Abstract

Variations in the dosage of social interventions and the effects of dosage on program outcomes remain understudied. This study examines the dosage effects of the Chicago School Readiness Project, a randomized, multifaceted classroom-based intervention conducted in Head Start settings. Using a principal score matching method to address the issue of selection bias, the study finds that high-dosage levels of teacher training and mental health consultant class visits have larger effects on children’s school readiness than the effects estimated through intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses. Low-dosage levels of treatment are found to have effects that are smaller than those estimated in ITT analyses or to have no statistically significant program effects. Moreover, individual mental health consultation services provided to high-risk children are found to have statistically significant effects on their school readiness. The study discusses the implications of these findings for research and policy.

Research suggests that program participation is a critical source of variance in the outcomes associated with early childhood interventions. Exposure to different levels of services provided (hereafter described as dosage) can reveal whether such interventions yield statistically significant benefits (Shonkoff and Phillips 2000; Hill, Brooks-Gunn, and Waldfogel 2003). Investigators favor randomized experiments as the gold standard for evaluation of programs in which treatment and control groups have similar observed and unobserved characteristics (Hill et al. 2003; Peck 2003; Agodini and Dynarski 2004; Smith and Todd 2005; Lochman et al. 2006). Nevertheless, due to participants’ noncompliance with randomized assignments, most experimental interventions involving human subjects suffer from complications (Barnard et al. 2003; Peck 2003). Moreover, many social interventions provide multifaceted program services, and evaluation can be difficult because, in addition to the issue of noncompliance, participants are also exposed to different subcomponents of these interventions, which make it difficult to isolate the respective individual effects of the various subcomponents. The analyses of differentials in participants’ dosage levels may have serious implications for policy makers and program administrators. However, the empirical issue of self-selection limits the study of those matters because, after random assignment, individual members of the treatment group can make choices about whether to receive, and the extent to which they receive, the intervention services.

To address the issues of noncompliance and self-selection existing in social experiments, the current study investigates the dosage effects of an early childhood intervention program. Specifically, it employs data from the Chicago School Readiness Project (CSRP), a randomized, multifaceted classroom-based intervention conducted in Head Start settings. These data are analyzed to examine the effects of differential dosage levels of the CSRP intervention on children’s school readiness. The study also considers whether those dosage effects vary by subcomponents of the CSRP intervention. The study employs innovative analytic methods to address the issue of selection bias.

Background and Prior Research

Preschool is an important setting for early childhood education outside the home. Approximately 60 percent of 4-year-olds in the United States enroll in some form of preschool prior to kindergarten (Webster-Stratton and Taylor 2001; Waldfogel 2006). Substantial research suggests that preschool is an effective setting for preventive interventions designed to reduce children’s behavioral problems and to promote their cognitive development. Findings also suggest that such interventions are particularly effective for economically disadvantaged children who face high risk of developing social-emotional difficulties and have limited access to mental health services (Raver 2002; Lochman and Wells 2003; Webster-Stratton, Reid, and Hammond 2004; Smolkowski et al. 2005; Wong et al. 2008).

Some studies identify benefits of classroom-based interventions that focus on providing preschool teachers with training and consultations with mental health professionals. These interventions are found to improve classroom management strategies, overall child-care quality, the quality of teacher-child interactions, teachers’ self-efficacy, and their competence in dealing with difficult children (Alkon, Ramler, and Mac-Lennan 2003; Webster-Stratton et al. 2004). Such improvements in teachers’ skills are found, in turn, to benefit the development of low-income children.

For instance, recent randomized experiments and quasi-experiments adopt the Incredible Years Training Series, a classroom-based multifaceted intervention designed to prevent and treat behavior problems in young children (ages 3–8). These studies find that training preschool teachers in classroom management strategies is associated with reductions in children’s disruptive behaviors. Classroom-based mental health consultation, designed to facilitate the implementation of these strategies, is found to be positively related to children’s improvement in social competence and adaptation (Webster-Stratton, Reid, and Hammond 2001; Reid, Webster-Stratton, and Hammond 2003; Shernoff and Kratochwill 2007; Williford and Shelton 2008). Moreover, research also suggests that individualized, child-focused mental health consultation statistically significantly increases social skills and reduces behavior problems among preschool children with social-emotional difficulties. Such consultation also reduces the probability that a child will be expelled from a child-care center (Perry et al. 2008).

Findings from such randomized controlled trials represent important steps forward for the fields of policy analysis and prevention science, but most of these recent studies only provide intention-to-treat (ITT) estimates for the average treatment effects of classroom-based interventions. As a conventional and rigorous test of program effects, ITT analysis compares the average outcomes of the treatment group with those of the control group. However, the comparison does not consider whether or not participants actually comply with assigned intervention conditions or to what extent they comply (Gibson 2003; Peck 2003; Angrist 2006; Lochman et al. 2006). Thus, ITT analysis has important policy relevance, as it provides estimates of program effects on the population for which the intervention is intended (Webster-Stratton et al. 2001; Peck 2003).

Nevertheless, another critical policy issue to consider is that real-world conditions of program implementation often differ from the aspirations of researchers and policy makers. Many participants do not comply with their assigned treatment conditions and do not take up or fully receive the intervention services (see review by Peck 2003). For example, studies on parenting training programs in preschool settings, including those on programs adopting the Incredible Years Training Series, report that about one-third of parents assigned to the treatment group never attend a session; from 12 percent to more than 50 percent of parents attend less than half of the sessions (Barkley et al. 2000; Webster-Stratton et al. 2001). As a result, ITT estimates may be substantially lower than the actual effects of interventions if participants were to fully comply with the treatment assignments, and the ITT estimates may not even be statistically significant in some circumstances in which the intervention potentially is effective (Barkley et al. 2000; Gibson 2003; Hill et al. 2003; Angrist 2006; Lochman et al. 2006). In addition, many social interventions, such as the Incredible Years Training Series, offer multifaceted services. However, few studies estimate the program effects of these individual components, and there is little guidance on best approaches that might be taken to empirically model the benefits of subcomponent services when they are bundled together in a single package of treatment (Gibson 2003; Peck 2003).

Answers to these empirical questions on program dosage effects have pressing policy relevance. Budget constraints often force resource allocation decisions that attempt to balance program intensity or duration with the number of participants served. If a higher dosage level is found to be associated with better program outcomes, policy makers may be motivated to increase program intensity or duration rather than the number of families or individuals served (Lu et al. 2001). For example, some descriptive evidence suggests that the duration of preschool teachers’ training and consultations with mental health professionals predicts both teachers’ self-efficacy and child outcomes (Alkon et al. 2003; Green et al. 2006; Brennan et al. 2008). Conversely, if intervention program outcomes resulting from high-dosage levels are similar to those from low-dosage levels, the marginal returns from high dosage may be relatively low or negligible. As a result, policy makers may consider allocating resources to focus on the number of individuals served rather than on the intensity or duration of existing interventions.

In addition, the issue of self-selection is a major impediment to the investigation of program dosage effects. Because participants can choose whether to take part in treatment (or its subcomponents) after random assignment, and the extent to which they participate, the dosage level of program participation is often associated with the pretreatment characteristics of individual members of the treatment group (Hill, Waldfogel, and Brooks-Gunn 2002; Gibson 2003; Hill et al. 2003; Peck 2003; Lochman et al. 2006). For example, studies on parenting training programs in preschool settings report that treatment group parents who do not attend or drop out of the programs tend to be younger, at lower family risk, and less educated than those who attend or continue in the interventions; their children also tend to have fewer behavior problems at baseline (Barkley et al. 2000; Webster-Stratton et al. 2001). These pretreatment covariates are also associated with children’s developmental outcomes (Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, and Aber 1997; Li-Grining et al. 2006; Zhai, Brooks-Gunn, and Waldfogel, forthcoming). As a result, simply comparing the outcomes of individuals who receive different dosage levels of interventions may lead to biased estimates of dosage effects.

Modeling the role of dosage is additionally complicated in the context of randomized trials, because individuals in the control group are generally not given the option to enroll in the treatment, and their level of participation (or their dosage levels) therefore cannot be observed directly. Nevertheless, evidence from the treatment group in a randomized experiment, as the discussion above mentions, suggests that only a subgroup of the control-group-assigned participants would actually take up or fully complete the program if it were offered to them (Frangakis and Rubin 2002; Gibson 2003; Peck 2003). As a consequence, biased estimates of dosage effects may result from simple comparisons of the outcomes of individuals with different dosage levels, including those in the entire control group (Bickman, Andrade, and Lambert 2002; Hill et al. 2003; Peck 2003; Lochman et al. 2006).

Recently, several methods have been designed to estimate program dosage effects and to address the issue of self-selection. These methods use either matching or weighting strategies. Two of them directly model the dosage of treatment. One such method uses a single scalar balancing score estimated by an ordered logistic regression for multiple dosage levels. It then conducts nonbipartite pair matching (i.e., in contrast to bipartite matching between treatment and control groups) based on the estimated distance scores (Joffe and Rosenbaum 1999; Lu et al. 2001; Guo and Fraser 2009). The goal of this method is to identify pairs of cases that are similar in terms of observed covariates but very different in terms of dosage levels. Another approach uses a multinomial logit model to estimate multiple balancing scores. The inverse of a specific, generalized propensity score is then used as sampling weight to conduct an outcome analysis (i.e., analysis with propensity score weighting; Imbens 2000; Guo and Fraser 2009).

A third method, matching estimators, is widely used in evaluation research. This approach does not model treatment dosage directly and does not use logistic regressions to predict propensity scores. Instead, it uses a vector norm (calculated by either the inverse of the sample variance matrix or the inverse of the sample variance-covariance matrix) to estimate the distances on observed covariates between treated and control cases. It then estimates the differences in outcomes between the treated and control cases that have the shortest distances (Abadie and Imbens 2002, 2006; Guo and Fraser 2009). Since the approach of matching estimators imputes a potential outcome for each study unit, it is possible to estimate the average treatment effects for user-defined subsets of units. For example, Shenyang Guo and Mark Fraser (2009) employ the matching estimators method to evaluate the treatment effects of program dosage in a randomized intervention that involved a skills-training curriculum for elementary school students in North Carolina.

These evaluation methods offer a number of methodological advantages. Research suggests that they are effective and robust tools for the evaluation of the treatment effects of program dosage (Imbens 2000; Lu et al. 2001; Guo and Fraser 2009). However, these methods may not be directly applicable to the analysis of data from relatively small randomized trials that involve multilevel treatment units, as is the case in the current study.

In particular, these methods that directly model dosage of treatment use either a single scalar balancing score estimated by an ordered logistic regression or multiple balancing scores estimated by a multinomial logit model. Results from observational studies suggest that, because all individuals in both treatment and control groups are exposed to treatment, their dosage levels of participation may vary from no dosage to high levels; they also may reflect other defined levels (e.g., Imbens 2000; Lu et al. 2001; Guo and Fraser 2009). In contrast, control group participants in randomized interventions are not exposed to treatment. However, one should not assume that the potential dosage levels would be zero for all control group members. The dosage levels in the control group would also vary in a similar way as those in the treatment group if control group participants had been randomly assigned to the treatment condition. Therefore, it would be inappropriate to directly conduct dosage analyses using ordered or multinomial logistic models on the full sample (i.e., including both treatment and control groups) of a randomized intervention.

In addition, the current study’s small sample limits the ways in which dosage levels can be defined for participants in the treatment group. This study therefore relies on a dichotomized measure (i.e., low or high dosage), rather than on use of a scale with multiple dosage levels, to empirically characterize participation. This limitation also prevents this study from using ordered or multinomial logistic models to conduct dosage analyses with only the treated group. Matching estimators is a promising method for use in dosage analyses because it is intuitively appealing and easy to implement (Abadie and Imbens 2002, 2006; Guo and Fraser 2009). However, this study must also consider the issue of clustering, because the matching estimators method does not correct for inefficiency induced by clustering (Guo and Fraser 2009). The current version of the matching estimators approach is not suitable for this study’s dosage analyses, because the study relies on data from a clustered randomized trial with multilevel treatment units.

Principal stratification and subgroup analysis provide an alternative means to address the issue of selection bias in studying the dosage effects of multifaceted social interventions (Frangakis and Rubin 2002; Hill et al. 2002, 2003; Barnard et al. 2003; Gibson 2003; Peck 2003). A few studies examine the dosage effects of interventions on young children’s developmental outcomes by employing such analytic approaches as principal score matching, propensity score matching, complier average causal effect models, and instrumental variables estimation. Most of these studies find that dosage levels are positively associated with intervention effects. For example, some analyses find no ITT effects but statistically significant treatment effects among minimal-level compliers (Lochman et al. 2006). In addition, some estimates suggest that the relation between dosage levels and intervention effects is larger and longer lasting among high-level compliers than among their minimally compliant counterparts (Angold et al. 2000; Hill et al. 2003).

The Present Study

This study adopts a principal score matching method to address the issue of selection bias in program dosage analyses. It investigates the dosage effects of the CSRP intervention, examining three key indicators of children’s school readiness: teacher-reported behavior problems, observer-reported emotional and behavioral self-regulation skills, and observer-rated cognitive development. In addition, this study examines whether the dosage effects vary across school readiness measures and the individual components of the CSRP intervention.

Previous research finds that the CSRP has statistically significant ITT effects on children’s school readiness outcomes. These effects include reductions of children’s behavior problems as well as improvements in social-emotional skills and cognitive development (Raver et al. 2009; Raver et al., forthcoming). These findings and results from evaluations of other interventions that target young children at risk lead the authors to identify four hypotheses. First, this study posits that the estimated treatment effects for children who received high doses of the CSRP intervention will be larger than corresponding ITT estimates. Second, it posits that the estimated effects for children with low doses of treatment will be smaller than ITT estimates or that the estimates will be statistically nonsignificant. Third, the dosage effects are posited to differ across measures of school readiness. Fourth, this study hypothesizes that dosage effects will vary across individual components of the CSRP intervention.

Method

CSRP Participants and Intervention

The CSRP focuses on teachers of ethnic minority preschoolers, on enhancing the quality of emotional support provided by these teachers, and on helping them to build effective classroom management strategies. These efforts are intended to support children’s development of self-regulation, reduce their risk of behavioral difficulty, and increase their opportunities for learning (Raver et al. 2009). The CSRP randomly assigns two cohorts of Head Start program children and teachers into a multifaceted classroom-based intervention. These two cohorts come from seven of the most economically disadvantaged neighborhoods in Chicago. Cohort 1 participated in the intervention from fall 2004 to spring 2005. Cohort 2 participated from fall 2005 to spring 2006. Data for each cohort were collected at two points: September (pretreatment) and May (posttreatment) of the Head Start year.

The CSRP adopts a clustered, randomized controlled trial (RCT) design and a pairwise matching procedure (Bloom 2005) to recruit participants and assign them into treatment and control groups. In particular, the study first chooses 18 Head Start sites that have two or more classrooms and provide full-day services in the seven economically disadvantaged Chicago neighborhoods. The 18 sites are then matched into nine pairs based on a range of site-level demographic characteristics that each site collects and reports annually to the federal government. One site in each matched pair is then randomly assigned to the treatment group, and the other to the control group. Each site initially included two randomly selected classrooms. After randomization, one classroom left the study due to Head Start funding cuts. In total, CSRP participants include 602 children and 90 teachers in 35 classrooms at 18 Head Start sites.

The data collected in September of the Head Start year using questionnaires for parents and teachers show that, on average, participating children in the CSRP are 4 years old, and about half are boys. Approximately 66 percent of participating children are non-Hispanic black, 26 percent are Hispanic, and 8 percent are members of other racial or ethnic groups. On average, sampled teachers reported that they were 40 years old at the cohort’s baseline interview (September of the Head Start year), and almost all teachers (97 percent) are female. About 70 percent of teachers identify themselves as non-Hispanic black, 20 percent identify as Hispanic, and 10 percent identify themselves as non-Hispanic white.

The CSRP intervention in the treatment group includes three service components. The first component is a 30-hour teacher training that focuses on behavior management strategies. These strategies are adapted from the Incredible Years teacher training module (Webster-Stratton et al. 2004). All treatment-assigned teachers, including head teachers and assistant teachers, were invited to participate in the five 6-hour training sessions, which were held on Saturdays from September to March during the Head Start year. The participation was voluntary. The incentives for teachers to participate in the training sessions included a compensative payment at a rate of $15 per hour, catered lunches, and on-site child care.

The second component of the CSRP intervention is the placement of mental health consultants (MHCs) into treatment group classrooms. These clinically trained MHCs held master’s degrees in social work and had experience working with young children from low-income families. Attending classes one morning per week, these MHCs coach teachers in implementing behavior management strategies and support them in the use of specific techniques to promote children’s positive emotion and behavioral development. They also provide ongoing stress management consultation to help teachers deal with work-related stress. The stress reduction strategies that the MHCs provide are tailored to teachers’ individual needs.

The third component of the CSRP intervention involves individual mental health consultation services for a small number of children (three to four children per class) in the treatment group. Children who receive these services have high emotional and behavioral problems, as identified by the MHCs based on their clinical judgment, consultation with teachers, and review of teacher-reported measures of children’s behavioral problems in September of the Head Start year. These children receive individualized, direct intervention services from the MHCs, including individual and group therapies. The services were provided from March to May in the Head Start year.

To ensure that the child-staff ratio is similar across treatment and control classrooms, the CSRP provided an aide to teachers in the control group. These teachers’ aides only provided staffing support during everyday classroom activities and were present in the control group classrooms for the same amount of time per week as the MHCs were in the treatment group classrooms.

Measures

Outcome variables

Children’s school readiness is the primary outcome measured in this study. It is measured by behavioral, social-emotional, and cognitive scales completed by teachers and independent observers. As previous research suggests, teachers’ reports concerning child outcomes may be biased by knowledge of children’s treatment status (Barkley et al. 2000). The study therefore adopts scales completed by both teachers and observers. Observers are graduate students and full-time research staff who have at least a bachelor’s degree. They are not informed of the treatment status of the subjects to whom they are assigned. Observers conduct one-on-one assessment of children in their schools.

The measures of school readiness include teacher-reported behavior problems, observer-reported social-emotional skills, and observer-rated cognitive development. These scales provide standardized measures of young children’s school readiness. They are used extensively in large-scale policy evaluations as well as in smaller efficacy trials of educational and clinical interventions (e.g., Hill et al. 2002, 2003; Love et al. 2002; Yeung, Linver, and Brooks-Gunn 2002; Puma et al. 2005; Spencer et al. 2005; Hooper and Bell 2006; Markowitz et al. 2006; Cathers-Schiffman and Thompson 2007).

Children’s behavior problems are measured by the Behavior Problem Index (BPI). The BPI captures teachers’ responses to questions adapted from a 28-item rating scale originally designed for parents to report the types of child behavior problems (Zill 1990). The study uses the scales for internalizing and externalizing problems. Following recommendations from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (Zill 1990), the authors sum items to form two domains: internalizing (α = .80) and externalizing (α = .92).

Children’s social-emotional skills are reported by observers using the Preschool Self Regulation Assessment-Assessor Report (Smith-Donald et al. 2007). This measure includes 28 items and is adapted from the Leiter-R social-emotional rating scale (Roid and Miller 1997) as well as from the Disruptive Behavior-Diagnostic Observation Schedule coding system (Wakschlag et al. 2005). The measure provides a global picture of children’s emotions, attention, and behavior throughout assessor-child interaction. Data obtained through the social-emotional skills measure are aggregated into two subscales: attention and impulse control (α = .93) and positive emotion (α = .84). The attention and impulse control subscale measures whether children pay attention during instructions and demonstrations and whether they think and plan before beginning each task. The positive emotion subscale measures whether children are interactive and show pleasure and confidence during activities.

Children’s cognitive development is reported by observers using the third edition of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) and a measure of early math skills. A shortened version of the PPVT, using a 24-item scale (α =.78), asks children to identify one out of four pictures that correspond to the word or action indicated by the observer (Dunn and Dunn 1997; Zill 2003b). The early math skills measure (α = .82) consists of 19 items reported by observers that cover basic addition and subtraction (Zill 2003a).

Dosage measures

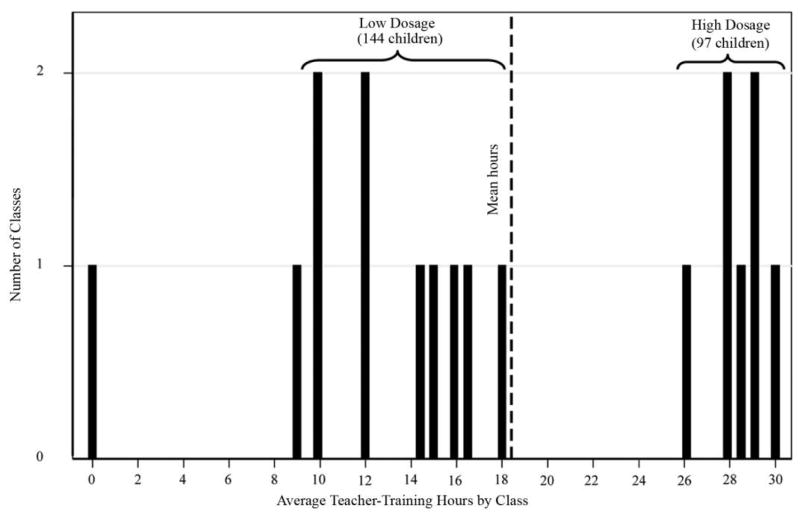

This study relies on three measures of dosage: the hours of teacher training, the hours of MHC class visits, and whether children received individual mental health consultation services. The measures correspond to the three components of the CSRP intervention. Not all teachers in the treatment group completed the 30-hour training sessions. Figure 1 shows the average hours of training received by each of 18 CSRP treatment group classes (i.e., the per-class average reflects hours of training received by all teachers in that class). On average, teachers in each class received 18 hours of training (standard deviation [SD] is 9 hours). As figure 1 shows, all of the teachers in one treatment group class did not attend any training session; teachers in the remaining treatment group classrooms received between 9 and 30 hours of training.

Fig. 1.

Average teacher-training hours by class

Prior research on the Incredible Years Training Series suggests that attendance of less than half of an intervention is an inadequate dosage level (Webster-Stratton et al. 2001). Figure 1 suggests that, among CSRP teachers who received any training, there are two distinct groups. One group represents teachers in classes for which the hours of received training are concentrated right below the mean. On average, teachers in these classrooms received 9–18 hours of training. Hours received by this group account for 30–60 percent of the total training hours provided by the CSRP. The second group represents classes with teachers who received all or nearly all of the 30 hours of training provided by CSRP. On average, classes in this group received 26–30 hours of training. This accounts for between 87 and 100 percent of the total training hours provided by CSRP. The 8-hour gap (27 percent of the total training) between the ranges of average teacher training hours in these two groups is considerable. The first group is therefore defined as the low-dosage training group. This group represents 28 teachers in 10 classes. The classes serve 175 children. The second is defined as the high-dosage training group. It represents 18 teachers in seven classes; these teachers serve 114 children.

Similarly, the number of hours that MHCs visit classes ranges from 100 to 152 hours per class (the mean is 128 hours; SD is 18 hours), and two distinct groups are discernible: MHC visits of 100–126 hours and visits of 132–52 hours. For this study, the former group is defined as the low-dosage MHC group. It comprises 123 children in eight classrooms. The second group, identified by MHC visits between 132 and 152 hours, is designated the high-dosage MHC group. It comprises 185 children in 10 classrooms. The estimates suggest that the two groups are separated by a 6-hour gap between their ranges of MHC visits.

The third dosage measure is a dichotomous indicator of whether or not a child received any individual mental health consultation services provided by the MHCs. Previous research suggests that the number of hours of mental health consultation per child in early childhood settings is not statistically significantly associated with reductions in children’s behavior problems or with improvement in social competence (Green et al. 2006). Only a small number of children (n = 137) in the CSRP treatment group received any individual mental health consultation services. The study therefore treats exposure to individual mental health consultation services as an extra dose of the CSRP intervention, in addition to the services of teacher training and MHC class visits, for this group of children who have high emotional and behavioral problems.

The three dosage measures are relatively independent of each other and have very weak correlations. For example, the correlation coefficient (r) between high-dosage teacher training and high-dosage MHC class visits is estimated to be 0.07. The coefficient for the correlation between high-dosage teacher training and receipt of individual mental health consultation services is 0.01. The coefficient for the correlation between high-dosage MHC class visits and individual mental health consultation services is 0.09. Therefore, these dosage measures can be investigated separately to estimate their respective effects on children’s outcomes under the assumptions that participants also received the services of other components of the CSRP intervention and that those services were distributed equally or randomly. It should be noted that the findings on the dosage effects of individual components should be interpreted in the context of the CSRP’s multifaceted services. Because all children received the treatment of teacher training and MHC class visits and some children also had individual mental health consultation services, the dosage effects of individual components reported in this study might be larger than those of individual components if the components were provided separately.

Baseline covariates

The covariates in this study include the characteristics of children, teachers, classrooms, and sites at the time of the baseline interview (i.e., September of the Head Start year). Results from many preventive interventions targeting low-income children suggest the importance of disaggregating the potential confounders of child and family demographic characteristics (see, e.g., Aber, Brown, and Jones 2003; Tolan, Gorman-Smith, and Henry 2004; Schaeffer et al. 2006). In this study, child-level covariates include child gender, race or ethnicity, poverty-related family risks, whether the child is from a single-parent family, whether his or her parents speak Spanish during the CSRP data collection, and children’s pretreatment scores in September for corresponding outcome variables in May. Child race or ethnicity is coded as whether the child is non-Hispanic black, since the majority of children in the CSRP are reported to be either non-Hispanic black (66 percent) or Hispanic (26 percent). The measure of poverty-related family risks is a sum of three risk factors: whether the mother holds less than a high school diploma, whether family income-to-needs ratio is less than half the federal poverty threshold, and whether the mother works 10 or fewer hours per week. Previous analyses with large, nationally representative data sets suggest that these covariates represent the most reduced and informative set of indicators for families’ exposure to deep poverty (Raver, Garner, and Smith-Donald 2007). This study employs a multiple imputation method to address the issue of missing data on child-level covariates. The procedure is detailed in the appendix.

In addition, recent research suggests that the ways in which interventions work may differ with institutional resources and teacher motivation (Gottfredson, Jones, and Gore 2002). Thus, the current analyses include a set of teacher- and class-level covariates that are intended to function as proxies for teaching as well as for classroom quality and environment. Specifically, teachers’ personal stressors are indexed by six self-reported risks. These risks include whether they have less than an associate’s degree, 3 or fewer years of preschool teaching experience, and depressive symptoms, as well as whether they are single, the primary income earner in their household, or live with four or more minors. Data on teachers’ personal stressors are collected through a questionnaire derived from the Cornell Early Social Development Study (Raver 2003). In addition, four items examine teachers’ work-related stressors. The assessed stressors include feelings of high job demand, lack of confidence in managing classrooms, low job control, and low job resources. Three of the stressors (i.e., job demand, job control, and job resources) were based on the Child Care Worker Job Stress Inventory (CCW-JSI; Curbow et al. 2000). The CCW-JSI is designed to capture child-care providers’ self-reported assessments of job stress. Another work-related stressor (i.e., lack of confidence) is adopted to measure teachers’ beliefs regarding the causes of children’s behavior as well as their confidence in handling misbehavior (Scott-Little and Holloway 1992; Hammarberg and Hagekull 2002). Classroom quality is assessed using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS; La Paro, Pianta, and Stuhlman 2004) and the revised edition of the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (ECERS-R; Harms, Clifford, and Cryer 2005). Indicators from the CLASS use a 7-point Likert scale to measure teacher sensitivity and behavior management. Teacher sensitivity measures how responsive teachers are to children’s academic and emotional needs. Teacher behavior management is an indicator of how well teachers monitor, prevent, and redirect children’s behaviors in class. Based on 43 items, the ECERS-R is a widely used research tool that measures early childhood classroom quality across a wide range of constructs. In addition, the number of children observed in each classroom is used to control for the potential confounding effects of differences in class size. So too, a variable that measures the number of adults observed in each classroom is used as a control for differences in child-to-staff ratios.

Analytic Strategy

Propensity score matching is increasingly used to address selection bias in evaluating the effects of early childhood intervention programs (see research and reviews by Shonkoff and Phillips 2000; Hill et al. 2002, 2003, 2005; Lochman et al. 2006; Schneider et al. 2007; Guo and Fraser 2009; Zhai et al., forthcoming). A conventional propensity score matching approach uses observed pretreatment covariates to estimate the probability (i.e., the propensity score) that an individual will be assigned to the treatment group. The analysis then matches each member in the treatment group with the one or more control group members whose propensity scores are closest. There are several matching methods (e.g., nearest neighbor, radius, kernel, and Mahalanobis methods). If the analysis assumes that the predictive covariates are the only confounding variables, it can conceptualize these matched individuals with similar propensity scores as if they are randomly assigned to the treatment or control group in an experiment (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983, 1985; Heckman, Ichimura, and Todd 1997; Dehejia and Wahba 1999, 2002; Hill et al. 2002; Gibson 2003; Schneider et al. 2007).

This study uses a principal score matching method to match children in the control group with those who received high- or low-dosage treatment from the multifaceted CSRP intervention. Principal score matching is a method derived from propensity score matching, It builds on recent methodological innovations in principal stratification and subgroup analysis in the context of randomized experiments (Frangakis and Rubin 2002; Hill et al. 2002, 2003; Barnard et al. 2003; Gibson 2003; Peck 2003). Because two of the CSRP’s three components (i.e., teacher training and MHC class visits) are provided at the class level, the strategy employed to analyze the class-level data differs from the strategy used to analyze data on the mental health consultation services provided individually to a small number of children.

Specifically, the analyses of the two class-level components of the CSRP intervention (i.e., teacher training and MHC class visits) include four stages. In the first stage, the study estimates the propensity of each treatment group classroom, j, to actually receive high- or low-dosage CSRP treatment (D). This first stage is conducted with the logit model specified in equation (1):

| (1) |

where Cj represents the pretreatment teacher and class characteristics in classroom j that possibly influence the class’s propensity to receive high- or low-dosage CSRP treatment. These variables were collected prior to the CSRP intervention. The characteristics include teachers’ personal stressors, work-related stressors, sensitivity, and behavior management; overall classroom quality (measured by ECERS-R scores); class size; and the number of adults in the classroom.

Using the coefficients obtained from equation (1), the study then estimates the dosage propensity scores for classrooms in the control group. These dosage propensity scores are referred to as principal scores, because they are used to stratify the population into mutually exclusive subgroups (or principal strata), which are based on pretreatment variables (Frangakis and Rubin 2002; Hill et al. 2003). Propensity scores differ from principal scores in the ways that they are estimated. In general, conventional propensity score matching involves an observed binary variable that indicates whether participants were in either the treatment or control group. Thus, the propensity scores estimated by a logit, logistic, or probit regression refer to the probabilities that all participants in the sample will receive the treatment of a program. In principal score matching, by contrast, control group participants’ memberships in principal strata or subgroups (i.e., receiving high- or low-dosage services) cannot be observed directly (Frangakis and Rubin 2002; Gibson 2003; Peck 2003). Therefore, the analyses first estimate the treatment group’s respective propensities to receive high- and low-dosage treatment (Hill et al. 2003). The resulting parameters are then applied to participants in the control group in order to estimate the respective probabilities that they would receive high- and low-dosage treatment if they were assigned to the treatment group. These estimates are based on control group members’ observed pretreatment characteristics, Cj (Hill et al. 2002, 2003; Gibson 2003; Peck 2003). Principal score matching is therefore appropriate for adjusting for such posttreatment variables as program dosage (Frangakis and Rubin 2002; Hill et al. 2003).

In the second stage, the principal scores estimated in the first stage are used to match classrooms in the treatment group with those control group classrooms that have the closest principal scores. The CSRP’s RCT design ensures that classrooms in the treatment and control groups generally have similar characteristics, and these similarities make it possible to find control-treatment matches for classrooms with differential dosage levels (Hill et al. 2002, 2003; Peck 2003). The procedure uses a one-to-one nearest neighbor matching method. The analysis assumes that the predictors in equation (1) are the only confounding variables. Each pair of matched classrooms has similar principal scores, and thus the two matched classes in each pair are comparable in terms of the likelihood of receiving high- or low-dosage treatment (under the hypothetical condition that both were assigned to the treatment group).

Once the classrooms are matched, one intuitively appealing approach would be to continue the analyses at the class level and to estimate the dosage effects of treatment by comparing the average scores of children in pairs of matched classrooms. However, this approach faces additional challenges. Such an approach does not account for the variation in class-level treatment effects across individual children. Previous research finds that the CSRP treatment effects are moderated by child characteristics (e.g., gender, race or ethnicity, and poverty-related risk; Raver et al. 2009). In addition, comparing outcomes of matched classroom pairs is challenging because the study has a small sample of classrooms (i.e., 35 classrooms in total), and the numbers of classrooms in the high-and low-dosage treatment groups are also quite small (e.g., 10 classes in the low-dosage teacher training group and seven in the high-dosage group). These sizes offer little statistical power to detect effects (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). Finally, comparing outcomes of matched classes is challenging because the focus of this study falls on the effects of CSRP intervention dosage on child school readiness outcomes. The intraclass correlations from unconditional three-level models (Lee 2000; Guo 2005; Trouilloud et al. 2006; Hedges and Hedberg 2007) suggest that the vast majority of variance in child outcomes is attributable to child-level heterogeneity (i.e., 73–78 percent in teacher-reported behavior problems and 83–95 percent in observer-rated social-emotional and cognitive scales). Therefore, child characteristics are likely to play a substantial role in children’s school readiness. They also are likely to affect teachers’ attendance at training sessions and MHCs’ class visits. Matched models should therefore include child characteristics (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983, 1985; Dehejia and Wahba 1999, 2002; Hill et al. 2002).

In the third stage, individual children in the matched classrooms are matched on their pretreatment characteristics. This step attempts to further account for child-level heterogeneity and is represented in equation (2):

| (2) |

where Tijk stands for the treatment status of child i in classroom j of matched classroom pair k (i.e., T = 1 as treatment, T = 0 as control), and Xijk represents the child’s pretreatment characteristics. These characteristics include gender, race and ethnicity (i.e., non-Hispanic black or not), poverty-related family risks, whether the child is from a single-parent family, whether his or her parents speak Spanish, and scores on pretreatment behavioral, social-emotional, and cognitive instruments. The fixed effect, ϕk, of matched classroom pair k represents the matching of children in the treatment group with control group counterparts who had similar pretreatment characteristics (conducted within the matched classrooms during the second stage). This procedure uses a one-to-one nearest neighbor matching method with replacement. Matching with replacement can minimize biases in estimates, because it allows each treatment unit to be matched with the nearest control unit, the latter of which can be matched again (i.e., matching with replacement) if it is the best match for other treatment units. Thus, the method produces higher match quality and is less sensitive to the order of units than matching without replacement (Abadie and Imbens 2002, 2006; Dehejia and Wahba 2002; Gibson 2003; Guo and Fraser 2009). Among children in the control group who had the same principal scores, one is chosen randomly for matching, and any nonmatched controls are discarded from further analysis (i.e., less than 3 percent in this study; Dehejia and Wahba 1999, 2002; Gibson 2003).

In the fourth stage, the dosage effects of the CSRP are estimated by calculating the regression-adjusted differences in the outcomes of matched children. Regression adjustment is increasingly used to estimate treatment effects in randomized experiments as well as in principal and propensity score matching methods. If one includes covariates in regression models after matching, one can reduce some bias from the matching by adjusting for the remaining differences in covariates among matched children. This approach also allows the investigator to take into account the effects of covariates on outcomes rather than to attribute differences in children’s outcomes only to differences in their dosage levels of program participation (Abadie and Imbens 2002, 2006). As a result, adjusting for covariates after matching or randomized assignment can reduce potential bias and increase the chance of detecting statistically significant treatment effects (Rubin and Thomas 2000; Hill et al. 2002; Gibson 2003; Hill et al. 2003; Puma et al. 2005; Zhai et al., forthcoming). Regression adjustment after matching also reduces the chances of misspecification in the models because adjustments are made for relatively small differences in the covariates (Lu et al. 2001; Abadie and Imbens 2002, 2006). Therefore, ordinary least squares regressions are used to estimate the dosage effects of the CSRP in the sample of matched children. These estimates, which control for the pretreatment covariates of children, teachers, and classrooms, are presented in equation (3):

| (3) |

where Oijk represents the outcomes of child i in classroom j of matched classroom pair k, Dijk stands for a binary variable of dosage measure (1 = high or low dosage; 0 = matched control), Xijk denotes child characteristics, Cjk represents the covariates of teacher and class in classroom j, ϕk is a fixed effect of matched classroom pair k (showing that the comparison of outcome difference is among matched children who were in the same matched classrooms from the second stage), and ξijk is a random error term. Huber-White robust standard errors are adopted to account for the cluster feature of children nested in classrooms. Because the matching method employs replacement in the third stage, the analysis also applies weights to equation (3); weights are calculated as the number of times that matched control units are used (Dehejia and Wahba 1999, 2002; Hill, Reiter, and Zanutto 2004; Zhai et al., forthcoming).

In contrast to the approach employed in the four-stage dosage analyses of the CSRP’s two class-level components (i.e., teacher training and MHC class visits), a slightly different strategy is adopted for the dosage analyses of the child-level CSRP component (i.e., mental health consultation services for individual children). Because the individual MHC services are provided at the child level for a small number of children in all of the treatment group classrooms, principal score matching is conducted in three stages. In the first stage, equation (1) is used to estimate the propensities of children in the treatment group to receive individual MHC services. These propensities are estimated from children’s pretreatment characteristics as well as from teacher and classroom covariates. Parameters obtained from equation (1) are then applied to children in the control group in order to estimate the probability that each receives individual mental health consultation services if he or she is assigned to the treatment group. In the second stage, the principal scores from the first stage are employed to match children who receive individual mental health consultation services to those in the control group who have similar principal scores. This step uses a one-to-one, nearest neighbor matching method with replacement. To account for Head Start site-level heterogeneity, children are matched within the same matched pairs of Head Start sites that the CSRP originally designed. Finally, in the third stage, regression-adjusted differences are employed (as specified in eq. [3]) to estimate the effects of individual mental health consultation services. In analyzing these effects on children’s school readiness outcomes, individual mental health consultation services are treated as an extra dose of the CSRP intervention on children’s school readiness outcomes.

The processes of estimating principal scores and matching are performed separately for low- and high-dosage treatment of two CSRP components (i.e., teacher training and MHC class visits) as well as for the extra dose of whether children received individual mental health consultation services. In a conventional propensity score matching approach, each individual person is associated with one propensity score that represents his or her probability of being treated. By contrast, the dosage analyses of the three CSRP components estimate principal scores for each individual person. Each individual’s principal scores reflect his or her estimated propensities for specific dosage levels of treatment in each of the three CSRP components. This approach enables the analysis to estimate separately the respective dosage effects of individual components (Peck 2003).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics on covariates by treatment condition and matching status. It also reports the significance levels from t-tests of the full control (column a: control group before matching) sample’s differences from the treated samples (columns b: low- and high-dosage teacher training, low- and high-dosage MHC class visits, individual mental health consultation services). Significance levels for these tests are indicated in columns b. The table also presents the mean differences between the treated columns (columns b) and the matched columns (columns c: control groups after matching). The significance levels for these tests are indicated in columns c.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics by Treatment Condition and Matching Status

| Full Sample |

Full Control (a) |

Teacher Training

|

MHC Class Visits

|

Individual MHC

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Dosage

|

High Dosage

|

Low Dosage

|

High Dosage

|

|||||||||

| Treated (b) |

Matched Control (c) |

Treated (b) |

Matched Control (c) |

Treated (b) |

Matched Control (c) |

Treated (b) |

Matched Control (c) |

Treated (b) |

Matched Control (c) |

|||

| Child and family characteristics: | ||||||||||||

| Sample size | 602 | 294 | 175 | 175 | 114 | 114 | 123 | 123 | 185 | 185 | 137 | 137 |

| Boy | .47 | .44 | .54+ | .48 | .50 | .45 | .52+ | .47 | .50 | .48 | .62** | .55 |

| Non-Hispanic black | .66 | .65 | .81** | .84 | .39** | .51+ | .79** | .85 | .58 | .65 | .71 | .70 |

| Poverty-related risks | 1.08 | .99 | 1.26** | 1.17 | .91 | 1.02 | 1.44** | 1.30 | .98 | .93 | 1.21* | 1.10 |

| Single-parent family | .69 | .67 | .75* | .77 | .61 | .64 | .74 | .75 | .68 | .73 | .69 | .72 |

| Speaking Spanish | .23 | .25 | .17* | .15 | .28 | .34 | .16+ | .17 | .24 | .26 | .18+ | .20 |

| Pretreatment scores: | ||||||||||||

| BPI internalizing scale | 2.24 | 1.99 | 2.16 | 2.03 | 3.06** | 3.08 | 2.01 | 1.98 | 2.78** | 2.21 | 2.89** | 2.19+ |

| BPI externalizing scale | 5.72 | 5.17 | 5.91 | 5.82 | 7.08** | 6.60 | 6.32+ | 5.77 | 6.20* | 5.99 | 8.19** | 7.74 |

| Attention and impulse control | 2.15 | 2.10 | 2.17 | 2.19 | 2.21 | 2.17 | 2.15 | 2.10 | 2.24* | 2.18 | 2.15 | 2.14 |

| Positive emotion | 1.91 | 1.88 | 1.95 | 2.01 | 1.93 | 1.82 | 1.97 | 2.01 | 1.93 | 1.89 | 1.98 | 1.98 |

| PPVT | 10.33 | 9.98 | 10.22 | 10.10 | 11.35** | 10.77 | 10.81+ | 10.35 | 10.56 | 10.52 | 10.63 | 9.90 |

| Early math skills | 7.07 | 6.70 | 7.49* | 7.27 | 7.43 | 7.62 | 7.64* | 7.17 | 7.29 | 7.03 | 6.99 | 7.02 |

| Teacher and classroom characteristics: | ||||||||||||

| Sample size | 35 | 17 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 18 | 17 |

| Teacher personal stressors | 2.59 | 2.45 | 3.08+ | 2.75 | 2.33 | 2.02 | 3.04+ | 2.94 | 2.48 | 2.42 | 2.73 | 2.45 |

| Teacher work stressors | 1.23 | 1.30 | 1.10 | 1.27 | 1.21 | 1.15 | 1.48 | 1.46 | .92 | 1.25 | 1.17 | 1.30 |

| Teacher behavior management | 4.92 | 5.18 | 4.21* | 4.52 | 5.30 | 5.40 | 4.21* | 4.52 | 5.04 | 5.10 | 4.67 | 5.18 |

| Teacher sensitivity | 4.82 | 5.11 | 4.26+ | 4.51 | 4.91 | 5.21 | 4.54 | 4.62 | 4.57 | 5.06 | 4.56 | 5.11 |

| Classroom overall quality | 4.75 | 4.97 | 4.08** | 4.35 | 5.22 | 5.09 | 4.81 | 4.95 | 4.34* | 4.67 | 4.55 | 4.97 |

| Class size | 16.03 | 16.00 | 16.80 | 15.70 | 14.71 | 14.43 | 15.13 | 15.25 | 16.80 | 16.00 | 16.06 | 16.00 |

| No. adults in classroom | 2.29 | 2.21 | 2.03 | 2.28 | 2.86+ | 2.46 | 1.95 | 2.06 | 2.70+ | 2.53 | 2.37 | 2.21 |

Note.—MHC =mental health consultant; BPI =Behavior Problem Index (internalizing and externalizing scales); PPVT =Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test III. Means in respective samples: child and family covariates in child-level samples and teacher and classroom covariates in class-level samples; p-values represent results for two-tailed t-statistics testing the Full Control column’s (col. a; i.e., control group before matching) differences from the Treated columns (cols. b), as well as the Treated columns’ (cols. b) mean differences from the Matched Control columns (cols. c; i.e., control groups after matching). Significance levels for the Full Control column’s (a) differences from the Treated columns (b) are presented in the Treated columns; levels for differences between the Treated (b) and Matched Control (c) columns are presented in the Matched Control columns.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

As the results in table 1 suggest, children in the low-dosage teacher training sample are more likely to be boys (54 percent) than are children in the full control group before matching (44 percent). The estimates also suggest that children in this low-dosage sample are more likely to be non-Hispanic black (i.e., 81 vs. 65 percent in the full control group) and to live with single parents (75 vs. 67 percent in the full control group). They are estimated to have more poverty-related risks (1.26 vs. .99 in the full control group) and higher pretreatment scores on early math skills. They are estimated to be less likely to have parents who speak Spanish (i.e., 17 vs. 25 percent in the full control group). The estimates further suggest that the classrooms in the low-dosage teacher training group tend to have teachers with more personal stressors (3.08) than do classrooms with teachers in the control group (2.45). So, too, teachers in the low-dosage classrooms are estimated to have lower behavior management skills (4.21 vs. 5.18) and less sensitivity (4.26 vs. 5.11); overall, the classrooms are of lower quality (4.08 vs. 4.97) than the control group classrooms.

By contrast, the estimates suggest that children in the high-dosage teacher training group are more likely than those in the full control group to be in some racial or ethnic category other than non-Hispanic black. Children in the high-dosage group also are estimated to have higher pretreatment scores on BPI internalizing and externalizing scales as well as on the PPVT. The results suggest that the high-dosage teacher training classrooms tend to have more adults than those in the full control group.

Compared to classrooms in the full control group, the treatment group classrooms that received low-dosage MHC class visits are estimated to have more boys and non-Hispanic black children. The estimates suggest that children in those low-dosage classrooms have more poverty-related risks and higher pretreatment scores on the BPI externalizing scale, the PPVT, and the measure of early math skills. Classrooms that received low-dosage MHC class visits also are estimated to have teachers with more personal stressors and lower behavior management skills than do the teachers in the control group classrooms.

Children in classrooms that received high-dosage MHC class visits are found to have higher pretreatment scores on the BPI internalizing and externalizing scales than do children in the full control group classrooms. Their scores on the attention and impulse control subscale are also found to be higher. The overall quality of classrooms that received high-dosage MHC class visits is estimated to be lower than that of control group classrooms, but classrooms with high doses of MHC visits are estimated to have more adults. Finally, compared with children in the full control group, treatment group children who received individual mental health consultation services are estimated to be more likely to be boys; they are found to have more poverty-related risks and higher pretreatment scores on both BPI scales. In all treatment group classrooms, the number of children who received individual mental health consultation services is small. The estimates suggest that the teacher and classroom characteristics of children who received these individual services do not differ to a statistically significant degree from the teacher and classroom characteristics of children in the full control group. This actually is an overall comparison between the full treatment and the full control groups, since all treatment-assigned classes have children receiving individual mental health consultation services.

The results in table 1 also suggest that principal score matching leaves few statistically significant differences between matched control (cols. c) and treated (cols. b) groups. After matching, marginally significant mean differences (at p < .10) are found for two variables; non-Hispanic black children represent 39 percent of the high-dosage teacher training sample but only 51 percent of the matched control group. Results for the BPI internalizing scale suggest that children who received individual mental health consultation services have higher scores than their counterparts in the matched control groups (2.89 in the treated group vs. 2.19 in the matched control group). Nevertheless, the balance in these two variables improves considerably after matching. Matching is estimated to reduce the treatment-control difference by 22 percent for the variable that captures whether children are non-Hispanic black; it is found to decrease the difference by 10 percent for the variable that assesses the BPI internalizing scale score. In addition, treated and controlled classrooms do not show statistically significant differences in many covariates before matching. This is probably due to the low power of the small sample sizes of class-level data in detecting differences at conventional levels of statistical significance. The balance in most class-level covariates increases after matching. Therefore, the principal score matching approach employed in this study is generally able to identify comparable control groups for the low- and high-dosage treatment groups. The analyses within the matched samples might be able to reduce the selection biases on the observed covariates in estimates of the dosage effects of the CSRP intervention.

Dosage Effects of the CSRP Intervention

Table 2 presents a summary of the results on estimated CSRP dosage effects. It combines the estimates from the analyses of five data sets that are generated by multiple imputation. In terms of magnitudes and levels of statistical significance, the results are quite consistent and robust across the five data sets. For purposes of comparison, previous findings on CSRP’s ITT effects (Raver et al. 2009, forthcoming) are presented in the second column. To account for the hierarchical structure of the CSRP data, the ITT effects are estimated using hierarchical linear modeling (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). As the discussion mentions, children in these data are nested in classrooms and Head Start sites. In table 2, columns to the right of the ITT estimates present coefficients for low- and high-dosage teacher training, low- and high-dosage MHC class visits, and children who received individual mental health consultation services. To facilitate the comparison of the point estimates from different sets of analyses in table 2, the corresponding effect sizes of these estimates are presented in the discussion below (without being shown in table 2). An effect size (ES) is measured in units of its SD (i.e., the point estimate divided by SD), which also makes it possible to compare the estimated effects in this study with those in other studies.

Table 2.

Program Effects of CSRP Intervention on Children’S School Readiness

| ITT | Teacher Training

|

MHC Class Visits

|

MHC for Children | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Dosage | High Dosage | Low Dosage | High Dosage | |||

| Teacher-reported behavior problems: | ||||||

| BPI internalizing scale | −1.81** (.43) | −1.36** (.46) | −1.99** (.54) | −1.12** (.39) | −1.92** (.52) | −1.61** (.30) |

| BPI externalizing scale | −2.92* (.92) | −2.27* (.89) | −4.06** (.87) | −2.10** (.33) | −3.33** (.79) | −2.41** (.54) |

| Observer-reported social-emotional skills: | ||||||

| Attention and impulse control | .20* (.08) | .07 (.06) | .49** (.10) | .14** (.03) | .43** (.12) | .31** (.08) |

| Positive emotion | −.01 (.08) | −.02 (.07) | .40** (.09) | −.01 (.12) | .31** (.08) | .18* (.05) |

| Observer-rated cognitive development: | ||||||

| PPVT | 1.46* (.61) | 1.22** (.45) | 3.70** (.89) | 1.10+ (.63) | 2.59** (.55) | 2.37** (.70) |

| Early math skills | 2.21** (.52) | 1.75** (.42) | 3.74** (.74) | 1.37** (.30) | 2.78** (.80) | 2.15* (.96) |

Note.—CSRP = Chicago School Readiness Project; ITT = intention to treat; MHC = mental health consultant; BPI = Behavior Problem Index; PPVT = Pea-body Picture Vocabulary Test III. Standard errors are presented in parentheses. Results are combined from the estimates of five data sets generated by multiple imputation.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 2 suggests that, as previously hypothesized, several of the CSRP effects on school readiness are larger than the estimated ITT effects. Specifically, all of the estimated effects of high-dosage teacher training are greater than the corresponding effects estimated for ITT, and the effects of MHC class visits also are generally larger. The effects of low-dosage training levels are found to be smaller than estimated ITT effects or are not statistically significantly different from the ITT estimates. Moreover, as the discussion mentions, children who received individual mental health consultation services, which are an extra dose of the CSRP intervention in addition to teacher training and MHC class visits, are matched to their counterparts in the control group who had similar pretreatment characteristics. As shown in the last column of table 2, the estimated effects of individual mental health consultation services on school readiness measures are statistically significant.

In particular, the results from ITT analyses (table 2) suggest that most of the effects are statistically significant. Specifically, the ITT estimates suggest that the CSRP intervention is negatively and statistically significantly associated with scores on the two BPI scales (−1.81 on internalizing, corresponding to an ES of −.91 SDs; −2.92 on externalizing, ES = −.64 SDs). The ITT estimates also suggest that the CSRP intervention is positively and statistically significantly associated with scores on the attention and impulse control subscale (.20; ES = .37 SDs), the PPVT (1.46; ES = .33 SDs), and the early math skills measure (2.21; ES =.53 SDs). Table 2 further suggests that low-dosage teacher training, which accounts for 30–60 percent of the total training hours provided by the CSRP, has smaller estimated effects on children’s BPI internalizing (−1.36; ES = −.69 SDs) and externalizing (−2.27; ES = −.50 SD) behavior problems than those identified in the ITT estimates, but the training effects are found to be statistically significant. Low-dosage training is estimated to be positively and statistically significantly associated with scores on PPVT (1.22; ES = .27 SDs) and early math skills (1.75; ES = .42 SDs). Both of those estimates are smaller than the corresponding ITT results. The coefficients for the attention and impulse control subscale and for positive emotion, still smaller than those in the ITT results, are estimated to be statistically nonsignificant.

In contrast, high-dosage teacher training, which accounts for 87–100 percent of the CSRP’s total training hours, is found to have larger effects than those estimated for the ITT results on all six of the outcome variables. High-dosage training is estimated to be negatively and statistically significantly associated with scores on both BPI scales (−1.99 on internalizing, ES = −1.01 SDs; −4.06 on externalizing, ES = −.89 SDs). High-dosage training is estimated to be positively and statistically significantly associated with scores on the attention and impulse control subscale (.49; ES = .91 SDs), the PPVT (3.70; ES = .83 SDs), early math skills (3.74; ES = .90 SDs), and children’s positive emotion (.40; ES =.76 SDs); the intervention is not statistically significantly associated with the positive emotion subscale score in ITT estimates.

Similarly, the results in table 2 suggest that the effects of low-dosage MHC class visits, which represent a level of exposure that falls below the average hours of MHC visits received in the treatment group, are smaller than those identified in ITT estimates on scores for both BPI scales, the attention and impulse control subscale, and early math skills. Low-dosage MHC visits are estimated to be negatively and statistically significantly associated with both internalizing (−1.12) and externalizing (−2.10) scales. The MHC visits are estimated to be positively and marginally associated with PPVT scores.

High-dosage MHC class visits represent a level of exposure that exceeds the average hours received by the treatment group. On all indicators of school readiness, high-dosage MHC visits are found to have larger effects than those identified in ITT estimates, and all of the coefficients are statistically significant.

Furthermore, the results in the last column of table 2 show that the individual mental health consultation services are estimated to have statistically significant effects on all measures of children’s school readiness. Children in treatment-assigned classes who received individual mental health consultation services are estimated to have lower BPI scores and higher social-emotional and cognitive scores than their matched counterparts in the control group who have similar pretreatment characteristics.

The full regression-adjusted results from this study are presented in appendix table A1. These results are combined from the analyses of low- and high-dosage teacher training in the five imputed data sets. Although the magnitudes of associations and levels of statistical significance are estimated to be consistent and robust across the data sets, the standard errors are large, and most of the correlations are estimated to lose statistical significance when the results are combined. Analyses of the two CSRP components not shown in table A1 (MHC class visits and mental health consultation services for individual children) are found to produce very similar results. In addition, the authors also conducted dosage analyses that use the original data but do not employ imputation. The analyses identify patterns of dosage effects that are similar to the ones reported in this study, but the alternate analyses estimate smaller effects. Because missing data deprive these alternate analyses of statistical power, those results are also less likely to reach statistical significance.

Variations in Dosage Effects across Outcomes and CSRP Components

In addition, the results in table 2 also show the variations of dosage effects across school readiness measures and the CSRP intervention components. These estimates suggest that high-dosage teacher training is associated with larger reductions in children’s externalizing behavior problems than are found in the ITT estimates. The effects of high-dosage training on social-emotional skills (scores on subscales for attention and impulse control and for positive emotion) and cognitive development (scores on the PPVT and early math skills) are estimated to be larger than those derived from ITT analyses. The estimates further suggest that low-dosage teacher training is not statistically significantly associated with either measure of children’s social-emotional skills. Although statistically significant, the estimated effects of low-dosage training on internalizing behavior problems, externalizing behavior problems, PPVT scores, and early math skills are smaller than those derived from ITT analyses.

Similarly, low-dosage MHC class visits are estimated to predict smaller gains in children’s school readiness outcomes (the association between low-dosage visits and the positive emotion score is found to be statistically nonsignificant; such visits are only estimated to be marginally associated with PPVT scores) than those derived from the ITT analyses or found in the high-dosage treatment estimates. In contrast, high-dosage MHC class visits are estimated to be statistically significantly related to all measured outcomes. The effects on reducing children’s behavior problems, social-emotional skills, and cognitive development are all estimated to be larger than the effects derived from ITT estimates.

Moreover, results suggest that the individual mental health consultation services are especially efficient in promoting these children’s social-emotional and PPVT skills. The effects of individual mental health consultation services on attention and impulse control, positive emotion, and PPVT scores are estimated to be larger than those derived from ITT estimates. The effects of individual mental health consultation services for children on the other measures of school readiness are estimated to be slightly smaller than those found in ITT estimates, but receipt of individual services is estimated to be statistically significantly associated with all of those outcomes.

The results in table 2 also permit comparisons of the effects estimated for teacher training with those estimated for MHC class visits. Compared with the effects estimated for low-dosage MHC visits, those estimated for low-dosage teacher training are larger on all measured outcomes except the score for the attention and impulse control subscale. So, too, the effects of high-dosage teacher training are estimated to be larger on all measured outcomes than those for high-dosage MHC class visits. The estimated effect sizes of individual mental health consultation services for children tend to fall between those of the low- and high-dosage levels of the other two components (i.e., teacher training and MHC class visits).

Conclusion and Discussion

Variations in compliance with social interventions, and in such interventions’ effects on program outcomes, increasingly capture attention in the fields of policy evaluation and prevention science. Yet these important and policy-relevant empirical questions remain relatively understudied. This is due in part to the ways in which questions of dosage are complicated by the inferential challenges posed by individual differences in participants’ propensity to take up or enroll in services. Using a principal score matching method to address the issue of selection bias, the current study examines the dosage effects of the CSRP, a classroom-based intervention conducted in Head Start settings located within seven disadvantaged Chicago neighborhoods. The analyses suggest several different solutions to the challenges of estimating the role of dosage across multiple program components of service delivery, within a cluster-randomized early intervention program, and at both the classroom and the child levels of analysis.

Using a principal score matching approach, the study finds that high-dosage levels of teacher training (i.e., 87–100 percent of the CSRP’s total training hours) and high-dosage MHC class visits (i.e., above the average hours in the treatment group) are estimated to have larger effects on children’s school readiness than those derived from ITT analyses. In contrast, low-dosage levels of treatment (i.e., 30–60 percent of the total training hours for teacher training and below the average hours for MHC class visits) are predicted to have program effects that are smaller than those derived from ITT estimates or that are statistically nonsignificant. Moreover, individual mental health consultation services are estimated to be statistically significantly associated with the measured indicators of school readiness among children identified in a pretreatment assessment as having high levels of emotional and behavioral problems. In addition, dosage effects are found to vary across school readiness measures and the CSRP intervention components.

The findings in this study should be interpreted with caution. The CSRP intervention was conducted among a small sample of children who attended Head Start programs located in seven very disadvantaged neighborhoods in Chicago. The majority of the CSRP participants are reported to be either non-Hispanic black (66 percent) or Hispanic (26 percent). The sample thus did not share the ethnic composition of Head Start as a whole. In 2005 (the same time period as this evaluation), approximately 35 percent of enrolled Head Start participants were white, 31 percent were black, and 33 percent were Hispanic (Office of Head Start 2006). Moreover, research suggests that, across states and localities, there is considerable variation in preschool programs (Head Start and prekindergarten), the characteristics of enrolled children, and the effects of these programs on children’s developmental outcomes (Gormley 2007; Rigby, Ryan, and Brooks-Gunn 2007; Wong et al. 2008). In addition, the design of the CSRP intervention, which is conducted in Head Start program settings, might influence its treatment effects in ways that differ from the influences exerted in other preschool settings. Therefore, the study’s findings on the program effects of the CSRP intervention, including the estimates of ITT and dosage effects, should be understood to represent a specific context: a single efficacy trial in 18 Head Start programs in Chicago. As such, the results should not be generalized more broadly. To check the robustness of the findings in this study and to provide more generalizable results, future research should employ samples that are more demographically and geographically representative of the national population of preschool-aged, economically disadvantaged children. Such research should occur within the context of a large-scale intervention.

Results also suggest that the dosage measures for the three components of the CSRP intervention are relatively independent from each other. For this reason, the dosage effects of individual components are estimated under the assumption that the participants also received the services of other components, the dosage levels of which were distributed equally or randomly. For example, in comparing the outcomes of children in the low-dosage teacher training group with those of children in the control group who had similar background characteristics, one should keep in mind that children in the low-dosage teacher training group received MHC class visits as well, and some of them also received individual mental health consultation services. As the findings from ITT and individual dosage analyses suggest, all three components of the CSRP intervention could contribute to the promotion of children’s school readiness. The estimates of the respective roles of the study’s individual CSRP components might be larger than the estimates obtained if these individual components of services were provided separately as single packages of intervention to different groups of children. Nevertheless, due to the small sample size and the multifaceted design of the CSRP intervention, it was not possible to detect the pure effects of different dosage levels in individual program components. If fiscally and practically feasible, an important next empirical step would be for researchers to conduct efficacy trials in which individual components are unbundled and implemented separately for different groups of children. Such a design would help identify the components’ ITT as well as dosage effects.