Abstract

A 30-day old Gir calf was brought to Veterinary Polyclinic with symptoms of high fever, dullness, dyspnea, pale mucus membrane and haemoglobinuria. Blood sample was collected and microscopic examination of thin blood smear confirmed the case of acute babesiosis. It was further confirmed by polymerase chain reaction that amplified an approximately 410 bp portion of the ssu-rDNA of Babesia spp. The calf was managed with diminazene aceturate @5 mg/kg (Berenil) intramuscularly followed by supportive therapy including intravenous infusions. The present study reports a rare case of bovine babesiosis, its clinical variants, diagnosis, hematology and therapeutic management.

Keywords: Babesiosis, Calf, Diminazene aceturate, Gir, Haemoglobinuria, PCR

Introduction

Babesia bigemina is one of several Babesia spp. known to cause bovine babesiosis which is an economically important intra erythrocytic tick borne disease of tropical and subtropical parts of the world including India (Sharma et al. 2013). Due to babesiosis, India suffers losses of about 57.2 million US dollars annually in livestock (McLeod and Kristjanson 1999). Babesia bigemina is principally transmitted by one host tick i.e. Boophilus spp. Usually young calves are resistant to babesiosis infection due to reverse age resistance. Inutero transmissions have been reported, but are infrequently encountered in calves (Karunakaran et al. 2011). The disease is characterized by inappetence, fever, increased respiratory rate, anaemia and haemoglobinuria. This paper highlights the diagnosis of a case of severe B. bigemina infection in a 1 month old Gir calf by traditional as well by molecular based technique and its successful therapeutic management.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

A one month old Gir calf was presented to the Teaching Veterinary Clinical Complex, College of Veterinary Science & A.H., Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh, Gujarat with a history of passing coffee colored urine, anorexia, emaciation, loss of weight, fever, increased respiratory rate and anaemia. On clinical examination the animal had rectal temperature of 104.2 °F and slight pale mucus membrane. Based on the clinical outcomes, the calf was suspected for haemoprotozoan infection. Subsequently, peripheral blood was collected aseptically (3 ml aliquot in EDTA coated vacutainer) to check haemoparasite, isolation of genomic DNA and for evaluation of various haematological parameters. Additionally, prescapular lymph node was aspirated to check presence of haemoparasite, if any.

Conventional parasitological method

Thin and thick blood smears were prepared and subjected to Giemsas staining method following the standard protocol. Briefly, the blood smears were air dried, fixed in methanol, stained with Giemsa, and examined under oil immersion lens of compound binocular microscope (100×) for the detection of haemoprotozoan parasite. Lymph node aspirate smear was stained following the above said protocol. The body hair coat was carefully searched for the presence of acarine parasites, but no ticks were detected on external visualization.

Haematological analysis

The hematology of the whole blood was done with fully automated analyzed haematology system (Mindrey, China) as per instructions of the manufacturer.

Molecular diagnostic method

Preparation of DNA template

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood collected in EDTA coated vacutainer using GENEJET whole blood genomic DNA purification mini kit as per the given protocol (Thermo Scientific, Lithuania). The genomic DNA of infection free leucocytes separated from the blood of a 3-day-old neonatal bovine calf was included as negative control while genomic DNA isolated from B. bigemina infected erythrocytes of clinically infected cattle was used as positive control.

PCR protocol

The PCR assay was optimized targeting a portion of ssu-rDNA of Babesia spp. (Olmeda et al. 1997). The sequences of the primers were as follows:

Piro A Forward: 5′-AATACCCAATCCTGACACAGGG-3′

Piro B Reverse: 5′-TTAAATACGAATGCCCCCAAC-3′

PCR assay in a final volume of 25 µL was carried out in a PCR thermal cycler (Applied Biosystem, USA). The master mix consisted of 2.5 µL of Dream Taq buffer (Thermo Scientific, USA), 0.5 µL of 10 mM dNTP mix (Thermo Scientific, USA), 1 µL each (20 pmol) of the primers, 0.2 µL of recombinant Taq DNA Polymerase (Thermo Scientific, USA) and 1 µL of template DNA isolated from infected calf blood. The volume was made up to 25 µL with nuclease-free water. The PCR cycling conditions were set in automated thermal cycler with the following programme: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 60 s, annealing at 60 °C for 45 s. and extension at 72 °C for 30 s and the final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The amplified PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis on a 1.2 % agarose gel and visualized using gel documentation system (Vilverlourmat, Bioprint ST4, Germany).

Treatment

The affected calf was treated with diminazene aceturate 5 mg/kg body weight intramuscularly along with supportive therapy i.e. analgesics, antihistamines and B complex along with intravenous infusions.

Results

Blood smear examination

The freshly prepared Giemsas stained thin blood smear revealed intra erythrocytic merozoites of parasites which were pyriform shaped, elongate, slightly bigger and were confirmed as B. bigemina. Giemsa stained blood smear revealed 4–5 % RBC erythrocytes infected with B. bigemina piroplasm. Lymph node aspirate smear did not reveal any haemoparasite or parasitic stages (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Intra erythrocytic Babesia bigemina organism (in pair) under oil immersion lens (×1000)

Haematological parameters

Hematological studies revealed 5.0 g % Hb, 5.22 × 1012/L total RBC, 19 % PCV, 9.5 × 109/L total WBC, 35 fL MCV and 302 × 109/L platelet.

Molecular parasitology assay

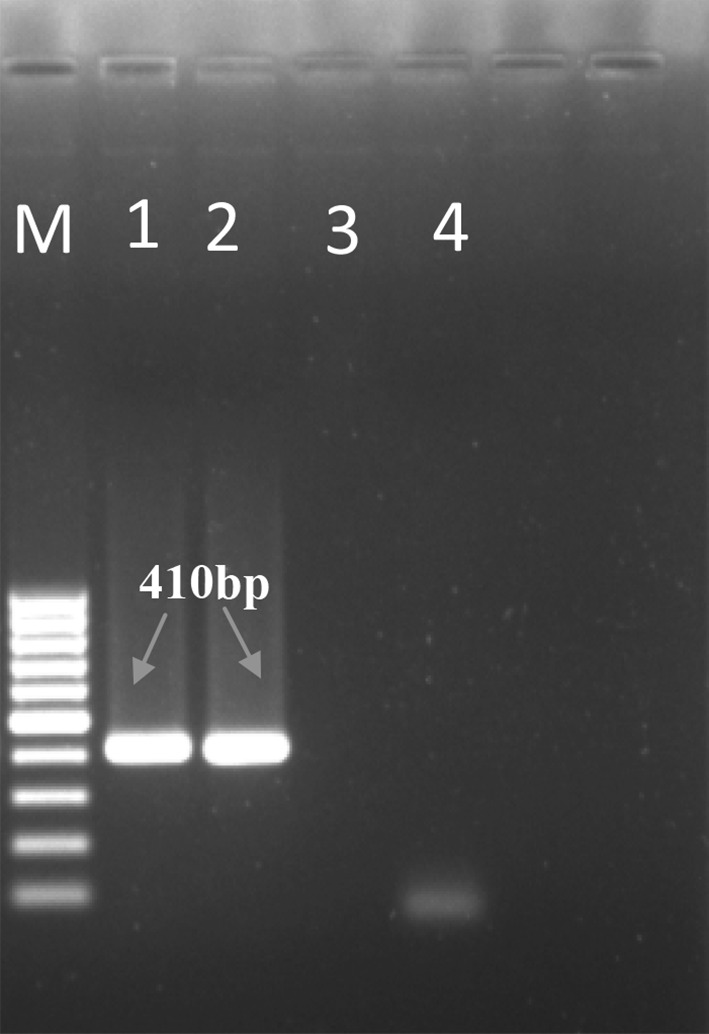

PCR assay revealed a fragment of size approximately 410 bp in 1.2 % agarose gel specific for ssu-DNA of Babesia spp. after specific primers directed amplification. In negative control there was no amplification (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Agarose gel (1.2 %) electrophoresis showing amplified DNA from Babesia bigemina. Lane M Molecular size marker 100 bp. Lane 1 Amplification of B. bigemina genomic DNA from the blood of animal positive for infection (positive control). Lane 2 Amplification of B. bigemina genomic DNA from the blood of calf infected for B. bigemina. Lane 3 No amplification for host leucocyte DNA. Lane 4 No amplification using nuclease free water as negative control

Treatment follow-ups

The affected animal became afebrile by 48 h after therapy. After 1 week, the peripheral blood smear examination was found to be negative for Babesia organisms. Hematological analysis revealed the various haematological parameters were within normal range. The animal showed good response to the treatment regimen.

Discussion

The clinical examination of the Gir calf revealed the similar observations as reported by earlier workers (Venu et al. 2013; Tufani et al. 2009; Bikane et al. 2001).

Laboratory investigation of peripheral blood revealed suppressed haematological indices. These results further confirmed that the calf suffered from severe anemia and moderate leucopenia. Anaemia was possibly due to the destruction of RBC by emerging parasites, increased phagocytic activity of non-infected erythrocytes by reticuloendothelial cells and suppression of erythropoises. The present findings were in conformity with various workers (Lakshmi et al. 2010; Aulakh et al. 2005). Microscopic examination of Giemsas stained thin blood smear revealed intra erythrocytic pyriform shaped, elongated merozoites confirmed the case as B. bigemina. The observations are in accordance with the previous reports (Soulsby 1982) and the parasitaemia was around 5 %. PCR assay further confirmed the infection to be babesiosis.

Based on the confirmative diagnosis, the calf was treated immediately with diminazene aceturate 5 mg/kg body weight intramuscularly along with supportive therapy. The drug is effective and blocks the replication of DNA of the parasite. Imidocarb dipropionate is the drug of choice for treatment of bovine babeisois followed by diminazene aceturate, with 100 and 90 % efficacy at 10 day post infection respectively (Niazi et al. 2008). In the present investigation, the calf showed virtuous response to diminazene aceturate as obvious from blood picture at 7 day post infection.

Earlier several workers from India have reported babesiosis in young calves (Vairamuthu et al. 2012; Karunakaran et al. 2011; Mallick et al. 1980). Yeruham et al. (2003) reported occurrence of B. bovis infection in 2-day old calf in Israel. In the present study, the age of the infected Gir calf was 30 days. There is an age-related immunity to primary infection of cattle with B. bovis and B. bigemina (Riek 1963). Young calves display a robust innate immunity compared to adult cattle (Goff et al. 2001). The average age at which calves in enzootic areas become infected is 11 weeks, but at this early age clinical signs and pathological changes are mild and short lived (Radostits et al. 2000).

Intrauterine infection of babesiosis had been reported, but rare (Jorgensen 2008). Since the incubation period described for clinical cases of baesiosis is 1–3 weeks, the plausible reason for the calf to get infected in the present study might be intrauterine transmission. But based on the prior history, the mother of the calf showed neither babesiosis infection nor any tick infestation. Hence, in the present case, the apparent source of infection occurred after the birth might be attributed to tick bite. The same observation was reported earlier by Mallick et al. (1980) who reported B. bigemina infection in a 14-day old calf.

In endemic areas of bovine babesiosis, calves develop a certain degree of immunity, related both to colostral-derived antibodies and age that persists for about 6 months (Jorgensen 2008). At high levels of tick transmission, all newborn calves will become infected with Babesia by 6 months of age and subsequently develop immunity.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study reveals a rare case of an acute babesiosis in a Gir calf, its diagnosis by traditional optical microscopy based technique complemented with molecular technique like PCR targeting the ssu-rDNA of the Babesia spp. and its successful therapeutic management. Presently there is no report of occurrence of babesiosis in Gir calf. This is a first report of its kind and hence placed on record.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the officer in In-charge, TVCC, Veterinary College, Junagadh, Gujarat and Principal and Dean, College of Veterinary Science & A.H., Junagadh for providing the necessary facilities.

Contributor Information

Biswa Ranjan Maharana, Email: drbiswaranjanmaharana@gmail.com.

Binod Kumar, Email: drkumarbinod@gmail.com.

Nitinkumar Devrajbhai Hirani, Email: hiranink@yahoo.co.in.

References

- Aulakh GS, Singla LD, Kaur P, Alka A. Bovine babesiosis due to Babesia bigemina: haematobiochemical and therapeutic studies. J Anim Sci. 2005;75(6):617–622. [Google Scholar]

- Bikane AU, Narladkar BW, Anantwar LG, Bhokre AP. Epidemiology, clinico-pathology and treatment of babesiosis in cattle. Indian Vet J. 2001;78:726–729. [Google Scholar]

- Goff WL, Johnson WC, Parish SM, Barrington GM, Tuo W, Valdez RA. The age-related immunity in cattle to Babesia bovis infection involves the rapid induction of interleukin-12, interferon-gamma and inducible nitric oxide synthase mRNA expression in the spleen. Parasite Immunol. 2001;23:463–471. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2001.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen WK. The Merck veterinary manual. 9. Whitehouse Station: The Merck & Co Inc; 2008. pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Karunakaran S, Pillai UN, Kuriakose AM, Aswathy G. Babesia bigemina infection in a 20 day old calf. J Indian Vet Assoc Kerala. 2011;9(1):49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi RN, Sreedevi C, Annapurna P, Aswini Kumar K. Clinical management and haemato-biochemical changes in babesiosis in buffaloes. Buffalo Bull. 2010;29(2):92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mallick KP, Dwivedi SK, Malhotra MN. Babesiosis in a new born indigenous calf. Indian Vet J. 1980;57(8):686–687. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod R, Kristjanson P. Final Report of Joint ESYS/International Livestock Research Institute/Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research Tick Cost Project-Economic Impact of Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases to Livestock in Africa, Asia and Australia. Nairobi: International Livestock Research Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Niazi N, Khan MS, Avais M, Khan JA, Pervez K, Ijaz M. Study on Babesiosis in calves at livestock experimental Station Qadirabad and adjacent areas, Sahiwal (Pakistan) Pak J Agric Sci. 2008;45(2):209–211. [Google Scholar]

- Olmeda AS, Armstrong PM, Rosenthal BM, Valladares B, del Castillo A, de Armas F, Miguelez M, Gonzalez A, Rodriguez Rodriguez JA, Spielman A, Telford SR., 3rd A subtropical case of human babesiosis. Acta Trop. 1997;67:229–234. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(97)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radostits AM, Gay CC, Blood DC, Hinchcliff KW. Veterinary medicine. A text book of the diseases of cattle, sheep, pigs and horses. 9. London: W B Saunders Co., Ltd.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Riek RF. Immunity to babesiosis. In: Garnham PCC, Pierce AE, Riott I, editors. Immunity to protozoa. Oxford: Blackwell; 1963. pp. 160–179. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Singla LD, Tuli A, Kaur P, Batth BK, Javed M, Juyal PD. Molecular prevalence of Babesia bigemina and Trypanosoma evansi in dairy animals from Punjab, India, by duplex PCR: a step forward to the detection and management of concurrent latent infections. Biomed Res Int. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/893862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulsby EJL. Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals. 7. London: ELBS Baillire Tindall; 1982. p. 706. [Google Scholar]

- Tufani NA, Hafiz A, Malik HU, Peer FU, Makdoomi DM. Clinico-therapeutic management of acute babesiosis in Bovine. Intas Polivet. 2009;10(1):49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Vairamuthu S, Pazhanivel N, Suresh RV, Balachandran C. Babesia bigemina in a 20 day old non-descript calf: a case. Indian J Field Vet. 2012;7(4):69. [Google Scholar]

- Venu R, Sailaja N, Rao KS, Jayasree N, Vara Prasad WLNV. Babesia bigemina infection in a 14-day old Jersey crossbred calf: a case report. J Parasit Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s12639-013-0338-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeruham I, Avidar Y, Aroch I, Hadani A. Intra-uterine infection with Babesia bovis in a 2-day-old calf. J Vet Med Series B. 2003;50(2):60–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2003.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]