Abstract

Background

Many women engage in intravaginal practices (IVP) with a goal of improving genital hygiene and increasing sexual pleasure. IVP can disrupt the genital mucosa, and some studies have found that IVP increases risk of acquisition of HIV and bacterial vaginosis (BV). Limited prior research also suggests significant associations between IVP, herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), and high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV).

Methods

We examined associations between IVP and HPV, BV, and HSV-2 among 200 women in rural Malawi participating in a clinic-based study on sexual and reproductive tract infections. We calculated prevalence ratios for the associations between frequency and type of IVP and outcomes of HPV, BV, and HSV-2.

Results

Intravaginal practices were commonly performed, with 95% of women reporting current use of at least one practice. Infections were also frequently detected: 22% of the sample had at least one high risk HPV type, 51% had BV, and 50% were HSV-2 seropositive. We observed no significant associations between type of IVP, frequency of IVP, or a combined measure capturing type and frequency of IVP – and any of the infection outcomes.

Conclusions

While both IVP and our outcomes of interest (BV, HPV, and HSV-2) were common in the study population, we did not detect associations between IVP type or frequency and any of the three infections. However, the high prevalence and frequency of IVP may have limited our ability to detect significant associations.

Keywords: intravaginal practices, Herpes Simplex virus Type 2, Vaginosis, Bacterial, Human Papilloma Virus, reproductive tract infection

Introduction

Intravaginal practices (IVP) encompass a wide range of practices that women may undertake for a variety of purposes including maintaining genital health, personal hygiene, and enhancing sexual experience.(1–4) Some women who perform IVP use multiple substances simultaneously while others use only one product or practice. The frequency of IVP may vary by type and purpose of the practice.(3) Some women use certain practices, like vaginal douching, only once a month.(2) The same women may use other practices, like inserting cloth, multiple times daily. Types of IVP vary across and within countries. For example, women more commonly report cleansing with commercial products in Thailand and cleansing with household products like soap or aspirin in South Africa.(1) In Malawi, IVP are common, with 95% of women reporting at least one practice in the previous 30 days.(5) In Zimbabwe and Malawi, women used a wide range of substances and application methods depending on the purpose of the IVP. Women inserted or ingested herbal or other natural substances to dry and tighten the vagina; they inserted cloth or exposed the vagina to air or heat to remove vaginal secretions; they finger-cleansed using water or detergent-like products for cleaning; they used cooking oil or Vaseline intravaginally to lubricate; they swallowed or inserted tablets such as aspirin to reduce pain; and they consumed or inserted sugary products to dry the vagina and make it “sweet.”(4) The type of substance varies by country and within countries by region or ethnic group.

IVP are also associated with unintended and harmful side effects. IVP can disrupt genital mucosa, alter vaginal flora, and increase women’s risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.(6,7)

A limited literature suggests IVP may be associated with increased prevalence of high- risk human papillomavirus (hr-HPV) and it is possible that these practices could also affect progression to cervical cancer.(2,8–10) IVP may also be associated with an increased risk of bacterial vaginosis (BV)(11–13), a pathologic alteration of vaginal flora, and herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) infection (14), though the literature on these associations has been inconsistent.(15). In addition to the considerable morbidities caused by these infections for individual women, such as reduced quality of life and recurrent outbreaks (16,17),both BV and HSV-2 are linked to an increased risk of HIV acquisition and transmission.(7,18) More data are needed to clarify associations between IVP, and the outcomes of prevalent hr-HPV, BV, and HSV-2, while accounting for variation in IVP type and frequency.

Our objective was to assess the associations between type and frequency of IVP, and detection of hr-HPV, BV, and HSV-2 in a sample of care-seeking women in rural Lilongwe District, Malawi.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

We enrolled women in a cross-sectional, clinic-based study of sexual and reproductive tract infections conducted from January to August 2015. The study was based out of a rural clinic in Lilongwe District, Malawi. Women between 18 and 49 years of age, seeking care for genitourinary symptoms broadly defined as abnormal menstrual cycle or patterns of bleeding; pain with urination, pain during sex, abdominal pain, lower back pain, or any type of pelvic pain; incontinence or unusual urine odor, frequency or color; unusual vaginal discharge in terms of quantity, odor, color or consistency were eligible to participate. Women who were pregnant or menstruating at the time of the clinic visit were ineligible to participate.

Data collection

All women received a pelvic exam with collection of a vaginal sample to assess for BV (Nugent score), and a cervical sample to test for hr-HPV (GeneXpert HPV assay, Sunnyvale, CA). HSV-2 serostatus was assessed from serum (HerpeSelect, Cypress, California). We also tested cervical samples for gonorrhea and chlamydia (ProbeTec, BD Diagnostics, Sparks, MD) and serum samples for HIV (Uni-Gold, Trinity Biotech, Jamestown, NY) and syphilis, but did not include these in our analysis because of low prevalence. Following the exam, a trained research assistant conducted a brief questionnaire via tablet computer to assess the timing of IVP (before sex, after sex, both times, neither), type of IVP, frequency of IVP, and other sexual and reproductive health factors. Survey data were recorded electronically using the Magpi data collection system (Magpi, Washington, DC).

Measures

Outcomes

Cervical samples were tested for hr-HPV using the GeneXpert HPV assay. The GeneXpert provides the following results: (a) negative for hr-HPV; (b) positive for hr-HPV type 16, (c) positive for hr-HPV types 18/45; or (d) positive for 11 other pooled hr-HPV types (31, 33, 35, 39, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68). For this analysis, because of our limited sample size, we combined all types of hr-HPV into a binary variable (positive/negative). We used Nugent scoring to assess for BV. We categorized a score of 7–10 as positive for BV. Any women who tested seropositive for HSV-2 was classified as having HSV-2.

Exposures

We asked participants which IVP they used: cleansing with soap and water; cleansing with cotton, cloth or tissue; inserting alum or other powder, herbs, leaves, castor oil, or any other vaginal products from a traditional healer or herbalist. We also asked how frequently they engaged in each practice: more than once a day, once a day, a few times per week, a few times per month, once a month or less often, never. For the primary analysis we categorized frequency into three groups: more than once per day, once per day or less often, and never. When examining overall IVP frequency, if women reported multiple types of IVP they were categorized according to their most frequent practice.

Analysis

All analysis was done using Stata 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and SAS 9.3 (SAS, Cary, NC).

Type of IVP

As greater than 10% of the study population was outcome-positive for our primary outcomes (hr-HPV, BV, HSV-2), we calculated prevalence ratios (PRs) rather than odds ratios.(19) We used a generalized linear model with a binomial distribution and log link to examine the association between type of practice (cleansing with soap and water, cleansing with cotton, cloth or tissue, and inserting any other products) and prevalent hr-HPV, BV, and HSV-2. We only assessed unadjusted associations, as adjustment for other variables led to imprecise estimates due to small cell sizes.

Frequency of IVP

To assess the association between frequency of IVP and infections we ran three separate unadjusted models, one for each IVP type (cleansing with soap and water, cleansing with cotton, cloth, or tissue, and any IVP). Due to the small number of participants who reported using any substance other than soap, cotton, cloth and tissue, we were not able to consider this other group in a separate regression analysis. We created a directed acyclic graph (20) based on existing literature to identify potential confounders of the association between IVP and our three outcomes. We retained variables as confounders in the fully-adjusted multivariable model based on a change-in-estimate criterion: if removal of the variable led to a change of greater than 20% in the association between the main independent variable and the outcome, it was retained in the model. We tested for age, education, household income, lifetime number of sexual partners, age at first sex, and STI diagnosis. Within each outcome, any variable found to confound the association of interest in any model was also retained in the other multivariable models, to ease interpretability of adjusted estimates.

Type and frequency of IVP

In order to examine the joint effects of IVP type and IVP frequency, we created a new categorical variable of “IVP-profile” by combining these measures. A woman was classified into one of five categories: 1) high frequency (>1/day) for both cleansing with soap and water and with cotton, cloth or tissue; 2) high frequency for cleansing with soap and water and low frequency (≤1/day) for cleansing with cotton, cloth, or tissue; 3) low frequency for soap and water and high frequency for cotton, cloth or tissue; 4) low frequency for both practices; 5) reports neither. As we had small cell sizes for some IVP categories, we limited this analysis to unadjusted models only.

Ethical approval

This project received ethical approval from the Ohio State University Institutional Review Board and the University of Malawi College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee.

Results

Participant characteristics

We screened a total of 234 women and enrolled 200 women in the study. We included 199 women in this analysis for HPV, all 200 women for BV, and 197 women for HSV-2. The median age of women in our population was 33 years (interquartile range (IQR): 29,38) and 34% of women had at least some secondary education (Table 1). Nearly all were married (92%), and women reported a median of 2 lifetime sexual partners (IQR: 1, 3).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics of 193 care-seeking women in rural Malawi

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (med, IQR) | 33 | (29, 38) |

| Married | 183 | (92) |

| Education | ||

| < 2 years | 21 | (10) |

| 2–4 years | 30 | (15) |

| 5–8 years | 82 | (41) |

| Some secondary schooling | 67 | (34) |

| Number of lifetime sexual partners (med, IQR) | 2 | (1, 3) |

| Age at first sex (med, IQR) | 18 | (16, 19) |

| HPVa, b | ||

| hr-HPV positive | 43 | (22) |

| HPV 16-positive | 8 | (4) |

| HPV 18/45-positive | 10 | (5) |

| Other hr-HPV-positive | 30 | (15) |

| Bacterial vaginosis | 101 | (51) |

| Abnormal cervical lesions | 16 | (9) |

| HIV-seropositive | 6 | (3) |

| HSV-2-seropositive | 99 | (50) |

| Gonorrhea | 9 | (5) |

| Chlamydia | 0 | (0) |

Results from GeneXpert HPV assay

Some women had multiple types of hr-HPV

med= median; IQR=interquartile range; HPV=human papillomavirus; HIV=human immunodeficiency virus; HSV=herpes simplex virus

Three percent of women (n=6) were living with HIV, and 5% of all participants tested positive for gonorrhea at the time of their visit. Twenty-two percent (n=43) of participants tested positive for hr-HPV infection, some of whom were infected with more than one hr-HPV type (Table 1). Half (50%) were HSV-2 seropositive, and 51% had BV.

Most (96%) women used IVP (Table 2). Cleansing with cotton, cloth, or tissue was most commonly reported (94%) followed by cleansing with soap and water (47%). Very few women (5%) reported using substances other than soap, cotton, cloth, or tissue. Among women reporting any IVP, these practices were frequent: 61% of women who cleansed with soap and water did so more than once per day, and 67% of women who cleansed with cotton, cloth or tissue did so more than once per day.

Table 2.

Frequency of IVP, by practice

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| No IVP | 8 | (4) |

| Cleansing with water | 188 | (95) |

|

| ||

| Cleansing with soap and water

| ||

| Frequency | ||

| More than once per day | 57 | (29) |

| Once per day | 29 | (15) |

| A few times per week | 4 | (2) |

| A few times per month | 3 | (1) |

| Once a month or less often | 1 | (<1) |

| Never | 104 | (52) |

|

| ||

| Cleansing with cotton, cloth or tissue

| ||

| Frequency | ||

| More than once per day | 125 | (63) |

| Once per day | 49 | (25) |

| A few times per week | 10 | (5) |

| A few times per month | 2 | (1) |

| Once a month or less often | 0 | (0) |

| Never | 12 | (6) |

|

| ||

| Inserting other products

| ||

| Frequency | ||

| More than once per day | 1 | (<1) |

| Once per day | 3 | (1) |

| A few times per week | 1 | (<1) |

| A few times per month | 1 | (<1) |

| Once a month or less often | 5 | (2) |

| Never | 188 | (95) |

IVP=intravaginal practices

Timing is only among those who reported doing that practice

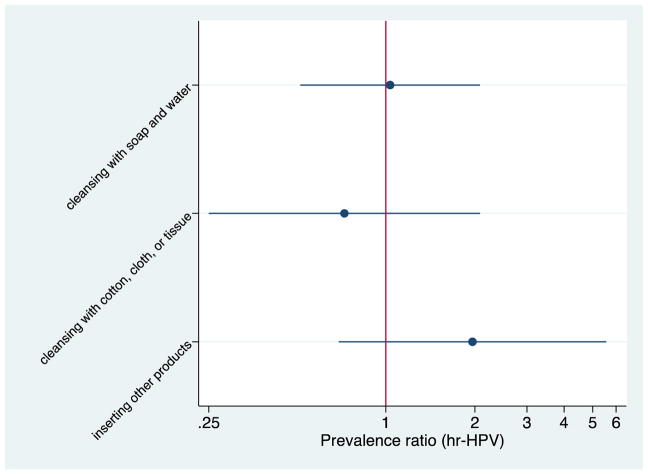

Associations between IVP and hr-HPV

We found no statistically significant association between IVP type and hr-HPV (cleansing with soap and water PR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.51, 2.08; cleansing with cotton, cloth or tissue PR 0.73, 95% CI: 0.25, 2.08; other products PR: 1.96, 95% CI: 0.69, 5.5; Figure 1). We also found no association between IVP frequency and hr-HPV in unadjusted or adjusted models focusing on any IVP (adjusted PR for ≤1/day: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.45, 1.68; PR for never: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.13, 5.28) or separately for cleansing with soap and water, or cleansing with cotton, cloth or tissue (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted prevalence ratios comparing different types of IVP and hr-HPV1

1Prevalence ratios > 1.0 indicates increased risk of hr-HPV with a particular type of IVP vs. not using that type

Examining IVP type and frequency combined, we did not observe any significant associations between the IVP-profile variable and hr-HPV (low frequency PR 0.65, 95% CI: 0.32, 1.33; Table 4).

Table 4.

Unadjusted associations between IVP profile and hr-HPV, BV, and HSV-2

| hr-HPV | BV | HSV-2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| PR | (95% CI) | PR | (95% CI) | PR | (95% CI) | |

| Higha frequency soap/High frequency cotton, cloth, tissue | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| High frequency soap/ Lowb frequency cotton, cloth, tissue | 0.54 | (0.18, 1.66) | 0.92 | (0.55, 1.55) | 0.88 | (0.53,1.48) |

| Low frequency soap/ High frequency cotton, cloth tissue | 0.51 | (0.26, 0.98) | 0.96 | (0.69, 1.33) | 0.75 | (0.53, 0.94) |

| Low frequency soap/ Low frequency cotton, cloth or tissue | 0.65 | (0.32, 1.33) | 0.67 | (0.42, 1.04) | 0.89 | (0.61, 1.28) |

| None | 0.68 | (0.19, 2.51) | 0.58 | (0.22, 1.52) | 0.55 | (0.21, 1.45) |

hr-HPV= high-risk human papillomavirus; BV= bacterial vaginosis; HSV2= herpes simplex virus type 2

High frequency is defined as > 1/day

Low frequency is defined as ≤ 1/day

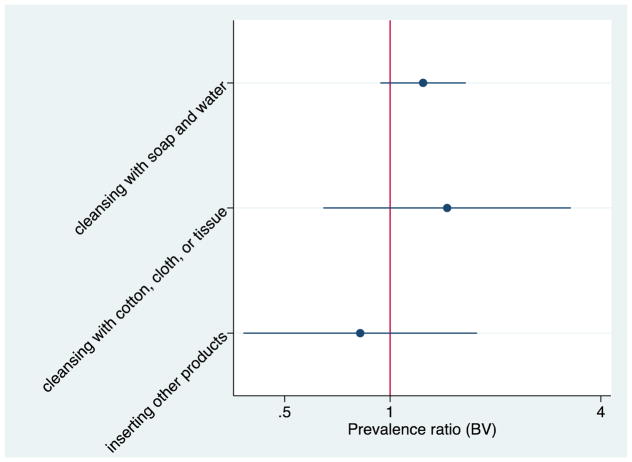

Associations between IVP and BV

We found no statistically significant association between IVP type and BV (cleansing with soap and water PR: 1.22, 95% CI: 0.93, 1.62; cleansing with cotton, cloth or tissue PR 1.47, 95% CI: 0.65, 3.30; other products PR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.38, 1.76; Figure 2). We found no association between IVP frequency and BV in unadjusted or adjusted models focusing on any IVP (PR for ≤1/day: 0.70, 95% CI:0.46, 1.04; PR for never: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.35, 1.91) or separately for cleansing with soap and water, or cleansing with cotton, cloth or tissue (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Unadjusted prevalence ratios comparing different types of IVP and BV1

1Prevalence ratios > 1.0 indicates increased risk of BV with a particular type of IVP vs. not using that type

Table 3.

Associations between frequency of IVP, hr-HPV, BV, and HSV-2

| hr-HPV | BV | HSV-2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | Unadjusted | Adjustedc | |||||||

| PR | (95% CI) | PR | (95% CI) | PR | (95% CI) | PR | (95% CI) | PR | (95% CI) | PR | (95% CI) | |

| Any IVP | ||||||||||||

| > 1/day | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| ≤ 1/day | 0.98 | (0.52, 1.85) | 0.87 | (0.45, 1.68) | 0.69 | (0.47, 1.03) | 0.70 | (0.46, 1.04) | 1.06 | (0.78, 1.46) | 1.01 | (0.75, 1.37) |

| Never | 0.58 | (0.09, 3.70) | 0.84 | (0.13, 5.28) | 0.68 | (0.27, 1.68) | 0.82 | (0.35, 1.91) | 0.75 | (0.30, 1.86) | 0.82 | (0.36, 1.84) |

| Soap and water | ||||||||||||

| > 1/day | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| ≤ 1/day | 0.48 | (0.19, 1.20) | 0.51 | (0.20, 1.26) | 1.01 | (0.70, 1.45) | 1.06 | (0.73, 1.54) | 0.75 | (0.49, 1.15) | 0.74 | (0.48, 1.13) |

| Never | 0.72 | (0.40, 1.27) | 0.80 | (0.44, 1.45) | 0.81 | (0.60, 1.10) | 0.86 | (0.62, 1.19) | 0.84 | (0.62, 1.13) | 0.85 | (0.63, 1.160 |

| Cotton, cloth or tissue | ||||||||||||

| > 1/day | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| ≤ 1/day | 0.91 | (0.50, 1.67) | 0.86 | (0.46, 1.61) | 0.76 | (0.55, 1.06) | 0.81 | (0.58, 1.14) | 1.05 | (0.78, 1.41) | 1.01 | (0.77, 1.34) |

| Never | 1.16 | (0.41, 3.23) | 1.54 | (0.56, 4.26) | 0.60 | (0.26, 1.34) | 0.66 | (0.30, 1.46) | 0.83 | (0.42, 1.67) | 0.91 | (0.48, 1.72) |

hr-HPV= high-risk human papillomavirus; BV= bacterial vaginosis; HSV2= herpes simplex virus type 2

adjusted for lifetime number of sexual partners and age at first sex

adjusted for age at first sex

adjusted for age at first sex, lifetime number of sexual partners, and age

There also were not any significant associations with IVP-profile and BV (low frequency PR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.42, 1.04; Table 4). However, similar to the hr-HPV model, all estimates were below 1 when compared to high frequency for both types of IVP.

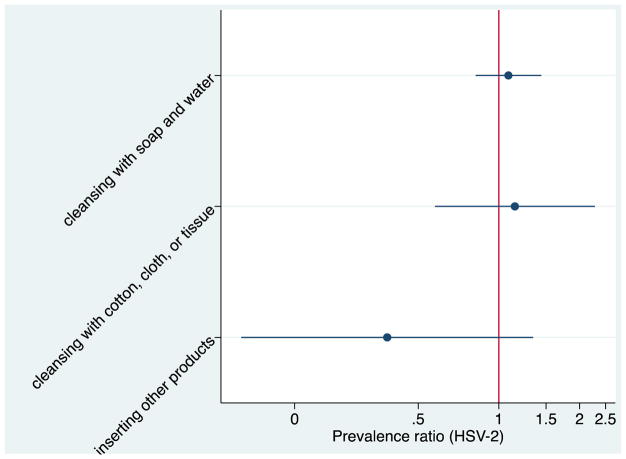

Associations between IVP and HSV-2

Finally, we found no statistically significant association between IVP type and HSV-2 (cleansing with soap and water PR: 1.08, 95% CI: 0.82, 1.44; cleansing with cotton, cloth or tissue PR 1.15, 95% CI:0.58, 2.28; other products PR: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.11, 1.34; Figure 3). When examining the association between IVP frequency and HSV-2 we did not find any significant associations in the unadjusted or adjusted models for any IVP (PR for ≤1/day: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.48, 1.13; PR for never: 0.85, 95% CI:0.63, 1.16) or separately for cleansing with soap and water, or cleansing with cotton, cloth or tissue (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Unadjusted prevalence ratios comparing different types of IVP and HSV-21

1Prevalence ratios > 1.0 indicates increased risk of HSV-2 with a particular type of IVP vs. not using that type

In the model assessing IVP-profile we found that low frequency of soap and high frequency of cotton, cloth, or tissue was associated with a reduced prevalence of HSV-2 (PR: 0.75; 95% CI: 0.53, 0.94). Similar to the hr-HPV and BV outcomes, all other IVP-profiles were non-significant but below 1.

Discussion

While some research suggests that IVP are associated with bacterial vaginosis and potentially other STI transmission, including HPV and HSV-2, we found no significant associations between IVP and the three infections. In an analysis using an IVP-profile capturing all types and varying frequencies of IVP, we observed a non-significant trend of decreasing odds of infection as frequency of IVP decreased. However, when practices were examined separately we did not see the same pattern.

Our study also provides important information on the prevalence of hr-HPV, BV, and HSV-2 in this rural Malawian population. Limited data exist on the prevalence of hr-HPV among Malawian women, and there are no nationwide data on HPV prevalence.(21,22) Similar to our findings, one study found an HPV prevalence (including both low and high risk HPV) of 23% among women without HIV, but found among women with HIV the HPV prevalence was 58%.(23) Another study among women living with HIV also found a higher prevalence of hr-HPV at 38%.(22) We also found BV prevalence in our population in line with findings from other research in Malawi (45% and 52% in two different sites in Malawi).(24) A study among young women in Malawi found a lower HSV-2 prevalence of only 26%. However, the study included younger women ages 15–30, and when restricting to women 25–30 years the prevalence was closer to the 50% , similar to levels found in our study population.(25)

Our null findings on the association between type of IVP and infection prevalence are similar to previous studies on this topic. A cross-sectional study of female sex workers in Burkina Faso found no significant association between douching and HPV (including both low-risk and high-risk types).(26) In a study of women in the United States, there was no significant association identified when examining different douching preparations (chemical, commercial, water/vinegar, water/soda, water only) and cervical carcinoma.(8)

However, our finding that the frequency of IVP was not associated with prevalent infection differs from existing literature. Other studies have found associations between high frequency of IVP and HPV, BV, and HSV-2. The significance and the strength of the associations vary depending on the definition of high frequency, low-frequency, and unexposed.(2,8–10) A meta-analysis found a weak overall association between douching and abnormal cytology; among women who douched more frequently (at least once a week), the pooled adjusted relative risk was 1.86 (95% CI: 1.29, 2.68).(10) However, similar to our findings, the authors observed no significant association between those who douched less frequently and those who never douched.(8) Another study found that daily IVP was associated with BV (OR 4.58; 95% CI 1.26, 16.64) compared to the comparison group of weekly, monthly, or never users.(11) Among high-risk Tanzanian women, douching more than three times per day compared to never douching was significantly associated with HSV-2 positivity, while only douching two times per day was not associated with an increased odds of HSV-2.(14) As the majority of women in our study reported a high frequency of IVP, we may not have had a sufficient number of women reporting a low frequency of IVP to detect significant differences.

Our null findings may also be due in part to differences in substances used for IVP in our population compared to women in previous studies. One of the challenges in assessing the risks associated with IVP is in measurement of IVP, as IVP are culturally specific and the type and frequency of IVP can vary by region. In the studies identifying significant associations, women used commercial preparations or lemon or lime juice, which may be more abrasive than soap and water or cotton, cloth, or tissue that were reported by women included in our study. (9–11,26–28) We did not have enough women reporting inserting other substances to examine the associations using a potentially more caustic substance.

One innovation in our study was the creation of IVP-profiles to incorporate both type and frequency of IVP to obtain a better estimate of the associations of IVP with hr-HPV, BV, and HSV-2. While we did not find any statistically significant associations, all estimates showed reduced prevalence of all three outcomes when comparing women with low frequency of IVP for at least one practice to women reporting high frequency of both practices.

We provide new findings about type of IVP and frequency of IVP, as practiced by care-seeking women in rural Malawi. Our study is one of the first to examine the association between IVP and hr-HPV and HSV-2 and extends previous research by examining the effect of both the type and frequency of IVP. However, our null findings should be interpreted in light of study limitations. As a pilot study, our sample size included 200 women, which limited our power to assess key associations of interest. Nearly half of women reported multiple IVP, and we were unable to separate the effects of different practices, as we did not have a sufficient number of women who reported no practices or only one practice. Additionally, due to the high frequency of IVP, we collapsed the different frequencies of IVP into three categories, which may have introduced differential misclassification bias. As we included women who reported IVP about once a day in the lower frequency category we may have underestimated the true IVP-infection association as their risk of infection may be more similar to those who perform IVP more than once per day. Finally, our sample was comprised of women presenting to a medical clinic with genitourinary symptoms, and as IVP are sometimes undertaken to treat symptomatic infections, it is possible that the high prevalence of IVP may not be generalizable to the rest of the population. However, previous research has found similarly high prevalence of IVP amongst non-clinic populations in east Africa.(3,29,30)

In this study, care-seeking, rural Malawian women frequently engaged in a range of IVP. Our findings on the prevalence of hr-HPV, BV, and HSV-2 were in line with other research in similar settings. We did not find significant associations between IVP and prevalence of our three outcomes of hr-HPV, BV, and HSV-2, suggesting that the intravaginal practices commonly used by women in this region may not be a risk factor for these infections. Future research should examine a larger population and assess the impact of potentially more harmful IVP to gain a better understanding of these associations.

Summary.

Among care-seeking women in rural Malawi, intravaginal practices were not associated with increased prevalent high-risk human papillomavirus, bacterial vaginosis, or herpes simplex virus type 2.

Acknowledgments

Funding support: Center for Clinical and Translational Science, Institute for Population Research

Footnotes

No authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Martin Hilber A, Hull TH, Preston-Whyte E, Bagnol B, Smit J, Wacharasin C, et al. A cross cultural study of vaginal practices and sexuality: implications for sexual health. Soc Sci Med. 2010 Feb;70(3):392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martino JL, Vermund SH. Vaginal Douching: Evidence for Risks or Benefits to Women’s Health. Epidemiol Rev. 2002 Dec 1;24(2):109–24. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxf004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hull T, Hilber AM, Chersich MF, Bagnol B, Prohmmo A, Smit Ja, et al. Prevalence, motivations, and adverse effects of vaginal practices in Africa and Asia: findings from a multicountry household survey. J Womens Health 2002. 2011 Jul;20(7):1097–109. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodsong C, Alleman P. Sexual pleasure, gender power and microbicide acceptability in Zimbabwe and Malawi. AIDS Educ Prev Off Publ Int Soc AIDS Educ. 2008 Apr;20(2):171–87. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esber A, Turner AN, Mopiwa G, Norris AH. Intravaginal practices among a cohort of rural Malawian women. Sex Health. 2016 Apr 14; doi: 10.1071/SH15139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myer L, Kuhn L, Stein ZA, Wright TC, Denny L. Intravaginal practices, bacterial vaginosis, and women’s susceptibility to HIV infection: epidemiological evidence and biological mechanisms. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005 Dec;5(12):786–94. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70298-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Low N, Chersich MF, Schmidlin K, Egger M, Francis SC, van de Wijgert JHHM, et al. Intravaginal practices, bacterial vaginosis, and HIV infection in women: individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2011;8(2):e1000416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardner J, Schuman K, Slattery M, Sanborn J, Abbot T, Overall J. Is vaginal douching related to cervical carcinoma? Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133(4):368–75. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarkowski Ta, Koumans EH, Sawyer M, Pierce A, Black CM, Papp JR, et al. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus infection and abnormal cytologic test results in an urban adolescent population. J Infect Dis. 2004 Jan 1;189(1):46–50. doi: 10.1086/380466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Thomas aG, Leybovich E. Vaginal douching and adverse health effects: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 1997 Jul;87(7):1207–11. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.7.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alcaide ML, Chisembele M, Malupande E, Arheart K, Fischl M, Jones DL. A cross-sectional study of bacterial vaginosis, intravaginal practices and HIV genital shedding; implications for HIV transmission and women’s health. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e009036. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brotman RM, Klebanoff MA, Nansel T, Zhang J, Schwebke JR, Yu KF, et al. Why do women douche? A longitudinal study with two analytic approaches. Ann Epidemiol. 2008 Jan;18(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassan WM, Lavreys L, Chohan V, Richardson BA, Mandaliya K, Ndinya-Achola JO, et al. Associations between intravaginal practices and bacterial vaginosis in Kenyan female sex workers without symptoms of vaginal infections. Sex Transm Dis. 2007 Jun;34(6):384–8. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000243624.74573.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watson-Jones D, Weiss HA, Rusizoka M, Baisley K, Mugeye K, Changalucha J, et al. Risk factors for herpes simplex virus type 2 and HIV among women at high risk in northwestern Tanzania: preparing for an HSV-2 intervention trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2007 Dec 15;46(5):631–42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815b2d9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baisley K, Changalucha J, Weiss HA, Mugeye K, Everett D, Hambleton I, et al. Bacterial vaginosis in female facility workers in north-western Tanzania: prevalence and risk factors. Sex Transm Infect. 2009 Sep;85(5):370–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.035543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimberlin DW, Rouse DJ. Clinical practice. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2004 May 6;350(19):1970–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp023065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, Garland SM, Morris MB, Moss LM, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect Dis. 2006 Jun 1;193(11):1478–86. doi: 10.1086/503780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaul R, Pettengell C, Sheth PM, Sunderji S, Biringer A, MacDonald K, et al. The genital tract immune milieu: an important determinant of HIV susceptibility and secondary transmission. J Reprod Immunol. 2008 Jan;77(1):32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNutt LA, WUC, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the Relative Risk in Cohort Studies and Clinical Trials of Common Outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 May 15;157(10):940–3. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruni L, Barrionuevo-Rosa L, Serrano B, Brotons M, Albero G, Cosano R, et al. Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in Malawi. Barcelona. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddy D, Njala J, Stocker P, Schooley A, Flores M, Tseng C-H, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus in HIV-infected women undergoing cervical cancer screening in Lilongwe, Malawi: a pilot study. Int J STD AIDS. 2015 May;26(6):379–87. doi: 10.1177/0956462414539149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motti PG, Dallabetta GA, Daniel RW, Canner JK, Chiphangwi JD, Liomba GN, et al. Cervical abnormalities, human papillomavirus, and human immunodeficiency virus infections in women in Malawi. J Infect Dis. 1996 Mar;173(3):714–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aboud S, Msamanga G, Read JS, Mwatha A, Chen YQ, Potter D, et al. Genital tract infections among HIV-infected pregnant women in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia. Int J STD AIDS. 2008 Dec 1;19(12):824–32. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glynn JR, Kayuni N, Gondwe L, Price AJ, Crampin AC. Earlier menarche is associated with a higher prevalence of Herpes simplex type-2 (HSV-2) in young women in rural Malawi. eLife. 2014;3:e01604. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Low A, Didelot-Rousseau M-N, Nagot N, Ouedraougo A, Clayton T, Konate I, et al. Cervical infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) 6 or 11 in high-risk women in Burkina Faso. Sex Transm Infect. 2010 Oct;86(5):342–4. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.041053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayo S, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Muñoz N, Combita AL, Coursaget P, et al. Risk factors of invasive cervical cancer in Mali. Int J Epidemiol. 2002 Feb;31(1):202–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sagay AS, Imade GE, Onwuliri V, Egah DZ, Grigg MJ, Musa J, et al. Genital tract abnormalities among female sex workers who douche with lemon/lime juice in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2009 Mar;13(1):37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alcaide ML, Jones D. Vaginal Cleansing Practices in HIV Infected Zambian Women. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):872–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0083-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner AN, Morrison CS, Munjoma MW, Moyo P, Chipato T, van de Wijgert JH. Vaginal practices of HIV-negative Zimbabwean women. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jan;2010:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2010/387671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]