Abstract

Among older adults, distressing symptoms are associated with decreased function, acute care use and mortality. The number of older jail inmates is increasing rapidly, prompting calls to develop systems of care to meet their healthcare needs. Yet little is known about multidimensional symptom burden in this population. This cross-sectional study describes the prevalence and factors associated with distressing symptoms and the overlap between different forms of symptom distress in 125 older jail inmates in an urban county jail. Physical distress was assessed using the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale. Several other forms of symptom distress were also examined, including: psychological (GAD-2 and PHQ-2), existential (Patient Dignity Inventory), and social (Three Item Loneliness Scale). Participant sociodemographics, multimorbidity, serious mental illness (SMI), functional impairment and behavioral health risk factors were collected through self-report and chart review. Chi-squared tests were used to identify factors associated with physical distress. Overlap between forms of distress was evaluated using set theory analysis. Overall, many participants (74%) reported distressing symptoms including having one or more physical (44%), psychological (37%), existential (54%), or social (45%) symptom. Physical distress was associated with poor health (multimorbidity, functional impairment, SMI) and low income. Of the 93 participants with any symptom, 49% reported 3 or more forms of distress. These findings suggest that an optimal model of care for this population would include a geriatrics-palliative care approach that integrates the management of all forms of symptom distress into a comprehensive treatment paradigm stretching from jail to the community.

Keywords: Distressing symptoms, older inmates, palliative care, jail

INTRODUCTION

Over 550,000 adults aged 55 or older are arrested and detained in jail each year, prompting calls to develop appropriate systems of healthcare for this growing population.1,2 Many of these older jail inmates experience multimorbidity including early-onset functional and cognitive impairment.3 Yet little is known about how best to meet their healthcare needs.4

The fields of geriatrics and palliative care have made critical strides in establishing the importance of assessing and managing symptoms for older adults with chronic illness and/or multimorbidity.5,6 This is important because symptoms lead to adverse health outcomes. For example, physical symptoms are independently associated with worsening quality of life, future functional impairment, patient dissatisfaction, and increased healthcare costs via greater primary care and urgent care visits.7,8 Psychological and social symptoms also contribute to worse physical distress and poorer health outcomes.9,10 And a growing body of evidence suggests that existential suffering, which adversely affects quality of life and overall well-being, may also contribute to worse physical health among the seriously ill, though the literature exploring the link between existential distress and physical health outcomes is still in its early stages.11,12 Despite a rapidly growing number of older jail inmates, little is known about the type or degree of distressing symptoms experienced by this population, or the health and social factors associated with symptom burden.

Addressing symptom burden is an important factor in designing cost-effective, patient-centered care for older adults.13 This is likely particularly true for older jail inmates, a population that has a high burden of multimorbidity and frequently experiences concomitant social challenges such as homelessness and substance use disorders.3 Studies show that jail-based health interventions and continuity of care from jail detainment through the post-release period can reduce recidivism and improve health for persons with chronic diseases such as HIV and serious mental illness.14,15 Other studies show that pain is often undertreated among older jail inmates2 and is associated with recent acute care use,3 suggesting that identifying and addressing symptoms in this population could improve their health and social outcomes.

Despite the strong association between symptom management and better health outcomes in community-dwelling older adults, little is known about the symptom burden of their jail-based counterparts. To address this knowledge gap, this study describes the extent of multidimensional symptom burden in older jail inmates, including physical, psychological, social and existential distress; identifies patient factors commonly associated with these distressing symptoms; and determines the degree of overlap among symptoms. This information is an important starting point for developing a model of care to meet the complex healthcare needs of older jail inmates.

METHODS

Study design and sample

This cross-sectional study includes 125 participants aged 55 or older who were incarcerated in an urban county jail between March 1 and August 15, 2014. To be consistent with other criminal justice studies, age 55 was used to describe “older” inmates due to a high burden of age-related chronic illnesses and disability that are experienced among this population at relatively young ages. This “accelerated aging” is likely the consequence of a lifetime accumulation of stressors such as poor access to healthcare and homelessness.4 Study eligibility included ability to speak English or Spanish (the two most commonly spoken languages in the jail), not posing a safety risk to interviewers (according to the deputy on duty), and being incarcerated for at least 48 hours. The 48-hour cutoff was used because inmates are often in transit or have court appearances within 48 hours of arrest and are therefore less available to participate in a research study.

Research participation consent was obtained using a teach-to-goal method, shown to be an effective method for achieving informed consent for epidemiologic studies among older adults with low literacy.16 Native-speaking interviewers read questionnaires to participants in private interview rooms and research staff abstracted medical records. Consistent with relevant ethical considerations,17 all participants received $20 in their jail accounts as compensation for their time. This study was approved by the Human Research Protection Program at the University of California, San Francisco.

Measures

Physical Distress

Physical distress was assessed using questions from the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS).18 This scale has been used to assess physical distress in other medically vulnerable populations, including older adults.19 Distressing physical symptoms were defined as those that were reported to: 1) occur “frequently” or “almost constantly,” 2) be “moderately severe”, “severe”, or “very severe,” and 3) be “somewhat”, “quite a bit” or “very much” bothersome. Participant responses were categorized as having no physically distressing symptoms versus having one or more physically distressing symptoms.

Other Forms of Distress

Additional forms of distress that are associated with adverse health outcomes in older adults (e.g. acute care use, morbidity, mortality) were assessed, including symptoms of psychological distress (depression10 and anxiety20), social distress (loneliness9), and existential distress.12 Symptoms of psychological distress were defined as having one or more depressive symptom (a positive score on the Patient Health Questionaire-2) and/or one or more anxiety symptom (a positive score on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2).21 Social distress was defined as a positive screen on the validated Three Item Loneliness Scale.9 Existential distress was defined as reporting that any one of 10 measures of existential distress in the Patient Dignity Inventory (PDI) was a “major” or “overwhelming” problem. The Patient Dignity Inventory is a relatively novel scale that has been validated for use among patients with serious illness.11 It was used in this study because it is a valid and reliable measure of existential distress (a sub-domain within the PDI) that can be used to guide dignity-affirming clinical care and because no other measure of existential distress, to our knowledge, has been validated outside the context of serious illness. Two additional measures were added to the assessment of existential distress based on prior correctional health research22,23 and the authors’ clinical experiences with this population: “Fear of dying in jail or prison instead of as a free person” and “Feeling like you have missed out on things or relationships in life because of alcohol or substance abuse.”

Sociodemographics, health conditions, and transitional care challenges

Self-reported participant sociodemographics included age, race/ethnicity, gender, income, and education level. Income was categorized as above or below $15,000 since this is the approximate federal cut-off for income-related Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act (133% below the federal poverty line).24 Homelessness was defined as spending at least one night outside or in a homeless shelter within thirty days of arrest.25 Self-rated health and chronic conditions were assessed using a combination of chart review and self-report via validated questions from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS).26

Self-report of medical conditions is well validated in older populations, including in homeless populations.27 Functional impairment was defined as having difficulty with one or more Activity of Daily Living (eating, bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring). Serious mental illness was defined using the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ definition of any major depressive, mania, or psychotic disorder28 and was determined using a combination of self-reported diagnosis and medical chart abstraction. Recent drug use was defined as a positive screen for “moderate”, “substantial,” or “severe” problem drug use using the Drug Abuse Screening Test-10 (DAST-10), an instrument validated for use with incarcerated persons.29 Problem alcohol use was defined as a positive screen for “hazardous drinking” or having an “active alcohol use disorder” using the three-item Modified Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C).30

To assess the relationship between distressing symptoms and healthcare-related challenges encountered during reentry from jail to the community, several anticipated experiences were assessed via closed-ended questions. These included feeling a lack of control over one’s health, defined using a validated measure from the HRS;26 and reporting concern about staying safe following release from jail (rated 8 or greater on a scale of 0 to 10 where 10 is extremely concerned). Participants also were asked whether they had a community-based primary care provider.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe participant characteristics and distressing symptoms. Bivariate analysis with chi-square tests were used to examine the relationship between distressing physical symptoms and sociodemographic, health, and other symptoms. To illustrate the relationship between physical distress and other forms of distress (psychological, social, and existential), set theory analysis was used to construct a Venn diagram. Analyses were performed using Stata, version 12 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

During the study period, 158 inmates age 55 or older were incarcerated for more than 48 hours and met study eligibility requirements. Of these, 15 (10%) declined to be contacted by staff about the study and 13 (8%) agreed to be contacted but were released before they could meet with research staff. Of the remaining 130 adults recruited to the study (82% of those eligible), 5 (3.8%) were excluded: 4 (3%) could not provide informed consent via the teach-to-goal period and 1 (0.8%) violated study protocol during the baseline interview and was withdrawn from the study. This resulted in a final sample of 125 participants. Overall, participants ranged from 55 to 87 years old with an average age of 60. Most were black (67%), male (94%), and had an income below 133% of the federal poverty line (86%). Participants were in jail for an average of 6.9 days (median 6 days) at the time of study participation.

Distressing symptoms

Overall, 55 (44%) participants reported having at least one distressing physical symptom. The most common distressing physical symptoms were pain (28%) and difficulty sleeping (15%), Table 1. Many participants reported experiencing at least one indicator of existential distress (54%); nearly half reported social distress (45%); and over a third reported symptoms of psychological distress (37%). The most common symptoms of existential distress were missing out on things in life due to substance use (30%), having “unfinished business” (23%), and fear of dying during incarceration instead of as a free person (27%). Among participants experiencing distressing psychological symptoms, 32 (26%) scored positive on the PHQ-2 for depressive symptoms and 38 (30%) scored positive on the GAD-2 for anxiety symptoms.

Table 1.

Study sample characteristics and distressing symptom burden, N=125

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Sociodemographics | |

| Age (y), Mean (± SD), Range | 60.1 ± 5.0, 55–87 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black | 84 (67) |

| White/Non-Latino | 24 (19) |

| Latino | 8 (6) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4 (3) |

| Mixed Race/Other | 5 (4) |

| Female | 8 (6) |

| Annual Income <$15,000 | 108 (86) |

| Education | |

| Less than a high school degree | 33 (26) |

| Received GED in the community, jail or prison | 17 (14) |

| Completed high school degree in community | 35 (28) |

| Completed some college but no degree | 33 (26) |

| Achieved a college degree or higher | 7 (6) |

|

| |

| Chronic Illness | |

| Hypertension | 75 (60) |

| Diabetes | 20 (16) |

| Cancer (not including skin) | 3 (2) |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 25 (20) |

| Heart attack, coronary disease, or angina | 15 (12) |

| Congestive heart failure | 7 (6) |

| Stroke | 8 (6) |

| HIV/AIDS | 9 (7) |

| Dialysis (Chronic Renal Failure) | 1 (1) |

| Hepatitis C (HCV) | 59 (48) |

| Arthritis | 55 (44) |

| Pulmonary Hypertension | 1 (1) |

| Cirrhosis | 1 (1) |

| 1 or more chronic illness | 107 (86) |

| 2 or more chronic illnesses | 76 (61) |

|

| |

| Serious Mental Illness (SMI) | 53 (42) |

|

| |

| (+) Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) a | 82 (66) |

| (+) Modified Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) b | 47 (38) |

|

| |

| Functional Ability | |

| Needing help with one or more ADL | 68 (54) |

|

| |

| Self-Rated Health | |

| Poor or Fair | 61 (49) |

| Good, very good or excellent | 64 (51) |

|

| |

| Transitional Care Challenges | |

| Homelessnessc | 73 (61) |

| Lack of control over healthd | 24 (20) |

| High concern about staying safe following release from jaile | 53 (42) |

| No primary care provider | 48 (38) |

|

| |

| Distressing Physical Symptomsf | |

| Distressing, frequent… | |

| …Pain | 35 (28) |

| …Lack of energy | 9 (7) |

| …Cough | 8 (6) |

| …Nausea or vomiting | 3 (2) |

| …Feeling drowsy | 3 (2) |

| …Difficulty sleeping | 19 (15) |

| …Shortness of breath | 10 (8) |

| …Diarrhea | 6 (5) |

| …Sweats | 5 (4) |

| …Itching | 12 (10) |

| …Lack of appetite | 5 (4) |

| …Dizziness | 6 (5) |

| One or more distressing physical symptom | 55 (44) |

|

| |

| Distressing Psychological Symptomsg | |

| Depression | 32 (26) |

| Anxiety | 38 (30) |

| One or more psychological symptom | 46 (37) |

|

| |

| Existential distressh | |

| Feeling like you are no longer who you used to be | 15 (12) |

| Not feeling worthwhile or valued | 12 (10) |

| Not being able to carry out important roles | 18 (14) |

| Feeling that life no longer has meaning or purpose | 9 (7) |

| Feeling that you have not made a meaningful or lasting contribution in your life | 16 (13) |

| Feeling of having ‘unfinished business’ | 28 (23) |

| Concern that spiritual life is not meaningful | 8 (6) |

| Feeling like a burden to others | 10 (8) |

| Feeling guilty | 22 (18) |

| Feeling that you have missed out on things in life due to substance use | 38 (30) |

| Fear of dying in jail or prison rather than as a free person | 34 (27) |

| One or more symptom of existential distress | 68 (54) |

|

| |

| Social distressi | |

| One or more symptom of Loneliness | 56 (45) |

“moderate”, “substantial” and “severe” problem drug use in the Drug Abuse Screening Test

hazardous drinking or active alcohol use disorder in the AUDIT-C

spending at least one night outside or in a homeless shelter within thirty days of arrest

a response of “3” or lower to the HRS question: “Using a 0–10 scale, where 0 means ‘no control at all’ and 10 means ‘very much control’, how much control do you have over your health these days?”

a response of “8” or higher to the statement, “On a scale of 0 to ten, where 0 is not concerned at all and 10 is extremely concerned, tell me how concerned you are about staying safe.”

symptom reported to: 1) occur “frequently” or “almost constantly,” 2) be “moderately severe”, “severe”, or “very severe,” and 3) be “somewhat”, “quite a bit” or “very much” bothersome using the MSAS

reporting one or more depressive symptom on the Patient Health Questionaire-2 and/or one or more anxiety symptom on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2)

reporting that any one of 10 measures of existential distress in the Patient Dignity Inventory (PDI) was a “major” or “overwhelming” problem.

a positive screen on the validated Three Item Loneliness Scale

Health conditions and transitional care challenges

The majority of participants (61%) had two or more chronic conditions such as Hepatitis C (48%), diabetes (16%), heart disease (12%) and/or congestive heart failure (6%), Table 1. More than half had one or more ADL impairment (54%). Many participants (66%) registered a positive screen for moderate, substantial, or severe problem drug use and 47 (38%) registered a positive screen for hazardous drinking or having an active alcohol use disorder.

Many participants anticipated transitional care challenges after their release from jail, although more than half (62%) reported having a primary care provider (PCP) outside of jail. Of these, 52% reported a PCP in a community clinic, 31% saw a hospital-based or private PCP, and 17% received primary care at the VA. One in five participants (20%) reported feeling that they had very little control over their health. Social challenges were also common, including homelessness (61%) and being concerned about personal safety following release (42%).

Characteristics associated with distressing physical symptoms

The presence of any distressing physical symptom was associated with having an annual income less than $15,000 (96% vs. 79%, p=0.004), poor self-rated health (33% vs 9%, p<0.001), 2 or more chronic medical conditions (80% vs 46%, p<0.001), serious mental illness (55% vs 33%, p= 0.015), and one or more ADL impairment (80% vs 34%, p<0.001), Table 2. Having a physically distressing symptom was also associated with reporting one or more symptom of each of the other forms of distress assessed: social distress (65% vs 29%, p<0.001), existential distress (78% vs 36%, p<0.001), and psychological distress (56% vs 21%, p<0.001). Among transitional care and social challenges, only feeling a lack of control over one’s health had a significant association with distressing physical symptom burden (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics associated with reporting a physically distressing symptom, N=125

| Characteristic | No Distressing Physical Symptoms (n=70, 56%), N (%) | One or More Distressing Physical Symptoms (n=55, 44%), N (%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age (y), Mean (± SD), Range | 59.7 ± 5.1, 55–87 | 60.7 ± 4.9, 55–77 | 0.289 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black | 51 (73) | 33 (60) | 0.129 |

| White/Non-Latino | 13 (19) | 11 (20) | |

| Latino | 2 (3) | 6 (11) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3 (4) | 1 (2) | |

| Mixed Race/Other | 1 (1) | 4 (7) | |

| Female | 4 (6) | 4 (7) | 0.730 |

| Annual Income <$15,000 | 55 (79) | 53 (96) | 0.004 |

| Education | |||

| Less than a high school degree | 18 (26) | 15 (27) | 0.927 |

| Received GED in the community, jail or prison (nothing further) | 8 (11) | 9 (16) | |

| Completed high school degree in community | 20 (29) | 15 (27) | |

| Some college but no degree | 20 (29) | 13 (24) | |

| College degree or higher | 4 (6) | 3 (5) | |

|

| |||

| Self-Rated Health | |||

| Poor or Fair | 25 (36) | 36 (65) | 0.001 |

| Good, very good or excellent | 45 (64) | 19 (35) | |

|

| |||

| Chronic medical conditions | |||

| Hypertension | 34 (49) | 41 (75) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes | 7 (10) | 13 (24) | 0.042 |

| Cancer (not including skin) | 1 (1) | 2 (4) | 0.582 |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 10 (14) | 15 (27) | 0.072 |

| Heart attack, coronary disease, or angina | 3 (4) | 12 (22) | 0.005 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2 (3) | 5 (9) | 0.139 |

| Stroke | 2 (3) | 6 (11) | 0.077 |

| HIV/AIDS | 5 (7) | 4 (7) | 0.999 |

| Dialysis (Chronic Renal Failure) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | * |

| HCV | 25 (36) | 34 (64) | 0.002 |

| Arthritis | 21 (30) | 34 (62) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary Hypertension | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | * |

| Cirrhosis | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | * |

| 1 or more chronic medical conditions | 54 (77) | 53 (96) | 0.002 |

| 2 or more chronic medical conditions | 32 (46) | 44 (80) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Serious Mental Illness (SMI) | 23 (33) | 30 (55) | 0.015 |

|

| |||

| (+) Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) | 43 (61) | 39 (71) | 0.268 |

| (+) Modified Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) | 27 (39) | 20 (36) | 0.800 |

|

| |||

| Functional Impairment | |||

| One or more ADL impairment | 24 (34) | 44 (80) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Transitional Care Challenges | |||

| Homelessness | 36 (54) | 37 (71) | 0.053 |

| Lack of control over health | 6 (9) | 18 (33) | <0.001 |

| High concerned about staying safe following release from jail | 25 (36) | 28 (51) | 0.088 |

| No primary care provider | 28 (40) | 20 (36) | 0.678 |

|

| |||

| One or more symptom of psychological distress | 15 (21) | 31 (56) | <0.001 |

| One or more symptom of existential distress | 25 (36) | 43 (78) | <0.001 |

| One or more indicator of social distress | 46 (66) | 48 (87) | 0.005 |

Relationship between different forms of distress

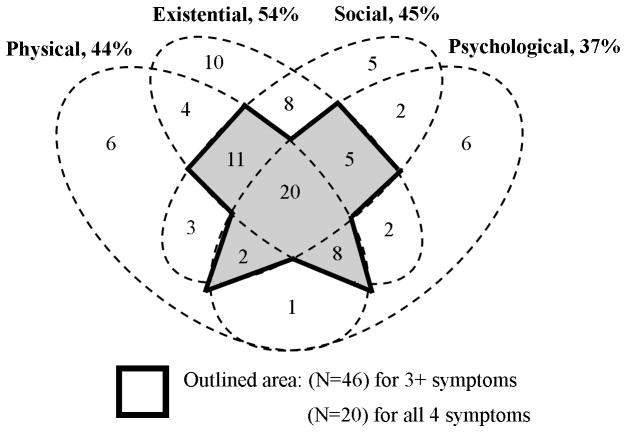

The Venn diagram (Figure) shows the interconnectedness of the different forms of distress examined in this study. Of 93 participants with any distressing symptom, 20 (22%) reported having a distressing symptom in all four categories of distress and 26 (27%) reported a distressing symptom in any 3 of the 4 categories. Of the 55 participants who reported one or more distressing physical symptom, nearly all (49, 89%) reported one or more other form of symptomatic distress (psychological, social, and/or existential).

Figure. Distressing symptoms are common and interconnected, N=125.

This figure shows that of 125 participants, 93 (74%) had at least one distressing symptom. These included physical (44% with one or more), existential (54%), social (45%) and psychological (37%) symptoms. The outlined area in the center of the Venn Diagram shows that of the 93 participants with any distressing symptom, 46 (49%) reported experiencing 3 or more forms of distress and 20 (22%) experienced all 4 forms of distress.

DISCUSSION

This study found that symptom distress among older jail inmates is common and multidimensional. Many participants (74%) described having at least 1 symptom of physical distress (44%), psychological distress (56%), social distress (45%), and/or existential distress (54%), oftentimes concurrently. Among participants with any form of symptomatic distress, nearly half (49%) experienced 3 or more forms of distress. While traditional approaches to symptomatic distress often focus primarily on the management of physical symptoms, this study’s findings add to a growing body of literature suggesting that different forms of distress are often interconnected, co-occurring, and relevant to the overall health outcomes of older adults.5,7,8, 9,20

The older jail inmates in this study experienced a particularly strong overlap between physical distress and other forms of distress. Of the 55 participants who reported physical distress, most (89%) reported experiencing concurrent psychological, social, and/or existential distress. These findings are consistent with other studies in other populations showing an inadequate treatment of non-physical symptoms in the setting of physical distress and chronic illness10,12,13 and suggest that a multidimensional approach to symptom assessment and management may be of particular benefit for this population.5,8,19

Such recommendations for holistic symptom management have been translated into clinical practice guidelines by the National Consensus Project that include assessment and treatment of patients’ spiritual, religious, and existential needs.31 While clinicians tasked with caring for older jail inmates must often focus their efforts on patients’ medical conditions such as Hepatitis C, multi-morbidity, and functional impairment, our findings suggest that existential suffering often co-exists with these and other health challenges. As a result, clinicians may benefit from an understanding of dignity-conserving care and related palliative care treatment models. This multidimensional approach to care would be consistent with the growing recognition that palliative care can serve as a strategy to address advanced chronic illness.5 However, additional research is needed to better understand the extent of multidimensional suffering in many marginalized or medically vulnerable populations and the appropriateness of palliative care paradigms in what have been previously thought of as setting that are outside of the purview of palliative care.

This study also found that a high symptomatology burden among older jail inmates often occurred in the context of disproportionately high rates of chronic medical conditions. For example, older jail inmates with an average age of 60 years in this study reported poor or fair health (49%), chronic lung disease (20%), and ADL impairment (54%) at rates similar to those reported by community-based lower income older adults with an average age of 72 years (51% poor or fair health, 23% lung disease, and 36% difficulty walking).13 As a result, integrated models of care that borrow strategies from both geriatrics and palliative care may be a critical first place to start meeting the complex healthcare needs of this population. Such models (in which elements are drawn from geriatrics and palliative care) have transformed health among other vulnerable populations. For example, the GRACE model integrates geriatrics and palliative care to improve health and lower costs for low-income older adults with multiple chronic conditions and high symptom burden.6

Prior work shows that poor health worsens the success of transitions from incarceration to the community, for example by increasing the challenge to securing housing, employment, and benefits.32 This study’s findings raise the concern that symptoms left unaddressed in jail could further limit older adults’ functional ability upon their return to the community and negatively impact their health-related post-release outcomes. Indeed, many participants reported being homeless (61%) and living below the poverty line (87%). While 62% reported having a primary care provider, this high rate likely reflects San Francisco’s “Healthy SF” program, which mandates that all San Franciscans have health insurance. An integrated jail-to-community multi-disciplinary and intensive transitional care model that includes management of both chronic medical conditions, as well as different forms of distressing symptoms, may further help primary care providers meet the complex health and social needs of this population.

There are several limitations to consider while interpreting these results. This study was conducted in one urban county jail system which might limit the generalizability of these findings. However, this study is the first of its kind to describe distressing symptom burden in older jail inmates and is therefore an important step to understanding the extent of unaddressed symptoms in this population. In addition, the measure of existential distress used in this study is typically implemented in the course of clinical care for seriously ill patients. Although measures of existential distress have not been validated outside of palliative care, the high incidence of medical conditions alongside co-occurring physical, social, and psychological distress found in this exploratory study suggests that existential distress is clinically relevant in older jail inmates. This finding also echoes the call of palliative care leaders to extend the use of palliative care assessment and treatment to address advanced, chronic illness.5

This study provides the first description of distressing symptoms experienced by older jail inmates beyond physical pain and calls attention to the complex healthcare needs of this under-studied population. Strong evidence supports symptom management as a cornerstone of care for older adults with chronic disease5 and several medical associations maintain that the multi-dimensional approach of palliative care is appropriate at all stages of serious illness.33,34 In criminal justice healthcare settings, symptom management is often complicated by multiple factors including clinician concerns about misuse, abuse and diversion of pain medications.2 This study’s finding that many older jail inmates experience multiple chronic health conditions and multidimensional distressing symptoms underscores the need to develop symptom management strategies in jail that reach beyond pharmaceutical pain management to treat other forms of distress as well. Evidence shows that high-touch interprofessional care teams, while expensive, can improve complex patients’ clinical outcomes while lowering overall costs of care.8,13 The high medical, social and symptomatic complexity identified in participants in this study suggests that a geriatrics-palliative care model that integrates symptom distress management into a comprehensive treatment paradigm extending from jails into the community may be of particular benefit to many older jail inmates.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

Marielle Bolano was supported by the Medical Student Training in Aging Research Program (2T35AG026736-11). This work was also supported by a pilot award from the National Palliative Care Research Center, and grants from the UCSF Department of Medicine, the National Institute on Aging (3P30AG044281-02S1), the University of California Office of the President Multicampus Research Programs and Initiatives, and Tideswell at UCSF. Dr. Ritchie is supported by Tideswell at UCSF.

Sponsor’s Role:

Marielle Bolano was supported by the Medical Student Training in Aging Research Program (2T35AG026736-11). This work was also supported by a pilot award from the National Palliative Care Research Center, and grants from the UCSF Department of Medicine, the National Institute on Aging (3P30AG044281-02S1), the University of California Office of the President Multicampus Research Programs and Initiatives, and Tideswell at UCSF. Dr. Ritchie is supported by Tideswell at UCSF. These funding sources had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis or preparation of this paper. Dr. Williams is an employee of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The opinions expressed in this manuscript may not represent those of the VA. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the City and County of San Francisco; nor does mention of the San Francisco Department of Public Health imply its endorsement.

Footnotes

Meeting Presentation:

This paper has been accepted for oral presentation at the annual assembly of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM) in March 2016 and in the Presidential Poster Session at the Annual meeting of the American Geriatrics Society in May 2016.

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. Williams has served as an expert witness and as a court consultant in legal cases related to prison conditions of confinement. These relationships have included: the National ACLU; Squire Patton Boggs; The Center for Constitutional Rights; the Disability Rights Legal Center; Holland and Knight LLP; The University of Denver Student Law Office; and The Office of the Independent Medical Monitor, MI. These relationships had no role in the decision to write this manuscript and did not influence the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. No other authors have conflicts of interest to report (see table).

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | MB | CA | CSR | ISC | BW | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

Author contributions:

The corresponding author affirms that all those who contributed significantly to this work are listed here as authors. Study design and concept: MB, CA, BW; Acquisition of subjects and/or data: MB, CA, BW; Analysis and Interpretation of Data: MB, CA, CSR, ISC, BW; Preparation of Manuscript: MB, CA, CSR, BW.

References

- 1.Snyder HN. Arrest in the United States, 1990–2010. Washington DC: Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2012. p. 26. NCJ 239423. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams BA, Ahalt C, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Smith AK, Goldenson J, Ritchie CS. Pain Behind Bars: The Epidemiology of Pain in Older Jail Inmates in a County Jail. J Palliat Med. 2014 Sep 29; doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chodos AH, Ahalt C, Cenzer IS, Myers J, Goldenson J, Williams BA. Older jail inmates and community acute care use. Am J Public Health. 2014 Sep;104(9):1728–1733. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams BA, Goodwin JS, Baillargeon J, Ahalt C, Walter LC. Addressing the aging crisis in U.S. criminal justice health care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012 Jun;60(6):1150–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03962.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meier D. Palliative care as a quality improvement strategy for advanced, chronic illness. J Healthc Qual. 2005 Jan-Feb;27(1):33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2005.tb00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Buttar AB, Clark DO, Frank KI. Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE): a new model of primary care for low-income seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006 Jul;54(7):1136–1141. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeom H-e, Heidrich SM. Effect of Perceived Barriers to Symptom Management on Quality of Life in Older Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nursing. 2009 Jul;32(4):309–316. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819e239e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, McPhee SJ. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Jan 12;164(1):83–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perissinotto CM, Stijacic Cenzer I, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in older persons: a predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Jul 23;172(14):1078–1083. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blazer DG. Depression in Late Life: Review and Commentary. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2003 Mar 01;58(3):M249–M265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chochinov HM, Hassard T, McClement S, et al. The patient dignity inventory: a novel way of measuring dignity-related distress in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008 Dec;36(6):559–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chochinov HM. Dying, dignity, and new horizons in palliative end-of-life care. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2006 Mar-Apr;56(2):84–103. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.84. quiz 104–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric Care Management for Low-Income Seniors. JAMA. 2007 Dec 12;298(22):2623. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Althoff AL, Zelenev A, Meyer JP, et al. Correlates of Retention in HIV Care After Release from Jail: Results from a Multi-site Study. AIDS and behavior. 2012 Nov 18;17(S2):156–170. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0372-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrissey JP, Cuddeback GS, Cuellar AE, Steadman HJ. The Role of Medicaid Enrollment and Outpatient Service Use in Jail Recidivism Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services. 2007 Jun 01;58(6):794–801. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Williams BA, Barnes DE, Lindquist K, Schillinger D. Use of a modified informed consent process among vulnerable patients: a descriptive study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Aug;21(8):867–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson RK, Letourneau EJ, Olver ME, Miner MH. Incentives for offender research participation are both ethical and practical. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2012:39. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A(9):1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritchie C, Dunn LB, Paul SM, et al. Differences in the Symptom Experience of Older Oncology Outpatients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2014 Apr;47(4):697–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Beurs E, Beekman ATF, van Balkom AJLM, Deeg DJH, van Dyck R, van Tilburg W. Consequences of anxiety in older persons: its effect on disability, well-being and use of health services. Psychological Medicine. 1999 May;29(3):583–593. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Lowe B. An Ultra-Brief Screening Scale for Anxiety and Depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009 Nov 01;50(6):613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marlow E. The impact of health care access on the community reintegration of male parolees. 42nd Annual Communicating Nursing Research Conference; Western Institute of Nursing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adler F, Mueller GO, Laufer W. Chapter 18: A Research Focus on Corrections in Criminology and the Criminal Justice System. 6. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Department of Health and Human Services; Apr 9, 2010. [Accessed May 24, 2015]. New Option for Coverage of Individuals under Medicaid. Public Letter: SMDL#10-005, PPACA#1. Online. http://downloads.cms.gov/cmsgov/archived-downloads/SMDL/downloads/SMD10005.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing: Defining “Homeless” (24 CFR Parts 91, 582, and 283 [Docket No. FR-5333-F-02] RIN 2506-AC26)(2010).

- 26.Growing Older in America: The Health & Retirement Study. National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Last accessed June 4, 2013];Participant Lifestyle Questionnaire. 2012 available from: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/modules/meta/2012/core/qnaire/online/HRS2012_SAQ_Final.pdf.

- 27.Brown RT, Kiely DK, Bharel M, Mitchell SL. Geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Jan;27(1):16–22. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1848-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Washington DC: Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. p. 12. NCJ 213600. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7(4):363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998 Sep 14;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The 2009 National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP) Guidelines (400) Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009 Mar;37(3):485–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solomon AL, Osborne JWL, LoBuglio SF, Mellow J, Mukamal DA. Life After Lockup: Improving Reentry from Jail to the Community. The Urban Institute Justice Policy Center; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion: The Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012 Feb 06;30(8):880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lanken PN, Terry PB, DeLisser HM, et al. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Policy Statement: Palliative Care for Patients with Respiratory Diseases and Critical Illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Apr 15;177(8):912–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]