Abstract

The Behavior Analysis Certification Board continues to increase the standards for supervision of trainees, which is needed in order for the field to continually improve. However, this presents a challenge for organizations to meet the needs of both their clients and their supervisees based on these increasing standards. Throughout the ages, experts in all trades have passed along their knowledge and skill through apprenticeship opportunities. An apprenticeship supervision model is described that allows Board Certified Behavior Analysts to supervise future behavior analysts by mentoring, educating, and training supervisees on the science of human behavior in a format that is mutually beneficial. This innovative supervision model is discussed as it applies to an applied behavior analysis human service organization with the goal of creating a system that results in high-quality supervision in a cost-effective manner while providing maximal learning for the supervisee. The organization’s previous supervision difficulties are described prior to implementing the apprenticeship supervision model, and the benefits of developing and using the apprenticeship supervision model are outlined.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40617-016-0136-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Applied behavior analysis, Behavior Analysis Certification Board, Board Certified Behavior Analyst, Autism, Apprenticeship supervision model

The prevalence of autism continues to rise, with estimates as high as one in 38 individuals with a diagnosis of autism worldwide (Reagon, 2016). These astonishing rates have resulted in a continual increasing need for behavior analyst practitioners specifically trained to work with individuals on the autism spectrum. Although the number of Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA®) certificants across the world has substantially increased in recent years, with 1817 new BCBAs in 2012 and a rise to 3185 new BCBAs in 2014 (a 75 % increase in 2 years), there continues to be a need for additional BCBAs to support the growing autism population as well as those with pediatric behavior disorders, traumatic brain injury, and mental health disorders. These are all areas which have an increasing need for behavior analytic services (Courtney, McKee, Woolf, Ross, & Zarcone, 2016). In 2015, it was estimated that 75,000 BCBAs were needed in order to support the growing need for behavior analytic services. However, there were a total of 19,795 BCBA certificants (Carr, 2016). This is a deficit of over 55,000 BCBAs. Because of this deficit, now more than ever, it is extremely important to identify quality training systems that produce exceptional BCBA practitioners.

New professionals seeking board certification as a behavior analyst are needed to work with the underserved autism and developmental disability population. Experience with autism was listed as the most frequently cited skill demanded by employers seeking behavior analysts in 2014. The need for autism experience, as indicated in job postings, increased from 43 % in 2012 to 53 % in 2014. Additionally, experience with autism was cited as the most commonly requested skill of behavior analysts in the top three major industries of healthcare, education, and social assistance (Burning Glass Technologies, 2015). As a result, it is essential for the behavior-analytic organization to identify effective supervision practices for these individuals, because the development of skilled BCBAs with experience with autism will be directly beneficial to the organization and to the community at large in order to provide future behavior-analytic services.

Recently, Sellers, Valentine, and LeBlanc (2016) and Turner, Fischer, and Luiselli (2016) recommended many beneficial supervisor practice guidelines when providing supervision within the field of ABA. These guidelines are recommended in an attempt to streamline the supervision practices of BCBAs working in human service agencies, as it is typically uncommon for a BCBA to receive specific training regarding how to provide effective supervision that results in the competency of a new BCBA. These references focus on identifying key behaviors the supervisor should engage in to produce quality learning opportunities for a supervisee. This article assumes that the supervisor has acquired the skill set described by Sellers et al. (2016) and Turner et al. (2016). This article adds to the knowledge base of practicing behavior analysts by identifying a workable system of supervision and demonstrating how an organization can utilize its supervisors and supervisees optimally to produce quality supervision. Sellers et al. recommend five practice guidelines which include establishing the relationship, establishing the content of supervision and how competence will be evaluated, evaluating the effects of supervision, incorporating ethics, and continuing the professional relationship after certification. Turner et al. provide suggestions for how to successfully implement competency-based supervision to include how to set the occasion for collaborative supervision, how to conduct a baseline assessment of trainee skills, how to teach and promote skills, how to develop problem solving and decision making, how to deliver performance feedback, and how to evaluate the outcomes of supervision. The purpose of this article is to present an apprenticeship model of supervision for which an organization can adopt that will allow its BCBAs to successfully supervise future behavior analysts. Within this apprenticeship supervision model, a supervisor is able to mentor, educate, and train supervisee employees on the application of behavior analysis while the supervisee acts as the novice who is learning the skill set required to provide effective behavior-analytic services by her supervisor, the experienced BCBA. The BCBA supervisor instructs, models, and provides feedback to the supervisee, creating continuous learning opportunities in order to shape a repertoire of effective clinical oversight. The apprenticeship supervision model will be described as a process used to improve a behavior-analytic organization that was experiencing an increase in need for effective supervision practices from employees seeking board certification. The goal was to create an innovative model that meets the supervision standards in a cost-effective manner, while still providing maximal learning for the supervisee.

The leadership of the behavior-analytic organization should support shaping the repertoires of future behavior analysts whom it employs, because this falls in line with the purpose of the Behavior Analysis Certification Board (BACB®) certification effort, as described by Shook and Favell. The authors stated that “This BACB certification effort was intended to (a) provide consumers with a basic credential that identified a qualified behavior analysis practitioner, (b) increase the quality of behavior analysis services available to the consumer, and (c) increase the amount of behavior analysis services available” (Shook & Favell, 2008, p. 44). For this reason, the leadership team at the behavior-analytic organization is likely enthusiastic about the possibility of hiring staff members who have an interest in working toward board certification. However, the responsibility of providing the fieldwork supervision to supervisees can be cumbersome, as it requires time, energy, and creativity on the part of the BCBA supervisor, which could result in a shift of focus away from the progress and continued development of their clients with autism. Despite the effort associated with good supervision, the leadership team at a behavior-analytic organization should be committed to developing a successful and mutually beneficial supervision model in line with Shook, Johnston, and Mellinchamp’s (2004) notion that every certificant should positively represent behavior analysis due to the fact that each new interaction is an opportunity to impact and support the field of behavior analysis.

The Behavior-Analytic Professional Organization

The behavior-analytic professional organization that is described is a non-profit organization in the Midwest which has provided applied behavior analysis (ABA) services to individuals on the autism spectrum since 2002. The organization provides services in a state with an autism mandate that has been in existence since 2001. At the writing of this article, “44 states have passed insurance mandates that require most commercial health plans to pay for the diagnosis and treatment of children with autism” (“Study suggests insurance mandates,” 2016). Through the use of the state autism mandate, the organization provides services to approximately 140 individuals on the autism spectrum, ranging in age from 2 to 25 years, across seven different center or home-based programs within a single state. The organization uses 12 funding sources to bill for ABA services, which includes 10 insurance companies, Medicaid, and school corporations.

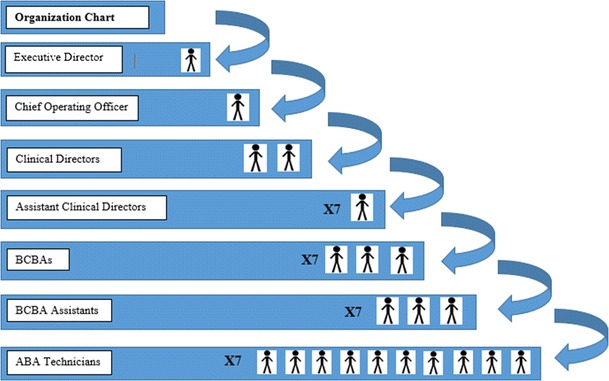

The organization employs approximately 230 individuals, of which 115 of 130 direct-line technicians are Registered Behavior Technicians (RBT™, a paraprofessional category) through the BACB, and 30 are certified as either a BCBA-D™ (i.e., have a doctoral degree), a BCBA, or a BCaBA (i.e., Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analysts®). The 30 certificants encompass the clinical structure of the organization, which consists of a single BCBA-certified chief operations officer who supervises and works closely with two BCBA-certified clinical directors. The two clinical directors oversee seven assistant clinical directors, who are the lead BCBAs overseeing their designated programs. Each assistant clinical director oversees approximately three BCBAs. Those BCBAs are each assigned to the oversight and development of the programming of a caseload of individuals on the autism spectrum (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Organization chart hierarchy of certifiants, BCBA apprentices, and technicians. The organization includes 7 Assistant Clinical Director’s with an accompanying number of BCBA’s, BCBA apprentices, and ABA technicians

History Within the Organization of BCBA Supervision and Supervision Difficulties

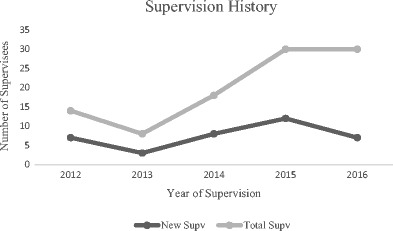

Since 2012, the behavior-analytic professional organization has provided BCBA supervision to 37 employees. The number of new supervisees in 2012 was seven, the total number of supervisees in 2013 was five (including three new supervisees), the total number of supervisees in 2014 was 10 (including eight new supervisees), the total number of supervisees in 2015 was 18 (including 12 new supervisees), and the projected total number of supervisees in 2016 is 23 (including seven new supervisees). These numbers show an increasing trend in the number of employees seeking supervision, which supports the need for a systematic and efficient supervision model (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Summary of the number of supervisees who received supervision from the organization from 2012 through the present

Of the 37 employees who have received BCBA supervision over the past 5 years, 23 continue to work toward board certification by accumulating supervision hours, and five have become board certified and are full-time employees of the organization. The remaining nine supervisees have either moved into non-clinical roles within the organization which do not require board certification, failed to pass the BCBA exam, and are preparing to retake the exam while continuing employment with the organization, or have moved on to other employment opportunities.

In an attempt to provide BCBA supervision to its employees, the organization has experienced difficulties that many other organizations may have experienced as well. These challenges have consisted of (a) inconsistency with the type of learning opportunities provided to the supervisee; (b) the amount of time and effort associated with supervision for the BCBA supervisor, which has pulled that supervisor away from her typical work responsibilities; (c) lack of opportunity for supervisees to accumulate indirect supervision hours; and (d) low number of supervisees advancing to BCBA positions within the organization.

Inconsistency of Learning Opportunities

Historically, some supervisors provided more or less academically related learning opportunities to their supervisees than others, likely based upon their own personal interest and motivation. This is in contrast to providing learning opportunities more focused on the nature of the applied setting as it relates to the progress of individuals being served. Although the acquisition and mastery of behavior-analytic principles and concepts is extremely important, the context in which that information is acquired is arguably more appropriate through an academic setting than through supervision in an applied setting. An example of inconsistency of learning opportunities in an applied setting is if one supervisor is particularly motivated for her supervisee to master the discrimination between radical and methodological behaviorism while another supervisor is particularly interested in having her supervisee master differences between the experimental analysis of behavior and the conceptual analysis of behavior. Acquiring an understanding of both is beneficial; however, the outcome is having two supervisees with varying degrees of emphasis on certain behavioral concepts. Additionally, although the mastery of these two different behavioral concepts are important, it is not necessary for a supervisee to have those particular discriminations mastered in order to succeed in providing services in an applied setting. Arguably, it is more beneficial for those concepts to be acquired in an academic setting through university coursework.

Supervisor Responsibilities

Providing high-quality, intensive learning opportunities regarding the concepts of behavior analysis requires a great deal of time and effort that a practicing BCBA will likely not have allotted within her work day. Most BCBA practitioners are focused, as their name implies, on practicing behavior-analytic skills rather than teaching others to implement those skills. Contrastingly, graduate instructors in a university setting are optimally equipped to provide supervisees with knowledge associated with the history of behavior analysis, the foundational principles of behavior analysis, and the scope of behavior-analytic principles across a variety of settings and populations through course lectures and discussions, assignments pertaining to specific learning objectives, and quizzes and exams to test for competency. An applied setting is more appropriate for supervision consisting of application of the concepts of behavior analysis, rather than initially learning the concepts themselves. An applied setting is optimally equipped to take what supervisees know about behavioral principles and teach them how to implement that knowledge in a meaningful way. Essentially, supervisees should receive training on behavior-analytic concepts in their coursework and receive training on practical and applied clinical skills in an applied setting, oftentimes as an employee. The notion of supervising in this fashion was supported by Shook et al. (2004) who indicated that the nuances of learning the science of behavior were better acquired as a student in an academic setting versus as an employee in a clinical setting.

There is an art to behavioral application that a supervisee can only learn from a master practitioner (Friman, 2015). The roles of the university setting and the applied field experience are complimentary, thus making it necessary for supervisors in the applied setting to spend very little time with supervisees on theories of behavior analysis and the vast majority of time on practice-related issues. For example, Friman (2015) notes that an experienced practitioner encompass the skill set required to gracefully begin a treatment session by greeting the client in a socially appropriate manner, which is a set of behaviors entirely necessary to succeed in the applied setting but that cannot be taught to mastery within the content of university coursework.

Lack of Opportunity for Supervisees to Accumulate Indirect Supervision Hours

Supervisees tend to hold full-time positions as direct implementers within the behavior-analytic organization. As of the writing of this article, 85 % of the organization’s employees in the direct implementer role conduct therapy with individuals on a full-time basis, approximately 40 h per week. The 15 % of full-time employees that do not conduct therapy on a full-time basis provide support to a BCBA for half of their day.

Historically within the organization, the way in which supervisees could accumulate supervision hours was not systematic. Some supervisees happened to hold one of these rare BCBA support positions that nicely allowed for both direct implementation and other supervision activities to occur. On the other hand, other supervisees held positions that required the implementation of full-time therapy, therefore not allowing for other supervision opportunities. This does not meet the criteria identified by the BACB in the Experience Standards, which state “direct implementation of behavior programs may not count for more than 50 % of the total accrued experience hours” (BACB, 2015, p. 3).

Low Number of Supervisees Advancing to BCBA Positions

Of 37 employees for whom the organization has provided supervision over the past 5 years, five are currently employed by the organization as BCBAs. Based on this information, it is projected that only 14 % of the supervisees the organization provides supervision to will transition into BCBA positions after their supervision is completed. Additionally, only 39 % of the supervisees within the organization held positions that would allow for comprehensive supervised independent fieldwork experiences consisting of both direct and indirect implementation. Clearly, the previous supervision model was not effective, as it would have been more beneficial for the organization and its clientele for a much larger percentage of supervisees to have received supervision and transitioned into BCBA roles.

Resolution of Difficulties

Because of the difficulties previously identified, the leadership of the organization determined that it was necessary to develop a new supervision model. One of the goals of the new BCBA supervision structure was to identify a system that would utilize typical oversight activities, while still meeting the BACB’s supervision requirements and standards. As a result, an apprenticeship model was developed and implemented.

The Organization’s Model for Meeting BACB Supervision Requirements

The BACB requires four areas of completion in order to become a BCBA:

Completion of a minimum of a graduate degree.

Completion of coursework.

Completion of experience, in compliance with experience standards.

Passing an examination (BACB, n.d.).

The completion of experience, in compliance with experience standards, is the only area that the organization provides as structured support for its supervisees. The other required components are responsibilities of the supervisee to complete independent of the organization, through their graduate university or through additional supplemental supports. The organization’s structure allows for the “supervised independent fieldwork” experience option for supervisees rather than the practicum or intensive practicum experience options. The supervised independent fieldwork option will be the option described throughout this article.

The Apprenticeship Model

The organization’s goal is to provide training and oversight to its supervisees so that those supervisees become competent in working with the autism population in center-based and home-based settings. Because an individual working toward becoming a BCBA will likely be exposed to a very comprehensive set of information regarding different populations and areas of work through their coursework, the organization seeks to train its supervisees to be an expert solely with individuals on the autism spectrum. In order to be successful as an expert in a particular area, a supervisee must receive training that is specialized. Under Section 1.02 of the Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2014), BCBAs must teach to that specificity.

For that reason, the organization uses an apprenticeship model, wherein its supervisees become experts with the autism population by shadowing and purposefully learning the BCBA role in autism-specific programming by applying behavior analytic principles to skill acceleration and behavior deceleration objectives. This supervision system has an emphasis on application of behavior principles and places less emphasis on the mastery of terminology; however, the supervisee is expected to speak behaviorally when interacting with other BCBAs.

The organization supports and encourages its supervisees to seek quality academic graduate training in a university setting rather than relying solely on learning the breadth of behavior analysis from an applied setting only. Supervisees have resources readily available to them which provide information regarding appropriate academic programs, such as the Behavior Analysis Accreditation Board (BAAB) of the Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI), which accredits programs “that encourage, support, and recognize exemplary training of behavior scientists and scientist-practitioners” (BAAB/ABAI, 2016, p. 4), as well as the BACB, which approves course sequences that have been identified to be adequate in disseminating information about the core behavior-analytic practices (BACB, n.d.). An ideal model for a supervisee is to work toward becoming a scientist-practitioner, for which the scientist repertoire is developed within the university to “clearly emphasize ABA’s grounding within a technological, analytic, and conceptually systematic framework in which ‘knowledge creation’ is defined by empirical research” (Dixon, Reed, Smith, Belisle, & Jackson, 2015, p. 8, referring to Baer, Wolfe, & Risley, 1968), whereas the practitioner repertoire is developed within the practicum setting. Although the scientist and the practitioner repertoires are established in two different settings, the organization’s clinical team encourages supervisees to practice scientifically so that the two repertoires are blended in order to most effectively evaluate assessment and treatment procedures based on the analysis of data.

This apprenticeship supervision model aims to shape supervisees into becoming exceptional BCBA autism practitioners. Critchfield (2015) indicated that a successful practitioner is identified by the success of her clients. Therefore, in order to allow supervisees to become exceptional practitioners who consistently work toward success and progress with their clients, the organization’s training is designed to be even more specialized by assigning the supervisees to one of three age ranges: early learner (diagnosis through age six), adolescent learner (age seven through age 12), or teenage/adult learner (age 13 through age 25 and older). Supervisees have the opportunity to learn the details of providing ABA services to this specific age group through a variety of “performance based competencies.” These performance-based competencies consist of navigating the insurance funding process, mastering treatment plan writing, learning how to transition clients from home or center-based settings to school or employment settings as appropriate, learning to develop goals and write treatment plans for that age range under the direction of a BCBA, learning to identify problems in current programming and systematically looking for answers, and learning to train technicians to improve in their therapy implementation skills. On average, a supervisee typically spends approximately 15 h per week face-to-face with clients, 20 h per week engaged with indirect activities such as writing goals and treatment plans, and 5 h per week training technicians and providing feedback on ABA therapy implementation. Contrastingly, a supervisor will spend approximately 30 h per week face-to-face with clients in order to provide the appropriate clinical support required for a caseload of approximately 7–8 clients. The supervisor will spend the ten remaining hours of her week engaged in a combination of indirect tasks (similar to those mentioned for the supervisee) and training of technicians. A supervisee and her supervisor will typically overlap for approximately 5 h per week on any combination of the aforementioned tasks, which is time spent for the supervisor to train the supervisee as her apprentice.

BCBA Apprentice

Within the framework of this apprenticeship supervision model, the organization’s leadership team developed a highly competitive position specifically for the development of supervisees, known as a BCBA Apprentice (and different from a BCaBA). The minimum requirements to qualify for this role are enrollment in graduate-level applied behavior analysis courses. Preferred experiences include the completion of 750 direct hours of ABA therapy implementation overseen by a BCBA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of comparison between supervision of direct implementation responsibilities and supervision of BCBA Apprentice responsibilities

| Direct implementation | BCBA Apprentice |

|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 2 |

| First 750 h of supervision | Second 750 h of supervision |

| Unlimited number of supervisees | A limited number of competitive positions |

| Direct implementation of ABA therapy with clients | Assisting a BCBA with client and technician oversight |

| Receive monthly feedback | Receive monthly feedback |

The job responsibilities of a BCBA Apprentice consist of supervision activities in accordance with BACB guidelines such as designing behavioral programs, naturalistic observation, staff and caregiver training, researching the literature related to an individual’s program, and conducting acquisition and deceleration assessments (see Appendix A for the BCBA Apprentice job description). Through this supervision, the supervisor shapes behavioral case conceptualization, problem-solving, and decision-making repertoires for the supervisee while also modeling technical, professional, and ethical behavior. Delivery of performance feedback is conducted monthly in a systematic fashion.

The organization has a limited number of BCBA Apprentice positions available. This number is dependent on the total number of BCBAs within the organization, where one BCBA Apprentice is designated to assist every BCBA within the organization. The BCBA Apprentice position is non-billable; therefore, the organization is not compensated for the time the individuals in this position spend with their clients, which is quite costly. However, the development of the BCBA Apprentice position is advantageous because it not only allows for exemplary training opportunities for the future BCBA, but also allows the supervising BCBA to focus more on the direct, face-to-face supervision responsibilities of additional clients. These face-to-face responsibilities include observing treatment implementation by an ABA technician and potentially making recommendations regarding program revision, monitoring treatment integrity, and training ABA technicians and/or client caregivers to implement treatment programs (BACB, 2014).

Many funding sources are no longer allowing BCBAs to bill for work done indirectly with each client on their cases, for example, writing treatment plans, writing assessments, developing skill acquisition programs, and developing behavior reduction interventions. Shifting these indirect clinical responsibilities to the BCBA Apprentice, with the BCBA’s supervision and guidance, allows for making the BCBA’s caseload larger. By the standards of the organization, without a BCBA Apprentice, a BCBA could reasonably provide clinical oversight to approximately five clients, receiving comprehensive treatment, which equated to 20 h of direct clinical oversight and 20 h of indirect clinical oversight per week. With the addition of a BCBA Apprentice, a BCBA can provide clinical oversight to seven to eight clients, which is the equivalent to approximately 30 h of direct clinical oversight per week. Although each BCBA is responsible for ten additional hours of direct supervision per week with the apprenticeship model, the quality of services provided to the clients remains high due to the addition of an apprentice who is well-educated in behavior analysis and who is also responsible for client progress and successful outcomes. This model is financially beneficial to the organization because it requires hiring fewer highly compensated BCBAs to perform tasks that can be completed by others, while simultaneously maintaining high-quality services for each client because the BCBA can still oversee the tasks that are completed. The addition of two to three additional clients on each BCBA’s caseload results in a financial benefit to the organization of $475,000 to $500,000 annually. The model is similar to a doctor’s office wherein a medical assistant checks patients in, takes a patient’s blood pressure, weight, and medical history prior to the doctor’s visit. A BCBA Apprentice is eligible to remain in the position through the duration of her supervision. The supervisee can remain in the position for 2 years, or until she attempts to pass the BCBA exam twice.

A challenge associated with this model is that typically there are not an equivalent number of employees seeking supervision as there are BCBAs within the organization. This imbalance can cause problems, both when the number of supervisees exceeds the number of BCBAs, and when the number of supervisees is less than the number of BCBAs. If there are fewer supervisees interested in receiving indirect supervision hours than there are BCBA Apprentice positions available, then instead of assigning a BCBA Apprentice to the BCBA, a Temporary Assistant would be assigned to assist the BCBA instead. The difference between a BCBA Apprentice and a Temporary Apprentice is that a BCBA Apprentice is working toward becoming a BCBA and a Temporary Apprentice is not working toward becoming a BCBA (see Appendix B for a full Temporary Apprentice job description). If an equally qualified candidate becomes available who is pursuing board certification, then the Temporary Assistant will be asked to step down and fulfill full-time therapy duties.

If there are more supervisees interested in receiving indirect supervision hours than there are BCBA Apprentice positions available, then that supervisee can accrue up to 750 direct supervision hours, 50 % of the total number of supervision hours required (per BACB standards), by implementing ABA therapy. If the supervisee has already accrued 750 direct implementation supervision hours, then the supervisee must wait for a BCBA Apprentice position to become available in order to begin accumulating indirect supervision hours. This can become a problem for the organization because some staff in need of supervision may choose not to wait for an open position and instead opt to leave the organization. At this point within the supervision process, supervisees are free to resign from their position within the organization at no penalty if they wish to do so. However, there are some safeguards outlined in the organization’s supervision agreement to prevent supervisees from leaving the organization once they have obtained all of their supervised hours. The precautions outlined in the agreement state that “If the supervisee does not remain employed by the organization for one additional year following completion of all supervised experience hours, then the supervisee must promptly reimburse the organization for each hour they were directly supervised by a BCBA at a rate of $75.00 per hour.” As of the writing of this article, this has not been an issue.

Preparing for Supervision

Prior to beginning supervised independent fieldwork, the supervisee and the supervisor must sign and agree to the supervision contract designed by the organization under legal representation (see Appendix C for the organization’s supervision contract). Additional criteria required by the supervisee to begin supervision include the following:

Providing verification of current enrollment in behavior-analytic coursework.

Becoming credentialed as an RBT.

Providing verification of the completion of the BACB experience standard training module.

Supervised Independent Fieldwork Hours

The organization commits to providing supervision for a minimum of 15 fieldwork hours per week, while the BACB allows for up to 30 h of supervised fieldwork per week. The organization sets the expectation at 15 h per week because this results in one and a half supervision hours every 2 weeks for the supervising BCBA, which is an amount that fits well within the clinical organizational model of oversight and supervision of staff. The supervisory period identified by the BACB is 2 weeks. As a result, the supervisee accumulates a total of 30 supervision hours during that 2-week period (15 h in week 1 and 15 h in week 2). The BACB also identifies that a supervisor must directly supervise 5 % of accumulated fieldwork hours; therefore, the total supervision hours required in a 2-week period for a supervisee who has accumulated 30 h is one and a half hours (which is 5 % of 30 h) or 0.75 h every week (5 % of 15 h).

Independent Fieldwork Experience Hours

The BACB experience standards require 1500 h of supervised independent field work in behavior analysis. For a full-time employee of the organization, this translates to approximately 2 years of supervision. In order to obtain a broad set of experiences, the organization divides a supervisee’s 1500 h into three components.

Year 1: Direct Implementation

The BACB has identified that a supervisee can accumulate half of their supervision hours through direct therapy implementation. As a result, within the organization’s model, supervisees must have a minimum of 750 h of direct implementation as a technician, rotating through working with a variety of clients every couple of months, in order to ensure that a robust experience is achieved.

The organization is able to provide direct supervision to an unlimited number of technicians due to the organization’s structure of clinical oversight. Supervisors are already naturally observing the implementation of therapy through their clinical supervision responsibilities; therefore, they are also able to provide feedback relating to the BACB Task List for technicians who are pursing board certification. Forty-five minutes of direct observation of the supervisee are provided by the supervisor each week, for a total of one and a half supervisory hours within a 2-week period. During the 45 min of supervision each week, the supervisor monitors the supervisee’s skill of directly implementing ABA therapy with a client on the autism spectrum. The specific areas that are monitored consist of (a) learner focused competencies, which assesses the supervisees’ ability to maintain the client’s dignity and keep the client safe in all situations; (b) data collection competencies, which assesses the supervisee’s ability to immediately and accurately record all necessary data regarding client progress; (c) maladaptive behavior competencies, which monitors the supervisee’s ability to accurately implement the strategies outlined for client goals pertaining to the decrease of maladaptive behavior; (d) reinforcement competencies, which assesses the supervisee’s ability to deliver reinforcement within the guidelines identified for the client; and (e) teaching competencies, which assesses the supervisee’s ability to deliver instructions and provide prompts appropriate for the client (see Appendix D for the Technician Observation Form).

Multiple supervisors tend to supervise technicians due to the way technicians are typically assigned to provide services to at least two clients at any given time, and each client may have a different supervising BCBA (a technician will often have one session with a client in the morning and a second session with a different client in the afternoon). The BACB encourages supervision from multiple supervisors as an additional measure to ensure a robust supervision experience. As a result, supervisees receive supervision hours from multiple supervisors and receive monthly performance feedback in a systematic fashion via a performance scorecard. The monthly performance feedback system was developed by the organization in collaboration with Aubrey Daniels International©, wherein pinpoints were identified that encompassed the requirements for a supervisee conducting direct implementation of ABA therapy with a client. Those requirements consist of the following: (a) meeting scores within a range for therapy implementation observed by a supervisor; (b) meeting the criteria for insurance billing paperwork submitted on time; (c) meeting all professionalism criteria during interactions with clients, parents, co-workers, and supervisors; (d) meeting the organization’s policy for percentage of days present; and (e) meeting the organization’s policy for percentage of days arriving to work on time. Supervisors provide monthly feedback to supervisees on each of the areas listed above, which includes reinforcement for meeting or exceeding expectations and coaching in areas that require improvement (see Appendix E for the technician performance scorecard).

Year 2: BCBA Apprentice

The second 750 h of supervision are reserved for a few highly competitive BCBA Apprentice positions for supervisees who have completed at least 750 h of direct therapy implementation with clients and who have demonstrated competency with therapy implementation skills. The purpose of this portion of supervision is for the supervisee to become fluent with the responsibilities of a BCBA by assisting one’s supervisor with her daily responsibilities of client and technician oversight. Delivery of performance feedback is conducted monthly in a systematic fashion using the same process as described above. However, as a BCBA Apprentice, the pinpointed requirements are adjusted to include higher expectations including the following: (a) assisting one’s supervisor with the clinical oversight of clients, (b) assisting one’s supervisor with monitoring the performance of technicians, (c) assisting one’s supervisor with the development and creation of client treatment plans, (d) assisting one’s supervisor with ensuring clients meet goals identified in treatment plans, (e)meeting the organization’s policy for percentage of days present, and (f) meeting the organization’s policy for percentage of days arriving to work on time (see Appendix F for the BCBA Apprentice performance scorecard).

Supervision during the BCBA Apprentice portion of the supervision process typically occurs in three different ways. The first form of supervision consists of one 30-min supervisee/supervisor meeting each week. The purpose of this supervision meeting is to review the completion of the supervisee’s behavior analytic tasks related to their learners, to review the supervisee’s creation of data sheets, behavior guidelines, programs, and to discuss future objectives for each learner. The second form of supervision consists of one 30-min supervisee/supervisor learner observation each week. During this dual observation, the supervisee conducts an observation of the therapy provided by the technician with the client, and the supervisor provides feedback to the supervisee regarding her observation style and learning opportunities provided to the technician. The third form of supervision consists of one, hour-long team meeting at least every other week where the supervisor facilitates a meeting with all members of a client’s team with assistance from the supervisee.

Small Group Supervision

This supervision is conducted in the form of monthly staff trainings and monthly journal club discussions. During the staff training, supervisees are required to actively participate in a training facilitated by a BCBA on a relevant clinical topic. The training topic varies depending on the relevant clinical training needs from 1 month to another. For journal club discussions, supervisees are required to actively participate in reading and discussing a behavior-analytic journal article and facilitate the journal discussion on a rotating basis with other supervisees. This experience aids in establishing public speaking skills and staff training. Unlike the other forms of supervision (direct implementation and BCBA Apprentice duties), time and effort from a BCBA are required to develop the trainings and prepare for the journal discussions.

Conclusion

Prior to the apprenticeship supervision model, the organization had 39 % of its supervisees in positions that would allow for comprehensive supervised independent fieldwork experiences consisting of both direct and indirect implementation. As a result of the new supervision model, 83 % of supervisees are in BCBA Apprentice positions, which allows for more comprehensive supervision experiences.

The four reasons cited by the organization for restructuring the supervision model were as follows:

Inconsistent learning opportunities for the supervisee regarding behavior-analytic concepts.

The effort associated with the supervisor in providing supervision.

The lack of indirect experience hours available to the supervisees.

The low number of supervisees who continued on as BCBAs within the organization at the conclusion of their supervision.

The apprenticeship supervision model helps to significantly remediate these problems in the following four ways. First, because the supervisor’s objective is to provide the supervisee with applied learning opportunities that put concepts into practice, rather than focusing on teaching the initial acquisition of concepts and terminology, the supervisee no longer receives inconsistent learning opportunities regarding behavior-analytic concepts. Second, the effort associated with planning and preparing to supervise on the part of the supervisor has dramatically decreased because the supervisees’ learning opportunities are directly related to the task of shadowing and assisting the supervisor and learning in the moment when new practical situations arise. As a result, preparation time on the part of the supervisor has dramatically decreased. Third, the previous supervision model did not typically allow for the development of skills such as acquisition writing, programming, treatment plan writing, behavior deceleration programming, and data analysis. However, with the execution of the apprenticeship supervision model, the supervisee has the opportunity for submersion into indirect tasks through the continuous modeling and oversight of their supervising BCBA. Last, the apprenticeship model sets a structure and framework for the organization’s supervisees to gain the practical skills needed in order to transition into a BCBA position within the organization in the future. There is now a more clearly outlined path for clinical advancement opportunities, which will help the organization maintain the BCBAs which it cultivated.

Some additional important benefits that have resulted from the implementation of the apprenticeship supervisor’s model are an increased expertise in the oversight of each client’s case, an increase in the number of clients for whom the organization can provide services, an increase in profit to the organization, and an increase in employee satisfaction. This model creates an increase in expertise in the oversight of each client’s case because, as described previously, the BCBA Apprentice is a supervisee who is enrolled in behavior analysis coursework; therefore, the combined team of a supervisor (who is a BCBA) and a supervisee (who is a future BCBA) is available to collaborate and brainstorm on each client’s case. Theoretically, this results in increased progress for clients in comparison to a model where a BCBA has a less skilled and educated assistant, or no assistant at all. The second advantage to the apprenticeship model is the ability to provide services to a larger number of individuals on the autism spectrum. Previous to the implementation of this model, the average caseload of a BCBA within the organization was five clients. With the application of this model, each BCBA is equipped with the BCBA Apprentice who serves as the resource needed to manage a caseload of eight clients. As of the writing of this article, this increase in caseload per BCBA results in the ability to enroll an additional 60 clients on the autism spectrum. The third additional advantage to the apprenticeship model is the revenue generated for the organization. The apprenticeship supervision model generates a revenue of $25,000 per more BCBA than the previous supervision model. This change in revenue is contributed to the increased caseload of 2.5 additional clients per BCBA. Based on the number of BCBAs who currently hold a caseload of clients within the organization (which at the writing of this article is 19 BCBAs), the apprenticeship model results in additional revenue of $475,000 annually. This equates to an additional cost savings of approximately $10,000 per client. For applied practitioners, this is most relevant because it provides sustainability to an organization and allows the opportunity to provide services to the highest number of clients while maintaining high quality. Last, the social validity of the apprenticeship model is important to the organization; therefore, BCBAs who hold a caseload of clients were asked to rank their preference in providing supervision through the BCBA Apprentice model in comparison to the organization’s previous supervision model. Ninety-four percent of BCBAs indicated preference for the apprenticeship model of supervision.

One disadvantage associated with the apprenticeship supervision model was in regard to feedback from the supervisees themselves. Sixteen percent of supervisees noted a preference for the previous supervision model in comparison to the apprenticeship supervision model. The reason identified was the prior emphasis on academic training regarding the principals of behavior in comparison to the apprentice supervision model which puts emphasis on training associated with day-to-day practice as a BCBA and only highlights training on principles of behavior as applicable to specific client situations. An additional question worth pursuing would have been the degree of satisfaction each supervisee had with the academic knowledge they had gained from the academic institution in which they were enrolled. The desire for more academic training may be an indication of the quality of each supervisee’s academic experience. Despite this feedback, the vast number of advantages of the apprenticeship supervisory model outweigh the organization’s previous model.

There is a growing need for experienced and expert BCBA practitioners to work with individuals with autism. That increased need for BCBAs has resulted in the necessity to identify high-quality and efficient supervisory models. The strengths associated with the apprenticeship supervisory model contribute to benefits for clients, supervisees, and supervisors; therefore, this is a recommended supervisory model for ABA organizations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 260 kb)

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Breanne K. Hartley, Phone: 317-249-2242, Email: breanneh@littlestarcenter.org

William T. Courtney, Phone: 317-249-2242, Email: timc@littlestarcenter.org

Mary Rosswurm, Phone: 317-249-2242, Email: maryr@littlestarcenter.org.

Vincent J. LaMarca, Phone: 317-249-2242, Email: vincel@littlestarcenter.org

References

- (BACB). (2014). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. Retrieved from http://bacb.com/wpcontent/uploads/2016/03/160321-compliance-code-english.pdf.

- BACB. (2015). Experience standards. Retrieved from http://bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/150824-experience-standards-english.pdf.

- BACB. (n.d.). Obtaining BCBA certification. Retrieved from http://bacb.com/bcba-requirements/.

- Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1, 91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Behavior Analysis Accreditation Board (BAAB), Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI). (2016). Accreditation handbook. Retrieved from https://baab.abainternational.org/media/110571/baab_accreditation_handbook.pdf.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB). (2014). Applied behavior analysis treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Practice guidelines for healthcare funders and managers. Retrieved from http://bacb.com/wpcontent/uploads/2015/07/ABA_Guidelines_for_ASD.pdf.

- Burning Glass Technologies. (2015). US behavior analyst workforce: understanding the national demand for behavior analysts. Retrieved from the Behavior Analyst Certification Board Website: http://bacb.com/workforce-demand-report/.

- Carr JE. The evolution of certification standards in behavior analysis. New Orleans: Presentation at the annual autism conference, Association for Behavior Analysis International; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney T, McKee L, Woolf S, Ross R, Zarcone J. Contracting with insurance companies to provide ABA. New Orleans: Presentation at the annual autism conference, Association for Behavior Analysis International; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield TS. In dreams begin responsibility: why and how to measure the quality of graduate training in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8:123–133. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Reed DD, Smith T, Belisle J, Jackson RE. Research rankings of behavior analytic graduate training programs and their faculty. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8:7–15. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0057-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friman PC. My heroes have always been cowboys. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8(2):138–139. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0068-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagon KA. A behavior analytic introduction to the global autism public health initiative and autism researchers without borders. New Orleans: Presentation at the annual autism conference, Association for Behavior Analysis International; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, Valentino AL, LeBlance LA. Recommended practices for individual supervision of aspiring behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shook GL, Favell JE. The behavior analyst certification board and the profession of behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2008;1:44–48. doi: 10.1007/BF03391720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shook GL, Johnston JM, Mellichamp FH. Determining essential content for applied behavior analyst practitioners. Behavior Analyst. 2004;27:67–94. doi: 10.1007/BF03392093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Study suggests insurance mandates help close gaps in autism care. (2016). Retrieved from http://autismspeaks.org/science/science-news/study-suggests-insurance-mandates-help-close-gaps-autism-care

- Turner LB, Fischer AJ, Luiselli JK. Towards a competency-based, ethical, and socially valid approach to the supervision of applied behavior analytic trainees. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 260 kb)