Abstract

AKT plays a pivotal role in driving the malignant phenotype of many cancers, including high-risk neuroblastoma (HR-NB). AKT signaling, however, is active in normal tissues, raising concern about excessive toxicity from its suppression. The oral AKT inhibitor perifosine showed tolerable toxicity in adults and in our phase I trial in children with solid tumors (clinicaltrials.gov NCT00776867). We now report on the HR-NB experience. HR-NB patients received perifosine 50–75mg/m2/day after a loading dose of 100–200mg/m2 on day 1, and continued on study until progressive disease. The 27 HR-NB patients included three treated for primary refractory disease and 24 with disease resistant to salvage therapy after 1–5 (median 2) relapses; only one had MYCN-amplified HR-NB. Pharmacokinetic studies showed μM concentrations consistent with cytotoxic levels in preclinical models. Nine patients (all MYCN-non-amplified) remained progression-free through 43+ to 74+ (median 54+) months from study entry, including the sole patient to show a complete response and eight patients who had persistence of abnormal 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine skeletal uptake but never developed progressive disease. Toxicity was negligible in all 27 patients, even with the prolonged treatment (11-to-62 months, median 38) in the nine long-term progression-free survivors. The clinical findings 1) confirm the safety of therapeutic serum levels of an AKT inhibitor in children; 2) support perifosine for MYCN-non-amplified HR-NB as monotherapy after completion of standard treatment or combined with other agents (based on preclinical studies) to maximize antitumor effects; and 3) highlight the welcome possibility that refractory or relapsed MYCN-non-amplified HR-NB is potentially curable.

Keywords: AKT, receptor tyrosine kinases, protein kinase B, PI3K pathway, alkylphospholipid

INTRODUCTION

The serine-threonine kinase AKT (also called protein kinase B) plays a pivotal role in the phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase (PI3K) pathway that, when aberrantly activated, drives the malignant phenotype of most types of cancers.1, 2 This pathway, however, is fundamental in many physiologic processes in normal tissues, raising concern about excessive toxicity from its suppression.2 Perifosine, which is a synthetic alkylphospholipid that inhibits AKT, proved to have modest toxicity in adults with solid tumors plus good oral bioavailability.3, 4 To assess toxicity in children, a pediatric phase I trial of perifosine monotherapy for resistant or relapsed solid tumors was initiated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). After a satisfactory toxicity profile and a safe dosage were identified, the trial was amended5 to enroll a separate cohort of patients with high-risk neuroblastoma (HR-NB) in order to assess efficacy specifically regarding this most common of pediatric extracranial solid tumors. In addition to encouraging preliminary clinical findings with HR-NB in the phase I trial, several observations, as recently summarized,5–7 supported a focus on HR-NB patients: 1) a plethora of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) mediate the clinical behavior of NB via the PI3K/AKT pathway;8–12 2) aberrant activation of AKT is associated with poor outcome in HR-NB patients;13 3) inhibitors of the PI3K/AKT signaling axis impair growth of NB;12–14 and 4) perifosine is cytotoxic in μM concentrations in preclinical studies using NB cell lines.14 We now report on the HR-NB experience.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This report covers all NB patients treated (2009–2014) on the MSKCC perifosine monotherapy protocol 08–091 (clinicaltrials.gov NCT00776867). There were no limitations regarding prior therapy. Eligibility criteria included: age ≤21 years; refractory or relapsed disease after standard therapy and documented ≥3 weeks after chemotherapy; absolute neutrophil count ≥1000/μl at least 24 hours after a dose of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; platelet count ≥75,000/μl at least one week without a platelet transfusion; liver function enzymes ≤3x the upper limit of normal; total bilirubin ≤2.0 mg/dl; and serum creatinine ≤1.5x the upper limit of normal. Informed written consents for treatment and tests were obtained according to MSKCC Institutional Review Board rules.

Study design

The primary objective of this phase I trial for pediatric patients with solid tumors was to identify the maximum tolerated dosage (MTD) of perifosine. Given the availability of perifosine only in 50 mg tablets, treatment dose levels were based on body surface area. Patients received a loading dose of oral perifosine on day 1, followed by maintenance. Dose level one corresponded to ~25 mg/m2/day; increments in dose levels were 25 mg/m2/day. Patients could continue taking perifosine on study until emergence of either progressive disease (PD) or dose-limiting toxicity by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 3.0. Five dose levels were investigated. No MTD was identified.

In a phase Ib expansion cohort, HR-NB patients were treated at dose level 3 for an evaluation of the anti-NB activity of perifosine monotherapy. This dose level was chosen because of its excellent safety profile (same negligible toxicity as with lower and higher dose levels) and pharmacokinetic findings. The latter showed steady state serum levels of 14.1±4 μM at dose level 1, 32.8±8.1 μM at dose level 2, and 31.6±7.8 μM at dose level 3. The rationale for selecting dose level 3 over dose level 2 was that perifosine at all dose levels was equally well tolerated by patients, and higher dosing was more likely assure therapeutic serum levels, given the wide interpatient variability observed in adult studies.3,4

Pharmacokinetic studies

Serum for perifosine levels was obtained on days 1, 8, 15 and 22 of cycle 1. At each time point, heparinized blood was collected into a plastic vacutainer to minimize adhesion of perifosine. Plasma was separated by centrifugation and stored in polypropylene cryovials at −80°C until assayed. Perifosine in plasma was measured by a validated reversed phase liquid chromatography/electrospray mass spectrometry method.15

Assessment of disease status

HR-NB patients underwent comprehensive extent-of-disease evaluations every 8 weeks x12 months from enrollment, then selective scans ± bone marrow (BM) studies every 8 weeks while continuing to take perifosine. Radiographic studies included computed tomography, 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan (with Curie scores obtained as described16), and positron emission tomography. BM studies comprised standard histochemical studies of aspirates/smears and biopsies from bilateral posterior and anterior iliac crests (i.e., four sites, which contrast with the two sites in international guidelines17). Disease status was defined by the International NB Response Criteria,17 modified to incorporate 123I-MIBG findings: complete remission (CR): no evidence of NB in soft tissue, bones, or BM; very good partial remission: primary mass reduced by ≥90%, and no evidence of distant disease in soft tissue, bones, or BM, including negative 123I-MIBG scan; partial response (PR): >50% decrease in measurable soft tissue disease and the number of metastatic skeletal lesions in 123I-MIBG scan, and ≤1 positive BM site; mixed response (MR): >50% decrease of any lesion with <50% decrease in any other, and 123I-MIBG scan improved by <50% decrease in number of (+) sites; no response: <50% decrease but <25% increase in any existing lesion, unchanged 123I-MIBG findings; and PD: new lesion or >25% increase in an existing lesion.

Statistical analysis

Efficacy was measured by response rate where response was either disease regression (MR, PR, or CR) or documentation of no PD at 6 months. A response rate of 10% was considered undesirable and 25% promising. The study’s goal was to assess whether there is an indication that the response rate is promising so that a larger phase II or III study could be initiated. Thus we used type II error rate of 10% for the study design.

In order to achieve our objective we obtained the minimum number of subjects necessary such that the probability of observing 0 or 1 responses was 10% if the true response rate was 25%. This number was 14 and decision rule was launch a phase II or III study if at least two patients responded. The probability of launching a phase II or III study was 41.5%, 80.2% and 89.9%, respectively, when the true response rates were 10%, 20% and 25%.

The follow-up study was designed to have 10% type I error rate and 90% power so that the combined type I error rate will be less than 5% and power over 80%.

If three or more of the 14 NB patients experienced dose-limiting toxicity at dose level 3, the MTD would be revisited. The probability of revisiting the MTD was 16%, 55% or 84% for a true toxicity rate of 10%, 20%, or 30%, respectively.

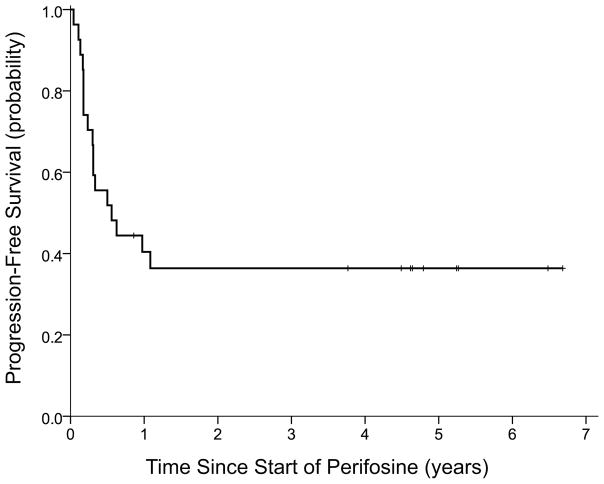

Progression-free survival (PFS) from the first dose of perifosine through PD, death, or last day of follow-up was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method.

RESULTS

Study patients

A total of 27 HR-NB patients received perifosine monotherapy according to protocol. This cohort included 22 patients who met all eligibility criteria: eight in the dose-escalation arm and 14 in the expansion arm. In addition, the absence of hematologic, hepatic, and unexpected toxicities prompted single patient usage of perifosine (as per the expansion arm) in five patients who were ineligible for formal enrollment because of age >21 years, grade 3–4 abnormalities of liver function enzymes, and/or thrombocytopenia. Twenty-six patients had stage 4 NB initially diagnosed at >3 years of age, and one patient was 4 months old with a localized NB but had two subsequent metastatic osteomedullary relapses. MYCN amplification was present in 1/24 patients. No tumor had an ALK mutation (21 tested).

When started on perifosine, the 27 patients (15 male, 12 female) were 4.7–33.5 (median 10.1) years old and 2.5–8.0 (median 4.5) years from diagnosis. Three patients were treated for primary refractory disease (i.e., persistence of NB but no PD) and 24 were treated for NB resistant to salvage therapy after 1–5 (median 2) prior relapses. Sites of disease at study entry were soft tissue alone (one patient), soft tissue plus osteomedullary by 123I-MIBG scan (n=2), and osteomedullary by 123I-MIBG scan alone (n=17) or by 123I-MIBG scan plus BM histology (ganglioneuroma, n=5; primitive NB, n=2). Prior therapy included HR-NB induction chemotherapy and 2nd-line chemotherapy (all patients); anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody (n=24); myeloablative therapy with stem-cell transplantation (n=18); and targeted systemic radiotherapy with 131I-MIBG (n=10) or 131I-labeled anti-GD2 antibody 3F8 (n=3).

Outcome

A total of nine patients have remained progression-free through 43+ to 74+ (median 54+) months from study entry (Table 1), including one patient (#5) who received additional investigational therapy after being on this trial for 11 months. Objective responses included one CR (patient #6) and two PRs (patients #2 and #4); the other six long-term survivors had persistence of abnormal osteomedullary 123I-MIBG uptake but never developed PD. All nine took perifosine (six at dose level 3, one each at dose level 1, 2, and 4; Table 1) for prolonged periods (11-to-62 months, median 38). Four of these patients (#2, #3, #4, #5) had ganglioneuroma in BM at study enrollment; these mature cells disappeared with perifosine monotherapy. None of these nine patients had MYCN-amplified disease, while 8/8 tested had wild type ALK (not tested in patient #6).

Table 1.

Clinical profiles of long-term progression-free survivors treated with perifosine monotherapy

| Patient # | No. of prior relapsesb | Age (yrs)at Dx | Age (yrs) at entry | Dose level | Yrs from Dx | ----------------- Prior therapya ------------------ | Curie score | Steady state serum level | Yrs from start of perifosine | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted radiotherapy | SCT | MAb | |||||||||

| 1. | none | 3.1 | 7.9 | 3 | 4.7 | … | tandem | 3F8 | 2 | 15.52 μM | 4.5 |

| 2. | none | 3.3 | 7.2 | 3 | 3.9 | 131I-MIBG, 131I-3F8 | … | 3F8 | 8 | 23.91 μM | 4.4 |

| 3. | none | 4.8 | 7.9 | 4 | 3.1 | 131I-3F8 | … | 3F8 | 6 | 19.55 μM | 4.7 |

| 4. | one | 4.1 | 12.1 | 2 | 7.9 | 131I-MIBG | single | 3F8 | 8 | 36.65 μM | 6.4 |

| 5. | one | 5.6 | 10.2 | 1 | 4.5 | 131I-MIBG, 31I-3F8 | single | 3F8 | 10 | 17.87 μM | 6.5c |

| 6. | one | 7.2 | 10.1 | 3 | 2.9 | … | single | … | 8 | 24.62 μM | 4.5 |

| 7. | one | 11.8 | 17.4 | 3 | 5.5 | … | single | 3F8 | 8 | 19.75 μM | 3.7 |

| 8. | two | 0.3 | 4.7 | 3 | 4.4 | 131I-MIBG (x2) | single | … | 3 | … | 5.1 |

| 9. | two | 3.1 | 7.9 | 3 | 4.7 | … | single | ch14.18, 3F8 | 1 | … | 5.1 |

Abbreviations: Dx, diagnosis; MAb, anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody; SCT, stem-cell transplantation; yrs, years

Included dose-intensive induction and 2nd-line chemotherapy in all patients.

At enrollment, patients #1–3 had primary refractory disease, i.e., persistent disease but no prior history of progressive disease or relapse, and patients #4–9 had residual disease despite salvage therapy for prior relapse.

Received additional investigative therapy.

Among the other 18 patients, three remained on study (dose level 3) for >6 months before an event: one with a history of 1 prior relapse died progression-free at 9 months from viral pneumonia (unrelated to protocol therapy); one with a history of 3 prior relapses had PD at 11.5 months; and the sole study patient with MYCN-amplified NB (1 prior relapse) had focal PD (cervical node) at 12.5 months (perifosine serum level 24.88 μM). Twelve patients had early PD, i.e., 0.5–3.5 months from enrollment, and three had PD documented 5.5–7.5 months from enrollment. PFS was 36% (SE±9%) at 36 months from day 1 of perifosine (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival of all 27 patients from start of perifosine monotherapy.

Pharmacokinetics

The average steady state serum level of perifosine was calculated for 21 patients and ranged from 12.21 μM-to-36.65 μM (median 19.75 μM).

Toxicity

Treatment was well tolerated by all 27 patients, with no dose-limiting toxicity, no problems in administration of perifosine, no evidence of cumulative toxicity over months-to-years, and no patient coming off study because of toxicity or side effects. Two patients had transient grade 3 hepatotoxicity. This absence of toxicity was noteworthy given each study patient’s extensive prior multi-modality therapy. The only other grade 3–4 toxicities – all unrelated to perifosine, all self-limited, and all attributable to prior therapy or intercurrent events such as viral syndromes – were hematologic, including neutropenia, lymphopenia, or thrombocytopenia.

DISCUSSION

In this first reported study of the AKT inhibitor perifosine as monotherapy in children, the treatment was well tolerated, similar to adult studies3, 4 with no significant toxicity despite the ubiquity of AKT pathways in normal tissues. The clinical and pharmacokinetic findings confirm a safe dosage to achieve therapeutic serum levels of perifosine in children. Indeed, the ease of administration and the absence of hematologic or non-hematologic toxicity in the study patients – all of whom had received extensive prior therapy – help explain why families of patients without PD were eager to continue perifosine monotherapy for years.

Nine of the 27 HR-NB patients became long-term progression-free survivors (Table 1). This gratifying result was unexpected given that patients with primary refractory HR-NB have a poor prognosis and relapse of HR-NB after contemporary multi-modality therapy is deemed to be “invariably fatal.”18 Yet caution is warranted when considering whether to attribute the good outcomes to perifosine. One of these patients had a CR, with normalization of MIBG scan, but delayed effects of prior therapy cannot be discounted. The other eight patients may have had relatively quiescent malignant disease when enrolled since they had stable MIBG findings for prolonged periods before, during, and after perifosine monotherapy; their PET scans did not show abnormal uptake unequivocably indicative of metabolically-active neoplastic deposits; and BM disease at study entry was limited to ganglioneuroma (4 patients).

Conclusions regarding anti-NB activity of perifosine in the clinical setting cannot be applied to MYCN-amplified disease since only one study patient had this adverse prognostic marker. Nevertheless, the prolonged PFS (12.5 months), with only a focal relapse, of this patient is notable given the often rapid PD and early demise with resistant MYCN-amplified NB.19 This all-too-common clinical course likely accounts for the paucity of MYCN-amplified patients in our study. Pre-clinical studies suggest that inhibition of the AKT pathway, including with perifosine, is active against MYCN-amplified NB.8,12,14,20

Biological, preclinical, and clinical findings suggest that perifosine holds promise as an agent that can help improve the prognosis of HR-NB patients without worsening the long-term noxious sequelae associated with aggressive multi-modality anti-NB therapy. Clinical studies of NB patients strongly support targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway. Thus, this pathway’s activation correlated with poor outcome and well-established markers of HR-NB including MYCN amplification, chromosome 1p aberrations, unfavorable histology, advanced disease stage, and older age,13 as well as CD133 expression, a more recently identified adverse prognostic marker.20 Conversely, activation was largely absent in low-risk NBs detected by mass screening.21

A variety of RTKs influence NB pathogenesis and malignant behavior via the PI3K/AKT pathway,5–7 including receptors for brain-derived neurotropic factor,8 epidermal growth factor,9 insulin-like growth factor,10 and vascular endothelial growth factor.11 Hence, the anti-AKT activity of perifosine can affect NB without regard to which specific RTKs are involved in a given tumor.5–7 Furthermore, perifosine, unlike other oncologic agents that target DNA or RNA, primarily acts at the cell surface5 - and activation of PI3K results in translocation of AKT to the plasma membrane. Finally, inhibiting the AKT pathway with perifosine22 or other agents20,23 appears to enhance the antitumor effect of chemotherapy, biological agents, and radiotherapy.5–8 This finding plus its lack of toxicity make perifosine an attractive candidate for coadministration with other treatment modalities.

In our expansion cohort, the dosing of perifosine was arrived at in the phase I component of this trial where steady state serum levels of ~32 μM were documented. Levels were lower in the expansion cohort but approximated those in adults.4 These serum levels matched the perifosine concentrations that showed anti-NB activity in laboratory studies.8,14 The latter, which included animal models, involved NB cell lines containing biological features seen with aggressive NB including MYCN amplification, chromosome 1p deletions, and mutations of tumor protein p53 which is associated with chemoresistance. In those preclinical studies,8,14 activity was also noted against cell lines with aberrations of ALK that confer resistance to ALK inhibitors which are a new anti-NB treatment attracting much interest.18 ALK mutations were absent in the 21 study patients tested.

In summary, perifosine monotherapy was confirmed to be a safe and well-tolerated treatment in children with HR-NB despite the role of AKT in normal tissues. This clinical experience and a wide range of preclinical studies suggest that perifosine could be readily combined with other oncologic treatments to achieve additive or synergistic antitumor effects. It might also be considered as treatment after completion of standard therapy for HR-NB, though perhaps only for MYCN-non-amplified disease, given that to date only preclinical data support perifosine for MYCN-amplified disease.8,12,14,20 The progression-free survival off all therapy of 9/27 study patients with very long follow-up (Table 1) adds to accumulating evidence that refractory or relapsed HR-NB can potentially be cured.24, 25

NOVELTY AND IMPACT.

Various receptor tyrosine kinases mediate clinical features of neuroblastoma via the PI3K/AKT pathway. In preclinical studies, the AKT inhibitor perifosine shows excellent anti-neuroblastoma activity. 9/27 patients treated for resistant neuroblastoma remain progression-free >43 months, adding to evidence elsewhere that refractory/relapsed neuroblastoma is curable. Serum levels matched perifosine concentrations that are cytotoxic in vitro. Toxicity was negligible, alleviating concern about suppression of the PI3K/AKT pathway, especially in heavily prior-treated children, and supporting use with other therapies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jill M. Kolesar, Pharm.D., for performing the pharmacokinetic studies.

FUNDING

This work was supported in part by grants from the Gerber Foundation, Fremont, MI; the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748; the Robert Steel Foundation, New York, NY; and Katie’s Find A Cure Fund, New York, NY.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BM

bone marrow

- CR

complete remission

- HR-NB

high-risk neuroblastoma

- MIBG

metaiodobenzylguanidine

- MR

mixed response

- MSKCC

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

- MTD

maximum tolerated dosage

- PD

progressive disease

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PR

partial response

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nitulescu GM, Margina D, Juzenas P, Peng Q, Olaru OT, Saloustros E, Fenga C, Spandidos D, Libra M, Tsatsakis AM. Akt inhibitors in cancer treatment: The long journey from drug discovery to clinical use (Review) International journal of oncology. 2016;48:869–85. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Courtney KD, Corcoran RB, Engelman JA. The PI3K pathway as drug target in human cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:1075–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Ummersen L, Binger K, Volkman J, Marnocha R, Tutsch K, Kolesar J, Arzoomanian R, Alberti D, Wilding G. A phase I trial of perifosine (NSC 639966) on a loading dose/maintenance dose schedule in patients with advanced cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2004;10:7450–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Figg WD, Monga M, Headlee D, Shah A, Chau CH, Peer C, Messman R, Elsayed YA, Murgo AJ, Melillo G, Ryan QC, Kalnitskiy M, et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of oral perifosine with different loading schedules in patients with refractory neoplasms. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2014;74:955–67. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2569-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun W, Modak S. Emerging treatment options for the treatment of neuroblastoma: potential role of perifosine. OncoTargets and therapy. 2012;5:21–9. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S14578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fulda S. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway as therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Current cancer drug targets. 2009;9:729–37. doi: 10.2174/156800909789271521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brodeur GM. Getting into the AKT. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102:747–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Z, Thiele CJ. Targeting Akt to increase the sensitivity of neuroblastoma to chemotherapy: lessons learned from the brain-derived neurotrophic factor/TrkB signal transduction pathway. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets. 2007;11:1611–21. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.12.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho R, Minturn JE, Hishiki T, Zhao H, Wang Q, Cnaan A, Maris J, Evans AE, Brodeur GM. Proliferation of human neuroblastomas mediated by the epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer research. 2005;65:9868–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerreiro AS, Boller D, Shalaby T, Grotzer MA, Arcaro A. Protein kinase B modulates the sensitivity of human neuroblastoma cells to insulin-like growth factor receptor inhibition. International journal of cancer. 2006;119:2527–38. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ngan ES, Sit FY, Lee K, Miao X, Yuan Z, Wang W, Nicholls JM, Wong KK, Garcia-Barcelo M, Lui VC, Tam PK. Implications of endocrine gland-derived vascular endothelial growth factor/prokineticin-1 signaling in human neuroblastoma progression. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2007;13:868–75. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnsen JI, Segerstrom L, Orrego A, Elfman L, Henriksson M, Kagedal B, Eksborg S, Sveinbjornsson B, Kogner P. Inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin downregulate MYCN protein expression and inhibit neuroblastoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 2008;27:2910–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opel D, Poremba C, Simon T, Debatin KM, Fulda S. Activation of Akt predicts poor outcome in neuroblastoma. Cancer research. 2007;67:735–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Z, Tan F, Liewehr DJ, Steinberg SM, Thiele CJ. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of neuroblastoma tumor cell growth by AKT inhibitor perifosine. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102:758–70. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woo EW, Messmann R, Sausville EA, Figg WD. Quantitative determination of perifosine, a novel alkylphosphocholine anticancer agent, in human plasma by reversed-phase liquid chromatography-electrospray mass spectrometry. Journal of chromatography B, Biomedical sciences and applications. 2001;759:247–57. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(01)00231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ady N, Zucker JM, Asselain B, Edeline V, Bonnin F, Michon J, Gongora R, Manil L. A new 123I-MIBG whole body scan scoring method--application to the prediction of the response of metastases to induction chemotherapy in stage IV neuroblastoma. European journal of cancer. 1995;31A:256–61. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)00509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brodeur GM, Pritchard J, Berthold F, Carlsen NL, Castel V, Castelberry RP, De Bernardi B, Evans AE, Favrot M, Hedborg F, et al. Revisions of the international criteria for neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging, and response to treatment. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11:1466–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.8.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole KA, Maris JM. New strategies in refractory and recurrent neuroblastoma: translational opportunities to impact patient outcome. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012;18:2423–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kushner BH, Modak S, Kramer K, LaQuaglia MP, Yataghene K, Basu EM, Roberts SS, Cheung N-KV. Striking dichotomy in outcome of MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma in the contemporary era. Cancer. 2014;120:2050–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sartelet H, Imbroglio T, Nyalendo C, Haddad E, Annabi B, Duval M, Fetni R, Victor K, Alexendrov L, Sinnett D, Fabre M, Vassal G. CD133 expression is associated with poor outcome in neuroblastoma via chemoresistance mediated by the AKT pathway. Histopathology. 2012;60:1144–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sartelet H, Ohta S, Barrette S, Rougemont AL, Brevet M, Regairaz M, Harvey I, Bernard C, Fabre M, Gaboury L, Oligny LL, Bosq J, et al. High level of apoptosis and low AKT activation in mass screening as opposed to standard neuroblastoma. Histopathology. 2010;56:607–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z, Oh DY, Nakamura K, Thiele CJ. Perifosine-induced inhibition of Akt attenuates brain-derived neurotrophic factor/TrkB-induced chemoresistance in neuroblastoma in vivo. Cancer. 2011;117:5412–22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bender A, Opel D, Naumann I, Kappler R, Friedman L, von Schweinitz D, Debatin KM, Fulda S. PI3K inhibitors prime neuroblastoma cells for chemotherapy by shifting the balance towards pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins and enhanced mitochondrial apoptosis. Oncogene. 2011;30:494–503. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung NK, Cheung IY, Kramer K, Modak S, Kuk D, Pandit-Taskar N, Chamberlain E, Ostrovnaya I, Kushner BH. Key role for myeloid cells: phase II results of anti-G(D2) antibody 3F8 plus granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for chemoresistant osteomedullary neuroblastoma. International journal of cancer. 2014;135:2199–205. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kushner BH, Ostrovnaya I, Cheung IY, Kuk D, Kramer K, Modak S, Yataghene K, Cheung NK. Prolonged progression-free survival after consolidating second or later remissions of neuroblastoma with Anti-G immunotherapy and isotretinoin: a prospective Phase II study. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e1016704. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1016704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]