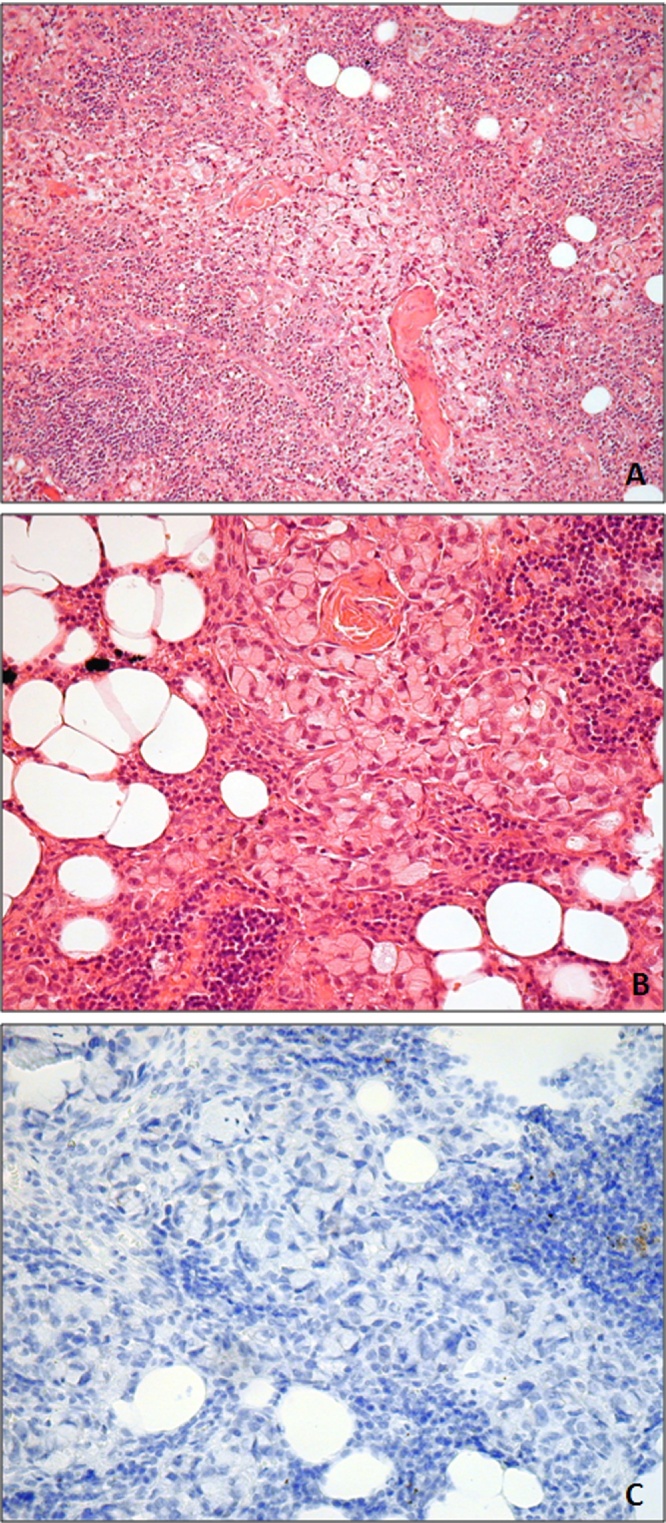

The tumour cells were positive for cytokeratin (CK)7 and CK20, CDX2 and CAM 5.2 immunohistochemistry and negative for HER2 and TTF1 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A.B. Microphotograph of the poorly differentiated carcinoma with signet ring features. C. No immunohistochemistry staining was seen for HER-2- Score 0 (Dako Polyclonal 1:400).

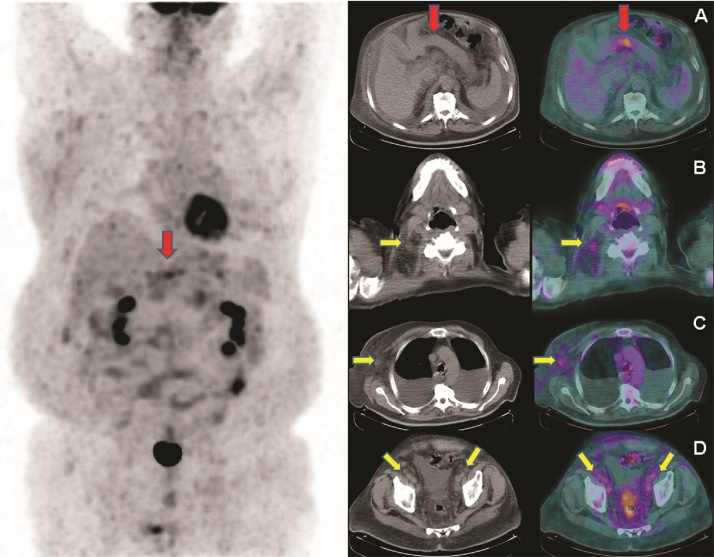

The colonoscopy and the upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy were normal. Bone metastases were excluded by scintigraphy. A CT-scan and positron-emission tomography (PET) with 2-[fluorine-18]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) detected an intense FDG-uptake in the gastric antrum and in the lymph nodal chains (Fig. 2). Given these findings, a diagnosis of poorly differentiated antral gastric carcinoma with multiple lymph node metastases was raised.

Fig. 2.

Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography (18F-FDG PET) image (on the left) showed an area of abnormal increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the epigastrium (red arrow), corresponding to the stomach wall at axial CT and fused PET/CT images (A), respectively. 18F-FDG PET/CT also detected multiple hypermetabolic lymphadenopathies (yellow arrows) in the cervical, thoracic and abdominopelvic regions. In particular left cervical (B), left axillary (C) and bilateral external iliac hypermetabolic lymphadenopathies (D) are showed at axial CT and fused PET/CT images, respectively.

3. Discussion

Obesity prevalence is dramatically increased worldwide and consequently, surgical procedures aimed to induce and maintain weigh loss are largely increasing in the Western Countries, reaching a plauteau of about 113,000 cases per year only in the United States [1]. At the moment, there are no statistical data showing the risk of gastric cancer in the excluded distal stomach after gastric bypass for obesity.

The incidence of gastric cancer in the major part of Western Countries is about 10–15 new cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year, with a median age at diagnosis in the United States of 70 years [3].

A decreasing incidence rate of distal gastric cancer has been observed while tumors in the proximal stomach, i.e. cardia and gastroesophageal junction, are increasing [4]. It is well recognized that Helicobacter pylori infection, dietary habits, smoking, and obesity are risk factors for the development of gastric cancer.

The main manifestation of this clinical case was the presence of a chylous ascites resulting from the accumulation of a milk-like peritoneal fluid as a consequence of intestinal lymph metastasis. Indeed, over two thirds of all cases of chylous ascites are due to abdominal malignancy that metastasize to mesenteric lymph nodes [5]. Primary malignancies which more commonly result in mesenteric lymph nodal involvement include carcinoma of the lung, pancreas, and gastrointestinal tract [5], [6].

The presence of a left supraclavicular lymph node, the so called Virchow’s Node [7], can help the physician identify the visceral origin of the tumor. The gastric origin of the lymph node metastasis in this specific clinical case was unclear on the basis on the immunohistochemistry. Cytokeratin, which forms the intermediate filaments of the cytoskeleton within both normal and malignant epithelial cells, is commonly used as a marker of epithelial cells. The multi-marker phenotype CK20-CK7-CK2 is generally applied to identify colorectal cancer metastasis. Tumor cells expressing positive immunoreactivity to low molecular weight cytokeratin (CAM 5.2), in combination with CK 20, CK 7 is useful to distinguish primary lung carcinoma (CK7+/CK20-) from primary colonic carcinoma (CK7-/CK20+) [8]. Therefore, the indications obtained from the histology of the supraclavicular lymph node were all in favor of a primary colorectal carcinoma.

Great attention, however, should be given to the stomach remnant in RYGB patients, even when the CT scan is negative for mass detection. In fact, since up to 80% of patients are asymptomatic during the early stages of the gastric cancer the diagnosis is often delayed and 2/3 of the cases are discovered only after local invasion is advanced [9]. Abdominal pain, nausea, early satiety and vomiting, associated with weight loss can accompany late-stage gastric cancer. In the present case the symptoms were absent probably because the cancer arose from the excluded stomach and, therefore, there was no contact with food which can cause gastric pain after eating.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the imaging procedure of choice in the diagnosis of gastric carcinoma [10]. Endoscopic ultrasonography is currently the most reliable method for T stage determination, and shows a diagnostic rate between 78% and 93% [11], [12]. In our case the upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy, which could explore only the small gastric pouch and the efferent small bowel limb, was normal and ultrasonography could not have provided helpful images since the cancer site was in the excluded stomach.

Primary tumor location in the stomach can be correctly identified by spiral CT in up to 77% of cases. However, CT is not a good method to differentiate normal lymph nodes from those containing metastases, showing a sensitivity which ranges from 48 to 82% and a specificity lower than 62% [13], [14], [15].

In the present case, contrast enhanced CT was unable to identify the primary gastric cancer. Although PET is considered to be not helpful in T staging because it is a functional imaging modality, here it allowed to detect the primary tumor.

The use of routine preoperative upper GI endoscopy before bariatric surgery is controversial since it can be associated with a relatively high risk in morbidly obese subjects [16]. Although, following the European guidelines that recommend preoperative upper GI endoscopy in all subjects [17], our patient underwent upper GI examination before RYGB, he developed metastatic gastric cancer 18 months after surgery. Indeed, he had a series of risk factors, such as smoking and drinking habits.

Since after RYGB the majority of the stomach is inaccessible to conventional endoscopy, the CT-PET can be very useful for an early diagnosis of a gastric cancer in these patients. Unfortunately, in the staging of gastric cancer, involvement of the supraclavicular lymph node is considered distant metastasis rather and precludes curative surgery and, thus, the diagnosis in our clinical case was done too late to permit the chance of cure. The patient died 4 months after diagnosis.

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

NA.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the wife patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Author contribution

All authors materially participated in the research.

Dr. Capristo and Dr. Mingrone participated in data collection, study design and in article preparation. Dr. Spuntarelli participated in acquisition of patient’ data; Dr. Treglia, Dr. Arena and Prof. Giordano participated in radiological and histological data collection, analysis and interpretation.

All authors have approved the final article.

Registration of research studies

NA.

Guarantor

Esmeralda Capristo, MD.

Geltrude Mingrone, MD.

References

- 1.Livingston E.H. The incidence of bariatric surgery has plateaued in the U. S. Am. J. Surg. 2010;200:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mingrone G., Panunzi S., De Gaetano A. Bariatric-metabolic surgery versus conventional medical treatment in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: 5 year follow-up of an open-label, single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:964–973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krejs G.J. Gastric cancer: epidemiology and risk factors. Dig. Dis. 2010;28:600–603. doi: 10.1159/000320277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devesa S.S., Fraumeni J.F., Jr. The rising incidence of gastric cardia cancer. J. Nat. Cancer Inst. 1999;9:747–749. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.9.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Press O.W., Press N.O., Kaufman S.D. Evaluation and management of chylous ascites. Ann. Intern. Med. 1982;96:358–364. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-3-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aalami O., Allen D.B., Organ C.H. Chylous ascites: a collective review. Surgery. 2000;128:761–778. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.109502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loh K.Y., Yushak A.W. Virchow’s node (Troisier’s sign) N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:282. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm063871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikeda S., Fujimori M., Shibata S. Combined immunohistochemistry of beta-catenin, cytokeratin 7, and cytokeratin 20 is useful in discriminating primary lung adenocarcinomas from metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh T.J., Wang T.C. Tumors of the stomach. In: Feldman M., Friedman L.S., Sleisenger M.H., editors. Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 7th ed. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2002. pp. 829–844. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cappell M.S., Friedel D. The role of esophagogastroduodenoscopy in the diagnosis and management of upper gastrointestinal disorders. Med. Clin. North Am. 2002;86:1165–1216. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(02)00075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly S., Harris K.M., Berry E. A systematic review of the staging performance of endoscopic ultrasound in gastro-oesophageal carcinoma. Gut. 2001;49:534–539. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.4.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willis S., Truong S., Gribnitz S. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the pre-operative staging of gastric cancer: accuracy and impact on surgical therapy. Surg. Endosc. 2000;14:951–954. doi: 10.1007/s004640010040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sussman S.K., Halvorsen R.A., Illescas F.F. Gastric adenocarcinoma: CT versus surgical staging. Radiology. 1998;167:335–340. doi: 10.1148/radiology.167.2.3357941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lakadamyali H., Oto A., Akmangit I. The role of spiral CT in the preoperative evaluation of malignant gastric neoplasms. Tani. Girisim. Radyol. 2003;9:345–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cidón E.U., Cuenca I.J. Gastric adenocarcinoma: is computed tomography (CT) useful in preoperative staging. Clin. Med. Oncol. 2009;3:91–97. doi: 10.4137/cmo.s2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valencia-Flores M., Orea A., Castano V.A. Prevalence of sleep apnea and electrocardiographic disturbances in morbidly obese patients. Obes. Res. 2000;8:262–269. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fried M., Yumuk V., Oppert J.M. Interdisciplinary European guidelines on metabolic and bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2014;24:42–55. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]