Abstract

Background

The Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele and stroke increase the risk of cognitive decline. However, the association of the APOE ε4 allele before and after stroke is not well understood.

Methods

Using a prospective sample of 3,444 (66% African Americans, 61% females, mean age = 71.9 years) participants, we examined cognitive decline relative to stroke among those with and without the APOE ε4 allele.

Results

In our sample, 505 (15%) had incident stroke. Among participants without stroke, the ε4 allele was associated with increased cognitive decline compared to non-carriers (0.080 vs. 0.036-units/year; p<0.0001). Among participants without the ε4 allele, cognitive decline increased significantly after stroke compared to before stroke (0.115 vs. 0.039-units/year; p<0.0001). Interestingly, cognitive decline before and after stroke was not significantly different among those with the ε4 allele (0.091 vs. 0.102-units/year; p=0.32). Poor cognitive function was associated with higher risk of stroke (HR=1.41, 95% CI=1.25–1.58), but the APOE ε4 allele was not (p=0.66). The APOE ε4 allele, cognitive function, and incident stroke were associated with mortality.

Conclusions

The association of stroke with cognitive decline appears to differ by the presence of the APOE ε4 allele, but no such interaction was observed for mortality.

Keywords: Cognitive Decline, APOE, Stroke, Mortality

INTRODUCTION

Accumulating evidence suggests that dementia is largely attributed to mixed vascular and neurodegenerative pathologies.1 Specifically, stroke is a major risk factor for cognitive impairment that may lead to vascular dementia,2-4 which also increases the risk of mortality.5-7 However, about 10% of patients experience a stroke event after dementia.8 This increased risk is also observed among participants with poor cognitive function.9

The Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele in old age is associated with an increased accumulation of beta amyloid10-11 that leads to greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.12-18 Some studies have investigated the association of the APOE ε4 allele with dementia as a consequence of stroke.2,19-20 Having one or more copies of the APOE ε4 allele increased the risk of dementia among participants with no history of stroke. However, the risk of dementia did not increase with the occurrence of stroke.2 The risk of dementia was higher among those with stroke and without the APOE ε4 allele.19 However, this risk did not increase with the APOE ε4 allele.20 In a genome-wide association study, a weak association was found between the APOE ε4 allele and stroke,21 and at least one study showed an association with cerebral infarcts, the pathologic substrate of clinical stroke.22 The APOE ε4 allele also increased the risk of mortality.23-25 However, it is not clear whether cognitive function and stroke may explain this risk.

The APOE ε4 allele is associated with increased cognitive decline, and dementia may occur after stroke. Hence, it is important to understand the interplay of APOE ε4 allele and stroke on cognitive decline and mortality. The goal of this paper is to examine the following research questions – (1) whether the increase in cognitive decline before and after stroke is similar between participants with and without the APOE ε4 allele, (2) if the APOE ε4 allele is associated with incident stroke after adjusting for cognitive function (3) whether the APOE ε4 allele is associated with mortality after adjusting for cognitive function and stroke.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

The CHAP study was performed using a door-to-door census of four neighborhoods in south side of Chicago during 1993 – 2012. Genotyping was performed on a sample of participants described previously in greater detail.26 Cognitive function tests were conducted during in-home interviews in approximately three-year cycles. A total of 4,807 participants were genotyped and eligible for this investigation. Of the 4,807 participants, 668 were excluded for incomplete Medicare coverage, 337 had a single cognitive assessment, 347 had stroke at baseline, and 11 had missing health or demographic variables and excluded from our study. This resulted in an analytical sample of 3,444 participants.

Participants excluded for a single cognitive assessment or prevalent stroke had significantly lower baseline cognitive function than participants included in the study (p<0.0001). However, we found no significant difference in baseline cognitive function between participants with incomplete Medicare coverage and our analytic sample (p=0.48).

Cognitive Function

We created a composite cognitive function test score based on a short battery of four tests that included two tests of episodic memory (Immediate and Delayed Recall Story) derived from the East Boston Test;27-28 one test of perceptual speed (Symbol Digits Modalities Test)29 and another test of general orientation and global cognition (Mini-Mental State Examination).30 The composite cognitive function test score was created by averaging the four tests after centering and scaling each to their baseline mean and standard deviation. This construct explains about 75% variation in the individual cognitive test scores and has shown good validity and reliability.31 Change in composite test scores can be interpreted as the change in standard deviation units relative to the baseline assessment of the study cohort.

Mortality

Mortality was ascertained by field reports from study interviewers. Following field reports of death, personal identifiers were matched with the Social Security Administration Death Master File (SSDMF). Once the match was made, personal identifiers were then linked to the National Death Index (NDI) for uniform ascertainment and nosology. In our sample, uniform ascertainment and verification of mortality using NDI was completed through 12/31/2010. Of the 1,457 deceased participants, NDI reports were confirmed for 1,274 (87%) participants; an additional 132 (9%) participants have been identified as deceased between 1/1/2011 to 9/12/2012, but are waiting to be confirmed following a forthcoming updated NDI database. The remaining 51 (4%) unconfirmed deaths were reported either during in-home visits or in Medicare records but could not be confirmed from NDI due to a lack of personal identifiers.

Stroke Hospitalizations

All CHAP participants were aged 65 years or older, and most participants had coverage through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). When participants were actively involved in a health maintenance organization (HMO), they were excluded from our analysis, since they would not simultaneously be enrolled in Medicare during those periods. In this study, participants were enrolled in Medicare 86% of the time and in an HMO 14% of the time. Prevalent stroke cases were ascertained at baseline using stroke hospitalization data as well as the self-reported question “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse or therapist that you had a stroke or brain hemorrhage?” with “Yes” and “Suspect or possible” as a positive response in 347 participants, who were excluded from our analysis. For this study, we coded two types of strokes, ischemic strokes identified by ICD-9 codes 433.01, 433.1, 433.2, 433.21, 433.3, 433.31, 433.81, 434.01, 434.1, 434.11, 434.91, 435.2, 435.3, 435.8, 435.9, 436.0, 437.1, 437.7, 437.9, and 438.0, and hemorrhagic strokes identified by ICD-9 codes 430, 431, 432.1, and 432.9. These codes were validated by co-author (NTA), who is a board-certified neurologist and CHAP investigator.32 A validity study was performed by comparing MRI data available in a subsample of our population with the stroke hospitalization data. In this subsample, participants with a stroke diagnosis also had one or more infarcts on about 90% of cases. About 18% of participants with no stroke diagnosis had one or more infarcts on MRI – most were small infarcts, suggesting that subclinical cerebrovascular disease was present that did not amount to a stroke hospitalization.

Apolipoprotein E ε4 Allele

The APOE genotypes were ascertained using two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs): rs7412 and rs429358 using the methods described by Hixson and Vernier33 based on the primers described by Wenham et al.34 These SNPs were genotyped in each subject using the Sequenom hME MassARRAY® platform. The genotyping success rate was nearly 100% for both the SNPs, which were also in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. In this study, 1034 (30%) participants had one copy of the APOE ε4 allele and 122 (4%) had two copies of the APOE ε4 allele. In previous studies, the APOE ε4 allele was associated with higher risk for AD and cognitive decline.14, 35-36 Due to the small sample size in ε4 homozygote, we combined ε4 homozygote with heterozygote.

Health and Demographic Variables

Our analysis adjusted for demographic variables, including age (centered at 75 years), sex (males or females), race (African Americans or non-Hispanic Whites), and education (measured in number of years of schooling completed and centered at 12 years). These covariates were selected since they may modify the association between cognitive decline and APOE ε4 allele status. For stroke and mortality risk models, we adjusted for health and lifestyle measures, including body mass index (kg/m2), heart disease, diabetes, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, smoking status (former smoker and current smokers vs. never smoker), physical activities (total minutes of walking, jogging, yard work, dancing, calisthenics or general exercise) and daily alcohol consumption (grams of alcohol per day) in addition to demographic variables.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed using means, standard deviations for continuous variables, and percentages for categorical variables. We also compared participant characteristics by the APOE ε4 allele using two-sample independent t-tests and chi-square tests depending on the measurement type. We modeled cognitive decline and mortality using a joint modeling framework with a longitudinal model for cognitive decline and a time-to-event model for mortality.37 The longitudinal model for cognitive decline was based on a linear spline with time of stroke hospitalization as a change point to examine cognitive decline before and after incident stroke within a random effects model.38 This was accomplished by creating a new time measure – difference in time between incident stroke hospitalization and time at assessments after incident stroke. Among participants with no incident stroke, this measure would be zero. A linear contrast was used to combine the additive components of pre-stroke cognitive decline and relative increase in post-stroke cognitive decline to provide an estimate of the absolute change in post-stroke cognitive decline. Random effects were included for the intercept and slopes. Given that 31% of participants with incident stroke died during the observation period, it was imperative that we accounted for mortality using a time-to-event model to account for truncation by estimating the parameters of the longitudinal model and time-to-mortality model within a shared parameter model framework. In addition, we used time-dependent Cox models to examine the association of the APOE ε4 allele with incident stroke while adjusting for cognitive function assessments prior to incident stroke. Joint models were fitted using JM library and time-dependent Cox models using survival library in R program.39

RESULTS

Population Characteristics

Demographic and health characteristics of the sample by the APOE ε4 allele are shown in Table 1. Participants were 66% African Americans and 61% females with an average age of 71.9 years, and education of 12.6 years.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 3444 Participants Stratified by the APOE ε4 Allele Status

| All participants Mean (SD) N=3444 |

No copies of ε4 Mean (SD) N=2288 |

≥1 copy of ε4 Mean (SD) N=1156 |

p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.9 (6.2) | 72.2 (6.4) | 71.3 (5.7) | <0.0001 |

| Education (years) | 12.6 (3.4) | 12.6 (3.4) | 12.7 (3.4) | 0.51 |

| Cognitive function (sd units) | 0.368 (0.658) | 0.390 (0.638) | 0.325 (0.694) | 0.006 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.3 (6.0) | 28.2 (5.9) | 28.5 (6.0) | 0.27 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 138.1 (18.8) | 138.1 (18.9) | 138.1 (18.6) | 0.98 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 78.0 (10.8) | 77.8 (10.4) | 78.4 (11.5) | 0.13 |

| Physical activity (hrs/week) | 3.1 (5.1) | 3.3 (5.4) | 2.9 (4.6) | 0.22 |

| Alcohol consumption (gms/week) |

0.45 (1.15) | 0.46 (1.16) | 0.43 (1.12) | 0.36 |

| Age at stroke (years) | 80.6 (7.3) | 81.1 (7.4) | 79.9 (7.0) | 0.10 |

| Age at death (years) | 85.7 (6.8) | 86.2 (7.0) | 84.6 (6.5) | <0.0001 |

| Females, % | 2101, 61% | 1424, 62% | 677, 59% | 0.03 |

| African Americans, % | 2269, 66% | 1429, 62% | 840, 73% | <0.0001 |

| Heart disease, % | 367, 11% | 257, 11% | 110, 10% | 0.12 |

| Diabetes, % | 221, 6% | 152, 7% | 69, 6% | 0.44 |

| Stroke, % | 505, 15% | 341, 15% | 164, 14% | 0.60 |

| Former smoker, % | 1327, 38% | 864, 38% | 463, 40% | 0.20 |

| Current smoker, % | 456, 13% | 301, 13% | 155, 13% | 0.84 |

| Deceased, % | 1457, 42% | 973, 43% | 484, 42% | 0.69 |

p-values are based on two-sample independent t-tests for continuous measures and chi-square test statistic for categorical measures comparing participants with no copies to ≥1 copy of ε4 allele

During follow-up, 505 (15%) participants were hospitalized for stroke. The average follow-up time was 9.8 years for those with stroke and 9.4 years for those without stroke. Of the 505 participants with incident stroke, 156 (31%) had died without a follow-up, thereby only contributing to mortality risk model. Also, baseline cognitive function was lower among participants who died without a follow-up compared to participants who had one or more follow-ups (0.176 vs. 0.277; p=0.001). The average follow-up time was 4.5 years after stroke hospitalization. We found no significant difference in follow-up time after stroke by the APOE ε4 allele. Participants with the APOE ε4 allele had a lower baseline cognitive function than those without the APOE ε4 allele.

Association of Cognitive Function and the APOE ε4 Allele with Incident Stroke

Table 2 shows the risk of time-to-incident stroke in terms of cognitive function, the APOE ε4 allele, and demographic, health, and lifestyle measures. Poor cognitive function was associated with an increased risk of incident stroke (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.41, 95% CI= 1.25–1.58). However, the APOE ε4 allele was not associated with incident stroke (HR = 1.04, 95% CI= 0.86–1.26). Older age, systolic blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, and current smoking status were also associated with an increased risk of incident stroke.

Table 2.

Hazard Ratio (HR) and Confidence Interval (CI) for Risk of Incident Stroke Among 3444 Participants from a Sample of African Americans and Whites Aged 65 and Older

| Risk of Incident Stroke | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Cognitive function | 1.41 | 1.25, 1.58 | <0.0001 |

| APOE ε4 allele | 1.04 | 0.86, 1.26 | 0.66 |

| Age | 1.05 | 1.03, 1.07 | <0.0001 |

| Males | 1.11 | 0.92, 1.34 | 0.28 |

| Education | 1.00 | 0.97, 1.03 | 0.89 |

| African Americans | 0.94 | 0.76, 1.16 | 0.57 |

| Systolic BP | 1.09 | 1.04, 1.14 | 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP | 0.93 | 0.85, 1.02 | 0.13 |

| Heart disease | 1.53 | 1.20, 1.95 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 2.01 | 1.50, 2.71 | <0.0001 |

| Former smoker | 0.98 | 0.80, 1.19 | 0.85 |

| Current smoker | 1.61 | 1.20, 2.14 | 0.001 |

| Body mass index | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.01 | 0.87 |

| Physical activity | 0.99 | 0.97, 1.01 | 0.51 |

| Alcohol consumption | 1.01 | 0.92, 1.10 | 0.84 |

Association of the APOE ε4 Allele and Incident Stroke with Cognitive Decline

The annual change in cognitive function by incident stroke and the presence of the APOE ε4 allele is shown in Table 3. Among participants without stroke, the presence of the APOE ε4 allele was associated with increased cognitive decline compared to those without the APOE ε4 allele (0.039-units/year vs. 0.080-units/year), a 2.2 fold (95% CI= 2.0–2.4; p<0.0001) faster cognitive decline.

Table 3.

Annual Change in Cognitive Function Among Participants Free of Stroke, and Before and After Incident Stroke by the APOE ε4 Allele

| No copies of ε4 | ≥1 copy of ε4 | |

|---|---|---|

| Free of Stroke | ||

| Cognitive Decline - Free of Stroke | 0.036 (.002) | 0.080 (.006) |

|

| ||

| Incident Stroke | ||

| Cognitive Decline Before Stroke | 0.039 (.010) | 0.091 (.019) |

| Cognitive Decline After Stroke | 0.115 (.014) | 0.102 (.022) |

NOTE: Values shown are estimates (standard error) of change in cognitive function in (standard deviation units per year) after adjusting for main effects of age, male sex, education, and race, and interaction of time before stroke and time after stroke with age, male sex, education, and race.

Among participants with incident stroke and no copies of the APOE ε4 allele, cognitive decline before incident stroke was 0.039-units/year among, which increased to 0.115-units/year following incident stroke. Therefore, cognitive decline was roughly 2.3-fold faster following incident stroke among participants with no copies of the APOE ε4 allele (p<0.0001). This increase was similar to the increase observed due to the APOE ε4 allele among participants free of stroke.

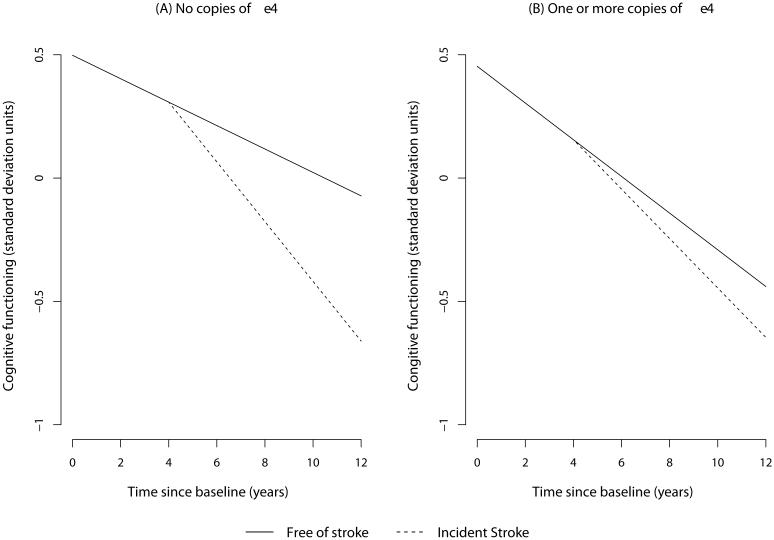

Among participants with incident stroke and one or more copies of the APOE ε4 allele, cognitive decline before incident stroke was 0.091-units/year, which showed a small but non-significant increase to 0.102-units/year (p=0.26). Therefore, incident stroke did not increase the rate of cognitive decline among participants with one or more copies of the APOE ε4 allele. The 10-year course of cognitive decline before and after incident stroke among participants with and without the APOE ε4 allele is shown in Figure 1(A) and Figure 1(B), respectively.

Figure 1. Annual Change in Cognitive Function before and after Incident Stroke at 4th Year of Observation by the APOE ε4 Allele.

Annual change in cognitive trajectories is depicted for those free of stroke and with incident stroke at year 4 among those with no APOE ε4 allele and those with the APOE ε4 allele using regression coefficients from the longitudinal cognitive decline model.

From our regression models, age and education were associated with cognitive decline after incident stroke among those without the APOE ε4 allele (data not shown). However, demographic variables were not associated with cognitive decline among those with the APOE ε4 allele. A test for racial differences in the association of cognitive decline and APOE ε4 allele was not significant (p=0.74).

Association of Cognitive Function, Stroke, and the APOE ε4 Allele with Mortality

Poor cognitive function was associated with a higher risk of mortality (HR= 2.04, 95% CI= 1.89–2.19) (Table 4). The APOE ε4 allele (HR=1.16, 95% CI= 1.03–1.30) and incident stroke (HR= 1.26, 95% CI= 1.10–1.43) were also associated with higher risk of mortality. In a separate model, a two-way interaction of the APOE ε4 allele and incident stroke on mortality was not significant (p=0.53). A significant interaction of age with cognitive function (p=0.012) and incident stroke (p=0.032) on increased mortality risk was also observed, suggesting that age played an important role in mortality risk (data not shown).

Table 4.

Hazard Ratio (HR) and Confidence Interval (CI) for Risk of Mortality among 3444 African American and White Participants from a Population Sample

| Mortality Risk | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Cognitive function | 2.04 | 1.89, 2.19 | <0.0001 |

| APOE ε4 allele | 1.16 | 1.03, 1.30 | 0.017 |

| Stroke | 1.26 | 1.10, 1.43 | 0.0004 |

| Age | 1.12 | 1.11, 1.13 | <0.0001 |

| Males | 1.41 | 1.25, 1.58 | <0.0001 |

| Education | 1.02 | 1.00, 1.04 | 0.069 |

| African Americans | 0.65 | 0.55, 0.75 | <0.0001 |

| Systolic BP | 1.03 | 0.99, 1.06 | 0.10 |

| Diastolic BP | 0.95 | 0.90, 1.00 | 0.06 |

| Heart disease | 1.23 | 1.06, 1.43 | 0.008 |

| Diabetes | 2.00 | 1.65, 2.43 | <0.0001 |

| Former smoker | 1.20 | 1.06, 1.35 | 0.002 |

| Current smoker | 1.58 | 1.34, 1.87 | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.02 | 0.59 |

| Physical activity | 0.97 | 0.96, 0.98 | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.99 | 0.94, 1.04 | 0.59 |

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that the APOE ε4 allele was not associated with incident stroke in old age. However, poor cognitive function was associated with incident stroke. Although the presence of the APOE ε4 allele was associated with faster cognitive decline, incident stroke did not increase cognitive decline among participants with the ε4 allele. Additionally, incident stroke increased cognitive decline by over 2-fold among participants without the ε4 allele. These findings suggest that the association of incident stroke and cognitive decline is different by the presence of the APOE ε4 allele. Poor cognitive function, the APOE ε4 allele, and stroke all contributed to increased risk of mortality.

Increased cognitive decline before incident stroke suggests subclinical or silent cerebrovascular disease, which may result in incident stroke irrespective of the presence of the APOE ε4 allele. Participants probably had low cognitive reserve and greater cognitive impairment resulting in a non-significant association with cognitive decline among those with the APOE ε4 allele. However, participants without the APOE ε4 allele had incident stroke from risk factors that were not associated with cognitive decline. Hence, our findings suggest that these participants had a pattern of cognitive decline before stroke that was similar to those without stroke. After incident stroke, participants showed increased cognitive decline that was slightly higher than those with the APOE ε4 allele. Additional MRI-based studies to assess the presence of subcortical or lacunar infarcts, or microhemorrages and their association to cognitive function are needed to examine these possibilities in greater detail.

Poor cognitive function may be indicative of pre-existing subclinical cerebrovascular disease, which may explain why cognitive function was associated with an increased risk of stroke,9 while the APOE ε4 allele was not associated with stroke. An earlier meta-analysis that did not adjust for cognitive function found a marginal association of the APOE ε4 allele with ischemic stroke.21 Our population-based study found that the APOE ε4 allele was not associated stroke after adjusting for cognitive function.

The APOE ε4 allele and stroke increased mortality risk even after controlling for other known risk factors. Interestingly, even after adjusting for known health and biological risk factors, poor cognitive function was still associated with mortality risk. Further studies examining the possible genetic pathways of the APOE ε4 allele, cognition, and vascular disease might provide a better understanding of mortality risk in old age.

The primary strengths of this study are the prospective study design with uniform ascertainment of biological, lifestyle and health characteristics, and cognitive function. Participants were drawn from a large geographically defined biracial population, making it likely that a broad spectrum of participants and paths of cognitive changes were represented. Cognitive function was assessed using four validated scales and measured on more than two occasions among those at risk of incident stroke. Almost 57% of older adults died during the follow-up period leading to informative censoring as well as providing sufficient power to detect robust mortality-adjusted findings. Cognitive decline and stroke both uniquely contribute to neurological and cerebrovascular health with independent and overlapping etiologies in the aging process. The APOE ε4 allele was directly genotyped in a large population-based sample of 3444, which is a much larger sample than previous studies that have reported the association of incident dementia and stroke relative to the APOE ε4 allele.

Several limitations of our study also need to be addressed. One of the main limitations of this study is the assessment of incident stroke using Medicare data with external validation in a much smaller sample. As such, minor or silent stroke events could not be accounted for in our investigation. It is likely that the study included participants who had stroke but were not characterized as such in Medicare records. Also, participants may be incorrectly coded as having stroke hospitalization or other insurance coverage not reported to the Medicare database. These misclassification errors may alter the sizes of our cognitive decline estimates. Even though time-of-stroke was collected from actual Medicare dates, cognitive assessments around this time may be at a maximum of 3 years away. Therefore, any short-term changes following stroke may be difficult to ascertain.

Additionally, about 31% of participants did not provide cognitive assessments after incident stroke. Although these participants had a lower baseline cognitive function, their cognitive decline before stroke was similar to those who provided follow-up data. Even though no race differences between African Americans and Whites were observed for cognitive decline before and after incident stroke among APOE carriers, and given the small number of stroke events, our ability to detect these changes may be limited. Cardiovascular disease markers may also modify the association of APOE ε4 allele with incident stroke and cognitive decline. However, our sample is not large enough to reliably test these moderating effects.

The APOE ε4 allele was not associated with stroke but was associated with mortality and more rapid cognitive decline before incident stroke. However, incident stroke was associated with faster cognitive decline that was more severe in participants without the APOE ε4 allele. The trajectory of cognitive decline after stroke had minor changes among participants with the APOE ε4 allele suggesting two possibilities. First, that this subgroup of participants was not severely affected by an incident stroke event, or secondly that the group that had the worst decline was already deceased. As such, understanding the role of the APOE ε4 allele and stroke on cognitive decline and mortality might help us better understand the underlying disease mechanism and create better preventive strategies.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes for Health (R01-AG051635, R01-AG09966 and R01-AG030146). Dr. Everson-Rose was supported in part by grant (1P60MD003422) from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) and by the Program in Health Disparities Research and the Applied Clinical Research Program at the University of Minnesota. Contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, NIA or NIMHD.

REFERENCES

- 1.James BD, Bennett DA, Boyle PA, et al. Dementia from Alzheimer disease and mixed pathologies in the oldest old. JAMA. 307:1798–1800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savva GM, Stephan BCM, Alzheimer’s Society Vascular Dementia Systematic Review Group Epidemiological Studies of the Effect of Stroke on Incident Dementia: A Systematic Review. Stroke. 2010;41:e41–e46. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.559880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vinters HV, Ellis WG, Zarow C, et al. Neuropathologic substrates of ischemic vascular dementia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:931–945. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.11.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewey ME, Saz P. Dementia. cognitive impairment and mortality in persons aged 65 and over living in the community: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:751–761. doi: 10.1002/gps.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gale CR, Martyn CN. Cooper C. Cognitive impairment and mortality in a cohort of elderly people. BMJ. 1996;312:608–611. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7031.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neale R, Brayne C, Johnson AL. Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Writing Committee. Cognition and survival: an exploration in a large multicentre study of the population aged 65 years and over. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1383–1388. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.6.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pendlebury ST, Rothwell PM. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajan KB, Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS, et al. Association of cognitive function, incident stroke, and mortality. Stroke. 2014;45:2563–2567. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deane R, Sagare A, Hamm K, et al. APOE isoform-specific disruption of amyloid beta peptide clearance from mouse brain. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:4002–4013. doi: 10.1172/JCI36663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strittmatter WJ, Saunders AM, Schmechel D, et al. Apolipoprotein E: high-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:1977–1981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saunders, Strittmatter WJ, Schemchel D. Association of Apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1993;43:1467–1472. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer’s disease. JAMA. 1997;278:1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knopman DS, Mosley TH, Catellier DJ, et al. Fourteen-year longitudinal study of vascular risk factors, APOE genotype, and cognition: the ARIC MRI Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bretsky P, Guralnik JM, Launer L, et al. The role of APOE-epsilon4 in longitudinal cognitive decline: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Neurology. 2003;60:1077–1081. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055875.26908.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Packard C, Westendorp R, Stott D, et al. Association between apolipoprotein E4 and cognitive decline in elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1777–1785. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Rishc NJ, et al. Protective effect of apolipoprotein E type 2 allele for late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 1994;7:180–184. doi: 10.1038/ng0694-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chartier-Harlin MC, Parfitt M, Legrain S, et al. Apolipoprotein E4 allele as a major risk factor for sporadic early and late-onset form of Alzheimer's disease: analysis of the 19q1 3-2 chromosomal region. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:569–574. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin YP, Østbye T, Feightner JW, et al. Joint effect of stroke and APOE E4 on dementia risk: the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Neurology. 2008;70:9–16. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000284609.77385.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivan CS, Seshadri S, Beiser A, et al. Dementia after stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 2004;35:1264–1268. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000127810.92616.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sudlow C, González NAM, Kim J, Clark C. Does Apolipoprotein E genotype influence the risk of ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, or subarachnoid hemorrhage? Stroke. 2006;37:364–370. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000199065.12908.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider JA, Bienias JL, Wilson RS, et al. The Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele increases the odds of chronic cerebral infarction detected at autopsy in older persons. Stroke. 2005;36:954–959. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000160747.27470.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beekman M, Blanche H, Perola M, et al. Genome-wide linkage analysis for human longevity: Genetics of healthy aging study. Aging Cell. 2013;12:184–193. doi: 10.1111/acel.12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deelen J, Beekman M, Uh HW, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a single major locus contributing to survival into old age; the APOE locus revisited. Aging Cell. 2011;10:686–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00705.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nebel A, Kleindorp R, Caliebe A, et al. A genome-wide association study confirms APOE as the major gene influencing survival in long-lived individuals. Mech Ageing Dev. 2011;132:324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajan KB, Wilson RS, Skarupski K, et al. Gene-behavior interaction of APOE ε4 allele and depressive symptoms on cognitive decline. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:101–108. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albert M, Smith LA, Scherr PA, et al. Use of brief cognitive tests to identify individuals in the community with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease. Int J of Neurosci. 1991;57:167–178. doi: 10.3109/00207459109150691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson RS, Bennette DA, Bienias JL, et al. Cognitive activity and incident AD in a population-based sample of older adults. Neurology. 2002;59:1910–1914. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000036905.59156.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith A. Symbol Digits Modalities Test. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh TR. “Mini-Mental State”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson RS, Benette DA, Beckett LA, et al. Cognitive activity in older persons from a geographically defined population. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999;54:155–160. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.3.p155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson KM, Clark CJ, Lewis TT, et al. Psychosocial distress and stroke risk in older adults. Stroke. 2013;44:367–372. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.679159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hixson J, Vernier DO. Restriction isotyping of human Apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with Hhal. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenham PR, Price WH, Blundell G. Apolipoprotein E genotyping by one-stage PCR. Lancet. 1991;337:1158–1159. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92823-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Packard CJ, Westendorp RG, Stott DJ, et al. Association between apolipoprotein E4 and cognitive decline in elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1777–1785. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bretsky P, Guralnik JM, Launer L, et al. The role of APOE-epsilon4 in longitudinal cognitive decline: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Neurology. 2003;60:1077–1081. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055875.26908.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diggle PJ, Heagerty PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rizopoulos D. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2012. Joint models for longitudinal and time-to-event data. [Google Scholar]

- 39.R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Version 2.15.2. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2010. [Google Scholar]