INTRODUCTION

Among patients diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus (BE), an asymptomatic precursor lesion, the annual incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is estimated to be 0.2%–0.6%1–3. Consensus guidelines recommend routine surveillance esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) every 3–5 years for patients with BE, according to presence and degree of dysplasia1–3. Surveillance guidelines published in November 2015 by the American College of Gastroenterology now recommend individualized discussions about risks and benefits of BE surveillance considering age, likelihood of survival over the next 5 years, and ability to tolerate potential interventions1. Considering life expectancy when counseling patients about the significance of BE has not been emphasized by other surveillance guidelines1. Older men are at greater risk for BE diagnosis than women, but we are unaware of any studies of the life expectancy distribution of older men diagnosed with BE1–3. Understanding life expectancy of those diagnosed with BE would address the importance of all guidelines including statements about individualized surveillance decisions that consider life expectancy.

METHODS

We conducted a national, cross-sectional study of 4,252 male veterans ≥ 65 years who received a new BE diagnosis in 2011 to calculate their estimated life expectancy. These veterans had an outpatient visit in 2011 at 104 Veteran Affairs (VA) facilities and were diagnosed with incident BE (based on ICD 9-CM code 530.85) in VA National Patient Care Database or Medicare between 1/1/11-12/31/11. A chart validation of this algorithm for identifying incident BE using VA claims data had a positive predictive value >93%4. We excluded men enrolled in Medicare managed care and those with history of BE, decompensated liver disease, metastatic cancer, or other diseases of the esophagogastric region within 5 years preceding BE diagnosis.

Age was determined on the date of BE diagnosis. The Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index (CCI) was calculated from VA and Medicare inpatient and outpatient claims during the preceding 12 months and is highly predictive of mortality5. Men were categorized into mutually exclusive life expectancy groups: 1) “limited” life expectancy (< 5 years) for those age ≥ 85 and CCI ≥ 1 or age ≥ 65 and CCI ≥ 4; 2) “favorable” life expectancy (> 10 years) for those age 65–74 and CCI=0; or 3) “intermediate” life expectancy for everyone else. Mortality was based on the VA Vital Status file.

RESULTS

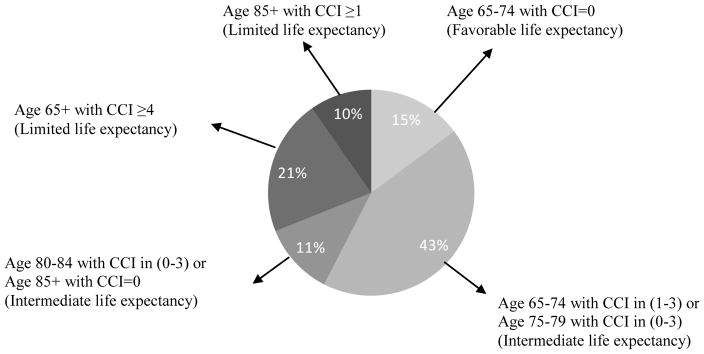

Consistent with an older male veteran population, 94% were white, 71% were married and 42% lived in the South. Over 25% were >80 years at the time of BE diagnosis and more than 25% had CCI ≥ 4 (Table). 1,322 patients (31%) had limited life expectancy at the time of BE diagnosis while 629 (15%) had favorable life expectancy (Figure). 1,086 patients (26%) died within 4 years after BE diagnosis including 44% with limited life expectancy and 8% with favorable life expectancy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants (N=4,252)

| Characteristic | Total Cohort (N=4,252) N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| 65–69 | 1,355 (31.9) |

| 70–74 | 895 (21.0) |

| 75–79 | 903 (21.2) |

| 80–84 | 628 (14.8) |

| ≥85 | 471 (11.1) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 4,013 (94.4) |

| Black | 145 (3.4) |

| Hispanic | 15 (0.3) |

| Other/Unknown | 79 (1.9) |

| Marrieda | |

| No | 1,229 (29.1) |

| Yes | 2,993 (70.9) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index Score | |

| 0 (good health) | 972 (22.9) |

| 1–3 (average health) | 2,196 (51.6) |

| ≥4 (poor health) | 1,084 (25.5) |

| Census Region | |

| Midwest | 1,007 (23.7) |

| Northeast | 750 (17.6) |

| South | 1,794 (42.2) |

| West | 701 (16.5) |

| Lived in ZCTA in which ≥ 25% of Adults had a College Educationb | |

| No | 2,405 (57.5) |

| Yes | 1,776 (42.5) |

| Median Annual Income of ZCTAb | |

| Highest Tertile (≥ $56,728) | 1,396 (33.4) |

| Middle Tertile (>$43,494–$56,728) | 1,391 (33.3) |

| Lowest Tertile (≤ $43,494) | 1,392 (33.3) |

| Life Expectancyc | |

| Favorable | 629 (14.8) |

| Intermediate | 2,301 (54.1) |

| Limited | 1,322 (31.1) |

Marital status was abstracted from the Veterans Affairs National Patient Care Database. Data were missing for 0.9% of men in the cohort.

ZCTA=Zip Code Tabulation Area. Through linkage to the 2011 US Census, we determined the percentage of adults with a college degree who lived within a Veteran’s ZCTA and the median income for adults who lived within that ZCTA. Data on education and income were missing for 1.7% of men in the cohort.

Life expectancy estimates were based on combining age and Charlson Comorbidity Index Scores.

Figure. Many Older Veterans Diagnosed with Barrett’s Esophagus Have Limited Life Expectancy (N=4,252).

CCI=Charlson Comorbidity Index Score

= favorable life expectancy — potential benefits may outweigh potential harms from BE surveillance;

= favorable life expectancy — potential benefits may outweigh potential harms from BE surveillance;

= intermediate life expectancy —unclear if potential benefits outweigh potential harms from BE surveillance;

= intermediate life expectancy —unclear if potential benefits outweigh potential harms from BE surveillance;

= limited life expectancy — potential harms outweigh potential benefits from BE surveillance.

= limited life expectancy — potential harms outweigh potential benefits from BE surveillance.

DISCUSSION

This is the first national study to determine the distribution of life expectancy among a large cohort newly diagnosed with BE during routine clinical practice. Nearly a third of older veterans diagnosed with BE had limited life expectancy, suggesting they are more likely to experience harms of surveillance than benefit from detection of dysplasia or early cancer. Randomized control trial data about benefits of BE surveillance are lacking while studies show EGD harms increase with age and illness, including respiratory distress, bleeding, cardiovascular events and psychological distress1–3,6. While generalizability of our findings to older women and non-veterans is unclear, our findings suggest many older adults are diagnosed with BE during the last few years of life. All guidelines should emphasize the importance of avoiding BE surveillance in those with limited life expectancy, which will reduce unnecessary procedures and complications emanating from incidental diagnosis of this asymptomatic condition.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (K24AG041180) to Dr. Louise Walter.

Footnotes

Meeting Presentation: This project was presented at the Annual American College of Gastroenterology Meeting in 2015.

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: The six listed authors were the sole contributors to this manuscript. Drs. Ko and Walter are responsible for all of the study; Dr. Shergill, and Ms. Espaldon were involved in study design and critical revision of the manuscript; Dr. Shi and Ms. Fung were involved in statistical study design, analysis, and critical revision of the manuscript. As corresponding author, Dr. Walter had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Drs. Ko and Walter are responsible for all aspects of the study; Dr. Shergill, and Ms. Espaldon were involved in study design and critical revision of the manuscript; Dr. Shi and Ms. Fung were involved in statistical study design, analysis and critical revision of the manuscript.

Sponsor’s Role: The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of this study or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:30–50. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gut. 2014;63:7–42. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Gastroenterological Association. Spechler SJ, Sharma P, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1084–1091. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shakhatreh MH, Duan Z, Kramer J, et al. The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in a national veterans cohort with Barrett’s Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1862–1868. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monkemuller K, Fry LC, Malfertheiner P, et al. Gastrointestinal endoscopy in the elderly: Current issues. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:821–827. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]