Summary

We investigated the use of mid-treatment FDG-PET as an objective quantification of radiation esophagitis for NSCLC patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy. FDG-PET uptake was normalized to low-dose regions of the esophagus to create localized radiation response metrics. We found normalized PET uptake was highly correlated to esophagitis grade, both during the PET study, and by treatment completion. In addition, PET uptake can predict eventual esophagitis from patients who are asymptomatic during the mid-treatment PET scan.

Keywords: Esophagitis, FDG-PET, Normal Tissue Toxicity, NSCLC, Radiation Therapy

Introduction

Esophagitis is a wide class of disorders in the esophagus (1–3). Although there are many causes for the various types of esophagitis, one commonality is organ inflammation, which is detectable on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) studies (4–7). Acute radiation esophagitis is caused by radiotherapy for malignant thoracic tumors and occurs during treatment. Radiation esophagitis not only adversely affects patient quality of life, but also therapeutic efficacy by preventing tumor dose escalation and possibly causing treatment interruption (8,9). These negative effects on outcome are of great concern for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with severe radiation esophagitis occurring in approximately 25% of NSCLC patients receiving combined chemo-radiotherapy (10). Therefore, strategies to prevent esophagitis severity in NSCLC patients can have a large impact by improving outcome and quality of life.

Esophagitis severity is quantified with scoring systems such as Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events 3.0 (11). However, the scoring of esophagitis is subjective, based on the patient’s reporting of symptom severity and the physician’s prescribed treatment to manage symptoms. In addition, esophgeal infection or gastroesophageal reflux can produce radiation esophagitis-like symptoms, but may not be caused by radiotherapy. Furthermore, scoring systems like CTCAE are not able to identify the local affected region of the esophagus and must characterize the entire organ as having toxicity. For these reasons, it is prudent to employ objective quantifications of esophageal injury that give insight into the underlying physiological disorder, as well as the location of toxicity.

FDG-PET is a functional imaging technique that uses glucose metabolism as a surrogate for tissue inflammation, with many applications (12,13). Previous studies have shown normal tissue FDG-PET uptake is associated with radiation pneumonitis and esophagitis (14–20). However, no study has yet developed localized measures of FDG uptake, attempted to examine how the timing of esophagitis progression relates to mid-treatment FDG uptake, or investigated the ability of FDG uptake to detect or predict esophagitis symptom development, particularly to geometric regions of the esophagus. The use of FDG-PET to quantify esophagitis can potentially provide an objective quantification of esophagitis as a patient-specific esophageal response to radiation, and may localize the injured region of the esophagus.

The purpose of the current study was to investigate esophageal FDG uptake during radiation therapy as an objective and localized quantification of patient-specific tissue response to radiation and esophagitis symptoms, with the future goal of using these radiation-response metrics for dose-response studies. We also investigated the ability of normalized uptake to predict esophagitis progression in patients who were asymptomatic during the PET study.

Methods and Materials

Patient Population

Approval was obtained from the University of Texas-MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board to conduct the current study, with compliance to HIPAA regulations. We identified 79 patients for our retrospective analysis from a prospective clinical trial cohort with inoperable NSCLC. All patients in the clinical trial were treated with concurrent chemotherapy (paclitaxel and carboplatin) and either intensity-modulated photon radiation therapy or passive scatter proton radiation therapy, with a tumor prescription dose of 60–74 Gy in 2-Gy fractions over 6–8 weeks from 2008 to 2014. Treatment planning was conducted using Pinnacle software (Philips Healthcare, Bothwell, WA) for patients receiving photon therapy and Eclipse software (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA) for those receiving proton therapy. Esophagus contours were segmented in the axial plane from the cricoid cartilage to the gastroesophageal junction. Esophagitis was prospectively scored weekly throughout treatment using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events 3.0. Standard clinical practice at our institution is liquid narcotic medication, antacids, and/or topical anesthetics for grade 2 esophagitis. If symptoms become more severe, IV fluids for greater than 24 hours and/or feeding tube is prescribed, escalating esophagitis grade to 3. The 79 patients selected for our analysis underwent combined PET and computed tomography (CT) studies midway through treatment. The distribution of esophagitis grades was as follows: 43 grade 0, 30 grade 2, and 6 grade 3 at the time of the PET studies, and progressed to maximum esophagitis of 17 grade 0, 40 grade 2, and 22 grade 3, by treatment completion. For the 43 grade 0 patients at time of the PET study, 26 would progress to have esophagitis (23 grade 2, 3 grade 3).

PET/CT Studies

All PET/CT scans were acquired with a General Electric Discovery ST PET/CT scanner (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI) with 3.9×3.9×3.3mm3 voxels. PET/CT studies were conducted in the treatment position with standard patient immobilization used for planning CT scans. All PET studies were attenuation-corrected with an accompanying CT scan. PET scans were conducted at a median of 100.1 minutes (range, 58.1–159.2 minutes) after injection of a median of 377.0 MBq (range, 241.4–507.2 MBq) of FDG. The PET/CT scans were deformed using a B-splines image registration algorithm in the planning CT frame of reference and resampled into 0.98×0.98×2.50mm3 voxels using Velocity AI 3.0.1 (Velocity Medical Solutions, Atlanta, GA). The timing of the PET studies during treatment was not uniform. On average, the PET scan was acquired at fraction 23 (±2.4 standard deviation, 18–28 range).

Normalized FDG Radiation-Response

We developed in-house code for data extraction, uptake calculation, and analysis using MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA). This software converted the esophageal segmentation into a binary mask and aligned the frame of reference of both the PET image and the dose image, and then extracted corresponding voxel values of PET counts and radiation dose. FDG uptake was quantified as the standard uptake value (SUV) according to the bodyweight calculation, with voxel SUVMean and SUVMax calculated (12).

To control inter-patient FDG uptake variability, uptake was normalized as a patient-specific radiation response quantification. For each patient, we calculated a normalization factor of the mean SUV value for esophageal voxels irradiated up to a 5Gy threshold, for delivered dose at the time of the PET study, and then divided the remaining esophageal PET voxels by the normalization factor. The normalized SUV equation is:

| (1) |

Where SUVMean<5Gy is the average FDG uptake in the low-dose region of the esophagus and SUV(x,y,z)>5Gy is the voxel FDG uptake value. The normalized SUV (nSUV) represents the percent uptake increase from the low-dose esophageal region due to radiation dose. Normalization low-dose cutoff value was analyzed for threshold values of 1, 2, 5, 8, and 10-Gy.

Localized uptake metrics were derived by averaging nSUV at each axial segment of the esophagus in two ways: axial-averaged maximum nSUV for 1, 3, 5, and 7-slices (e.g., nSUVAxMax7 for the 7-slice average) and axial length of esophagus with at least a given percentage of axial-averaged nSUV response (e.g., nSUVLen40 for esophageal length with nSUV ≥ 40% axial-averaged response over the baseline SUVMean<5Gy value), with an nSUV increase ranging from 20% to 60% in 10% increments. Voxel nSUV mean (nSUVMean), maximum (nSUVMax), and percentile nSUV values from sixty-fifth to ninety-fifth percentile (e.g., nSUVPerc65 for the sixty-fifth percentile) were also calculated. Standard SUV values of SUVMax and SUVMean were also reported.

Esophagitis Timing and Progression

The relationship between esophagitis grade (both maximum grade and grade at the time of the PET study) and normalized uptake was examined. The timing of esophagitis severity and progression to maximum grade was analyzed in terms of treatment fractions between the PET scan and the escalation of grade, and then compared with nSUV.

The ability of mid-treatment nSUV to predict maximum esophagitis grade was also investigated for patients who were asymptomatic during the PET study. These patients were grouped as: grade 0 at the time of the PET study that remained grade 0 throughout treatment (G0-0), grade 0 that became grade 2 or 3 (G0-2/3), grade 2 that stayed grade 2 (G2-2), grade 2 that became grade 3 (G2-3), and grade 3 that stayed grade 3 (G3-3). Progression for G2-3 patients was not analyzed due to low sample size. No patients had esophagitis grade escalate after completion of radiation therapy. Prediction of symptom progression from asymptomatic patients during the PET study (n = 43) was created using logistic regression and nSUV metric values. Model construction is described in the following section.

Statistical Analysis

FDG uptake and dose metrics were compared with esophagitis grade, both at the time of the PET study and maximum treatment grade, for ≥grade 2 esophagitis complication using univariate logistic regression and Spearman rank analysis. Model fit was assessed using area under the curve (AUC) from receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis. Reported Logistic regression p-values were calculated using the likelihood ratio chi-square test. Prediction of maximum esophagitis grade from mid-treatment nSUV was tested using the Mann-Whitney U test. All p-values were reported after applying the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery procedure. P-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To test the relationship of nSUV and esophagitis grade in a multivariate analysis, least absolute shrinkage selection operator (LASSO) penalized logistic regression was utilized. LASSO has the ability to ignore redundant features and improve predictive ability when compared to stepwise logistic regression (21,22). Model features in the form of nSUV were used to predict ≥grade 2 esophagitis at time of PET study, and ≥grade 2 maximum treatment grade. A 3-fold cross-validation procedure (folds of 1 training, 1 validation, and 1 test) was repeated for 100 iterations, with AUC calculated from NTCP predictions (probability of ≥grade 2 esophagitis incidence) on the test fold for every iteration. The AUCMean and standard deviation of AUC values quantifies the robustness of the trained nSUV model to classify esophagitis on the test set. LASSO model parameters were derived from the validation set and the tested model was constructed from the training set.

To investigate the added value of nSUV in classifying esophagitis, dosimetric features were examined as separate model features and then repeated with nSUV features to predict ≥grade 2 esophagitis in the model construction method previously described. Dosimetric features were quantified using dose-volume histogram (DVH) metrics in the form of esophagus volume receiving at least X dose (VX), length of esophagus irradiated to at least X dose with complete esophageal axial coverage (LEX), and mean (MED) and max (DMax) esophageal dose. Dose metrics were also quantified and separately tested in model construction in the form of fractional DVH metrics, for each patient’s fraction at time of the PET study.

The previously described model construction method was implemented with asymptomatic patients at time of the PET study (N=43), to predict symptom progression by completion of treatment (≥grade 2). Model construction of nSUV-only, dose-only, and nSUV and dose features were conducted.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Clinical factors of the 79 patients studied are summarized in Table 1. No clinical factors were associated with esophagitis grade, either maximum grade or grade during the PET study. Neither injected FDG dose nor PET scan times were correlated to nSUV metrics. In addition, the timing of the PET study was not associated with esophagitis or nSUV metrics’ value.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the 79 study patients.

| Characteristic | Datum |

|---|---|

| Median age (range) | |

| All | 66 years (38–80 years) |

| Male | 65 years (51–79 years) |

| Female | 66 years (38–80 years) |

| Sex | |

| No. of Males | 46 |

| No. of Females | 33 |

| Histologic findings | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 31 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 41 |

| Large cell carcinoma | 3 |

| Other | 4 |

| Smoking history | |

| Current smoker | 27 |

| Former smoker | 46 |

| Never smoked | 6 |

| Stage | |

| IIa | 3 |

| IIb | 5 |

| IIIa | 29 |

| IIIb | 38 |

| IV | 4 |

| Treatment dose, Gy | |

| 74 | 46 |

| 66 | 28 |

| 60 | 5 |

Normalization

The normalization factor was calculated for threshold values of 1, 2, 5, 8, and 10 Gy for 50 of the 79 patients studied. The 5Gy threshold was selected. The average percent difference between using 5Gy normalization factor versus other examined threshold values was 2.36% (±2.00% standard deviation), with four patients more than 6.00% (10.48% maximum). In addition, nSUV metrics were calculated for these 50 patients and the effect of different threshold values was analyzed. None of the metrics had an average difference of more than 4.8% for an individual patient. Since effect of threshold choice was minimal, two patients had nSUV metrics calculated with different normalization factor thresholds (1Gy, 8Gy) to acquire an adequate amount of normalization voxels for analysis.

Normalized FDG Uptake and Esophagitis Severity

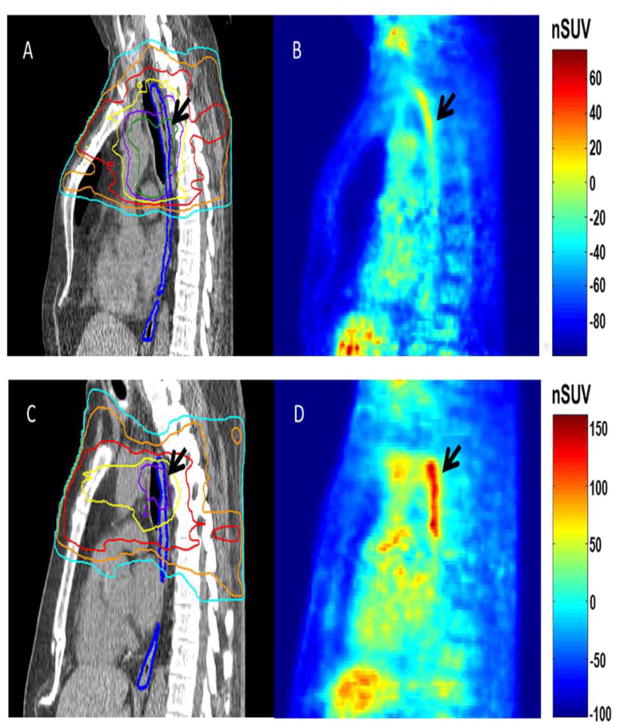

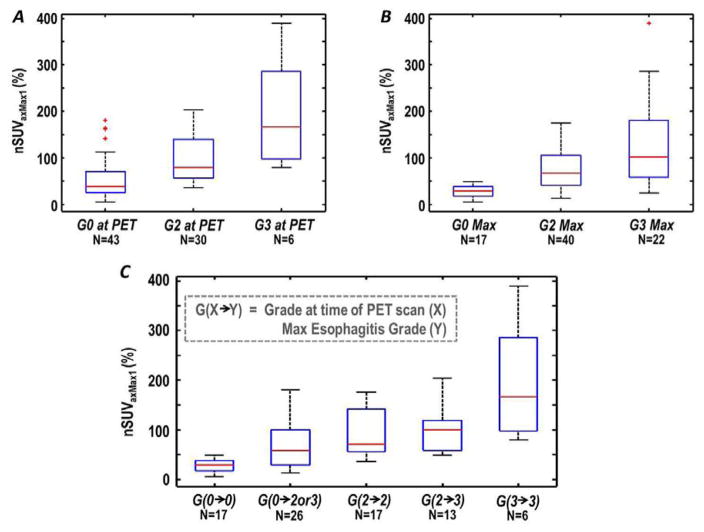

Normalized uptake generally increased along with esophagitis severity. This was true of both esophagitis grade measured during the PET study, and treatment maximum. For each patient, increased normalized uptake was confined to the region of highest radiation dose along the length of the esophagus (figure 1). The ability of nSUV to stratify patients on the basis of esophagitis grade at the time of the PET study, as well as the maximum esophagitis grade, is shown for nSUVAxMax1 in Figure 2 A,B. A strong trend of increasing nSUV with increasing esophagitis severity is observed. Grouping patients’ esophagitis grade during the PET study and the maximum grade showed a trend of increasing normalized uptake with increasing esophagitis severity (Figure 2C). Figure 2 shows the ability of nSUV to stratify esophagitis severity, as well as esophagitis progression, from the time of the PET study to treatment completion; for comparison, boxplots of the mean and maximum esophageal dose grouped according to esophagitis grade are presented in the supplemental materials.

Figure 1.

Sagittal view of esophageal anatomy as measured by computed tomography (CT; left panels) with radiation dose and normalized uptake in the sagittal plane (right panels) for an asymptomatic patient (68 year old male), A,B, and a patient (73 year old male) with grade 3 esophagitis at the time of the positron emission tomography (PET) stud, C,D. The esophagus is outlined in blue on the CT scans, with radiation planning isodose lines of 20 Gy (light blue), 30 Gy (orange), 40 Gy (red), 50 Gy (yellow), 60 Gy (purple), and 70 Gy (dark green). The region of high esophageal dose and corresponding normalized standard uptake value (nSUV) is highlighted with the black arrows.

Figure 2.

Axial-averaged maximum normalized standard uptake values for 1 slice (nSUVaxMax1) for patients with grade 0, 2, or 3 esophagitis at the time of the positron emission tomography (PET) study, A, grade 0, 2, or 3 maximum esophagitis grades, B, and nSUVAxMax1 grouped by patient progression of esophagitis grade at the time of the PET study to maximum grade, C. Boxplot corners represent 25th and 75th percentiles and middle line the median value. Outliers are denoted as ‘+’.

In the univariate analysis, most nSUV metrics were significantly correlated with esophagitis grade (p < 0.05) for the endpoints investigated (Table 2). The highest performing metrics for both endpoints were nSUVAxMax1 and nSUVLen40, with AUC values ≥0.85 for ≥grade 2 esophagitis at the time of the PET study and AUC values ≥0.91 for maximum esophagitis ≥grade 2. SUVMean was associated only with ≥grade 2 esophagitis at the time of the PET study. SUVMax was significantly correlated (p < 0.05) with both endpoints, but performance was much lower than any significant normalized uptake metric (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of the relationship between 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake metrics and esophagitis grade at the time of the FDG-positron emission tomography (PET) scan, and maximum treatment esophagitis grade (n = 79). Univariate logistic regression p-values reported have been corrected with the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate procedure.

| FDG uptake metric | ≥Grade 2 during PET scan | ≥Grade 2 Treatment Maximum | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| P Value | AUC* | P Value | AUC* | |

| SUVmean | 2.04E-02 | 0.67 | 2.35E-01 | 0.61 |

| SUVmax | 5.23E-03 | 0.73 | 1.88E-03 | 0.75 |

| nSUVmean† | 8.16E-05 | 0.84 | 4.09E-05 | 0.87 |

| nSUVmax | 1.55E-04 | 0.82 | 1.26E-06 | 0.91 |

| nSUVaxMax1‡ | 8.16E-05 | 0.85 | 1.17E-06 | 0.91 |

| nSUVaxMax3 | 5.32E-05 | 0.85 | 9.53E-06 | 0.87 |

| nSUVaxMax5 | 5.75E-05 | 0.84 | 1.52E-05 | 0.86 |

| nSUVaxMax7 | 8.16E-05 | 0.81 | 3.65E-05 | 0.84 |

| nSUVlen20** | 5.32E-05 | 0.80 | 7.37E-06 | 0.89 |

| nSUVlen30 | 5.32E-05 | 0.84 | 1.17E-06 | 0.91 |

| nSUVlen40 | 8.16E-05 | 0.85 | 6.52E-08 | 0.92 |

| nSUVlen50 | 7.15E-04 | 0.81 | 1.26E-06 | 0.87 |

| nSUVlen60 | 1.32E-02 | 0.74 | 4.23E-05 | 0.80 |

| nSUVperc65†† | 8.31E-05 | 0.83 | 1.12E-05 | 0.89 |

| nSUVperc75 | 8.31E-05 | 0.83 | 2.48E-06 | 0.90 |

| nSUVperc85 | 8.16E-05 | 0.84 | 2.48E-06 | 0.90 |

| nSUVperc95 | 4.69E-04 | 0.83 | 1.26E-06 | 0.91 |

Area under the curve.

Voxel mean normalized standard uptake value.

Axial-averaged maximum nSUV for 1, 3, 5, and 7 slices (e.g., nSUVaxMax1 for the 1-slice average).

Axial length of esophageal tissue with at least a given percentage of axial-averaged nSUV response (e.g., nSUVlen20 for a length of esophagus with nSUV ≥ 20% axial-averaged response over the baseline SUV value).

Voxel percentile nSUV values from the sixty-fifth to the ninety-fifth percentiles (e.g., nSUVperc65 for the sixty-fifth percentile).

The results of the multivariate analysis are listed in Table 3. Inclusion of only nSUV metrics for model features outperformed dose-only models for both ≥grade 2 esophagitis endpoint scenarios (AUC 0.83 and 0.88 vs. 0.52 and 0.76, for grade at time of PET scan and treatment completion, respectively). The difference in AUC between model types was significant for both grade at time of PET scan (p<0.05) and treatment completion (p<0.001), respectively. Models that combined nSUV and dose metrics showed slight improvement in AUC, albeit with higher model complexity. In addition, nSUV metrics had higher model occurrence and lower penalization on average than dose metrics.

Table 3.

LASSO regression multivariate analysis of nSUV metrics and ≥esophagitis grade 2 (N=79), and the symptom progression prediction model construction from grade 0 esophagitis patients at time of the PET study (N=43) Using 3-fold cross-validation repeated for 100 iterations. The median model order, mean AUC value with standard deviation, and the most prevelant recurring model features in the cross-validation process are listed.

| Feature Class | Endpoint | Model Order | AUCmean* (S.D.) | Top Recurring Occurrence† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nSUV** | Mid-treatment ≥Grade 2 | 5 | 0.83 (±0.07) | nSUVMean, nSUVLen30, nSUVAxMax3, nSUVLen20, nSUVAxMax1 |

| Treatment Max ≥Grade 2 | 4 | 0.88 (±0.05) | nSUVLen40, nSUVMean, nSUVLen30, nSUVAxMax1 | |

| DVH†† | Mid-treatment ≥Grade 2 | 3 | 0.52 (±0.07) | LE10100%, LE50100%, MED |

| Treatment Max ≥Grade 2 | 3 | 0.76 (±0.12) | Dmax, LE40100%, V50 | |

| nSUV** & DVH†† | Mid-treatment ≥Grade 2 | 6 | 0.81 (±0.07) | nSUVMean, nSUVAxMax5, nSUVLen40, LE50100%, nSUVAxMax1 |

| Treatment Max ≥Grade 2 | 5 | 0.91 (±0.06) | nSUVMean, LE50100%, nSUVLen40, LE30100%, nSUVLen30 | |

| DVH†† | Symptom Progression ≥Grade 2 | 3 | 0.67 (±0.13) | Dmax, V30, LE30100% |

| nSUV** | 3 | 0.75 (±0.10) | nSUVLen30, nSUVLen40, nSUVAxMax1 | |

| nSUV** & DVH†† | 4 | 0.72 (±0.12) | nSUVLen30, nSUVLen40, nSUVAxMax1, LE40100% |

Mean area under the curve from repeated cross-validation.

Dose and normalized uptake abbreviations defined in the methods section.

Normalized FDG uptake

Dose-volume histogram

Normalized Uptake and Esophagitis Timing

On average, symptoms were clinically reported after nSUV quantification. For all 26 asymptomatic patients during the PET study that would develop ≥grade 2 esophagitis by treatment end (G0-2/3), esophagitis occurred a median of 6 fractions after the PET scan. For patients who had grade 2 esophagitis during the PET scan that became grade 3 esophagitis by the end of the treatment, the median time to onset was 7 fractions.

Normalized Uptake to Predict Esophagitis Progression

Figure 1C shows the difference in nSUV for the 2 asymptomatic patient groups during the PET study. Patients who eventually developed grade ≥2 esophagitis had markedly higher nSUV values during the PET study than those who did not develop esophagitis. The Mann-Whitney U test showed differences in nSUV metric distributions between these 2 groups were significantly different (p < 0.05) for all nSUV metrics examined; differences in SUVMax or SUVMean were not significant. The performance of symptom progression models was AUCMean = 0.67 and 0.75 for the dosimetric and nSUV-based models, respectively (Table 3). The combined features of dose and nSUV did not improve model AUCMean over nSUV-only models (0.72). The top recurring features were: nSUVLen30, nSUVLen40, and nSUVAxMax1 in both model types.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that FDG uptake can be used as an objective quantification of esophagitis during radiation therapy for NSCLC, and to predict symptom progression for asymptomatic patients at the time of the PET study. Our goal was to develop an in-vivo method of quantifying esophagitis that provides spatial information about the specific location and extent of injury. We accomplished this by deriving localized metrics of normalized uptake from PET studies performed during radiation treatment and establishing the relationship between these metrics and esophagitis grade.

Previous studies have shown that FDG uptake can quantify normal tissue response in lung for patients with NSCLC and esophageal cancer (15–20)]. Nijkamp et al also examined the use of posttreatment FDG-PET studies to quantify esophageal injury from radiation therapy (23). Lyman-Kutcher-Burman models were created with and without FDG uptake to predict esophageal injury, and these models showed that prediction was improved by adding PET information to the dose-response model (24). Another study showed an increase in FDG uptake at 6 discrete points along the length of the esophagus, with uptake normalized to the aortic arch (25). In another study, Mehmood et al showed the change in the 95th percentile of SUV of the esophagus from pre-treatment to weeks 2,4, and 7 of chemoradiotherapy is correlated to esophagitis using rigid PET image alignment, for 27 patients (26). However, these previous studies did not describe uptake in terms of esophagus geometry or conduct prediction modeling for symptom progression. In addition, various metrics with localization of response were not derived and tested in a multivariate analysis.

FDG uptake was normalized to the < 5Gy region of irradiated esophagus to reduce inter-patient variability of SUV. Standard SUVMean and SUVMax were not able to stratify or predict the progression of esophagitis. The choice of normalization has been utilized in studies of radiation-induced lung toxicity using FDG-PET (15–20). Another study used change in FDG-PET SUV during radiation therapy relative to pre-treatment status (26). Since pre-treatment PET studies acquired in the treatment position were not available for our patient cohort, this normalization method was not feasible.

Normalized uptake metrics performed well in classifying not only esophagitis grade at the time of the PET scan, but also maximum esophagitis grade. Combining multiple nSUV metrics in logistic regression models to classify esophagitis did not substantially improve AUC value over using a single nSUV metric (Table 3). DVH metrics alone performed poorly in classifying esophagitis grade. When DVH metrics were combined with nSUV metrics, AUC improved slightly for only the ≥grade 2 treatment maximum endpoint (Table 3). In addition, nSUV metrics were chosen with higher frequency than DVH metrics in the nSUV/Dose-combined model construction. This shows the robustness of a single nSUV metric to quantify esophagitis.

In addition to classifying esophagitis, the normalized uptake has the ability to predict symptom progression from patients that have grade 0 esophagitis at the time of the PET study. The ability of the LASSO models to predict if a patient will become ≥grade 2 esophagitis by treatment completion was greater for nSUV-only models than DVH-only models, or the combined nSUV and DVH metric models, as quantified by the cross-validated AUCMean. The combined nSUV and DVH metric models outperformed the DVH-only models, with nSUV metrics chosen with higher frequency. The cross-validated AUCMean of 0.75 could potentially be improved with a larger sample size and increase standardization of CT/PET scan acquisition and processing. In the realm of radiation oncology, this may help reduce adverse effects from therapy, thereby improving patient quality of life and preventing costly interventions (e.g., feeding tube, hospitalization). In addition, the comparison of nSUV and DVH models shows normalized uptake is providing unique response information we cannot obtain from the DVH.

The timing of esophagitis symptoms and normalized uptake magnitude showed that increased uptake occurs before presentation of clinical symptoms. This supports the use of FDG uptake as a preemptive diagnostic tool for esophagitis development. Although the current study was conducted in patients with radiation-induced esophagitis, it may be possible to extend this methodology to other types of esophagitis.

Previously, our group established that esophageal swelling on CT scans is a robust, objective measure of radiation esophagitis (27,28). Interestingly, the highest performing CT-based measures of esophagitis were based on axial maximum expansion and esophageal length with expansion greater than 30%, which is consistent with our results with nSUV metrics (28). The performance of normalized uptake and esophageal expansion metrics most correlated to the ≥grade 2 treatment maximum esophagitis endpoint were similar with AUC values above 0.90. One difference in these two studies was the metric sampling frequency; weekly for expansion and once during treatment for normalized uptake. Normalized uptake’s classification performance could potentially be increased by sampling multiple times during treatment. Because swelling is an inflammatory response, it is feasible that this method could be applied to other forms of esophagitis for detection and quantification of injury.

Our study had limitations. Because only 1 PET scan was acquired during radiation treatment, the change of normalized uptake throughout treatment, including normalization value, could not be quantified for individual patients. Therefore, it is uncertain how early in radiation treatment quantification of esophagitis may be achievable using FDG uptake. However, several symptomatic patients did have large responses at fraction 18 (36 Gy prescription dose). In addition, specification of normalized uptake magnitude and the onset of symptoms were skewed for patients who already had esophagitis symptoms at the time of the PET study. Another limitation is the frequency of esophagitis scoring. Esophagitis was scored at the weekly radiation oncology symptom clinic, which introduces uncertainty when trying to establish time differences between uptake magnitude and esophagitis severity. In addition, esophagitis scoring is a subjective process and other endpoints may be examined as well (e.g. weight loss, patient reported outcomes, etc).

In conclusion, FDG-PET can be used to quantify esophagitis during radiation therapy. This quantification is noninvasive and objective, and also provides spatial information about the location and extent of esophageal injury which may be useful for studying esophageal dose-response, specifically with the inclusion of spatial information. Normalized uptake is a patient-specific radiation response that can predict whether patients who are asymptomatic at the time of the PET study may develop symptoms by the end of radiation treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Partial support from UT MD Anderson Cancer Center startup funds and National Institutes of Health Grant U19 2U19CA021239

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

No authors have any conflicts of interest associated with this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Levine MS. Radiology of Esophagitis: A pattern approach. Radiology. 1991;179(1):1–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.179.1.2006257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley J, Movsas B. Radiation esophagitis: Predictive factors and preventive strategies. Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 2004;14:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galmiche JP, Zerbib F, des Varannes SB. Treatment of GORD: Three decades of progress and disappointments. United European Gastroenterology Journal. 2013;1(3):140–50. doi: 10.1177/2050640613484021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bural GG, Kumar R, Mavi A, Alavi A. Reflux esophagitis secondary to chemotherapy detected by serial FDG-PET. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2005;30(3):182–183. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200503000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhargava P, Reich P, Alavi A, Zhuang H. Radiation-induced esophagitis on FDG PET imaging. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2003;28(10):849–50. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000090936.30974.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakheet SM, Powe J. Benign causes of 18-FDG uptake on whole body imaging. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine. 1998;28(4):352–8. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(98)80038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isik A, Uras I, Uyar ME, Karakurt F, Kaftan O. Alendronate-induced Esophagitis. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2009;43(3):547–548. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruner DW, Movsas B, Konski A, et al. Outcomes research in cancer clinical trial cooperative groups: the RTOG model. Quality of Life Research. 2004;13(6):1025–1041. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000031335.02254.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox JD, Pajak TF, Asbell S, et al. Interruptions of high-dose radiation therapy decrease long-term survival of favorable patients with unresectable non-small cell carcinoma of the lung: analysis of 1244 cases from 3 raditation therapy oncology group (RTOG) trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;3(27):493–498. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werner-Wasik M, Yorke E, Deasy J, Nam J, Marks LB. Radiation dose-volume effects in the esophagus. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(3 Suppl):S86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.05.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trotti A, et al. CTCAE v3.0: Development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:176–181. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohren EM, Turkington TG, Coleman RE. Clinical applications of PET in oncology. Radiology. 2004;231(2):305–332. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2312021185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blodgett TM, Meltzer CC, Townsend DW. PET/CT: form and function. Radiology. 2007;242(2):360–385. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2422051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie L, Saynak M, Veeramachaneni NK, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer: prognostic importance of positive FDG PET findings in the mediastinum for patients with N0-N1 disease at pathologic analysis. Radiology. 2011;261(1):226–234. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guerrero T, Johnson V, Hart J, et al. Radiation pneumonitis: local dose versus [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake response in irradiated lung. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68(4):1030–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Ruysscher D, Houben A, Aerts H, et al. Increased (18)F-deoxyglucose uptake in the lung during the first weeks of radiotherapy is correlated with subsequent Radiation-Induced Lung Toxicity (RILT): a prospective pilot study. Radiother Oncol. 2009;91(3):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hart JP, McCurdy MR, Ezhil M, et al. Radiation pneumonitis: correlation of toxicity with pulmonary metabolic radiation response. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71(4):967–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mac Manus MP, Ding Z, Hogg A, et al. Association between pulmonary uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose detected by positron emission tomography scanning after radiation therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer and radiation pneumonitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80(5):1365–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCurdy MR, Castillo R, Martinez J, et al. [18F]-FDG uptake dose-response correlates with radiation pneumonitis in lung cancer patients. Radiother Oncol. 2012;104(1):52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Echeverria AE, McCurdy M, Castillo R, et al. Proton therapy radiation pneumonitis local dose-response in esophagus cancer patients. RadiotherOncol. 2013;106(1):124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference and prediction. 2. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu C, van der Schaaf A, Schilstra C, Langendijk J, van’t Veld A. Impact of Statistical Learning Methods on the Predictive Power of Multivariate Normal Tissue Complication Probability Models. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(4):677–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nijkamp J, Rossi M, Lebesque J, et al. Relating acute esophagitis to radiotherapy dose using FDG-PET in concurrent chemo-radiotherapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2013;106(1):118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burman C, Kutcher GJ, Emami B, Goitein M. Fitting of normal tissue tolerance data to an analytic function. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21(1):123–135. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90172-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan S, Brown R, Zhao L, et al. Timing and intensity of changes in FDG uptake with symptomatic esophagitis during radiotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy. Radiation Oncology. 2014;9(1):37. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-9-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehmood Q, Sun A, Becker N, Higgins J, Marshall A, Le LW, … Bissonnette J-P. Predicting Radiation Esophagitis Using 18F-FDG PET During Chemoradiotherapy for Locally Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2016;11(2):213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Court LE, Tucker SL, Gomez D, et al. A technique to use CT images for in vivo detection and quantification of the spatial distribution of radiation-induced esophagitis. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2013;14(3):4195. doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v14i3.4195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niedzielski JS, Yang J, Stingo F, et al. Objectively quantifying radiation esophagitis with novel computed tomography-based metrics. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;94(2):385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.