Abstract

Conventional anatomic imaging with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has limitations in the evaluation of prostate cancer. Positron emission tomography (PET) is a powerful imaging technique which can be directed toward molecular targets as diverse as glucose metabolism, density of prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) receptors, and skeletal osteoblastic activity.

While 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET is the mainstay of molecular imaging, FDG has limitations in typically indolent prostate cancer. Yet, there are many useful and emerging PET tracers beyond FDG which provide added value. These include radiotracers interrogating prostate cancer via molecular mechanisms related to the biology of choline, acetate, amino acids, bombesin, dihydrotestosterone, among others.

Choline is utilized for cell membrane synthesis and its metabolism is upregulated in prostate cancer. 11C-choline and 18F-choline are in wide clinical use outside the United States, and have proven most beneficial for detection of recurrent prostate cancer. 11C-acetate is an indirect biomarker of fatty acid synthesis which is also upregulated in prostate cancer. Imaging of prostate cancer with 11C-acetate is overall similar to the choline radiotracers yet is not as widely utilized.

Upregulation of amino acid transport in prostate cancer provides the biologic basis for amino acid based radiotracers. Most recent progress has been made with the non-natural alicyclic amino acid analogue radiotracer anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (FACBC or fluciclovine) also proven most useful for the detection of recurrent prostate cancer. Other emerging PET radiotracers for prostate cancer include the bombesin group directed to the gastrin releasing peptide receptor (GRPR), 16β-18F-fluoro-5α-dihydrotestosterone (FDHT) which binds to the androgen receptor, and those targeting the vasoactive intestinal polypeptide receptor 1 (VPAC-1) and urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) which are also overexpressed in prostate cancer.

Choline

Choline is a substrate for the synthesis of phosphatidyl-choline, which is the major phospholipid in the cell membrane. The uptake of choline is mediated by a specific transporter, upregulated along with choline kinase activity in tumor cells.1 The physiological uptake of 11C-choline includes salivary glands, liver, kidneys parenchyma and pancreas and faint uptake in spleen, bone marrow and muscles. Bowel and bladder activity can occasionally be observed. 11C has a half-life of 20 minutes, so it must be used rapidly after production. To overcome the drawback of short half-life of 11C, an 18F-labelled choline tracer (18F-fluorocholine or FCH) was developed as an alternative. The main difference between 11C-choline and 18F-choline is the earlier urinary appearance of the 18F probably due to incomplete tubular re-absorption.2 This aspect can affect the tracer performance for local relapse detection.

Primary disease

Early detection of prostate carcinoma is important since cancer confined to the prostate gland is often curable. However, the ability to image localized prostate carcinoma remains limited. When prostate carcinoma is suspected based on high prostate specific antigen (PSA) or abnormal digital rectal examination, the diagnosis typically relies on blind, systemic biopsies obtained under ultrasound guidance. Ultrasound has limited sensitivity. MRI is the best available imaging technique for identifying prostate carcinoma but is generally nonspecific for cancer, with abnormal signal being associated with prostatitis, scarring, or hyperplasia. Multi-parametric MRI (MP-MRI) has become popular but remains imperfect with sensitivities/specificities ranging from 22 85% to 50 99% depending on technical factors and the composition of the study population.3

At the present time, PET/CT with choline has limited value in assessing T status, and it has probably no role in assessing extra-capsular extension of the disease. Testa et al retrospectively reviewed MR imaging, 3D MR spectroscopy, and 11C-choline PET/CT in 26 men with biopsy-proved prostate cancer who underwent radical prostatectomy. Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were, respectively, 55%, 86%, and 67% with PET/CT; 54%, 75%, and 61% with MR imaging; and 81%, 67%, and 76% with 3D MR spectroscopy. The highest sensitivity was obtained when either 3D MR spectroscopic or MR imaging results were positive (88%) at the expense of specificity (53%), while the highest specificity was obtained when results with both techniques were positive (90%) at the expense of sensitivity (48%). Concordance between 3D MR spectroscopic and PET/CT findings was low (k=0.139).4

To further evaluate the potential usefulness of 11C-choline PET/CT for detection and localization of tumors within the prostate, Farsad et al studied 11C-choline PET/CT scans of 36 patients with prostate cancer and of 5 control subjects with bladder cancer, in comparison to histopathology on a sextant by sextant analysis. The sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of PET/CT were 66%, 81%, 71%, 87%, and 55%, respectively. This study demonstrated that 11C-choline PET/CT has a relative high rate of false-negative results on a sextant basis and that prostatic disorders other than cancer may accumulate 11C-choline. Therefore, the routine use of PET/CT with 11C-choline for intraprostatic tumor identification is not justified.5

Staging

Metastatic lymph nodal spread occurs in about 20–35% of patients with high risk histology according to nomograms, based on PSA level, age, Gleason score, and T status.6 The 5-years disease-free survival rate decreases from 85% for pN0 patients to 50% for pN1 patients.7 European guidelines on prostate cancers do not suggest any imaging method to stage the disease due to the lack of accuracy inherent with CT or MR in the detection of lymph nodal metastasis and that in low risk patients the probability of lymph nodal metastasis is lower than 10%, while in high risk patients the only recommended procedure is the extended pelvic lymph node dissection (ePLND).8

The three largest studies on PET/CT with choline (either 18F or 11C choline) for nodal staging demonstrate that choline PET/CT has an acceptable specificity and a low sensitivity. In 2008, Schiavina et al studied 11C-choline PET/CT in fifty-seven patients with intermediate and high-risk prostate cancer using histology as reference after ePLND.9 On a patient basis, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy were 60%, 97%, 90%, 87%, and 87%, respectively; on a lymph node basis these values were 41%, 99%, 94%, 97%, and 97%, respectively. Beheshti et al evaluated 18F-choline PET/CT in 111 patients, who subsequently underwent radical prostatectomy with ePLND.10 On a patient basis, PET/CT showed a sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of 66%, 96%, 82%, and 92%, respectively; on a lymph-node basis PET/CT showed a sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of 45%, 96%, 82%, and 83%, respectively. Moreover early bone metastasis were detected in two patients exclusively by PET/CT. Overall PET/CT led to a change in therapy in 15% of all patients and 20% of high-risk patients. Poulsen et al confirmed these data in a study performed on 210 patients with intermediate and high risk prostate cancer. Sensitivity of 73% and 56% was observed on a patient and lymph node basis, respectively, with a specificity of 87% and 94%.11

In summary, the use of choline PET/CT, labelled with either 11C or 18F, for preoperative lymph nodal staging showed relatively good specificity and poor sensitivity. The use of choline PET/CT as a whole body staging procedure in patients who are high risk for lymph nodal positive status (according to nomograms) may thus be worthwhile, since restricting choline imaging to this group with higher disease prevalence would reduce the number of negative or inconclusive choline PET/CT performed. More prospective studies are needed in order to determine cost-effectiveness and the impact of choline PET/CT in this cohort.

Recurrence

Monitoring PSA serum level is the best way to detect early disease recurrence after primary treatment. In the event of biochemical relapse, absolute PSA value and kinetics may be used as an imperfect indicator of the site of recurrence (local vs distal).12 The European Guidelines on prostate cancer do not suggest, in fact, any imaging procedure if PSA is lower than 20 ng/mL, since the accuracy of TRUS, CT, MR and bone scan is limited, particularly in patients with low PSA values.8 Despite these general recommendations, advanced imaging can be exploited to detect recurrence in order to establish the most appropriate therapy (systemic vs targeted). In particular PET imaging is of great interest since it can provide an evaluation of lymph node spread as well as bone metastasis in a single exam.

The first large prospective study of 11C-choline was performed by Picchio et al comparing 11C-choline PET with 18F-FDG PET in 100 prostate cancer patients with biochemical recurrence (mean PSA value 6.57 ng/mL). 11C-choline PET detected areas of abnormal uptake in 47% of patients, 27% with 18F-FDG PET.13 None of the FDG PET positive patients were choline PET negative, confirming that choline is significantly more sensitive than FDG in prostate cancer. Comparable results were reported by Richter at al who evaluated a cohort of seventy-three patients with median PSA of 2.7 ng/ml after radical treatment. The sensitivity of 11C-choline and FDG was 60.6% and 31%, respectively. In PSA levels over 1.9 ng/ml, sensitivity of 11C-choline and FDG increased to 80% and 40%, respectively. In the group receiving adjuvant hormone therapy, the diagnostic yields were 71.2% for 11C-choline and 43% for FDG. Interestingly, while 11C-choline PET could not differentiate well and poorly differentiated Gleason score patients, FDG-PET results were nearly significant (p = 0.058) highlighting that FDG could provide a prognostic index in prostate cancer patients.14

A prominent issue regards the relationship between 11C-choline detection rate and PSA level. To clarify this point, Krause et al evaluated sixty-three prostate cancer patients with biochemical relapse (mean PSA 5.9 ng/mL) after primary treatment by 11C-choline PET/CT.15 They demonstrated a significant correlation between PET/CT detection rate and PSA serum levels and showed an overall detection rate of 59% for 11C-choline PET/CT. In 358 prostate cancer patients (mean PSA 3.7ng/mL), Giovacchini et al found that on multivariate analysis, PSA levels, advanced pathological stage, previous biochemical failure and older age (> 65 years) were significantly (p<0.05) associated with an increased likelihood of positive 11C-choline PET/CT findings.16 In their retrospective review of 176 patients undergoing 11C-choline PET/CT for biochemical recurrence, Mitchell et al reported that the optimal PSA level for lesion detection was 2.0 ng/ml.17

Despite the recommendation to perform 11C-choline PET with an absolute PSA only greater than or equal to 2 ng/mL in order to maximize detection rate, PSA kinetics is another important factor that may influence study performance.8 Castellucci et al investigated the relationship between 11C-choline PET/CT detection rate and PSA kinetics (PSA velocity and PSA doubling time).18 They enrolled a total of 190 patients after radical prostatectomy who had an increased PSA (mean 4.2 ng/mL; median 2.1 ng/mL; range 0.2 25.4 ng/mL). They found that PSA doubling time (PSAdt) and PSA velocity (PSAvel) values were statistically different in patients with PET-positive and PET-negative findings. The authors concluded that PSA kinetics should be taken into consideration before performing a 11C-choline PET/CT in patients with biochemical failure because of its relevance to study positivity. Confirmatory results were published by the same group, who evaluated 102 patients previously treated with radical prostatectomy and presenting with a mild increase of PSA serum levels < 1.5 ng/mL (mean 0.86 +/− 0.40 ng/mL).19 Overall, 11C-choline PET/CT showed positive findings in 29/102 patients (28%). Using a retrospective cut off value for PSAdt of 7.25 months, there were only 2/56 (3%) positive 11C-choline PET/CT in patients with a PSAdt higher than the cut off, while 27/46 (58%) positive 11C-choline PET/CT in patients with a faster PSAdt (p < 0.001).

Delving deeper into the PSA kinetics choline detection rate issue, Giovacchini et al compared PSAvel and PSAdt to predict 11C choline PET/CT findings.20 PSAvel and PSAdt were retrospectively calculated in 170 prostate cancer patients with biochemical failure after radical prostatectomy, who underwent 11C-choline PET/CT for restaging of disease. Patients with positive 11C-choline PET/CT (n = 75) had significantly higher PSAvel than patients with negative 11C-choline PET/CT (n = 95). The percent of patients with positive 11C-choline PET/CT was 21% for PSAvel <1 ng/mL/y, 56% for PSAvel between 1 and 2 ng/mL/y, and 76% for PSAvel >2 ng/mL/y. The authors concluded PSAdt had greater statistical power compared with PSAvel, but that PSAvel can also be used to stratify the risk of positive 11C-choline PET/CT in prostate cancer patients with biochemical failure. They recommended that patients with PSAvel >1 ng/mL/y should be selected to increase the positive detection rate of 11C-choline PET/CT.

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is a systemic treatment that is often used in relapsed patients.8 Since ADT influences tumor progression, there was general concern about its possible influence on 11C-choline PET/CT detection rate. Fuccio et al investigated this issue by means of sequential 11C-choline PET/CT in 14 patients with recurrent prostate cancer during follow-up after radical prostatectomy with rising PSA levels.21 All patients had undergone at least two consecutive 11C-choline PET/CT scans before and 6 months after ADT administration. The mean serum PSA level before ADT was 17.0 ± 44.1 ng/ml. After 6 months of ADT administration the PSA value significantly decreased in comparison to baseline (PSA = 2.4 ± 3.1 ng/ml, p < .025). Moreover, before starting ADT, 13 of 14 patients had positive 11C-choline PET/CT for metastatic spread, while after 6 months of ADT administration 11C-choline PET/CT became negative in 9 of 14 patients. These preliminary results suggested that ADT significantly reduces 11C-choline uptake in androgen-sensitive prostate cancer patients. Similar results were published by Ceci et al who retrospectively evaluated 10 patients after radical prostatectomy (n = 8) or external beam radiotherapy (n = 2) as primary therapy, studied with sequential 11C-choline PET/CT.22 The first PET/CT (PET1) was performed during androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and the second PET/CT (PET2) was performed after therapy interruption. Only patients with negative results at PET1 were included in the study. At the time of PET1, all patients had received ADT for at least 6 months (mean PSA 0.54 ng/mL). At the time of PET2, all patients had completed ADT for a mean period of 7 months. 11C-choline PET/CT findings were validated by a follow-up of at least 12 months or histological confirmation in case of local relapse. PET2 has been able to detect the site of recurrences in all cases.

Another emerging application of 11C-choline PET/CT includes the possibility to monitor treatment response in castration resistant patients, when the serum PSA level may become uncoupled from viable tumor burden. Ceci et al analyzed 61 patients who performed 11C-choline PET/CT at baseline (PET1) and after docetaxel treatment (PET2).23 PSA values were measured before and after treatment. 40 (65.5 %) patients showed progressive disease, 13 (21.3 %) stable disease, 2 (3.4 %) showed partial response, and 6 (9.8 %) complete response. An increasing PSA trend was seen in 29 patients (47.5 %) and a decreasing PSA trend in 32 patients (52.5 %). In the multivariate statistical analysis, the presence of more than ten bone lesions detected on PET1 was significantly associated with an increased probability of progressive disease on PET2. No association was observed between PSA level and progressive disease on PET2. These results suggest that an increasing PSA trend measured after docetaxel treatment could be considered predictive of progressive disease but in patients with decreasing PSA values, 11C-choline PET/CT may be useful to identify those with progression despite a PSA response.

Choline PET/CT can have a significant impact on patient management. To prove this, Ceci et al analyzed data collected on 150 patients from two centers (Bologna and Würzburg) with biochemical relapse after radical therapy.24 The intended treatment before PET/CT was salvage radiotherapy of the prostate bed in 95 patients and palliative ADT in 55 patients. Changes in therapy after 11C-choline PET/CT were implemented in 70 of the 150 patients (46.7%). 11C-choline PET/CT was positive in 109 patients (72.7%) detecting local relapse (prostate bed and/or iliac lymph nodes and/or pararectal lymph nodes) in 64 patients (42.7%). Distant relapse (retroperitoneal lymph nodes and/or bone lesions) was seen in 31 patients (20.7%), and both local and distant relapse in 14 (9.3%). PSA level, PSA doubling time and ongoing ADT were significant predictors of a positive scan (p < 0.05). 11C-choline PET/CT was therefore proved to have a significant impact on therapeutic management in this setting although further prospective studies are needed to evaluate the effect of such treatment changes on patient survival.

Recent work has also been published comparing the detection of recurrent prostate cancer with 11C-choline PET/CT to that of MP-MR.25 In a 115 retrospective, single-institution study of post-prostatectomy subjects, Kitajima et al reported patient level receiver-operating characteristics (area under curves) of MP-MR imaging compared to 11C-choline PET/CT for local recurrence, pelvic locoregional nodal spread, and skeletal metastases to be 0.909 versus 0.761 (P<0.01), 0.812 versus 0.952 (P<0.01), and 0.927 versus 0.898 (not significant), respectively. This study suggests potential utility of novel technology such as PET-MR utilizing advanced PET radiotracers such as choline for prostate cancer.

In summary, choline PET/CT is not indicated for primary prostate cancer detection nor routine staging. However it has played an important role in the detection of locoregional lymph node and distant recurrence in patients with biochemical recurrence, significantly impacting patient management. In particular, choline PET/CT may be useful as the first diagnostic procedure in patients who demonstrate significantly elevated PSA and/or fast PSA kinetics. In patients with low PSA and/or slow PSA kinetics, the sensitivity of choline PET/CT is limited. Emerging applications include use for therapy assessment, especially in castration resistant patients when the PSA value is not predictive for disease burden. 11C-Choline has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for imaging of patients with suspected prostate cancer recurrence and non-informative bone scan, CT, or MRI. Figures 1 and 2 are examples of choline imaging in prostate cancer.

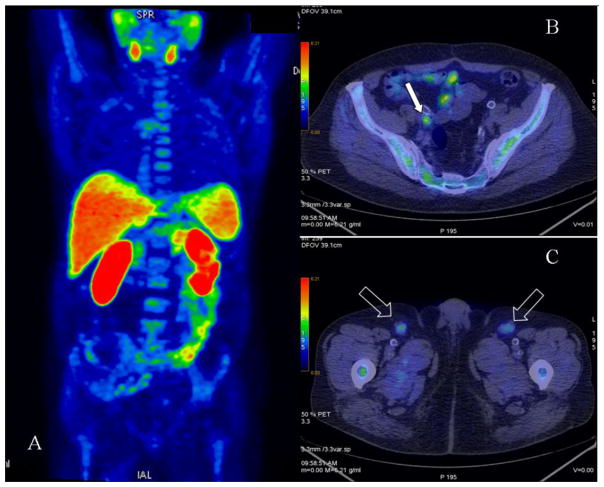

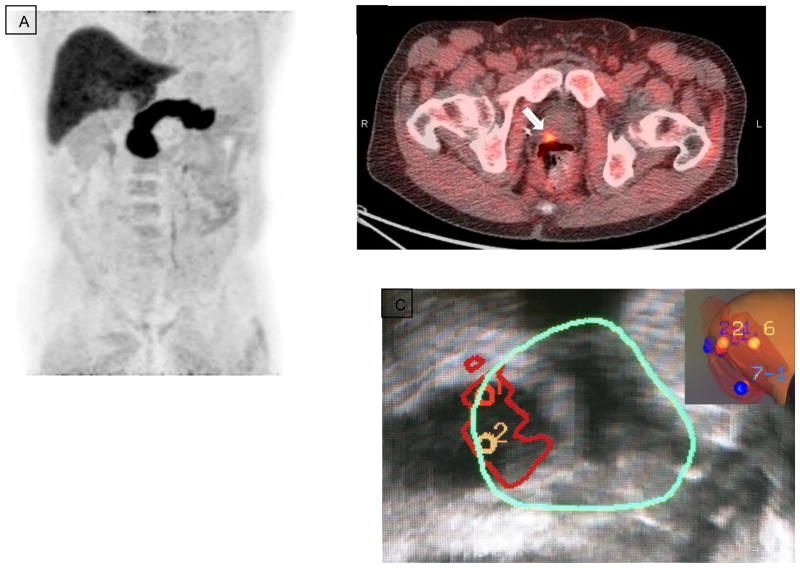

Figure 1.

11C-Choline PET in a patient post radical prostatectomy and adjuvant ADT. PSA subsequently increased to 2.3 ng/ml. (A) Maximum intensity projection (MIP) image. (B) Axial PET/CT showing increased focal uptake in small right iliac lymph node consistent with relapse (arrow). (C) Axial PET/CT showing increased uptake in bilateral inguinal nodes consistent with inflammation (arrows).

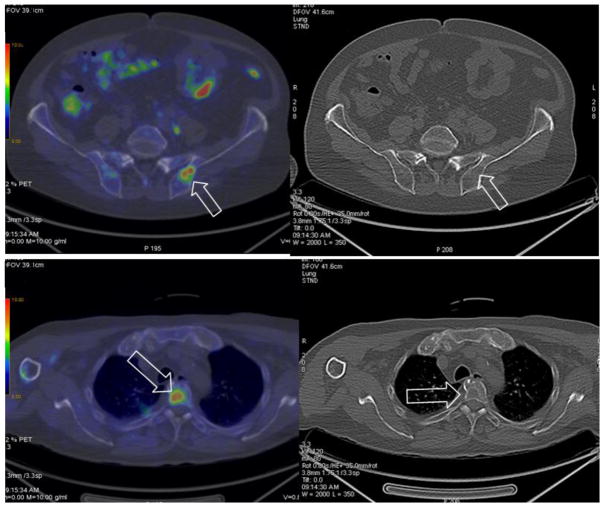

Figure 2.

11C-Choline PET in a patient with high risk prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy and ADT. The PSA suddenly increased to 33 ng/ml. (A) Axial PET/CT (left) showing increased focal uptake in the ilium with no morphological changes at corresponding CT (right) consistent with an early metastatic lesion (arrows). (B) Axial PET/CT (left) showing increased focal uptake in a thoracic vertebra corresponding to a lytic area at CT (right) consistent with another metastatic lesion (arrows).

Acetate

Acetate is a naturally occurring fatty acid precursor that is converted to acetyl-CoA, a substrate for the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Acetyl-CoA is incorporated into cholesterol and fatty acids and therefore 11C-acetate uptake is an indirect biomarker of fatty acid synthesis. This property is exploited for tumor imaging with 11C-acetate.10 Thanks to its short half-life (20 minutes), 11C-acetate delivers a relatively low effective dose (0.0049 mSv/MBq) to the patient and is a suitable compound for PET diagnostics. Most intense activity is present in pancreas, salivary glands, liver, spleen, and variably in bowel.26 No urinary excretion of tracer is measurable.26 Through 18F-Fluoroacetate has been developed, it has seen little use.27

Since fatty acid synthase is over-expressed in prostate cancer cells, 11C-acetate has been used for evaluation of this tumor. In addition, since the major elimination route of 11C-acetate is through the respiratory system, imaging can be performed without interference of urinary activity. This characteristic is particularly interesting because prostate cancer is a pelvic disease, and local relapse may be misperceived in instances of radioactive urine within the urinary bladder. Furthermore, lack of significant renal activity at imaging improves the detection of small retroperitoneal nodes.

Primary disease

11C-acetate PET/CT has been studied in the detection of primary prostate cancer as an alternative tracer to 18F-FDG. Mena et al analyzed 39 men with presumed localized disease who underwent dynamic/static abdomen-pelvic 11C-acetate PET/CT for 30-minutes and 3T multi-parametric MP-MRI prior to prostatectomy. 11C-acetate PET standardized uptake values were then compared with MP-MRI and histology. The authors found that the average SUVmax of tumors was significantly higher than that of normal prostate tissue (4.4±2.05, vs. 2.1±0.94, p<0.001) but not significantly different compared with benign prostatic hyperplasia (4.8±2.01; range 1.8 8.8). A sector-based comparison with histopathology, including all tumors > 0.5 cm, revealed a sensitivity and specificity of 61.6% and 80.0% for 11C-acetate PET/CT, and 82.3% and 95.1% for MRI, respectively. Considering only tumors >0.9 cm, 11C-acetate accuracy was comparable to that of MRI.28

Better results were obtained by Jambor et al who enrolled 36 men with untreated prostate cancer and no metastatic disease.29 A pelvic 11C-acetate PET/CT scan was performed in all patients, and a contrast enhanced MRI scan in 33 patients. After the imaging studies, 10 patients underwent prostatectomy and 26 were treated by image guided external beam radiation treatment. PET/CT, MRI and fused PET/MRI data were evaluated visually and compared with biopsy findings on a lobar level, while a sextant approach was used for patients undergoing prostatectomy. When using biopsy samples as a reference standard, the sensitivity, specificity and accuracy for visual detection of prostate cancer on a lobar level by contrast enhanced MRI was 85%, 37%, 73% and that of 11C-acetate PET/CT 88%, 41%, 74%, respectively. Fusion of PET with MRI data increased sensitivity, specificity and accuracy to 90%, 72% and 85%, respectively.

These discrepant results are probably due to different patient characteristics at enrollment and reference standards (histology in the first study and follow-up in the second). Yet, most investigators would agree that although no definitive results have been published, 11C-acetate PET/CT is probably not worthwhile for the assessment of intraprostatic tumor due to relatively low specificity and thus multiparametric MRI is preferable.30, 31

Staging

Before surgery, prostate cancer patients typically undergo computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for lymph node staging. However, neither is sensitive for detecting nodal metastasis unless the nodes are enlarged and their sensitivity ranges from 39–42%.32, 33 Because of the unreliability of imaging, nomograms based on clinical parameters, such as prostate specific antigen (PSA), T stage, and Gleason score are used to estimate the risk of nodal metastasis and may justify omission of lymphadenectomy in patients with estimated risk <5% since there is an 8–20% complication rate of lymphadenectomy.6, 7, 34–36 This approach is not ideal, however, as some men will be understaged.

11C-acetate was therefore tested for lymph nodal staging in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy. Schumacher et al analyzed 19 prostate carcinoma patients who underwent 11C-acetate PET/CT and subsequently had extended pelvic lymph-node dissection. The PET/CT results were compared with the surgical and pathological findings from 13 defined lymph node regions. The patient-by-patient based sensitivity was 90% and the specificity 67%, the positive predictive value (PPV) was 75% and the negative predictive value (NPV) 86%. From a total of 114 nodal regions, 484 lymph nodes were removed and evaluated histopathologically. Forty-six lymph nodes from 24 out of 114 (21%) nodal regions were positive for metastasis. The nodal-region-based sensitivity of 11C-acetate-PET/CT was 62%, specificity was 89%, PPV 62% and NPV 89%.37

Similar results were obtained by Haseebuddin et al who enrolled 107 men with intermediate or high-risk localized prostate cancer with negative conventional imaging.38 Patients underwent PET/CT with 11C-acetate. Five underwent lymph node (LN) staging only and 102 LN staging and prostatectomy. PET/CT findings were correlated with pathologic nodal status. PET/CT was positive for pelvic LN or distant metastasis in 36 of 107 patients (33.6%). LN metastases were present histopathologically in 25 (23.4%). The sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative-predictive values of PET/CT for detecting LN metastasis were 68.0%, 78.1%, 48.6% and 88.9% respectively. 64 patients failed: 25 with metastasis, 17 with persistent post-prostatectomy PSA >0.20 ng/mL, and 22 with biochemical recurrence (PSA >0.20 ng/mL after nadir) during follow-up for a median of 44.0 months. Treatment failure free survival was worse in PET-positive than in PET-negative patients (p<0.0001) and in those with false-positive versus true-negative scans (p<0.01), suggesting that PET may have demonstrated nodal disease not removed surgically or identified pathologically. PET positivity independently predicted failure in preoperative and postoperative multivariate models. Though 11C-acetate PET/CT was found to be overall suboptimal for nodal staging in primary prostate cancer patients, the correlation of 11C-acetate uptake with treatment failure free survival is interesting and further studies would be necessary to confirm its prognostic role.

Recurrence

Many authors have investigated the potential role of 11C-acetate PET in detecting the site of relapse in case of biochemical recurrence. Kotzerke et al found relatively good performances of 11C-acetate in patients presenting with biochemical relapse, even with low PSA values.39 In particular they investigated the potential of 11C-acetate PET to detect local recurrence in prostate cancer in patients with increasing PSA following complete prostatectomy. A total of 31 patients were studied and compared with the results of transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) combined with biopsy and clinical follow-up. TRUS followed by biopsy verified recurrence in 18 patients and ruled it out in 13 patients. PET demonstrated the local recurrence in 15/18 patients. PET also demonstrated distant lymph node involvement and bone metastases in five patients each. No focal uptake was demonstrated in the prostate bed in patients with negative biopsy. These patients had no evidence of disease during 6 months of follow-up. In the subgroup of patients with PSA <2.0 ng/ml (n=8), five patients had positive PET findings, with four of them verified by biopsy. Furthermore, the same authors obtained comparable results when 11C-acetate was tested against 11C-choline.40

Vees et al undertook a study using either 11C-acetate or 18F-choline PET/CT to detect residual or progressive subclinical disease after radical prostatectomy in case of biochemical relapse and low PSA.41 In this interesting but limited study (only 11 were patients enrolled in each acetate or choline arm), 11C-acetate PET/CT was able to detect the site of recurrent disease in more than the half of the patients (6/11). Also in this study, the authors reported no significant difference between the detection rate of 11C-acetate and 18F-choline PET /CT. Watcher et al investigated combined 11C-acetate PET and MRI in 50 patients with suspected local relapse.42 Images were fused and the addition of the information provided by 11C-acetate PET was found to be clinically useful, influencing management in 14 of 50 patients (28%). Sandblom et al evaluated 20 patients with the same characteristics and a mean PSA level of 2 ng/mL at the time of 11C-acetate PET scan.43 Surprisingly in this study 11C-acetate PET showed a very high detection rate, positive in 15/20 patients (8 single lesions and 7 multiple lesions).

Albrecht et al also found interesting preliminary results in a study that evaluated 32 prostate cancer patients with early evidence of relapse after initial radiotherapy (17 patients) or radical surgery (15 patients).44 Both groups had low median PSA at relapse (6 ng/ml after RT and 0.4 after surgery). After radiotherapy, PET showed local recurrences in 14/17 patients and 2 equivocal results. Distant disease was observed in 6 patients and an equivocal result was obtained in one. Biopsy confirmed local recurrence in the 6/17 patients in whom it was performed. PET was positive in 5/6 of these patients with biopsy-proven recurrences, the other was equivocal. Among the 15 patients scanned post-surgery, PET was positive for local recurrence in 5 patients and equivocal in 4. One obturator lymph node was positive. PSA decreased significantly after salvage radiotherapy in 8/14 patients, providing strong evidence for local recurrence. PET of these 8 patients responding to RT was positive in 3 and equivocal in 2. The authors concluded that 11C-acetate PET was valuable in the early evaluation of prostate cancer relapse.

Acetate versus choline

To date no final conclusion has been reached as to whether acetate or choline tracers are superior. Both radiotracers perform in a similar manner in published studies. Choline as well as acetate have insufficient diagnostic accuracy for evaluation of the primary tumour and inability to differentiate prostate carcinoma from benign prostate hyperplasia, chronic prostatitis and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. Regarding lymph node staging, choline tracers have demonstrated a high specificity. Unfortunately, the sensitivity is only moderate. For staging recurrent disease, sensitivity depends on the level of serum PSA (PSA should be >2 ng/ml). This applies to both choline and acetate. 11C-acetate has never been tested in large prostate cancer patient populations and despite overall relatively good results (equal to 11C-choline), 11C-acetate is not extensively used in clinical practice as are the choline radiotracers.45 Figures 3 and 4 are representative images of 11C-acetate PET imaging of prostate cancer.

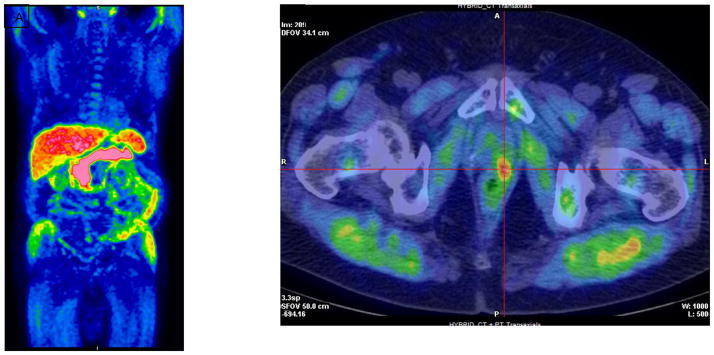

Figure 3.

11C-Acetate PET in a patient who was 5 months post radical prostatectomy with a PSA of 1.64 ng/ml. (A) MIP image. (B) Axial PET/CT demonstrates focal radiotracer activity in the left side of the prostate bed (crosshairs). (Images courtesy of Reginald Dusing, MD, University of Kansas)

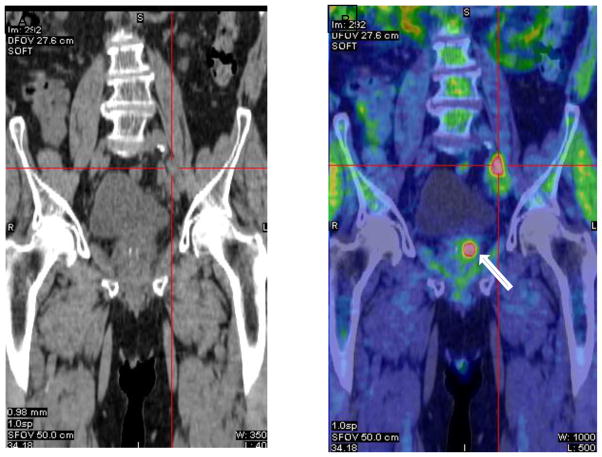

Figure 4.

11C-Acetate PET in a patient post intensity modulated radiation therapy with rising PSA of 25.4 ng/ml. (A) Coronal CT demonstrates prominent nodes at left common iliac bifurcation (crosshairs). (B) Coronal PET/CT shows intense activity within these nodes (crosshair) and also focal activity within the local recurrence in the left prostate (arrow). (Images courtesy of Reginald Dusing, MD, University of Kansas)

Amino Acid PET Including Fluciclovine

Another aspect of the metabolome of prostate cancer which can be exploited for molecular imaging is that of amino acids, since amino acid transport and metabolism is upregulated in prostate and other cancers.46–49 Many amino acid transporter systems are over-expressed in prostate cancer, particularly the system ASC transporter ASCT2 and the system L transporter LAT1, which have been associated with tumor aggressiveness and poor survival.50–59 In addition glutamine utilization as an energy source within cancer cells and the role of leucine and glutamine in mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) cancer signalling have drawn attention for potential therapeutic targeting strategies.48, 51, 60–65 Both natural and synthetic radiolabeled amino acids have been utilized for prostate cancer imaging and tumor visualization is considered mainly a reflection of amino acid transport itself rather than metabolism.47, 61, 66

The first examples of radiolabeled amino acid derived radiotracers for prostate cancer imaging were based on naturally occurring amino acids such as methionine and tryptophan.67–70 L-[11C]methionine (MET) was initially compared with FDG for PET imaging in patients with progressive prostate cancer resulting in higher uptake and sensitivity by MET compared with FDG for bone and soft tissue lesions, for example in one study with 12 patients detecting 72% (251/348) of lesions with MET vs 48% (167/348) with FDG.67, 68 MET has also been studied in the setting of primary prostate cancer with overall good visualization of the primary tumor but with false positivity reported due to BPH and chronic prostatitis.69, 71 Neuroendocrine differentiation has also been implicated in refractory prostate cancer and the tryptophan derived L-[1-11C]5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) PET radiotracer has been studied with some good results in a small series of patients with hormone refractory prostatic cancer.70, 72, 73

While initial studies with radiolabeled naturally occurring amino acids served as proof of principle for utility with prostate cancer, radiolabeled non-natural or synthetic amino acids have also been developed for cancer imaging.74 Non-natural amino acids have certain advantages for imaging including greater ease in synthesis, the ability to radiolabel with longer lived radionuclides such as fluorine-18, and simplified kinetics due to the radiotracer not undergoing metabolism.61 One such fluorinated synthetic amino acid PET radiotracer which has been subject to the most extensive investigation for prostate cancer is anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (FACBC or fluciclovine).75 Fluciclovine (as it will be referenced for the remainder of this review) is not metabolized or incorporated into proteins 46, 53, 76–78.

Normal biodistribution of fluciclovine activity includes minimal brain and excreted urinary activity which are advantageous for imaging the cerebrum, retroperitoneum and pelvis.79 Similar to other amino acid based PET radiotracers, highest intensity is present in pancreas and less so in liver, marrow, salivary glands, lymphoid tissues and pituitary. Dosimetry is also similar to most other fluorinated PET radiotracers such as FDG.80–82 In-vitro experiments with fluciclovine reported uptake in DU145 prostate carcinoma cells and it was initially believed that the radiotracer was transported in a manner most similar to leucine via the LAT1 transporter.76,83 Subsequent investigations demonstrated that fluciclovine transport is more similar to glutamine, mostly mediated through the ASCT2 transporter. Though with decreasing pH occurring within tumor and with castration resistance, LAT1 transport may in fact predominate.53, 77, 84, 85 Imaging of a rat orthotopic prostate cancer model demonstrated that fluciclovine better visualized tumor with lower bladder accumulation compared to FDG.76

A pilot study in 9 patients with primary prostate carcinoma and 6 patients with suspected recurrence reported the ability to visualize both primary and recurrent cancer in the prostate/bed and that extraprostatic foci were identified despite unrevealing imaging with 111In-capromab-pendetide.86, 87 Time activity curves typically peak at 5–20 minutes with subsequent washout; thus, early imaging is recommended.

This early study led to a more comprehensive NIH funded clinical trial (NCT00562315) involving 128 fluciclovine studies in 115 patients with biochemical failure after prostatectomy or non-prostatectomy therapy for prostate cancer and with bone scans negative for skeletal disease. The study was designed for clinical relevance to separately determine diagnostic performance in both prostate/bed and extraprostatic locations. Histologic proof on a per patient basis for true positivity was established in 96.1% of index lesions in the most comprehensive report of the trial in which 93 patients underwent fluciclovine PET-CT and 111In-capromab-pendetide within 90 days.88, 89 In the prostate/bed, fluciclovine PET had 90.2% sensitivity, 40.0% specificity, 73.6% accuracy, 75.3% positive predictive value (PPV) and 66.7% negative predictive value (NPV) compared to 111In-capromab pendetide with 67.2%, 56.7%, 63.7%, 75.9% and 45.9%, respectively. For presence or absence of extraprostatic disease, fluciclovine PET had 55.0% sensitivity, 96.7%specificity, 72.9% accuracy, 95.7% PPV and 61.7% NPV, compared to 111In-capromab pendetide with 10.0%, 86.7%, 42.9%, 50.0% and 41.9%, respectively. Fluciclovine detected 14 more patients with positive prostate/bed recurrence (55 vs 41) and 18 more patients with extraprostatic involvement (22 vs 4), which resulted in 25.7% of patients being upstaged. Superior overall detection of disease in comparison to computed tomography has also been reported based on data from this trial.90

Since choline kinase is upregulated in prostate cancer, 11C-choline and 18F-choline PET have gained prominence as effective radiotracers in the imaging of prostate cancer, especially for recurrent disease.91 Thus, there was interest comparing a choline radiotracer to fluciclovine in the same patient cohort. A 100 patient clinical trial was recently completed at the University of Bologna in which post-prostatectomy patients with PSA failure had both 11C-choline and fluciclovine PET-CT. Preliminary and interim analyses on 15 and 50 patients, respectively, revealed a higher detection rate of fluciclovine versus 11C-choline at low, intermediate, and high PSA levels.92, 93

A final analysis of 89 patients who could be followed-up for one year revealed sensitivity of 37%, specificity of 67%, PPV of 97%, NPV of 4%, and accuracy of 38% for fluciclovine versus 32%, 40%, 90%, 3%, and 32% respectively for choline.94 In general, fluciclovine had superior performance than choline, detecting a higher number of true positive and true negative lesions in the prostate bed, lymph nodes, and bone. Practical advantages for fluciclovine were also reported including lower physiologic background aiding lesion conspicuity. In vitro studies in prostate cancer cells have reported relative fluciclovine uptake greater than that of methionine, choline, and acetate.95

Other trials have also reported on the utility of fluciclovine for staging of primary and metastatic prostate cancer.96, 97 In a retrospective study of 26 patients with suspect or proven recurrence, there was a 53.3% overall positivity rate with fluciclovine varying with absolute PSA and doubling time.98 In a multicenter phase 2b Japanese trial for primary prostate cancer staging, 68 patients who had conventional staging with CT and bone scan also underwent fluciclovine PET-CT.99 While overall accuracy between conventional and fluciclovine staging was similar, fluciclovine PET-CT detected more sub-centimeter (5–9mm short axis) nodes in 23 regions in 13 patients and also detected 7 more patients with skeletal lesions, though this particular study was not optimized to establish the ground truth of these findings.

It is likely that fluciclovine will prove most useful for detection of recurrent disease and for staging of high risk primary prostate cancer than for detection and characterization of primary disease. In a 10 patient exploratory trial for primary prostate carcinoma, though SUVmax was significantly higher in malignant versus nonmalignant sextants, there was overlap in uptake intensity between benign and malignant sextants.100 In another study in 21 patients with primary prostate cancer in comparison to MP-MR, a sector based analysis of fluciclovine demonstrated a sensitivity of 67% and a specificity of 66%, versus T2-weighted MR with 73% sensitivity and 79% specificity. Fluciclovine activity in prostate cancer was significantly higher compared with normal prostate, but was not significantly different from benign prostatic hypertrophy.3 The highest PPV of 82% though was achieved through a combination of fluciclovine and MR localization for tumor. Ongoing investigation into the utility of incorporating fluciclovine guidance for transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy continues.101 Figure 5 is an example of fluciclovine guided biopsy for locally recurrent disease.

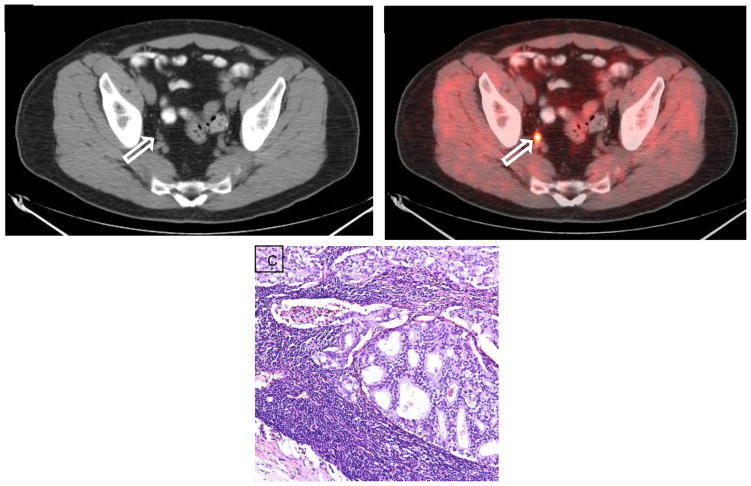

Figure 5.

Fluciclovine PET in a patient post brachytherapy and salvage cryotherapy with rising PSA to 6.59 post multiple negative biopsies. (A) MIP image. (B) Axial PET-CT demonstrating focal activity in the right prostate base at junction of seminal vesicle (arrow). Abnormal activity was also present in the apex (not shown) (C) Fluciclovine-directed 3D ultrasound targeted biopsy verified recurrent disease. (Image courtesy of Baowei Fei, PhD, Emory University)

As to the current status of fluciclovine, industry sponsored phase 3b trials in the US and the UK have commenced. In addition, a New Drug Application (NDA) in the detection of recurrent prostate carcinoma for fluciclovine has been accepted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under priority review based on data presented above which also includes more than 700 prostate cancer patients studied in the United States, Italy and Norway.102 Figure 6 depicts nodal detection with fluciclovine PET/CT.

Figure 6.

Fluciclovine PET in a patient post external beam radiation therapy and prostatectomy with rising PSA to 1.34 ng/ml and no abnormal findings in the prostate bed. (A) Axial CT demonstrates 8 × 6 mm right internal iliac node with abnormal uptake on corresponding (B) fluciclovine axial PET-CT (arrows) confirmed to be metastasis by CT guided biopsy. (C) H&E stained section of the lymph node (40×) demonstrates metastatic adenocarcinoma from a prostate primary.

Bombesin

Another target for prostate cancer molecular imaging that is under active investigation involves the gastrin releasing peptide receptor (GRPR) which is reported to be overexpressed in prostate cancer with little to no activity in normal or hypertrophied prostate tissue.49 Bombesin analogues are shortened and more stable versions of the full 27-amino acid mammalian gastrin releasing peptide (GRP), involved in multiple signalling pathways, but which has insufficient in-vivo stability in itself to be the basis of an effective radiotracer.103, 104 GRPR overexpression has been reported in 63–100% of primary prostate cancer lesions and in 50–85% of nodal and skeletal metastases.103, 105 Both receptor agonist and antagonist ligands have been labeled with a variety of radionuclides including 18F, 64Cu, and 68Ga.103, 105–113

[68Ga]-labeled DOTA-4-amino-1-carboxymethyl-piperidine-D-Phe-Gln-Trp-Ala-Val-Gly-His-Sta-Leu-NH2 peptide (BAY86-7548) is a radiolabeled bombesin receptor antagonist in which a first-in-human trial has been completed in 11 patients with primary prostate cancer and 3 with recurrence.106 The authors report 88% sensitivity and 81% specificity for primary disease on a sextant level, and detection of recurrent disease in the bed and nodes in 2 patients, while in a 3rd hormone refractory recurrent patient, skeletal disease was not detected. Six false positive foci due to BPH were also noted. In another study with this radiotracer, also known as 68Ga-RM2, 7 patients were imaged who also underwent Glu-NH-CO-NH-Lys-(Ahx)-[68Ga(HBED-CC)] (68Ga-PSMA) PET.109 In this study there were similar patterns of uptake in abnormal tissue but in one patient pelvic nodal and seminal vesicle involvement was only seen with 68Ga-PSMA, while in 2 other patients periaortic malignant nodes were better seen with 68Ga-RM2. These findings likely reflect relative differences in receptor expression as well as lesions conspicuity due to patterns of normal biodistribution. Figure 7 is an example of 68Ga-RM2 imaging.

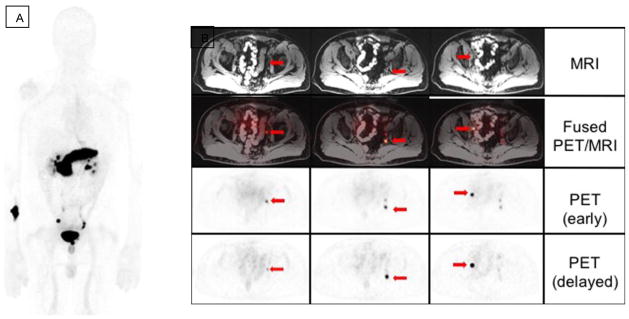

Figure 7.

68Ga RM2 PET/MRI in a patient with treated prostate adenocarcinoma, now with biochemical recurrence (PSA: 3.25 ng/ml) and negative CT and bone scan. (A) MIP image. (B) Early and delayed axial PET/MRI demonstrate multiple subcentimeter pelvic lymph nodes with high uptake on the initial and delayed 68Ga RM2 PET acquisitions (arrows). (Images courtesy of Andrei Iagaru, MD, Stanford University)

A fluorinated bombesin PET radiotracer 18F-BAY 86-4367 has been studied with early promising results in preclinical work and in humans with higher activity in prostate PC-3 and LNCaP xenograft models than 18F-fluoroethylcholine, 11C-choline, and 18F-FDG.110–112 In a study with 5 patients with primary prostate cancer and 5 with biochemical recurrence, 3/5 primary tumors were visualized with this PET radiotracer and 2/5 with recurrent disease.111 Interestingly some lesions were better visualized in concurrent 18F-fluorocholine PET-CT and others with the bombesin PET radiotracer, possibly reflecting differing aspects of tumor biology worthy of further study. A 64Cu labeled GRPR antagonist, 64Cu-CB-TE2A-AR-06, has also shown some promising preliminary results in a preclinical animal model as well as first in man studies in which there was uptake in 2/3 primary prostate cancers.107

18F-Fluorodihydrotestosterone (FDHT)

Androgens play an important role in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer and overexpression of androgen receptors (AR) occurs in all stages of the disease. Thus a radiotracer which probes the molecular pathway of dihydrotesterone which is the primary ligand binding to the androgen receptor may serve a useful role in both clinical and research imaging of prostate cancer.

A PET radiotracer based on dihydrotesterone, 16β-18F-fluoro-5α-dihydrotestosterone (FDHT), which binds to sex hormone binding globulin and passively diffuses into the cytoplasm where it binds to the androgen receptor, has been developed and tested in a variety of settings including utility in assessing the pharmacokinetics of newly developed anti-androgen drugs.49, 114 In the initial report of this radiotracer in humans, Larson et al studied uptake in 7 patients with progressive metastatic prostate cancer compared with FDG.115 FDHT was positive in 46/59 lesions while FDG was positive in 57/59 lesions. Hormonal therapy reduced FDHT activity in 2 patients receiving testosterone and 1 patient receiving 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG), an AR degrading pharmaceutical.

FDHT has proven useful to assess saturation of androgen receptor binding and optimal dosing with the anti-androgens, ARN-509 and MDV3100 (enzalutamide).116, 117 Finally, a study utilizing both FDHT and FDG PET in 38 patients with skeletal metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer reported that overall survival correlated with number of lesions on both studies, and that overall survival correlated with maximum intensity on FDHT, yet the same correlation was not seen with FDG.118 On the basis findings from these studies, 3 major patterns of metastatic activity have been described: AR dominant, glycolysis dominant, and AR-glycolyses concordant.119 These interesting observations may lead to insights useful for personalizing future therapy and as a vehicle for further drug discovery.

Other Emerging PET Radiotracers

Among other amino acid imaging, cationic system ATB0,+ transport with O-2((2-[18F]fluoroethyl)methyl-amino)ethyltyrosine ([18F]FEMAET) has been studied in prostate cancer PC3 cells and mice xenografts.59 A system X−c PET radiotracer (4S)-4-(3-[18F]fluoropropyl)-L-glutamate ([18F]FSPG) has also been developed with good visualization of 5/10 patients with primary prostate cancer and 7/10 patients with recurrent or metastatic disease.120 Finally,11C and 18F system A transport radiotracers are being studied in the preclinical setting of prostate cancer in preparation for human translation.46, 121, 122

The interrogation of a wide variety of prostate cancer related receptors is possible with PET and other nuclear scintigraphic methods. The targeting of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide receptor 1 (VPAC-1) which is upregulated in prostate cancer but not in benign prostatic hypertrophy has also been reported in early work with the PET radiotracer 64Cu-TP3805 in a study of 25 patients with primary prostate cancer.123 Finally, 18F and 64Cu radiotracers for imaging the urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) which is overexpressed in human prostate cancer and also associated with a propensity for metastases and poor prognosis have been recently reported.124, 125 A first in human study with 64Cu-DOTA-AE105, a radiolabeled chelated small peptide ligand of the uPAR receptor, demonstrated proof of principle in 4 patients with prostate cancer.124

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Breeuwsma AJ, Pruim J, Jongen MM, et al. In vivo uptake of [11C]choline does not correlate with cell proliferation in human prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32(6):668–73. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1741-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Husarik DB, Miralbell R, Dubs M, et al. Evaluation of [(18)F]-choline PET/CT for staging and restaging of prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35(2):253–63. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turkbey B, Mena E, Shih J, et al. Localized prostate cancer detection with 18F FACBC PET/CT: comparison with MR imaging and histopathologic analysis. Radiology. 2014;270(3):849–56. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Testa C, Schiavina R, Lodi R, et al. Prostate cancer: sextant localization with MR imaging, MR spectroscopy, and. Radiology. 2007;244(3):797–806. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2443061063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farsad M, Schiavina R, Castellucci P, et al. Detection and localization of prostate cancer: correlation of (11)C-choline PET/CT with histopathologic step-section analysis. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(10):1642–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briganti A, Chun FKH, Salonia A, et al. Validation of a nomogram predicting the probability of lymph node invasion based on the extent of pelvic lymphadenectomy in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2006;98(4):788–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briganti A, Chun FKH, Salonia A, et al. Complications and other surgical outcomes associated with extended pelvic lymphadenectomy in men with localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2006;50(5):1006–13. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65(2):467–79. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiavina R, Scattoni V, Castellucci P, et al. 11C-choline positron emission tomography/computerized tomography for preoperative lymph-node staging in intermediate-risk and high-risk prostate cancer: comparison with clinical staging nomograms. Eur Urol. 2008;54(2):392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beheshti M, Imamovic L, Broinger G, et al. 18F choline PET/CT in the preoperative staging of prostate cancer in patients with intermediate or high risk of extracapsular disease: a prospective study of 130 patients. Radiology. 2010;254(3):925–33. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poulsen MH, Bouchelouche K, Hoilund-Carlsen PF, et al. [18F]fluoromethylcholine (FCH) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) for lymph node staging of prostate cancer: a prospective study of 210 patients. BJU Int. 2012;110(11):1666–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kataja VV, Bergh J. ESMO Minimum Clinical Recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of prostate cancer. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2005;16(Suppl 1):i34–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Picchio M, Messa C, Landoni C, et al. Value of [11C]choline-positron emission tomography for re-staging prostate cancer: a comparison with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography. J Urol. 2003;169(4):1337–40. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000056901.95996.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richter JA, Rodriguez M, Rioja J, et al. Dual tracer 11C-choline and FDG-PET in the diagnosis of biochemical prostate cancer relapse after radical treatment. Mol Imaging Biol. 2010;12(2):210–7. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0243-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krause BJ, Souvatzoglou M, Tuncel M, et al. The detection rate of [11C]choline-PET/CT depends on the serum PSA-value in patients with biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35(1):18–23. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giovacchini G, Picchio M, Garcia-Parra R, et al. [11C]choline positron emission tomography/computerized tomography for early detection of prostate cancer recurrence in patients with low increasing prostate specific antigen. J Urol. 2013;189(1):105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell CR, Lowe VJ, Rangel LJ, et al. Operational characteristics of (11)c-choline positron emission tomography/computerized tomography for prostate cancer with biochemical recurrence after initial treatment. J Urol. 2013;189(4):1308–13. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castellucci P, Fuccio C, Nanni C, et al. Influence of trigger PSA and PSA kinetics on 11C-Choline PET/CT detection rate in patients with biochemical relapse after radical prostatectomy. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(9):1394–400. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.061507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castellucci P, Fuccio C, Rubello D, et al. Is there a role for (1)(1)C-choline PET/CT in the early detection of metastatic disease in surgically treated prostate cancer patients with a mild PSA increase <1.5 ng/ml? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38(1):55–63. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giovacchini G, Picchio M, Parra RG, et al. Prostate-specific antigen velocity versus prostate-specific antigen doubling time for prediction of 11C choline PET/CT in prostate cancer patients with biochemical failure after radical prostatectomy. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37(4):325–31. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31823363b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuccio C, Schiavina R, Castellucci P, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy influences the uptake of 11C-choline in patients with recurrent prostate cancer: the preliminary results of a sequential PET/CT study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38(11):1985–9. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1867-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ceci F, Schiavina R, Castellucci P, et al. 11C-choline PET/CT scan in patients with prostate cancer treated with intermittent ADT: a sequential PET/CT study. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38(7):e279–82. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182952c4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ceci F, Castellucci P, Graziani T, et al. (11)C-Choline PET/CT in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients treated with docetaxel. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43(1):84–91. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceci F, Castellucci P, Graziani T, et al. 11C-choline PET/CT detects the site of relapse in the majority of prostate cancer patients showing biochemical recurrence after EBRT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41(5):878–86. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2655-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitajima K, Murphy RC, Nathan MA, et al. Detection of recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: comparison of. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2014;55(2):223–32. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.123018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seltzer MA, Jahan SA, Sparks R, et al. Radiation dose estimates in humans for (11)C-acetate whole-body PET. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2004;45(7):1233–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ponde DE, Dence CS, Oyama N, et al. 18F-fluoroacetate: a potential acetate analog for prostate tumor imaging--in vivo evaluation of 18F-fluoroacetate versus 11C-acetate. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48(3):420–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mena E, Turkbey B, Mani H, et al. 11C-Acetate PET/CT in localized prostate cancer: a study with MRI and histopathologic correlation. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(4):538–45. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.096032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jambor I, Borra R, Kemppainen J, et al. Functional imaging of localized prostate cancer aggressiveness using 11C-acetate PET/CT and 1H-MR spectroscopy. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2010;51(11):1676–83. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.078667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hotker AM, Mazaheri Y, Aras O, et al. Assessment of Prostate Cancer Aggressiveness by Use of the Combination of Quantitative DWI and Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jambor I, Borra R, Kemppainen J, et al. Improved detection of localized prostate cancer using co-registered MRI and. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(11):2966–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parker CC, Husband J, Dearnaley DP. Lymph node staging in clinically localized prostate cancer. Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases. 1999;2(4):191–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hovels AM, Heesakkers RAM, Adang EM, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of CT and MRI in the staging of pelvic lymph nodes in patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Clin Radiol. 2008;63(4):387–95. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makarov DV, Trock BJ, Humphreys EB, et al. Updated nomogram to predict pathologic stage of prostate cancer given prostate-specific antigen level, clinical stage, and biopsy Gleason score (Partin tables) based on cases from 2000 to 2005. Urology. 2007;69(6):1095–101. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cagiannos I, Karakiewicz P, Eastham JA, et al. A preoperative nomogram identifying decreased risk of positive pelvic lymph nodes in patients with prostate cancer. The Journal of urology. 2003;170(5):1798–803. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091805.98960.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bishoff JT, Reyes A, Thompson IM, et al. Pelvic lymphadenectomy can be omitted in selected patients with carcinoma of the prostate: development of a system of patient selection. Urology. 1995;45(2):270–4. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(95)80017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schumacher MC, Radecka E, Hellstrom M, et al. [11C]Acetate positron emission tomography-computed tomography imaging of prostate cancer lymph-node metastases correlated with histopathological findings after extended lymphadenectomy. Scandinavian journal of urology. 2015;49(1):35–42. doi: 10.3109/21681805.2014.932840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haseebuddin M, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA, et al. 11C-acetate PET/CT before radical prostatectomy: nodal staging and treatment failure prediction. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2013;54(5):699–706. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.111153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotzerke J, Volkmer BG, Neumaier B, et al. Carbon-11 acetate positron emission tomography can detect local recurrence of prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29(10):1380–4. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0882-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kotzerke J, Volkmer BG, Glatting G, et al. Intraindividual comparison of [11C]acetate and [11C]choline PET for detection of metastases of prostate cancer. Nuklearmedizin. 2003;42(1):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vees H, Buchegger F, Albrecht S, et al. 18F-choline and/or 11C-acetate positron emission tomography: detection of residual or progressive subclinical disease at very low prostate-specific antigen values (<1 ng/mL) after radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2007;99(6):1415–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wachter S, Tomek S, Kurtaran A, et al. 11C-acetate positron emission tomography imaging and image fusion with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with recurrent prostate cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(16):2513–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.5279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandblom G, Sorensen J, Lundin N, et al. Positron emission tomography with C11-acetate for tumor detection and localization in patients with prostate-specific antigen relapse after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2006;67(5):996–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albrecht S, Buchegger F, Soloviev D, et al. (11)C-acetate PET in the early evaluation of prostate cancer recurrence. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34(2):185–96. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brogsitter C, Zophel K, Kotzerke J. 18F-Choline, 11C-choline and 11C-acetate PET/CT: comparative analysis for imaging prostate cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40(Suppl 1):S18–27. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McConathy J, Yu W, Jarkas N, et al. Radiohalogenated nonnatural amino acids as PET and SPECT tumor imaging agents. Med Res Rev. 2012;32(4):868–905. doi: 10.1002/med.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jager PL, Vaalburg W, Pruim J, et al. Radiolabeled amino acids: basic aspects and clinical applications in oncology. J Nucl Med. 2001;42(3):432–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakanishi T, Tamai I. Solute carrier transporters as targets for drug delivery and pharmacological intervention for chemotherapy. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100(9):3731–50. doi: 10.1002/jps.22576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wibmer AG, Burger IA, Sala E, et al. Molecular Imaging of Prostate Cancer. Radiographics. 2015:150059. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heublein S, Kazi S, Ogmundsdottir MH, et al. Proton-assisted amino-acid transporters are conserved regulators of proliferation and amino-acid-dependent mTORC1 activation. Oncogene. 2010;29(28):4068–79. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fuchs BC, Bode BP. Amino acid transporters ASCT2 and LAT1 in cancer: partners in crime? Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15(4):254–66. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smolarz K, Krause BJ, Graner FP, et al. (S)-4-(3-18F-fluoropropyl)-L-glutamic acid: an 18F-labeled tumor-specific probe for PET/CT imaging--dosimetry. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(6):861–6. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.112581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okudaira H, Shikano N, Nishii R, et al. Putative transport mechanism and intracellular fate of trans-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid in human prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(5):822–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.086074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sakata T, Ferdous G, Tsuruta T, et al. L-type amino-acid transporter 1 as a novel biomarker for high-grade malignancy in prostate cancer. Pathol Int. 2009;59(1):7–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2008.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Segawa A, Nagamori S, Kanai Y, et al. L-type amino acid transporter 1 expression is highly correlated with Gleason score in prostate cancer. Molecular and clinical oncology. 2013;1(2):274–80. doi: 10.3892/mco.2012.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cole KA, Chuaqui RF, Katz K, et al. cDNA sequencing and analysis of POV1 (PB39): a novel gene up-regulated in prostate cancer. Genomics. 1998;51(2):282–7. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Q, Tiffen J, Bailey CG, et al. Targeting amino acid transport in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: effects on cell cycle, cell growth, and tumor development. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(19):1463–73. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chuaqui RF, Englert CR, Strup SE, et al. Identification of a novel transcript up-regulated in a clinically aggressive prostate carcinoma. Urology. 1997;50(2):302–7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muller A, Chiotellis A, Keller C, et al. Imaging tumour ATB0,+ transport activity by PET with the cationic amino acid O-2((2-[18F]fluoroethyl)methyl-amino)ethyltyrosine. Mol Imaging Biol. 2014;16(3):412–20. doi: 10.1007/s11307-013-0711-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Q, Hardie RA, Hoy AJ, et al. Targeting ASCT2-mediated glutamine uptake blocks prostate cancer growth and tumour development. J Pathol. 2015;236(3):278–89. doi: 10.1002/path.4518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang C, McConathy J. Radiolabeled amino acids for oncologic imaging. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(7):1007–10. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.113100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gurel B, Iwata T, Koh CM, et al. Nuclear MYC protein overexpression is an early alteration in human prostate carcinogenesis. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(9):1156–67. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Q, Bailey CG, Ng C, et al. Androgen receptor and nutrient signaling pathways coordinate the demand for increased amino acid transport during prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2011;71(24):7525–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burgio SL, Fabbri F, Seymour IJ, et al. Perspectives on mTOR inhibitors for castration-refractory prostate cancer. Current cancer drug targets. 2012;12(8):940–9. doi: 10.2174/156800912803251234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fendt SM, Bell EL, Keibler MA, et al. Metformin decreases glucose oxidation and increases the dependency of prostate cancer cells on reductive glutamine metabolism. Cancer Res. 2013;73(14):4429–38. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ikotun OF, Marquez BV, Huang C, et al. Imaging the L-type amino acid transporter-1 (LAT1) with Zr-89 immunoPET. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Macapinlac HA, Humm JL, Akhurst T, et al. Differential Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics of L-[1-(11)C]-Methionine and 2-[(18)F] Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) in Androgen Independent Prostate Cancer. Clin Positron Imaging. 1999;2(3):173–81. doi: 10.1016/s1095-0397(99)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nunez R, Macapinlac HA, Yeung HW, et al. Combined 18F-FDG and 11C-methionine PET scans in patients with newly progressive metastatic prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2002;43(1):46–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Toth G, Lengyel Z, Balkay L, et al. Detection of prostate cancer with 11C-methionine positron emission tomography. J Urol. 2005;173(1):66–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000148326.71981.44. discussion 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kalkner KM, Ginman C, Nilsson S, et al. Positron emission tomography (PET) with 11C-5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostatic adenocarcinoma. Nucl Med Biol. 1997;24(4):319–25. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(97)00064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shiiba M, Ishihara K, Kimura G, et al. Evaluation of primary prostate cancer using 11C-methionine-PET/CT and 18F-FDG-PET/CT. Ann Nucl Med. 2012;26(2):138–45. doi: 10.1007/s12149-011-0551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Puccetti L, Supuran CT, Fasolo PP, et al. Skewing towards neuroendocrine phenotype in high grade or high stage androgen-responsive primary prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2005;48(2):215–21. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.03.018. Discussion 21–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.di Sant’Agnese PA. Neuroendocrine differentiation in carcinoma of the prostate. Diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications. Cancer. 1992;70(1 Suppl):254–68. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1+<254::aid-cncr2820701312>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hubner KF, Thie JA, Smith GT, et al. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) with 1-Aminocyclobutane-1-[(11)C]carboxylic Acid (1-[(11)C]-ACBC) for Detecting Recurrent Brain Tumors. Clin Positron Imaging. 1998;1(3):165–73. doi: 10.1016/s1095-0397(98)00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shoup TM, Olson J, Hoffman JM, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of [18F]1-amino-3-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid to image brain tumors. J Nucl Med. 1999;40(2):331–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oka S, Hattori R, Kurosaki F, et al. A Preliminary Study of Anti-1-Amino-3-18F-Fluorocyclobutyl-1-Carboxylic Acid for the Detection of Prostate Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(1):46–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oka S, Okudaira H, Yoshida Y, et al. Transport mechanisms of trans-1-amino-3-fluoro[1-(14)C]cyclobutanecarboxylic acid in prostate cancer cells. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39(1):109–19. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Washburn LC, Sun TT, Byrd B, et al. 1-aminocyclobutane[11C]carboxylic acid, a potential tumor-seeking agent. J Nucl Med. 1979;20(10):1055–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schuster DM, Nanni C, Fanti S, et al. Anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid: physiologic uptake patterns, incidental findings, and variants that may simulate disease. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(12):1986–92. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.143628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nye JA, Schuster DM, Yu W, et al. Biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of the synthetic nonmetabolized amino acid analogue anti-18F-FACBC in humans. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(6):1017–20. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.040097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Asano Y, Inoue Y, Ikeda Y, et al. Phase I clinical study of NMK36: a new PET tracer with the synthetic amino acid analogue anti-[18F]FACBC. Ann Nucl Med. 2011;25(6):414–8. doi: 10.1007/s12149-011-0477-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McParland BJ, Wall A, Johansson S, et al. The clinical safety, biodistribution and internal radiation dosimetry of [(18)F]fluciclovine in healthy adult volunteers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40(8):1256–64. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Martarello L, McConathy J, Camp VM, et al. Synthesis of syn- and anti-1-amino-3-[18F]fluoromethyl-cyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (FMACBC), potential PET ligands for tumor detection. J Med Chem. 2002;45(11):2250–9. doi: 10.1021/jm010242p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ono M, Oka S, Okudaira H, et al. [(14)C]Fluciclovine (alias anti-[(14)C]FACBC) uptake and ASCT2 expression in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells. Nucl Med Biol. 2015;42(11):887–92. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Okudaira H, Nakanishi T, Oka S, et al. Kinetic analyses of trans-1-amino-3-[18F]fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid transport in Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing human ASCT2 and SNAT2. Nucl Med Biol. 2013;40(5):670–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schuster D, Nye J, Nieh P, et al. Initial Experience with the Radiotracer Anti-1-amino-3-[F-18]Fluorocyclobutane-1-Carboxylic Acid (Anti-[F-18]FACBC) with PET in Renal Carcinoma. Molecular Imaging and Biology. 2009;11(6):434–8. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schuster D, Votaw J, Nieh P, et al. Initial experience with the radiotracer anti-1-amino-3-F-18-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid with PET/CT in prostate carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(1):56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schuster DM, Savir-Baruch B, Nieh PT, et al. Detection of recurrent prostate carcinoma with anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid PET/CT and 111In-capromab pendetide SPECT/CT. Radiology. 2011;259(3):852–61. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11102023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schuster DM, Nieh PT, Jani AB, et al. Anti-3-[(18)F]FACBC positron emission tomography-computerized tomography and (111)In-capromab pendetide single photon emission computerized tomography-computerized tomography for recurrent prostate carcinoma: results of a prospective clinical trial. J Urol. 2014;191(5):1446–53. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.10.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Odewole O, Tade FI, Oyenuga O, et al. Recurrent Prostate Cancer Detection with Anti-3-[18F] FACBC PET-CT: Comparison with CT. Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America; November, 2014; Chicago, Il. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ackerstaff E, Pflug BR, Nelson JB, et al. Detection of increased choline compounds with proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy subsequent to malignant transformation of human prostatic epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(9):3599–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nanni C, Schiavina R, Boschi S, et al. Comparison of 18F-FACBC and 11C-choline PET/CT in patients with radically treated prostate cancer and biochemical relapse: preliminary results. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40(Suppl 1):S11–7. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nanni C, Schiavina R, Brunocilla E, et al. 18F-Fluciclovine PET/CT for the Detection of Prostate Cancer Relapse: A Comparison to 11C-Choline PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40(8):e386–91. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nanni C, Zanoni L, Pultrone C, et al. F-FACBC (anti1-amino-3-F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid) versus C-choline PET/CT in prostate cancer relapse: results of a prospective trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Okudaira H, Oka S, Ono M, et al. Accumulation of trans-1-amino-3-[(18)F]fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid in prostate cancer due to androgen-induced expression of amino acid transporters. Mol Imaging Biol. 2014;16(6):756–64. doi: 10.1007/s11307-014-0756-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sorensen J, Owenius R, Lax M, et al. Regional distribution and kinetics of [18F]fluciclovine (anti-[18F]FACBC), a tracer of amino acid transport, in subjects with primary prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40(3):394–402. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Inoue Y, Asano Y, Satoh T, et al. Phase IIa Clinical Trial of Trans-1-Amino-3-18F-Fluoro-Cyclobutyl-Carboxylic Acid in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Asia Oceania J Nucl Med Biol. 2014;2(2):87–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kairemo K, Rasulova N, Partanen K, et al. Preliminary clinical experience of trans-1-Amino-3-(18)F-fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic Acid (anti-(18)F-FACBC) PET/CT imaging in prostate cancer patients. BioMed research international. 2014;2014:305182. doi: 10.1155/2014/305182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Suzuki H, Inoue Y, Fujimoto H, et al. Diagnostic performance and safety of NMK36 (trans-1-amino-3-[18F]fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid)-PET/CT in primary prostate cancer: multicenter Phase IIb clinical trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyv181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schuster DM, Taleghani PA, Nieh PT, et al. Characterization of primary prostate carcinoma by anti-1-amino-2-[(18)F]-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (anti-3-[(18)F] FACBC) uptake. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;3(1):85–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fei B, Schuster DM, Master V, et al. A Molecular Image-directed, 3D Ultrasound-guided Biopsy System for the Prostate. Proceedings of SPIE 2012; 2012; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. [Last accessed 1/15/16]; http://www.blueearthdiagnostics.com/news/fda-acceptance-of-nda-filing/

- 103.Mansi R, Fleischmann A, Macke HR, et al. Targeting GRPR in urological cancers--from basic research to clinical application. Nature reviews Urology. 2013;10(4):235–44. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2013.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dijkgraaf I, Franssen GM, McBride WJ, et al. PET of tumors expressing gastrin-releasing peptide receptor with an 18F-labeled bombesin analog. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(6):947–52. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.100891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chatalic KL, Franssen GM, van Weerden WM, et al. Preclinical comparison of Al18F- and 68Ga-labeled gastrin-releasing peptide receptor antagonists for PET imaging of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(12):2050–6. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.141143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kahkonen E, Jambor I, Kemppainen J, et al. In vivo imaging of prostate cancer using [68Ga]-labeled bombesin analog BAY86-7548. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(19):5434–43. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]