Abstract

Objectives

To identify predictors of hospital inpatient admission of older Medicare patients following discharge from the emergency department.

Design

Retrospective cohort study

Setting

284 non-federal California hospitals

Participants

505,315 visits of patients age >65 years (yrs) with Medicare insurance discharged from California EDs in 2007.

Measurement

Using the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development files, predictors of a hospital inpatient admission within 7 days of ED discharge in older adults (age > 65 yrs) with Medicare were evaluated.

Results

Hospital inpatient admissions within 7-days of ED discharge occurred in 23,340 (4.6%) visits and were associated with older age (Age 70–74 Adjusted Odds Ration=AOR 1.12, 95% Confidence Interval=CI 1.07–1.17; Age 75–79 AOR 1.18, 95% CI 1.13–1.23; Age 80+ AOR 1.4, 95% CI 1.35–1.46), skilled nursing facility use (AOR 1.82, 95% CI 1.72–1.94), leaving the ED against medical advice (AOR 1.82, 95% CI 1.67–1.98), and the following diagnoses with the highest odds of admission: End Stage Renal Disease (AOR 3.83, 95% CI 2.42–6.08), chronic renal disease (AOR 3.19, 95% CI 2.26–4.49), and congestive heart failure (AOR 3.01, 95% CI 2.59–3.50).

Conclusion

A total of 4.6% of older adults with Medicare insurance have a hospital inpatient admission after discharge. Chronic conditions such as renal disease and heart failure were associated with the greatest odds of admission.

Keywords: Emergency department, Medicare, outcomes

INTRODUCTION

An emergency department (ED) visit for episodic illness may lead to fragmented care management for older adults.1,2 Contributing factors may include pressure to rapidly discharge patients who do not require hospitalization, incomplete knowledge about a specific patient’s complex medical needs, and limited resources to coordinate post-ED care with primary care physicians, specialists, home health services, and other health care providers. Unscheduled hospital admissions shortly after an ED evaluation and discharge may signal opportunities to improve care. Such events may signal a missed diagnosis of a serious illness, incomplete ED care, or insufficient coordination of outpatient care associated with the initial ED visit. Understanding the factors associated with short-term admissions after ED discharge in older adults should help ED practitioners, geriatricians, and policy makers better care for this population.

To our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating the factors associated with admission within 7 days of ED discharge in older Medicare patients. There is a concern that in older adults, age, rather than the diagnosis drives this outcome. The objective of this study was within older Medicare patient visits (age > 65 years), to identify the incidence and predictors of admissions within 7 days of ED discharge to non-federal California hospitals. The study hypothesis was that the predictors of admission in this cohort were driven by diagnosis rather than age.

METHODS

Design and Setting

A retrospective cohort study of ED visit discharges from general, acute, non-federal hospitals in California in 2007 was conducted. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the California Committee for Protection of Human Subjects and the Institutional Review Board of the University of California at Los Angeles.

Data Sources

All non-federal healthcare facilities in California are required to provide ED and hospital discharge data to the Office of Statewide Hospital Planning and Development (OSHPD).3 OSHPD non-public use files for all ED visits resulting in discharge (the ED file) and unscheduled hospital admissions (the Patient Discharge File) for general, acute-care hospitals were obtained. The ED file was linked to the Patient Discharge File based on date of birth, gender, and a unique identifier (Record Linkage Number) that is a masked Social Security number. The ED file also provided the following clinical variables: primary diagnosis, other diagnoses at the time of the visit, principal procedure, and other procedures. Hospital-level financial and structural data were extracted from the year 2007 OSHPD public-use files. The non-public use files supplied the patient characteristic variables such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, and insurance status. The public use files provided the hospital characteristic variables such as ownership, teaching affiliation, and hospital beds. All variables had a less than 3% missing rate.

Participants

The analysis was of older adult (age ≥65 years) patient ED visits that resulted in emergency department discharge in 2007. Exclusion criteria included index visits to facilities that closed their hospital or ED in 2007, index visits to hospitals without basic or comprehensive emergency services, and index visits to children’s hospitals. Index visits without a Record Linkage Number were also excluded because of the inability to match to subsequent hospital admissions. Visits with a disposition of death in the ED and transfer to an acute care facility or to hospice care were similarly excluded. Multiple ED visits by the same patient on the same day as well as ED visits with a hospital admission by the same patient on the same day were also excluded based on the team’s prior work that suggested that these may reflect duplicate coding for a single visit.4 Finally, ED visits occurring in the last week of 2007 were also excluded because of the lack of complete 7-day follow-up data.

Outcome Measures

The outcome was an unscheduled admission to an inpatient hospital bed within 7 days after ED discharge. The inpatient admission did not have to originate from a particular visit such as the emergency department. A 7-day time frame was selected based on prior studies of adverse events after ED discharge5–8, local quality improvement efforts that often track 7-day admissions, and an assumption by the research team that longer time frames were likely to include an increasing proportion of events unrelated to the index ED visit. If there were more than one ED visits in the seven days prior to an admission, then the outcome was attributed to only the most recent ED visit.

Candidate Predictors

Hospital-level characteristics included in the model were ownership (not-for-profit, for-profit, and government), trauma center status, teaching affiliation, and size of hospital (based on the number of medical and surgical beds:<100 or>100). There was no missing data for hospital characteristics. All predictors were chosen based on prior literature and the team’s conceptual model.

Visit-level information of the ED visit including age, sex, race/ethnicity and day of week (weekday or weekend) of the ED visit were assessed. A dichotomous variable was created to identify ED visits with a disposition of either having left the ED‘ Against Medical Advice (AMA)’ and signing a document stating that they do not agree to the disposition plan of the physician or ‘eloped’, which describes patients who leave the ED without permission before a final management plan has been made. Patients coming to the ED from a skilled nursing facility or not were also identified.

Finally, information on the primary ED discharge diagnosis was collected. Primary International Statistical Classification of Disease (ICD) diagnosis codes were obtained from emergency department encounters and were then sorted into 36 categories. There were a total of thirty-seven diagnosis codes considered for each visit. Thirty-five of the diagnoses were based on a classification system previously described.4 In creating this classification system, all possible ICD-9 codes were mapped to the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality Clinical Categorization Software (CCS)9 multi-level diagnosis codes. A multi-specialty team of physicians further aggregated the codes into categories based on clinical coherence and relevance to the ED. Two codes did not map out solely to CCS codes: End stage renal disease (ESRD) was identified with ICD-9 codes and chronic renal disease (CRD) was identified by subtracting the ESRD ICD-9 codes from the CCS for renal disease.

Data Analysis

First, the cohort from the base population was selected. Then, the team assessed individual predictors using the hospital-level random-effects model for continuous variables and the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by hospital for categorical variables. The outcome was modeled using hierarchical logistic regression with ED visits clustered within hospitals; all models included a hospital-level random effect. All other candidate predictors were included as fixed effects.

The adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) estimates from the model were generated. The reference group used was age of 65–69 years, male, white, weekday, no AMA/elope, not a Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) resident, ED diagnosis category= ‘Hypertension’; not-for-profit, non-teaching, non-trauma center. The most common and 2nd most common subsequent inpatient diagnosis for a given emergency department discharge diagnosis was also reported. This included the percent of the time the most common inpatient diagnosis was the same as the ED discharge diagnosis. Data analyses were performed with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Subjects

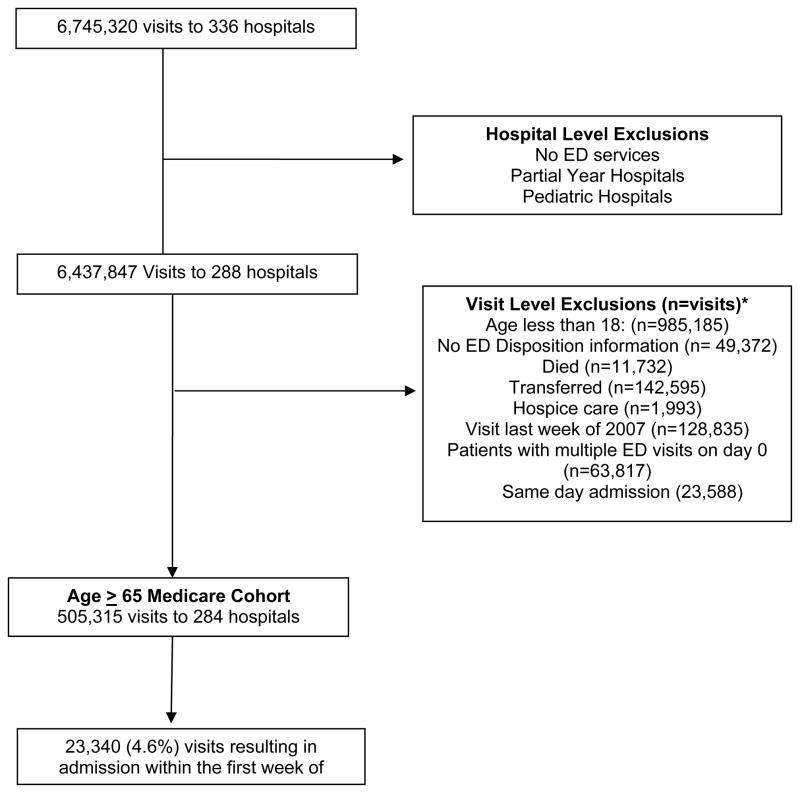

Figure 1 illustrates the construction of the study cohort. The cohort contained a total of 505,315 ED visits that were discharged from 284 facilities in 2007 by Medicare patients age > 65 years. There were 23,340 (4.6%) patient visits that resulted in an inpatient admission within 7 days of being discharged from the ED. Of the 23,340 in patient admissions, 21,920 (94%) were attributed to unique patients.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of study cohort.

*Multiple patients with more than 1 exclusion

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the cohort. The mean age of patients who were admitted within 7 days was 78.6 years (Standard Deviation=SD 8.1) and that of the controls was 77.5 years (SD 8.1). Table 2 shows the primary discharge diagnoses of the cohort stratified by outcome. The two diagnoses that resulted in highest odds of an admission involved renal impairment and were End Stage Renal Disease and chronic renal disease. The most common discharge diagnosis was “other injuries”, which includes burns, wounds and superficial injuries (13.9% of all discharge diagnoses in older adult cohort). However patients with this diagnosis were rarely admitted within 7 days. In the subset of patients who experienced the outcome, the most common and 2nd most common subsequent primary inpatient diagnoses associated with each ED primary discharge diagnosis (Online Appendix A) are provided. Of the ED discharge diagnoses, 72% were the same as the most common primary inpatient diagnosis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Cohort

| Facilities (n=284) | Total Visits (%) (n=505,315) | Admitted within 7-days (n=23,340) | Not Admitted within 7-days (n=481,975) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hospital Characteristics

| |||||

| Ownership | 0.0003 | ||||

| Not-For-Profit | 204 | 400,194 (79) | 18,463 (79) | 381,731 (79) | |

| For-Profit | 63 | 83,817 (17) | 3,998 (17) | 79,819 (17) | |

| County | 17 | 21,304 (4) | 879 (4) | 20,425 (4) | |

| Trauma center | 41 | 100,947 20) | 4,835 (21) | 96,112 (20)) | 0.0039 |

| Teaching | 22 | 41,377 (8) | 2,004 (9) | 39,373 (8) | 0.0232 |

| Med-Surg Hospital Beds | <.0001 | ||||

| (1) < 100 | 107 | 134,972 (27) | 5,872 (25) | 129,100 (27) | |

| (2) > 100 | 177 | 370,343 (73) | 17,468 (75) | 352,875 (73) | |

|

| |||||

|

Patient Characteristics

| |||||

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 77.6 ± 8.09 | 78.58 ± 8.14 | 77.52 ± 8.08 | <.0001 | |

| 80+ | 208,290 (41) | 10,888 (47) | 197,402 (41) | ||

| 75 < 80 | 97,192 (19) | 4,346 (19) | 92,846 (19) | ||

| 70– < 75 | 95,733 (19) | 4,081 (17) | 91,652 (19) | ||

| 65– < 70 | 104,100 (21) | 4,025 (17) | 100,075 (21) | ||

| Male | 196,279 (39) | 9,604 (41) | 186,675 (39) | <.0001 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | <.0001 | ||||

| White | 329,145 (65) | 15,475 (66) | 313,670 (65) | ||

| Black | 32,265 (6) | 1,565 (7) | 30,700 (6) | ||

| Hispanic | 83,367 (17) | 3,803 (16) | 79,564 (17) | ||

| Asian | 34,262 (7) | 1,520 (7) | 32,742 (7) | ||

| American Indian | 1,388 (0.3) | 73 (0.3) | 1,315 | ||

| Other | 24,888 (5) | 904 (4) | 23,984 (5) | ||

| Day of week of service | 0.0008 | ||||

| Weekday (M–F) | 357,722 (71) | 16,748 (72) | 340,974 (71) | ||

| Weekend (Sat–Sun) | 147,593 (29) | 6,592 (28) | 141,001 (29) | ||

| AMA*/Eloped | 8,425 (2) | 650 (3) | 7,775 (2) | <.0001 | |

| Nursing Home Patient | 14,080 (3) | 1,269 (5) | 12,811 (3) | <.0001 | |

AMA= against medical advice

Table 2.

Discharge Diagnoses of the Study Cohort

| ED Discharge Diagnosis | Total Cohort (n=505,315) | Admitted within 7 days (n=23,340)(%) | % Cases with Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| End stage renal disease | 193 | 22 (11.4) | 0.038 |

| Chronic renal disease | 399 | 42 (10.5) | 0.079 |

| Congestive heart failure | 5,019 | 483 (9.6) | 0.99 |

| Noninfectious lung disease | 1,036 | 97 (9.4) | 0.21 |

| Neoplasm | 1,593 | 142 (8.9) | 0.32 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 11,855 | 893 (7.5) | 2.3 |

| Pneumonia | 5,547 | 417 (7.5) | 1.1 |

| Endocrine; nutritional; immunity and metabolic disease | 9,669 | 691 (7.2) | 1.9 |

| Mental Illness | 10,660 | 751 (7.1) | 2.1 |

| Disease of the blood | 2,569 | 174 (6.8) | 0.51 |

| Symptom: Abdominal pain | 20,737 | 1281 (6.2) | 4.1 |

| Complications and adverse events | 9,386 | 571 (6.1) | 1.9 |

| Other symptoms | 23,085 | 1,400 (6.1) | 4.6 |

| Diabetes | 8,388 | 501 (6.0) | 1.7 |

| Urinary tract infection | 18,306 | 1,075 (6.0) | 3.6 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 4,212 | 246 (5.8) | 0.83 |

| Asthma | 3,772 | 211 (5.6) | 0.75 |

| GI system disease | 33,453 | 1,863 (5.6) | 6.6 |

| Skin and subcutaneous infection | 9,824 | 489 (5.0) | 1.9 |

| Heart disease | 2,045 | 95 (4.7) | 0.4 |

| Other renal and genitourinary disease | 18,852 | 874 (4.6) | 3.7 |

| Other respiratory disease | 20,962 | 955 (4.6) | 4.1 |

| Other infections | 5,249 | 236 (4.5) | 1 |

| Disease of the musculoskeletal system, skin and tissue | 42,444 | 1,857 (4.4) | 8.4 |

| Circulatory disorder | 5,799 | 249 (4.3) | 1.1 |

| Other | 20,167 | 840 (4.2) | 4 |

| Nervous system disorders | 19,211 | 719 (3.7) | 3.8 |

| Dysrhythmias | 10,637 | 390 (3.7) | 2.1 |

| Symptom: Headache | 7,636 | 279 (3.7) | 1.5 |

| Major injuries | 1,470 | 53 (3.6) | 0.29 |

| Minor injuries | 35,360 | 1,272 (3.6) | 7 |

| Symptom: Chest pain | 22,219 | 775 (3.5) | 4.4 |

| Upper respiratory infection | 9,290 | 316 (3.4) | 1.8 |

| Hypertension | 8,844 | 289 (3.3) | 1.8 |

| Other Injuries | 70,380 | 2,123 (3.0) | 14 |

| Symptoms: Dizziness, vertigo and syncope | 25,047 | 669 (2.7) | 5 |

In order of the emergency department diagnoses with the greatest % admission after discharge. The % is the number admitted after discharge divided by the number who present to the ED.

Predictors of 7-Day Hospital Inpatient Admission after Discharge

Table 3 describes the results of the multivariate model. For-profit hospital EDs, as compared to not-for-profit hospital EDs, were found to have an increased likelihood of inpatient admissions within 7 days following the ED visit (AOR 1.14 95% CI 1.03–1.26). Compared to a reference group of patients age 65–70, increasing age (age 70–74 AOR 1.12, 95% CI 1.07–1.17; age 75–79 AOR 1.18, 95% CI 1.13–1.23; age 80+ AOR 1.4, 95% CI 1.35–1.46) was associated with a greater likelihood of admission after discharge. Patients with the greatest odds of an admission after discharge were those that left against medical advice (AMA) or eloped (left prior to discharge) (AOR 1.82, 95% CI 1.67–1.98) and those with a skilled nursing facility residence(AOR 1.82, 95% CI 1.72–1.94). The three most common ED discharge diagnoses associated with admission were end stage renal disease (AOR 3.83, 95% CI 2.42–6.08), chronic renal disease (AOR 3.19, 95% CI 2.26–4.49), and congestive heart failure (CHF) (AOR 3.01, 95% CI 2.59–3.50).

Table 3.

Multivariable Logistic Regression of Hospital Admissions

| Hospital Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership (Ref=Not-For-Profit) | ||

| For-Profit | 1.14 (1.03–1.26) | 0.0125 |

| County | 0.93 (0.78–1.12) | 0.4465 |

| Trauma center | 0.97 (0.86–1.10) | 0.628 |

| Teaching | 1.11 (0.94–1.31) | 0.2213 |

| Med-Surg Hospital Beds (Ref= ≥ 100) | ||

| < 100 | 0.90 (0.82–0.98) | 0.0174 |

|

| ||

|

Patient Characteristics

| ||

| Age (Ref=65–69) | <.0001 | |

| 80+ | 1.40 (1.35–1.46) | <.0001 |

| 75–79 | 1.18 (1.13–1.23) | <.0001 |

| 70–74 | 1.12 (1.07–1.17) | <.0001 |

| Male | 1.11 (1.08–1.14) | <.0001 |

| Race/Ethnicity (Ref=white) | <.0001 | |

| Black | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 0.7177 |

| Hispanic | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) | <.0001 |

| Asian | 0.88 (0.83–0.93) | <.0001 |

| American Indian | 1.11 (0.87–1.41) | 0.4089 |

| Other | 0.78 (0.72–0.84) | <.0001 |

| Day of week of service (Ref= Weekday) | ||

| Weekend (Sat–Sun) | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | 0.0059 |

| AMA*/Eloped | 1.82 (1.67–1.98) | <.0001 |

| Nursing Home Patient | 1.82 (1.72–1.94) | <.0001 |

| Discharge Diagnoses (Ref= Hypertension) | ||

| End stage renal disease | 3.83 (2.42–6.08) | <.0001 |

| Chronic renal disease | 3.19 (2.26–4.49) | <.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 3.01 (2.59–3.50) | <.0001 |

| Neoplasms | 2.95 (2.39–3.64) | <.0001 |

| Noninfectious lung disease | 2.95 (2.32–3.75) | <.0001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2.35 (2.05–2.69) | <.0001 |

| Pneumonia | 2.27 (1.95–2.65) | <.0001 |

| Endocrine; nutritional; metabolic and immunity disorders | 2.17 (1.89–2.50) | <.0001 |

| Mental illness | 2.17 (1.89–2.49) | <.0001 |

| Diseases of the blood | 1.97 (1.62–2.40) | <.0001 |

| Symptom: Abdominal pain | 1.97 (1.73–2.24) | <.0001 |

| Other symptoms | 1.85 (1.63–2.11) | <.0001 |

| Asthma | 1.81 (1.51–2.17) | <.0001 |

| Diabetes | 1.81 (1.56–2.09) | <.0001 |

| Complications and adverse events | 1.78 (1.54–2.05) | <.0001 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1.77 (1.55–2.02) | <.0001 |

| Gastrointestinal system disease | 1.71 (1.50–1.93) | <.0001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.69 (1.42–2.01) | <.0001 |

| Skin and subcutaneous infection | 1.55 (1.34–1.80) | <.0001 |

| Other infections | 1.42 (1.19–1.69) | <.0001 |

| Other renal and genitourinary disease | 1.38 (1.20–1.58) | <.0001 |

| Other Respiratory Disease | 1.36 (1.19–1.55) | <.0001 |

| Disease of the musculoskeletal system, skin and tissue | 1.35 (1.19–1.53) | <.0001 |

| Heart disease | 1.32 (1.04–1.67) | 0.023 |

| Circulatory disorder | 1.27 (1.07–1.51) | 0.007 |

| Other | 1.19 (1.04–1.36) | 0.013 |

| Symptoms: Headache | 1.15 (0.98–1.36) | 0.094 |

| Dysrhythmias | 1.13 (0.97–1.32) | 0.12 |

| Nervous system disorder | 1.13 (0.98–1.30) | 0.089 |

| Minor injuries | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | 0.149 |

| Major injuries | 1.07 (0.80–1.45) | 0.644 |

| Upper respiratory infection | 1.07 (0.91–1.26) | 0.405 |

| Symptom: Chest pain | 1.05 (0.91–1.20) | 0.51 |

| Other injuries | 0.87 (0.77–0.99) | 0.032 |

| Symptom: Dizziness, vertigo and syncope | 0.79 (0.69–0.91) | 0.001 |

AMA= against medical advice

DISCUSSION

Using the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) files for 2007, the study team examined the relationship between certain patient and hospital characteristics and hospital inpatient admissions following ED discharge from California hospitals in Medicare patient visits age 65 and older. Increasing age, male gender, leaving the ED against medical advice or eloping prior to discharge, and nursing home residence were found to have a greater odds of a 7-day admission after ED discharge. The ED discharge diagnoses with the greatest odds of an admission were as a result of a chronic medical condition. Compared to non-Latino whites, the older cohort showed Hispanic and Asian subjects to have a lower likelihood of admission after discharge.

To our knowledge, this study is the first large scale evaluation of short-term hospital inpatient admissions after ED discharge in Medicare patients. Previous studies evaluating health service use following ED discharge focus on ED revisits10–16 which may not indicate a related condition, have small sample sizes or occur at single institutions.12,13,15,17–23; are conducted in countries with different health system characteristics than the U.S12–16,20,22,24–28, or assess follow-up periods of 30 to 90 days15,17,19,21,22,26,29,30, which are more likely to include events unrelated to the initial ED visit.

Close to 1 of 25 or 4.6%of Medicare patients seen in EDs daily require an admission within 7 days of discharge. This rate is high possibly due to factors not identified through administrative analysis such as frailty,30 functional capacity, and support situations.20 The clinical variables available in this data set included the primary and other diagnosis as well as the principal and other diagnoses. This study evaluated the primary ED diagnosis. Previous studies have suggested that older patients with poor physical functioning that have difficulty completing their activities of daily living (ADLs) or depend on support services, such as a nurse or caretaker, often recover poorly following an ED visit.17,21,22,31.

Patients at highest risk for an admission after discharge were found to be patients who left the ED AMA or elope(leave without permission prlor to discharge). Similar to prior studies, these findings confirm that patients leaving AMA are not less ill as compared to other patients who wait to be evaluated in the ED.32–35 Patients of skilled nursing facilities were also at increased risk suggesting that these patients may have more complex disease presentations when arriving in the ED. These findings suggest that providers managing ED patients from skilled nursing facilities consider obtaining histories from a number of contacts to the patient, including the skilled nursing facility staff and family. Providers evaluating patients who desire to leave prior to a complete evaluation should consider providing thorough discharge instructions regardless of their desire to leave and ensure that the patient has appropriate follow-up in a timely manner.

The study identified the discharge diagnoses associated with admission after discharge and found that the diagnoses with the greatest odds of an admission after discharge indicated chronic conditions (ESRD, CRD, and CHF). Although these diagnoses often require regular health care provider encounters, our findings suggest that when presenting to the ED, patients with these diagnoses may harbor disease processes not immediately apparent to the provider. Regardless of age, providers evaluating patients with these conditions in the ED, upon discharge should consider securing short-term follow-up, such as within 24 to 48 hours, with their primary care provider so as to prevent an inpatient admission.

This study also found that non-Latino whites were at greater risk of experiencing admissions after discharge when compared with other races. This may be due to differences in social or family support provided by different cultures that could prevent the need for an admission following an ED visit. It could also be due to different cultures having varied thresholds for visiting the ED.

This study has limitations. First, the analysis is based on data derived from ICD-9 codes which is limited in that it is retrospective and could reflect coding that is incomplete. Second, OSHPD does not provide information about federal hospitals, and our findings are not generalizable to these facilities. Third, although California represents 12% of the US population36 and this study provides important information for policy makers and hospital administrators, the findings cannot be generalized to the entire US population. Fourth, although the study team did case-mix adjust using discharge diagnosis codes, the OSHPD ED files lack data of pre-existing comorbidities. Also, the analysis did not include information on previous hospital or emergency department visits as that would require the use of data from a prior year. In addition, although large, the files and the design of the study do not provide explanations of causation between the patient and hospital characteristics and outcomes. Also, the files lack clinical variables that evaluate functional impairment, social support, transitions in care, prior utilization, and health literacy. Finally, the data is several years old as a result of the time it took to acquire (2 years), link and clean the files (2 years). Despite these limitations, this study is an important first step in identifying factors that may predict the need for subsequent admission shortly following the ED visit.

Short-term hospital admission following discharge from the ED may be an indicator of incomplete ED or follow-up care. This study identified important patient and hospital characteristics associated with admissions within 7 days of ED discharge in an older age > 65 years cohort with Medicare insurance. Patients who left the ED AMA, residents of skilled nursing facilities, and patients with chronic diseases were especially at risk. These findings suggest that quality improvement efforts focus on these high-risk individuals by ensuring immediate outpatient follow-up.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study team would like to thank Jerome Hoffman, MD, MA for reviewing this manuscript and his insightful comments.

Funding and Support: This research was supported by the Emergency Medicine Foundation (Sun), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Sun R03 HS18098), and the UCLA Older American Independence Center NIH/NIA pilot grant. Dr. Gabayan receives support from the NIH/NCRR/NCATS UCLA CTSI (Grant KL2TR000122). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the NIA. The funding organizations did not have a role in the design and conduct of the study; management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Funding and Support: This research was supported by the Emergency Medicine Foundation (Sun), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Sun R03 HS18098), and the UCLA Older American Independence Center NIH/NIA pilot grant. Dr. Gabayan receives support from the NIH/NCRR/NCATS UCLA CTSI (Grant KL2TR000122). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the NIA. The funding organizations did not have a role in the design and conduct of the study; management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Gelareh Z. Gabayan, Benjamin C. Sun and Catherine A. Sarkisian conceived the study. Gelareh Z. Gabayan and Benjamin C. Sun obtained funding. Gelareh Z. Gabayan and Benjamin C. Sun designed the study. Li-Jung Liang conducted the statistical analyses and proved statistical guidance. Gelareh Z. Gabayan drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. Gelareh Z. Gabayan takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest in association with this study.

References

- 1.Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:370–376. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients: Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. 1991. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:145–151. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2002.003822. discussion 151–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Accessed April 9, 2012];OSHPD Website. Available at: http://www.oshpd.ca.gov/

- 4.Gabayan GZ, Derose SF, Asch SM, et al. Patterns and predictors of short-term death after emergency department discharge. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:551–558. e552. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sklar DP, Crandall CS, Loeliger E, et al. Unanticipated death after discharge home from the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:735–745. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunnarsdottir OS, Rafnsson V. Death within 8 days after discharge to home from the emergency department. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18:522–526. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckn045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kefer MP, Hargarten SW, Jentzen J. Death after discharge from the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24:1102–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guttmann A, Schull MJ, Vermeulen MJ, et al. Association between waiting times and short term mortality and hospital admission after departure from emergency department: population based cohort study from Ontario, Canada. BMJ. 2011;342:d2983. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. [Accessed August 25, 2010];AHRQ Clinical Classification Software. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

- 10.Pham JC, Kirsch TD, Hill PM, DeRuggerio K, Hoffmann B. Seventy-two-hour returns may not be a good indicator of safety in the emergency department: A national study. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:390–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keith KD, Bocka JJ, Kobernick MS, et al. Emergency department revisits. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:964–968. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu CL, Wang FT, Chiang YC, et al. Unplanned emergency department revisits within 72 hours to a secondary teaching referral hospital in Taiwan. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:512–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu SC. Analysis of patient revisits to the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:366–370. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(92)90022-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bentley J, Meyer J. Repeat attendance by older people at accident and emergency departments. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48:149–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCusker J, Healey E, Bellavance F, et al. Predictors of repeat emergency department visits by elders. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:581–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCusker J, Ionescu-Ittu R, Ciampi A, et al. Hospital characteristics and emergency department care of older patients are associated with return visits. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:426–433. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caplan GA, Brown A, Croker WD, et al. Risk of admission within 4 weeks of discharge of elderly patients from the emergency department--the DEED study. Discharge of elderly from emergency department. Age Ageing. 1998;27:697–702. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.6.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon JA, An LC, Hayward RA, et al. Initial emergency department diagnosis and return visits: risk versus perception. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32:569–573. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hastings SN, Schmader KE, Sloane RJ, et al. Adverse health outcomes after discharge from the emergency department--incidence and risk factors in a veteran population. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1527–1531. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0343-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowland K, Maitra AK, Richardson DA, et al. The discharge of elderly patients from an accident and emergency department: Functional changes and risk of readmission. Age Ageing. 1990;19:415–418. doi: 10.1093/ageing/19.6.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedmann PD, Jin L, Karrison TG, et al. Early revisit, hospitalization, or death among older persons discharged from the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:125–129. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2001.21321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson DB. Elderly patients in the emergency department: A prospective study of characteristics and outcome. Med J Aust. 1992;157:234–239. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1992.tb137125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denman SJ, Ettinger WH, Zarkin BA, et al. Short-term outcomes of elderly patients discharged from an emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:937–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb07278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuan WS, Mahadevan M. Emergency unscheduled returns: Can we do better? Singapore Med J. 2009;50:1068–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nunez S, Hexdall A, Aguirre-Jaime A. Unscheduled returns to the emergency department: An outcome of medical errors? Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:102–108. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.016618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCusker J, Roberge D, Vadeboncoeur A, et al. Safety of discharge of seniors from the emergency department to the community. Healthc Q. 2009;12(Spec No Patient):24–32. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.20963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, et al. Prediction of hospital utilization among elderly patients during the 6 months after an emergency department visit. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:438–445. doi: 10.1067/mem.2000.110822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan JS, Kao WF, Yen DH, et al. Risk factors and prognostic predictors of unexpected intensive care unit admission within 3 days after ED discharge. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:1009–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hastings SN, Oddone EZ, Fillenbaum G, et al. Frequency and predictors of adverse health outcomes in older Medicare beneficiaries discharged from the emergency department. Med Care. 2008;46:771–777. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181791a2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hastings SN, Purser JL, Johnson KS, et al. Frailty predicts some but not all adverse outcomes in older adults discharged from the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1651–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01840.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chin MH, Jin L, Karrison TG, et al. Older patients' health-related quality of life around an episode of emergency illness. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:595–603. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding R, Jung JJ, Kirsch TD, et al. Uncompleted emergency department care: Patients who leave against medical advice. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:870–876. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pennycook AG, McNaughton G, Hogg F. Irregular discharge against medical advice from the accident and emergency department--a cause for concern. Arch Emerg Med. 1992;9:230–238. doi: 10.1136/emj.9.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker DW, Stevens CD, Brook RH. Patients who leave a public hospital emergency department without being seen by a physician. Causes and consequences. JAMA. 1991;266:1085–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Keane D, et al. Consequences of queuing for care at a public hospital emergency department. JAMA. 1991;266:1091–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed Jan 2012]; http://www.statehealthfacts.org.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.