Abstract

Stimulant abuse is a serious public health issue for which there is no effective pharmacotherapy. The serotonin2C [5-hydroxytryptamine2C (5-HT2C)] receptor agonist lorcaserin decreases some abuse-related effects of cocaine in monkeys and might be useful for treating stimulant abuse. The current study investigated the effectiveness of lorcaserin to reduce self-administration of either cocaine or methamphetamine and cocaine-induced reinstatement of extinguished responding. Four rhesus monkeys responded under a progressive-ratio (PR) schedule in which the response requirement increased after each cocaine infusion (32–320 μg/kg/infusion). A separate group of four monkeys responded under a fixed-ratio (FR) schedule for cocaine (32 μg/kg/infusion) and reinstatement of extinguished responding was examined following administration of noncontingent infusions of cocaine (0.1–1 mg/kg) that were combined with response-contingent presentations of the drug-associated stimuli. Finally, three monkeys responded under a FR schedule for methamphetamine (0.32–100 μg/kg/infusion). Lorcaserin (3.2 mg/kg) significantly decreased the final ratio completed (i.e., decreased break point) in monkeys responding under the PR schedule and reduced the reinstatement of responding for drug-associated stimuli following a noncontingent infusion of cocaine; these effects did not appear to change when lorcaserin was administered daily. The same dose of lorcaserin decreased responding for methamphetamine in two of the three monkeys, and the effect was maintained during daily lorcaserin administration; larger doses given acutely (10–17.8 mg/kg) significantly decreased responding for methamphetamine, although that effect was not sustained during daily lorcaserin administration. Together, these results indicate that lorcaserin might be effective in reducing cocaine and methamphetamine abuse and cocaine relapse at least in some individuals.

Introduction

Abuse of stimulant drugs is a serious problem in the United States, with an estimated 1.5 million people reporting current cocaine abuse and 0.5 million people reporting current methamphetamine abuse [Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, “Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health” (http://www.samhsa.gov/data/)]. Of particular concern is that no pharmacotherapies are approved for stimulant abuse, and behavioral therapies are the primary treatment. For other drug classes (e.g., opioids), a number of strategies are used to treat abuse, including agonist replacement therapies (e.g., methadone) and treatment with a pharmacological antagonist (e.g., naltrexone). While those strategies are effective for some drugs, they have not been useful for treating stimulant abuse; consequently, other potential treatments are being investigated.

Although stimulant drugs differ slightly in their mechanism of action, they all increase dopamine neurotransmission, which is primarily responsible for their abuse (Ritz et al., 1987). One strategy for treating stimulant abuse is to reduce dopamine neurotransmission, and the dopamine system has been a target for medications development with both dopamine receptor agonists and antagonists. Because those efforts have not resulted in approved pharmacotherapies, other systems that impinge on the dopamine system are being examined for their potential to reduce stimulant abuse. Serotonin [5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] systems can modulate dopamine neurotransmission, and drugs acting on these systems are being considered for treatment of stimulant drug abuse, including 5-HT2C receptor agonists (Howell and Cunningham 2015), which can decrease cocaine self-administration and the reinstatement of responding for cocaine (Grottick et al., 2000; Burmeister et al., 2004; Burbassi and Cervo 2008; Cunningham et al., 2011; Manvich et al., 2012; Rüedi-Bettschen et al., 2015).

One 5-HT2C receptor agonist, lorcaserin (Belviq®), is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat obesity in humans. Although it binds to multiple 5-HT receptor subtypes and to the 5-HT transporter, lorcaserin is most selective for 5-HT2C receptors (Thomsen et al., 2008). Results of behavioral studies are consistent with in vitro data, with 5-HT2C receptor-mediated behaviors (i.e., yawning) observed after acute administration of small doses of lorcaserin (Serafine et al., 2015; Collins et al., 2016), and behavioral effects mediated by 5-HT2A (i.e., head twitching) and 5-HT1A (i.e., forepaw treading) receptors apparent only after acute administration of larger doses (Serafine et al., 2015). Importantly, lorcaserin was shown to attenuate self-administration of cocaine (Collins et al., 2016; Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016) and nicotine (Levin et al., 2011; Higgins et al., 2012, 2013), suggesting that it might be effective in reducing stimulant abuse. In monkeys, this effect of lorcaserin did not appear to result from a pharmacokinetic interaction because 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin decreased responding for cocaine without altering plasma levels of cocaine (Collins et al., 2016). Although 3.2 mg/kg increased yawning in monkeys, larger doses were required to decrease activity without significantly changing 23 other directly observable signs, suggesting that unwanted effects would be limited at doses that alter cocaine self-administration (Collins et al., 2016). Finally, tolerance does not develop to the effects of lorcaserin on cocaine self-administration (Collins et al., 2016), further supporting the use of lorcaserin to treat cocaine abuse.

In the current study, the generality of these previous findings was tested using three additional procedures, which were selected because they are predictive of drug abuse and relapse in humans; however, until there are successful pharmacotherapies for stimulant abuse there will be no reference drugs to which lorcaserin and other candidate medications can be compared (Howell and Cunningham 2015). First, because downward shifts in fixed-ratio (FR) dose-effect curves, such as those obtained when lorcaserin was studied with cocaine (Collins et al., 2016), can be challenging to interpret, the current studies examined the capacity of lorcaserin to alter the reinforcing effectiveness of multiple cocaine doses under a progressive-ratio (PR) schedule; the development of tolerance was monitored by administering lorcaserin daily for 14 days. Second, reinstatement of cocaine self-administration was used to model relapse to drug use, a major challenge when treating drug abusers. In reinstatement procedures, stimuli that were previously paired with cocaine delivery were presented alone or together with a noncontingent infusion of cocaine, resulting in reinstatement of extinguished responding. Lorcaserin was given acutely and daily for 5 days to examine its ability to reduce the reinstatement of extinguished responding in cocaine-experienced monkeys. Finally, to test whether lorcaserin might be useful for treating abuse of stimulant drugs with mechanisms of action that are slightly different from that of cocaine (inhibition of monoamine uptake), lorcaserin was given daily to monkeys responding under a FR schedule for methamphetamine (inhibition of monoamine uptake and stimulation of monoamine release). Experimental parameters that differed between monkeys responding for cocaine and those responding for methamphetamine were determined to be optimal for each stimulant drug, thereby maximizing the productivity and efficiency of each experiment.

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

Twelve adult rhesus monkeys were used in these studies. Three males (PE, BO, DU) and 1 female (RO), weighing between 8 and 10 kg, responded under a PR schedule for cocaine. A separate group of two male monkeys (MU, CH) and three female monkeys (DAI, DAH, GA) weighed between 6.5 and 10.5 kg and contributed to studies on reinstatement of cocaine self-administration. Three other male monkeys (AC, GU, LR) weighing between 8.5 and 12 kg responded under a FR schedule for methamphetamine. Monkeys were housed individually on a 14-hour light and 10-hour dark cycle. They had free access to water in their home cage and received primate chow (Harlan Teklad, High Protein Monkey Diet, Madison, WI), fresh fruit, and peanuts daily. Monkeys were maintained, and all experiments were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and with the National Research Council (2011) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th edition (2011).

Surgery.

Indwelling venous catheters were placed according to methods described elsewhere (Wojnicki et al., 1994). Briefly, monkeys were initially sedated with 10 mg/kg ketamine s.c. (Fort Dodge Laboratories, Fort Dodge, IA), and then intubated and maintained on 2 l/min oxygen and isoflurane anesthesia (Butler Animal Health Supply, Grand Prairie, TX). A polyurethane catheter (SIMS Deltec Inc., St. Paul, MN) was implanted in a vein (e.g., jugular or femoral) and tunneled subcutaneously to the midscapular region of the back, where it was connected to a vascular access port (Access Technologies, Skokie, IL). Penicillin B&G (40,000 IU/kg) and meloxicam were given postoperatively.

Apparatus.

During sessions, monkeys were seated in commercially available chairs (Model R001; Primate Products, Miami, FL), which were placed in ventilated, sound-attenuating chambers. Response panels were mounted on the front wall of each chamber and contained two response levers located directly below stimulus lights that could be illuminated red or green. Vascular access ports were connected to 30- or 60-ml syringes using 20-g Huber-point needles (Access Technologies) and 185-cm extension sets (Abbott Laboratories, Stone Mountain, GA). Syringes were placed in syringe drivers (Razel Scientific Instruments Inc., Stamford, CT) located outside the chamber. Experimental events were controlled and data were recorded by a computer using Med-PC IV software (Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT).

Cocaine Self-Administration.

Four monkeys with a history of self-administering 32 μg/kg/infusion cocaine under a FR-30:timeout (TO) 180-second schedule (Collins et al., 2016) responded under a PR schedule in which the response requirement increased after each infusion. Monkeys were seated in chairs twice daily. The first time occurred 90 minutes before sessions when they received either saline or lorcaserin intragastrically (i.g.). They returned to their home cage and were again placed in the chair just before the beginning of the 90-minute session. Once inside the chamber, a loading infusion was administered to fill the catheter, and the session began 1 minute after the start of the loading infusion with a noncontingent priming infusion of 32 μg/kg cocaine and a concomitant presentation of the cocaine-associated stimuli, including 5-second illumination of a red light above the active lever. After 5 seconds, the red light was extinguished and the green light located above the active lever was illuminated, which signaled drug availability. Responding on the active lever (counterbalanced across monkeys) resulted in the delivery of cocaine (3.2, 10, 32, 100, or 320 μg/kg) or saline and a 5-second presentation of the cocaine-associated stimuli. For delivery of the first infusion, monkeys were required to emit 50 responses. The response requirement increased exponentially after each infusion according to the following equation: ratio = [5e(infusion number × 0.2)] − 5, yielding ratios of 50, 62, 77, 95, 118, 145, 178, 219, 268, 328, 402, 492, 603, 737, 901, 1102, etc. (Richardson and Roberts, 1996). A TO of 180 seconds followed each infusion during which time the chamber was dark and responses were recorded but had no scheduled consequence. At the end of the TO, the green light above the active lever was again illuminated and cocaine was available. Throughout the session, responses emitted on the inactive lever were recorded but had no scheduled consequence. Sessions ended when 40 minutes elapsed since completion of the last ratio or when 4 hours elapsed since the start of the session.

When monkeys received saline i.g. daily 90 minutes before sessions in which cocaine was available for self-administration, responding for cocaine was considered stable in an individual monkey when the number of infusions obtained did not differ by more than two over two consecutive sessions. On the day after these stability criteria were satisfied, 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin i.g. replaced saline 90 minutes before the start of the session. In a previous study, multiple doses of lorcaserin were studied in monkeys self-administering 32 μg/kg/infusion cocaine under a FR-30:TO 180-second schedule of reinforcement; the dose of lorcaserin that was determined to be the smallest effective dose was used in the current study with varying doses of cocaine (Collins et al., 2016). The two subsequent sessions were identical to sessions that preceded lorcaserin administration. On the third day after monkeys received lorcaserin, the dose of cocaine available for self-administration was changed and the entire process was repeated until dose-effect curves for cocaine (3.2–320 μg/kg/infusion) were determined with and without lorcaserin (monkey DU did not complete the 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin treatment at the 3.2 μg/kg/infusion dose of cocaine for technical reasons).

After the acute effects of lorcaserin on the cocaine dose-effect curve were determined, the dose of cocaine available for self-administration was changed to 32 μg/kg/infusion with saline given i.g. 90 minutes before sessions. When the stability criteria had once again been satisfied, 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin replaced saline before sessions for 14 consecutive days; otherwise, experimental conditions were unchanged. To determine whether any changes were reversed when lorcaserin treatment ended, two additional sessions were conducted in which saline replaced lorcaserin. Repeated treatment with lorcaserin was only evaluated in three monkeys (PE, RO, BO).

Cocaine-Primed Reinstatement.

A separate group of five monkeys also had a history of self-administering 32 μg/kg/infusion cocaine under a FR-30:TO 180-second schedule of reinforcement (Collins et al., 2016) and were used for reinstatement studies. These studies consisted of three distinct types of sessions (baseline, extinction, and reinstatement) with either saline or lorcaserin administered i.g. 90 minutes before all sessions. Baseline sessions were identical to those described previously for cocaine self-administration except that monkeys responded for 32 μg/kg/infusion cocaine under a FR-30:TO 180-second schedule of reinforcement and daily sessions ended after 90 minutes. When responding for cocaine stabilized (≤20% difference in number of responses for cocaine across three sessions with no increasing or decreasing trend), extinction conditions were introduced. During these 90-minute sessions, responding was recorded; however, infusions were not delivered and cocaine-associated stimuli were not presented. These conditions remained in place for at least three sessions and until the total amount of responding decreased to <20% of cocaine-reinforced responding that was observed during the previous baseline period. Once the extinction criteria were satisfied, a reinstatement session was conducted under one of the following three conditions: 1) reintroduction of the cocaine-associated stimuli alone; 2) noncontingent administration of cocaine; or 3) reintroduction of the cocaine-associated stimuli and noncontingent administration of cocaine. Saline or one of three doses of cocaine (0.1, 0.32, or 1 mg/kg) was manually delivered through the vascular access port, followed by a 5 ml saline flush to ensure that the entire dose was administered. Reinstatement test sessions began immediately after the noncontingent injection and were identical to extinction sessions or to baseline cocaine self-administration sessions except that no infusions were delivered (i.e., the green light that signaled cocaine availability was reintroduced, and responding on the previously cocaine-reinforced lever resulted in a 5-second presentation of the cocaine-associated stimuli). Subsequently, monkeys were returned to baseline conditions (32 μg/kg/infusion cocaine; FR-30:TO 180-second) for at least five sessions and until stability criteria were met. The effectiveness of lorcaserin to inhibit reinstatement of responding was determined by giving 0.32, 1.0, or 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin instead of saline i.g. 90 minutes before sessions. On separate occasions, each dose of lorcaserin was studied during reinstatement sessions in which the cocaine-associated stimuli were presented alone or in combination with noncontingent cocaine (0.1, 0.32, or 1 mg/kg). The effects of lorcaserin were not evaluated during sessions in which noncontingent cocaine was administered in the absence of the cocaine-associated stimuli. Upon completing studies of the acute effects of lorcaserin on the reinstatement of extinguished responding for cocaine, the effects of repeated treatment with 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin were determined. In contrast to acute studies in which lorcaserin was administered 90 minutes before the reinstatement test session, 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin was administered 90 minutes before each of four extinction sessions, as well as the reinstatement test session, which always occurred on day 5 of lorcaserin treatment.

Methamphetamine Self-Administration.

A separate group of three monkeys had limited self-administration history prior to this study and responded under a FR-30:TO 60-second schedule to receive infusions of methamphetamine. Initially, experimental parameters were identical in monkeys responding for cocaine and methamphetamine; however, those conditions did not maintain reliable responding for methamphetamine. Consequently, the parameters were changed until responding for methamphetamine was stable, although those parameters were different from those used for cocaine (current study; Collins et al., 2016).

When monkeys were placed in the chamber, a loading infusion filled the catheter. Sessions were divided into four cycles beginning with a 5-minute TO during which the chamber was dark and responding had no programmed consequence. The end of the TO and the start of the 20-minute response period was signaled by the delivery of a noncontingent priming infusion along with illumination of the red light above the active lever for 5 seconds. When both the priming infusion and the stimulus presentation ended, the green light above the active lever was illuminated and 30 consecutive responses on that lever initiated the infusion of methamphetamine, a 5-second presentation of the red stimulus light, and a 60-second timeout. The unit dose of methamphetamine increased across cycles in 1/2 log unit increments. The dose range was determined for individual monkeys such that the unit dose available on the third cycle produced, on average, the highest rates of responding in that subject. The concentration of drug remained the same throughout the session and across monkeys; to obtain different doses, the duration of the infusion increased across cycles. In addition, to account for differences in body weight, infusion duration varied across individuals and within an individual across days. Overall, infusion duration ranged from 0.47 to 0.68 seconds during the first cycle and from 15.2 to 21.9 seconds during the fourth cycle. Each cycle lasted 25 minutes.

Monkeys received saline i.g. daily 90 minutes before sessions. Responding for methamphetamine was considered stable when response rates obtained during the third cycle did not exceed ±20% of mean rates obtained during that cycle for three consecutive sessions with no increasing or decreasing trend, and rates obtained during the first cycle of each session were <10% of rates obtained during the third cycle of that session. When these stability criteria were satisfied, 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin (i.g.) replaced saline 90 minutes before sessions in which methamphetamine was available for self-administration; lorcaserin was administered daily for 14 consecutive days followed by 2 days during which saline was given before sessions and methamphetamine was available for self-administration. Upon completion of these 16-day studies and before other doses of lorcaserin were examined, saline replaced methamphetamine until response rates in each cycle were <20% of those maintained by methamphetamine for three consecutive sessions. Thereafter, methamphetamine was again available for self-administration with saline given 90 minutes before sessions. At this point in the experiment, the methamphetamine dose-effect curve shifted rightward for one monkey (LA); to satisfy the stability criteria for methamphetamine listed previously, the dose range of methamphetamine was increased by 1/2 log unit and was used for monkey LA for the remainder of the experiment. For the other two monkeys, the dose range of methamphetamine did not change at any time during these studies. When responding for methamphetamine was stable under these conditions, a larger dose of lorcaserin (10 mg/kg) was given i.g. 90 minutes before sessions for 14 consecutive days followed by 2 days during which saline was given before sessions and methamphetamine was available for self-administration; the dose of lorcaserin was increased because 3.2 mg/kg did not significantly change rates or methamphetamine intake. After stability criteria were once again satisfied when saline was available for self-administration and when methamphetamine was available, one last dose of lorcaserin (17.8 mg/kg) was given daily for 14 days with methamphetamine available for self-administration followed by two days during which saline was given before sessions.

Drugs.

Cocaine HCl was generously provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program (Bethesda, MD) and methamphetamine HCl was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St. Louis, MO). Both drugs were dissolved in physiologic saline and administered i.v. in a volume of 0.1 ml/kg. Lorcaserin HCl (MedChem Express, Princeton, NJ) was used for studies that investigated the effects of cocaine, whereas lorcaserin HCl hemihydrate was generously provided by Arena Pharmaceuticals (San Diego, CA) for studies in which methamphetamine was available for self-administration. To account for the difference in salt forms of lorcaserin, the concentration of lorcaserin HCl hemihydrate was adjusted to be, and doses are reported as, equivalent to lorcaserin HCl. Both forms of lorcaserin were dissolved in physiologic saline and administered i.g. (nasogastric intubation) in a volume of 0.32 ml/kg. When multiple doses of lorcaserin were examined, dosing began with 3.2 mg/kg, which was the effective dose in monkeys self-administering cocaine under a FR-30:TO 180-second schedule of reinforcement (Collins et al., 2016), and the dose was increased or decreased depending on effects obtained with 3.2 mg/kg.

Data Analysis.

In monkeys responding for cocaine under the PR schedule, the effects of lorcaserin on cocaine self-administration are represented by changes in the mean (± 1 S.E.M.) number of infusions and final ratio completed. For each unit dose of cocaine, 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin was given before a single session; those results were averaged across monkeys with that mean (± 1 S.E.M.) plotted in Fig. 1. Two-factor repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Sidak’s tests was used to determine if the number of infusions varied as a function of cocaine dose or lorcaserin treatment. Monkeys received saline before sessions on multiple days with the same unit dose of cocaine available for self-administration; the mean number of infusions and final ratio completed were determined for individual monkeys by averaging data obtained during four sessions: the two sessions immediately before and the two sessions immediately after the day in which lorcaserin was administered. These individual means were then averaged to obtain the mean (± 1 S.E.M.) plotted in Fig. 1. When lorcaserin was given daily in monkeys responding under the PR schedule for cocaine, the number of infusions was averaged across monkeys for each of the three sessions that immediately preceded daily lorcaserin administration, each day of treatment, and the two sessions that immediately followed lorcaserin treatment; means were plotted as a function of the day of treatment and analyzed by one-factor repeated-measures ANOVA with the day of treatment as the factor and post hoc Dunnett’s tests to determine if the effect of lorcaserin varied as a function of treatment day.

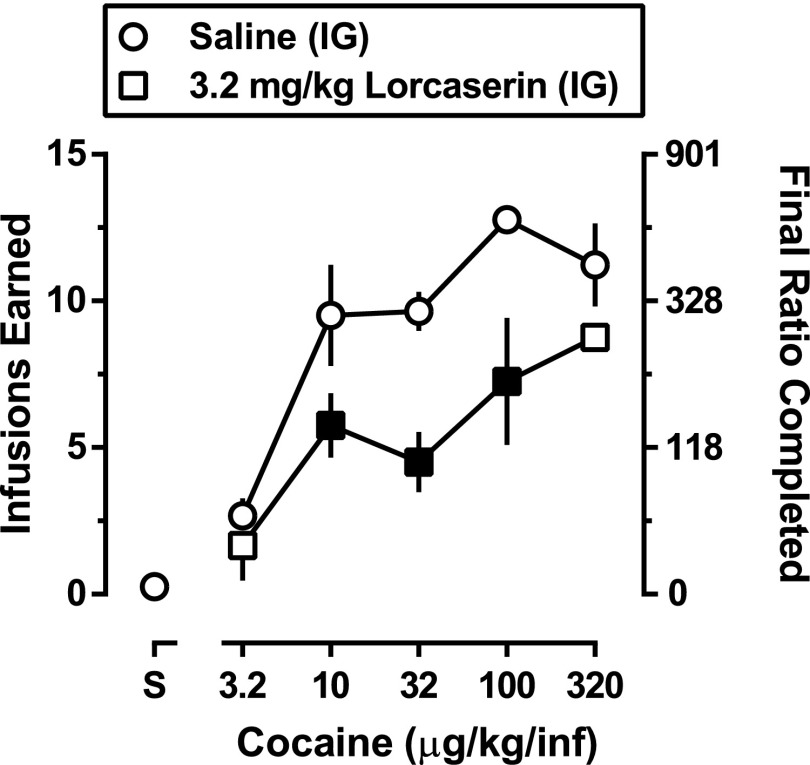

Fig. 1.

Acute effects of lorcaserin on cocaine self-administration in monkeys (n = 4) responding under a PR schedule. Mean (± 1 S.E.M.) number of infusions (left ordinate) and mean (± 1 S.E.M.) final ratio completed (right ordinate) are plotted as a function of unit dose of cocaine. Saline (circles) or 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin (squares) was administered 90 minutes before sessions in which a single unit dose of cocaine was available for self-administration. For each unit dose of cocaine, lorcaserin was given before a single session; however, saline was administered before multiple sessions in which the same unit dose of cocaine was available. Data shown were obtained by first determining the mean number of infusions and final ratio completed for individual monkeys. Data obtained during four sessions were averaged: the two sessions immediately before and the two sessions immediately after the day in which lorcaserin was administered. The individual means were then averaged to obtain the plotted mean (± 1 S.E.M.). One-factor repeated-measures ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett’s tests was used to detect significant effects of lorcaserin treatment (black filled squares, P < 0.05).

For cocaine-induced reinstatement, data from the baseline condition and each of the reinstatement tests represent the total number of reinforced responses (i.e., responses that resulted in cocaine delivery or the presentation of the cocaine-associated stimuli, but not responses made during timeouts), whereas data from the extinction conditions and cocaine reinstatement conducted in the absence of the cocaine-associated stimuli (i.e., sessions in which there were no visual stimuli to differentiate active portions of the session from timeout periods) represent the total number of responses on the previously cocaine-reinforced lever during the extinction session immediately preceding reinstatement tests. To determine whether responding was different across the conditions (e.g., baseline, extinction, and reinstatement with cocaine-associated stimuli alone and in combination with cocaine administered noncontingently) responses per 90-minute session were analyzed with one-factor repeated-measures ANOVA followed by post hoc Dunnett’s tests. This test was also used to determine whether the reinstatement of responding by the cocaine-associated stimuli alone was affected by lorcaserin pretreatment. To determine whether lorcaserin altered the reinstatement of responding by noncontingent infusions of cocaine prior to sessions in which responding was reinforced by presentation of cocaine-associated stimuli, total responding was analyzed with two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA followed by post hoc Sidak’s tests, with cocaine dose and lorcaserin dose as factors. Two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by post hoc Sidak’s tests, was also used to determine if the effectiveness of 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin to reduce the reinstatement of responding by noncontingent cocaine infusions and cocaine-associated stimuli varied when administered either acutely (i.e., only 90 minutes before reinstatement tests) or repeatedly for 5 days prior to reinstatement tests.

In monkeys responding for methamphetamine, response rates were plotted as a function of unit dose of methamphetamine for individual subjects. To summarize the effects of repeated lorcaserin treatment on methamphetamine self-administration, two values were calculated from methamphetamine dose-effect curves. First, response rates obtained during the third cycle (i.e., peak of the methamphetamine dose-effect curve in monkeys receiving saline 90 minutes before sessions) were expressed as a percentage of control rates, which were determined by averaging rates obtained during the third cycle for three consecutive sessions that immediately proceeded the 14-day period of lorcaserin administration. Second, methamphetamine intake for each session was calculated by multiplying the number of infusions delivered in each cycle by the unit dose available during that cycle and adding the intake across cycles. Rates and intake were then averaged across monkeys (± 1 S.E.M.), plotted as a function of session, and analyzed using two-factor-repeated measures ANOVA followed by post hoc Dunnett’s tests, with lorcaserin dose and day of treatment as factors.

Results

Cocaine Self-Administration.

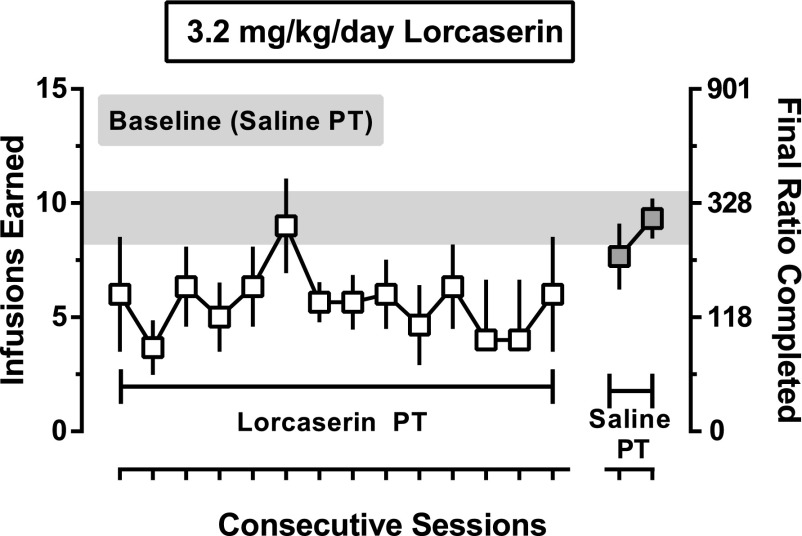

When saline was given i.g. 90 minutes before sessions in which saline was also available for i.v. self-administration, monkeys received, on average, 0.3 ± 0.1 infusions and the final ratio completed was 7.8 ± 7.8. With increasing unit doses of cocaine, there was a dose-dependent increase in number of infusions and final ratio completed; peak responding occurred when 100 μg/kg/infusion was available for self-administration, resulting in delivery of 12.8 ± 0.5 infusions and a final ratio completed of 591.9 ± 48.2 (circles, Fig. 1). When given 90 minutes before sessions, lorcaserin (3.2 mg/kg, i.g.) decreased responding for cocaine and shifted the cocaine dose-effect curve rightward for both number of infusions and final ratio completed (squares, Fig. 1). Two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant main effects of both cocaine dose (F[4,12] = 15.4; P < 0.0001) and lorcaserin dose (F[1,3] = 10.3; P < 0.05), but no cocaine X lorcaserin interaction. Repeated administration of 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin for 14 days did not significantly decrease the mean number of infusions of 32 μg/kg/infusion cocaine that was self-administered at the group level (Fig. 2); however, reductions in responding were observed in two of the three monkeys and those decreases were sustained throughout the period of treatment with lorcaserin (data not shown). When saline replaced lorcaserin 90 minutes before sessions (gray squares, Fig. 2), number of infusions was similar to that obtained before daily lorcaserin administration (gray horizontal bar, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effects of repeated lorcaserin administration on cocaine self-administration in monkeys (n = 3) responding under a PR schedule. The mean (± 1 S.E.M.) number of infusions of 32 μg/kg cocaine (left ordinate) and final ratio completed (right ordinate) are plotted as a function of consecutive sessions. The gray bar represents the mean (± 1 S.E.M.) number of infusions earned (and final ratio) during the three sessions that immediately preceded treatment with 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin (open symbols). Filled symbols represent the mean (± 1 S.E.M.) number of infusions earned (and final ratio) during the two sessions that immediately followed the cessation of lorcaserin treatment.

Cocaine-Primed Reinstatement.

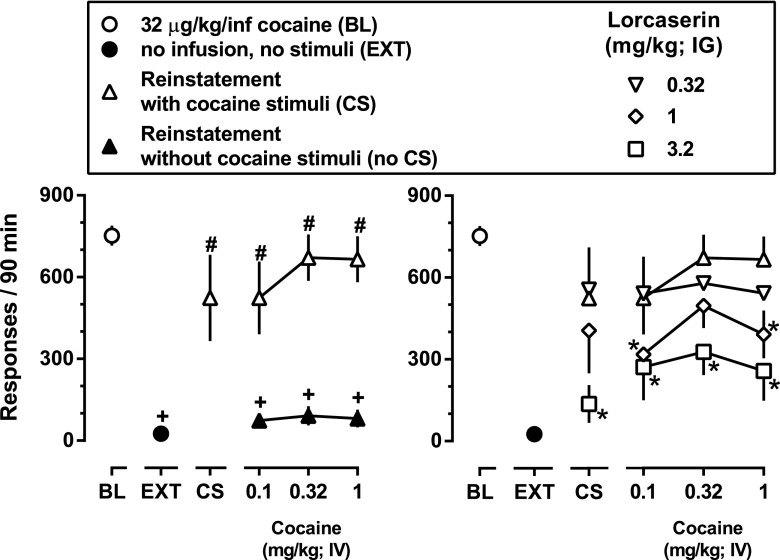

Because there was no difference in the amount of responding across determinations of baseline or extinction, these values were collapsed for individual monkeys, and average responding was used for statistical analyses. Removal of cocaine infusions and their associated stimuli (i.e., extinction) significantly reduced responding (black filled circles above EXT, Fig. 3), with extinction criteria generally met within 3–5 sessions. When a single, noncontingent dose of cocaine (0.1–1 mg/kg i.v.) was administered prior to sessions conducted under extinction conditions (black filled triangles, Fig. 3), responding was significantly lower than that obtained during baseline cocaine self-administration sessions (open circle, Fig. 3) and was not significantly different from responding when infusions of saline preceded the sessions (i.e., extinction conditions; black filled circles, Fig. 3). Reintroduction of the cocaine-associated stimuli reinstated responding (open triangle above CS, Fig. 3). When a single dose of cocaine (0.1–1 mg/kg i.v.) was administered noncontingently at the beginning of the session and cocaine-associated stimuli were presented contingent upon responding throughout the session, there was a significant and robust reinstatement of responding (F[5,15] = 8.0; P < 0.0001) with all three doses of cocaine significantly increasing responding to levels comparable to those observed during baseline conditions in which responding was reinforced by the delivery of 32 μg/kg/infusion cocaine and the associated stimuli (open triangles, Fig. 3). Lorcaserin dose-dependently decreased responding during reinstatement tests with the cocaine-associated stimuli alone (points above CS, Fig. 3) with significant decreases observed at a dose of 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin (F[3,9] = 6.0; P < 0.05). A similar effect was also observed when lorcaserin was administered prior to reinstatement tests with noncontingent injections of cocaine and response-contingent presentations of the cocaine-associated stimuli with significant decreases observed at both 1 and 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin (diamonds and squares, respectively, Fig. 3). The effectiveness of 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin to inhibit the reinstatement of responding by noncontingent administration of cocaine and response-contingent presentations of the cocaine-associated stimuli was not altered when lorcaserin was administered prior to the four extinction sessions that preceded tests of lorcaserin with cocaine and cocaine-associated stimuli (i.e., on day 5 of treatment; Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Effects of lorcaserin on the reinstatement of extinguished responding for cocaine. Left panel depicts the mean (± 1 S.E.M.) number of responses during baseline cocaine self-administration sessions (BL; open circles), the number of responses emitted during the final extinction session (EXT; filled circles) as well as responding emitted during sessions that were preceded by a noncontingent infusion of cocaine (0.1–1 mg/kg cocaine, i.v.) and responding that either resulted in the presentation of the cocaine-associated stimuli (open triangles) or did not (filled triangles). Points above CS represent responding that occurred during sessions that were preceded by saline and responding that resulted in the presentation of the cocaine-associated stimuli (upright triangles). Inverted triangles (0.32 mg/kg lorcaserin), diamonds (1 mg/kg lorcaserin), and squares (3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin) in the right panel depict responding during reinstatement tests that were preceded by i.g. lorcaserin (90 minutes before the start of the session). One-factor (left panel) or two-factor (right panel) repeated-measures ANOVA was used to detect significant differences in responding across conditions: + (P < 0.05) denotes conditions in which responding was significantly lower than that maintained by 32 μg/kg/infusion cocaine (BL); # (P < 0.05) denotes conditions in which responding was significantly greater than during extinction conditions (EXT); and * (P < 0.05) denotes conditions in which lorcaserin significantly decreased the reinstatement of responding by cocaine-associated stimuli alone or by noncontingent cocaine along with the cocaine-associated stimuli (right panel).

Fig. 4.

Effects of lorcaserin on the reinstatement of extinguished responding for cocaine following repeated lorcaserin administration. Triangles and open squares are replotted from Fig. 3 and represent responding that occurred during reinstatement tests with noncontingent cocaine infusions (0.1–1 mg/kg cocaine, i.v.) and the cocaine-associated stimuli that were preceded by acute administration of either saline (triangles) or 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin (open squares). Gray filled squares represent responding that occurred during identical reinstatement tests, but in which 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin was administered once daily for 5 days (i.e., prior to each of the four extinction sessions as well as the reinstatement tests). Two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA was used to detect significant differences in responding across conditions: * (P < 0.05) denotes conditions in which lorcaserin significantly decreased the reinstatement of responding by noncontingent cocaine infusions and cocaine-associated stimuli.

Methamphetamine Self-Administration.

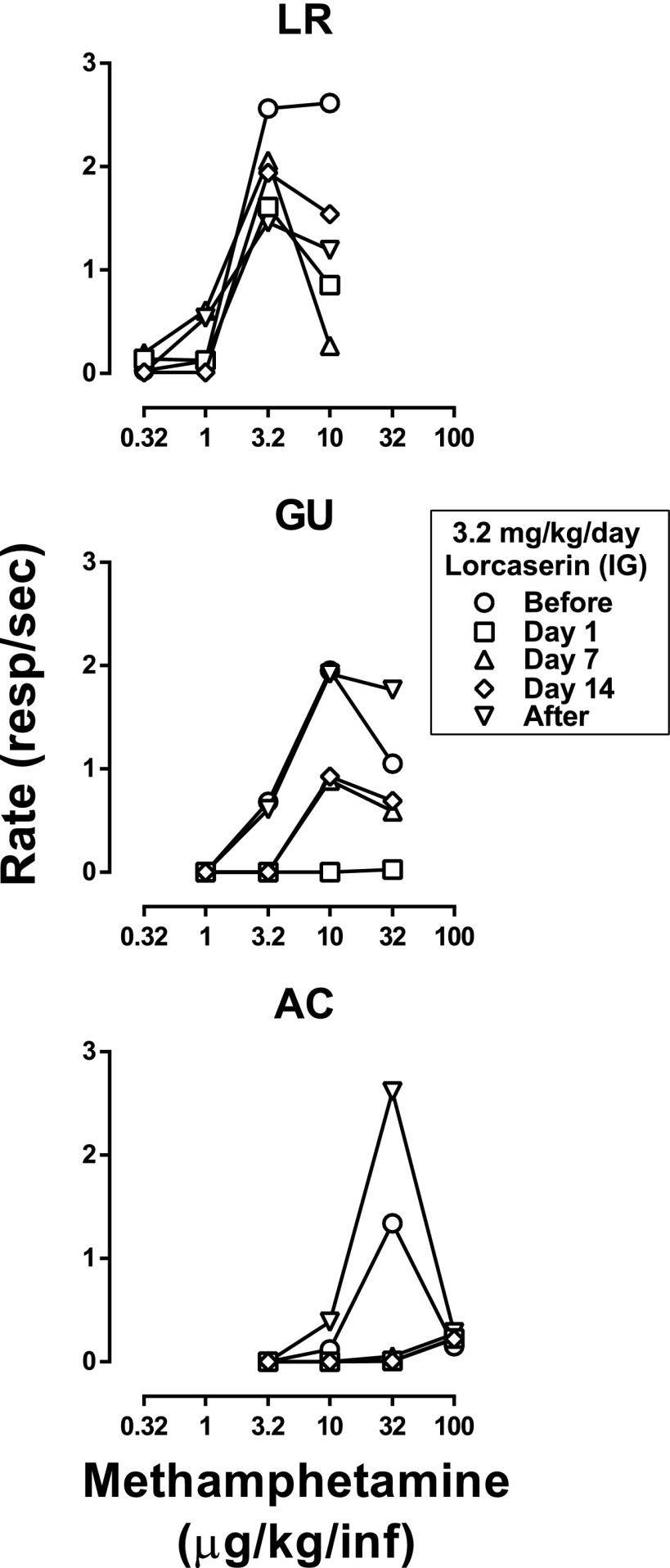

Dose-effect curves for methamphetamine were determined within a single session by increasing the unit dose available for self-administration across the four cycles. Although the dose range varied across monkeys, the smallest dose available maintained little or no responding with the third dose resulting in the largest number of infusions and the highest response rates (circles, Fig. 5). When given acutely 90 minutes before sessions, 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin decreased self-administration in two of the three monkeys (GU and AC), shifting the dose-effect curves rightward and downward, whereas only a modest downward shift was observed in the third monkey (squares, Fig. 5). Daily administration of lorcaserin resulted in a gradual increase in responding for methamphetamine in monkey GU; however, on day 14 of treatment (diamonds, middle panel, Fig. 5) the methamphetamine dose-effect curve remained decreased compared with the one obtained before lorcaserin treatment. Responding remained decreased in one monkey (AC) across 14 days of lorcaserin administration (bottom panel, Fig. 5). When saline replaced lorcaserin 90 minutes before sessions, the decrease in responding for methamphetamine was no longer evident in monkeys GU and AC (inverted triangles, Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effects of 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin (i.g.) on methamphetamine self-administration in three monkeys responding under a FR schedule. Mean (± 1 SEM) response rates are plotted as a function of unit dose of methamphetamine. Each row represents results obtained in an individual monkey. Methamphetamine dose-effect curves were obtained in single sessions by increasing the unit dose across cycles. These sessions were preceded by i.g. administration of saline (i.e., baseline methamphetamine self-administration sessions; circles) or 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin; although lorcaserin was administered daily for 14 consecutive days, methamphetamine dose-effect curves are shown from only a few selected days of treatment (day 1, squares; day 7, upright triangles; day 14, diamonds). In addition, the methamphetamine dose-effect curve generated after treatment was suspended is also shown (inverted triangles; data obtained 25.5 hours after the last dose of lorcaserin).

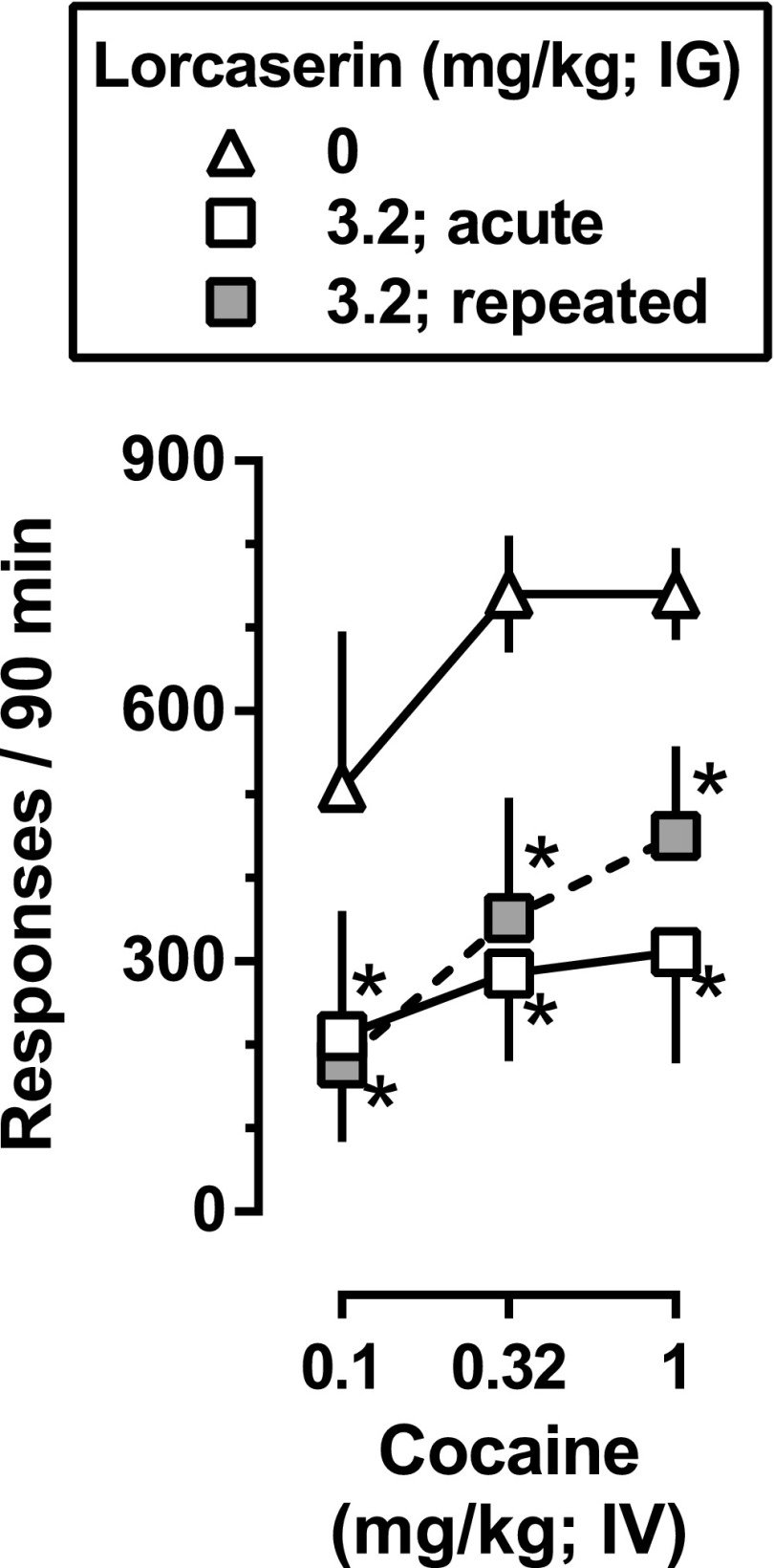

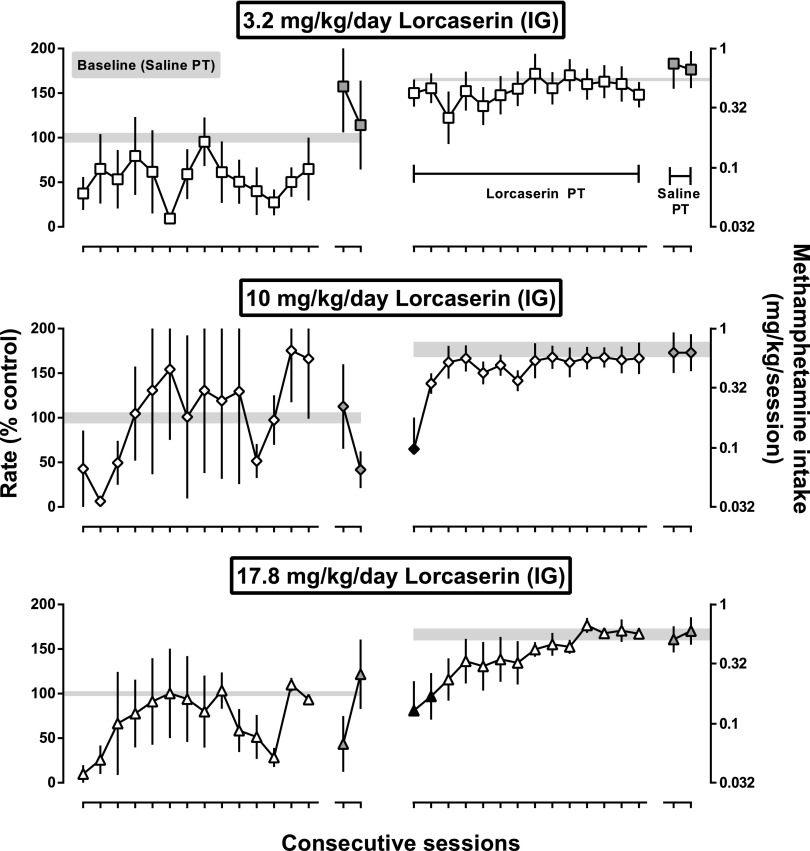

In addition to 3.2 mg/kg, two other doses of lorcaserin (10 and 17.8 mg/kg) were administered for 14 consecutive days with methamphetamine dose-effect curves determined during each daily session. When expressed as a percentage of control, mean response rates obtained during the third cycle were initially decreased for each treatment dose; while response rates remained generally lower than control rates during 14 days of treatment with 3.2 mg/kg, rates recovered quickly with the two larger doses (left panels, Fig. 6). There was a trend toward a significant main effect of treatment day (F[14,28] = 2.0, P = 0.06), no significant main effect of lorcaserin dose, and no interaction between the two factors. Intake across the entire methamphetamine self-administration session was also calculated. Despite the decrease in responding during the third cycle produced by 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin, average methamphetamine intake was not significantly changed by 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin given acutely or repeatedly, which reflects the rightward shift in the methamphetamine dose-effect curve and indicates that the effects of lorcaserin were surmounted when larger unit doses of methamphetamine were available for infusion (upper-right panel, Fig. 6). Larger doses of lorcaserin decreased intake (middle and bottom-right panels, Fig. 6). Overall, there was a significant main effect of treatment day (F[18,36] = 1.9, P < 0.05) and no main effect of lorcaserin dose or interaction between factors. Methamphetamine intake was initially decreased by the two larger doses of lorcaserin (middle and bottom-right panels, Fig. 6); however, this effect was not sustained during daily lorcaserin treatment. By the second day of treatment with 10 mg/kg lorcaserin and the third day of treatment with 17.8 mg/kg, intake was not significantly different from that obtained before lorcaserin treatment. When treatment was suspended, responding for methamphetamine was similar to that obtained before lorcaserin administration (gray filled symbols, Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Effects of repeated lorcaserin administration on mean response rates, expressed as a percentage of control rates, during the third cycle of dose-effect curves and on mean intake of methamphetamine throughout the session in three monkeys responding under a FR schedule. Unit doses of methamphetamine increased across the session, and intake for the session was determined by adding intake at each unit dose of methamphetamine for each monkey and then averaging overall session intake across monkeys. Mean rates and intake (± 1 S.E.M.) are plotted as a function of session during and after 14 consecutive sessions in which lorcaserin (3.2–17.8 mg/kg; i.g.) was administered 90 minutes earlier. Gray shaded areas represent the mean (± 1 S.E.M.) obtained during the three baseline sessions that immediately preceded lorcaserin treatment. Two-factor repeated-measures ANOVAs with post hoc Dunnett’s tests were used to detect significant effects; one factor was treatment day and the second factor was lorcaserin dose (black filled symbols, P < 0.05).

Discussion

Mounting preclinical evidence suggests that agonists acting at 5-HT2C receptors could be beneficial in the treatment of substance abuse disorders. Lorcaserin is a 5-HT2C receptor agonist that is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of obesity (Belviq®) and is currently being considered as a treatment for stimulant abuse. It has a substantial advantage over other pharmacotherapies under development in that it is already approved for use in humans. Initial studies in monkeys showed that lorcaserin attenuated the reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine, thereby supporting its potential use to treat cocaine abuse (Collins et al., 2016). The current studies extended that work by demonstrating that lorcaserin attenuated both ongoing cocaine self-administration in monkeys responding under a PR schedule and the reinstatement of extinguished responding for cocaine. Moreover, when lorcaserin was administered repeatedly, its effects on cocaine self-administration were sustained in individual monkeys across 14 days (current study, Collins et al., 2016), suggesting that tolerance would not develop to lorcaserin when used daily for the treatment of cocaine abuse. Lorcaserin also decreased responding for methamphetamine, an effect that was sustained under some but not all treatment conditions. Thus, results of previous and current studies continue to support the development of lorcaserin for the treatment of cocaine and possibly methamphetamine abuse.

The current studies extended previous results (Collins et al., 2016) by testing the generality of these effects of lorcaserin in nonhuman primates. For example, although lorcaserin reliably decreased cocaine (32 μg/kg/infusion) self-administration across 14 days of treatment, that effect was not surmounted when larger doses of cocaine were available for self-administration under a FR schedule. The current study examined the interaction between lorcaserin and cocaine using a PR schedule, which extends the findings by determining whether lorcaserin reduces the reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine. Under baseline conditions, responding for cocaine increased dose dependently with monkeys emitting approximately 600 responses to receive the final infusion of 100 μg/kg of cocaine. Lorcaserin attenuated the reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine, reducing the final ratio completed to a maximum of 255 responses with a unit dose of 320 μg/kg cocaine. Importantly, this dose of lorcaserin (3.2 mg/kg) shifted the cocaine dose-effect curve rightward rather than downward; that larger doses of cocaine could surmount the effects of lorcaserin indicates that behavior is not entirely suppressed by 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin, which is consistent with results from the earlier study in which 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin did not alter activity and produced a modest, albeit significant, decrease in response rates in monkeys responding for food. Together, the significant reduction in cocaine self-administration observed in monkeys responding under a FR schedule (Collins et al., 2016) and under a PR schedule (current study) was not due to an overall suppression of behavior by lorcaserin, which is important for any drug being considered as a treatment of cocaine abuse. In addition, the reduction in the reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine was not markedly changed with repeated lorcaserin administration in individual monkeys, suggesting that tolerance does not develop to this effect and further supporting the use of lorcaserin.

In addition to reducing ongoing drug use, the high rate of relapse to drug use is one of the biggest challenges in drug abuse treatment. Relapse can be modeled in the laboratory using reinstatement procedures that rely on the ability of drug administered noncontingently and/or drug-associated stimuli to increase extinguished responding that was previous maintained by the drug. In the current study, extinguished responding was increased by presentation of stimuli that were previously associated with cocaine either alone or with noncontingent administration of cocaine; noncontingent administration of cocaine in the absence of the stimuli failed to reinstate responding. Lorcaserin dose-dependently decreased reinstatement of responding, particularly when both the stimuli and noncontingent cocaine were given together. These results suggest that lorcaserin would reduce the likelihood of relapse to cocaine use.

The clinical use of lorcaserin will depend not only on its effectiveness in reducing cocaine abuse but also on other factors, such as safety. For example, pharmacokinetic interactions between lorcaserin and cocaine could impact the effectiveness of lorcaserin or result in dangerous blood levels of cocaine; however, plasma concentrations of lorcaserin and cocaine were not changed when the two were administered together (Collins et al., 2016). Also, yawning, which is mediated by agonist actions at 5-HT2C receptors (Pomerantz et al., 1993; Collins and Eguibar, 2010), occurred after administration of 3.2 mg/kg with a time course that closely followed changes in plasma drug concentrations obtained after administration of the same dose (Collins et al., 2016). In the current study, yawning was noted in one monkey receiving 10 mg/kg lorcaserin and in all three monkeys receiving 17.8 mg/kg. Together, these results suggest that 5-HT2C receptors contribute to the behavioral effects of 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin and that concurrent administration of lorcaserin and cocaine do not change the pharmacokinetics of either drug (current study; Collins et al., 2016). Doses of lorcaserin larger than 3.2 mg/kg are needed to substantially decrease spontaneous activity and food-maintained responding (Collins et al., 2016); this behavioral selectivity of lorcaserin indicates that adverse effects might be avoided if lorcaserin is used to treat cocaine abuse. However, the current data also suggest that the effects of lorcaserin can be surmounted by larger unit doses of cocaine, which could reduce the clinical effectiveness of lorcaserin when larger quantities of cocaine are available.

Although these studies support the continued investigation of the clinical use of lorcaserin, it is not clear that lorcaserin would be equally useful in treating abuse of other stimulant drugs. When given acutely, lorcaserin decreased response rates in two of the three monkeys self-administering methamphetamine. Because the effects of lorcaserin on cocaine self-administration were surmounted by larger unit doses (i.e., cocaine dose-effect curve was shifted rightward), methamphetamine intake was also considered to determine whether decreased rates were due to rightward or downward shifts in the methamphetamine dose-effect curve. Rightward shifts would be evident by decreased response rates during the third cycle (left panels, Fig. 6) that were not accompanied by changes in intake (right panels, Fig. 6), whereas downward shifts would be evident by decreases in both measures and would indicate a general suppression of behavior. A dose of 3.2 mg/kg lorcaserin resulted in rightward and downward shifts in two of the three monkeys self-administering methamphetamine that were at least partially sustained throughout the 14-day treatment period. Larger doses of lorcaserin initially shifted the methamphetamine dose-effect curve downward; however, these effects were not sustained across the 14-day treatment period. While larger treatment doses of lorcaserin might be expected to be more effective in decreasing methamphetamine self-administration, such doses might not be practical in humans because other effects of lorcaserin would likely emerge, such as a decrease in overall activity. Another potentially important concern with the use of lorcaserin in methamphetamine abusers is the possible development of tolerance; in the current study, tolerance developed to effects of the two larger doses of lorcaserin, and with repeated administration, attenuation of methamphetamine intake was no longer evident. Thus, lorcaserin might not be useful in reducing abuse of methamphetamine at least at doses of lorcaserin that do not produce adverse effects. Although it is possible that the differential effects of lorcaserin on responding maintained by cocaine and methamphetamine could be related to differences in the mechanisms of action for cocaine (inhibition of monoamine uptake) and methamphetamine (inhibition of monoamine uptake and stimulation of monoamine release), further study would be required to confirm this possibility.

In summary, these results support the view that lorcaserin might be beneficial in treating cocaine abuse because it decreases ongoing self-administration in the FR schedule (Collins et al., 2016) and PR schedule (current study) and reinstatement of extinguished responding at a dose that is smaller than the doses producing other, potentially adverse, effects. To the extent that reinstatement procedures model relapse to drug use, these studies suggest that lorcaserin would be effective in reducing cocaine use before and after drug use is discontinued. Because it is impossible to predict when relapse will occur, it is important that the effects of lorcaserin are sustained over repeated daily dosing. Results of the current studies suggest that tolerance does not develop to a dose of lorcaserin (3.2 mg/kg in monkeys) that selectively decreases cocaine self-administration without decreasing all behavior (current study; Collins et al., 2016) and that long-term treatment is possible without decrement in its effectiveness. Consequently, these studies support the continued investigation of lorcaserin in humans for the treatment of stimulant abuse.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions and leadership of Dr. Roger D. Porsolt in the design and planning of these studies and for the authorship of the original grant application. The authors thank Eli Desarno, Marlisa Jacobs, Nicole Garcia, Steven Garza, and Taylor Martinez for technical contributions toward the completion of these studies.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine or serotonin

- FR

fixed ratio

- i.g.

intragastric

- PR

progressive ratio

- TO

timeout

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Gerak, Collins, France.

Conducted experiments: Gerak, Collins.

Performed data analysis: Gerak, Collins.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Gerak, Collins, France.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grants U01 DA034992 and K05 DA017918] and by the Welch Foundation [Grant AQ-0039].

The authors have no conflict of interest. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

References

- Burbassi S, Cervo L. (2008) Stimulation of serotonin2C receptors influences cocaine-seeking behavior in response to drug-associated stimuli in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 196:15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister JJ, Lungren EM, Kirschner KF, Neisewander JL. (2004) Differential roles of 5-HT receptor subtypes in cue and cocaine reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 29:660–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Eguibar JR. (2010) Neurophamacology of yawning. Front Neurol Neurosci 28:90–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Gerak LR, Javors MA, France CP. (2016) Lorcaserin reduces the discriminative stimulus and reinforcing effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 356:85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KA, Fox RG, Anastasio NC, Bubar MJ, Stutz SJ, Moeller FG, Gilbertson SR, Rosenzweig-Lipson S. (2011) Selective serotonin 5-HT2C receptor activation suppresses the reinforcing efficacy of cocaine and sucrose but differentially affects the incentive-salience value of cocaine- vs. sucrose-associated cues. Neuropharmacology 61:513–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grottick AJ, Fletcher PJ, Higgins GA. (2000) Studies to investigate the role of 5-HT2C receptors on cocaine- and food-maintained behavior. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 295:1183–1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey-Lewis C, Li Z, Higgins GA, Fletcher PJ. (2016) The 5-HT2C receptor agonist lorcaserin reduces cocaine self-administration, reinstatement of cocaine-seeking and cocaine induced locomotor activity. Neuropharmacology 101:237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Silenieks LB, Lau W, de Lannoy IAM, Lee DKH, Izhakova J, Coen K, Le AD, Fletcher PJ. (2013) Evaluation of chemically diverse 5-HT2C receptor agonists on behaviours motivated by food and nicotine and on side effect profiles. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 226:475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Silenieks LB, Rossmann A, Rizos Z, Noble K, Soko AD, Fletcher PJ. (2012) The 5-HT2C receptor agonist lorcaserin reduces nicotine self-administration, discrimination, and reinstatement: relationship to feeding behavior and impulse control. Neuropsychopharmacology 37:1177–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Cunningham KA. (2015) Serotonin 5-HT2 receptor interactions with dopamine function: implications for therapeutics in cocaine use disorder. Pharmacol Rev 67:176–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Johnson JE, Slade S, Wells C, Cauley M, Petro A, Rose JE. (2011) Lorcaserin, a 5-HT2C agonist, decreases nicotine self-administration in female rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 338:890–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manvich DF, Kimmel HL, Howell LL. (2012) Effects of serotonin 2C receptor agonists on the behavioral and neurochemical effects of cocaine in squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 341:424–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (2011) Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals: eight edition Washington DC; National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz SM, Hepner BC, Wertz JM. (1993) 5-HT1A and 5-HT1C/1D receptor agonists produce reciprocal effects on male sexual behavior of rhesus monkeys. Eur J Pharmacol 243:227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson NR, Roberts DC. (1996) Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J Neurosci Methods 66:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ. (1987) Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science 237:1219–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüedi-Bettschen D, Spealman RD, Platt DM. (2015) Attenuation of cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug seeking in squirrel monkeys by direct and indirect activation of 5-HT2C receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232:2959–2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafine KM, Rice KC, France CP. (2015) Directly observable behavioral effects of lorcaserin in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 355:381–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen WJ, Grottick AJ, Menzaghi F, Reyes-Saldana H, Espitia S, Yuskin D, Whelan K, Martin M, Morgan M, Chen W, et al. (2008) Lorcaserin, a novel selective human 5-hydroxytryptamine2C agonist: in vitro and in vivo pharmacological characterization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 325:577–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojnicki FH, Bacher JD, Glowa JR. (1994) Use of subcutaneous vascular access ports in rhesus monkeys. Lab Anim Sci 44:491–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]