Abstract

Objective

Some patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) remain sleepy despite positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy. The mechanisms by which this occurs are unclear but could include persistently disturbed sleep. The goal of this study was to explore the relationships between subjective sleepiness and actigraphic measures of sleep during the first three months of PAP treatment.

Methods

We enrolled 80 patients with OSA and 50 comparison subjects prior to treatment and observed them through three months of PAP therapy. PAP adherence and presence of residual respiratory events were determined from PAP machine downloads. Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), and actigraphic data were collected before and at monthly intervals after starting PAP.

Results

OSA subjects were sleepier and showed a greater degree of sleep disruption by actigraphy at baseline. After three months of PAP, only ESS and number of awakenings normalized, while wake after sleep onset (WASO) and sleep efficiency (SE) remained worse in OSA subjects. For OSA subjects, FOSQ improved but never reached the same level as comparison subjects. ESS and FOSQ improved slowly over the study period.

Conclusions

As a group, OSA patients show actigraphic evidence of persistently disturbed sleep and sleepiness related impairments in day-to-day function after three months of PAP therapy. Improvements in sleepiness evolve over months with more severely affected patients responding quicker. Persistent sleep disruption may partially explain residual sleepiness in some PAP adherent OSA patients.

Keywords: Obstructive sleep apnea, Residual sleepiness, Positive airway pressure, Actigraphy

1. Introduction

By providing a patent airway during sleep, positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy mitigates the recurrent obstructive respiratory events, and associated oxygen desaturations and arousals that are characteristic of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) [1]. In doing so, PAP has been shown to improve quality of life, cognitive function and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) in affected patients [2, 3, 4]. However, some treated patients still complain of being excessively sleepy. Since Guillemninault and Philip [5] first reported that some PAP-treated patients remain sleepy, questions have lingered about the causes and frequency of persistent sleepiness, and even to its existence as a problem unique to these individuals [6]. The proportion of treated patients affected by persistent sleepiness is reported to be as high as 13% [7], but different methods of assessing sleepiness yield different results. Weaver et al [8] showed that while about 20% of patients averaging 8 hours of nightly PAP use for three months were excessively sleepy as indexed by subjective measures, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), nearly half had objective evidence of sleepiness on the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT). Timing of sleep assessment is another potential factor. Sleepiness has been shown to improve within two weeks using MSLT [9] and driving simulator outcomes [10], while subjective improvement occurs more slowly [11, 12]. Finally, the nature of the residual symptoms may depend on how it is perceived by the patient; many complain of persistent fatigue, inattention or lack of a sense of well-being rather than “sleepiness” per se [13].

Intermittent hypoxia-induced cellular injury to basal forebrain and brainstem wake promoting centers has been demonstrated in mice [14] and similar injury in humans with OSA could explain some cases of persistent sleepiness. However, a more likely explanation for the majority of PAP-treated patents is inadequate adherence to PAP therapy. Weaver et al [8] demonstrated a dose-response relationship between hours of use and normalization of sleepiness; fewer hours of use were associated with a greater probability of persistent sleepiness. Patients may also remain sleepy because of residual respiratory events due to PAP under-titration or mask leaks, other coexisting sleep disorders (such as central sleep apnea and periodic leg movements), and depression [15]. Poor sleep hygiene and insufficient sleep are common in the general population and are likely to cause sleepiness in some patients with treated OSA. Moreover, there is evidence that nearly half of treated patients continue to have poor quality sleep as indexed by an elevated Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [16].

Sleep duration, timing and disruptions in sleep-wake patterns resulting in a perception of poor quality sleep are usually determined by subjective patient report, but a more objective method of determining these is with use of actigraphy. Actigraphy has been shown to be a reliable and valid method of assessing sleep-wake patterns in normal subjects, although its validity has been questioned in patients with highly fragmented sleep, such as those with OSA [17]. On the other hand, Gagnadoux [18] and Wang [19] reported close agreement between actigraphically derived sleep metrics and polysomnography in treated and untreated OSA. Otake et al [20] demonstrated short-term improvements in sleep quality assessed by actigraphy in patients after introduction of PAP, suggesting that actigraphy may be a useful means of indexing sleep duration and quality in treated patients.

The primary goals of this study were to explore the relationships between subjective sleepiness and actigraphy-derived measures of sleep duration and quality in OSA patients treated with PAP, and identify aspects of sleep recorded over an extended course of treatment that potentially predict residual sleepiness. To do so, we studied patients with a wide spectrum of OSA severity over three months, making monthly assessments of self-reported sleepiness and relating these reports to data from continuously acquired actigraphy. Subjective indices included ESS and Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ). Objective indices included total sleep time (TST), sleep fragmentation including number of awakenings (AWAKE#) and wake minutes after sleep onset (WASO), and sleep efficiency (SE). Secondary goals were to characterize the time course of changes in subjective sleepiness and sleep quality as measured by actigraphy from before to three months after introduction of PAP and to examine factors that predicted those changes. We characterized individual differences in initial status and rates of change through monthly assessments of subjective sleepiness. Quantitative indices of sleep quality from actigraphy were summarized to correspond to the timing of data collection in subjective indices. We considered several factors as predictors of post-PAP improvements in both subjective and objective sleepiness, including, pre-PAP disease severity, body mass index (BMI), and PAP-use. We elected to base recruitment of subjects solely on whether or not they met accepted clinical and polysomnographic criteria for the diagnosis of OSA rather than constraining the populations to subjects with pre-determined levels of sleepiness based upon ESS scores. This strategy ensured that the populations we studied were representative of what may be encountered in clinical practice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Eighty patients with OSA (53 male) and 50 comparison subjects (32 male) participated in a study of real-world driving safety and PAP-use. OSA patients were recruited from the University of Iowa (UI) and the Iowa City Veterans Affairs Medical Center located in eastern Iowa. OSA patients were newly diagnosed, met ICSD-2 clinical criteria for OSA [1] and had not previously been treated with PAP. Comparison subjects were recruited from the general community surrounding Iowa City through local newspapers and public service announcements. The comparison group was matched to OSA at the group level on average age (within five years) and education (within two years), with similar distributions for season of year. The comparison subjects were screened with the same procedures as those with OSA. Inclusion criteria for all participants included at least ten years of driving experience, driving a primary vehicle at least 100 miles or two hours per week, and primary vehicle make of 1996 or later.

Exclusion criteria included: a) history of a neurological disorder or sleep disorder besides OSA; b) acute illness or active, confounding medical conditions (e.g. chronic pulmonary disease requiring medical or supplemental oxygen therapy, congestive heart failure, dementia, major psychiatric and vestibular diseases, alcoholism or other forms of drug addiction); c) using stimulants, antihistamines, sedating antidepressants, narcotics, anxiolytics, anticonvulsants and other major psychoactive medications; d) consumption of >=7 cups of caffeinated beverages daily [21], e) an irregular sleep-wake pattern, working nights/rotating shifts, or a habitual sleep duration of <6 or >9 hours [22]; f) no longer driving; g) having visual field defects defined by Humphrey perimetry [23]; h) diseases of the optic nerve, retina, or ocular media coupled with a corrected visual acuity of less than 20/50.

The UI Institutional Review Board approved the study and written informed consent was obtained after full explanation of study procedures. Subjects received $500 for compensation.

2.2. Polysomnography

OSA patients had attended in-laboratory polysomnography (PSG) prior to recruitment, scored by one of two registered PSG technologists and interpreted by a board certified Sleep Medicine physician (JT). PSGs were scored according to accepted protocols and criteria [24]. Measures of apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), respiratory disturbance index (RDI), and minimum oxygen saturation (SpO2nadir) constituted disease severity indices in the analyses. Hypopneas were scored when associated with a >/=4% oxygen desaturation. The RDI was calculated as the sum of all apneas, hypopneas and respiratory effort related arousals divided by the total sleep time. Comparison subjects had unattended type-II PSG’s performed in the UI Clinical Research Unit, which were scored similarly to the in-laboratory PSG’s. OSA participants had an RDI >15 in keeping with other studies of PAP usage and daytime sleepiness (8), while controls had an RDI < 5. Results from the unattended studies were used only to screen potential control subjects and were not included in subsequent analyses.

2.3. PAP Therapy

OSA patients were started on PAP either as part of a “split-night” study or during a dedicated titration study with pressures titrated to a minimum “adequate” level [25] using a fixed pressure. The interpreting physician was responsible for the decision to use continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bi-level positive airway pressure (BPAP).

2.4. Procedure

Participants completed questionnaires two weeks before beginning PAP-therapy and at monthly intervals during the post-PAP phase [26]. Scheduling contingencies introduced significant variability into when anticipated ‘monthly’ ratings were actually obtained in both OSA and comparison subjects. Duration of study was not extended when OSA patients did not commence PAP in the anticipated timeline. Participants were given wrist actigraphy (Actiwatch Spectrum Plus, Philips Respironics, Murrysville, PA) at induction, which were worn until the end of month-3. Actigraphy data were downloaded and batteries re-charged at the monthly visits.

2.5. Measures

PAP-adherence and residual respiratory events

PAP-adherence was determined by using PAP machines with integrated microprocessors that collect usage (nightly mask-on times and durations) and residual respiratory event data (AHI by automated event detection, AHI-AED [27]). These data were saved on removable micro-SD memory cards, collected monthly from each subject. All subjects used the same type of machine from a single manufacturer to ensure comparability of data in adherence/AHI-AED. Average adherence and AHI-AED were summarized to correspond to the timing of data collection in subjective indices of sleep related functioning described next.

Excessive daytime sleepiness and functional outcomes of sleep

Participants completed the ESS [28] and FOSQ [29] during pre-PAP and monthly post-PAP visits. ESS assesses global sleepiness by asking a person to rate on a 0–3 scale the chance of dozing in eight situations. FOSQ provides a score on five subtests: general productivity, social outcome, activity level, vigilance, and intimate relationships/sexual activity. The total scores from ESS and FOSQ (sum of 5 scale scores) were used in the analyses.

Objective measures of Sleep from Actigraphy

We used daily enhanced sleep statistics including WASO, AWAKE#, SE, and TST. Actigraphy data were analyzed using the manufacturer’s proprietary software set at low threshold. Prior to data reduction, days when watch data indicated highly unlikely values were set to missing. These included the following: TST longer than 10 or shorter than 3 hours; more than 290 minutes WASO; more than 80 AWAKE#; SE less 37. Similar to how PAP data were reduced, averages for each actigraphy metric were also computed to correspond to the timing of data collection in subjective indices of sleep related functioning. Any additional extreme values (+/−3SDs) in the monthly data were winsorized to reduce the possible effects of spurious outliers.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Preliminary analyses included an examination of demographic differences between OSA and comparison groups. To ensure the inclusion/control of appropriate person-level covariates in substantive analyses, age, sex, education, BMI, and disease severity were examined as correlates of ESS, FOSQ, PAP-adherence, and AHI-AED.

The analyses were performed in three phases. In the first phase, associations among subjective indices of sleep related functioning and actigraphy were examined for the whole sample and among OSA subjects from pre-PAP to three-months post-PAP at monthly intervals. In addition, the associations of PAP-adherence and AHI-AED with subjective and actigraphic measures of sleep quality were examined at each of the three post-PAP months, and finally the associations of disease severity and BMI were examined in relation to subjective and actigraphic measures of sleep quality. The analyses in this first phase relied on Pearson product-moment correlations.

The second phase focused on quantifying patterns of change in subjective ratings and actigraphy over the course of study for both OSA and comparison subjects, and addressed whether OSA status predicted those changes over and above demographic characteristics. The third phase focused on determining how post-PAP trajectories of subjective ratings and actigraphy were affected by PAP-adherence and disease severity among OSA subjects. The analyses in the second and third phase, which involved description of change and its prediction, were addressed with mixed linear models with maximum likelihood estimation. Mixed linear models accommodate longitudinal data better than the traditional repeated measures ANOVA models [30]. In mixed linear models, time was scaled as the number of days that elapsed since PAP treatment began. This scaling permitted a consistent interpretation of time in coefficients, which included average nightly PAP-adherence as a time-varying covariate, and made explicit the amount of variability in the passage of time between consecutive ESS and FOSQ assessments in addition to total duration of the study across participants. All person-level predictors (e.g. disease severity, education) were grand-mean centered. Because disease severity indices tend to be interrelated, each disease severity index was examined individually in separate models, and because severity tends to be correlated with BMI, BMI was controlled when effects of disease severity were tested. In testing hypotheses of focused interest, both change in log likelihood of relevant nested models and significance of individual parameters were considered.

3. Results

Preliminary analyses

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for OSA and comparison subjects. There were no age differences (p = .161) or sex composition differences (p = .793) between the OSA and comparison groups. Comparison subjects were slightly better educated than those with OSA (p = .035), although the group difference in educational attainment was within our matching protocol of within two years. OSA subjects had significantly higher BMIs than comparisons (p < .001). BMI was significantly correlated with all three indices of disease severity (all p’s < .02) and was thus used as a covariate in subsequent predictive models. There were no sex differences in PAP-adherence (p’s >=.284). AHI-AED was on average lower for women than men in the first two months post-PAP (p’s < .05) but similar in month-3 (p=.244). There were no sex differences in ESS (p’s > .178), TST (p’s > .445), WASO (p’s > .161), or SE (p’s > .10). There were, however, significant sex differences in FOSQ at pre-PAP and month-3 (p’s < .017), and in AWAKE# (p’s < .010) at pre-PAP and each of the three post-PAP months. Women reported worse functioning than men on FOSQ but fewer awakenings than men.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the sample for all study variables.

| Variables | OSA | Control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | ||

| Age | 80 | 46.2 | 7.8 | 50 | 44.2 | 8.5 | |

| Education in years | 80 | 15.3 | 2.4 | 50 | 16.2 | 2.0 | |

| Disease Severity: | SpO2 nadir | 79 | 80.7 | 7.0 | ----- | ||

| AHI | 79 | 33.0 | 33.12 | ----- | |||

| RDI | 77 | 43.0 | 30.6 | ----- | |||

| BMI | 80 | 37.4 | 9.12 | 27 | 27.31 | 5.32 | |

| Timea | baseline | 68 | −4.7 | 9.9 | 50 | 0 | -- |

| month-1 | 73 | 31.0 | 7.4 | 49 | 26.6 | 5.5 | |

| month-2 | 71 | 62.6 | 14.2 | 46 | 56.1 | 9.8 | |

| month-3 | 62 | 95.9 | 18.4 | 41 | 87.7 | 8.2 | |

| PAP-adherence | month-1 | 73 | 4.49 | 2.29 | ----- | ||

| month-2 | 71 | 4.69 | 2.43 | ----- | |||

| month-3 | 62 | 4.52 | 2.64 | ----- | |||

| AHI-AED | month-1 | 71 | 3.17 | 3.11 | ----- | ||

| month-2 | 67 | 2.57 | 2.86 | ----- | |||

| month-3 | 57 | 2.82 | 3.04 | ----- | |||

| ESS | baselineb | 78 | 11.4 | 5.0 | 50 | 6.4 | 3.4 |

| month-1 | 75 | 9.1 | 4.8 | 47 | 6.9 | 4.0 | |

| month-2 | 71 | 8.3 | 4.5 | 46 | 6.4 | 3.9 | |

| month-3 | 59 | 7.0 | 4.2 | 42 | 6.5 | 3.8 | |

| FOSQ | baselineb | 68 | 91.8 | 19.1 | 47 | 108.7 | 8.2 |

| month-1 | 72 | 96.8 | 16.5 | 46 | 109.1 | 9.9 | |

| month-2 | 69 | 102.5 | 14.8 | 45 | 110.5 | 7.8 | |

| month-3 | 53 | 103.7 | 13.3 | 35 | 109.1 | 9.6 | |

| Total sleep time (minutes) | baseline | 65 | 372.2 | 61.8 | 44 | 379.0 | 43.8 |

| month-1 | 69 | 366.5 | 52.5 | 49 | 379.8 | 42.6 | |

| month-2 | 61 | 378.3 | 45.9 | 45 | 374.2 | 40.8 | |

| month-3 | 63 | 367.4 | 53.8 | 41 | 382.5 | 33.5 | |

| AWAKE# | baseline | 65 | 39.2 | 9.6 | 44 | 35.0 | 9.6 |

| month-1 | 70 | 33.8 | 9.2 | 49 | 35.3 | 9.8 | |

| month-2 | 62 | 34.7 | 9.2 | 45 | 35.6 | 9.0 | |

| month-3 | 58 | 34.0 | 10.6 | 41 | 35.1 | 9.2 | |

| WASO-minutes | baseline | 64 | 83.1 | 35.1 | 44 | 65.0 | 26.7 |

| month-1 | 70 | 81.7 | 36.4 | 49 | 64.3 | 25.0 | |

| month-2 | 62 | 72.9 | 32.9 | 45 | 71.6 | 29.4 | |

| month-3 | 58 | 79.7 | 32.2 | 41 | 62.7 | 22.2 | |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | baseline | 65 | 74.3 | 10.5 | 44 | 80.3 | 6.7 |

| month-1 | 70 | 75.3 | 9.3 | 49 | 80.3 | 6.2 | |

| month-2 | 61 | 77.2 | 8.8 | 45 | 78.4 | 7.5 | |

| month-3 | 58 | 75.2 | 8.8 | 41 | 80.6 | 5.9 | |

Abbrv. BMI= Body Mass Index RDI= Respiratory Distress Index; AHI= Apnea-Hypopnea Index; SpO2Nadir= Minimum oxygen saturation; PAP= Positive airway pressure; AHI-AED= Apnea hypopnea index by automatic event detection; ESS= Epworth Sleepiness Index; FOSQ= Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire; WASO= Wake minutes after sleep onset

Time = number of days that had elapsed since the beginning of PAP-treatment for each monthly visit, and count down of days that elapsed before PAP-therapy for baseline ESS and FOSQ.

Baseline ESS and FOSQ for OSAs reflect nearest pre-PAP assessments before PAP-therapy actually commenced. When patients began PAP later than study protocol, their ESS and FOSQ assessments were set to missing if that score reflected less than 20 days of post-PAP-therapy.

Bivariate associations among actigraphy, subjective ratings, and PAP measures

Table 2 shows the concurrent correlations among actigraphy, ESS, and FOSQ ratings from pre-PAP to three-months post-PAP at monthly intervals for the whole sample as well as the OSA subjects. SE was consistently related to FOSQ ratings, to a lesser extent the same was true for WASO, followed by TST. These associations appeared weaker for ESS in general. AWAKE# was not related to subjective ratings. Table 3 shows the concurrent correlations of PAP-adherence and AHI-AED with actigraphy, ESS, and FOSQ at monthly intervals post-PAP among OSA subjects. PAP-adherence predicted FOSQ, ESS, and SE more consistently than other measures. In contrast AHI-AED predicted AWAKE#. Table 4 shows the associations of disease severity and BMI with ESS, FOSQ, and actigraphy from pre-PAP to three-months post-PAP at monthly intervals. The correlations were strongest in the pre-PAP period and were most notable between disease severity indices and actigraphy, in particular AWAKE# and SE. SE was also consistently associated with BMI at each monthly assessment. The magnitude and number significant correlations decreased in the post-PAP assessments.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations among concurrently collected subjective and actigraphy measures of sleep quality related functioning at monthly intervals.

| TST | Awakenings | WASO | Efficiency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-papa | ||||

| ESS | −.12 (−.14) | −.15 (−.30*) | .19*(.11) | −.20*(−.09) |

| FOSQ | .19+ (.17) | .07(.29() | −.26*(−.11) | .25*(.06) |

| Month-1b | ||||

| ESS | −.16+ (−.14) | .05(.16) | .21*(.21+) | −.17+(−.12) |

| FOSQ | .23* (.20) | −.05(−.07) | −.37**(−.29*) | .34**(.21+) |

| Month-2c | ||||

| ESS | −.13 (−.21) | −.02(.01) | .04(.04) | −.09(−.08) |

| FOSQ | .11 (.14) | .06(.08) | −.16(−.13) | .23*(.17) |

| Month-3d | ||||

| ESS | −.10 (−.18) | .12(.17) | .09(.12) | −.16(−.19) |

| FOSQ | .20+ (.24+) | −.13(−.23) | −.24*(−.22) | .30**(.29*) |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p <.01 or better.

TST = Total Sleep Time WASO = Wake Minutes After Sleep Onset

Note. Parenthesized correlations are only among OSAs.

N = 96–109,

= 112–116,

N = 101–105

N = 82–91 for the whole sample.

For OSAs:

N = 55–65;

N= 66–70;

N = 59–61;

N = 50–54.

Table 3.

Pearson correlations among PAP-adherence and AHI-AED with subjective and actigraphy measures of sleep quality related functioning among OSAs.

| TST | Awakenings | WASO | Efficiency | ESS | FOSQ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month-1a | ||||||

| PAP-adherence | .45** | −.20 | −.09 | .30* | −.23* | .27* |

| AHI-AED | −.12 | .38** | .22+ | −.20 | −.03 | .09 |

| Month-2b | ||||||

| PAP-adherence | .25+ | −.26* | .03 | .20 | −.26* | .26* |

| AHI-AED | −.16 | .27* | .09 | −.18 | .02 | .14 |

| Month-3c | ||||||

| PAP-adherence | .26+ | −.25+ | −.01 | .27* | −.20 | .38** |

| AHI-AED | .18 | .25+ | −.06 | .12 | −.09 | .15 |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p <.01 or better.

TST = Total Sleep Time WASO = Wake Minutes After Sleep Onset

N = 67–73

N = 58–69

N = 49–58

Table 4.

Pearson correlations among BMI, disease severity indices with subjective and actigraphy measures of sleep related functioning.

| AHI | RDI | Spo2Nadir | BMI (for OSA only) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-papa | ||||

| ESS | .05 | −.02 | −.12 | .23* (.00 ) |

| FOSQ | .05 | .10 | .05 | −.33** (−.11) |

| TST | −.21 | −.17 | .16 | −.22* (−.28*) |

| AWAKE# | .47** | .43** | −.25* | .06 (−.16) |

| WASO | .24+ | .17 | −.23+ | .30** (.18) |

| SE | −.44** | −.39** | .30** | −.40** (−.29*) |

| Month-1b | ||||

| ESS | .10 | .09 | −.11 | .00 (−.12) |

| FOSQ | .01 | .07 | −.01 | −.27** (−.12) |

| TST | −.10 | −.10 | −.01 | −.08 (−.05) |

| AWAKE# | .29* | .27* | −.06 | −.10 (−.19) |

| WASO | .14 | .10 | −.02 | .16+ (.06) |

| SE | −.27* | −.25* | .06 | −.25** (−.13) |

| Month-2c | ||||

| ESS | −.03 | −.02 | −.05 | .00 (−.09) |

| FOSQ | .21+ | .23+ | −.13 | −.06 (.10) |

| TST | −.12 | −.10 | .12 | −.07 (−.15) |

| AWAKE# | .36** | .33** | −.19 | −.02 (−.06) |

| WASO | .12 | .06 | −.16 | .15 (.19) |

| SE | −.29* | −.25+ | .27* | −.25* (−.29*) |

| Month-3d | ||||

| ESS | −.03 | −.05 | −.13 | −.13 (−.14) |

| FOSQ | .20 | .30* | −.10 | .04 (.14) |

| TST | −.02 | .02 | .12 | −.10 (−.04) |

| AWAKE# | .24+ | .24+ | .02 | −.09 (−.18) |

| WASO | 16 | .10 | −.21 | .23* (.10) |

| SE | −.21 | −.19 | .21 | −.28** (−.13) |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p <.01 or better.

TST = Total Sleep Time WASO = Wake Minutes After Sleep Onset, AHI= Apnea-Hypopnea Index, RDI = Respiratory Distress Index, BMI = Body Mass Index

N = 62–77

N = 67–74

N = 59–70

N = 52–58 for correlations based only on OSAs

Patterns of change in actigraphy, subjective ratings, and PAP measures

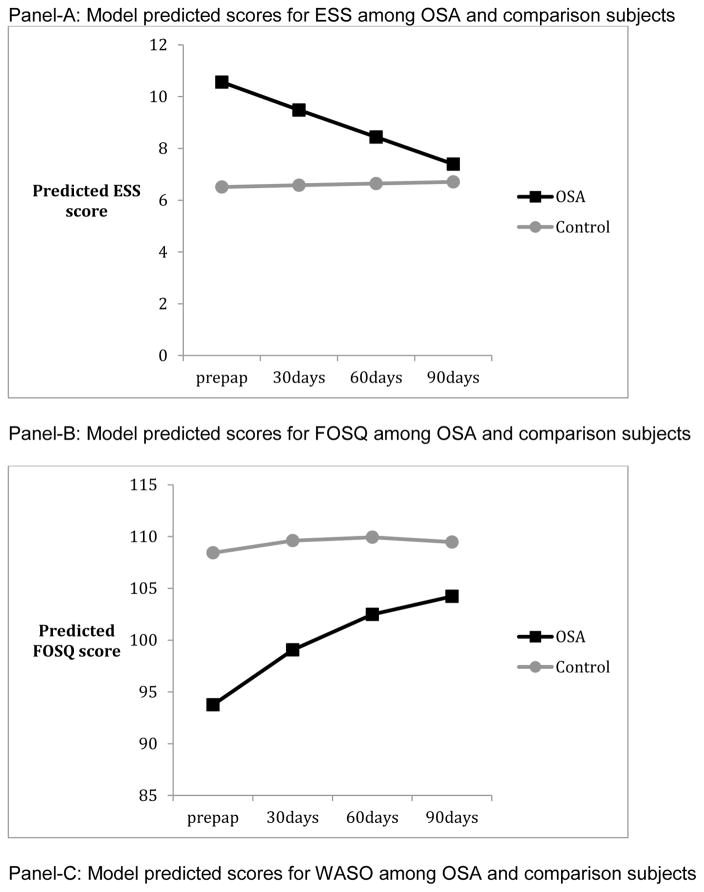

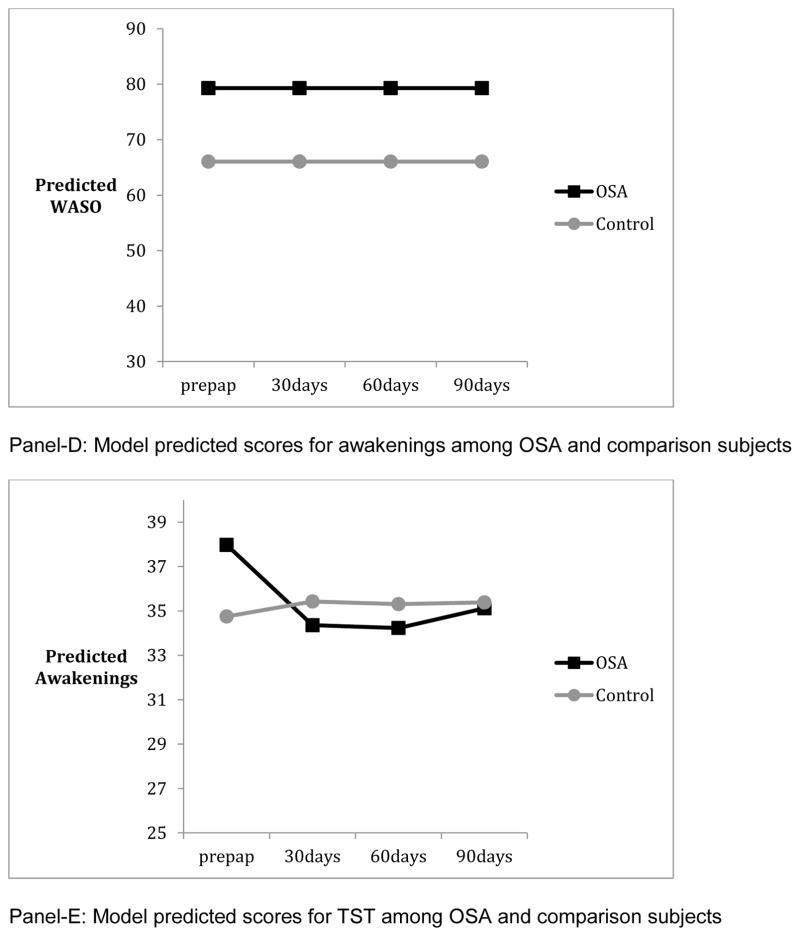

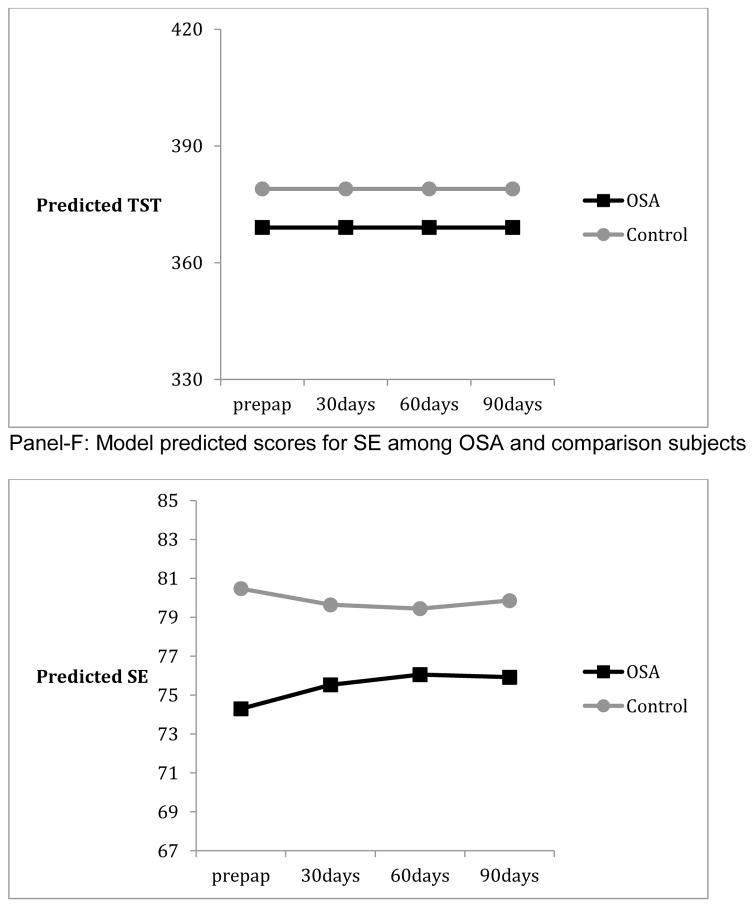

Panels of Figure 1 summarize the results from mixed linear models, and depict the model predicted values from pre-PAP to post-PAP in ESS, FOSQ, and actigraphy among OSA and comparison subjects. Those with OSA showed worse functioning than comparison subjects at pre-PAP on all measures except TST (p’s <. 04). Patterns of change from pre-PAP to post-PAP periods necessitated the inclusion of quadratic terms for FOSQ, AWAKE#, and SE but not ESS, TST, or WASO. There were significant individual differences in both intercept and linear rate of change (p’s <.01 for random variance components) for all measures except WASO and SE. By the end of the three-month period, OSA subjects were not significantly different from comparisons in ESS and AWAKE# (p’s > .824). However OSA subjects continued to show lower functioning in FOSQ (p = .047) and lower SE (p= .005) than comparisons at month-3. The group differences in initial levels and/or patterns of change from pre-PAP to post-PAP months remained significant when demographic characteristics such as educational achievement (for FOSQ), sex (for FOSQ and AWAKE#), and age (for WASO) were added to the models. Finally, the percentage of OSA patients who reported significant daytime sleepiness (ESS >=10) was reduced from 60% to 17% from pre-PAP to month-3 post-PAP whereas the percentage of comparison participants who reported significant daytime sleepiness remained similar at 14% across the same time period. As there are no universally accepted normative criteria for FOSQ, it was not possible to define the proportion of subjects who remained “impaired” by that tool. PAP-adherence had significant linear and quadratic patterns of change but random components of variance for change or the intercept were not significant (p’s > .608). AHI-AED showed no significant change over the course of three months of PAP (p’s > .289).

Figure 1.

Predictors of post-PAP changes among OSA subjects

We also modeled changes in actigraphy, ESS, and FOSQ as a function of PAP-adherence, disease severity, and BMI among OSA subjects in the post-PAP months. We parameterized these mixed linear models so that effects of within-person monthly fluctuations as well as between-person differences in PAP-adherence could be examined separately [31]. Because each of the three disease severity indices was highly correlated, models were constructed separately for AHI, RDI and SpO2Nadir. Furthermore, all models included demographic characteristics that predicted differences in the outcomes in the group-based modeling analyses.

The initial baseline models among OSA subjects in the post-PAP months were generally similar in shape to those described earlier that also included data from comparison subjects, e.g. a linear term was sufficient for ESS but a quadratic term was necessary for FOSQ. Prior to testing to the effects of PAP-adherence or disease severity on post-PAP changes among the subjective and actigraphic measures among OSA subjects, BMI was entered as a covariate. The effects of BMI on the initial response and/or the pattern of changes over time to PAP-therapy was not statistically significant for ESS, TST, AWAKE#, WASO, and SE (p’s > .18). BMI showed a marginally significant effect on FOSQ. Specifically, it tended to predict rate of change over time in FOSQ (p = .078), but not the initial response to PAP (p = .402).

Even if BMI’s influence was not significant for a given outcome measure, it was retained in all subsequent models to statistically minimize confounding while testing the effects of disease severity on the outcome measures. The addition of the PAP-adherence terms reflecting respectively the month-to-month within-person fluctuation and the between-person differences in overall level or person average significantly improved model fit for ESS, FOSQ, TST, and SE (p’s < .027) but not for AWAKE# or WASO (p’s > .213). These improvements reflected the effects of PAP on the initial response to treatment (e.g. intercept). PAP-adherence never predicted the rate of change in the outcome measures (p’s > .10).

Whether PAP-adherence met the criteria for statistical significance or not, we kept the terms reflecting PAP’s effect on the initial response to treatment for all outcomes measures in subsequent model fitting analyses to probe the effects of disease severity. These analyses involved fitting a sequence of two nested models testing the following hypotheses: a) severity only predicts initial response to PAP and b) severity predicts both initial response to PAP and the subsequent rate of change. These models were repeated for each of the three disease severity indices. The findings showed that the addition of AHI, RDI and SpO2Nadir all contributed significantly to prediction of initial response to PAP (p’s < .001) for all six measures. AHI (p’s < .035) and RDI (p’s < .034) predicted the rates of change in ESS and AWAKE#, while Spo2Nadir predicted the rates of change in AWAKE# (p = .002) in the post-PAP months. Rate of improvement tended to be steeper for those with more severe disease.

4. Discussion

The primary goals of this study were to explore the relationships between subjective sleepiness and actigraphy-derived measures of sleep duration and quality in OSA patients following initiation of PAP, and identify aspects of sleep recorded over an extended course of treatment that potentially predict residual sleepiness. To that end we examined associations among subjective indices of sleepiness and objective measures of sleep using actigraphy from pre-PAP to three-months post-PAP, described the course of changes in these indices, and examined PAP-adherence and disease severity as predictors of those changes. To our knowledge this is the first study to use actigraphy as a means of assessing sleep in treated OSA patients over an extended period of time.

As there are no existing data on what constitutes disrupted sleep from actigraphy recorded over three months of continuous use, we elected to employ a statistical approach to define disruption in OSA subjects relative to normal comparisons. Not surprisingly, we found that OSA subjects differed from comparisons in both subjective sleepiness and most actigraphic measures of sleep at baseline and in some aspects of sleepiness after three months of treatment. However, while subjective measures improved over time we found actigraphic evidence of persistent sleep disruption after three-months of PAP. At baseline, OSA patients had a higher number of nocturnal awakenings, lower SE and higher WASO than controls, while there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of TST. After one month of PAP, the number of awakenings improved in the OSA group and remained similar to comparison subjects thereafter. On the other hand, there was no improvement in WASO and only limited improvement in SE. This suggests that the duration of nocturnal awakenings was longer in the OSA group. Of note, OSA subjects on average were adherent with the typical 4-hour nightly use recommendation and the low AHI-AED indicated that respiratory events were effectively suppressed. Otake et al [20] also found improvement in the number of awakenings in their PAP treated subjects but unlike our findings showed clear improvements in SE. They did not analyze WASO. However, they studied fewer subjects (n = 18) and used a paradigm in which actigraphy was performed over three consecutive days before and one month after starting PAP rather than continuously over three months. Our finding of persistent sleep disruption is consistent with that of Veauthier [16] who found that approximately half of the treated OSA subjects they studied remained poor sleepers as indexed by the PSQI.

An interesting observation from our data is that subjective measures of sleepiness improve gradually. It took three months for the OSA subjects to reach the same ESS scores as comparisons and while their FOSQ scores steadily improved over the study period, they never achieved the same level as the comparison group. Studies in which objective measures of sleepiness are repeatedly assessed have reported improvements within the first few days following initiation of PAP, which plateau within two to six-weeks [9, 10]. Less is known about the time-course of change in subjective measures over an extended period as most previous studies have only compared two endpoints –before and one to three-months after starting PAP. However, Orth et al [10] showed improvement in the ESS between assessments at two and 42 days of PAP therapy while most objective measures had reached a plateau. Along similar lines, Bakker et al [12] showed that the psychomotor vigilance task (PVT) and mean sleep latency improved from baseline to one month post-PAP but were unchanged at three months, while ESS and FOSQ improved over the entire study period.

The differential response we observed between ESS and FOSQ has been reported by others. Weaver et al [8] showed that at all levels of PAP adherence a smaller proportion of subjects had normalized FOSQ scores compared to ESS at the end of three months, and while four hours of use appears adequate to reach maximum improvement in ESS, seven hours of use is necessary for FOSQ [2]. The discrepant findings for ESS and FOSQ may reflect the fundamental difference in the nature of FOSQ and ESS items; FOSQ directs the rater to specifically attribute difficulty with daytime functioning to excessive sleepiness. Hence, improvements in FOSQ might be expected to lag behind those for excessive daytime sleepiness. Alternatively, PAP may simply be more effective in controlling a treated patient’s tendency to doze-off when sedentary than improving their sense of general well-being or ability to function in daily activities that require sustained concentration. This interpretation is supported by a more detailed examination of the correlations in Table 4 by FOSQ subscales. For example, the correlations of SE and WASO in the post-PAP months with FOSQ’s general productivity, social outcomes, sexual function, and activity level were consistently fair to moderate and statistically significant. In contrast, the corresponding correlations of SE and WASO with the vitality subscale, which is closest in item content/meaning to ESS, were weaker and often not significant in that time period. These findings are consistent with reports that OSA patients often endorse feelings of fatigue or a lack of well-being rather than sleepiness per se [13], which may be reflected to a greater degree in indices weighted more towards quality of life issues, such as FOSQ.

Disease severity (especially AHI/RDI) consistently predicted the initial response to PAP for all subjective and objective measures in the post-PAP period. That is, those with more severe disease showed larger initial improvements in response to PAP, in line with other studies showing that more severely affected patients generally experience greater improvement following introduction of PAP [32]. Moreover, as we measured treatment responses at monthly intervals, we were able to make the novel observation that disease severity also predicts the rate of improvement in ESS and number of awakenings. Not only do more severely affected individuals have a greater response to treatment, they improve more rapidly.

Our findings showed generally small to moderate correlations between subjective measures and actigraphy from before PAP to three-months after PAP. Sleep efficiency and WASO were the most consistently associated with FOSQ ratings, while the magnitude of associations was generally weaker for ESS. There was no indication that the correlations were stronger among OSA subjects compared to those based on the whole sample. PAP-adherence but not effectiveness (AHI-AED) showed concurrent associations with ESS, FOSQ, total sleep time, and SE. Number of awakenings showed consistent associations with AHI-AED indicating that despite being in the “acceptable” range for patients on PAP [27], a larger number of respiratory events remain associated with a larger number of actigraphy-detected awakenings. This is explained by the observation that while the mean value of awakenings for the OSA group became statistically similar to comparison subjects by month-1, patients with more severe disease at baseline continued to have a larger number of awakenings compared to those with less severe disease. Of note, measures of disease severity showed moderate associations with actigraphy but not subjective indices prior to PAP, and disease severity continued to predict actigraphic findings, especially SE in the post-PAP months. The weak to moderate convergence between subjective and objective indices suggests that disrupted sleep as measured by WASO and SE may play at least a partial role in causing persistent sleepiness in some PAP-treated OSA patients.

There are several mechanisms by which persistent sleep disruption might occur in treated OSA patients. Studies in patients [33] and animal models of OSA [14, 34] have demonstrated the presence of structural changes in areas of the brain involved in sleep-wake regulation, suggesting the possibility that brain injury could explain the sleep disruption we observed. However, both in humans and animals, investigators have typically found increased sleepiness without disrupted sleep, and these studies focused on patients with severe OSA or animals subjected to repeated bouts of marked hypoxemia, while our subjects generally had more moderate OSA. Depression and anxiety are common clinical manifestations of OSA that are often associated with poor sleep quality [35] and may only partially respond to PAP therapy [36]. However, we excluded subjects with uncontrolled psychiatric disorders at recruitment and while no formal assessments were made at follow up visits, there was no evidence of persisting psychological issues in our subjects. Although persistent respiratory events has been posited as a potential cause of residual sleepiness in OSA, the mean AHI-AED of our subjects was well within the range considered reflective of good treatment efficacy [27]. That being said, the persisting relationship we observed between AHI-AED and number of awakenings suggests that some patients may remain inadequately treated, requiring higher pressures or correction of mask leaks, despite having an “acceptable” AHI-AED. Perhaps the most plausible explanation is that PAP therapy itself is at least partially responsible. In one study nearly 50% of patients started on PAP continued to complain of nocturnal awakenings attributed to PAP after more than a year of therapy [37]. The most common treatment related issues in this group were mucosal dryness, ear and eye pain (due to poor mask fit), aerophagia and claustrophobia. Other side effects that may negatively impact sleep include pressure intolerance, difficulty exhaling and air leaks through the mouth [38]. Hence, PAP itself, despite controlling the obstructive respiratory events characteristic of OSA, may be sufficiently intrusive for some patients to disrupt their sleep continuity.

Our study had several limitations. First, our sample sizes may have been too small to detect statistically significant relationships between actigraphy and subjective sleep measures. Second, our OSA subjects were not particularly sleepy at baseline (mean ESS 11.4). As greater baseline sleepiness pre-PAP has been shown to predict response to treatment [32], it is not surprising that our findings were not more robust. Our study did not include an enriched population of overtly sleepy OSA patients as these observations were taken from a larger study of driving performance in a population with a broad range of pre-PAP disease severity and we did not restrict subject recruitment to patients with elevated ESS scores at baseline. As mentioned previously, we intentionally used this recruitment strategy to ensure that the populations we studied were similar to what clinicians encounter in practice. However, despite the fact that the mean ESS for the group was only mildly elevated at baseline and not different from controls after three months of treatment, FOSQ was considerably worse at baseline and never reached the control level. Finally, differences between OSA and comparison subjects may have been made more difficult to detect because our control group’s sleep was suboptimal; their total sleep time was only a little over 6 hours. However, this is a societal trend that is common in the general population [39] and probably impossible to completely control for in studies such as this.

5. Conclusions

We found persistently disturbed sleep quality using actigraphy in OSA patients after three months of seemingly adequate PAP therapy. In addition, these patients continued to have evidence of continued sleepiness related impairments in day-to-day functioning, although overt sleepiness had largely resolved. Of particular note, the improvements in sleepiness took time to develop with more severely affected patients responding more quickly. Awareness of this gradual improvement is key in determining appropriate timing of reassessment and making appropriate comparisons of data obtained at different follow up intervals. Our observations suggest a possible relationship between continued sleep disruption and some features of residual sleepiness in patients treated with PAP. The mechanism by which sleep disruption occurs is unknown, but may be speculated to be due in part to the intrusive nature of PAP therapy itself. Improving PAP delivery systems and paying careful attention to potentially correctable PAP related problems could lead to better sleep quality and less daytime sleepiness.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Some actigraphic measures of sleep quality remain disturbed in OSA patients after three months of therapy in PAP-adherent individuals.

Overt sleepiness as indexed by ESS normalizes with PAP but patients continue to have evidence of sleepiness related quality of life impairments by FOSQ.

Subjective symptoms as reported in ESS and FOSQ improve slowly after introduction of PAP.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

This study was funded by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL091917-01A2).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kushida CA, Littner MR, Hirshkowitz M, et al. Practice parameters for the use of continuous and bilevel positive airway pressure devices to treat adult patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Sleep. 2006;29:375–80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antic NA, Catcheside P, Buchan C, et al. The effect of CPAP in normalizing daytime sleepiness, quality of life and neurocognitive function in patients with moderate to severe OSA. Sleep. 2011;34:111–19. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett LS, Langford BA, Stradling JR, et al. Sleep fragmentation indices as predictors of daytime sleepiness and nCPAP response in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:778–86. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9711033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDaid C, Duree KH, Griffin SG, et al. A systematic review of continuous positive airway pressure of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13:427–36. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guilleminault C, Philip P. Tiredness and somnolence despite initial treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (what to do when an OSAS patient stays hypersomnolent despite treatment) Sleep. 1996;19:S117–22. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.suppl_9.s117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stradling JR, Smith D, Crosby J. Post-CPAP sleepiness—a specific syndrome? J Sleep Res. 2007;16:436–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pepin JL, Viot-Blanc V, Escourrou P, et al. Prevalence of residual excessive sleepiness in CPAP-treated sleep apnoea patients: the French multicentre study. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1062–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00016808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weaver TE, Maislin G, Dinges DF, et al. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep. 2007;30:711–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.6.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamphere J, Roehrs T, Wittig R, et al. Recovery of alertness after CPAP in apnea. Chest. 1989;96:1364–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.6.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orth M, Herting A, Duchna HW, et al. Driving simulator performance in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: what consequences for driving capability? Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2005;130:2555–60. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-918602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aksan N, Tippin J, Dawson J, et al. Improvements in actigraphy-derived sleep metrics following PAP-therapy in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2014;37:A106. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakker J, Campbell A, Neill A. Randomized controlled trial comparing flexible and continuous positive airway pressure delivery: effects of compliance, objective and subjective sleepiness and vigilance. Sleep. 2010;33:523–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.4.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chervin RD. Sleepiness, fatigue, tiredness, and lack of energy in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2000;118:372–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veasey SC, Davis CW, Fenik P, et al. Long-term intermittent hypoxia in mice: protracted hypersomnolence with oxidative injury to sleep-wake brain regions. Sleep. 2004;27:194–201. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Launois SH, Tamisier R, Levy P, et al. On treatment but still sleepy: cause and management of residual sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;(19):601–8. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328365ab4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veauthier C. Poor versus good sleepers in patients under treatment of sleep-related breathing disorders: better is not good enough. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:131–3. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S58970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgenthaler T, Alessi C, Friedman L, et al. Practice parameters for the use of actigraphy in the assessment of sleep and sleep disorders: an update for 2007. Sleep. 2007;30:519–29. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gagnadoux F, Nguyen XL, Rakotonanahary D, et al. Wrist-actigraphic estimation of sleep time under nCPAP treatment in sleep apnoea patients. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:891–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00089604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang D, Wong KK, Dungan GC, et al. The validity of wrist actimetry assessment of sleep with and without sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:450–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otake M, Miyata S, Noda A, et al. Monitoring sleep-wake rhythm with actigraphy in patients on continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Respiration. 2011;82:136–41. doi: 10.1159/000321238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh JK, Muehlbach MJ, Humm TM, et al. Effect of caffeine on physiological sleep tendency and ability to sustain wakefulness at night. Psychophysiol. 1990;101:271–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02244139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aeschbach D, Postolache TT, Sher L, et al. Evidence from the waking electroencephalogram that short sleepers live under higher homeostatic sleep pressure than long sleepers. Neuroscience. 2001;102:493–502. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00518-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson AJ, Johnson CA. Mechanisms isolated by frequency-doubling technology perimetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:398–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, et al. for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kushida CA, Chediak A, Berry RB, et al. Positive Airway Pressure Titration Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical guidelines for the manual titration of positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:157–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tippin J, Aksan N, Dawson J, et al. Neuroergonomics of sleep and alertness. In: Proctor R, Johnson A, editors. Neuroergonomics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2013. pp. 110–27. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berry RB, Kushida CA, Kryger MH, et al. Respiratory event detection by a positive airway pressure device. Sleep. 2012;35:361–7. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weaver TE, Laizner A, Evans LK, et al. An instrument to measure functional status outcomes for disorders of excessive sleepiness. Sleep. 1997;20:835–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singer J, Willet J. Applied longitudinal analysis: modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Ann Rev Psychol. 2011;62:583–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel SR, White D, Malhotra A, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure therapy for treating sleepiness in a diverse population with obstructive sleep apnoea: results of a meta-analysis. Arch Int Med. 2003;163:565–71. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macey PM, Henderson LA, Macey KE, et al. Brain morphology associated with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1382–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200201-050OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu Y, Fenik P, Zhan G, et al. Selective loss of catecholaminergic wake active neurons in a murine sleep apnea model. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10060–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0857-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bahammam AS, Kendzerska T, Gupta R, et al. Comorbid depression in obstructive sleep apnea: an under-recognized association. Sleep Breath. 2015 Jul 9; doi: 10.1007/s11325-015-1223-x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta MA, Simpson FC, Lyons DCA. The effect of treating obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure on depression and other subjective symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;28:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffstein V, Viner S, Mateika S, et al. Patient compliance, perception of benefits and side effects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:841–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.4_Pt_1.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aloia MS, Stanchina M, Arnedt JT, et al. Treatment adherence and outcomes in flexible vs standard continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Chest. 2005;127:2085–93. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Sleep Foundation. [Accessed November 5, 2015];Sleep in America Poll. 2005 https://sleepfoundation.org/sleep-polls-data/sleep-in-america-poll/2005-adult-sleep-habits-and-styles.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.