Abstract

Background

We evaluated impact of radiation, reconstruction and timing of tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP) on complications and speech outcomes.

Methods

Retrospective review identified 145 TEP patients between 2003–2007.

Results

Ninety-nine patients (68%) had primary and 46 (32%) secondary TEP, with complications occurring in 65% and 61% respectively (p=0.96). Twenty-nine patients (20%) had major complications (18 primary; 11 secondary, p=0.42). Ninety-four patients (65%) had pre-TEP radiation, 39 (27%) post-TEP radiation, and 12 (8%) no radiation. With patients grouped by TEP timing and radiation history, there was no difference in complications, fluency, or TEP use. With mean 4.7-year follow up, 82% primary and 85% secondary used TEP for primary communication (p=0.66). Free-flap patients used TEP more commonly for primary communication after secondary versus primary TEP (90% v 50%, p=0.02).

Conclusions

Primary and secondary tracheoesophageal speakers experience similar high rates of complications. Extent of pharyngeal reconstruction, rather than radiation, may be more important in selection of TEP timing.

Keywords: TEP, tracheoesophageal puncture, tracheoesophageal prosthesis, complications, speech outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Since the first total laryngectomy in 1873 by Billroth, restoration of alaryngeal speech has been a post-operative priority. In fact, 80% of laryngectomees rate communication as their most important quality of life concern1. The three most common methods for alaryngeal speech production after laryngectomy remain esophageal speech, use of an electrolarynx, and tracheoesophageal voice restoration that depends on the placement of a one-way valved prosthesis through a surgically created tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP). Among these options, tracheoesophageal voice restoration has been associated with the best speech quality and it is relatively safe, and has therefore become the preferred method for speech rehabilitation2. Blom and Singer first described the current method of TEP with insertion of a one-way valve prosthesis in 1980 as a secondary procedure after the patient recovered from their surgery3. Numerous studies have since shown that performing TEP as a primary procedure at the time of total laryngectomy is safe and affords faster acquisition of speech compared with secondary TEP2, 4–9. Other advantages of primary TEP include avoiding a second procedure and the potential to use the TEP site for enteral feeding access perioperatively. Because of this, primary TEP has become the procedure of choice in many contemporary practices2, 5.

Reports of tracheoesophageal speech success and the occurrence of complications are not always clear. Many retrospective studies demonstrate similar complication rates between primary and secondary TEP while others show increased major complication rates among patients receiving secondary TEP2,4–9,11,12. However, the comparison of primary to secondary TEP is often confounded by patient selection, as many clinicians choose to delay the TEP procedure in patients with extended pharyngeal reconstruction and/or a history of radiation therapy. Additionally, some retrospective studies have shown no increased risk of complications associated with primary TEP in patients who have received previous radiation13–19. Therefore, no consensus currently exists regarding the strict indications for secondary TEP in salvage laryngectomy patients. Some surgeons still consider previous radiation as a contraindication for primary TEP, particularly for patients who require laryngopharyngeal resection and reconstruction2,20. Furthermore, many studies have lacked sufficient power to address the question of previous radiation and its influence on the rate of post-operative complications in primary TEP. Herein, a large cohort of patients consecutively undergoing primary or secondary TEP were examined to determine the impact of radiation and pharyngeal reconstruction on speech outcomes and complications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After approval by the institutional review board, a retrospective chart review was conducted of all patients undergoing TEP between 2003–2007 at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. All patients undergoing TEP as a primary procedure or secondary procedure (in the operating room or in clinic) were included.

Institutional TEP Management

TEP candidacy is assessed in all patients scheduled for total laryngectomy jointly by the multidisciplinary team, primarily the head and neck surgeon, plastic surgeon and speech language pathologist. Selection criteria in determination of TEP candidacy and determination of primary versus secondary TEP include the extent of radiotherapy toxicity, the extent of planned resection and necessary reconstruction, and psychosocial considerations which influence patients’ ability to return for necessary follow up and perform lifelong care for an exchangeable prosthesis21. Both primary and secondary TEP are performed at this institution. A red rubber catheter (12–14-French) is used to stent the TEP in the immediate postoperative setting. A voice prosthesis is first placed 7–10 days postoperatively after primary TEP and 3–5 days postoperatively after secondary TEP. A variety of indwelling and non-indwelling TE voice prostheses are used within the institution (InHealth Technologies, Carpinteria, CA; Atos Medical, Hörby, Sweden). MD Anderson TEP Tracking Database was queried and retrospective review of the electronic medical record conducted for TEP outcomes. Prosthetic variables, complications, communication method, and TE speech fluency were captured prospectively on a standardized form by speech pathologists in the TEP Tracking Database during routine clinic visits. TE speech fluency was graded per Lewin et al as fluent (ability to produce greater than 10 seconds of continuous sound production and 10–15 syllables per breath), non-fluent, or non-speaker (sound production less than one second and absent word production)22. Complications were classified by standard definitions. Enlarged TEP was defined as leakage around the prosthesis unresponsive to standard prosthetic management. Pharyngoesophageal spasm was diagnosed only with radiographic confirmation. Frequent leakage through the voice prosthesis was only coded when two or more consecutive prostheses lasted four weeks or less due to leakage. Stomal stenosis was diagnosed for all patients with stenosis sufficient to warrant dilation with a laryngectomy tube. Patient demographic data was collected along with disease-specific information, type of surgery and reconstruction, adjunctive therapies such as chemotherapy and radiation, TEP timing, post-operative complications, and speech outcomes.

Complications were further classified as those directly related to the TE puncture or prosthesis or indirectly related to the TE puncture or prosthesis but with the potential to significantly affect TEP use or speech fluency. Direct complications included enlarged TEP, aspiration of the prosthesis, pneumonia secondary to leakage, spontaneous closure of TEP, partial tracheoesophageal tract closure, granulation tissue, and superior tract migration. Indirect complications included pharyngocutaneous fistula, pharyngoesophageal spasm or stricture, lymphedema, and stomal stenosis. Complications were also subdivided into major and minor complications. Major complications included spontaneous closure of TEP, complications requiring surgical intervention or intentional closure of TEP, and pneumonia secondary to leakage while minor complications were defined as those which were managed conservatively and resolved without surgical intervention or TEP removal.

The data were analyzed using Statistica statistical software application (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, www.statsoft.com). Basic descriptive analysis of aggregate data was calculated including frequencies of study patients within the categories for each of the parameters of interest. Associations between parameters and endpoints was assessed by Pearson’s Chi-square test or, where there are fewer than ten subjects in any cell of a 2 × 2 grid, by the two-tailed Fisher exact test.

RESULTS

One hundred forty-five patients underwent TEP between 2003 and 2007. With this cohort, assuming alpha 0.05, there was 80% power to detect an effect size as small as 0.30 in this population. Patient demographics, tumor site, and type of surgical resection/reconstruction are summarized in Table I. Median age at TEP was 64 years (range 37–86 years). Ninety-nine patients had primary TEP (68%) and 46 (32%) had secondary TEP either in the operating room or in the clinic (Table I). Twenty-nine (20%) patients had free flap pharyngeal reconstruction. Most (65%) patients had a salvage laryngectomy after radiation therapy. Thirty-nine (27%) patients had radiation therapy post-operatively and 12 patients (8%) did not have radiation therapy. For patients who had radiation, median radiation dose was 60 Gray (range 30 – 78 gray). Of the patients who underwent radiation, 18 (14%) underwent intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), and the remaining 114 (86%) had conventional three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy. Thirty-nine patients (27%) underwent chemotherapy prior to TEP, 22 patients (15%) had chemotherapy post-operatively and 84 patients (58%) did not have chemotherapy. Mean and median follow-up times were 56 (standard deviation 37.6 months) and 53 months (range 1.4–156 months) respectively after the initial TEP procedure.

Table I.

Patient Characteristics

| Number (%) n=145 | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 120 (83) |

| Female | 25 (17) |

| Median Age at TEP | 64 (range 37–86) |

| Cancer site | |

| Larynx | 121 (83) |

| Hypopharynx | 12 (8) |

| Thyroid | 6 (4) |

| Oropharynx | 2 (1) |

| Other | 4 (3) |

| Cancer stage | |

| Primary advanced stage | 65 (45) |

| Recurrent | 80 (55) |

| Type of surgical resection | |

| Total laryngectomy | 108 (74) |

| Total laryngectomy with partial pharyngectomy | 27 (19) |

| Total laryngopharyngectomy | 7 (6) |

| Total laryngectomy with partial glossectomy | 3 (2) |

| Type of surgical laryngeal closure | |

| Vertical | 75 (52) |

| Horizontal | 27 (19) |

| ”T”-type | 11 (8) |

| Pedicled or free flap | 32 (22) |

| Type of surgical reconstruction | |

| Primary closure | 111 (77) |

| Pectoralis myocutaneous | 3 (2) |

| Anterolateral thigh free flap | 27 (19) |

| Radial forearm free flap | 3 (2) |

| Combination myocutaneous/free flap | 1 (1) |

| Tracheoesophageal puncture | |

| Primary | 99 (68) |

| Secondary | 46 (32) |

| Timing of Radiation therapy | |

| Pre-tracheoesophageal puncture | 94 (65) |

| Post-tracheoesophageal puncture | 39 (27) |

| None | 12 (8) |

| Type of Radiation | |

| Intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) | 18 (14) |

| Conventional three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy | 114 (86) |

| Timing of Chemotherapy | |

| Pre-tracheoesophageal puncture | 39 (27) |

| Post-tracheoesophageal puncture | 22 (15) |

| None | 84 (58) |

Complications

One hundred twenty (83%) patients had a post-operative complication (major or minor) including those that were directly related and those that were not related to the TEP (Table II). Eighty-nine (61%) patients had two or more complications. A majority of complications were minor and were managed conservatively (89%), while 13 patients (11%) had direct TEP-related complications that required surgery (including 7 patients with spontaneous closure who subsequently underwent re-puncture) (Table II). Ninety-one patients (63%) had a post-operative complication directly related to TEP, among which twenty-nine (20%) had major complications directly related to TEP. The breakdown of complications according to those directly and not directly related to the TEP and/or prosthesis is reported in Table II.

Table II.

Complications and Management

| Complication | Number (%) n=145 | Surgical management (%) | Conservative management (%) | Initial management strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications directly related to TE puncture/prosthesis | ||||

| Enlarged TE puncture | 20 (14) | 0 (0) | 20 (100) | Prosthetic management11,23,24, reflux treatment25 |

| Aspiration of TE prosthesis | 3 (2) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | Bronchoscopy and prosthetic replacement |

| Pneumonia secondary to leakage | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | Antibiotics |

| Spontaneous complete TE puncture closure | 11 (8)* | -- | -- | Tracheoesophageal re-puncture |

| Partial TE tract closure/stenosis | 24 (17) | 0 (0) | 24 (100) | Prosthetic resizing/replacement |

| Granulation tissue around TE puncture site | 21 (14) | 2 (10) | 19 (90) | Topical steroid, silver nitrate, prosthetic resizing/replacement |

| Superior tract migration | 15 (10) | 0 (0) | 15 (100) | Prosthetic management |

| Frequent leakage through TE prosthesis | 40 (28) | 1 (3) | 39 (98) | Swallow evaluation, prosthetic management |

| Complications not directly related to TE puncture/prosthesis | ||||

| Pharyngocutaneous fistula | 33 (23) | 11 (33) | 22 (67) | Antibiotics, local wound care26, 27 |

| Pharyngoesophageal spasm | 31 (21) | 0 (0) | 31 (100) | Fluoroscopy/EMG-guided botulinum toxin injection28, 29 |

| Stricture | 20 (14) | 3 (15)** | 17 (85) | Esophageal dilation30 |

| Lymphedema | 27 (19) | 0 (0) | 27 (100) | Complete decongestive therapy31 |

| Stomal stenosis | 56 (39) | 4 (7)*** | 52 (93) | Laryngectomy tube/button dilation32 |

7 of these patients subsequently had tracheoesophageal re-puncture

Pharyngeal reconstruction

Tracheostomaplasty33

The complications were assessed according to timing of TEP and radiation treatment, with patients divided into four distinct groups (Figure I). In multiple subgroup analyses, there was no significant difference in complications between primary TEP and secondary TEP and a history of radiation therapy prior to TEP (p>0.05).

Figure I.

Relative complication rates based on timing of TEP and radiation (XRT)

*No significant difference between complications in any group, all p > 0.05.

**Major complications included spontaneous or intentional TEP closures, complications requiring surgical intervention, and pneumonia secondary to leakage

***Direct complications included enlarged TEP, aspiration of prosthesis, pneumonia secondary to leakage, spontaneous or intentional closure of TEP, partial TE tract closure, granulation tissue and superior tract migration.

Free Flap Reconstruction

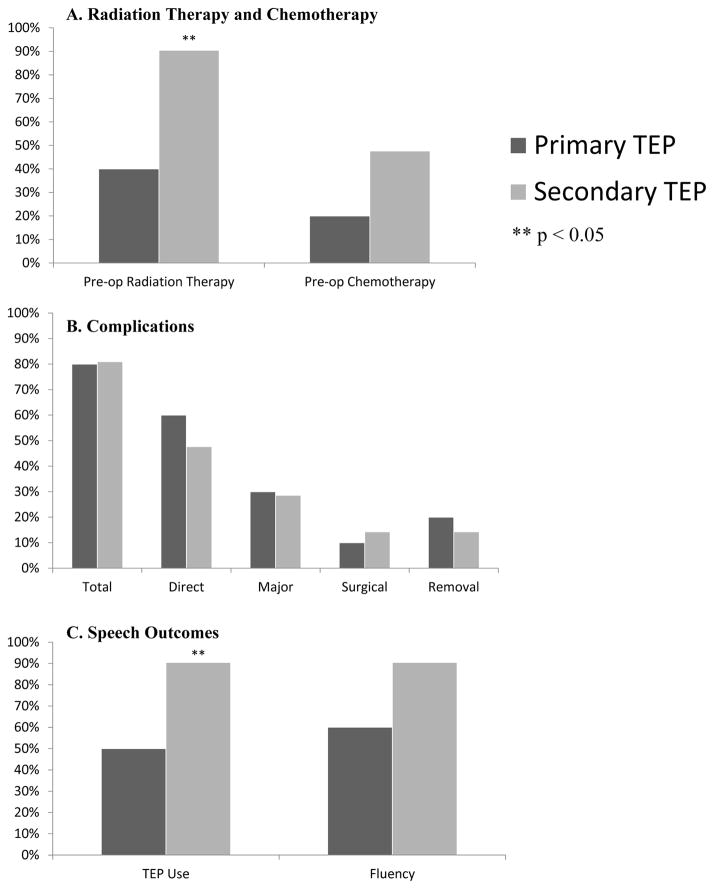

Thirty-one patients (21%) required free flap reconstruction of their laryngopharyngeal defect with radial forearm free flap (n=4) or anterolateral thigh (ALT) free flap (n=27). Ten (32% of free flap patients) of these had primary TEP. Significantly more patients who underwent free flap reconstruction with secondary TEP were using their TEP at last follow up compared with those who underwent primary TEP (50% users in primary vs 90% users in secondary, p=0.02). This trend persisted in speech fluency outcomes but was not statistically significant (60% fluent in primary vs 90% fluent in secondary, p=0.07). There was no significant difference in the rates of complication across any category between primary and secondary TEP in the free flap reconstruction subgroup (Figure II). Within the subgroup of patients undergoing free flap reconstruction, 4 patients (40%) with primary TEP had previous radiation and 19 patients (90%) with secondary TEP had previous radiation (p=0.01). No primary TEP patients in the free flap cohort had total laryngopharyngectomy with tubed free flap reconstruction, while 7 (33%) secondary TEP patients had total laryngopharyngectomy with tubed free flap reconstruction (p=0.07). There was no significant difference in age or history of chemotherapy between primary and secondary TEP groups in the free flap cohort.

Figure II.

Outcomes and complications in patients with free-flap reconstruction

Overall Speech Outcomes

In total, 120 (83%) patients were using their TEP for communication at last follow-up, or prior to any recurrence of cancer or closure of the TEP (Table III). Among all patients, there was no significant difference between primary and secondary TEP in terms of achievement of speech fluency (fluent vs non-fluent) or use of TEP as a primary mode of communication (Table IV).

Table III.

Speech outcomes

| Speech outcome | Number (n=145) | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary mode of communication | ||

| TE prosthesis | 120 | (83) |

| Other (Electrolarynx, writing, gestures) | 25 | (17) |

| Best fluency with TEP* | ||

| Fluent | 131 | (90) |

| Not Fluent | 14 | (10) |

Fluency as judged by speech language pathologist evaluating the patient at follow-up visits. If multiple follow up visits were included, the best recorded outcome was used for calculations.

Table IV.

Speech outcomes in relation to TEP timing and radiation

| TE Prosthesis User Ratio (%) n=145 | Fluency Ratio* (%) n=145 | |

|---|---|---|

| Timing of TE puncture | ||

| Primary | 81/99 (82) | 90/99 (91) |

| Secondary | 39/46 (85) | 41/46 (89) |

| Radiation | ||

| None | 12/12 (100) | 12/12 (100) |

| Pre-TE puncture | 79/94 (84) | 83/94 (88) |

| Post-TE puncture | 29/39 (74) | 36/39 (92) |

Fluency as judged by speech language pathologist evaluating the patient at follow-up visits. If multiple follow up visits were included, the best-recorded outcome was used.

There was also no significant difference in outcomes based on timing of radiation therapy (Table 4). All non-radiated patients were fluent and using their TEP as the primary mode of communication. There was no statistically significant difference in speech fluency and TEP use in non-radiated patients compared to radiated patients (p = 0.14 and 0.10, respectively).

TEP Removal

Twenty-five patients (17%) were not using their TEP at last follow-up. Among these 25 patients, 5 had intentional TEP removal due to either poor function or a complication and did not undergo re-puncture, 4 had spontaneous closure of the TEP without re-puncture, and 16 patients were not using their TEP for communication. There were a total of nine intentional TEP removals: five for poor function, two for complications, and two for both poor function and complications. Four of these nine TEP removals were subsequently re-punctured. The 16 patients who retained their TEP were not using it because of poor function and/or fluency. These TEPs were not removed in these particular patients due to a mature tract that was unable to close despite poor functional outcome. In these scenarios, dummy prostheses were placed to plug the tracheoesophageal tract to prevent aspiration.

DISCUSSION

In this large cohort of primary and secondary TEP patients with almost 5-year mean follow up, 83% of patients used their TEP for routine communication. In addition, 90% level of tracheoesophageal voice fluency was achieved regardless of TEP timing (primary versus secondary). Overall favorable speech outcomes occurred in the setting of a patient population of 65% salvage laryngectomy after previous radiation therapy. Complications were common, as 83% of patients had any type of complication affecting the TEP (including both major and minor and those indirectly and directly related to TEP) and 61% had multiple such complications. However, relatively few of these complications required surgical intervention, and only 6% of patients ultimately required TEP removal. There was no difference in complications among patients categorized according to timing of TEP and relation of timing of radiation therapy to TEP placement. Even in patients with free flap reconstruction, there was no difference in complication rates between primary and secondary TEP, although TEP use was higher among free flap patients undergoing secondary TEP (Figure II).

Results here are in concordance with other studies that found no significant difference in complication rates of primary and secondary TEP4,10, 20, 22, 33, 34. Direct complications in the current study (64.6% and 60.9% for primary and secondary TEP respectively) were slightly higher than others reported, which may be explained by the comprehensive inclusion and prospective tracking of complications, long-term follow up of 4.7 years, and high rate of radiation therapy (only 8.3% of this cohort did not require radiotherapy)4, 20. TEP outcomes, as measured by long-term use of TEP (82% for primary and 85% for secondary TEP) were slightly higher than other reported rates of 75–78% for primary TEP and 67–71% for secondary TEP that have been published since the recent trend of increased frequency of salvage laryngectomy20, 35. As reported in several other studies, there was no significant difference in success rate (as measured by TEP use or fluency) between patients who received radiation and those who did not4,7,13,14,36. Although it was not statistically significant, all patients who did not receive radiation were fluent and using their TEP, similar to favorable patient outcomes reported by Silverman and Cantu8,9 in this patient population.

Pharyngocutaneous fistula, pharyngoesophageal spasm, pharyngeal stricture, lymphedema and stomal stenosis are complications that may not be a direct consequence of TEP but can ultimately affect speech outcomes. Our rates of these complications and management techniques are summarized in table II. Of the 31 patients (21%) in this study who had pharyngoesophageal spasm, over two-thirds (22 patients) were severe enough to warrant botulinum toxin. While this number is slightly higher than reported in the literature, the definition of spasm in this study included patients with even transient or a small degree of spasm that did not require botulinum injection6,7. This series had a high rate of stomal stenosis compared to the 18–29% percent reported in other TEP studies,4, 15 likely because of the varying definitions of stenosis across different studies. The current study included patients with mild, transient stenosis immediately post-operatively and during radiation therapy, accounting for higher reported rates.

Complications directly related to TEP included enlarged TEP, aspiration of the prosthesis, pneumonia secondary to leakage, spontaneous TEP closure, partial tract closure/stenosis, granulation tissue buildup, superior tract migration, and frequent leakage through the TEP. The goals of management for enlarged TEP or premature valve failure causing frequent leakage through the valve are to control aspiration and maintain communication. First, a thorough swallow evaluation is completed and any strictures are treated, as this an often overlooked underlying cause of prosthetic leakage. The enlarged puncture can also be managed with clinic procedures such as injection, placement of purse string sutures, or prosthetic customization11,23,24. While rare, refractory enlargement can require major surgery with free flap reconstruction37. Conversely, partial tract closure is often a consequence of incorrect sizing or tract swelling causing the prosthesis to pull or embed mid-tract, ultimately resulting in stenosis of the posterior tract. It is managed by prosthetic management to reestablish fit of the prosthesis.

Several studies have shown the feasibility of TEP in previously radiated patients undergoing free flap reconstruction38,39. Thirty-one (21%) patients in the current study had free-flap reconstruction. The majority of these patients had secondary TEP due to concern for complications and expectation of potentially delayed wound healing in previously irradiated tissue (Figure II). Another reason for delayed TEP puncture in these patients was concern for speech quality in this cohort. After some types of free-flap reconstruction (particularly tubed free flaps and jejunal interpositions), the quality of TEP speech has previously been reported to be more variable and suboptimal relative to pharyngeal closure without free flap reconstruction40. Secondary TEP after laryngectomy gives patients the opportunity to trial esophageal insufflation with the speech language pathologist and determine whether TEP speech yields acceptable voicing for the patient prior to puncture. This is likely why the specific subgroup of free flap patients had improved TEP use with a secondary TEP procedure, despite having significantly higher rates of previous radiation and more extensive surgical resection and reconstruction (as compared to the primary TEP free-flap cohort).

An important context of this retrospective study is the selection bias in choosing patients for TEP candidacy, and for selection of primary versus secondary TEP. Based on our strict selection criteria, only 60% of patients undergo TEP after total laryngectomy21,41. Additionally, over the last several decades, the practice at this institution has moved toward secondary TEP in patients who are at perceived higher risk for wound complications, including those with significant radiation sequelae, major pharyngeal resection and reconstruction with free flap, and significant medical comorbidities. Therefore, non-significant differences in complications between primary and secondary TEP patients should be understood in the context of patient selection. This selection bias is highlighted by a higher rate of secondary TEP’s in patients with free flap reconstruction, with two-thirds of the free flap cohort undergoing secondary TEP.

A potential limitation of this study is that although a standard technique to determine fluency22 was used, the interrater reliability of fluency outcome could not be assessed as it was ascertained by a single trained provider at the point of service. However, ordinal grading of perceptual speech ratings has been shown to be highly reliable among TE speakers (94% and 93% inter- and intra-rater agreement) in published prospective work42.

There has been a national trend towards organ preservation, with the rate of total laryngectomy cases decreasing and concentrating in high-volume centers 43,44,45. The coordinated efforts of an experienced team of providers in these high-volume centers is essential in the post-operative care of laryngectomy patients in order to maximize speech outcomes. This large cohort of TEP patients with long-term follow up had favorable TEP use and speech outcomes, reflecting the care of an experienced team optimizing patient selection and dynamic post-procedure management of TEP patients. Complication rates associated with TEP were high overall, and although the majority were minor, their management required a high level speech language pathology expertise and often frequent clinic visits.

CONCLUSION

Careful selection of patients’ candidacy for TEP provided similar TE speech outcomes and complication rates regardless of timing of TEP or radiation. For more complex patients who require extended surgical resection and reconstruction, secondary TEP may be a better option to achieve successful voice restoration due to opportunity for enhanced pre-TEP testing, education, and selection.

Footnotes

Previously presented: Updated from data presented as an abstract at the 2009 American Head and Neck Society Meeting in Phoenix, Arizona

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Hutcheson receives grant support from the MD Anderson Institutional Research Grant Program and the National Cancer Institute (R03 CA188162).

References

- 1.Robertson SM, Yeo JC, Dunnet C, Young D, Mackenzie K. Voice, swallowing, and quality of life after total laryngectomy: results of the west of Scotland laryngectomy audit. Head Neck. 2012;34:59–65. doi: 10.1002/hed.21692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stafford FW. Current indications and complications of tracheoesophageal puncture for voice restoration after laryngectomy. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11:89–95. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer MI, Blom ED. An endoscopic technique for restoration of voice after laryngectomy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1980;89:529–33. doi: 10.1177/000348948008900608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng E, Ho M, Ganz C, et al. Outcomes of primary and secondary tracheoesophageal puncture: a 16-year retrospective analysis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2006;85:264–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Op de Coul BM, Hilgers F, Balm AJ, et al. A decade of post laryngectomy vocal rehabilitation in 318 patients. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:1320–7. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.11.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emerick KS, Tomycz L, Bradford CR, Lyden TH, Chepeha DB, Wolf GT, Teknos TN. Primary versus secondary tracheoesophageal puncture in salvage total laryngectomy following chemoradiation. Otolaryngology--Head Neck Surg. 2009;140:386–390. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chone CT, Gripp FM, Spina AL, Crespo AN. Primary versus secondary tracheoesophageal puncture for speech rehabilitation in total laryngectomy: long-term results with indwelling voice prosthesis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantu E, Ryan WJ, Tansey S, et al. Tracheosesophageal speech: Predictors of success and social validity ratings. Am J otolaryngol. 1998;19:12–17. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(98)90059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman AH, Black MJ. Efficacy of primary tracheoesophageal puncture in laryngectomy rehabilitation. J Otolaryngol. 1994;23:370–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manglia AJ, Lundy DS, Casiano RC, Swim SC. Speech restoration and complications of primary versus secondary tracheoesophageal puncture following total laryngectomy. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:489–91. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutcheson KA, Lewin JS, Sturgis EM, Risser J. Multivariable analysis of risk factors for enlargement of the tracheoesophageal puncture after total laryngectomy. Head neck. 2012;34:557–567. doi: 10.1002/hed.21777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutcheson KA, Lewin JS, Sturgis EM, Kapadi A, Risser J. Enlarged tracheoesophageal puncture after total laryngectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head & neck. 2011;33:20–30. doi: 10.1002/hed.21399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kao WW, Mohr RM, Kimmel CA, et al. The outcome and techniques of primary and secondary tracheoesophageal puncture. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120:301–7. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1994.01880270047009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bascolo-Rizzo P, Zanetti F, Carpene S, Da Mosto MC. Long-term results with tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis: primary versus secondary TEP. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265:73–77. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trudeau MD, Schuller DE, Hall DA. Timing of tracheoesophageal puncture for voice restoration: primary versus secondary. Head Neck. 1988;82:130–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trudeau MD, Schuller DE, Hall DA. The effects of radiation on tracheoesophageal puncture. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;115:1116–7. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1989.01860330106028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrews MD, Mickel RA, Hanson DG, et al. Major complications following tracheoesophageal puncture for voice rehabilitation. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:562–7. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198705000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward PH, Andrews JC, Mickel RA, et al. Complications of medical and surgical approaches to voice restoration after total laryngectomy. Head Neck Surg. 1988;10:S124–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehle ME, Lavertu P, Meeker SS, et al. Complication of secondary tracheoesophageal puncture: the Cleveland Clinic Foundation experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;106:189–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moon S, Raffa F, Ojo R, Landera MA, Weed DT, Sargi Z, Lundy D. Changing trends of speech outcomes after total laryngectomy in the 21st century: a single-center study. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:2508–12. doi: 10.1002/lary.24717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewin JS, Hutcheson KA. General Principles of rehabilitation of speech, voice, and swallowing function after treatment of head and neck cancer. In: Harrison LB, Sessions RB, Hong WK, editors. Head and neck cancer: a multidisciplinary approach. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. pp. 168–180. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewin JS, Baugh RF, Baker SR. An objective method for prediction of tracheoesophageal speech production. J Speech Hear Disord. 1987;52:212–217. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5203.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewin JS, Hutcheson KA, Barringer DA, Croegaert LE, Lisec A, Chambers MS. Customization of the voice prosthesis to prevent leakage from the enlarged tracheoesophageal puncture: results of a prospective trial. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1767–1772. doi: 10.1002/lary.23368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shuaib SW, Hutcheson KA, Knott JK, Lewin JS, Kupferman ME. Minimally invasive approach for the management of the leaking tracheoesophageal puncture. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:590–594. doi: 10.1002/lary.22401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenz KJ, Grieser L, Ehrhart T, Maier H. Role of reflux in tracheoesophageal fistula problems after laryngectomy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2010;119:719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galli J, De Corso E, Volante M, Almadori G, Paludetti G. Postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistula: incidence, predisposing factors, and therapy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dowthwaite SA, Penhearow J, Szeto C, Nichols A, Franklin J, Fung K, Yoo J. Postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistula: determining the risk of preoperative tracheostomy and primary tracheoesophageal puncture. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;41:169–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewin JS, Bishop-Leone JK, Forman AD, Diaz EM. Further experience with Botox injection for tracheoesophageal speech failure. Head neck. 2001;23:456–460. doi: 10.1002/hed.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terrell JE, Lewin JS, Esclamado R. Botulinum toxin injection for postlaryngectomy tracheoesophageal speech failure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113:788–791. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sweeny L, Golden JB, White HN, Magnuson JS, Carroll WR, Rosenthal EL. Incidence and Outcomes of Stricture Formation Postlaryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:395–402. doi: 10.1177/0194599811430911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith BG, Hutcheson KA, Little LG, Skoracki RJ, Rosenthal DI, Lai SY, Lewin JS. Lymphedema outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:284–291. doi: 10.1177/0194599814558402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewin JS. Nonsurgical management of the stoma to maximize tracheoesophageal speech. Otolaryngologic clinics N Amer. 2004;37:585–596. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundy DS, Landera MA, Bremekamp J, Weed D. Longitudinal tracheoesophageal puncture size stability. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147:885–888. doi: 10.1177/0194599812449293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlen RG, Maisel RH. Does primary tracheoesophageal puncture reduce complications after laryngectomy and improve patient communication? Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22:324–8. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2001.26491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dayangku Norsuhazenah PS, Baki MM, Mohamad Yunus MR, Sabir Husin Athar PP, Abdullah S. Complications following tracheoesophageal puncture: a tertiary hospital experience. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39:565–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guttman D, Mizrachi A, Hadar T, Bachar G, Hamzani Y, Marx S, Shvero J. Post-laryngectomy voice rehabilitation: comparison of primary and secondary tracheoesophageal puncture. IMAJ. 2013;15:497–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hutcheson KA, Lewin JS, Sturgis EM, Risser J. Outcomes and adverse events of enlarged tracheoesophageal puncture after laryngectomy. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1455–1461. doi: 10.1002/lary.21807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scharpf J, Esclamado RM. Reconstruction with radial forearm flaps after ablative surgery for hypopharyngeal cancer. Head neck. 2003;25:261–266. doi: 10.1002/hed.10197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinclair CF, Rosenthal EL, McColloch NL, Magnuson JS, Desmond RA, Peters GE, Carroll WR. Primary versus delayed tracheoesophageal puncture for laryngopharyngectomy with free flap reconstruction. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1436–1440. doi: 10.1002/lary.21836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deschler DG, Doherty ET, Anthony JP, Reed CG, Singer MI. Tracheoesophageal voice following tubed free radial forearm flap reconstruction of the neopharynx. Annals Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103:929–936. doi: 10.1177/000348949410301202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferrel JK, Hutcheson KA, Anzalone CL, Lewin JS, Hessel AC. Factors Contributing to the Decision to Perform Tracheoesophageal Puncture for Voice Restoration in the Total Laryngectomy Population. Poster presentation at the 5th World Congress of the International Federation of Head and Neck Oncologic Societies (IFHNOS) and the American Head and Neck Society (AHNS) Annual Meeting; New York, NY. 7/26/2014. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dworkin JP, Meleca RJ, Zacharek MA, Stachler RJ, Pasha R, Abkarian GG, Culatta RA, Jacobs JR. Voice and deglutition functions after the supracricoid and total laryngectomy procedures for advanced stage laryngeal carcinoma. Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery. 2003 Oct 1;129(4):311–20. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59980301314-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orosco RK, Weisman RA, Chang DC, Brumund KT. Total Laryngectomy National and Regional Case Volume Trends 1998–2008. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148:243–248. doi: 10.1177/0194599812466645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maddox PT, Davies L. Trends in Total Laryngectomy in the Era of Organ Preservation A Population-Based Study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147:85–90. doi: 10.1177/0194599812438170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sandulache VC, Vandelaar LJ, Skinner HD, et al. Salvage Total Laryngectomy Following External Beam Radiation Therapy: A 20 Year Experience. doi: 10.1002/hed.24355. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]