Abstract

Background

Graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) after liver transplantation (LT) is a deadly complication with very limited data on risk factors, diagnosis and management. We report a case series and a comprehensive review of the literature.

Methods

Data was systematically extracted from reports of GVHD after LT, and from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database. Group comparisons were performed.

Results

156 adult patients with GVHD after LT have been reported. Median time to GVHD onset was 28 days. Clinical features were skin rash (92%), pancytopenia (78%) and diarrhea (65%). 6-month mortality with GVHD after LT was 73%. Sepsis was the most common cause of death (60%). Enterobacter bacteremia, invasive aspergillosis and disseminated Candida infections were frequently reported. Recipient age over 50-years is a risk factor for GVHD after LT. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was over-represented, while chronic hepatitis C was under-represented, in reported United States GVHD cases relative to all UNOS database LT cases. Mortality rate with treatment of GVHD after LT was 84% with high-dose steroids alone, 75–100% with regimens using dose increases of calcineurin inhibitors (CNI), and 55% with IL-2 antagonists. Mortality was 25% in small case series using the CD2-blocker alefacept or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) antagonists.

Conclusions

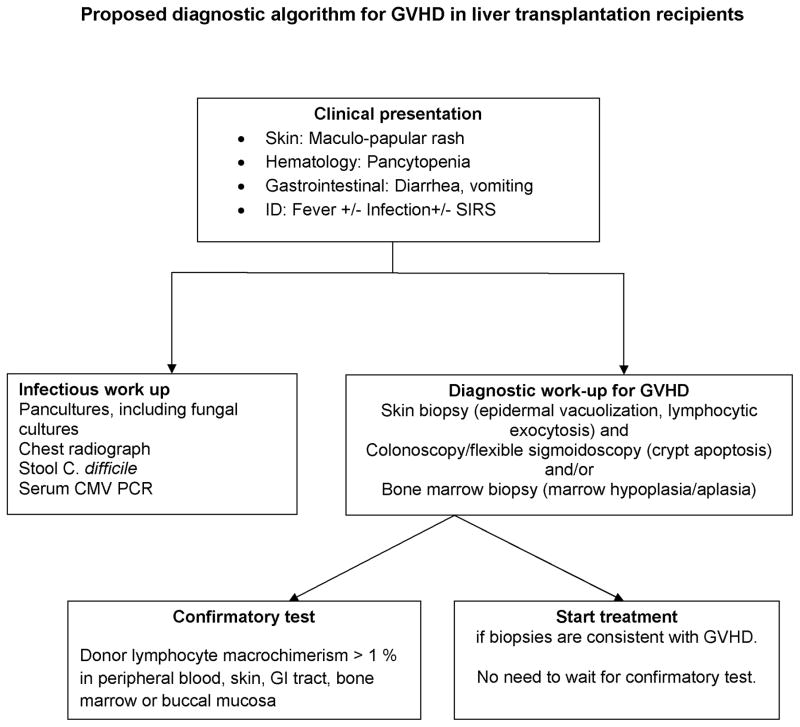

Age over 50-years and HCC appear to be risk factors for GVHD. Hepatitis C may be protective. High-dose steroids and CNI are ineffective in the treatment of GVHD after LT. CD2-blockers and TNF-α antagonists appear promising. We propose a diagnostic algorithm to assist clinicians in managing adults with GVHD after LT.

INTRODUCTION

Graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) is an infrequent complication after liver transplantation (LT), with an incidence of 0.5–2% 1–3. GVHD occurs as a result of donor immunocompetent cells recognizing recipient antigens as foreign and mounting an immune response. Grafts containing more immunocompetent donor lymphocytes, such as hematopoietic stem cell, bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell transplantations, are associated with a high incidence of GVHD. Among solid organ transplants, intestinal transplantation has the highest incidence of GVHD, followed by LT; with lower rates of GVHD after kidney, heart or pancreas transplantation.

The mortality rate for GVHD after LT has been reported to be up to 85%.1 In this article, we report a case series and a comprehensive review of the literature on GVHD after LT. The epidemiology, risk factors, clinical features, and treatment outcomes are described; and a diagnostic algorithm is proposed.

MATERIALS and METHODS

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics Case Series

Medical records of all patients diagnosed with GVHD after LT at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (UIHC) were reviewed. GVHD cases were identified from a prospectively maintained list of complications after LT. Diagnosis of GVHD was established with skin and gastrointestinal biopsies. Histologic grading of skin and gastrointestinal GVHD was also performed (see supplement). 4, 5

GVHD was documented histologically in all patients. Donor chimerism, using a quantitative assay of short tandem DNA repeats (STR) in the cells of the skin, gastrointestinal mucosa, peripheral blood and/or bone marrow, was recorded when available. This study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board.

Review of literature on GVHD after LT

A comprehensive search of the databases of biomedical literature (Medline and Embase) was performed from 1988 (first case report of GVHD after LT) to 2014. The search strategy is described in Appendix 1. All case reports and case series of GVHD after LT in adults were reviewed. Reference lists of published reports were searched to find additional reports. Data on patient demographics, clinical findings, management and outcomes were extracted. Data was extracted from the United Network for Organ Sharing database, until January 2015, for group comparisons between reported United States cases of GVHD after LT and all US LT patients.

Statistical Analysis

Observations are reported as frequencies, and central tendencies are expressed as mean or median with standard deviation and interquartile range, based on the distribution of data. Categorical variables are reported as number and percent frequency of occurrence. Categorical data were compared using Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate. All statistical testing was 2-sided and assessed for significance at the 5% level using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

UIHC Case Series

A total of 762 LT were performed in adults from 1988 to January 31st 2015. Five recipients (0.7%) developed GVHD. A summary of the case series at the University of Iowa has been provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with GVHD after liver transplantation at UIHC

| Year | Age | Sex | Etiology | DM | GVHD onset (days) | Involved systems (grade) | GVHD related death | Survival (days) | Treatment for GVHD | Peak serum ferritin (ng/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 73 | M | NASH | Yes | 65 | Skin (II) GI (I) BM |

Yes | 161 | High dose steroids, continued tacrolimus. | 2225 |

| 2011 | 66 | M | ALD, HCC | Yes | 46 | Skin (I) GI (IV) BM |

Yes | 79 | High dose steroids, basiliximab, IVIG and increased tacrolimus. | 20,333 |

| 2011 | 60 | M | ALD, HCV, HCC | Yes | 117 | Skin (II) BM |

Yes | 11 | Added ATG, increased tacrolimus, and continued mycophenolate. | 7232 |

| 2002 | 60 | M | ALD, Hemo chromatosis | Yes | 85 | Skin (II) GI (II) |

No | >10 years | High dose steroids, continued tacrolimus and mycophenolate. | 733 |

| 1996 | 65 | F | PBC | Yes | 15 | Skin BM |

Yes | 5 | High dose steroids, and continued tacrolimus. | NA |

UIHC: University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, GVHD: Graft-versus-host-disease, ALD: alcoholic liver disease; ATG: Anti-thymocyte globulin; BM: Bone marrow; DM: Diabetes mellitus; F: Female; GI: Gastrointestinal tract; HCC: Hepatocellular cancer; HCV: Hepatitis C; M: Male; F: Female, NA: Not available; NASH: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; PBC: Primary biliary cholangitis.

Case 1

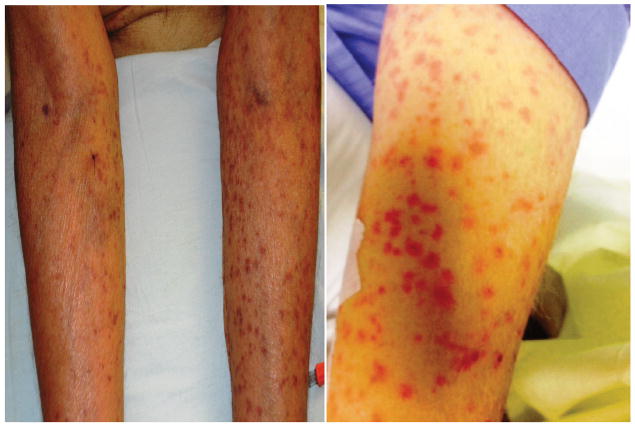

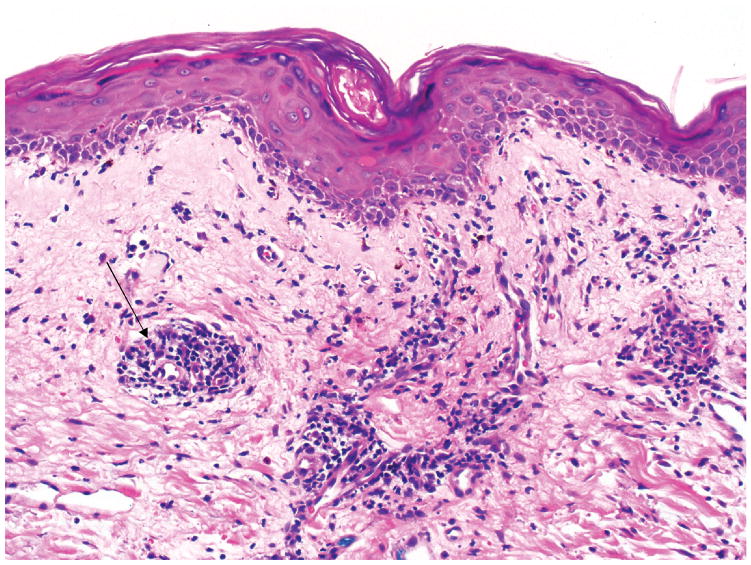

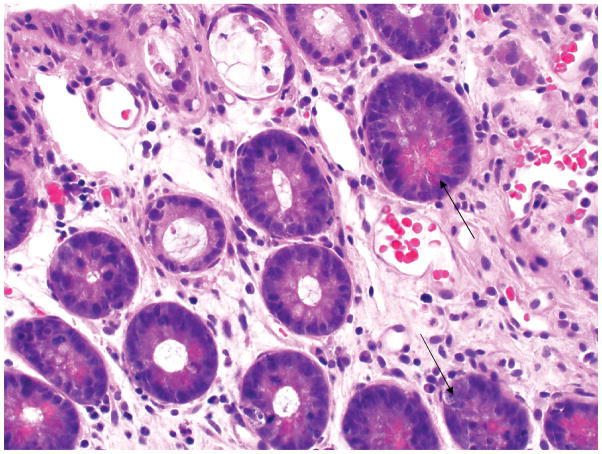

A 73 year-old diabetic man, with cirrhosis due to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), underwent LT in June 2014. He presented 60 days after LT with fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and maculopapular rash (Figure 1). White blood cell (WBC) count was 1600/mm3, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) 1280/mm3, hemoglobin 6.8 g/mm3, platelet count 108*103/mm3; and ferritin 2225 ng/mL. Skin biopsy showed vacuolar interface alteration of the dermal-epidermal junction, overlying lymphocytic infiltration, and scattered apoptotic keratinocytes (GVHD grade 2) (Figure 2). Colonoscopy showed normal colonic mucosa, but mucosal biopsies showed increased crypt epithelial apoptosis (GVHD grade 1) (Figure 3). STR analysis revealed 21%, 6% and 3% lymphocyte macrochimerism in the skin, colon and peripheral blood, respectively. He was started on methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg/day, and his tacrolimus level was kept at 8–12 ng/mL. His course was complicated by multiple infections (cytomegalovirus viremia, cryptosporidiosis of the gastrointestinal tract, and lobar pneumonia), all managed medically, while continuing methylprednisolone at 2 mg/kg/day. Rash, gastrointestinal symptoms, and pancytopenia resolved, and peripheral blood macrochimerism decreased to 1%. He was discharged on prednisone 80 mg/day for 2 weeks and 60 mg/day for 2 more weeks, before presenting with fever, vomiting and pancytopenia (WBC count 1,000/mm3). Colonoscopy showed inflamed ulcerated mucosa; biopsies showed abundant apoptotic crypt epithelial cells and crypt drop-out (GVHD grade 3). He was again treated with high-dose methylprednisolone, 2 mg/kg, while maintaining the same dose of calcineurin inhibitor (CNI). He developed pneumonia and septic shock and died 220 days after LT.

Figure 1.

Maculopapular skin rash in a patient with graft versus host disease after liver transplantation.

Figure 2.

Skin biopsy demonstrating perivascular mononuclear infiltrate (arrow) in the superficial dermis as well as vacuolar interface change, including scattered apoptotic keratinocytes (Grade 2 Graft Versus Host Disease).

Figure 3.

Ileal biopsy demonstrates apoptotic crypt epithelial cells (arrow) and degenerating crypts suggestive of graft versus host disease.

Case 2

A 65 year-old diabetic man underwent LT for alcoholic cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in March 2011. He presented 46 days after transplantation with maculopapular skin rash, fatigue, fever, diarrhea, weight loss, and modest leucopenia (WBC count 2300/mm3, ANC 1350/mm3). Ferritin was 799 ng/mL. Skin biopsy confirmed GVHD (grade 2). He was treated with methylprednisolone and tacrolimus dose increase. Skin and gastrointestinal symptoms improved, and WBC count rose to 6000/mm3. He was discharged on prednisone taper. Four weeks later, he returned with diarrhea, skin rash, septic arthritis (ankle), bacteremia, and WBC count of 900/mm3. Colonoscopy with biopsies showed extensive crypt dropout and denudation of epithelium (grade 4 GVHD). He had 41% donor lymphocytes in peripheral blood and 31% in the bone marrow. Ferritin was 20,333 ng/mL. Tacrolimus dose was decreased. Clinical features of GVHD worsened. Methylprednisolone was restarted; IVIG and the IL-1 antagonist, Anakinra, were added. He developed vancomycin-resistant enterococcal (VRE) bacteremia with septic shock and died 125 days after LT.

Case 3

A 60 year-old diabetic man, with cirrhosis and HCC from alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and chronic hepatitis C, underwent LT in November 2011. He presented 117 days after LT with maculopapular skin rash (GVHD grade 2), fever, altered mental status, pancytopenia (WBC 200/mm3, ANC 0, hemoglobin 8.1 g/dL, platelet count 111*103cells/mm3) and ferritin 7232 ng/mL. STR analysis of peripheral blood revealed 78% macrochimerism. Bone marrow biopsy was hypocellular, with 89% macrochimerism. He was treated with an interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor blocker (basiliximab), anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), methylprednisolone, and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG); and tacrolimus was increased to 12–16 ng/mL. Due to nonresponse to initial treatment, Anakinra was added, without improvement. He developed VRE bacteremia, septic shock and died 128 days after LT.

Case 4

A 60 year-old diabetic man, with cirrhosis from ALD and hemochromatosis, underwent LT in 2002. He presented with maculopapular skin rash (GVHD histologic grade 2) and diarrhea (GVHD histologic grade 2) 85 days after LT. CBC was normal. Peak serum ferritin was 733 ng/mL. He was treated with methylprednisolone, IVIG, and topical tacrolimus. Systemic tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil were continued at the same dosage. Skin rash and diarrhea resolved. Serum ferritin normalized. He was doing well at follow-up 10 years after LT.

Case 5

A 65 year-old diabetic woman with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) underwent LT in February 1996. Induction immunosuppression regimen included methylprednisolone and tacrolimus. Fourteen days after LT, she developed maculopapular skin rash, altered mental status, pancytopenia (WBC 100/mm3, platelets 17,000/mm3) and septic shock. Skin biopsy was consistent with GVHD. Histologic grading and STR analysis were not performed. She succumbed to septic shock within 5 days of presentation, before she could be started on treatment for GVHD.

A summary of the case series has been provided in Table 1.

Review of Literature on GVHD after LT

A total of 80 articles reported 1 or more case, with a total of 156 cases of GVHD in adult LT recipients. Characteristics of reported cases are summarized in Table 2. Mean age at LT was 55 years, and 67.3% were male. Median time to GVHD onset from LT was 28 days (interquartile range 21–38 days). The most common clinical features in patients with GVHD were skin rash (92%), followed by cytopenias (78%) and diarrhea (65%). HCC (34.7%) was the most common indication for LT in patients who developed GVHD, followed by alcoholic liver disease (22.9%) and acute or chronic hepatitis B (19.5%). The presenting organ involvement for all patients with GVHD in the world and in the US is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics of reported cases of acute GVHD after LT in the world literature, US literature, and of all adult liver transplants in UNOS database

| GVHD after LT (World literature) | GVHD after LT (US) | UNOS database1 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 156 | 66 | 119,701 | |

| Age: n (%) | ||||

| 18 – 35 | 28 (17.9) | 5 (7.6) | 9,133 (7.6) | <0.01 |

| 35 – 49 | 30 (19.2) | 7 (10.6) | 34,329 (28.7) | |

| 50 – 64 | 77 (49.4) | 43 (65.2) | 64,061 (53.5) | |

| ≥65 | 21 (13.5) | 11 (16.7) | 12,178 (10.2) | |

| Gender, male: n (%) | 105 (67.3) | 44 (66.7) | 84,030 (70.2) | 0.53 |

| Etiology of liver disease*: n (%) | ||||

| 1. Acute liver failure | 3 (2.5) | 1 (2.0) | 6,824 (5.7) | |

| 2. Alcoholic liver disease | 27 (22.9) | 12 (23.5) | 21,495 (18.0) | |

| 3. Chronic Hepatitis C | 16 (13.6) | 6 (11.8) | 35,812 (29.9) | |

| 4. Chronic hepatitis B | 23 (19.5) | 5 (9.8) | 5,168 (4.3) | |

| 5. Primary Sclerosing cholangitis | 9 (7.6) | 7 (13.7) | 7,153 (6.0) | |

| 6. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis | 12 (10.2) | 5 (9.8) | 5,754 (4.8) | |

| 7. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | 13 (11.1) | 9 (17.6) | 13,415 (11.2) | |

| 8. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 1,578 (1.3) | |

| 9. Autoimmune hepatitis | 4 (3.4) | 2 (3.9) | 3,802 (3.2) | |

| 10.Hemochromatosis | 3 (2.5) | 3 (5.9) | 749 (0.6) | |

| Presence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: n (%) | 41 (34.7) | 11 (21.6) | 15,542 (13.0) | |

| Presenting organ involvement+: n(%) | ||||

| 1. Skin only | 33 (31) | 11 (23) | ||

| 2. Bone Marrow only | 17 (16) | 10 (21) | ||

| 3. Skin + GI + BM | 17 (16) | 9 (19) | ||

| 4. Skin + GI | 14 (13.2) | 6 (13) | ||

| 5. Skin + BM | 14 (13.2) | 7 (14.5) | ||

| 6. GI only | 11 (10.4) | 5 (10.4) |

GVHD: graft-versus-host-disease; LT: liver transplantation; US: United States; UNOS: United network for organ sharing.

Etiology of liver disease was reported in 118 total cases, 51 of them were from USA.

Presenting organ involvement was reported in 106 cases.

Reported US GVHD cases were subtracted from the respective age and etiology categories in UNOS database for statistical analysis.

Data on outcome of GVHD management was reported in 138 patients; 73.2% died within 6 months of GVHD onset. There have been no prospective trials of treatment of GVHD after LT. This review found reports of treatment of GVHD after LT in 130 patients. In 8 patients (6.2%) immunosuppression was decreased6–11, while immunosuppression was intensified in 122 patients (93.8%). Six-month mortality was 70.5% in patients who had increased immunosuppression and 62.5% in patients with decreased immunosuppression. This difference was not statistically significant (p=0.68). The most frequently reported treatment regimen for GVHD after LT was high-dose steroids (ranging from 2 mg/kg/day to 20 mg/kg/day). The number of patients treated and mortality rate associated with various treatments regimens are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Combination immunosuppression regimens and outcomes of patients with GVHD after liver transplantation

| Treatment regimen | Number of patients | Mortality n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A. Steroid containing regimens | ||

| Steroids only*1, 9, 14, 27, 50, 66–75 | 25 | 21 (84) |

| Steroids + CNI dose increase13, 23, 76–80 | 8 | 6 (75) |

| Steroids + IVIG22, 80, 81 | 4 | 4 (100) |

| Steroids + Azathioprine12, 82, 83 | 3 | 3 (100) |

| Steroids ± OKT31, 11, 84–88 | 7 | 5 (71.4) |

| B. ATG containing regimens | ||

| ATG only*1, 14, 89, 90 | 4 | 3 (75) |

| ATG + steroids*1, 11, 27, 91–97 | 22 | 18 (81) |

| ATG + Steroids + CNI98, 99 | 3 | 3 (100) |

| C. IL-2 antagonist containing regimens | ||

| IL 2 antagonist + Steroids*17, 27, 72, 96, 100–103 | 12 | 7 (58) |

| IL 2 antagonist + Steroids + CNI23, 104 | 2 | 2 (100) |

| IL 2 antagonist + Steroids + ATG14, 15, 21, 105 | 4 | 4 (100) |

| D. Other treatment regimens | ||

| Alefacept + steroids + ATG16, 50, 51 | 7 | 2 (28) |

| TNF alpha inhibitors + steroids + ATG17, 106–108 | 4 | 1 (25) |

| Rituximab Steroids ± ATG ± IL 2 antagonist109–112 | 4 | 3 (75) |

No addition or dose increase of CNI was reported. GVHD: graft versus host disease; ATG: Anti-thymocyte globulin; CNI: calcineurin inhibitors; IL-2: interleukin-2; IVIG: Intravenous immunoglobulin; MLAG: Minnesota anti-lymphocyte globulin; OKT3: Muromonab-CD3; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

The common causes of death in patients with GVHD after LT were sepsis, multi-organ failure and gastrointestinal bleeding. In 61 cases (60.4%), sepsis was documented as cause of death. The causative organism was reported in 25 cases (41%); invasive aspergillosis was noted in 9 cases1, 9, 12–17 (36%), disseminated candidiasis in 7 (28%) (3 albicans, 1 kruseii, 1 glabrata and 2 unspecified species) 1, 9, 18, 19, enterococci in 7 (28%)1, 20–23 and Enterobacter in 2 (8%)1, 24.

There were 66 reported cases of GVHD after LT from the US and these were compared to all other LT recipients in the US, as accessed through the UNOS database (Table 2). A significant association between age and GVHD was evident, where patients with GVHD were older than 50-years (p<0.01). Gender was not a risk factor for development of GVHD. Higher GVHD incidence was noted in patients transplanted for HCC (21.6 % vs 13.0%), while chronic hepatitis C infection (HCV) was associated with a lower incidence of GVHD after LT, as compared to all other US patients in UNOS database (11.8% vs 29.9%) (Table 2).

There are 37 patients reported in the literature who survived GVHD after LT. The mean age of patients was 56.1 years, 83.3% were males, and mean time from LT to diagnosis of GVHD was 43.3 days (range 13–80). The etiology of liver disease was alcoholic liver disease in 43% of patients; HBV in 27%; NASH in 11%; HCV, PSC and A1AT in 5% each; with PBC and acute liver failure in 2% each. 50% of these patients presented with skin involvement only, 21% with bone marrow involvement only, and 18% with both skin and gastrointestinal involvement. The treatment regimens of patients who survived GVHD after LT are provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Treatment regimen for patients who survived GVHD after Liver transplantation.

| Treatment regimen | Number of patients (n) |

|---|---|

| A. Steroid containing regimens | |

| Steroids only7, 68, 69, 75 | 4 |

| Steroids + CNI dose increase23, 75, 113 | 3 |

| Steroids + OKT384, 87 | 2 |

| B. ATG containing regimens | |

| ATG only1 | 1 |

| ATG + steroids92, 94, 97 | 4 |

| ATG + Steroids + CNI98 | 1 |

| C. IL-2 antagonist containing regimens | |

| IL 2 antagonist + Steroids27, 101–103 | 5 |

| IL-2 antagonist + Steroids + ATG105 | 1 |

| D. Other treatment regimens | |

| Alefacept + steroids + ATG50, 51 | 5 |

| TNF alpha inhibitors + steroids + ATG106–108 | 3 |

| Rituximab + Steroids + CNI dose increase + IL 2 antagonist109 | 1 |

Immunosuppression was decreased in 3 patients who survived GVHD after liver transplantation. GVHD: graft versus host disease; ATG: Anti-thymocyte globulin; CNI: calcineurin inhibitors; IL-2: interleukin-2; OKT3: Muromonab-CD3; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

DISCUSSION

Risk Factors

This systematic review demonstrates an association between GVHD after LT with recipient age over 50-years. Additional risk factors reported in the literature include donor-recipient age difference greater than 20 years, younger donor age, any HLA class I match, and glucose intolerance.2, 25 Based on our results, GVHD may occur more frequently in patients transplanted for HCC and less frequently in patients transplanted for hepatitis C. Immune dysregulation plays a major role in the pathogenesis of HCC. Alterations in innate or adaptive immunity, for example a decrease in the CD4+ T lymphocyte function due to chronic inflammation (alcoholic or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis), chronic infection (viral hepatitis), or suppression of immunity (cirrhosis), may tolerance to tumor antigen and promote the development of HCC.26 Furthermore, HCC itself may cause immune system dysfunction.26 It is possible that the immune dysregulation in the recipient that originally led to the development of HCC, or alterations in the immune system caused by HCC, may predispose to alloreactivity and development of GVHD after LT.27, 28 HCV is known to inhibit T cell receptor-mediated signaling required for activation and effector functions of T cells.29 Whether HCV demonstrates the same effect on donor T-lymphocytes, thereby decreasing the incidence of GVHD, is unclear.

Clinical Features

Our review shows that GVHD usually develops 3 to 5 weeks after LT. Skin rash is erythematous, maculopapular, and can involve any part of the body including palms, soles, and the volar surfaces of extremities and trunk. Skin rashes may be subtle, nonpruritic, and not noticed by the patient. A very careful total-body skin exam in a well-lit room is recommended. Characteristic histologic features are vacuolar alteration at the dermo-epidermal junction, apoptosis of keratinocytes in the epidermis, and lymphocyte exocytosis (Figure 2).

GVHD can affect all 3 hematopoietic cell lineages. The alloreactive donor lymphocytes engraft and proliferate in the recipient bone marrow, with subsequent immune-mediated attack on hematopoietic stem cells. Cytopenia in the first few months after LT is common; infection (Herpes virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr virus and parvovirus B19) and medications (mycophenolate mofetil, valganciclovir, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) are the usual culprits. In GVHD, the presence of cytopenia may be a poor prognostic indicator, and sepsis associated with leucopenia is a commonly reported cause of death.

Gastrointestinal manifestations are common in GVHD. Diarrhea is a common symptom in solid organ transplant recipients; up to 10–13% of patients have diarrhea in the first 4 post-transplant months.30, 31 The common etiologies for diarrhea are infection (Clostridium difficile and cytomegalovirus colitis) and medications (mycophenolate mofetil, everolimus, sirolimus and tacrolimus).32 Endoscopic evidence for GVHD is provided by the presence of erythema, exudates and superficial ulceration of gastrointestinal mucosa. However, the sensitivity and specificity of endoscopic findings are sub-optimal to rule in or rule out GVHD; histopathology is necessary. Rectosigmoid biopsies are most sensitive.33, 34 In GVHD, histopathology shows increased crypt epithelial apoptosis, crypt loss and neutrophilic infiltration. Apoptosis of epithelial cells is induced by activated donor cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. It is, however, important to note that epithelial apoptosis can be seen after LT from etiologies other than GVHD, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis, mycophenolate-induced colitis and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. CMV colitis can be diagnosed by immunohistochemical demonstration of CMV viral inclusions. Mycophenolate-induced colitis can be differentiated from GVHD by presence of more than 15 eosinophils per high power field, lack of endocrine cell aggregates in lamina propria, and lack of apoptotic microabscesses.35

Donor lymphocyte microchimerism (<1% donor lymphocyte chimerism) is often seen in liver transplant recipients; it is postulated that microchimerism is important for immune tolerance and graft acceptance by the host.3, 36–38 In contrast, patients with GVHD have donor lymphocyte macrochimerism (>1% donor lymphocyte chimerism) in recipient tissues (skin, gastrointestinal mucosa, peripheral blood), ranging from 1% to 80%.3, 19, 38-45 However, donor lymphocyte macrochimerism in peripheral blood alone doesn’t confirm the diagnosis of GVHD.46 Macrochimerism in a patient with clinical and histological features suggestive of GVHD (involvement of the skin, bone marrow and/or gastrointestinal tract) should be considered diagnostic of GVHD. Confirmation of macrochimerism should not be required to start treatment for GVHD, as it may take several days for results to be obtained. Monitoring donor lymphocyte macrochimerism in target organs and peripheral blood may be helpful, even after resolution of symptoms, as persistence of macrochimerism may suggest incomplete resolution of GVHD and a high risk of relapse with tapering of immunosuppression.

Ferritin level was checked in 4 of the UIHC GVHD patients and was markedly elevated in all. The mean peak ferritin in patients who died of GVHD in our case series was 9930 ng/mL (range: 2225–20,333) while the peak ferritin in the surviving patient was 733 ng/mL. Marked hyperferritinemia in GVHD after LT has not been previously reported. Though serum ferritin is a nonspecific acute phase reactant, an extreme elevation of ferritin level is seen only in a few conditions.47 Cytokines released by activated donor lymphocytes, and the associated inflammatory response, is the likely mechanism behind hyperferritinemia in GVHD.

Treatment and Outcome

Fourteen of the 17 reported treatment regimens for GVHD after LT were associated with mortality rates over 70%, including all regimens that included high dose intravenous steroids only or an increase in CNI dose (with both tacrolimus and cyclosporine). Only 3 reported treatment regimens for GVHD after LT yielded mortality rates less than 60%. These regimens, used in a small number of patients, included IL-2 antagonists (basiliximab or daclizumab), the CD2 inhibitor alefacept, or TNF-α inhibitors.

The efficacy of IL-2 antagonists in case series of patients with GVHD after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has shown promise, with survival of 40–60%.48, 49 Though the survival rate may be better with IL-2 antagonists compared to other reported regimens for GVHD after LT, mortality rate is still substantial.

Starting high-dose steroids upon diagnosis of GVHD after LT, with addition of Alefacept and ATG when the patient develops pancytopenia 50, 51, was shown to result in the immediate rebound of bone marrow function. Alefacept is a fusion protein that binds to the lymphocyte antigen CD2, inhibits the interaction of CD2 and human leukocyte function antigen-3 (LFA-3), thereby preventing the activation of CD4 and CD8 T-lymphocytes; while ATG eliminates the activated effector T cells. Alefacept also showed potential benefit for treatment of GVHD in bone marrow transplantation recipients.52 Unfortunately, Alefacept, has been discontinued by the manufacturers, without any safety or FDA regulation concerns.53 Sipilizumab is a similar agent that targets the CD2 receptor on T-lymphocytes and natural killer cells. A phase I trial of sipilizumab for treatment of GVHD after bone marrow transplantation in children reported a good response, but a higher incidence of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder was noted, raising safety concerns.54

Initial studies of patients with steroid-refractory GVHD post-HSCT showed promising results with the use of the TNF α inhibitor, infliximab.55, 56 Recent studies, including a phase-III study in patients with GVHD after HSCT, showed no benefit of addition of infliximab to methylprednisolone compared to methylprednisolone alone.57 However, higher response rates have been reported with etanercept in patients with GVHD after HSCT.58–62 Etanercept, unlike infliximab, does not lead to antibody-dependent cytotoxicity and induction of apoptosis of TNF-α-positive monocytes, possibly decreasing risk of infection compared to infliximab. The literature on the use of TNF-α inhibitors in GVHD after LT is limited. However, based on the high mortality with the majority of reported regimens, the 75% survival among the 4 patients treated with TNF-α-inhibition, and the data on etanercept in HSCT patients with GVHD, etanercept or other TNF-α antagonists could be useful as a second line agent in patients with GVHD after LT who are steroid-refractory or dependent.

The major drawback of increasing immunosuppression in patients with GVHD after LT is the high risk of death from sepsis. Enterobacter septicemia, invasive aspergillosis and disseminated Candida infection are common causes of death with GVHD. A study performed on patients with GVHD post-HSCT showed a significant increase in the risk of non-Candida invasive fungal infections with the use of infliximab.63 Thus, vigilance for development of infection and timely use of antibiotics and antifungal agents is very important. Empiric use of antibiotics to cover gram negatives and anaerobic bacteria, especially VRE, and antifungal prophylaxis, appears reasonable. CMV and Pneumocystis prophylaxis is advised during high-level immunosuppression. The role of granulocyte-monocyte colony stimulating factor in GVHD is unclear, but may be given in patients with marked neutropenia.

In patients with gastrointestinal GVHD after HSCT, a step-wise oral “GVHD diet” may be beneficial.64 Severe protein-calorie malnutrition as a result of protein losing enteropathy and malabsorption is treated with 1.5 g/kg/day of protein. In addition, these patients may develop vitamin, micronutrient and essential trace element (including magnesium and zinc) deficiencies. In patients with massive diarrhea, total parenteral nutrition may be needed. When diarrhea is less than 500 mL/day, oral foods are introduced in a step-wise manner.64 This approach may be beneficial in patients with GVHD after LT, though no data is available.

Extracorporeal photopheresis, an apheresis and photodynamic therapy, has shown promising results in the treatment of patients with GVHD after HSCT.65 It is an immunomodulator therapy which involves collection of peripheral blood mononuclear cells, irradiation of these leucocyte cells in-vitro by ultraviolet A in the presence of the drug 8-methoxypsoralen, followed by re-infusion of the cells into the patient. The main advantage of this therapy is the absence of generalized immunosuppression, thereby decreasing the risk of developing life-threatening infections. Further trials are needed before establishing extracorporeal photopheresis as a treatment option for GVHD.

Proposed diagnostic algorithm and treatment recommendations

How then do we diagnose and treat our next patient with GVHD after LT? Based on our interpretation of currently available data, we propose a diagnostic algorithm (Figure 4) for GVHD after LT. Patients who have symptoms involving the most commonly involved organ systems in GVHD, namely skin, gastrointestinal tract and bone marrow, should be evaluated for GVHD. Patients with maculopapular skin rash post-LT should undergo skin biopsy, as it is a simple procedure with low morbidity, and the histology can be diagnostic of GVHD. In patients who present with diarrhea or pancytopenia after LT, the most common causes of these symptoms should be ruled out. If symptoms persist, a colonoscopy with mucosal biopsies should be performed to screen for GVHD changes. Strong treatment recommendations cannot be made due to the absence of prospective studies and due to the high mortality rates for the majority of reported treatment regimens. Multidisciplinary involvement, with hematologists, infectious disease specialists and immunologists, is essential in the management of this complex condition.

Figure 4.

Proposed diagnostic algorithm for GVHD in liver transplantation recipients.

Study limitations

The proposed diagnostic algorithm is based on limited evidence. Comparisons of treatment regimen mortality rates are based on small cohort sizes and do not take into consideration other patient- or disease-related factors which may affect mortality rates. With only summary data available from the UNOS database, comparisons with reported US patients with GVHD are limited to univariate tests of association. Clearly, all US cases of GVHD after LT in the US have not been reported, and occurrence of GVHD after LT is not reported in the UNOS database, limiting the interpretation of statistical analysis.

CONCLUSIONS

GVHD after LT is infrequent, but is associated with a very high mortality rate. Most patients develop GVHD in 3–5 weeks after LT. GVHD may occur more often in LT patients over 50 years of age and who have diabetes. When reported US GVHD cases were compared to all LT patients in the UNOS database, HCC appeared to be over-represented, and HCV was under-represented. High-dose steroids alone, or combined with increasing CNI dose, are not effective treatment regimens. High-dose steroids combined with IL-2 antagonists or TNF-α inhibitors may be more promising approaches, though experience is limited. Donor macrochimerism and serum ferritin may be helpful for monitoring response to treatment. The participation of multiple institutions in a working group to prospectively study GVHD after LT, along with obligatory reporting of GVHD cases to UNOS, is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grants and financial support: This project is in part supported by R56 AI 116715 from the NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases). No other funding received for the manuscript.

List of Abbreviations

- ALD

Alcoholic liver disease

- ANC

Absolute neutrophil count

- ATG

Anti-thymocyte globulin

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- CNI

Calcineurin inhibitor

- GVHD

Graft versus host disease

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HSCT

Hematopoietic stem cell transplant

- IL

Interleukin

- IVIG

Intravenous immunoglobulin

- LT

Liver transplantation

- NASH

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- PBC

Primary biliary cholangitis

- STR

Short tandem repeats

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- UIHC

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- US

United States

- VRE

Vancomycin resistant enterococci

- WBC

White blood cell

Footnotes

No other financial disclosures.

No conflicts of interest.

Presented in part at DDW 2015, Washington D.C, USA

Author contributions

1. Arvind R Murali: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, statistical analysis

2. Subhash Chandra: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, statistical analysis

3. Zoe Stewart: critical revision of manuscript

4. Bruce R Blazar: critical revision of manuscript

5. Umar Farooq: critical revision of manuscript

6. M Nedim Ince: obtained funding, critical revision of manuscript

7. Jeffrey Dunkelberg: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, critical revision of manuscript, study supervision.

Contributor Information

Arvind Rangarajan Murali, Email: arvind-murali@uiowa.edu, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Subhash Chandra, Email: subhash-chandra@uiowa.edu, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Zoe Stewart, Email: zoe-stewart@uiowa.edu, Department of Surgery, Division of Transplantation & Hepatobiliary Surgery, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Bruce R Blazar, Email: blaza001@umn.edu, Division of Blood and Bone Marrow Transplantation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Umar Farooq, Email: umar-farooq@uiowa.edu, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Bone Marrow Transplant, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

M Nedim Ince, Email: m-nedim-ince@uiowa.edu, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Jeffrey Dunkelberg, Email: jeffrey-dunkelberg@uiowa.edu, Department of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

References

- 1.Smith DM, Agura E, Netto G, et al. Liver transplant-associated graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation. 2003;75:118–26. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200301150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan EY, Larson AM, Gernsheimer TB, et al. Recipient and donor factors influence the incidence of graft-vs.-host disease in liver transplant patients. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:516–22. doi: 10.1002/lt.21082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor AL, Gibbs P, Sudhindran S, et al. Monitoring systemic donor lymphocyte macrochimerism to aid the diagnosis of graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;77:441–6. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000103721.29729.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerner KG, Kao GF, Storb R, et al. Histopathology of graft-vs.-host reaction (GvHR) in human recipients of marrow from HL-A-matched sibling donors. Transplant Proc. 1974;6:367–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sale GE, Shulman HM, McDonald GB, et al. Gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease in man. A clinicopathologic study of the rectal biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol. 1979;3:291–9. doi: 10.1097/00000478-197908000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chinnakotla S, Smith DM, Domiati-Saad R, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation: role of withdrawal of immunosuppression in therapeutic management. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:157–61. doi: 10.1002/lt.20982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao PJ, Leng XS, Wang D, et al. Graft versus host disease after liver transplantation: a case report. Frontiers of medicine in China. 2010;4:469–72. doi: 10.1007/s11684-010-0120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nah YW, Nam CW, Park SE, et al. Graft versus host disease following liver transplantation. Liver Transplantation. Conference: 16th Annual International Congress of the International Liver Transplantation Society Hong Kong China. Conference Start; 2010; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts JP, Ascher NL, Lake J, et al. Graft vs. host disease after liver transplantation in humans: a report of four cases. Hepatology. 1991;14:274–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotru A, Gupta M, Maloo M, et al. Graft versus host disease following liver transplantation - A diagnostic dilemma. HPB. 2010;12:379. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohler S, Pascher A, Junge G, et al. Graft versus host disease after liver transplantation - a single center experience and review of literature. Transplant Int. 2008;21:441–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romagnuolo J, Jewell LD, Kneteman NM, et al. Graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation complicated by systemic aspergillosis with pancarditis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000;14:637–40. doi: 10.1155/2000/678043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schrager JJ, Vnencak-Jones CL, Graber SE, et al. Use of short tandem repeats for DNA fingerprinting to rapidly diagnose graft-versus-host disease in solid organ transplant patients. Transplantation. 2006;81:21–5. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000190431.94252.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perri R, Assi M, Talwalkar J, et al. Graft vs. host disease after liver transplantation: a new approach is needed. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1092–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghali MP, Talwalkar JA, Moore SB, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;83:365–6. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000245702.27300.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogulj IM, Deeg J, Lee SJ. Acute graft versus host disease after orthotopic liver transplantation. Journal of Hematology and Oncology. 2012:5. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-5-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Blank G, Li J, Kratt T, et al. Treatment of liver transplant graft-versus-host disease with antibodies against tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Exp Clin Transplant. 2013;11:68–71. doi: 10.6002/ect.2012.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollack MS, Speeg KV, Callander NS, et al. Severe, late-onset graft-versus-host disease in a liver transplant recipient documented by chimerism analysis. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:28–31. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohler S, Pascher A, Junge G, et al. Graft versus host disease after liver transplantation - a single center experience and review of literature. Transpl Int. 2008;21:441–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connors J, Drolet B, Walsh J, et al. Morbilliform eruption in a liver transplantation patient. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1161–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meves A, el-Azhary RA, Talwalkar JA, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation diagnosed by fluorescent in situ hybridization testing of skin biopsy specimens. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2006;55:642–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Post GR, Black JS, Cortes GY, et al. The utility of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis in diagnosing graft versus host disease following orthotopic liver transplant. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2011;41:188–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandra SMA, Dunkelberg J, Stewart Z. Graft Versus Host Disease Post-Liver Transplantation: A Single Center Gastroenterology. Iran J Med Sci. 2015;148:S1042–1043. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Au WY, Lo CM, Hawkins BR, et al. Evans' syndrome complicating chronic graft versus host disease after cadaveric liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;72:527–8. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200108150-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elfeki MGP, Pungpapong S, Nguyen J, Harnois D. Graft-Versus-Host Disease After Orthotopic Liver Transplantation: Multivariate Analysis of Risk Factors. Am J Transplant. 2015;15 doi: 10.1111/ctr.12627. Abstract 81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sachdeva M, Chawla YK, Arora SK. Immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2080–90. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i17.2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor AL, Gibbs P, Bradley JA. Acute graft versus host disease following liver transplantation: the enemy within. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:466–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald-Hyman C, Turka LA, Blazar BR. Advances and challenges in immunotherapy for solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:280rv2. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa6853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhattarai N, McLinden JH, Xiang J, et al. Conserved Motifs within Hepatitis C Virus Envelope (E2) RNA and Protein Independently Inhibit T Cell Activation. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005183. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altiparmak MR, Trablus S, Pamuk ON, et al. Diarrhoea following renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2002;16:212–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2002.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong NA, Bathgate AJ, Bellamy CO. Colorectal disease in liver allograft recipients -- a clinicopathological study with follow-up. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:231–6. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ginsburg PM, Thuluvath PJ. Diarrhea in liver transplant recipients: etiology and management. Liver Transplantation. 2005;11:881–90. doi: 10.1002/lt.20500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross WA, Ghosh S, Dekovich AA, et al. Endoscopic biopsy diagnosis of acute gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease: rectosigmoid biopsies are more sensitive than upper gastrointestinal biopsies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:982–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson B, Salzman D, Steinhauer J, et al. Prospective endoscopic evaluation for gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease: determination of the best diagnostic approach. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:371–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Star KV, Ho VT, Wang HH, et al. Histologic features in colon biopsies can discriminate mycophenolate from GVHD-induced colitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1319–28. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31829ab1ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood K, Sachs DH. Chimerism and transplantation tolerance: cause and effect. Immunol Today. 1996;17:584–7. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(96)10069-4. discussion 588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Starzl TE, Demetris AJ, Murase N, et al. Cell migration, chimerism, and graft acceptance. Lancet. 1992;339:1579–82. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91840-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Domiati-Saad R, Klintmalm GB, Netto G, et al. Acute graft versus host disease after liver transplantation: patterns of lymphocyte chimerism. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2968–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogulj IM, Deeg J, Lee SJ. Acute graft versus host disease after orthotopic liver transplantation. J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:50. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-5-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meves A, el-Azhary RA, Talwalkar JA, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation diagnosed by fluorescent in situ hybridization testing of skin biopsy specimens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:642–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mawad R, Hsieh A, Damon L. Graft-versus-host disease presenting with pancytopenia after en bloc multiorgan transplantation: case report and literature review. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:4431–3. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Key T, Taylor CJ, Bradley JA, et al. Recipients who receive a human leukocyte antigen-B compatible cadaveric liver allograft are at high risk of developing acute graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation. 2004;78:1809–11. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000145523.08548.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gulbahce HE, Brown CA, Wick M, et al. Graft-vs-host disease after solid organ transplant. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;119:568–73. doi: 10.1309/395B-X683-QFN6-CJBC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chinnakotla S, Smith DM, Domiati-Saad R, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation: role of withdrawal of immunosuppression in therapeutic management. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:157–61. doi: 10.1002/lt.20982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaib E, Silva FD, Figueira ER, et al. Graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:1115–8. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000600035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yao GL, Li W, Liu AB, et al. The experimental results of GVHD following orthotropic liver transplantation. Chung Hua Kan Tsang Ping Tsa Chih. 2009;17:856–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosario C, Zandman-Goddard G, Meyron-Holtz EG, et al. The hyperferritinemic syndrome: macrophage activation syndrome, Still's disease, septic shock and catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. BMC Med. 2013;11:185. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Przepiorka D, Kernan NA, Ippoliti C, et al. Daclizumab, a humanized anti-interleukin-2 receptor alpha chain antibody, for treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2000;95:83–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Massenkeil G, Rackwitz S, Genvresse I, et al. Basiliximab is well tolerated and effective in the treatment of steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;30:899–903. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eghtesad B, Askar M, Bollinger J, et al. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) following liver transplantation (LT): Comparison of two eras. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:126. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stotler CJ, Eghtesad B, Hsi E, et al. Rapid resolution of GVHD after orthotopic liver transplantation in a patient treated with alefacept. Blood. 2009;113:5365–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-207431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shapira MY, Resnick IB, Dray L, et al. A new induction protocol for the control of steroid refractory/dependent acute graft versus host disease with alefacept and tacrolimus. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:61–7. doi: 10.1080/14653240802644669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.National Psoriasis foundation APUSI. Amevive (alefacept) voluntarily discontinued in the US. Astellas Medical Information Department; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brochstein JA, Grupp S, Yang H, et al. Phase-1 study of siplizumab in the treatment of pediatric patients with at least grade II newly diagnosed acute graft-versus-host disease. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14:233–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2009.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang J, Cheuk DK, Ha SY, et al. Infliximab for steroid refractory or dependent gastrointestinal acute graft-versus-host disease in children after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:771–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2012.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kobbe G, Schneider P, Rohr U, et al. Treatment of severe steroid refractory acute graft-versus-host disease with infliximab, a chimeric human/mouse antiTNFalpha antibody. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:47–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Couriel DR, Saliba R, de Lima M, et al. A phase III study of infliximab and corticosteroids for the initial treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1555–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kennedy GA, Butler J, Western R, et al. Combination antithymocyte globulin and soluble TNFalpha inhibitor (etanercept) +/− mycophenolate mofetil for treatment of steroid refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:1143–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Busca A, Locatelli F, Marmont F, et al. Recombinant human soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor fusion protein as treatment for steroid refractory graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:45–52. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park JH, Lee HJ, Kim SR, et al. Etanercept for steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Korean J Intern Med. 2014;29:630–6. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2014.29.5.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uberti JP, Ayash L, Ratanatharathorn V, et al. Pilot trial on the use of etanercept and methylprednisolone as primary treatment for acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:680–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levine JE, Paczesny S, Mineishi S, et al. Etanercept plus methylprednisolone as initial therapy for acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2008;111:2470–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marty FM, Lee SJ, Fahey MM, et al. Infliximab use in patients with severe graft-versus-host disease and other emerging risk factors of non-Candida invasive fungal infections in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: a cohort study. Blood. 2003;102:2768–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van der Meij BS, de Graaf P, Wierdsma NJ, et al. Nutritional support in patients with GVHD of the digestive tract: state of the art. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:474–82. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Calore E, Marson P, Pillon M, et al. Treatment of Acute Graft-versus–Host Disease in Childhood with Extracorporeal Photochemotherapy/Photopheresis: The Padova Experience. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:1963–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Collins RH, Jr, Cooper B, Nikaein A, et al. Graft-versus-host disease in a liver transplant recipient. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:391–2. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-5-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mazzaferro V, Andreola S, Regalia E, et al. Confirmation of graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation by PCR HLA-typing. Transplantation. 1993;55:423–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Knox KS, Behnia M, Smith LR, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease of the lung after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:968–71. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.35552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nemoto T, Kubota K, Kita J, et al. Unusual onset of chronic graft-versus-host disease after adult living-related liver transplantation from a homozygous donor. Transplantation. 2003;75:733–6. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000053401.91094.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schoniger-Hekele M, Muller C, Kramer L, et al. Graft versus host disease after orthotopic liver transplantation documented by analysis of short tandem repeat polymorphisms. Digestion. 2006;74:169–73. doi: 10.1159/000100500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sun B, Zhao C, Xia Y, et al. Late onset of severe graft-versus-host disease following liver transplantation. Transplant Immunol. 2006;16:250–3. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang B, Lu Y, Yu L, et al. Diagnosis and treatment for graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation: two case reports. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:1696–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guo ZY, He XS, Wu LW, et al. Graft-verse-host disease after liver transplantation: A report of two cases and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:974–979. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jeanmonod P, Hubbuch M, Grunhage F, et al. Graft-versus-host disease or toxic epidermal necrolysis: diagnostic dilemma after liver transplantation. Transplant Infect Dis. 2012;14:422–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2012.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mataluni G, Mangiardi M, Rainone M, et al. Central and peripheral nervous system involvement as a manifestation of graft versus host disease after liver transplantation: Case report. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2013;18:S20. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dumortier J, Souraty P, Bernard P, et al. Graft versus host disease following liver transplantation: Favorable outcome after conversion to tacrolimus. [French] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2003;27:561–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Soejima Y, Shimada M, Suehiro T, et al. Graft-versus-host disease following living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:460–4. doi: 10.1002/lt.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hossain MS, Roback JD, Pollack BP, et al. Chronic GvHD decreases antiviral immune responses in allogeneic BMT. Blood. 2007;109:4548–56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yilmaz M, Ozdemir F, Akbulut S, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:1751–3. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen XB, Yang J, Xu MQ, et al. Unsuccessful treatment of four patients with acute graft-vs-host disease after liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:84–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Whalen JG, Jukic DM, English JC., 3rd Rash and pancytopenia as initial manifestations of acute graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:908–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schmuth M, Vogel W, Weinlich G, et al. Cutaneous lesions as the presenting sign of acute graft-versus-host disease following liver transplantation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:901–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Au WY, Ma SK, Kwong YL, et al. Graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation: documentation by fluorescent in situ hybridisation and human leucocyte antigen typing. Clin Transplant. 2000;14:174–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2000.140213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Redondo P, Espana A, Herrero JI, et al. Graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:314–7. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70184-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sanchez-Izquierdo JA, Lumbreras C, Colina F, et al. Severe graft versus host disease following liver transplantation confirmed by PCR-HLA-B sequencing: report of a case and literature review. Hepato-Gastroenterol. 1996;43:1057–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Burt M, Jazwinska E, Lynch S, et al. Detection of circulating donor deoxyribonucleic acid by microsatellite analysis in a liver transplant recipient. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2:391–4. doi: 10.1002/lt.500020511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.PAIZIS G, TAIT BD, ANGUS PW, et al. Successfid resolution of severe graft versus host disease after liver transplantation correlating with disappearance of donor DNA fkorn the peripheral blood. Aust NZ J Med. 1998;28:830–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1998.tb01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Neumann UP, Kaisers U, Langrehr JM, et al. Fatal graft-versus-host-disease: a grave complication after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:3616–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.DePaoli AM, Bitran J. Graft-versus-host disease and liver transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:170–1. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-2-170_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hara H, Ohdan H, Tashiro H, et al. Differential diagnosis between graft-versus-host disease and hemophagocytic syndrome after living-related liver transplantation by mixed lymphocyte reaction assay. J Invest Surg. 2004;17:197–202. doi: 10.1080/08941930490471966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chiba T, Yokosuka O, Goto S, et al. Clinicopathological features in patients with hepatic graft-versus-host disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:1849–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Burdick JF, Vogelsang GB, Smith WJ, et al. Severe graft-versus-host disease in a liver-transplant recipient. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:689–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198803173181107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pageaux GP, Perrigault PF, Fabre JM, et al. Lethal acute graft-versus-host disease in a liver transplant recipient: relations with cell migration and chimerism. Clin Transplant. 1995;9:65–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aziz H, Trigo P, Lendoire J, et al. Successful treatment of graft-vs-host disease after a second liver transplant. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:2891–2. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00857-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Merhav HJ, Landau M, Gat A, et al. Graft versus host disease in a liver transplant patient with hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:1890–1. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(99)00141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hanaway M, Buell J, Musat A, et al. Graft-Versus-Host Disease in Solid Organ Transplantation. Graft. 2001;4:205. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lehner F, Becker T, Sybrecht L, et al. Successful outcome of acute graft-versus-host disease in a liver allograft recipient by withdrawal of immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2002;73:307–10. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200201270-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schulman JM, Yoon C, Schwarz J, et al. Absence of peripheral blood chimerism in graft-vs-host disease following orthotopic liver transplantation: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e492–8. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Calmus Y. Graft-versus-host disease following living donor liver transplantation: High risk when the donor is HLA-homozygous. J Hepatol. 2004;41:505–507. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Merle C, Blanc D, Flesch M, et al. A picture of epidermal necrolysis after hepatic allograft. Etiologic aspects. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1990;117:635–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rinon M, Maruri N, Arrieta A, et al. Selective immunosuppression with daclizumab in liver transplantation with graft-versus-host disease. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:109–10. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02828-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sudhindran S, Taylor A, Delriviere L, et al. Treatment of graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation with basiliximab followed by bowel resection. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1024–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Husova L, Mejzlik V, Jedlickova H, et al. Graft-versus-host disease as an unusual complication following liver transplant. [Czech] Gastroenterologie a Hepatologie. 2012;66:109–115. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chaman JC, Padilla PM, Rondon CF, et al. Graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation in a partial monosomy 11q of chromosoma 11: A case report. Liver Transpl. 2013;(1):S181. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lu Y, Wu LQ, Zhang BY, et al. Graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation: successful treatment of a case. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:3784–6. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.03.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Piton G, Larosa F, Minello A, et al. Infliximab treatment for steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease after orthotopic liver transplantation: a case report. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:682–5. doi: 10.1002/lt.21793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Xu X, Zhou L, Ling Q, et al. Successful management of graft-versus-host disease after liver transplantation with Korean red ginseng based regimen. Liver Transpl; Conference: 16th Annual International Congress of the International Liver Transplantation Society Hong Kong China. Conference Start; 2010; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Thin L, Macquillan G, Adams L, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease after liver transplant: novel use of etanercept and the role of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors. Liver Transp. 2009;15:421–6. doi: 10.1002/lt.21704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Grosskreutz C, Gudzowaty O, Shi P, et al. Partial HLA matching and RH incompatibility resulting in graft versus host reaction and Evans syndrome after liver transplantation. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:599–601. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mawad R, Hsieh A, Damon L. Graft-versus-host disease presenting with pancytopenia after en bloc multiorgan transplantation: case report and literature review. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:4431–3. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Young AL, Leboeuf NR, Tsiouris SJ, et al. Fatal disseminated Acanthamoeba infection in a liver transplant recipient immunocompromised by combination therapies for graft-versus-host disease. Transplant Infect Dis. 2010;12:529–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2010.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cheung CYM, Leung AYH, Chan SC, et al. Fatal graft-versus-host disease after unrelated cadaveric liver transplantation due to donor/recipient human leucocyte antigen matching. Inten Med J. 2014;44:425–426. doi: 10.1111/imj.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hassan G, Khalaf H, Mourad W. Dermatologic complications after liver transplantation: a single–center experience. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:1190–4. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.