Abstract

Objective

To systematically assess the quality of online information related to weight loss that Spanish speakers in the US are likely to access.

Methods

We evaluated the accessibility and quality of information for websites that were identified from weight loss queries in Spanish and compared this to previously published results in English. The content was scored with respect to 5 dimensions: nutrition, physical activity, behavior, pharmacotherapy, and surgical recommendations.

Results

66 websites met eligibility criteria (21 commercial, 24 news/media, 10 blogs, 0 medical/government/university, 11 unclassified sites). Of 16 possible points, mean content quality score was 3.4 (SD=2.0). Approximately 1.5% of sites scored greater than 8 (out of 12) on nutrition, physical activity, and behavior. Unsubstantiated claims were made in 94% of the websites. Content quality scores varied significantly by type of website, (P< 0.0001) with unclassified websites scoring the highest (mean=6.3, SD=1.4) and blogs scoring the lowest (mean=2.2, SD=1.2). All content quality scores were lower for Spanish websites relative to English websites.

Conclusions

Weight loss information accessed in Spanish web searches is suboptimal and relatively worse than weight loss information accessed in English, suggesting US Spanish speakers accessing weight loss information online may be provided with incomplete and inaccurate information.

Keywords: obesity, Hispanics, fat loss, weight reduction, adults

Introduction

In the United States (US), Hispanics have disproportionately greater obesity rates (22.6%) than non-Hispanic Blacks (22.1%), Whites (19.6%), and Asians (11.1%) [1], increasing their risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease [2]. Nationally representative data demonstrate that over 50% of Hispanic women and over 30% of Hispanic men are trying to lose weight [3]. The Internet has become a resource for health and weight loss information and currently, 81% of Hispanics have access to the Internet [4]. National data suggests that 42.83% of Internet users turn to the Web for information on weight loss and physical activity [5]. Limited research exists examining the Internet as a form of quality health communication, but current literature indicates questionable quality and inaccuracy [6]. Health information viewed on the Web has been described as “misleading” [7], “dangerous” [8], “incomplete” [9], and “not evidence-based” [10, 11]. Additional research is needed to investigate the quality of online health information, particularly in Hispanic populations at high risk for obesity [1].

Almost eight in ten online health information inquiries are initiated with a search engine (including Google, Bing, or Yahoo) and only 13% of individuals report starting at a site that specializes in health information, such as WebMD or myplate.gov [12]. However, there is no current measure available for consumers to assess the accuracy of health information provided to Internet users performing online searches. Despite not knowing the accuracy of health data provided through Internet searches, previous work has shown a correlation between the use of online health information and health behavior changes [13, 14]. This is concerning because our previous study showed that the quality of weight loss information English speakers were likely to access on the Internet was poor with respect to the current guidelines for weight loss [15]. Only 4.85% of the evaluated English weight loss information websites scored greater than 8 (of 12 possible points) on the content provided regarding nutrition, physical activity, and behavior changes [15]. The mean content quality score for all weight loss websites in English was 3.75 (of 16 possible points), and the content quality score differed significantly by the type of website [15]. The highest scores were among blogs and medical/government/university websites and the lowest scores were observed among commercial or news/online media sites. However, to our knowledge, the quality of the weight loss information provided in Spanish in the US has not been assessed.

Given that Hispanics are the largest growing sector of the US population [16], the high prevalence of obesity in this population [1], and that 38% of Hispanics in the US report mainly speaking and writing/reading in Spanish [17], it is important to evaluate the quality of weight loss information provided in Spanish on the Internet in the US. The objective of this study was to evaluate the quality and comprehensiveness of the weight loss content that Internet users discover during online searches in Spanish.

Materials and Methods

Search Engine and Browser Selection

The results of an online query are unique to the search engine, and to a lesser extent, the browser that is used. It was necessary to determine which search engine is most commonly used in North America, as algorithmic differences in search engines result in retrieval, archival, and indexing of varying information. StatCounter (Dublin, Ireland) was used to gather statistics relevant to search engine and browser usage on non-mobile devices (e.g., browsers on laptops and desktops). Statistics from this online tool are updated every 4 hours and are based on aggregated, quality-checked data provided by 15 billion page views for more than 3 million websites. Data from StatCounter indicate that as of February 2016, Chrome (Google, Mountain View, CA) is the most utilized browser in North America (46.05%) when compared to other browsers including Internet Explorer (Microsoft, WA; 19.83%) and Safari (Apple, CA; 15.19%). Google is the most commonly used search engine (88.69%) while Bing is used far less frequently (Microsoft; 4.72%), whether on a desktop or a mobile browser. Based on this utilization analysis, all queries in this study were completed using Google on the Chrome desktop browser.

Websites Selection

In order to be able to compare the results of our previously published study [15] with those of this study, we used the same protocol for both studies, albeit with an updated scoring mechanism, to reflect changes in weight loss guidelines since 2013. In particular, we used the same set of queries that were identified in our previously published study [15]. Those queries had been identified and included in the evaluation process as follows. A convenience sample of 20 individuals (9 women, 11 men; 15 Hispanic, 5 White; mean age=39 [SD=9.1] years; 12 graduated high school, 8 had a college degree) was asked for English terms or phrases they would use when searching for information about weight loss on the Internet. Additional keywords were chosen including “weight loss”, “lose weight”, “diet”, and Google’s autocomplete algorithm was used to generate the original query set. A set of 30 distinct English queries were originally generated. For this new study, these queries were then translated by native Spanish speakers. This process resulted in a set of 30 distinct queries in Spanish (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Translated Queries and Corresponding Website

Additionally, it has been previously demonstrated [18] that when performing an online search, roughly 90% of all the clicks occur on the first 5 non-sponsored links. Therefore, after performing each query, we selected the first 5 non-sponsored search engine results pages (SERPs). We also performed a pre-evaluation of the websites generated by the queries and websites that were solely videos (n=13) were excluded from the analysis. Internet forums (n=2) were excluded from our results since introductory forum pages often include a list of links and are too dynamic to assess for content in the context of our study. Additionally, websites that were not relevant to weight loss were also eliminated (n=3). Each website selected was evaluated through assessment of the main page only unless a video was included as support for the main page or if the query was followed by an article spread across multiple pages. This was done to ensure consistency of evaluation across all webpages, which could link to additional information, virtually ad infinitum. Finally, when the analysis was performed by reviewers, an additional 19 websites were eliminated because they were either non-relevant (n=5 websites related to involuntary weight loss due to illness, such as cancer), or the links were no longer active (n=14) since the 30 queries had been performed.

Website Classification

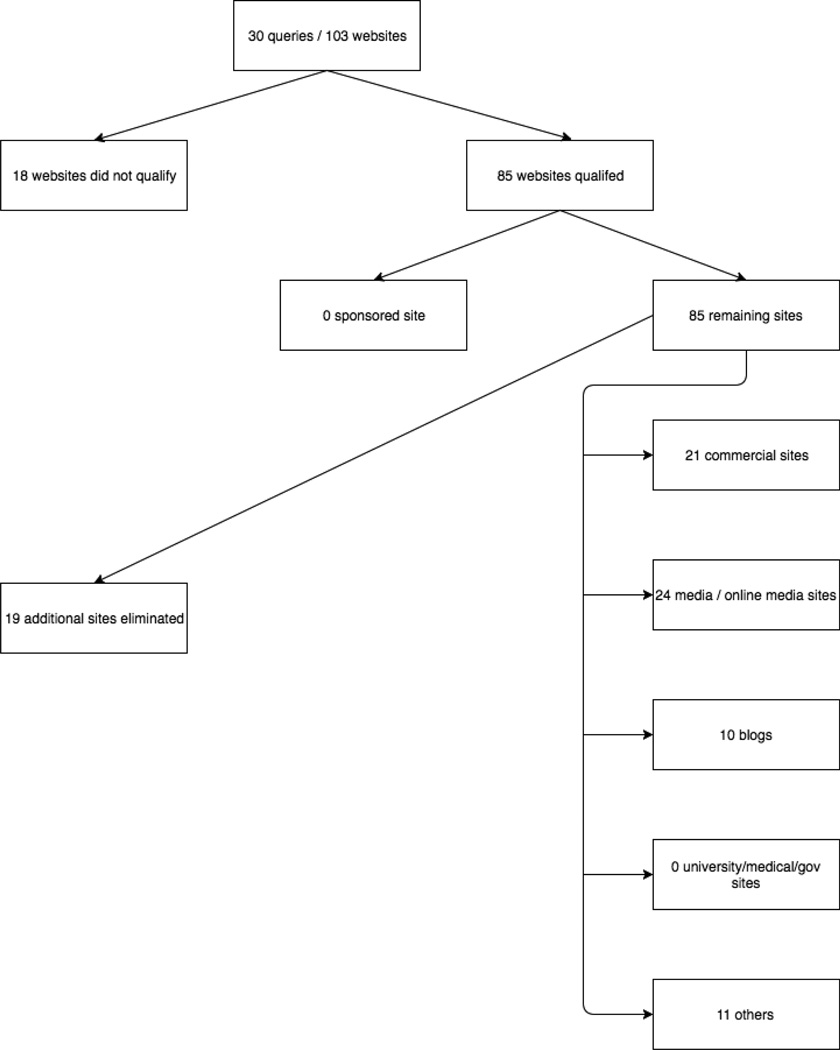

Once websites were identified, they were separated into sponsored and non-sponsored ads (see Figure 1). Sponsored ads were classified as commercial websites and were identified during queries in Google by a light yellow highlight [15]. However, no sponsored ads were found in the queries in Spanish. The remaining non-sponsored websites evaluated were categorized using the standard website nomenclature: commercial sites, news/online media sites, blogs, medical/government/university, and others. Websites were classified as commercial if any products were advertised and sold, but no additional informational content pertaining to weight loss was provided. News/online media site classification included multi-author general press publications. Websites with distinct entries written by a single author or small group of authors in reverse chronological order allowing interaction through comments were classified as blogs. Further, medical/university/government sites were identified as such when doctors and/or healthcare professionals had written the content or when these sites were indicated with a .gov or .edu extension in the Uniform Record Locator (URL). Websites that did not fall into the aforementioned categories were classified as ‘other’ and sometimes included non-profit organizations (n=4 out of 11).

Figure 1.

Inclusion, exclusion and Websites classification

Note. med/uni/gov = medical, university, or government sites

Website Evaluation

Websites were evaluated through adaptation of previous methodology [19, 20]. Each website was evaluated with respect to 3 main dimensions: 1) author credentials; 2) accuracy of information related to weight loss, with respect to aggregated guidelines; and 3) website design.

Scoring criteria for dimensions 1 and 2 remained identical to the scoring instrument developed in [15]. However, the evaluation of content was modified to reflect the current evidence-based literature for weight loss [21–28], including the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans [29], and the significant changes in pharmacotherapy since 2012 (see Table 2). Scores for quality in the nutrition, physical activity, and behavior change components ranged from 0 (nothing) to 4 (excellent) while the pharmacotherapy and surgery options quality scores ranged from 0 (nothing) to 2 (excellent). Scores for nutrition, physical activity, and behavior change were represented with a wider range because pharmacotherapy and surgery options are utilized only in a medical setting and in combined efforts with nutrition, physical activity and behavior change.

Table 2.

Scoring Instrument

| General Website name: |

Date of access: mm/dd/yy | Reviewer’s Initials: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Time Spent Reviewing the Website and Website Type |

|||||

| Start Time: | Finish Time: | Total Time: | |||

| Author/entity a non-profit organization (Yes/No): |

Author/entity a commercial website (Yes/No): |

Author/entity a blog (Yes/No): | |||

| Content | Sub-scores and Total Score | ||||

|

Nutrition Check for the following: 1. Balance energy input/output; 2. A healthy eating pattern includes: a variety of vegetables, fruits, legumes, grains (at least half of which are whole grain), low fat dairy, lean sources of protein, and healthy fats (e.g., plant oils like olive oil and canola oil, nuts, seafood, avocados, and seeds); 3. Limit saturated and trans fat, added sugar (less than 10% of daily calories should come from added sugar), refined grains; and 4. Limit sodium (<2,300 mg per day) |

Content accurately reflects current knowledge pertaining to nutrition: /4 Nothing = 0; Poor = 1; Average = 2; Good = 3; Excellent = 4 Unsubstantiated Claims? Yes/No |

||||

|

Physical Activity Check for the following: 1.150 min/week of moderate activity (e.g. brisk walking); 2.75 min/week of vigorous activity (e.g. running); 3.300 min/week of moderate activity; 4.150 min/week of vigorous activity; and 5. Muscle strengthening of major muscle groups 2 days/week |

Content accurately reflects current knowledge pertaining to physical activity: /4 Nothing = 0; Poor = 1; Average = 2; Good = 3; Excellent = 4 Unsubstantiated Claims? Yes/No |

||||

|

Behavioral Changes Check for the following: 1. Behavioral management activities, such as setting weight-loss goals; 2. Improving diet or nutrition and increasing physical activity; 3. Addressing barriers to change; 4. Self- monitoring; and 5. Strategizing how to maintain lifestyle changes |

Content accurately reflects current knowledge pertaining to behavioral changes: /4 Nothing = 0; Poor = 1; Average = 2; Good = 3; Excellent = 4 Unsubstantiated Claims? Yes/No |

||||

|

Pharmaco-therapy Check for the following: 1) Belviq; 2) Orlistat (xenical or alli if OTC); 3) Saxenda; 4) Contrave (combo of naltrexone and buproprion); 5) Phentermine (combo of adipex and suprenza); 6) Qsymia (phentermine + topiramate); 7) Phendimetrazine; 8) Diethylproprion (Tenuate); and 9) Benzphetamine (Didrex) |

Content accurately reflects current knowledge pertaining to pharmaco-therapy: /2 Nothing = 0; Average = 1; Excellent = 2 Unsubstantiated Claims? Yes/No |

||||

|

Surgical Options Check for the following: Surgery is more effective than nonsurgical treatment for weight loss and control of some comorbid conditions inpatients with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or greater. |

Content accurately reflects current knowledge pertaining to surgical options: /2 Nothing = 0; Average = 1; Excellent = 2 Unsubstantiated Claims? Yes/No |

||||

| Total | /16 | ||||

| Authorship | |||||

| Identifiable author/entity |

Authority of the author/entity |

Credential of the author/entity are listed |

Author/entity is a university |

Author/entity of government or state organization |

Contact information provided |

| Yes = 1; No = 0 | Yes = 1; No = 0 | Yes = 1; No = 0 | Yes = 1; No = 0 | Yes = 1; No = 0 | Yes = 1; No = 0 |

| Total | /6 | ||||

| Design | |||||

| Distinguishable structure (header/body/footer) |

Appropriate font/background color |

Use relevant and adequate graphics |

Minimal page layering (added links) |

Page is ad-free | Main text is ad- free |

| Yes = 1; No = 0 | Yes = 1; No = 0 | Yes = 1; No = 0 | Yes = 1; No = 0 | Yes = 1; No = 0 | Yes = 1; No = 0 |

| Total | /6 | ||||

| Total Score | /28 | ||||

Authorship was scored based on criteria (6-point scale) that included whether the author was identifiable, whether they had a degree in a related field, affiliate organization, and whether contact information was available. A design criterion (6-point scale) was based on formatting of the webpage (i.e., structure, minimal page layering, and minimal ads).

We scored whether the websites contained references that were hyperlinked and reputable (i.e., published material in a peer-reviewed journal or written by an authoritative source such as a registered dietitian or physician). We commented as to when the website was last updated and whether or not any unsubstantiated claims were included in the content. Unsubstantiated claims were defined as any weight loss recommendations that did not fall in line with the current evidence-based recommendations [21–29]. Scoring was not affected by unsubstantiated claims.

Procedures

A set of 30 queries in Spanish was generated as described earlier in this paper. The queries were then performed on February 3, 2016 using Google on a desktop computer, and generated a set of 103 distinct websites (see Table 1). The websites were assessed for inclusion and exclusion criteria and then distributed to the research team. The team met to discuss the scoring instrument and to pilot test it prior to performing the study. Three investigators, all Spanish native speakers (MC, SC, EP) then independently scored each website using our scoring instrument (see Table 2) between February and April 2016.

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tools hosted at the University of Florida. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for importing data from external sources [30].

Statistical Analyses

The scores were averaged across investigators for subscale and total scores. Inter-rater reliability was also determined using Krippendorff’s Alpha Reliability Estimate. Descriptive statistics were reported as mean ± SD and the scores were compared between types of websites using a 2-sided Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test. All the analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). It is considered of statistical significance if P-value ≤ 0.05.

Results

Selected Queries and Websites

The 30 selected queries were translated into Spanish by native speakers (MC, SC, EP) and resulted in the identification of 103 unique sites (see Figure 1). In a preliminary analysis, we excluded sites that were considered Internet forums, videos, or purely advertising pages (n=18). Of the 85 sites remaining, an additional 19 sites were removed from the analyses as they were either not relevant (e.g. involuntary weight loss due to illness), or had been taken down. The remaining 66 websites included 21 commercial sites, 24 news/online media sites, 10 blogs, and 11 unclassified sites. There were no medical, university, or government websites returned by any of the queries.

Nutrition, Physical Activity, Behavior Change, Pharmacotherapy, and Surgery Content Sub-scores

For all sites (see Table 3), the content quality sub-score (all content dimensions include a maximal score of 4) for nutrition was mean=1.5, (SD=0.7); physical activity mean=1.0, (SD=0.9); behavioral change mean=0.9, (SD=0.8); pharmacotherapy mean=0.0, (SD=0.1); and surgery mean=0.0, (SD=0.0). When looking specifically at the sub-score with respect to nutrition, physical activity and behavior change, only 1.5% of websites attained a score of 8 or higher and only 12% of pages scored 6 or higher (maximal score of 12). Nutrition sub-scores were the highest of the content sub-scores. Very few sites mentioned pharmacotherapy options (n=5) or surgery options (n=1), which is consistent with what was observed in [15], since medical supervision is necessary with respect to these dimensions.

Table 3.

Mean Sub-scores and Total Score by Type of Website

| Content Sub-scores | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition (Range = 0–4) |

Physical Activity (Range = 0–4) |

Behavioral (Range = 0–4) |

Pharmaco-therapy (Range = 0–2) |

Surgery (Range = 0–2) |

Content (Range = 0–16) |

Authorship (Range = 0–6) |

Design (Range = 0–6) |

Total Score (Range = 0–28) |

|

| All sites (n = 66), mean SD |

1.5 (0.7) | 1.0 (0.9) | 0.9 (0.8) | 0.0 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 3.4 (2.0) | 0.8 (0.8) | 4.2 (0.9) | 8.5 (2.8) |

| Commercial (n = 21), mean SD |

1.5 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.9) | 0.9 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.1) | 3.5 (1.8) | 0.8 (0.7) | 4.1 (0.9) | 8.4 (2.5) |

| News/media (n = 24), mean SD |

1.3 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.6) | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.0 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 2.5 (1.4) | 0.8 (0.8) | 4.1 (0.8) | 7.4 (2.3) |

| Blog (n = 10), mean SD |

1.0 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 2.2 (1.2) | 0.5 (0.6) | 4.2 (0.9) | 6.9 (1.3) |

| Med/uni/gov (n = 0), mean SD |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Unclassified (n = 11), mean SD |

2.2 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.8) | 2.0 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6.3 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.1) | 4.8 (0.5) | 12.4 (1.3) |

| P | .0009 | .0004 | < .0001 | 0.46 | 0.54 | < .0001 | 0.27 | 0.08 | < .0001 |

Note. Med/uni/gov = medical, university, or government sites. P values are based on Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test.

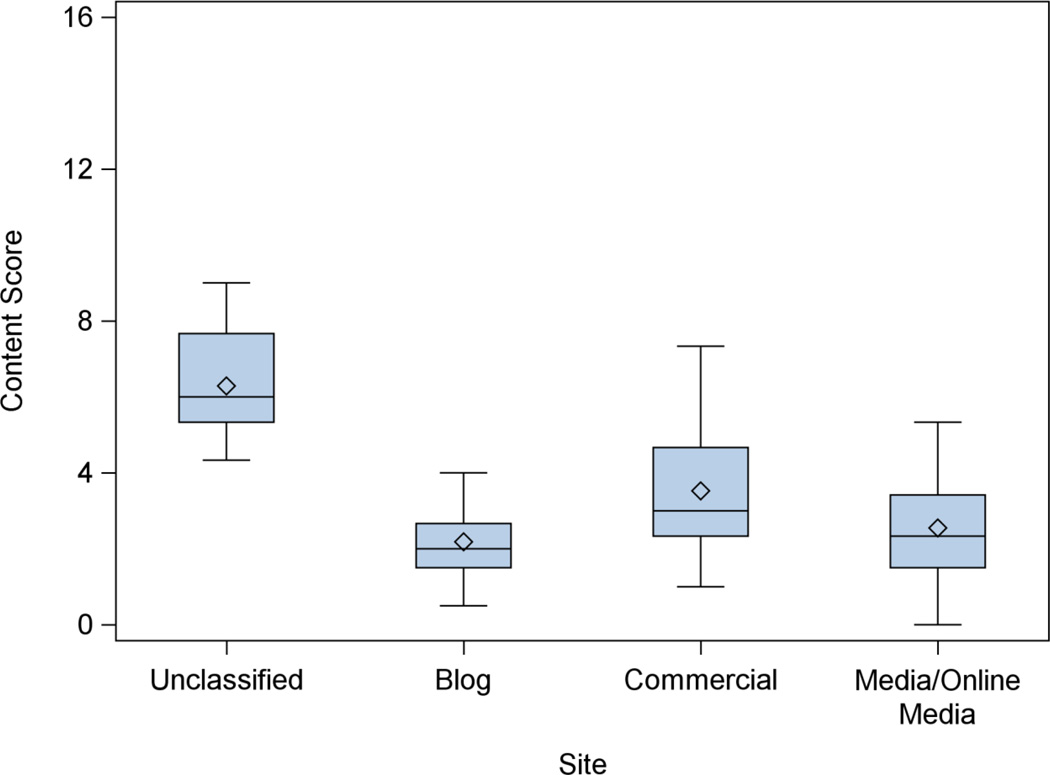

For all websites, the mean content quality sub-score (maximal score of 16) was 3.4 (SD=2.0) (see Table 3). The content quality sub-score varied significantly by the type of website (see Table 3 and Figure 2): the highest content sub-scores were among our unclassified group (mean=6.3, SD=1.4), while the lowest content sub-scores were blogs (mean=2.2, SD=1.2, P<0.0001). The mean design quality sub-score (maximal score of 6) was 4.2 (SD=0.9).

Figure 2.

Content scores per Website type

Note. medical, university, or government sites (n=0) not included in figure

For all websites, the mean total quality score (maximal score of 28) was 8.5 (SD=2.8) (see Table 3). The mean total quality score varied significantly by the type of website (see Table 3): the highest scores were among our unclassified group (mean=12.4, SD=1.3), while the lowest scores went to blogs (mean=6.9, SD=1.3, P<0.0001).

Reputable references were provided for only 45% of websites, with 68% providing hyperlinks. 73% of sites included a date that the site was last updated. Unsubstantiated claims with respect to the guidelines used in the scoring instrument were made in 94% of websites, particularly regarding nutrition (in 100% of the websites with unsubstantiated claims), physical activity (in 47% of the websites with unsubstantiated claims) and behavior change (in 39% of the websites with unsubstantiated claims) information. In websites with unsubstantiated claims, only 10% were related to pharmacotherapy options and none were related to surgery options. The Krippendorff’s Alpha Reliability Estimate was 0.66 for the content, which indicated moderate agreement among the reviewers on the exact scores for the content.

Discussion

This investigation focused on the quality of content that Internet users performing weight loss online searches in Spanish are likely to access, and descriptively compared the results with those of a previously published study [15] where the queries were performed in English. The primary result of this study shows that the quality of information related to weight loss that Spanish speakers in the US are likely to access is poor. Additionally, this data suggests that not only is the information in Spanish of substandard quality, it is also of lower quality than that available in English.

This evaluation protocol evaluated 5 content dimensions. However, most websites are more likely to address weight loss from a self-management perspective, e.g. nutrition, physical activity, and behavior. To address a possible floor effect in the scoring methodology, scores were analyzed with respect to these 3 components as a summation score and a low quality of information was observed, with only 12% of Spanish pages scoring over 6 (out of 12) with respect to these criteria (versus 23% of websites in English [15]), and only 1.5% scoring 8 (out of 12) or higher. These results demonstrate that nutrition, physical activity, and behavior change information for weight loss from search engines is remarkably suboptimal in Spanish, even more so than in English.

Another particularly interesting result in this study was the complete absence of medical, university-based, and governmental websites in our queries, which comprised about 13.5% of the websites evaluated in our English study [15]. The medical, university-based, and government websites that were observed in English typically provided evidence-based information and often scored well. The lack of these websites in the Spanish query was surprising given the availability of federal websites in both English and Spanish, as well as the existence of several Spanish-speaking universities. Interestingly, myplate.gov did not appear in the results here nor did it appear in the results of the English study [15].

Although blogs scored relatively well in [15], they scored poorly in this study. It was previously observed that weight loss blogs are usually written by authors with a keen interest in health, and although they did write unsubstantiated claims with respect to weight loss guidelines, they also presented somewhat accurate information on nutrition, physical activity, and behavioral changes for weight loss [15]. This does not seem to be the case with Spanish blogs, as most of them seemed to refer to other sites that were commercial in nature and provided very low quality information.

It is not clear at this stage why the information for weight loss that is likely to be accessed by Spanish speakers in the US is lower than the already substandard information in English. However, this may largely be a consequence of search engine optimization (SEO) techniques used in websites, which can be a result of primarily commercial Spanish-speaking websites investing on SEO to ensure that their sites nearly always top online searches. Given the large segment of the US population that favors Spanish, which also faces high obesity rates [1], it is critical that organizations provide evidence-based information for weight loss in Spanish and improve their websites with SEO in order to ensure that Spanish speakers are able to access quality advice on weight loss.

This study had several strengths and limitations. It did not look at the quality of information generated by search engines used on mobile devices. When performing a Google search, results vary from mobile to non-mobile. Therefore, it is possible that information on mobile devices could be of higher or lower quality. Additionally, this study is limited to Internet searches. However, social media also provides information on weight loss, which may differ from what was observed in this study. Finally, the Krippendorf’s Alpha of 0.66 suggests only moderate agreement between raters. However, since the scores are low to very low, a moderate agreement between scorers does not weaken the main result of the paper, which is that the information for weight loss in Spanish and likely accessed by users is of substandard quality.

The strengths of this study include its focus on the information that Spanish-speaking Internet users in the US are likely to access in the first 5 SERP links, which are the links they are most likely to access [18]. Given that Hispanics are the largest growing sector of the US population [16], have a high prevalence of obesity [1], and that 38% of Hispanics in the US report mainly speaking and writing/reading in Spanish [17], this study examined weight loss search engine results that pertain to a very relevant segment of the population. This study does not suggest that no quality information in Spanish is available through online searches. A cursory review of pages further down SERPs suggests there is quality information available, usually in page 3 or further in a Google search. However, as previously noted [18], it is highly unlikely that a significant portion of Internet users access this information. Additionally, the scoring criteria for content was updated from the original manuscript [15] to reflect the updated literature and recommendations for weight loss, including the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the significant changes in pharmacotherapy since 2012. Thus, it was not practical to conduct a statistical analysis to test for differences between the results in English and Spanish weight loss search engine results due to changes in the grading rubric. Nonetheless, with only 1.5% of websites in Spanish scoring above 8 (out of 12) on nutrition, physical activity, and behavior change, and 12% scoring above 6 (out of 12) versus 4.85% and 25% respectively in English, the results suggest that websites in Spanish provide weight loss information with quality and content that is well below that of English websites.

Conclusions

In the US, Hispanic persons have disproportionately greater obesity rates than non-Hispanic Blacks, Whites, and Asians [1]. Nationally representative data demonstrate that over 50% of Hispanic women and over 30% of Hispanic men report trying to lose weight, often turning to the Web for information on weight loss [5]. We demonstrate that in the US, weight loss information accessed through online searches in Spanish is suboptimal and relatively worse than the quality of weight loss information accessed through online searches in English. This suggests that Hispanic persons accessing weight loss information via search engines in Spanish may be accessing incomplete and inaccurate information about weight loss, potentially influencing the disproportionate prevalence of obesity in Hispanic persons in the US. In order to increase the likelihood of access to higher quality weight loss information for the Spanish-speaking Hispanic population, medical/government/university organizations should strive to make their websites available in Spanish and improve search engine optimization to ensure their websites appear as top searches pertaining to weight loss.

Study Importance Questions.

- What is already known about this subject?

-

◦Less than 75% of websites in English search engine results scored better than 6 out of 12 for accuracy of weight loss information

-

◦Medical, government, or university sites and blogs scored the highest in English search engine results for accuracy of weight loss information

-

◦Commercial or news/media sites scored the lowest in English search engine results for accuracy of weight loss information

-

◦

- What does your study add?

-

◦Only 12% of websites in Spanish search engine results scored better than 6 out of 12 for accuracy of weight loss information

-

◦No medical, government, or university sites appeared in our Spanish search engine results for accuracy of weight loss information

-

◦Unclassified sites scored the highest and blogs scored the lowest for accuracy of weight loss information in Spanish search engine results

-

◦

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported in part by the Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) at University of Florida and includes the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant UL1 TR001427. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH or any other organization.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reilly JJ, et al. Health consequences of obesity. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2003;88(9):748–752. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.9.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaemsiri S, Slining MM, Agarwal SK. Perceived weight status, overweight diagnosis, and weight control among US adults: the NHANES 2003–2008 Study. Int J Obes. 2011;35(8):1063–1070. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pew Research Center. [Accessed May 16, 2016];Americans' Internet Access: 2000–2015. 2015 Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/06/26/americans-internet-access-2000-2015/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCully SN, Don BP, U JA. Using the Internet to Help With Diet, Weight, and Physical Activity: Results From the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e148. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cline RJ, Haynes KM. Consumer health information seeking on the Internet: the state of the art. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(6):671–692. doi: 10.1093/her/16.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLeod SD. The quality of medical information on the Internet. A new public health concern. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116(12):1663–1665. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.12.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKinley J, Cattermole H, Oliver CW. The quality of surgical information on the Internet. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1999;44(4):265–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silberg WM, Lundberg GD, Musacchio RA. Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the Internet: Caveant lector et viewor--Let the reader and viewer beware. Jama. 1997;277(15):1244–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pereira J, Bruera E. The Internet as a resource for palliative care and hospice: a review and proposals. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;16(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandolfini C, Impicciatore P, Bonati M. Parents on the web: risks for quality management of cough in children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1):e1. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pew Research Center. [Accessed May 16, 2016];Information Triage. 2013 Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/15/information-triage/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleisher L, et al. Relationships among Internet health information use, patient behavior and self efficacy in newly diagnosed cancer patients who contact the National Cancer Institute's NCI Atlantic Region Cancer Information Service (CIS) Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium. 2002:260–264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tate DF, Wing RR, Winett RA. Using Internet technology to deliver a behavioral weight loss program. JAMA. 2001;285 doi: 10.1001/jama.285.9.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modave F, et al. Analysis of the Accuracy of Weight Loss Information Search Engine Results on the Internet. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(10):1971–1978. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United States Census Bureau. [March 15, 2014];Profile American Facts for Features. 2013 Available from: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb13-ff19.html.

- 17.Center.;, P.R. A majority of English-speaking Hispanics in the U.S. are bilingual. [Accessed May 16, 2016];2015 Available from: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/03/24/a-majority-of-english-speaking-hispanics-in-the-u-s-are-bilingual/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan B, et al. In Google We Trust: Users’ Decisions on Rank, Position, and Relevance. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2007;12(3):801–823. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abbott VP. Web page quality: can we measure it and what do we find? A report of exploratory findings. J Public Health Med. 2000;22(2):191–197. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/22.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pealer LN, Dorman SM. Evaluating health-related Web sites. J Sch Health. 1997;67(6):232–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1997.tb06311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51s–209s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villareal DT, et al. Obesity in older adults: technical review and position statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity Society. Obes Res. 2005;13(11):1849–1863. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wadden TA, et al. Lifestyle modification for obesity: new developments in diet, physical activity, and behavior therapy. Circulation. 2012;125(9):1157–1170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donnelly JE, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z, et al. Meta-analysis: pharmacologic treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(7):532–546. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rucker D, et al. Long term pharmacotherapy for obesity and overweight: updated meta-analysis. Bmj. 2007;335(7631):1194–1199. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39385.413113.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maggard MA, et al. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(7):547–559. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yermilov I, et al. Appropriateness criteria for bariatric surgery: beyond the NIH guidelines. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(8):1521–1527. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris PA, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]